The Evolving Landscape of Natural Product Databases: A 2025 Review of Trends, Applications, and Challenges in Drug Discovery

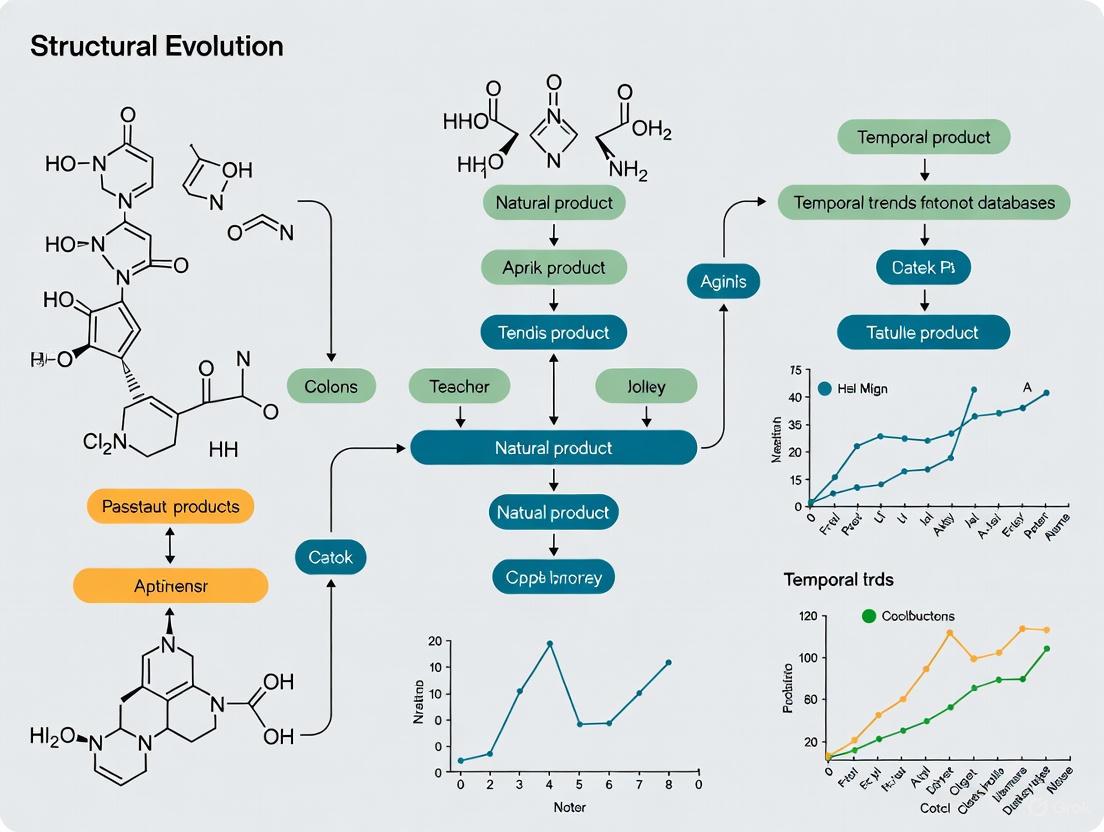

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the structural evolution and temporal trends in natural product (NP) databases from 2000 to the present.

The Evolving Landscape of Natural Product Databases: A 2025 Review of Trends, Applications, and Challenges in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the structural evolution and temporal trends in natural product (NP) databases from 2000 to the present. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational growth of over 120 NP resources, detailing the shift from commercial monopolies to open-access initiatives like COCONUT, which now aggregates over 400,000 non-redundant compounds. The review further examines the methodological applications of these databases in virtual screening, knowledge graph construction, and molecular generation. It addresses critical troubleshooting aspects related to data quality, stereochemistry, and accessibility, and offers a comparative validation of major commercial and public databases. By synthesizing two decades of progress, this article serves as an essential guide for leveraging NP databases to accelerate modern, computation-enabled drug discovery.

