Validating the Biological Relevance of Natural Product-Inspired Compounds: Strategies for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing the biological relevance of natural product (NP)-inspired compounds.

Validating the Biological Relevance of Natural Product-Inspired Compounds: Strategies for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing the biological relevance of natural product (NP)-inspired compounds. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation techniques, it explores why NPs are privileged starting points for drug discovery, details modern design and synthesis methodologies like DOS and BIOS, addresses common optimization challenges such as ADMET properties and chemical accessibility, and finally, presents rigorous experimental and computational frameworks for target identification and mechanistic validation. The synthesis of these areas offers a strategic roadmap for efficiently transforming NP-inspired chemical designs into validated probes and drug candidates.

Why Nature's Blueprint is a Premier Source for Bioactive Compounds

The Unique Chemical Space of Natural Products

The concept of "chemical space"—a representation of chemical compounds in a multi-dimensional descriptor space—is fundamental to modern drug discovery. Within this universe of possible molecules, natural products (NPs) occupy a distinct and privileged region, shaped by billions of years of evolutionary pressure to interact with biological systems [1]. These compounds, synthesized by living organisms like plants, bacteria, and fungi, have historically been a cornerstone of pharmacotherapy, especially for cancer and infectious diseases [2]. In contrast, synthetic compounds (SCs) designed in laboratories often occupy a different, and sometimes narrower, region of chemical space, influenced by the constraints of synthetic feasibility and drug-like rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five [1].

The biological relevance of NPs is not accidental; it is the result of natural selection. NPs have evolved to perform specific ecological functions, which often involve interactions with protein targets, making them pre-validated for biological activity [3]. This inherent bio-relevance translates into tangible advantages in the drug development pipeline, as evidenced by the higher clinical success rates of NP-inspired compounds [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the structural and performance characteristics of NPs versus SCs, offering a validated framework for leveraging NPs in research.

Comparative Analysis: Structural and Performance Data

Structural and Physicochemical Properties

A time-dependent chemoinformatic analysis of over 186,000 NPs and 186,000 SCs reveals significant and consistent differences in their structural characteristics [1]. The following table summarizes key comparative data.

Table 1: Comparative Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds

| Property | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Generally larger; increasing over time (MW, volume, surface area) [1] | Smaller; varies within a limited range constrained by synthetic and drug-like rules [1] | NPs access a broader range of molecular targets, including challenging protein-protein interactions. |

| Ring Systems | More rings, predominantly non-aromatic; larger fused rings (e.g., bridged, spiral) [1] | Fewer rings but more ring assemblies; high prevalence of aromatic rings (e.g., benzene) [1] | NP scaffolds offer greater 3D structural complexity and saturation, beneficial for selectivity and ADME properties. |

| Structural Diversity & Complexity | Higher structural diversity, complexity, and uniqueness [1] | Broader synthetic pathways but lower structural diversity and complexity compared to NPs [1] | NP libraries are a superior source of novel, non-planar scaffolds for library design and hit generation. |

| Oxygen & Nitrogen Content | Higher number of oxygen atoms [1] | Higher number of nitrogen atoms [1] | Reflects different biochemical origins and influences compound polarity, hydrogen bonding, and target engagement. |

| Glycosylation | Glycosylation ratios and number of sugar rings increase over time [1] | Less common | Glycosylation can profoundly impact solubility, target recognition, and pharmacokinetics. |

Performance in the Drug Development Pipeline

The unique structural properties of NPs directly influence their performance and success rates in the arduous journey from discovery to approved drug. Clinical trial data and approval statistics demonstrate a clear trend.

Table 2: Performance and Success Rates of Natural Products vs. Synthetic Compounds in Drug Development

| Development Stage | Natural Products & NP-Like Compounds | Synthetic Compounds | Data Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patent Applications (proxy for early discovery) | ~23% (NPs & Hybrids combined) [3] | ~77% [3] | SCs dominate initial discovery, reflecting historical industry focus and patentability challenges for pure NPs. |

| Clinical Trial Phase I | ~35% (NPs & Hybrids combined) [3] | ~65% [3] | A shift begins, with NP-inspired compounds already showing a higher propensity to enter human trials. |

| Clinical Trial Phase III | ~45% (NPs & Hybrids combined) [3] | ~55% [3] | A significant increase in the proportion of NP-inspired compounds, indicating a much higher "survival rate" through clinical phases. |

| FDA-Approved Drugs (1981-2019) | ~68% (directly, derivatives, or NP-pharmacophore inspired) [3] | ~25% (purely synthetic) [3] | NPs and their mimics constitute a majority of approved small-molecule drugs, underscoring their ultimate clinical value. |

| In Vitro/In Silico Toxicity | Tend to be less toxic [3] | Higher toxicity risk [3] | Reduced toxicity is a key factor in the higher clinical success rate of NPs, mitigating a major cause of drug candidate attrition. |

Specific NP classes are enriched in approved drugs compared to early clinical phases. Terpenoids show a ~20% relative increase, while fatty acids and alkaloids increase by ~7% and ~6%, respectively. Conversely, carbohydrates and amino acids see a decrease in abundance by the approval stage [3].

Experimental Protocols for Chemoinformatic Analysis

To objectively compare the chemical space of NPs and SCs, researchers employ a rigorous chemoinformatic workflow. The following protocol, based on a published time-dependent analysis, provides a template for such investigations [1].

Protocol 1: Time-Dependent Chemical Space Comparison

Objective: To characterize and compare the structural evolution and chemical space of NPs and SCs over time.

Methodology:

Data Curation:

- Source: Obtain NP structures from the Dictionary of Natural Products and SCs from a collection of synthetic chemistry databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) [1] [3].

- Classification: Define criteria for "NP-likeness," which may include structural similarity to known NP scaffolds or the use of "pseudo-NP" design strategies that combine NP fragments [1].

- Temporal Sorting: Sort molecules in chronological order using a reliable timestamp, such as the CAS Registry Number, which reflects the date a compound was registered [1].

Descriptor Calculation:

- Compute a set of ~39 relevant molecular descriptors for all compounds. Essential descriptors include [1]:

- Size & Bulk: Molecular Weight, Molecular Volume, Molecular Surface Area, Number of Heavy Atoms, Number of Bonds.

- Ring Systems: Number of Rings, Aromatic Rings, Non-Aromatic Rings, Ring Assemblies.

- Complexity & Lipophilicity: Number of Stereocenters, Calculated LogP.

- Compute a set of ~39 relevant molecular descriptors for all compounds. Essential descriptors include [1]:

Structural Deconstruction:

- Generate and analyze molecular fragments to understand scaffold and side-chain diversity.

Chemical Space Mapping & Statistical Analysis:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to project the high-dimensional descriptor data into 2D or 3D space for visualization [1].

- Advanced Visualization: Employ methods like Tree MAP (TMAP) to create visual similarity maps that illustrate the diversity and clustering of NPs versus SCs [1].

- Statistical Comparison: Apply statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests) to compare the distributions of molecular properties between NP and SC groups across different time periods.

Visual Workflow:

Protocol 2: Assessing Biological Relevance and Clinical Success

Objective: To evaluate the biological relevance and clinical progression of NPs versus SCs.

Methodology:

Data Sourcing:

- Clinical Trial Data: Compile data on compounds entering Phase I, II, and III clinical trials from public repositories (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov).

- Approved Drug Data: Use sources like the FDA Orange Book and published compilations [3].

Classification:

- Categorize each compound as: NP (unaltered natural product), Hybrid (semi-synthetic derivative or NP-inspired), or Synthetic (purely synthetic origin with no NP inspiration) [3].

Progression Analysis:

- Track the proportion of NPs, Hybrids, and SCs across Phase I, II, and III.

- Calculate the "attrition rate" or "success rate" for each category from one phase to the next.

