The Three Pillars of Natural Product Dereplication: Integrating Taxonomy, Spectroscopy, and Structures for Efficient Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the three pillars of natural product dereplication—biological taxonomy, spectroscopic signatures, and molecular structures—targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Three Pillars of Natural Product Dereplication: Integrating Taxonomy, Spectroscopy, and Structures for Efficient Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the three pillars of natural product dereplication—biological taxonomy, spectroscopic signatures, and molecular structures—targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores foundational concepts, methodological applications, troubleshooting strategies, and validation techniques, covering workflows from database utilization to advanced analytical tools like NMR and MS, with the aim of accelerating drug discovery from natural sources.

Laying the Groundwork: Understanding the Core Pillars of Dereplication

Defining Natural Product Dereplication and Its Critical Role in Drug Discovery

The rediscovery of known compounds has historically been a significant and costly bottleneck in natural product (NP) research, consuming valuable time and resources in the isolation and re-elucidation of already characterized molecules [1]. Dereplication, defined as the rapid identification of previously reported compounds within a complex mixture, has thus emerged as a critical, upfront strategy to streamline the discovery pipeline [2]. Its primary role is to triage extracts, allowing researchers to focus efforts and resources on truly novel chemistry with the potential for new bioactivity.

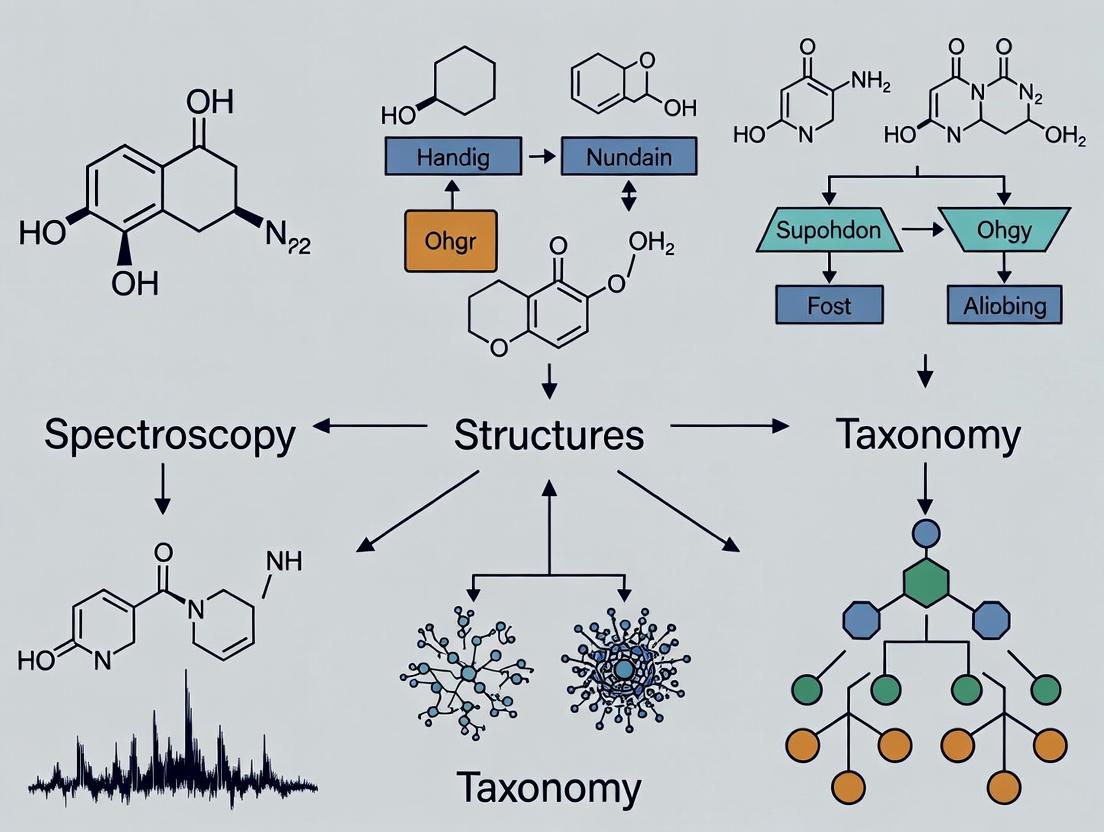

This process is fundamentally framed within the three-pillar paradigm of dereplication, which integrates: 1) the biological taxonomy of the source organism, 2) the spectroscopic and spectrometric signatures of metabolites, and 3) comprehensive databases of known molecular structures [3]. The convergence of these pillars enables a probabilistic and efficient filtering strategy, moving from the broad universe of all known NPs to a much smaller, taxonomically informed candidate list that can be matched against analytical data. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of dereplication methodologies, experimental protocols, and essential tools, underscoring its indispensable function in accelerating the discovery of new therapeutic leads from nature.

The Conceptual Foundation: The Three Pillars of Dereplication

Effective dereplication is not reliant on a single technique but on the strategic integration of three core informational domains. The interdependence of these pillars creates a robust framework for efficient compound identification.

- Taxonomy (The Biological Context): The taxonomic classification of the source organism provides a powerful first filter. Secondary metabolism is genetically encoded, meaning phylogenetically related organisms often produce structurally similar or identical specialized metabolites [3]. Restricting initial database searches to compounds reported from the same genus or family dramatically reduces the number of candidate structures, increasing the speed and confidence of identification [4].

- Spectroscopy (The Analytical Fingerprint): This pillar encompasses the empirical data used for direct comparison, primarily from mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. High-Resolution MS (HRMS) delivers exact molecular formulas, while tandem MS (MS/MS) provides fragmentation patterns indicative of structural motifs [1]. NMR, particularly ¹³C NMR, offers highly specific structural information about the carbon skeleton, with chemical shifts that are predictable and less susceptible to solvent effects than ¹H NMR [4].

- Structures (The Reference Library): This pillar consists of the curated databases linking chemical structures to taxonomic origin and, ideally, to associated spectroscopic data. The utility of dereplication is directly proportional to the comprehensiveness and accuracy of these databases. Key resources include the fully open-source LOTUS database, which explicitly links structures to taxonomy, and COCONUT, a large collection of unique NP structures [4] [3]. The absence of experimental spectra in many databases is increasingly mitigated by the use of in-silico prediction tools for NMR and MS/MS data [4].

The following diagram illustrates how these three pillars interact within a dereplication workflow, guiding the process from a raw extract to a confident compound annotation.

Diagram 1: The Three-Pillar Dereplication Workflow Logic. This diagram shows how taxonomy filters the structural database to create a candidate list, which is then matched against experimental spectroscopic data for identification.

Core Analytical Methodologies and Protocols

Modern dereplication employs hyphenated analytical techniques that separate complex mixtures and provide rich spectroscopic data for component identification.

Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS/MS)

LC-HRMS/MS is the cornerstone of high-throughput dereplication, enabling the profiling of hundreds of compounds in a single analysis.

Experimental Protocol: Building an In-House MS/MS Library for Dereplication [1]

- Standard Pooling: Select analytical standards of target compound classes. Group standards into pools based on log P values and exact masses to minimize co-elution and isomer interference during LC-MS analysis.

- LC-HRMS/MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Use a C18 reversed-phase column. Employ a gradient elution with water (with 0.1% formic acid) and acetonitrile as mobile phases.

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate in positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode. Acquire HRMS data for accurate mass.

- MS/MS Acquisition: For each pool, acquire MS/MS spectra using both [M+H]⁺ and [M+Na]⁺ adducts. Use a data-dependent acquisition (DDA) method, fragmenting the top ions at multiple collision energies (e.g., 10, 20, 30, 40 eV) to capture comprehensive fragmentation patterns.

- Library Construction: Process data to extract for each compound: name, molecular formula, exact mass, retention time, and all associated MS/MS spectra. Compile into a searchable library format.

- Dereplication Application: Analyze crude extracts under identical LC-MS conditions. Use the library to search for matches based on retention time, exact mass (error < 5 ppm), and MS/MS spectral similarity.

Advanced Strategy: Molecular Networking Molecular networking (MN) on platforms like Global Natural Products Social (GNPS) is a powerful untargeted extension of MS/MS dereplication [5]. It visualizes relationships between compounds in an extract based on spectral similarity, clustering analogs and known compounds together. This allows for the annotation of entire compound families based on the annotation of a single node in the network and prioritizes unique clusters for novel chemistry [2] [5].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy and Database Creation

While less sensitive than MS, NMR provides highly definitive structural information, making it crucial for final confirmation. ¹³C NMR is particularly valuable for dereplication due to its wide spectral dispersion and predictable chemical shifts [4].