From Proliferation to Curation: The Historical Expansion of Natural Product Databases

The field of natural products (NPs) research has witnessed an unprecedented data revolution over the past two decades. In 2000, researchers had access to approximately 20 dedicated NP databases; by 2020, this number had exploded to over 120 different databases and collections [1]. This remarkable growth, representing a six-fold increase, reflects both the continuing scientific interest in NPs and the broader data explosion across the life sciences. Natural products, defined as chemicals produced by living organisms excluding primary metabolites, have been the cornerstone of drug discovery for centuries. Between 1981 and 2019, 68% of approved small-molecule drugs were directly or indirectly derived from natural products [2].

This proliferation of resources, however, has created significant challenges alongside opportunities. Researchers now face a fragmented landscape of specialized databases with varying accessibility, curation standards, and focuses. The lack of a centralized community resource for NPs, analogous to UniProt for proteins or NCBI Taxonomy for organisms, has led to duplication of efforts and accessibility issues [1]. This comprehensive analysis tracks the evolution of NP databases from 2000 to the present, quantifying their expansion, classifying their diversity, and providing researchers with methodological frameworks for navigating this complex ecosystem. Understanding this structural evolution is crucial for advancing NP research in drug discovery, cosmetic development, and agricultural applications.

Quantitative Analysis: Mapping Two Decades of Database Expansion

The Current Landscape of NP Databases

Table 1: Classification and Accessibility of Natural Products Databases (as of 2020)

| Database Category | Total Number | Open Access | Commercial | No Longer Accessible |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All NP Databases | 123 | 50 | - | 25 |

| Generalistic | - | 16 | - | - |

| Thematic | - | 18 | - | - |

| Metabolite | - | 7 | - | - |

| Spectral | - | 5 | - | - |

| Industrial Catalogs | - | 4 | - | - |

The comprehensive review of NP resources published in the Journal of Cheminformatics in 2020 revealed a total of 123 distinct NP databases and collections cited in scientific literature since 2000 [1]. This represents the most complete census of NP databases available. However, this quantitative expansion has not translated into uniform accessibility. Of these 123 resources, only 98 remained accessible in some form as of 2020, with a mere 50 offering open access to their data. This signifies a dramatic data loss rate of approximately 20% over two decades, highlighting the sustainability challenges in this rapidly evolving field [1].

Among the open-access databases, researchers can leverage resources across several categories. Generalistic databases (16 open resources) provide broad coverage without specific taxonomic or geographic focus. Thematic databases (18 open resources) concentrate on specific areas such as traditional medicine, particular geographic regions, or specific taxonomic groups. Additional specialized categories include metabolite databases (7 open resources) that include both primary and secondary metabolites, spectral databases (5 open resources) focused on NMR and mass spectrometry data for dereplication, and industrial catalogs (4 open resources) from companies that synthesize or isolate NPs for sale [1].

Table 2: Content Comparison of Major Natural Products Databases

| Database Name | Type | Number of Compounds | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COCONUT | Generalistic | >400,000 | Largest open collection; non-redundant | Open |

| Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP) | Commercial | ~300,000 | Most complete; best-curated | $6,600/year |

| SciFinder | Commercial | >300,000 | Largest curated collection overall | >$40,000/year |

| Reaxys | Commercial | ~200,000 | Includes substances, reactions, documents | Commercial |

| MarinLit | Commercial | - | Marine NPs; highly curated since 1970s | Commercial |

| AntiBase | Commercial | ~40,000 | NPs from microorganisms & higher fungi | Commercial |

The content analysis of available NP databases reveals significant variation in scale and specialization. The COlleCtion of Open NatUral prodUcts (COCONUT) represents the largest open-access resource, containing structures and sparse annotations for over 400,000 non-redundant NPs [1]. This collection was compiled from multiple open-access resources and made available on Zenodo to ensure preservation and accessibility. In the commercial domain, the Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP) is widely considered the most complete and best-curated resource, containing approximately 300,000 compounds with an annual subscription cost of around $6,600 [1]. Even more extensive is SciFinder from the Chemical Abstracts Service, which likely represents the largest curated collection of NPs overall with over 300,000 entries, though with substantially higher access costs exceeding $40,000 annually [1].