In Silico Toxicity Prediction:

- Use computational models to predict toxicity endpoints (e.g., hepatotoxicity, mutagenicity) for NP and SC datasets to correlate structural class with safety profiles [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successfully navigating the unique chemical space of natural products requires a specific set of tools and reagents. The following table details key solutions for NP-based drug discovery.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Application in NP Research |

|---|---|

| Natural Product Extract Libraries | Complex mixtures of compounds sourced from microbial fermentation, plants, or marine organisms. Serve as the primary material for bioactivity screening and novel compound discovery [2]. |

| Bioassay-Ready HTS Screening Libraries | Pre-fractionated microbial or plant extracts, or isolated NP libraries, designed for use in High-Throughput Screening (HTS) campaigns to identify hits with desired biological activity [2]. |

| Analytical-Grade Solvents & Separation Kits | Essential for the extraction, pre-fractionation, and purification of NPs from complex biological matrices using techniques like Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) and Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) [2]. |

| Dereplication Databases (e.g., DNP, COCONUT) | Computational databases used to quickly identify known compounds in bioactive extracts, preventing redundant discovery and focusing efforts on novel chemistry [2]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Nutrients (e.g., ¹³C-Glucose) | Used in microbial cultures for isotope labeling. Allows for precise metabolic flux studies and facilitates structural elucidation of novel NPs via techniques like high-resolution mass spectrometry [2]. |

| LC-HRMS Systems | Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry systems are the cornerstone of modern NP research, enabling the separation, detection, and accurate mass determination of compounds in complex mixtures [2]. |

| NMR Solvents & Profiling Kits | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance solvents and standardized kits are used for structural elucidation and rapid metabolic profiling of NP extracts, providing complementary data to HRMS [2]. |

| Genome Mining Software | Bioinformatics tools used to analyze the genomes of organisms to predict the existence of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) for novel NPs, guiding targeted isolation efforts [2]. |

Pre-Validated Biological Relevance and Privileged Scaffolds

Natural Products (NPs) and their privileged scaffolds represent a cornerstone of modern therapeutics, with approximately one-third of all approved small-molecule drugs since 1981 falling into the category of NPs, their derivatives, or inspired compounds [4]. This remarkable success stems from an evolutionary advantage: these molecules have co-evolved with their biosynthetic proteins, exploring biologically relevant chemical space and encoding inherent biological relevance through their ability to bind biomacromolecules and cross cell membranes [4]. The term "pre-validated biological relevance" captures this intrinsic bioactivity, refined through millions of years of evolutionary selection to interact with biological systems [5]. Similarly, "privileged scaffolds" refer to molecular frameworks with proven capability to interact with multiple, often unrelated, protein families or biological targets [4] [6].

The landscape of NP-inspired drug discovery has evolved significantly, moving beyond simply isolating and modifying natural products to sophisticated strategies that recombine, diversify, and computationally generate novel scaffolds while preserving this valuable pre-validation. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the major strategic approaches—Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS), Pseudo-Natural Products (PNPs), and Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS)/privileged-substructure-based DOS (pDOS)—focusing on their methodologies for ensuring biological relevance and their application of privileged scaffolds in discovering new therapeutic agents.

Table 1: Core Strategic Approaches to Natural Product-Inspired Discovery

| Strategy | Core Principle | Source of Biological Relevance | Scaffold Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS) | Hierarchical classification of NP scaffolds to guide synthesis [7] [8] | Retention of entire, evolutionarily selected NP scaffolds [4] [6] | Directly from known natural products [4] |

| Pseudo-Natural Products (PNPs) | Recombination of biosynthetically unrelated NP fragments into novel scaffolds [7] [6] [9] | Inherited from biologically pre-validated NP fragments/building blocks [4] [9] | New, unprecedented frameworks not found in nature [4] [7] |

| DOS/pDOS | Creation of high structural diversity, often with NP-like features [4] [7] | Exploration of complex, 3D chemical space; not necessarily derived from a specific NP [4] [7] | Can be synthetic or inspired by privileged substructures [4] |

Strategic Comparison: Mechanisms for Ensuring Bioactivity

Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS)

BIOS operates on the principle of conserving core structural scaffolds of natural products throughout the synthesis and decoration process. This strategy identifies a conserved core scaffold during the lead identification phase and typically maintains it during subsequent compound collection design [8]. The underlying hypothesis is that conserving the scaffold preserves the original bioactivity profile of the parent natural product while allowing for optimization through synthetic modification. This approach provides a direct link to evolutionarily optimized molecular frameworks but may limit exploration of novel chemical space.

Pseudo-Natural Products (PNPs)

The PNP strategy represents a more radical departure from traditional approaches. It involves the design and synthesis of novel molecular scaffolds by combining two or more biosynthetically unrelated natural product fragments in ways not observed in nature [7] [6]. This fusion creates compounds that occupy a unique position in chemical space—they are not found in nature, yet their constituent parts carry biological pre-validation. The indotropane scaffold serves as a prime example, created by fusing indole and tropane alkaloid fragments, which independently possess extensive biological profiles [7]. This approach aims to generate new bioactivities not achievable with classical NP derivatives while overcoming the synthetic challenges often associated with complex natural products [9].

Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) and Privileged-Substructure-Based DOS (pDOS)

DOS focuses on generating high structural diversity with characteristics typical of NPs, such as a high fraction of sp³-hybridized carbons and multiple stereogenic centers, though it is not necessarily based on a specific NP scaffold [4]. The related pDOS strategy builds on privileged scaffolds with proven biological relevance, which may or may not be derived from natural products [4]. A key differentiator for both DOS and pDOS is their emphasis on molecular scaffold diversity as a primary objective, in contrast to the more focused approaches of BIOS and many PNP syntheses [4].

Experimental Comparison & Performance Data

Antibacterial Agent Discovery: A Case Study

The application of these strategies in addressing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) provides compelling comparative data. Researchers applied the PNP hypothesis to design and synthesize a focused collection of indotropane compounds, subsequently evaluating them against methicillin- and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA/VRSA) strains [7].

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes of Indotropane PNPs Against Resistant S. aureus

| Compound ID | Scaffold Type | MRSA MIC (μg/mL) | VRSA MIC (μg/mL) | Mammalian Cell Cytotoxicity (CC50, μg/mL) | Selectivity Index (CC50/MIC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7af | Indotropane PNP | 8 | 16 | >128 | >16 |

| 7ag | Indotropane PNP | 4 | 8 | >128 | >32 |

| 7ah | Indotropane PNP | 2 | 4 | >128 | >64 |

| Vancomycin | Natural Product | - | 16-32 | - | - |

Experimental Protocol: The antibacterial activity was evaluated using a broth microdilution method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) was determined against clinical isolates of MRSA and VRSA. Cytotoxicity (CC50) was assessed against mammalian HEK293T cells using an MTT assay after 24-hour exposure. The selectivity index was calculated as CC50/MIC for MRSA [7].

The most potent compound, 7ah, demonstrated significant potency (MIC 2-4 μg/mL) and a high selectivity index (>64), indicating its potential as a promising antibacterial candidate. This represents one of the first successful applications of the PNP hypothesis to antibacterial discovery, highlighting its capability to generate novel chemotypes with significant bioactivity [7].

Strategic Performance Metrics

When compared across broader performance dimensions, each strategy demonstrates distinct strengths and limitations.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of NP-Inspired Discovery Strategies

| Performance Metric | BIOS | PNP | DOS/pDOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Novelty | Low (known NP scaffolds) | High (unprecedented frameworks) [4] [9] | Variable (can be high) [4] |

| Synthetic Accessibility | Variable (can be challenging) | Designed for improved tractability [7] [6] | High (synthetic feasibility prioritized) [4] |

| Hit Rate in Phenotypic Screens | High (due to retained bioactivity) [4] | High (e.g., indotropanes vs. MRSA) [7] | Variable (broader exploration) [4] |

| Coverage of NP-like Chemical Space | Limited to known NP regions | Expands into adjacent, unexplored space [4] [6] | Broad but less focused on NP-likeness |

| Typical Molecular Complexity | High (similar to NPs) | Moderate to High (NP-inspired) [4] | Variable (often lower than NPs) |

Methodologies and Workflows

Experimental Protocol: Pseudo-Natural Product Synthesis

The synthesis of indotropane PNPs follows a well-established route with the following key steps [7]:

- Scaffold Design: Select biologically pre-validated fragments (indole and tropane alkaloids) known for diverse bioactivities.