Experimental Protocol: Creating a Taxon-Specific ¹³C NMR Database [4] This protocol details the creation of a focused database for a specific organism (e.g., Brassica rapa).

- Structure Retrieval: Query the LOTUS database using the organism's scientific name. Download all associated chemical structures in SDF format.

- Structure Curation: Use Python scripts (e.g., RDKit) to clean the structure file:

- Remove duplicate entries.

- Correct tautomeric forms (e.g., convert iminols to amides).

- Standardize atom valence representations for compatibility with prediction software.

- Chemical Shift Prediction: Import the curated SDF file into a prediction software (e.g., ACD/Labs CNMR Predictor). Batch-calculate the ¹³C NMR chemical shifts for every structure in the library.

- Database Deployment: Export the structures and their predicted shifts into a dedicated, searchable database (e.g., as an SDF file with chemical shift tags). This taxon-focused database can now be used to rapidly search experimental ¹³C NMR data from a purified compound or fraction.

Integrated and Bioactivity-Guided Workflows

Cutting-edge approaches combine chemical analysis with biological screening to dereplicate specifically the bioactive constituents.

Protocol: Integrated Online DPPH-Assisted Dereplication [6] This workflow identifies antioxidant compounds directly in mixtures.

- Fractionation: First, fractionate the crude extract using Centrifugal Partition Chromatography (CPC) to reduce complexity.

- Online Bioactivity Screening: Subject CPC fractions to LC-MS analysis where the effluent is split. One stream goes to the MS, the other passes through a reaction coil containing the stable radical DPPH•. A UV detector monitors the DPPH• bleaching, indicating radical-scavenging activity.

- Correlated Analysis: The MS data (retention time, MS/MS spectrum) of a peak is directly correlated with a dip in the DPPH• trace, pinpointing the exact compound responsible for antioxidant activity.

- Confidence Annotation: Use tools like CATHEDRAL to integrate the HRMS/MS data and any available NMR data, assigning a confidence level to the annotation of the active compound [6].

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from recent dereplication studies employing these methodologies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics from Recent Dereplication Studies

| Study Focus | Methodology | Sample/Organism | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS/MS Library Development | LC-HRMS/MS, in-house library | 31 standard phytochemicals | Library enabled dereplication in 15 food/plant extracts with <5 ppm mass error. | [1] |

| Molecular Networking | LC-MS/MS, GNPS-based MN | Sophora flavescens root extract | 51 compounds annotated; DIA and DDA data were complementary. | [5] |

| Bioactivity-Guided | Online DPPH, LC-HRMS/MS, NMR | Makwaen pepper by-product | 50 antioxidant compounds identified, 10 first reports for the genus. | [6] |

| NMR Database Creation | LOTUS + ¹³C NMR prediction | Brassica rapa (Turnip) | Created a taxon-specific DB with predicted shifts for 120 compounds. | [4] |

Successful dereplication relies on a combination of physical reagents, software, and data resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Dereplication

| Category | Item/Resource | Function in Dereplication |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography & Separation | C18 Reversed-Phase U/HPLC Columns | High-resolution separation of complex natural extracts prior to MS or NMR detection. |

| Centrifugal Partition Chromatography (CPC) | Solvent-based fractionation technique for gentle, high-capacity separation of crude extracts [6]. | |

| Mass Spectrometry | High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer (Q-TOF, Orbitrap) | Provides exact mass measurement for molecular formula determination (<5 ppm error is standard) [1]. |

| Analytical Standards (e.g., flavonoid, alkaloid libraries) | Used to build in-house MS/MS spectral libraries for targeted dereplication [1]. | |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance | Deuterated Solvents (CD₃OD, DMSO-d₆) | Required for acquiring NMR spectra; provides a deuterium lock and minimal interfering signals. |

| NMR Prediction Software (e.g., ACD/Labs CNMR Predictor) | Generates predicted ¹³C NMR chemical shifts for database creation when experimental data is absent [4]. | |

| Bioactivity Screening | DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Stable radical used in online or offline assays to detect antioxidant compounds directly in LC effluents [6]. |

| Data Analysis & Databases | GNPS (Global Natural Products Social) | Web-based platform for mass spectrometry data sharing, molecular networking, and library searches [5]. |

| LOTUS Database (lotus.naturalproducts.net) | Open-source database linking NP structures to taxonomic origin, essential for taxon-focused searches [4]. | |

| RDKit Cheminformatics Toolkit | Open-source software for manipulating chemical structures (e.g., standardization, tautomer correction) during database curation [4]. | |

| MZmine / MS-DIAL | Open-source software for processing LC-MS data, including feature detection, alignment, and export for GNPS [5]. |

Natural product dereplication has evolved from a simple avoidance tactic into a sophisticated, integrated discipline that is the critical gatekeeper of efficiency in drug discovery. By systematically applying the three-pillar framework—leveraging taxonomy, spectroscopy, and structural databases—researchers can swiftly discard known entities and concentrate resources on promising novel leads.

The future of dereplication lies in deeper automation and artificial intelligence. Machine learning models are being trained to predict MS/MS spectra and NMR shifts with greater accuracy, while also mining genomic data to predict biosynthetic pathways and their products [2]. The continued expansion and open sharing of curated, high-quality spectral databases will be paramount. Furthermore, the tight integration of bioactivity screening with real-time chemical analysis, as seen in online assays, will make dereplication not just about identity, but also about function, ensuring that the novel compounds prioritized are also biologically relevant. In this way, dereplication remains the essential engine that powers the sustainable and rational discovery of new medicines from nature's vast chemical repertoire.

1. Introduction: The Imperative of Dereplication in Natural Product Research

The investigation of natural products (NPs) for drug discovery and chemical innovation is fundamentally constrained by the challenge of redundancy. A significant proportion of bioactivity detected in crude extracts originates from already known compounds. Dereplication—the rapid identification of known entities—is therefore a critical, efficiency-driven discipline designed to prevent the costly re-isolation and re-elucidation of reported molecules [7]. Its successful execution hinges on the integrative use of three core informational pillars: the biological taxonomy of the source organism, the spectroscopic signatures of the compound, and its definitive molecular structure [7]. This guide details the theoretical framework, modern methodologies, and practical tools that unite these pillars into a powerful strategy for accelerating natural product research.

2. Foundational Theory: Interdependence of the Three Pillars

The three pillars are not merely parallel data streams but are deeply interconnected, forming a convergent logic system for identification.

- Taxonomy as a Prior Probability Filter: The evolutionary principle of biosynthetic pathway conservation implies that taxonomically related organisms are more likely to produce chemically similar secondary metabolites [7]. Thus, taxonomy constrains the vast chemical search space (estimated at >400,000 known NPs) to a much smaller, phylogenetically relevant subset, dramatically increasing the odds of correct dereplication [7].

- Spectroscopy as the Empirical Interrogator: Spectroscopic techniques provide the physical data against which candidate structures are matched. NMR and MS are paramount, delivering atomic-level (NMR) and molecular/formula-level (MS) information [7]. The reliability of dereplication scales with the specificity of the spectral data, from molecular formula to full (^{13})C NMR shifts or MS/MS fragmentation patterns.

- Molecular Structure as the Unifying Identifier: The structure is the ultimate endpoint, the unique identifier that connects taxonomic origin (what produces it) to spectroscopic manifestation (how it is detected). Robust structural representation formats (InChI, SMILES, SDF) and their accurate linkage to taxonomic and spectral data in databases are the bedrock of computational dereplication [7].

The synergy is clear: Taxonomy directs the where to look, spectroscopy provides the what to look for, and the molecular structure is the final answer.

3. Quantitative Landscape: Databases and Spectroscopic Metrics

The efficacy of dereplication is quantifiably linked to the scope and quality of underlying databases and the performance metrics of spectroscopic techniques.