The structural diversity contained within these databases is remarkable. Comparative analyses indicate that NPs occupy a more diverse chemical space than synthetic compounds, with higher structural complexity and uniqueness [2]. This diversity stems from millions of years of evolutionary selection and explains why NPs remain invaluable for drug discovery, offering privileged scaffolds that interact with biological targets through novel modes of action.

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols for Database Analysis

Bibliometric Analysis of Research Trends

The methodological approach for analyzing trends in NP database development and utilization has been significantly advanced through bibliometric analysis. This quantitative method employs tools like CiteSpace and VOSviewer to map collaborative networks, analyze research hotspot evolution, and identify emerging frontiers [3]. The standard protocol involves:

Data Retrieval: Querying scientific literature databases like Web of Science Core Collection using Boolean logic to construct comprehensive search strategies. A typical query includes terms related to natural products combined with database, cheminformatics, or virtual screening terminology [3].

Data Screening: Applying strict inclusion/exclusion criteria to filter results to relevant publications, typically research articles and review articles in English. This process usually reduces the initial result set by 5-10% after removing duplicates and irrelevant document types [3].

Network Construction: Creating collaboration networks among countries, institutions, and authors where nodes represent research entities and connecting lines indicate relationship strength. Nodes with centrality values exceeding 0.1 are considered pivotal points within the research domain [3].

Trend Analysis: Performing co-citation analysis, keyword co-occurrence mapping, and burst detection to identify developmental trajectories and emerging concepts. Temporal visualization reveals how research focus has shifted from phenomenological description toward mechanistic investigation and clinical translation [3].

This methodology was successfully applied to the hypertension-gut microbiota field, analyzing 2,827 qualified publications and revealing three distinct evolutionary phases: slow accumulation (2000-2013), accelerated growth (2014-2019), and high-level stabilization (2020-2025) [3]. Similar approaches can be adapted specifically for analyzing NP database development trends.

Chemoinformatic Analysis of Structural Data

For analyzing the structural content of NP databases, chemoinformatic protocols have been developed to enable systematic comparisons:

Data Standardization: Converting structural representations from various formats (SMILES, SDF, InChI) into standardized, comparable representations. This process includes removing duplicates and standardizing stereochemical representations [1].

Descriptor Calculation: Computing key molecular descriptors including physicochemical properties (molecular weight, logP, polar surface area), structural features (ring systems, functional groups), and complexity metrics [2].

Scaffold Analysis: Decomposing molecules into their core structural frameworks using algorithms such as Bemis-Murcko scaffolding, then analyzing scaffold diversity and complexity across databases [2].

Chemical Space Mapping: Using dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and visualization methods like Tree MAP (TMAP) to compare and contrast the chemical space covered by different NP databases [2].

A recent time-dependent chemoinformatic analysis compared NPs with synthetic compounds, revealing that NPs have become larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic over time, exhibiting increased structural diversity and uniqueness [2]. This analysis of 186,210 NPs and an equal number of synthetic compounds, grouped into 37 chronological cohorts, provides a template for similar temporal analyses of NP database content evolution.

Database Analysis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated methodological approach combining bibliometric and chemoinformatic analyses for tracking NP database evolution.

Research Reagent Solutions for NP Database Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Natural Products Database Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CiteSpace | Software | Bibliometric analysis & visualization | Mapping research trends, collaboration networks |

| VOSviewer | Software | Network visualization & clustering | Creating co-authorship, co-citation networks |

| COCONUT | Database | Largest open NP collection (>400,000 compounds) | Virtual screening, chemical space analysis |

| Dictionary of Natural Products | Database | Comprehensive commercial NP resource | Reference data, structural verification |

| SciFinder | Database | Largest curated chemical database | Extensive literature and compound searching |

| RDKit | Software | Cheminformatics toolkit | Structural analysis, descriptor calculation |

| CDK | Software | Cheminformatics libraries | Molecular fingerprinting, property calculation |

| KNIME | Platform | Data analytics workflow platform | Building automated analysis pipelines |

The effective utilization of NP databases requires a sophisticated toolkit of research reagents and analytical resources. For bibliometric analysis, CiteSpace and VOSviewer have emerged as essential software tools, enabling quantitative mapping of scientific literature and collaboration patterns in the NP field [3]. These tools specialize in different aspects of analysis—CiteSpace excels in temporal evolution analysis and burst detection, while VOSviewer specializes in collaboration network construction and co-occurrence clustering [3].