- Core Construction: Build the indotropane core through a [3+2] cycloaddition reaction of azomethine ylides derived from dihydro-β-carboline as dipoles with nitrostyrenes as electron-deficient dipolarophiles.

- Stereochemical Control: The final product is obtained as the exo'-diastereomer in racemic form.

- Library Diversification: Introduce structural diversity through varying substituents on the phenyl ring of the tropane fragment to establish structure-activity relationships (SAR).

- Purification and Characterization: Purify compounds by column chromatography or recrystallization, with characterization by ¹H NMR, ¹³C NMR, DEPT, and HRMS.

Computational Protocol: NIMO Generative Model

The NIMO (Natural Product-Inspired Molecular Generative Model) represents a cutting-edge computational approach that leverages the principles of PNPs [8]:

- Motif Extraction: Map molecular graphs into semantic motif sequences using tailor-made extraction methods.

- Model Training: Train conditional transformer models under different task scenarios (NIMO-S for scaffold-based generation, NIMO-M for multi-constraint generation) to recognize syntactic patterns and structure-property relationships.

- Structure Generation: Generate novel compounds either de novo or through structure optimization from a scaffold.

- Property Optimization: Apply multi-objective optimization for desired properties including quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility score (SAS), and target-specific activity.

- Validation: Evaluate generated structures for validity, uniqueness, novelty, and diversity against benchmark datasets.

In benchmark studies, NIMO successfully generated molecules with preferred NP-like features, achieving high scores for fragment coverage (Frag metric) and synthetic accessibility, demonstrating the power of computational approaches to expand NP-inspired chemical space [8].

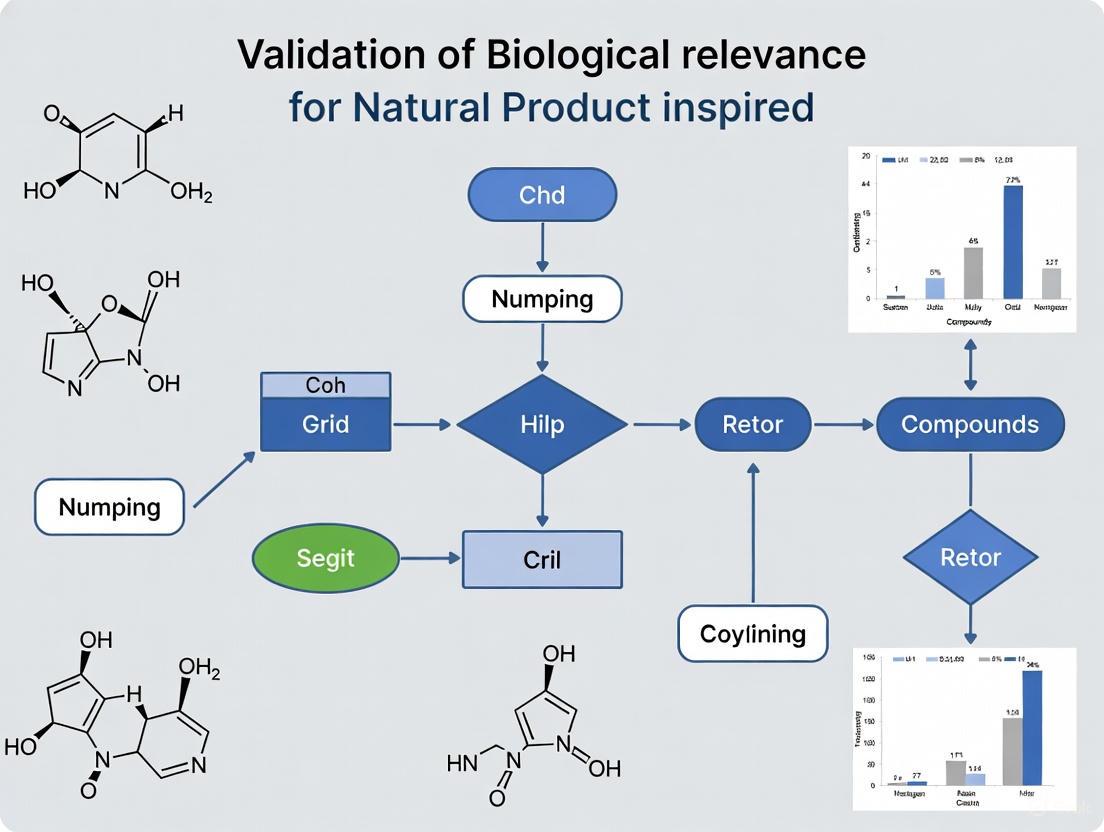

Diagram 1: Pseudo-Natural Product Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for NP-Inspired Compound Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Dihydro-β-carboline | Dipole precursor for cycloaddition | Core construction in indotropane PNP synthesis [7] |

| Nitrostyrene Derivatives | Electron-deficient dipolarophiles | Tropane ring formation in [3+2] cycloadditions [7] |

| Cell Painting Assay (CPA) | High-content phenotypic profiling | Mechanism-of-action elucidation for novel PNPs [9] |

| LC-MS/MS with GNPS | Metabolomic analysis & dereplication | Scaffold diversity analysis in library design [10] |

| Molecular Networking | MS/MS data visualization & scaffold grouping | Rational library reduction & diversity assessment [10] |

The strategic integration of pre-validated biological relevance and privileged scaffolds continues to drive innovation in drug discovery. BIOS offers a conservative approach with high confidence in retained bioactivity, while PNPs creatively expand into novel chemical space with promising success in generating new bioactivities, as demonstrated by the indotropane class's potent antibacterial effects. DOS/pDOS provides maximal diversity but with less direct connection to evolutionarily validated scaffolds. The emerging synergy between synthetic methodology and computational design, exemplified by tools like NIMO, promises to accelerate the exploration of biologically relevant chemical space, offering powerful new approaches to address unmet medical needs through nature-inspired molecular design.

Diagram 2: Continuum of Compound Similarity to Natural Product Frameworks

Natural products (NPs) and their derivatives have historically been a major source of therapeutic agents, accounting for approximately one-third of all FDA-approved drugs over the past two decades [11]. This success stems primarily from their unparalleled mechanistic diversity—their ability to interact with biological systems through novel and evolutionarily refined modes of action. Unlike synthetic compounds (SCs) often designed around limited pharmacophore models, NPs originate from billions of years of evolutionary selection for specific biological interactions, including defense mechanisms, signaling functions, and ecological competition [5]. This evolutionary optimization equips NPs with complex chemical architectures that modulate challenging biological targets, particularly protein-protein interactions and allosteric sites, which often remain intractable to synthetic compounds [2] [5].

The structural evolution of NPs over time reveals they have become larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic, exhibiting increased structural diversity and uniqueness [1]. This expanding chemical space provides a continuously renewing resource for discovering novel biological mechanisms. NPs are characterized by higher molecular complexity, including increased proportions of sp³-hybridated carbon atoms, greater oxygenation, and more stereochemical complexity compared to synthetic libraries [5]. These features underpin their ability to achieve target selectivity and efficacy against multifactorial diseases, making them invaluable for addressing antimicrobial resistance, oncology, and other complex therapeutic areas [2] [12]. This guide systematically compares the performance of NPs against synthetic alternatives, providing experimental frameworks for validating their mechanistic diversity within drug discovery pipelines.

Comparative Analysis: Structural and Mechanistic Foundations

Quantitative Comparison of Key Properties

Table 1: Time-Dependent Structural Comparison of Natural Products vs. Synthetic Compounds

| Property Category | Specific Metric | Natural Products Trend | Synthetic Compounds Trend | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Molecular Weight | Consistent increase over time (larger compounds) [1] | Limited variation, constrained by drug-like rules [1] | NPs access larger, complex binding interfaces; SCs optimized for oral bioavailability |

| Heavy Atom Count | Gradual increase [1] | Stable within defined range [1] | NPs offer more interaction points with biological targets | |

| Structural Complexity | Number of Rings | Gradual increase, mostly non-aromatic [1] | Moderate increase, predominantly aromatic [1] | NPs provide diverse 3D architectures; SCs often planar structures |

| Stereogenic Centers | Higher density of chiral centers [5] | Lower stereochemical complexity [5] | NPs achieve precise target recognition and selectivity | |

| Chemical Composition | Oxygen Atoms | Higher oxygen content [5] [1] | Higher nitrogen and halogen content [5] [1] | NPs favor H-bonding interactions; SCs often rely on aromatic/halogen interactions |

| Glycosylation | Increasing glycosylation ratio over time [1] | Rare | NPs enhanced solubility and target recognition via sugar moieties |

The data reveal fundamental divergences in chemical evolution. NPs have continuously expanded toward greater structural complexity, while SCs remain constrained by synthetic accessibility and traditional drug-like criteria [1]. This structural divergence directly enables NPs' superior mechanistic diversity, as their complex, oxygen-rich structures with multiple stereocenters are evolutionarily optimized for binding to biological macromolecules [5].