Table 1: Key Databases for Natural Product Dereplication

| Database Name | Primary Focus (Pillar) | Key Features & Scope | Utility in Dereplication |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOTUS [4] | Taxonomy-Structure Linkage | Fully open-source; connects ~400k NP structures to organism taxonomy and literature [4]. | Enables creation of taxon-specific candidate lists for targeted searches. |

| COCONUT [7] | Molecular Structure | Large, curated collection of NP structures compiled from multiple sources. | Provides a comprehensive structural reference space. |

| ACD/Lotus & nmrshiftdb2 [8] | Spectroscopy-Structure (NMR) | Combines LOTUS taxonomy with predicted/experimental (^{13})C NMR spectra. ACD/Lotus uses commercial prediction; nmrshiftdb2 is open-access [8]. | Direct spectral searching against a taxonomically informed NMR database. |

| GNPS [7] | Spectroscopy-Structure (MS) | Public platform for MS/MS spectral library matching and molecular networking. | Untargeted metabolite identification via crowd-sourced spectral libraries. |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Core Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Key Measurable Data | Typical Dereplication Power | Limitations / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution MS | Exact mass, Molecular Formula | High-confidence formula assignment. Distinguishes isomers poorly. | Foundation for all further MS-based steps [9]. |

| MS/MS (Tandem MS) | Fragmentation Pattern | High. Library match scores (e.g., cosine score) quantify similarity. | Depends on library coverage; patterns can be instrument-dependent [9]. |

| (^{1})H NMR | Chemical Shift, Coupling, Integration | High for simple mixtures. Susceptible to solvent and pH effects. | Rapid analysis but signals may overlap in complex extracts [7]. |

| (^{13})C NMR | Chemical Shift (typically 0-250 ppm) | Very High. Direct structure fingerprint; 1 signal per C atom. | Lower sensitivity; often requires isolation or enrichment [4] [7]. |

| SERS with ML [10] | Vibrational Fingerprint | >90% accuracy reported for epimer differentiation [10]. | Requires specific substrate/functionalization; emerging technique. |

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Dereplication Workflows

| Workflow Name/Type | Core Input Data | Search Space Constraint Method | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomy-Focused (^{13})C NMR DB [4] [8] | Experimental (^{13})C NMR shifts of isolate/mixture | Pre-filtered database of NPs from a specific taxon (e.g., genus Brassica). | Efficient retrieval of known structures from the target organism group. |

| Forward-Predictive SERS Taxonomy [10] | SERS spectrum of an unknown epimer | Hierarchical ML model deduces structural features (e.g., sugar type, chain length) stepwise. | Untargeted identification and quantification with <10% error for cerebrosides [10]. |

| Multiplexed Chemical Metabolomics (MCheM) [11] | LC-MS/MS data + functional group reactivity | Online derivatization (e.g., with AQC, L-cysteine) predicts functional groups to filter CSI:FingerID results. | Improved Top-1 annotation for 15-49% of test molecules; guided novel NP discovery [11]. |

4. Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Taxonomy-Focused (^{13})C NMR Database for Dereplication

- Objective: To create a custom database of predicted (^{13})C NMR spectra for all NPs reported from a specific taxon.

- Materials: LOTUS database access; ACD/Labs CNMR Predictor and DB software (or alternative); Python environment with RDKit.

- Method:

- Taxon-Specific Structure Retrieval: Query the LOTUS database using the organism's scientific name (e.g., Brassica rapa) and download the resulting structures in SDF format [4].

- Structure Curation: Use Python scripts (e.g.,

uniqInChI.py) to remove duplicate structures. Correct common tautomeric misrepresentations (e.g., iminol to amide) using a tool liketautomer.py[4]. - Spectral Prediction: Import the curated SDF file into ACD/Labs CNMR Predictor. Batch-predict (^{13})C NMR chemical shifts for all structures using the built-in function. Export the combined structure-spectra data as a new, searchable database file (e.g.,

.NMRUDB) [4]. - Deployment: Use this custom database within the NMR prediction software's search module. Query it with experimental (^{13})C NMR shift lists from new isolates of the target taxon for rapid identification [4] [8].

Protocol 2: SERS-Based Hierarchical Chemical Taxonomy for Epimer Identification

- Objective: To differentiate and quantify structurally similar epimers (e.g., GlcCer vs. GalCer) without pure standards.

- Materials: Ag nanocube SERS substrate; 4-mercaptophenylboronic acid (4-MPBA); hydrophobic perfluorothiol-Ag concentrating substrate; Target epimers.

- Method:

- Selective Capture: Functionalize the Ag SERS substrate with 4-MPBA, which covalently binds to the 1,2-diol group on the epimers at their site of isomerism [10].

- Signal Amplification: Concentrate the formed epimer-MPBA adducts on a hydrophobic secondary substrate to enhance the SERS signal [10].

- Spectral Acquisition & Feature Engineering: Acquire SERS spectra for all target epimers. Extract specific features (peak position, intensity, width, skew) corresponding to five hierarchical structural categories: 1) presence of epimer, 2) monosaccharide vs. cerebroside, 3) ceramide saturation, 4) glucosyl vs. galactosyl, 5) carbon chain length [10].

- Machine Learning Classification: Train a cascading machine learning model (e.g., four Random Forest classifiers followed by SVM regressors) using the engineered spectral features. Each model level predicts one of the hierarchical structural categories [10].

- Prediction: Input the SERS spectrum of an unknown epimer. The hierarchical model sequentially predicts its structural attributes, ultimately reconstructing its full identity and enabling quantification [10].

5. Visualizing the Workflow and Hierarchical Logic

The following diagrams illustrate the integrated dereplication process and the logical flow of a hierarchical identification model.

Diagram 1: The Integrated Three-Pillar Dereplication Workflow (75 chars)

Diagram 2: Hierarchical ML Model for SERS Chemical Taxonomy (75 chars)

6. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Item / Reagent | Function in Dereplication | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database & Software | LOTUS Database | Provides the essential taxonomic-structural relationship data to build focused libraries. | [4] |

| ACD/Labs CNMR Predictor | Generates high-accuracy predicted (^{13})C NMR spectra for database creation and shift verification. | [4] [8] | |

| RDKit (Python) | Enables cheminformatic curation of structure files (deduplication, tautomer correction). | [4] | |

| SIRIUS Software | Performs molecular formula identification (via isotope pattern) and MS/MS fragmentation analysis. | [11] | |

| SERS Analysis | 4-Mercaptophenylboronic Acid (4-MPBA) | SERS probe that selectively captures diol-containing analytes, creating diagnostic adduct spectra. | [10] |

| Ag Nanocube Substrate | Provides high surface enhancement for Raman signal amplification. | [10] | |

| Functional Group Labeling | 6-Aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl Carbamate (AQC) | Online derivatization reagent that labels amine/phenol groups, revealing their presence via MS mass shift. | [11] |

| L-Cysteine | Online derivatization reagent that reacts with electrophilic groups (e.g., β-lactones), constraining possible structures. | [11] |

7. Conclusion: Synthesis and Future Directions

The triad of taxonomy, spectroscopy, and molecular structures forms an indispensable, synergistic framework for modern natural product dereplication. The field is evolving from simple library matching toward predictive and intelligence-driven workflows. The integration of machine learning with spectroscopic techniques (as seen in SERS taxonomy) [10] and the use of chemical reactivity to constrain structural space (as in MCheM) [11] represent the vanguard. These approaches increasingly handle the "unknown unknowns" by deducing structural features de novo, moving beyond the limitations of static libraries. Future advancements will likely involve deeper integration of genomic data (biosynthetic gene clusters) as a fourth informing pillar, further closing the loop between an organism's genetic potential and its expressed chemical identity. For researchers, mastering the interplay of the three pillars, and leveraging the tools and databases that embody them, is fundamental to achieving efficiency and discovery in natural product science.

The Historical Evolution and Rationale Behind the Pillars

The renaissance of natural products (NP) as a critical source for new drug leads has been fundamentally enabled by the development of efficient dereplication strategies [9]. Dereplication—the rapid identification of known compounds within complex biological extracts—prevents the costly and time-consuming re-isolation and re-elucidation of previously characterized molecules, thereby streamlining the discovery pipeline [4]. This field's evolution is anchored in three interconnected pillars: Taxonomic Classification, Advanced Spectroscopy, and Structural Databases. Together, these pillars form a cohesive framework that transforms raw chemical data into actionable biological knowledge [9]. The integration of these domains is not merely operational but conceptual, providing a robust taxonomy for NP research that enhances reproducibility, accelerates discovery, and bridges the gap between chemical analysis and therapeutic application [12].

This article delineates the historical evolution and scientific rationale of these three pillars, framing them within the broader thesis that a tripartite, integrated approach is indispensable for modern NP research. We provide a technical examination of core methodologies, supported by quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and specialized visualization, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in the search for novel bioactive entities.

Historical Evolution of the Dereplication Framework

The dereplication landscape has evolved from a labor-intensive, discipline-siloed process to an integrated, informatics-driven science. Historically, NP discovery relied on bioactivity-guided fractionation coupled with structure elucidation using classical spectroscopic methods, a process often leading to the "rediscovery" of common metabolites [9]. The first major shift began with the digitization of chemical data. Early databases were simple compilations of structures and sources, but the need for cross-referenced information soon became apparent [4].