For structural analysis of NP database content, cheminformatics toolkits like RDKit and the Chemistry Development Kit (CDK) provide essential functions for calculating molecular descriptors, generating chemical fingerprints, and analyzing structural diversity. These open-source tools can be integrated into workflow platforms like KNIME to create reproducible analysis pipelines for comparing NP databases [2] [1].

The database resources themselves form the core of the NP research toolkit. For researchers without access to commercial resources, the COCONUT database provides an unprecedented collection of over 400,000 open-access NPs, making it the most comprehensive free resource available [1]. For institutions with appropriate budgets, commercial resources like the Dictionary of Natural Products and SciFinder offer superior curation, more extensive metadata, and broader coverage of the NP literature [1].

Future Perspectives: Challenges and Emerging Directions

Despite the remarkable expansion of NP databases, significant challenges remain in the field. The fragmentation of data across numerous resources with different structures, annotation standards, and accessibility creates barriers to comprehensive analysis [1]. The loss of approximately 20% of NP databases over the past two decades highlights sustainability issues and the risk of valuable data becoming inaccessible to the research community [1]. Additionally, inconsistent stereochemical representation remains a problem, with almost 12% of collected molecules in open databases lacking stereochemistry information despite having stereocenters [1].

Future developments in the field are likely to focus on several key areas. Integration initiatives that combine data from multiple sources into unified, standardized repositories will be essential for overcoming fragmentation. The FAIR Guiding Principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) provide a framework for improving data management and stewardship in the NP field [1]. There is also growing interest in artificial intelligence and machine learning applications for predicting NP bioactivity, optimizing virtual screening, and identifying novel structural patterns across large database collections [3].

The continued discovery of NPs with unique structural features suggests that database growth will continue. Recent analyses indicate that newly discovered NPs tend to be larger and more complex than their early counterparts, with more ring systems and increased structural diversity [2]. This expanding chemical space ensures that NP databases will remain essential resources for drug discovery and chemical biology, providing inspiration for new therapeutic agents and biological probes.

The dramatic expansion of natural products databases from approximately 20 resources in 2000 to over 120 today represents a fundamental transformation in how researchers access and utilize NP information. This database boom has created unprecedented opportunities for drug discovery, chemical biology, and materials science, while also presenting significant challenges in data integration, standardization, and preservation. The structural evolution of NP databases reflects broader trends in scientific data management, with increasing emphasis on open access, interoperability, and computational accessibility.

For researchers navigating this complex landscape, methodological approaches combining bibliometric analysis and chemoinformatic techniques provide powerful tools for tracking field evolution and analyzing database content. Essential resources like the COCONUT database offer comprehensive open-access NP collections, while commercial resources like the Dictionary of Natural Products provide expertly curated data for those with appropriate access. As the field continues to evolve, emphasis on FAIR data principles, sustainable database maintenance, and integration of artificial intelligence methodologies will be crucial for maximizing the scientific value of natural products information.

The continued growth and specialization of NP databases ensures that these resources will remain indispensable for uncovering the chemical diversity evolved in nature and harnessing it for addressing human health challenges, agricultural needs, and material science applications. The structural knowledge contained within these databases represents a foundational resource for the next generation of natural product discovery and development.

The structural evolution of natural product databases is intrinsically linked to the frameworks governing how scientific data is shared, accessed, and utilized. In modern research, particularly in life sciences and drug development, two parallel movements are shaping this landscape: the push for Open Data and the implementation of FAIR Data Principles. While often conflated, these frameworks represent distinct philosophies with significant implications for the pace and reproducibility of scientific discovery.