Performance Comparison in Drug Discovery

Table 2: Experimental Data on Drug Discovery Performance and Biological Relevance

| Performance Metric | Natural Products | Synthetic Compounds | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Relevance | Higher, evolutionarily optimized [5] [1] | Lower, designed for specific properties [1] | Time-dependent analysis shows consistent bio-relevance for NPs [1] |

| Chemical Space Coverage | More diverse and unique [1] | Broader but less biologically relevant [1] | PCA and TMAP analysis demonstrate NP structural uniqueness [1] |

| FDA Approval Rate | ~34% of all approved drugs (1981-2019) [11] [13] | Majority but with lower success rate per candidate [13] | Clinical trial data and drug approval databases |

| Target Class Diversity | Broad, including challenging PPIs [2] [5] | Narrower, focused on traditional druggable targets [1] | High-throughput screening data across multiple target classes |

| Success in Antibiotics | Majority of new classes [2] | Limited recent success [2] | Historical drug approval data and clinical pipelines |

| Success in Oncology | Significant contributions (e.g., paclitaxel) [5] [14] | Moderate contributions | NCI screening programs and clinical trial results |

The experimental data consistently demonstrates that NPs access broader and more diverse biological mechanisms than SCs. Their evolutionary origin as defense molecules or signaling agents makes them particularly effective against biological vulnerabilities in pathogens and cancer cells [5]. Furthermore, their structural complexity enables them to address challenging target classes that have proven resistant to synthetic approaches, particularly in infectious disease and oncology [2].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Mechanistic Diversity

Standardized Workflow for Mechanistic Profiling

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

3.2.1 Advanced Metabolite Profiling and Dereplication Modern NP research employs LC-HRMS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Tandem Mass Spectrometry) coupled with platforms like Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) for comprehensive metabolite annotation [2]. The experimental protocol involves: (1) Preparing natural extracts using standardized extraction protocols (e.g., 1g plant material/10mL solvent); (2) LC separation using reverse-phase columns with water-acetonitrile gradients; (3) HRMS/MS data acquisition in data-dependent acquisition mode; (4) Molecular networking on GNPS platform to visualize structural relationships; (5) Database comparison against Dictionary of Natural Products and other specialized libraries [2]. This workflow efficiently distinguishes novel compounds from known entities, addressing the major challenge of rediscovery in NP research.

3.2.2 Phenotypic Screening with High-Content Imaging For uncovering novel mechanisms, phenotypic screening provides an unbiased approach. The standard protocol includes: (1) Treating disease-relevant cell models (including iPSC-derived cells) with NP fractions; (2) Multi-parameter readouts using high-content imaging systems; (3) Automated image analysis for morphological and subcellular changes; (4) Hit confirmation through dose-response studies [2] [11]. Advanced applications incorporate gene-editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 to create disease-relevant cellular models that enhance physiological relevance [2].

3.2.3 Target Identification via Chemical Proteomics Identifying macromolecular targets is crucial for establishing mechanistic diversity. The non-labeling chemical proteomics approach has emerged as a powerful method: (1) Immobilize the NP of interest on solid support without altering its core structure; (2) Incubate with cell lysates or tissue extracts; (3) Wash away non-specific binders; (4) Elute and identify specifically bound proteins using LC-MS/MS; (5) Validate interactions through orthogonal methods like surface plasmon resonance or cellular thermal shift assays [12]. This approach successfully identifies protein targets without requiring synthetic modification that might alter bioactivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Mechanistic Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Specific Function | Application Context | Key Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-HRMS/MS Systems | High-resolution metabolite separation and identification | Metabolite profiling, dereplication, novelty assessment | Coupling with GNPS enables community-wide data sharing [2] |

| Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) | Crowdsourced annotation of NP spectra | Dereplication, novel compound identification | Open-access platform with growing community contributions [2] |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Disease-relevant cellular models for phenotypic screening | Mechanism discovery in physiological contexts | CRISPR-Cas9 editing enhances disease modeling precision [2] |

| Chemical Proteomics Kits | Target identification without structural modification | Target deconvolution for novel NPs | Non-labeling approaches preserve native bioactivity [12] |

| AI-Based Structure Prediction | In silico target prediction and scaffold optimization | Prioritizing NPs for experimental testing | Models trained on NP-specific data outperform general chemical models [13] |

| Fragment Hotspot Mapping | Identifying binding sites on protein surfaces | Rationalizing NP-protein interactions | Guides mechanistic studies for newly identified NPs [13] |

| Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Tools (AntiSMASH) | Identifying NP biosynthetic pathways | Genome mining for novel NPs | Enables discovery of "cryptic" compounds not produced under standard conditions [5] |

Visualization of Mechanistic Pathways for Representative Natural Products

The diagram illustrates how NPs from different biological sources and structural classes engage entirely distinct mechanistic pathways, underscoring their exceptional value for addressing diverse disease mechanisms. This mechanistic diversity stems from evolutionary selection pressures that have optimized NPs for specific biological interactions unavailable to synthetic compound libraries designed primarily around drug-like property space [5] [1].

Natural products offer unparalleled mechanistic diversity that continues to inspire therapeutic innovation. The experimental data and comparative analyses presented demonstrate that NPs occupy distinct chemical space with structural features evolved for optimal interaction with biological systems. While synthetic compounds excel in optimizing pharmacokinetic properties, NPs provide privileged scaffolds for addressing biologically complex targets and pathways. The future of NP-based mechanistic discovery lies in integrated interdisciplinary approaches that combine advanced analytics, genomic mining, and AI-driven design with robust biological validation [5] [12] [13]. As technological advancements continue to address historical challenges in NP research, particularly in dereplication and sustainable sourcing, these evolutionary-optimized compounds will remain essential for tackling emerging therapeutic challenges, especially in antimicrobial resistance and complex disease pathogenesis.

Natural products (NPs) and their derivatives have long been foundational to pharmacotherapy, particularly in the realms of anti-infectives and anti-cancer treatments [15] [2]. Analysis of drugs approved from 2014 to 2024 reveals that 9.7% (56 of 579) were classified as NPs or NP-derived (NP-D), comprising 44 new chemical entities and 12 antibody-drug conjugates with natural product payloads [15]. Despite this historical success, natural product leads frequently present significant challenges that preclude their direct clinical application, including complex chemical structures, poor absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties, limited specificity, and insufficient potency [13]. These inherent limitations create an imperative for systematic optimization strategies to transform promising natural scaffolds into viable therapeutic agents. This review compares contemporary optimization approaches, evaluating their experimental validation and application in bridging the gap between natural product discovery and drug development.

Strategic Frameworks for Natural Product Optimization

The optimization of natural products employs several distinct strategic paradigms, each with characteristic methodologies and applications. The table below compares the predominant frameworks used in the field.