The advent of hyphenated analytical techniques, such as Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), in the late 20th century provided the second catalyst for change. This allowed for the partial characterization of compounds directly in complex mixtures [9]. However, the true transformation commenced with the conceptual integration of biological context (taxonomy) with chemical and spectroscopic data. This recognized that the metabolic profile of an organism is a product of its evolutionary history, implying that related taxa are more likely to produce structurally related NPs [4]. This principle provided the logical basis for integrating taxonomy as a filtering and prioritization layer in dereplication.

Concurrently, the proliferation of public spectral libraries and the development of reliable in-silico spectral prediction tools for both MS and NMR data allowed researchers to compare experimental results against vast virtual libraries [9] [4]. The most recent evolutionary phase is characterized by the rise of collaborative, open-data platforms like the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS), which leverage crowd-sourced data and network algorithms to visualize chemical space and identify novel compounds [9]. This historical arc demonstrates a clear trajectory toward deeper integration of the three pillars: using taxonomy to define a search space, spectroscopy to generate chemical descriptors, and curated databases to map those descriptors to known or predicted structures.

The Three Pillars: Rationale, Function, and Synergy

The efficacy of modern dereplication is predicated on the strength and interdependence of three foundational pillars.

Pillar 1: Taxonomic Classification

Taxonomy provides the biological context for chemical discovery. The rationale is rooted in chemotaxonomy—the observation that evolutionary relationships correlate with biosynthetic pathways and secondary metabolite production [4]. By defining the biological source (e.g., species, genus, family), researchers can constrain the vast universe of possible chemical structures to a more manageable subset associated with that taxon and its relatives. This significantly reduces false positives during database searching. For instance, a novel antifungal compound from a Penicillium species is more likely structurally related to other fungal metabolites than to algal terpenes. Modern taxonomy-focused databases like LOTUS directly link organism classification to reported metabolites, enabling this targeted filtering [4].

Pillar 2: Analytical Spectroscopy

Spectroscopy provides the unambiguous chemical descriptors of the sample. Mass Spectrometry (MS), particularly high-resolution MS (HRMS), delivers exact molecular mass and formula, along with fragmentation patterns that serve as a "fingerprint" of molecular structure [9]. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, especially 13C NMR, offers complementary, information-rich data on the carbon skeleton and functional groups, with high predictability and low susceptibility to solvent effects, making it ideal for database matching [4]. The synergy between MS (high sensitivity, mixture analysis) and NMR (high structural resolution) is paramount for confident identification.

Pillar 3: Integrated Structural & Spectral Databases

Databases serve as the collective memory and reference standard of the field. They integrate and curate data from the first two pillars: chemical structures, taxonomic origins, and associated spectroscopic signatures (both experimental and predicted) [9]. The power of this pillar lies in its searchability and interconnectivity. A dereplication workflow queries the spectral and chromatographic data of an unknown against these databases to find matches. The integration of predicted data, such as in-silico 13C NMR shifts, dramatically expands the coverage of these databases beyond compounds with fully published experimental spectra [4].

Table 1: Key Dereplication Databases and Their Characteristics

| Database Name | Primary Data Type | Notable Feature | Taxonomic Focus | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOTUS | Structures, Taxonomy | Links ~700k NPs to organism taxonomy; open-source | Comprehensive | [4] |

| GNPS | MS/MS Spectra | Crowd-sourced spectral library; molecular networking | Comprehensive | [9] |

| COCONUT | Structures | Aggregated collection from multiple NP DBs | Comprehensive | [4] |

| KNApSAcK | Structures, Taxonomy | Links species, metabolites, and biological activities | Comprehensive | [4] |

The synergistic interaction of these pillars creates a logical funnel. Taxonomy narrows the search space, spectroscopy generates precise query data, and integrated databases enable the final matching or annotation. This tripartite system mirrors structured cognitive frameworks used in other scientific fields, such as the Triple Taxonomy Technique (TTT) in medical education, which segments learning into recall, interpretation, and problem-solving to optimize outcomes [12]. Similarly, dereplication uses taxonomy (context recall), spectroscopy (data interpretation), and database mining (identification problem-solving).

Quantitative Analysis of Integrated Workflow Efficacy

The impact of integrating the three pillars is quantifiable in terms of efficiency gains and accuracy improvements. A study on educational methodology using a Triple Taxonomy Technique (TTT)—a relevant analog for structured, multi-stage processes—demonstrated high effectiveness when a tri-level approach was employed [12].

Table 2: Effectiveness Assessment of a Structured Tri-Level Methodology (Analogous to Integrated Dereplication)

| Metric | Result | Implication for Dereplication Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Agreement on Method Effectiveness | 92.5% (474 of 512 participants) | Validates the user acceptance and perceived utility of a structured, multi-stage framework. |

| Neutral or Disagreeing Response | 7.5% (38 of 512 participants) | Highlights a minority where the method may not fit or requires optimization. |

| Primary Strengths Identified | Enhanced data interpretation, analysis, decision-making, and problem-solving. | Directly correlates to the dereplication goals of accurate spectral interpretation and confident identification. |

In a technical context, the creation of a taxonomy-focused 13C NMR database for Brassica rapa using the CNMR_Predict workflow illustrates efficiency. Starting from 121 unique structures sourced from the LOTUS database (Pillar 1 and 3), the automated prediction and database creation process (leveraging Pillar 2 data) enables rapid future dereplication of compounds from this taxon [4]. This eliminates the need for manual literature searching and data entry for each candidate structure.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating a Taxonomy-Focused NMR Database for Dereplication

This protocol, based on the CNMR_Predict workflow, details the construction of a specialized database for dereplicating compounds from a specific organism or taxon using predicted 13C NMR data [4].

Define Taxon & Source Structures:

- Identify the biological source of the extract (e.g., Brassica rapa subsp. rapa L.).

- Query the LOTUS database using the organism's scientific name as a keyword. Export all associated chemical structures in V3000 SDF file format (e.g.,

lotus_result.sdf).

Structure File Preprocessing:

- Convert Format: Use cheminformatics tools (e.g., RDKit, Open Babel) to convert the SDF file to V2000 format for broader software compatibility.

- Remove Duplicates: Execute a script (e.g.,

uniqInChI.py) to remove duplicate structures based on standardized InChI identifiers. - Standardize Tautomers: Apply a tautomer standardization script (e.g.,

tautomer.py) to convert non-standard representations (e.g., iminol forms of amides) to their more common tautomeric form to ensure accurate chemical shift prediction. - Fix Atomic Valence: Run a script (e.g.,

rdcharge.py) to reset non-standard valence notations on charged atoms to default values to prevent errors in prediction software.

Predict 13C NMR Chemical Shifts:

- Import the cleaned structure file (

processed_structures.sdf) into spectroscopic prediction software (e.g., ACD/Labs CNMR Predictor). - Configure the prediction parameters (solvent, NMR frequency). Batch-process all structures to generate predicted 13C NMR chemical shift lists for each compound.

- Import the cleaned structure file (

Build and Export Searchable Database:

- Compile the structures and their associated predicted NMR data into a dedicated database file (e.g., an ACD/Labs .NMRUDB file or a SQLite database).

- Structure the database to allow searching by chemical shift ranges, molecular formula, or substructure. Export a final, portable version for use in dereplication workflows.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Triple Taxonomy Technique (TTT) for Method Validation

Adapted from educational research, this protocol provides a framework for systematically validating and optimizing individual components of a dereplication pipeline by breaking down the evaluation into distinct cognitive levels [12].

Design a Validation Case Study:

- Case Stem: Create a realistic dereplication scenario (e.g., "Identify the major antifungal component in this Streptomyces extract given the following HR-MS and 1H NMR data...").

- Three-Level Question Design:

- Recall/Knowledge: Questions testing knowledge of database resources, taxonomic principles, or fundamental spectroscopic rules (e.g., "Which public database is best for searching MS/MS spectra of natural products?").

- Interpretation/Analysis: Questions requiring analysis of provided spectral data (e.g., "Interpret the key fragments in this MS/MS spectrum to propose a molecular substructure.").

- Problem-Solving/Application: Tasks requiring the integrated use of tools and data to reach a conclusion (e.g., "Using the provided links, query the GNPS and LOTUS platforms to propose an identity for Compound X and justify your answer.").

Execute the Validation Session:

- Present the case study to a group of researchers or students trained in dereplication.