The analysis of natural products (NPs) has historically been a cornerstone of drug development, contributing to over 60% of marketed small-molecule drugs [4]. However, the advancement of this field faces a major challenge due to the combinatorial expansion of NPs' configurational space and their complex 3D structures [4]. Concurrently, the volume and complexity of data generated in modern research have necessitated more robust data management strategies. This article analyzes the trends in data accessibility by objectively comparing the principles of Open and FAIR data, placing this comparison within the broader thesis of structural evolution and temporal trends in natural product databases research. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this interplay is crucial for navigating the future of data-driven discovery.

Defining the Frameworks: Open Data and the FAIR Principles

What is Open Data?

Open Data is characterized by its free accessibility and usability. It is a movement rooted in ideals of transparency and collaboration, aiming to make data available to everyone without restrictions for use, dissemination, and further development [5] [6]. The core principles of Open Data include:

- Availability and Access: The data must be freely accessible to all, preferably by downloading over the internet without paywalls or complex permissions [7].

- Reuse and Redistribution: There are no legal or technical restrictions on how the data can be utilized. The data must be provided under terms that permit reuse and redistribution, including the intermixing with other datasets [7] [6].

- Universal Participation: The data should be available to everyone to use and republish without restrictions, promoting innovation and societal benefit [7].

What are the FAIR Data Principles?

FAIR is a set of guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship designed to optimize data reuse. Their aim is to enhance the interoperability and reusability of digital assets, addressing the increasing volume and complexity of data in modern research [7] [8]. The acronym FAIR stands for:

- Findable: Data and metadata should be easy to locate by both humans and computer systems. This involves assigning unique and persistent identifiers (e.g., DOIs) and providing rich metadata that is registered in a searchable resource [7] [6].

- Accessible: Data should be retrievable by its identifier using a standardized, open, and universally implementable protocol. It is important to note that the "A" in FAIR means "accessible under well-defined conditions," which allows for data protection when necessary and does not demand unrestricted access [7] [5].

- Interoperable: Data should be structured in a way that allows for seamless integration with other datasets and applications. This involves using shared languages, standardized vocabularies, and qualified references to other metadata [7] [6].

- Reusable: Data should be well-described to allow for replication and combination in different settings. This includes having clear usage licenses, detailed provenance information, and meeting domain-relevant community standards [7] [6].

Comparative Analysis: Open Data vs. FAIR Data

While Open Data and FAIR Data share the common goal of making data more available, they differ in several key aspects, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Open Data and FAIR Data

| Aspect | Open Data | FAIR Data |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Promotes unrestricted sharing and transparency [7] | Ensures data is machine-readable and reusable [7] |

| Accessibility | Always open and freely available to all [7] | Can be open or restricted based on use case (e.g., privacy, IP) [7] [5] |

| Primary Focus | Human usability and redistribution [6] | Both human and computational usability, with a strong emphasis on machine-actionability [7] |

| Metadata & Documentation | Can be included but is not a strict requirement [7] | Rich metadata and clear documentation are fundamental requirements [7] [6] |

| Interoperability | Not a core requirement; data formats may vary [7] | A core principle; emphasizes standardized vocabularies and formats [7] |

| Typical Licensing | Utilizes open licenses like Creative Commons [7] | Varies—can include access restrictions and specific terms of use [7] |

A key distinction is that not all Open Data is FAIR, and not all FAIR data is Open [7] [5]. For instance, sensitive clinical trial data can be managed according to FAIR principles—making it findable and accessible under specific conditions to researchers—without being made fully open to the public, thus protecting patient privacy [7]. Conversely, a dataset might be freely available online (Open) but lack the structured metadata and persistent identifiers needed for a machine to process it automatically, rendering it not FAIR.

The Context of Natural Product Research and Structural Evolution

The concepts of Open and FAIR data are highly relevant to the field of natural product (NP) research, which is undergoing its own evolution. Chemoinformatic analyses reveal distinct temporal trends in the structural characteristics of NPs compared to synthetic compounds (SCs).

Temporal Trends in Natural Product and Synthetic Compound Structures

A time-dependent comparative study of over 186,000 NPs and 186,000 SCs has shown that the structural evolution of these two classes of compounds is diverging [2]. Key findings include:

- Molecular Size: Recently discovered NPs tend to be larger, with consistent increases in molecular weight, volume, and surface area. In contrast, the size of SCs has remained within a more limited range, likely constrained by synthetic technology and drug-like rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five [2].