Table 1: Comparison of Natural Product Optimization Strategies

| Strategy | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Representative Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Modification/Simplification | Direct chemical alteration of native NP structure | Improves ADMET properties and synthetic accessibility | Production of 370 NP-derived drugs (1981-2019) [16] |

| Target-Guided Rational Design | Structural optimization informed by target-binding data (e.g., co-crystals) | Enables precise enhancement of binding affinity and specificity | Geldanamycin → Tanespimycin via Hsp90 co-crystal structure [16] |

| Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) | Generation of complex, NP-inspired libraries from pluripotent intermediates | Rapid exploration of diverse chemical space from NP scaffolds | Discovery of antibiotic gemmacin against MRSA [17] |

| Hybrid Natural Products | Covalent combination of two or more NP pharmacophores | Potential for multi-target activity and enhanced efficacy | Vincristine (hybrid of vindoline and catharanthine) [17] |

| AI-Guided Structural Optimization | Machine learning-driven prediction of optimal structural modifications | Data-driven exploration beyond human chemical intuition | Generative models for target-specific molecule design [13] |

Experimental Platforms for Optimization and Validation

Structural Biology-Driven Optimization

The use of protein-ligand co-crystal structures represents a powerful methodology for rational drug design. This approach provides atomic-resolution insights into molecular interactions between natural products and their biological targets, enabling directed structural modifications [16]. Experimental protocols typically involve:

- Co-crystallization: Formation of crystalline complexes between the target protein and natural product ligand.

- X-ray Diffraction Data Collection: Measurement of diffraction patterns using synchrotron or laboratory X-ray sources.

- Structure Determination: Computational phase determination and model building to generate electron density maps.

- Interaction Analysis: Identification of key hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and steric constraints informing design.

The optimization of geldanamycin to tanespimycin exemplifies this approach. Co-crystal structures with Hsp90 revealed the molecular basis of binding, enabling rational modifications that reduced hepatotoxicity while maintaining potent inhibition [16]. Similarly, structural insights into pactamycin's interaction with the 30S ribosomal subunit enabled synthetic modifications that improved its selectivity toward malarial parasites [16].

Figure 1: Co-crystal Structure-Guided Optimization Workflow

In Silico ADME and Bioactivity Prediction

Computational methods provide cost-effective alternatives for preliminary ADMET screening and bioactivity prediction, addressing key bottlenecks in natural product optimization [18] [19]. Standard protocols include:

- Molecular Docking: Predicts binding orientation and affinity of natural compounds to target proteins using programs like AutoDock Vina or GOLD.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Models time-dependent behavior of protein-ligand complexes to assess binding stability and conformational changes.

- QSAR Modeling: Establishes quantitative relationships between structural descriptors and biological activity to guide optimization.

- PBPK Modeling: Predicts absorption, distribution, and clearance using physiological parameters and compound-specific data.

These methods have been successfully applied to optimize natural compounds like berberine, where computational analysis identified structural modifications that enhanced phospholipase A2 inhibition [16]. Similarly, in silico methods have predicted the antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antimicrobial effects of food-derived natural compounds, guiding subsequent experimental validation [18].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Optimization

| Reagent/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology Resources | Protein Data Bank (PDB), PDBe | Source of 3D protein structures for target-based design [18] |

| Computational Tools | AutoDock, GOLD, SCHRÖDINGER Suite, BIOPEP-UWM, ExPASy | Molecular docking, dynamics, and bioactive peptide analysis [18] |

| Chemical Databases | TCMBank, ETCM, Derwent Innovations Index | Traditional medicine compound libraries and patent information [12] [20] |

| Specialized Screening Libraries | NP-inspired DOS libraries (e.g., 18-scaffold, 242-compound library) | Source of structurally diverse compounds for antibiotic discovery [17] |

| Analytical Platforms | HPLC-HRMS-SPE-NMR, Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking | Metabolite identification and dereplication in complex natural extracts [2] |

Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) for Bioactive Molecule Discovery

Diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS) generates structurally complex libraries from natural product-inspired scaffolds, enabling exploration of underutilized chemical space [17]. A representative protocol for DOS library construction and screening includes:

- Pluripotent Intermediate Design: Synthesis of key intermediates capable of divergent transformation (e.g., solid-supported phosphonate [17]).

- Branching Reaction Pathways: Application of multiple reaction pathways ([3+2] cycloaddition, dihydroxylation, [4+2] cycloaddition) to generate scaffold diversity.

- Library Diversification: Further functionalization through cyclization, annulation, and cross-coupling reactions.

- High-Throughput Screening: Evaluation against biological targets (e.g., MRSA strains) to identify hit compounds.

This approach yielded gemmacin, a novel antibiotic with potent activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) but low cytotoxicity against human epithelial cells [17]. In another application, a DOS library of 2070 macrolactone-inspired compounds identified robotnikin, a potent inhibitor of the Hedgehog signaling pathway with potential anticancer applications [17].

Figure 2: Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) Workflow

Case Studies in Optimization and Clinical Translation

Macrocyclic Immunosuppressants: Rapamycin and FK506

The optimization of rapamycin and FK506 exemplifies target-guided rational design. Co-crystal structures of the FKBP12-rapamycin-FRB ternary complex revealed precise molecular interactions enabling immunosuppressive activity through mTOR inhibition [16]. These structural insights facilitated the development of rapalogs with improved therapeutic profiles, illustrating how atomic-resolution data can guide the optimization of complex natural products for clinical application.

Natural Products as Targeted Cancer Therapies

Natural products have been successfully optimized for targeted cancer therapy, particularly as payloads in antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs). Of the 58 NP-related drugs launched between 2014 and June 2025, 13 were NP-antibody drug conjugates, demonstrating the growing importance of this targeted delivery approach [15]. The optimization process for ADC payloads typically involves structural modifications to enhance potency while maintaining compatibility with antibody conjugation chemistry.

Combatting Antimicrobial Resistance

The pressing challenge of antimicrobial resistance has reinvigorated natural product optimization for antibiotic discovery. Through DOS strategies, researchers have identified novel antibiotics like gemmacin that show potent activity against drug-resistant pathogens such as MRSA [17]. These efforts demonstrate how natural product-inspired synthesis can address evolving medical needs through systematic chemical optimization.

Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives

Artificial Intelligence in Natural Product Optimization

Artificial intelligence (AI) and generative models are revolutionizing natural product optimization through several key applications:

- Target interaction-driven generation: Models like DeepFrag and FREED utilize protein-ligand interaction data to recommend optimal structural modifications [13].

- Molecular growth methods: Approaches such as 3D-MolGNNRL and DiffDec generate molecules directly within target binding pockets, maximizing complementary interactions [13].

- Activity-focused optimization: Models operating without predefined target structures can optimize for desired physicochemical properties and predicted bioactivity [13].

These AI-driven approaches enable more efficient exploration of chemical space around natural product scaffolds, potentially accelerating the optimization process and increasing success rates in drug development.

Integrating Traditional Knowledge with Modern Methods

The continued exploration of traditional medicine pharmacopeias provides valuable sources of pre-validated natural product leads [21]. Modern analytical techniques combined with robust optimization frameworks can systematically investigate these resources, identifying active constituents and enhancing their therapeutic properties through structural optimization.

The journey from natural lead to viable drug remains challenging yet essential for addressing ongoing medical needs. As detailed in this review, successful optimization requires strategic application of multiple complementary approaches—from structural biology-guided design to AI-enabled molecular generation. The imperative for optimization demands rigorous experimental validation across biological systems, with careful attention to ADMET profiling throughout the development process. As technological advances continue to emerge, particularly in computational prediction and structural biology, the efficiency and success rate of natural product optimization will likely increase, reinforcing the enduring value of natural products as privileged starting points for drug discovery.

Design and Synthesis: Strategies for Creating NP-Inspired Libraries

Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) for Skeletal Diversity

Screening collections comprising diverse chemical structures are vital for discovering probes for therapeutic targets, including compounds acting through novel mechanisms of action (nMoA) [22]. Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) is a powerful strategy to prepare molecules with underrepresented features in commercial screening collections, resulting in the elucidation of novel biological mechanisms [22]. A central challenge in modern chemical genetics and drug discovery is the design and synthesis of libraries that span large tracts of biologically relevant chemical space [23]. This challenge has spawned the field of DOS, whose synthetic challenges differ significantly from target-oriented synthesis. DOS methods must be sufficiently robust to prepare diverse compounds simultaneously, deliberately, and combinatorially, typically in up to five highly reliable synthetic steps with little or no scope for protecting group chemistry [23].