- Allocate a fixed time (e.g., 20-30 minutes) for participants to work through the questions.

Provide Structured Feedback:

- Review answers by explicitly categorizing them according to the three levels.

- For each level, discuss correct approaches, common pitfalls, and optimal strategies (e.g., for the "Problem-Solving" level, demonstrate the exact database query sequence).

Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment:

- Collect anonymous feedback via a structured questionnaire (e.g., using a platform like Porsline or Google Forms) to assess the perceived effectiveness of the method and identify pain points in the workflow.

- Analyze the accuracy of answers at each taxonomic level to pinpoint specific areas (e.g., spectral interpretation vs. database navigation) that require improved training or tool development.

Diagram Title: Taxonomy-Focused NMR Database Creation Workflow

Diagram Title: Triple Taxonomy Technique for Method Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for Integrated Dereplication Research

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Example | Primary Function in Dereplication |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic & Structural Databases | LOTUS, GNPS, COCONUT, KNApSAcK | Provide the reference corpus of known compounds linked to biological sources and/or spectra for comparison [9] [4]. |

| Analytical Instrumentation | UPLC-HRMS/MS, High-Field NMR Spectrometer (e.g., 500+ MHz) | Generate high-quality, information-rich spectroscopic data (exact mass, MS^n fragments, 13C/1H NMR shifts) from crude or fractionated extracts [9]. |

| Spectral Prediction Software | ACD/Labs CNMR Predictor, MS Fragmenters (e.g., CFM-ID, SIRIUS) | Generate in-silico reference spectra for database expansion or for matching when experimental reference is unavailable [4]. |

| Cheminformatics & Scripting Tools | RDKit, Python/Anaconda, Open Babel | Enable automated processing of chemical structure files (SDF, SMILES), data wrangling, and custom workflow creation (e.g., CNMR_Predict scripts) [4]. |

| Data Analysis & Visualization Platforms | GNPS Molecular Networking, Cytoscape, R/Python for statistics | Facilitate the visualization of complex datasets, reveal clusters of related compounds in extracts, and enable statistical analysis of results [9]. |

The future of dereplication lies in the deeper artificial intelligence (AI)-driven integration of the three pillars. Machine learning models are being trained to directly predict bioactive compounds from a combination of taxonomic metadata and untargeted metabolomics data, effectively bypassing traditional stepwise identification [9]. Furthermore, the expansion of real-time, on-demand spectroscopic prediction coupled with blockchain-verified data provenance will enhance the reliability and speed of database searches [4]. The ongoing development of microcoil and cryoprobe NMR technology will continue to improve sensitivity, allowing the full NMR characterization of ever-smaller quantities of material directly from chromatographic peaks [9].

In conclusion, the historical evolution of natural product dereplication has solidified around three indispensable pillars: Taxonomic Classification, Analytical Spectroscopy, and Integrated Databases. Their rationale is proven: taxonomy provides biological context and filters chemical space, spectroscopy delivers precise analytical descriptors, and databases offer the collective knowledge base for matching. As demonstrated by quantitative assessments and structured protocols, the synergy between these pillars creates a workflow that is greater than the sum of its parts. For researchers and drug developers, mastering this integrated framework is no longer optional but fundamental to efficiently navigating the complex yet rewarding landscape of natural product discovery.

The discovery and development of novel bioactive compounds from nature are complicated by the immense chemical diversity and the frequent re-isolation of known entities. Dereplication, the rapid process of identifying known compounds within complex mixtures, has therefore become a critical first step in natural product (NP) research [7]. This process is fundamentally supported by three interconnected pillars: biological taxonomy, molecular structure elucidation, and spectroscopic analysis [7] [13]. Chemotaxonomy, which utilizes the chemical profile of an organism for classification, provides the essential biological context, narrowing the search space to compounds likely produced by taxonomically related species [14]. The definitive identification rests on elucidating the precise molecular structure, while spectroscopic and spectrometric techniques provide the unique spectral signatures that serve as fingerprints for comparison [7] [15]. This whitepaper explores these core terminologies and methodologies, framing them within the integrated workflow of modern NP dereplication, which is essential for efficient drug discovery.

Foundational Concepts and Terminologies

- Chemotaxonomy: A subdiscipline of systematics that uses the distribution and composition of secondary metabolites (e.g., alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids) to classify and identify organisms [14]. It operates on the principle that related organisms share biosynthetic pathways and thus chemical profiles.

- Spectral Signature: The characteristic pattern of electromagnetic radiation absorbed, emitted, or scattered by a specific material or molecule at various wavelengths [15]. In NP research, this most commonly refers to signatures from Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Mass Spectrometry (MS), Infrared (IR), and Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy.

- Dereplication: The process of efficiently screening crude extracts or partially purified fractions to determine if a constituent is a novel compound or one that has been previously reported, thereby avoiding redundant isolation and characterization efforts [7] [16].

- Secondary Metabolite: Organic compounds not directly involved in the normal growth, development, or reproduction of an organism but which often play roles in defense, competition, and species interaction. They are the primary source of bioactive NPs [14].

- Chemotype: Intraspecific variants of a plant species that differ quantitatively and/or qualitatively in their secondary metabolite profile due to genetic variation, often leading to differences in biological activity [16].

Table 1: Core Analytical Techniques in Dereplication and Chemotaxonomy

| Technique | Acronym | Key Output/Data | Primary Role in Dereplication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance | NMR | ¹H/¹³C chemical shifts, coupling constants, 2D correlation spectra | Definitive structural elucidation and fingerprint matching [7] [16]. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS / LC-MSⁿ | Molecular mass, fragment ion patterns, chromatographic retention time | Rapid annotation of molecular formulas and tentative identification via fragmentation libraries [7] [17]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry | GC-MS | Volatile compound profiles, mass spectra | Chemotaxonomic profiling of volatile metabolites (e.g., terpenes, essential oils) [17]. |

| High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography | HPTLC | Chromatographic fingerprint (Rf values, band colors) | Low-cost, high-throughput screening for chemotype variation and sample comparison [16]. |

The Three Pillars of Dereplication: Taxonomy, Structures, and Spectroscopy

Pillar 1: Biological Taxonomy

Taxonomy provides the biological context essential for efficient dereplication. The evolutionary relationships between organisms imply shared biochemistry; thus, searching for known compounds from taxonomically related species significantly narrows the list of candidate structures [7]. Modern research integrates traditional morphology with molecular phylogenetics (using DNA barcodes like ITS, matK, and rbcL) to establish accurate taxonomic frameworks [17]. This integrated approach is crucial for resolving species complexes in genera like Kaempferia and Clusia, where morphological similarities obscure taxonomic boundaries [16] [17].

Pillar 2: Molecular Structure Representation and Databases

The unambiguous representation of molecular structures is fundamental. Structures are stored digitally as connection tables (e.g., in MOL or SDF file formats) or linear notations (SMILES, InChI) [7]. These digital representations populate Natural Product Databases (NP DBs), which are the essential tools for dereplication. Key databases include:

- LOTUS: A comprehensive, open-source database that rigorously links NP structures to the taxonomy of their source organisms [4].

- COCONUT: A collective database compiling structures from numerous public NP resources [7].

- KNApSAcK: A species-metabolite relationship database useful for chemotaxonomic searches [7].

- PubChem: A general chemical database containing a vast number of NP structures and associated biological data [7].

Pillar 3: Spectroscopic and Spectrometric Signatures

Spectroscopic data provides the experimental fingerprint for comparison. The trend is toward hyphenated techniques (e.g., LC-MSⁿ, LC-SPE-NMR) that generate multi-dimensional data streams for compounds directly from complex mixtures [18].

- NMR Spectroscopy: Offers the most detailed structural information. ¹³C NMR is particularly valuable for dereplication due to its wide spectral dispersion, sharp signals, and accurate chemical shift predictability [4]. Tools like MixONat software enable the dereplication of mixtures by comparing experimental ¹³C NMR shifts against predicted values in taxonomically focused databases [16].

- Mass Spectrometry: Provides high-sensitivity detection and molecular formula determination. Tandem MS (MSⁿ) and molecular networking (e.g., via the GNPS platform) allow for the visualization of related compounds within extracts based on shared fragmentation patterns [7].

- Integrated Spectral Signatures: The most robust identification comes from combining data types. For example, a molecular formula from HR-MS, combined with key ¹H and ¹³C NMR shifts, can often uniquely identify a known compound [7].