- Ring Systems: NPs are becoming more complex, with a gradual increase in the number of rings, particularly non-aromatic rings and sugar rings (glycosylation). SCs, meanwhile, are characterized by a greater prevalence of aromatic rings, with stable five- and six-membered rings being dominant [2].

- Chemical Space and Biological Relevance: NPs exhibit increased structural diversity and uniqueness, occupying a chemical space that is less concentrated than that of SCs. While SCs possess broader synthetic pathway diversity, there is a noted decline in their biological relevance over time [2].

These trends underscore the critical importance of NPs as a source of novel structures for drug discovery. However, a significant bottleneck persists: over 20% of known NPs lack complete chiral configuration annotations, and only 1–2% have fully resolved crystal structures [4]. This highlights an acute need for advanced structural prediction and data management tools.

The Role of FAIR and Open Data in Advancing NP Research

The structural complexity and volume of NP data make FAIR principles particularly crucial.

- Enabling AI and Machine Learning: The interoperability of big data for machines is fundamental for applying technologies like large language models (LLMs) and neural networks to NP research [5]. For example, the NatGen deep learning framework achieves near-perfect accuracy in predicting the 3D structures of natural products [4]. Such tools rely on high-quality, well-structured, and accessible datasets for training and validation.

- Facilitating Collaboration and Reproducibility: In collaborative drug discovery projects, FAIR data principles facilitate data sharing while protecting sensitive information or intellectual property [7]. Making data both Open and FAIR enhances research reproducibility by making data available for validation studies, as seen with resources like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [7].

- Bridging Structural Gaps: The findings that SCs have not fully evolved in the direction of NPs suggest a missed opportunity for bio-inspired drug discovery [2]. Openly available and FAIR-compliant NP databases can serve as a foundation for designing new pseudo-natural products and synthetic compounds that capture the valuable biological relevance of NPs.

Experimental Methodologies in Data Trend Analysis

Methodology for Time-Dependent Structural Comparison

The comparative analysis of NPs and SCs relied on a comprehensive chemoinformatic approach [2].

- Data Curation: 186,210 NPs and 186,210 SCs were sourced from specialized databases, including the Dictionary of Natural Products and 12 synthetic compound databases.

- Temporal Grouping: Molecules were sorted in chronological order based on their CAS Registry Numbers and divided into 37 sequential groups of 5,000 molecules each.

- Descriptor Calculation: A total of 39 physicochemical properties were computed for each molecule to characterize molecular size, ring systems, and other structural features.

- Fragment and Scaffold Analysis: Bemis-Murcko scaffolds, ring assemblies, side chains, and RECAP fragments were generated and compared using multiple metrics to assess structural diversity and complexity over time.

- Chemical Space Visualization: The chemical space of NPs and SCs was characterized and compared using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Tree MAP (TMAP), and SAR Map.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Structural Trend Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| CAS Registry Numbers | Database Identifier | Used as a proxy for establishing the chronological order of compound discovery/synthesis [2]. |

| Dictionary of Natural Products | Commercial Database | A primary source for curated natural product structures and data [2]. |

| Bemis-Murcko Scaffolds | Computational Framework | Extracts the core molecular frameworks from structures to enable scaffold diversity analysis [2]. |

| RECAP Fragments | Computational Algorithm | Generates logical molecular fragments based on common chemical reactions; used for fragment-based comparison [2]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Statistical Method | Reduces the dimensionality of multivariate data (e.g., physicochemical properties) to visualize and compare chemical space [2]. |

Methodology for Assessing FAIR Data Compliance

Educational studies have developed and tested tools to evaluate the FAIRness of research data. One such study implemented a cross-sectional assessment within a postgraduate bioinformatics program [8].

- Tool Development: An 11-item questionnaire was developed based on existing tools like the ARDC FAIR Data Self-Assessment Tool. The questions were adapted to a Likert-type scale to measure the degree of adherence to each of the FAIR principles.