The structural diversity of a small-molecule library directly correlates with its functional diversity, which is proportional to the amount of chemical space the library occupies [24]. There is a widespread consensus that increasing the scaffold diversity in a small-molecule library is one of the most effective ways to increase its overall structural diversity [24]. Small multiple-scaffold libraries are generally regarded as superior to large single-scaffold libraries in terms of bio-relevant diversity [24]. Compounds based on different molecular skeletons display chemical information differently in three-dimensional space, increasing the range of potential biological binding partners for the library as a whole [24]. This review comprehensively compares contemporary DOS strategies for achieving skeletal diversity, their experimental validation, and their application in discovering novel bioactive compounds.

Comparative Analysis of DOS Strategies for Skeletal Diversity

DOS strategies are broadly categorized by their approach to generating structural variation. The following comparison examines the core methodologies, their implementation, and their outputs.

Table 1: Comparison of Core DOS Strategies for Generating Skeletal Diversity

| Strategy | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Skeletal Diversity Outcome | Representative Library Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branching Pathways [22] [25] | Uses a common starting material and divergent reaction sequences to generate distinct scaffolds. | High scaffold diversity from single starting point; mimics biosynthetic pathways. | Multiple, distinct molecular skeletons from a common intermediate. | 3.7 million-member DEL [22] |

| Stereochemical Diversification [24] | Utilizes robust asymmetric transformations to create stereoisomers around a common core. | Systematically explores 3D space; high impact on biological activity. | Single core scaffold with high stereochemical variation. | Varies (often 10s-100s of compounds) |

| Appendage Diversification [24] | Employs reliable coupling reactions to vary substituents around a common skeleton. | Simplicity and reliability using known chemistry; high compound numbers. | Single core scaffold with high substitutional variation. | Very large (often millions in DELs) |

| Late-Stage Functionalization [26] | Employs selective reactions (e.g., P450 catalysis) on pre-formed complex cores. | Introduces complexity and new vectors without de novo synthesis. | Modified core scaffolds with new functional handles for further diversification. | >50 members [26] |

The Branching Pathway Strategy: DOSEDO

The DOSEDO (Diversity-Oriented Synthesis Encoded by Deoxyoligonucleotides) approach exemplifies the branching pathway strategy. It uses a "single pharmacophore library" design where successive steps of appendage diversification of a common skeleton are recorded by DNA barcodes [22]. However, it expands this by employing multiple skeletal elements with consistent reactivity, allowing simultaneous appendage diversification using a common set of diverse appendages [22].

Experimental Protocol for DOSEDO Library Construction [22]:

- Skeleton Selection: 61 multifunctional compounds serve as skeletons, all comprising secondary amines (Fmoc-, Boc- or Ns-protected) and an aryl halide (Br or I). Each skeleton bears either a carboxylic acid or primary hydroxyl group as the site of DNA attachment.

- DNA Linkage:

- Acid-functionalized skeletons: Coupled to amine-functionalized DNA under optimized conditions to minimize material usage.

- Hydroxyl-functionalized skeletons: Activated with N,N′-disuccinimidyl carbonate (DSC), filtered, and incubated with amine-functionalized DNA.

- Skeleton Diversification:

- Amine Capping: Acylation, sulfonylation, and reductive amination were optimized. Post-HPLC acetate residue was minimized through multiple EtOH precipitation washes or ultrafiltration to prevent acetylation byproducts.

- Aryl Halide Diversification: Suzuki coupling with boronic acid/ester building blocks. Optimization of 288 reactions identified PdCl₂(dppf)·CH₂Cl₂ in a 1:1 EtOH/MeCN mixture as the preferred catalyst system for high conversion and minimal variability.

- Building Block Validation: Amine-capping building blocks were profiled using HPLC-purified Pro-DNA. Only building blocks with >70% area-under-the-curve (AUC) conversion to the desired product and <10% AUC unknown species were included in the final library.

This process resulted in a 3.7 million-member DEL with significant skeletal and exit vector diversity beyond what is possible by varying appendages alone [22].

Natural Product-Inspired and Biomimetic Strategies

Natural products inherently populate biologically relevant chemical space, as they must bind their biosynthetic enzymes and their target macromolecules [23]. Consequently, natural product families are "libraries of pre-validated, functionally diverse structures" where individual compounds can selectively modulate unrelated targets [23]. DOS strategies often leverage this principle.

One approach harnesses R-tryptophan as a chiral auxiliary to build architecturally diverse chiral molecules. The synthesis involves converting methyl ester 1 to 1-aryl-tetrahydro-β-carbolines 2a–d, which are then transformed into chiral compounds via intermolecular and intramolecular ring rearrangements [27]. This DOS strategy generated four distinct molecular classes, comprising nearly twenty-two individual molecules, with phenotypic screening revealing selective cytotoxicity against MCF7 breast cancer cells (IC₅₀ ∼5 μg mL⁻¹) [27].

A more recent biomimetic strategy employs late-stage P450-catalyzed oxyfunctionalization. This method integrates regiodivergent, site-selective P450 enzymes with divergent chemical routes for skeletal diversification and rearrangement of a parent molecule [26]. The library, comprising over 50 members equipped with an electrophilic warhead for covalent target engagement, exhibits broad chemical and structural diversity and includes several compounds with selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells and diversified anticancer activity profiles [26].

Diagram 1: Natural Product-Inspired DOS Workflow

Analytical and Chemoinformatic Evaluation of Diversity

Evaluating the success of a DOS campaign in achieving skeletal diversity requires robust analytical methods. Chemoinformatic analysis has become a standard tool for this purpose.

For a library of morpholine peptidomimetics, researchers used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to explore the chemical space. The web-based public tool ChemGPS-NP was used to position compounds onto a consistent 8-dimensional map of structural characteristics, with the first four dimensions capturing 77% of data variance [25]. This analysis allows for the comparison of new compounds against an in-house library to determine if they occupy novel or undersampled regions of chemical space.

Another critical metric is the fraction of sp³ (Fsp³) carbon atoms, defined as the number of sp³ hybridized carbons divided by the total carbon count [25]. A higher Fsp³ character is generally associated with increased molecular complexity and is a common feature of natural products and successful drugs [24]. DOS libraries aiming for natural product-like characteristics often prioritize synthetic routes that yield molecules with a higher Fsp³ fraction.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Representative DOS Campaigns for Skeletal Diversity

| DOS Approach / Library | Key Skeletal Diversification Reaction(s) | Number of Scaffolds / Core Structures | Reported Biological Validation & Hit Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOSEDO (DNA-Encoded) [22] | Suzuki coupling, acylation, sulfonylation, reductive amination on 61 cores. | 61 multifunctional skeletons | Screening against 3 diverse protein targets yielded validated binders. |

| P450 Late-Stage [26] | P450-catalyzed C-H oxyfunctionalization & rearrangement. | Multiple from parent scaffold | Several compounds with selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells. |

| Morpholine Peptidomimetics [25] | Multicomponent reactions, Staudinger, alkylation, trans-acetalization. | >10 distinct bicyclic & tricyclic morpholine-based scaffolds | Active as aspartyl protease inhibitors (SAP2, HIV, BACE1) and RGD integrin ligands. |

| Natural Product-Inspired (R-Tryptophan) [27] | Ring rearrangements, intermolecular & intramolecular cyclizations. | 4 distinct molecular classes | Two molecules selectively inhibited MCF7 breast cancer cells (IC₅₀ ~5 μg mL⁻¹). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Implementing DOS for skeletal diversity requires specialized reagents and building blocks. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DOS Implementation

| Reagent / Material | Function in DOS | Application Example | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multifunctional Skeletons | Core building blocks bearing orthogonal reactive groups for diversification. | Skeletons with aryl halides and protected amines for cross-coupling and amine capping [22]. | Consistent reactivity across different skeletons enables use of common building block sets. |

| DNA Tags & Conjugates | Encoding individual compounds in a library for affinity-based screening. | Tracking synthetic history in DEL synthesis via split-and-pool combinatorial chemistry [22]. | DNA compatibility is a major constraint; reactions must be mild (aqueous environment, limited heat/pH). |

| PdCl₂(dppf)·CH₂Cl₂ | Palladium catalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling. | Diversifying aryl bromides/iodides on skeletons in the DOSEDO library [22]. | Selected for high conversion and least variable outcomes across temperatures and solvents (MeCN/EtOH). |

| Chiral Pool Building Blocks | Providing stereochemical and functional diversity from natural sources. | Amino acids (R-Tryptophan [27]) and sugars [25] as starting materials for complexity-generating reactions. | Enables efficient access to stereochemically dense, sp³-rich scaffolds with defined stereocenters. |

| Engineed P450 Enzymes | Catalyzing late-stage, site-selective C-H oxyfunctionalization. | Introducing oxygenated functional handles on complex cores for further diversification [26]. | Provides a powerful, biomimetic method to increase complexity and access new scaffolds. |

| N,N′-Disuccinimidyl Carbonate (DSC) | Activating hydroxyl groups for conjugation to amine-functionalized DNA. | Creating a stable carbamate linkage between hydroxyl-bearing skeletons and DNA [22]. | Activated skeletons must be purified (e.g., silica filtration) before DNA conjugation. |