Table 2: Key Databases and Computational Tools for Dereplication

| Name | Type | Key Feature | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOTUS [4] | Structure-Taxonomy DB | Open-source, links compounds to source organisms via validated taxonomy. | Initial taxon-focused candidate list generation. |

| GNPS [7] | MSⁿ Data Platform | Crowdsourced mass spectral library and molecular networking. | MS-based annotation and discovery of related compounds. |

| CNMR_Predict [4] | Prediction Tool | Generates taxon-focused DBs with predicted ¹³C NMR shifts. | Creating custom dereplication libraries for specific study organisms. |

| MixONat [16] | Dereplication Software | Compares experimental ¹³C NMR mix data to predicted DBs. | Identifying components in partially purified fractions or crude mixtures. |

Integrated Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Taxon-Focused ¹³C NMR Dereplication Database

This protocol, exemplified by the CNMR_Predict tool, creates a custom database for targeted dereplication [4].

- Taxon Selection: Define the biological source (e.g., species Brassica rapa, family Clusiaceae).

- Structure Retrieval: Query the LOTUS database using the taxon name and download all associated compound structures in SDF format.

- Data Curation: Use Python/RDKit scripts to remove duplicate structures, correct tautomeric forms (e.g., convert iminols to amides), and standardize file formats.

- Spectral Prediction: Process the curated SDF file through commercial (e.g., ACD/Labs CNMR Predictor) or open-source ¹³C NMR prediction software to generate predicted chemical shifts for each compound.

- Database Deployment: The resulting database (e.g., a dedicated SDF or SQL DB) contains structures, source taxonomy, and predicted NMR shifts, ready for use with dereplication software like MixONat.

Protocol 2: HPTLC-Chemometrics-¹³C NMR for Chemotype Discovery

This integrated protocol identifies intraspecific chemotypes [16].

- Sample Preparation: Extract plant material (e.g., bark of Clusia spp.) and prepare semi-purified fractions of medium polarity.

- HPTLC Profiling: Run extracts/fractions on HPTLC plates. Develop and image plates under UV/Vis light to obtain chromatographic fingerprints.

- Chemometric Analysis: Digitize HPTLC band intensities. Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) to statistically identify outlier samples representing distinct chemotypes.

- ¹³C NMR Dereplication: Acquire ¹³C NMR spectra of the fractions from putative chemotypes. Input the experimental chemical shift lists into MixONat software, querying against a pre-built, taxonomically focused database (e.g., a Clusiaceae DB).

- Identification & Confirmation: Review top-scoring candidate compounds (score ≥ 0.70). Confirm identity by comparing full experimental and literature NMR data.

Protocol 3: Integrative Taxonomy via Morphology, DNA Barcoding, and Volatile Metabolomics

This protocol resolves classification of morphologically similar species [17].

- Morphological Characterization: Document qualitative and quantitative traits of fresh specimens (e.g., rhizome type, leaf shape, flower morphology).

- Molecular Phylogeny: Extract genomic DNA. Amplify and sequence standard DNA barcode regions (e.g., ITS, matK, rbcL, psbA-trnH). Reconstruct phylogenetic trees.

- Volatile Metabolomics: Use headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) coupled with GC-MS to capture the volatile profile of raw rhizome material without solvent extraction.

- Integrated Data Analysis: Perform multivariate analysis (e.g., Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures Discriminant Analysis - OPLS-DA) on GC-MS data to identify Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) markers that discriminate species. Correlate chemotypic clusters with clades in the phylogenetic tree.

- Marker Validation: Identify key discriminatory metabolites (e.g., specific sesquiterpenes) as validated chemotaxonomic markers for the species.

Diagram 1: The Integrated Dereplication Workflow (Width: 760px)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Protocols

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated NMR Solvents (e.g., CD₃OD, DMSO-d₆) | Provides the atomic lock signal and non-interfering environment for acquiring NMR spectra of pure compounds or mixtures. | Used in Protocol 2 for acquiring ¹³C NMR spectra of Clusia fractions [16]. |

| SPME Fiber Assemblies (e.g., DVB/CAR/PDMS) | Adsorbs volatile organic compounds from headspace of solid/liquid samples for direct thermal desorption in GC-MS. | Used in Protocol 3 for solvent-free volatile profiling of Kaempferia rhizomes [17]. |

| HPTLC Plates (Silica gel 60 F₂₅₄) | Stationary phase for high-resolution planar chromatography, enabling parallel analysis of multiple samples. | Used in Protocol 2 for fingerprinting Clusia extracts [16]. |

| DNA Barcoding Primers (e.g., ITS1/ITS4, matK primers) | Oligonucleotides designed to amplify specific genomic regions for phylogenetic analysis. | Used in Protocol 3 to amplify ITS, matK, rbcL regions from Kaempferia [17]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol) | High-purity mobile phase solvents for LC-MS to minimize background noise and ion suppression. | Used universally for preparing samples for LC-MSⁿ analysis in dereplication [7] [17]. |

| Taxon-Specific Natural Product Database (Custom SDF file) | Digital collection of structures and predicted spectra for a defined biological group, enabling focused searches. | The output of Protocol 1, used as input for dereplication in Protocol 2 [4] [16]. |

Diagram 2: Interrelation of the Three Pillars in Dereplication (Width: 760px)

Applications and Future Directions

The integrated application of these pillars drives modern bioprospecting. Research groups utilize this framework to discover leads for pharmaceuticals (e.g., anti-malarial alkaloids, anti-HIV agents), nutraceuticals, and cosmeceuticals from biodiverse resources [18]. The future of the field lies in further integration and automation:

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: For advanced pattern recognition in spectral data, predicting bioactive potential, and automating database curation [14].

- Real-Time Metabolomics: The development of faster, more sensitive analytical couplings for real-time, in-flow structural annotation.

- Global Collaborative Platforms: Expansion of open-access, curated databases like LOTUS and GNPS, which democratize data and accelerate discovery through crowdsourcing [7] [4].

- Standardization: Addressing the lack of standardized protocols for metabolite profiling and data reporting to improve reproducibility and data sharing across laboratories [14].

The convergence of chemotaxonomy, advanced spectroscopy, and robust bioinformatics within the three-pillar framework transforms natural product research from a slow, serial process into a rapid, informatics-driven discovery engine, crucial for the future of drug development.

Applied Strategies: Implementing Dereplication in Research Workflows

The re-emergence of natural products (NPs) as a cornerstone of drug discovery has been fueled by advanced dereplication strategies designed to rapidly identify known compounds early in the discovery pipeline [9]. Dereplication prevents the costly rediscovery of known molecules by cross-referencing analytical data against curated databases. This process stands upon three interdependent pillars: Taxonomy, Spectroscopy, and Structural Elucidation. Taxonomy, the science of biological classification, provides the essential evolutionary and ecological context that guides intelligent search strategies. By leveraging the principle that related organisms often produce chemically similar secondary metabolites, taxonomy acts as a powerful filter, dramatically narrowing the search space within complex spectral databases. This targeted approach, integrated with high-resolution spectroscopic data and structural annotation tools, forms the backbone of efficient NP research, accelerating the identification of novel bioactive scaffolds for therapeutic development [9].

Pillar I: Taxonomy – The Biological Context for Targeted Searching

2.1. Theoretical Foundation and Chemotaxonomic Principles Chemotaxonomy operates on the premise that biogenetic pathways for secondary metabolites are conserved within evolutionary lineages. This allows researchers to prioritize analytical efforts based on taxonomic provenance. For instance, searching for diterpenoids is more strategically focused in extracts from plants of the genus Salvia (Lamiaceae), while indole alkaloids are targeted in organisms from the Apocynaceae family. Modern dereplication workflows embed this taxonomic intelligence, using organism metadata as a primary search parameter to constrain database queries, thereby increasing both the speed and accuracy of compound identification [9].

2.2. Taxonomic Data Integration in Dereplication Workflows Effective integration requires structured, annotated databases. Key resources include the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) for organism taxonomy and specialized NP databases that link compounds to their biological sources. The first step in a taxonomy-driven protocol is the precise identification of the source organism, often verified by genetic barcoding. This taxonomic identifier then pre-filters spectral database searches, ensuring that MS or NMR data is compared first against compounds reported from related taxa.

Table 1: Key Taxonomic and Natural Product Databases for Dereplication

| Database Name | Primary Content | Role in Taxonomy-Driven Search | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility) | Authoritative taxonomic metadata and occurrence records | Provides standardized organism identification and phylogenetic context | Public |

| LotuS | Annotated database linking NPs to source organisms | Enables filtering of spectral searches by taxonomic clade | Academic/Commercial |

| CMAUP (Collection of Medicinal Plants and UniProt) | Integrated library of NPs from medicinal plants with target info | Allows target-based discovery within a taxonomic framework | Public |

| NPASS (Natural Product Activity and Species Source) | NP activities linked to species sources | Guides selection of source organisms based on desired bioactivity | Public |

The following diagram illustrates how taxonomic information directs the analytical workflow in natural product dereplication.

Diagram Title: Taxonomy-Guided Dereplication Workflow (100 chars)

Pillar II: Spectroscopy – The Analytical Engine for Compound Detection

3.1. Advanced Instrumentation for Dereplication The second pillar relies on high-resolution analytical technologies to generate robust chemical profiles. As of 2025, instrumentation continues to advance in sensitivity, speed, and hyphenation [19]. Key trends include the proliferation of miniaturized and field-portable devices (e.g., handheld NIR spectrometers) for in-situ analysis and the development of specialized laboratory systems like Quantum Cascade Laser (QCL)-based infrared microscopes for high-resolution spatial mapping of samples [19]. For dereplication, the core setup remains a hyphenated LC-MS/MS system, often coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and photodiode array (PDA) UV-Vis detection to provide multidimensional data (mass, fragmentation pattern, UV chromophore) in a single run [9].

3.2. Spectral Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing A standardized protocol is critical for generating reproducible, database-searchable data.

- Sample Preparation: Crude extract is dissolved in appropriate solvent and filtered.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Separation is performed on a reversed-phase C18 column with a water-acetonitrile gradient containing 0.1% formic acid. Data is acquired in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode on a HRMS instrument (e.g., Q-TOF or Orbitrap). The MS scans a mass range of m/z 100-1500, and the top N most intense ions are selected for fragmentation in each cycle.

- Data Processing: Raw files are converted to open formats (e.g., .mzML). Feature detection, alignment, and annotation are performed using software like MZmine 3 or GNPS, which output lists of m/z, retention time, and associated MS/MS spectra for downstream analysis [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Spectroscopic Techniques for Dereplication

| Technique | Key Information Provided | Typical Role in Dereplication | 2025 Instrumentation Trends [19] |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR-LC-MS/MS | Molecular formula (from m/z), fragmentation pattern | Primary tool for initial annotation via molecular networking and database search | Increased sensitivity; integration with ion mobility for isomeric separation |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Carbon skeleton, functional groups, stereochemistry | Definitive structural confirmation and isomer discrimination | Cryoprobes for microgram-scale analysis; automated structure verification software |

| UV-Vis/PDA | Chromophore presence (e.g., conjugated systems) | Supports compound class prediction (e.g., flavonoids, carotenoids) | Integrated into LC systems; diode array detectors with enhanced resolution |

| FT-IR & Microspectroscopy | Functional group fingerprint | Rapid characterization of bulk material or microscopic samples | QCL-based imaging (e.g., Bruker LUMOS II) for fast, high-contrast chemical mapping [19] |

Pillar III: Structural Elucidation – From Spectral Hit to Confirmed Identity

4.1. Database Searching and Molecular Networking The third pillar translates spectral data into chemical structures. The primary method involves searching acquired MS/MS spectra against reference spectral libraries such as GNPS, MassBank, or commercial databases. A taxonomy-driven approach is applied here by weighting or filtering results based on the source organism's taxonomic family, significantly improving accuracy [9]. For novel or unannotated spectra, molecular networking (via GNPS) is indispensable. This technique clusters MS/MS spectra by similarity, visualizing the chemical space of a sample and allowing analog-based annotation within a taxonomic context—where known compounds in a cluster can guide the identification of unknowns from the same organism.

4.2. Affinity Selection Mass Spectrometry (AS-MS) for Target-Guided Discovery Beyond passive dereplication, AS-MS represents a powerful target-oriented strategy for structural discovery within complex NP mixtures [20]. This label-free, biophysical method directly identifies ligands that bind to a purified protein target.

- Experimental Protocol for Ultrafiltration-Based AS-MS [20]:

- Incubation: A target protein (e.g., an enzyme) at low µM concentration is incubated with a crude natural extract or fraction library.

- Separation: The mixture is transferred to an ultrafiltration device (MWCO 10-30 kDa). Centrifugation retains the protein-ligand complexes while unbound compounds pass through.

- Washing: The retentate is washed with buffer to remove non-specifically bound molecules.

- Dissociation: Ligands are dissociated from the target using a denaturing solvent (e.g., 50% MeOH with 1% formic acid).

- Analysis: The eluent containing putative ligands is analyzed by LC-HRMS/MS. Compounds enriched in the experimental sample versus a target-free control are identified as binders.

- Annotation: The MS data of binders are processed through standard dereplication pipelines (Pillar II & III) for structural identification.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials for AS-MS Dereplication

| Item | Function in Experiment | Typical Specification / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Target Protein | Biological receptor for ligand binding. | Soluble, active protein (>90% purity); e.g., kinase, protease, 5-LOX [20]. |

| Ultrafiltration Unit | Physically separates protein-ligand complexes from unbound mixture. | Centrifugal filter, 10-30 kDa molecular weight cut-off (MWCO). |

| Binding/Wash Buffer | Maintains native protein conformation and specific binding interactions. | Typically pH 7.4 phosphate or Tris buffer, may include salts (NaCl) and stabilizers (DTT). |

| Dissociation Solvent | Denatures protein and disrupts non-covalent bonds to release ligands. | Methanol or Acetonitrile (40-60%) with 0.1-1% volatile acid (formic, acetic). |

| LC-HRMS/MS System | Separates, detects, and fragments the released ligands for identification. | Q-TOF or Orbitrap mass spectrometer coupled to UHPLC system. |

| Bioinformatic Software | Processes MS data, calculates enrichment ratios, and annotates structures. | GNPS for molecular networking; MZmine for feature finding; SIRIUS for formula prediction. |

Integrated Taxonomy-Driven Workflow: A Case Study

An integrated approach demonstrates the synergy of the three pillars. Consider the search for 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) inhibitors from the fungus Inonotus obliquus.

- Taxonomy (Pillar I): The organism is authoritatively identified. Literature and database mining reveal that Inonotus (Hymenochaetaceae) fungi are known producers of triterpenoids and phenolics with anti-inflammatory activity.

- Spectroscopy & Target Screening (Pillar II): A crude extract is prepared and screened using an ultrafiltration AS-MS assay with 5-LOX protein [20]. The ligand-protein mixture is processed, and putative binders are eluted and analyzed via LC-HRMS/MS, yielding accurate mass and MS/MS data for enriched features.

- Structural Elucidation (Pillar III): The HRMS data for a putative ligand (m/z 455.3523 [M+H]+) is first queried against NP databases filtered for Basidiomycota fungi. A molecular network is constructed, placing the unknown feature in a cluster with known triterpenoids. MS/MS fragmentation matches suggest a lanostane-type triterpenoid. This taxonomy-informed, spectroscopy-guided annotation is ultimately confirmed by isolation and NMR, identifying the compound as lanosterol, a known 5-LOX binder [20].

The relationship between the three pillars and the final research goal is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram Title: Interdependence of the Three Dereplication Pillars (99 chars)

Taxonomy-driven dereplication represents a paradigm of efficient natural product research, where biological intelligence systematically guides analytical and computational efforts. The integration of the three pillars—leveraging taxonomic context, cutting-edge spectroscopy, and robust structural annotation—creates a powerful feedback loop. Annotated compounds refine chemotaxonomic models, which in turn improve future search strategies.

The field is advancing toward fully automated, AI-integrated platforms. Future developments will likely include:

- Deep Learning-Enhanced Prediction: AI models trained on taxonomic and spectral data to predict novel compound classes directly from genomic or crude spectral data.

- Real-Time, Field-Deployable Systems: Combining portable DNA sequencers for on-site taxonomic identification with handheld MS-NMR devices for instant chemical profiling.

- Blockchain for Data Provenance: Ensuring immutable recording of taxonomic source data, promoting reproducibility and ethical sourcing in NP discovery.

By continuing to deepen the integration of taxonomy, spectroscopy, and structural elucidation, researchers can further streamline the path from complex natural extracts to novel therapeutic candidates, securing the vital role of natural products in the future of drug discovery.