DOS has established itself as an indispensable strategy for generating skeletal diversity, moving beyond traditional combinatorial chemistry's focus on appendage variation. As evidenced by the compared strategies—from the massively parallel DNA-encoded DOSEDO approach to the elegant, biosynthetically inspired late-stage functionalization—the field continues to develop innovative methods to populate biologically relevant chemical space. The consistent success of these libraries in yielding high-quality, validated hits against a range of protein targets and in phenotypic assays underscores the validity of pursuing skeletal diversity as a central goal in chemical library synthesis. The ongoing integration of chemoinformatic analysis ensures that DOS libraries are not only synthetically diverse but also effectively explore distinct regions of chemical space, accelerating the discovery of novel probes and therapeutic leads, particularly for challenging "undruggable" targets.

Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS) for Guided Exploration

Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS) is a systematic approach for exploring biologically relevant chemical space by using natural product (NP) scaffolds as guiding starting points for the design of compound libraries [4]. This strategy is grounded in the recognition that natural products, honed by millions of years of evolutionary selection, possess inherent biological relevance and optimal structural properties for interacting with biomolecules [5] [4]. BIOS operates on the principle that nature provides the most reliable guide for discovering new bioactive compounds, as NPs "explore biologically relevant chemical space and encod[e] inherent biological relevance, as a result of their ability to bind biomolecules and cross cell membranes" [4]. The core hypothesis of BIOS is that scaffolds derived from natural products will yield higher hit rates in biological screening and are more likely to produce compounds with favorable absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties compared to purely synthetic compounds or combinatorial libraries [4]. This approach stands in contrast to conventional synthesis (CS) or combinatorial library synthesis (CLS), which often prioritize synthetic accessibility over biological pre-validation, and differs from diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS) by its specific focus on naturally occurring scaffolds rather than broader structural diversity [4]. By bridging the gap between the rich structural diversity of natural products and the practical requirements of modern drug discovery, BIOS provides a powerful framework for navigating the vast landscape of possible chemical structures while maximizing the potential for identifying meaningful biological activity.

Comparative Analysis of BIOS Against Alternative Strategies

Strategic Positioning and Key Differentiators

BIOS occupies a distinctive position in the landscape of compound library design strategies, balancing evolutionary guidance with practical synthetic considerations. The following table compares BIOS against other prominent approaches for exploring chemical space in drug discovery.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Compound Library Design Strategies

| Strategy | Guiding Principle | Chemical Space Coverage | Typical Scaffold Origin | Relative NP Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOS | Uses validated NP scaffolds | Focused around biologically relevant regions | Actual NP scaffolds | High |

| Conventional Synthesis (CS) | Target-oriented synthesis | Single compound focus | Synthetic or NP | Variable |

| Combinatorial Library Synthesis (CLS) | Rapid access to many compounds | Limited diversity within library | Often synthetic | Low |

| Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) | Maximize structural diversity | Broad, diverse regions | Often synthetic | Moderate |

| Pseudo-Natural Product (PNP) | Recombine NP fragments | Novel combinations of NP fragments | NP fragments | Moderate |

| Function-Oriented Synthesis (FOS) | Optimize function of lead NP | Focused around lead NP | NP-derived | High |

BIOS distinguishes itself through its strategic focus on actual NP scaffolds rather than synthetic frameworks or NP fragments [4]. This scaffold selection criterion provides BIOS with a significant advantage: the starting points have already been evolutionarily pre-validated for biological relevance. As noted by Bro and Laraia, "BIOS is for the most part based on actual NP scaffolds, thus bringing the resulting analogues closer to NPs compared to DOS and PNP" [4]. This strategic positioning enables researchers to explore chemical space with greater confidence in the biological relevance of their compounds while still allowing for structural modifications that can improve properties such as solubility, metabolic stability, or target selectivity.

Performance Metrics and Experimental Validation

The practical utility of BIOS is demonstrated through its performance in biological screening campaigns and its ability to produce compounds with favorable physicochemical properties. The table below summarizes key experimental data from studies employing BIOS and related strategies.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of BIOS and Alternative Strategies

| Strategy | Reported Hit Rates | Complexity (Fsp³) | Selectivity Profile | Synthetic Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOS | Higher hit rates in phenotypic screens [4] | High (NP-like) | Correlated with increased selectivity [4] | Moderate to high |

| Conventional Synthesis | Variable | Variable | Variable | High |

| Combinatorial Libraries | Generally low | Lower than NPs | Often promiscuous binders | Very high |

| DOS/pDOS | Moderate | High (by design) | Moderate to high | Moderate |

| PNP/dPNP | Moderate to high | Moderate | Early stage investigation | Moderate |

Experimental evidence supports the superior performance of BIOS in identifying biologically active compounds. The higher Fsp³ character (fraction of sp³-hybridized carbons) typical of BIOS-derived compounds correlates with improved selectivity, as "increased complexity has been correlated with increased selectivity" [4]. However, it is important to note that "complexity alone does not guarantee bioactivity," and BIOS maintains a careful balance of molecular parameters to ensure drug-like properties [4]. The strategic advantage of BIOS is further evidenced by its ability to produce compounds that inhabit the desirable chemical space between purely synthetic molecules and unmodified natural products, combining biological relevance with synthetic accessibility and optimization potential.

Experimental Protocols for BIOS Implementation

Core Workflow and Methodology

Implementing BIOS requires a systematic approach that integrates principles of natural product chemistry with modern synthetic and analytical techniques. The following diagram illustrates the core BIOS workflow:

The BIOS workflow begins with careful selection of natural product templates based on their biological profiles, structural features, and synthetic accessibility [4]. The process continues with identification of the core scaffold that embodies the essential structural elements responsible for the natural product's bioactivity. Retrosynthetic analysis then deconstructs this scaffold into synthetically accessible building blocks, enabling the design of a diverse library that maintains the core NP scaffold while introducing strategic structural variations. Synthesis and thorough characterization follow, employing modern analytical techniques to confirm structural identity and purity. Biological screening against relevant targets or phenotypic assays then evaluates the library's activity, followed by detailed structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis to guide further optimization through iterative cycles of design and synthesis.

Practical Implementation and Case Examples

A representative BIOS protocol for generating a compound library based on the sterol alkaloid cyclopamine would proceed as follows: First, select cyclopamine as the guiding natural product due to its potent Hedgehog pathway inhibition and interesting steroidal scaffold. Identify the rigid steroidal framework with specific hydroxyl and amine functionalities as the core scaffold. Perform retrosynthetic analysis to identify key disconnections that allow for modular synthesis with variation points. Design a library that maintains the essential steroidal framework while systematically varying substituents at positions identified as tolerant to modification. Synthesize the library using solid-phase or solution-phase techniques, employing key reactions such as Michael additions, reductive aminations, and Suzuki couplings to introduce diversity. Characterize all compounds using LC-MS and NMR to confirm purity and structure. Screen the library against the Hedgehog signaling pathway using a Gli-luciferase reporter assay, with Smoothened agonist SAG as a positive control. Analyze SAR to identify key structural features required for activity, then design and synthesize a focused second-generation library to optimize potency and selectivity.

This systematic approach has proven successful in multiple research contexts. For instance, BIOS has been applied to discover novel inhibitors of sterol transport proteins through synthesis of sterol-inspired libraries, demonstrating the strategy's utility in targeting biologically relevant processes [4]. The power of BIOS lies in its balanced approach, maintaining the biological relevance inherent to natural product scaffolds while allowing sufficient structural variation to optimize properties and explore structure-activity relationships.

Essential Research Toolkit for BIOS

Successful implementation of BIOS requires access to comprehensive biological and chemical databases that inform natural product selection and scaffold design. The table below details essential resources for BIOS research.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Biology-Oriented Synthesis

| Resource Category | Specific Databases/Tools | Key Function in BIOS | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | PubChem, ChEBI, ChEMBL, ZINC [28] | NP structure retrieval and bioactivity data | Publicly accessible |

| Reaction/Pathway Databases | KEGG, Reactome, MetaCyc, Rhea [28] | Biological context and pathway analysis | Publicly accessible |

| Enzyme Databases | BRENDA, Uniprot, PDB [28] | Target identification and binding site analysis | Publicly accessible |

| Structural Databases | PDB, AlphaFold Protein Structure DB [28] | 3D structure analysis and docking studies | Publicly accessible |

| Specialized NP Databases | NPAtlas, LOTUS, COCONUT, NPASS [28] | Focused natural product information | Publicly accessible |

These databases provide the foundational information required for informed natural product selection and scaffold design in BIOS. For example, KEGG and Reactome offer insights into the biological pathways and processes associated with natural products of interest [28]. Structural databases like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and AlphaFold Protein Structure Database enable structure-based design approaches by providing three-dimensional structural information on potential biological targets [28]. Specialized natural product databases such as NPAtlas and LOTUS offer curated information on natural product structures, sources, and bioactivity data, facilitating the identification of promising starting points for BIOS campaigns [28].

The experimental implementation of BIOS requires access to synthetic chemistry tools, analytical instrumentation, and screening capabilities. Key resources include modern synthetic chemistry equipment for performing reactions under inert atmosphere, heating, cooling, and microwave irradiation when needed. Automated chromatography systems can significantly accelerate purification steps during library synthesis. Essential analytical instrumentation includes LC-MS systems for purity assessment and structural confirmation, with high-resolution mass spectrometry providing accurate mass data for compound characterization. NMR instrumentation (¹H, ¹³C, and 2D techniques) is crucial for structural elucidation and confirmation of compound identity. For biological evaluation, access to high-throughput screening facilities with plate readers, liquid handling systems, and cell culture capabilities enables comprehensive biological profiling. Additionally, computational resources for molecular modeling, docking studies, and chemoinformatic analysis support the design and optimization phases of BIOS campaigns.

Advanced structural biology tools are increasingly important for BIOS applications. Recent developments in protein structure prediction, such as AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3, have enhanced capabilities for predicting structures of individual proteins and complexes [29]. Experimental techniques like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) provide complementary structural information, with ProFusion representing an innovative approach that "integrates a deep learning model with AFM" for 3D reconstruction of protein complex structures [29]. These structural insights can guide the design of BIOS libraries targeting specific protein complexes or interaction interfaces.

BIOS in the Context of Emerging Technologies

Integration with Artificial Intelligence and Automation

The integration of BIOS with artificial intelligence (AI) and automation technologies represents a powerful convergence that accelerates and enhances the compound discovery process. AI-driven approaches are transforming synthetic biology and chemical design, with machine learning algorithms now capable of parsing "massive datasets of genetic sequences, protein structures, metabolic pathways, and CRISPR tools" to resolve complex biological engineering problems [30]. These technologies align exceptionally well with the BIOS paradigm, as they can identify patterns in natural product bioactivity and structural features that might escape human researchers. For instance, large language models like ChatGPT-4 have demonstrated utility in generating experimental code and design scripts, dramatically reducing the time required for protocol development [31]. The integration of AI with automated synthesis and screening platforms creates a powerful Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle that iteratively refines BIOS libraries based on experimental data [31]. As noted in studies of automated workflows, this approach can achieve "a 2- to 9-fold increase in yield was achieved in just four cycles" when applied to biological optimization problems [31].

The synergy between BIOS and AI extends to predictive modeling of compound properties and bioactivity. Machine learning models can analyze the structural features of natural product scaffolds and predict which modifications are likely to maintain or enhance biological activity while improving drug-like properties. This capability is particularly valuable for navigating the complex balance between structural complexity, bioactivity, and physicochemical properties that BIOS must maintain. As AI technologies continue to mature, their integration with BIOS promises to further increase the efficiency and success rate of natural product-inspired drug discovery.

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

BIOS continues to evolve with emerging technologies and methodologies. One significant development is the increasing integration of BIOS principles with targeted protein degradation approaches, as exemplified by the discovery of "a drug-like, natural product-inspired DCAF11 ligand chemotype" [32]. This work demonstrates how natural product-inspired compounds can provide novel tools for chemical biology, in this case enabling exploration of "this E3 ligase in chemical biology and medicinal chemistry programs" [32]. The discovery that an arylidene-indolinone scaffold—a structure frequently occurring in natural products—could serve as a ligand for DCAF11 raises the possibility that "E3 ligand classes can be found more widely among natural products and related compounds" [32], highlighting the continued potential of BIOS to reveal new biological insights and therapeutic strategies.

Future applications of BIOS will likely expand beyond traditional small molecule drug discovery to include the design of chemical probes for emerging target classes, substrates for enzyme engineering, and compounds for manipulating cellular processes like targeted protein degradation. The principles of BIOS are also being extended to new molecular modalities, including peptides and macrocycles, further expanding the accessible chemical space for drug discovery. As structural biology techniques advance, providing deeper insights into protein-ligand interactions, BIOS will continue to evolve as a powerful strategy for bridging the gap between nature's chemical innovations and modern therapeutic development.

Hybrid Natural Products and Scaffold Merging

Natural products (NPs) have served as a cornerstone of pharmacotherapy for centuries, particularly in the areas of anti-infectives and anticancer agents. Nearly one-third of FDA-approved drugs from 1981 to 2019 originated from natural products or their derivatives, underscoring their profound impact on modern medicine [13] [2]. These evolutionarily optimized molecules explore biologically relevant chemical space and possess inherent biological relevance due to their ability to bind biomacromolecules and cross cell membranes [4]. However, NPs often present challenges that limit their direct clinical application, including complex stereochemical architectures, unfavorable ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties, and insufficient biological activity or specificity for therapeutic targets [13].

To address these limitations while preserving the privileged structural features of NPs, medicinal chemists have developed innovative strategies for structural modification. Among these approaches, the creation of hybrid natural products (HNPs) and scaffold merging have emerged as powerful methodologies for generating novel bioactive entities [17]. These techniques involve the rational combination of either entire NP scaffolds or distinct pharmacophoric elements from multiple NP classes into single molecular entities. The resulting hybrids aim to leverage the complementary biological activities and physicochemical properties of their parent structures, potentially yielding compounds with enhanced efficacy, improved safety profiles, and the ability to overcome drug resistance mechanisms [17] [4].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of hybrid natural product strategies, focusing on their implementation, experimental validation, and role in confirming the biological relevance of natural product-inspired drug discovery.

Strategic Approaches to Hybrid Natural Product Design

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

The design of hybrid natural products encompasses several distinct but complementary strategies:

Molecular Hybridization: The covalent fusion of two or more pharmacophoric elements from distinct bioactive compounds to generate a new hybrid molecule with enhanced affinity and efficacy compared to the parent structures [33]. This approach can produce compounds with altered selectivity, dual mechanisms of action, and reduced side effects.

Scaffold Merging: The integration of core structural frameworks from different natural products to create novel chemotypes that occupy previously unexplored chemical space while maintaining biological relevance [4].

Pseudo-Natural Products (PNPs): The recombination of NP fragments into novel molecular scaffolds not found in nature, guided by the principle that fragments from biologically validated NPs are more likely to produce bioactive compounds compared to purely synthetic fragments [4].

These strategies are underpinned by the conceptual framework of the "informacophore," which extends traditional pharmacophore models by incorporating data-driven insights derived not only from structure-activity relationships (SAR), but also from computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure [34]. This fusion of structural chemistry with informatics enables a more systematic and bias-resistant strategy for scaffold modification and optimization.

Quantitative Validation of the Natural Product Foundation