The search for novel bioactive compounds from nature has undergone a paradigm shift, moving from serendipitous discovery to a systematic, data-driven scientific discipline. At the heart of this transformation lies dereplication—the rapid identification of known compounds early in the discovery pipeline to avoid redundant isolation and focus resources on true novelty [9]. This critical process is built upon three interconnected analytical pillars: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, Mass Spectrometry (MS), and Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy. When integrated within a taxonomy-aware framework, these techniques form a powerful triumvirate for elucidating the structures of natural products (NPs) [4] [9].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the acquisition, analysis, and integrated interpretation of data from these core spectroscopic techniques. Framed within the context of natural product dereplication taxonomy, we detail contemporary methodologies, from experimental protocols to advanced data fusion strategies, equipping researchers with the knowledge to efficiently navigate the complex chemical space of biological extracts [21] [22].

Foundational Techniques: Principles and Data Acquisition

2.1 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy NMR spectroscopy provides unparalleled insight into the covalent structure and three-dimensional configuration of organic molecules. It exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei (e.g., ¹H, ¹³C), yielding spectra that inform on atom connectivity, functional groups, and stereochemistry. For dereplication, ¹³C NMR is particularly valuable due to its wide spectral dispersion, minimal signal overlap, and predictable chemical shifts, allowing for direct database matching [4]. Modern workflows often involve the creation of taxonomy-focused ¹³C NMR databases. A representative protocol involves querying a comprehensive resource like the LOTUS database using a taxonomic keyword, processing the resulting structures with cheminformatic tools (e.g., RDKit), and supplementing them with predicted ¹³C chemical shifts from software such as ACD/Labs CNMR Predictor to create a tailored search library [4].

2.2 Mass Spectrometry (MS) MS determines the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ionized molecules and their fragments, providing exact molecular weight and structural clues. It is the cornerstone of high-sensitivity analysis for complex mixtures. Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS) and especially tandem MS/MS are indispensable. The fragmentation patterns in MS/MS spectra are highly reproducible and characteristic of specific molecular substructures [21]. The advent of Molecular Networking (MN), pioneered by the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform, has revolutionized MS data analysis. MN visualizes the relationships between compounds in a sample based on spectral similarity, grouping structurally related molecules into "molecular families" and guiding targeted isolation [21].

2.3 Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy UV-Vis spectroscopy measures the absorption of light by chromophores (e.g., conjugated π-systems, carbonyl groups). While providing less specific structural information than NMR or MS, it offers rapid, non-destructive quantification and is highly sensitive to compound classes. In hyphenated systems like LC-UV-Vis (or LC-PDA), it serves as a robust first-pass detector, generating UV spectra for each chromatographic peak that can be matched against libraries, aiding in the preliminary classification of compounds such as flavonoids, alkaloids, or polyphenols [19] [9].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Spectroscopic Techniques in Dereplication

| Technique | Key Information Obtained | Primary Role in Dereplication | Typical Sample Requirement | Key Strength | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR | Atomic connectivity, functional groups, stereochemistry, quantification. | Definitive structural elucidation and verification; ¹³C NMR database matching. | ~0.1 - 10 mg (for ¹H). | Non-destructive; provides complete structural details; excellent for quantification. | Lower sensitivity; requires relatively pure compound or advanced mixture analysis methods. |

| MS / MS-MS | Exact mass, molecular formula, fragmentation patterns, isotopic signatures. | High-throughput profiling of mixtures; molecular formula assignment; MN for compound families. | pg - ng (highly sensitive). | Extremely high sensitivity; works directly with complex mixtures; ideal for hyphenation with LC. | Destructive; ionization efficiency varies; limited direct stereochemical information. |

| UV-Vis | Chromophore presence, conjugation, concentration (via Beer-Lambert Law). | Rapid compound class screening; online detection in LC; quantification of known chromophores. | µg - mg. | Fast, simple, and inexpensive; excellent for quantification. | Low structural specificity; requires a chromophore; spectra often broad and overlapping. |

Integrated Analytical Workflows and Data Fusion

The greatest power in modern dereplication is realized not through individual techniques, but through their strategic integration. Hyphenated techniques like LC-MS/MS and LC-SPE-NMR combine separation power with rich spectroscopic detection. The subsequent fusion of data from multiple platforms creates a comprehensive analytical profile that is more than the sum of its parts [22].

3.1 Multi-Technique Dereplication Workflow A robust, taxonomy-informed dereplication pipeline begins with crude extract analysis. LC-MS/MS provides a metabolic fingerprint, which is processed via Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN) on the GNPS platform to visualize compound families and annotate known structures using spectral library matches [21]. Concurrently, LC-UV analysis offers preliminary compound class assignments. Bioactive or novel clusters identified via MN guide the targeted isolation of fractions. These fractions are then subjected to high-resolution ¹H and ¹³C NMR. The NMR data is queried against a taxonomy-focused database (e.g., created via the CNMR_Predict method for ¹³C shifts) [4]. A conclusive identification is achieved when evidence from all techniques—MS/MS fragmentation, UV chromophore, and NMR chemical shifts—converges on a single structure consistent with the known metabolites of the source organism's taxonomic group.

Taxonomy-Aware Dereplication Workflow

3.2 Data Fusion Strategies for NMR and MS Formal Data Fusion (DF) strategies systematically combine the complementary datasets from NMR and MS to build more robust and informative models [22]. These are categorized by the level of data integration:

- Low-Level DF: Direct concatenation of pre-processed raw data or feature tables (e.g., NMR chemical shift bins with MS m/z intensities). This retains maximum information but requires careful scaling to balance the contributions of each technique [22].

- Mid-Level DF: Integration of features extracted from each dataset separately (e.g., PCA scores from NMR and MS data). This reduces dimensionality before fusion, mitigating the "curse of dimensionality" [22].

- High-Level DF: Combination of final model outputs or decisions (e.g., classification results from independent NMR- and MS-based models). This offers flexibility and robustness, as each platform is modeled according to its own optimal parameters [22].

Data Fusion Strategies for NMR-MS Integration

Table 2: Essential Databases and Spectral Libraries for Dereplication

| Resource Name | Type | Key Content / Function | Primary Technique | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOTUS Initiative | Structural & Taxonomic DB | Curated relationships between NPs and their biological source organisms [4]. | All (Taxonomic filter) | Public Web Interface |

| GNPS / MassIVE | Spectral Library & Tools | Massive public repository of MS/MS spectra; platform for Molecular Networking and analysis [21]. | MS/MS | Public |

| CNMR_Predict Workflow | Predictive Tool & DB | Creates taxon-specific databases with predicted ¹³C NMR shifts from LOTUS structures [4]. | 13C NMR | Scripts Available |

| SciFinder-n | Comprehensive DB | Chemical Abstracts; extensive search for literature and experimental spectra [23]. | NMR, MS, IR | Subscription |

| Reaxys | Comprehensive DB | Chemical data, reactions, and properties from Beilstein/Gmelin [23]. | NMR, MS | Subscription |

| SDBS | Spectral DB | Curated IR, MS, Raman, and NMR spectra [23]. | NMR, MS | Public |

| NIST WebBook | Spectral DB | IR, MS, and UV-Vis spectra for a wide range of compounds [23]. | MS, UV-Vis | Public |

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item / Solution | Function in Experiment | Key Technical Note |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated NMR Solvents (e.g., CD3OD, DMSO-d6) | Provides a stable, deuterium lock signal for the NMR spectrometer and minimizes interfering proton signals from the solvent. | Choice affects compound solubility and can induce chemical shift variations. Must be of high isotopic purity (>99.8% D). |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents (Water, Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Used for mobile phase preparation and sample dilution. Minimizes background ions and noise, ensuring high signal-to-noise in MS detection. | Low UV cutoff is also critical for LC-UV detection. Must be free of polymeric and ionic contaminants. |

| Formic Acid / Ammonium Acetate | Common volatile additives for LC-MS mobile phases. Acidifiers (formic acid) promote positive ionization; buffers (ammonium acetate) aid in separation and negative ionization. | Concentration is critical (typically 0.1%). Non-volatile buffers (e.g., phosphate) are incompatible with MS. |

| Silica & C18 Stationary Phases | For preparative and solid-phase extraction (SPE) purification. Isolates individual compounds or enriched fractions for pure NMR analysis. | Particle size and pore geometry dictate resolution and loading capacity. |

| NMR Reference Standards (e.g., TMS, DSS) | Provides a chemical shift reference point (0 ppm) for calibrating NMR spectra, ensuring data is comparable across instruments and labs. | Added in minute quantities. DSS is preferred for aqueous samples. |

| Ultrapure Water System (e.g., Milli-Q) | Produces Type I water for all aqueous solutions, buffers, and mobile phases. Eliminates interferents from ions, organics, and particles. | Essential for baseline stability in LC-UV and to avoid ion suppression in MS [19]. |