- Implementation: Students were trained in FAIR principles and data literacy. They were then instructed to implement Data Management Plans (DMPs) for their master's thesis projects, which included describing data systems, flow, roles, and methods for backup, storage, and archiving.

- Evaluation: The developed questionnaire was used to self-assess the FAIR status of the datasets used in the student projects. The questionnaire's internal consistency was statistically validated using Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega coefficients, confirming its reliability as an assessment tool [8].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and interplay between the Open and FAIR data principles, and their combined role in supporting scientific research.

The analysis reveals that the Open and FAIR data movements are not mutually exclusive but are complementary forces driving the future of scientific research. The structural evolution of natural products, marked by increasing complexity and a unique chemical space, presents both a challenge and an opportunity. Fully leveraging this resource requires data management strategies that prioritize not only openness for collaboration but also the computational usability ensured by the FAIR principles.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the implication is clear: a strategic integration of both frameworks is essential. Future efforts should focus on building and contributing to NP databases that are both open, to foster transparency and collaboration, and FAIR, to enable advanced computational analysis, AI-driven discovery, and the reproducible science that will accelerate the development of new therapeutic agents.

The systematic discovery and development of natural products (NPs) are intrinsically linked to the databases that catalog them. Foundational databases have evolved from static printed directories to dynamic, digitally-native platforms that leverage artificial intelligence (AI) and cheminformatics to dramatically expand the accessible chemical space. Framed within the structural evolution and temporal trends in natural product database research, this transition marks a paradigm shift from mere archival to predictive and generative discovery. These resources are indispensable for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, as they provide the critical data needed for dereplication (the early identification of known compounds to avoid rediscovery), bioactivity screening, and cheminformatics analysis [9]. This guide objectively compares the performance and methodologies of cornerstone databases—highlighting the established commercial platform SciFinder, the open-access COCONUT, and the impact of AI-driven expansions—thereby mapping the trajectory of how NP knowledge is curated, accessed, and utilized.

Database Profiles and Comparative Analysis

This section provides a detailed comparison of the featured databases, outlining their core characteristics, data sources, and typical use cases to help researchers select the appropriate tool for their projects.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Foundational Natural Product Databases

| Feature | SciFinder | COCONUT | AI-Generated NP-Like Libraries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provider / Origin | CAS (a division of the American Chemical Society) | Collection of Open Natural Products | Research Institutions (e.g., Scientific Data, 2023) |

| Primary Access Model | Commercial Subscription | Open Access / Free | Open Access |

| Data Source & Curation | Highly curated from scientific literature and patents; human-edited [10] | Publicly available sources; curated but broader scope [11] | Algorithmically generated via deep learning models (e.g., RNN/LSTM) trained on known NPs [11] |

| Key Content & Size | Comprehensive coverage of chemistry, including millions of substances and reactions; not exclusively for NPs. | Exclusively NPs; >400,000 unique compounds [11]. | 67 million NP-like molecules from one study—a 165-fold expansion of known NP space [11]. |

| Key Strengths | Authority, reliability, integration of reaction and patent data, advanced analytical and retrosynthesis tools [10] | Dedicated to open NP data, facilitates non-proprietary research | Unprecedented scale and novelty, designed for high-throughput in silico screening and inverse design [11] |

| Ideal Use Cases | Dereplication, patent analysis, literature reviews, synthetic route planning [9] [10] | Academic research, mining NP-specific chemical space, projects requiring open data | Exploring novel chemical scaffolds, initial virtual screening campaigns, training machine learning models |

Experimental Protocols for Database Utilization and Benchmarking

The value of a database is realized through its application in real-world research workflows. The following experimental protocols outline standard methodologies for leveraging these resources in NP discovery and for conducting performance comparisons.

Protocol 1: Dereplication and Metabolomics Workflow

Objective: To rapidly identify known compounds in a biological extract and prioritize novel ones for further investigation [9] [12].

Sample Preparation and Analysis:

- Prepare an ethyl acetate extract of the source material (e.g., microbial culture, plant tissue).

- Analyze the extract using Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to separate compounds and obtain fragmentation data.

Data Pre-processing:

- Convert raw LC-MS/MS data into open-source formats (e.g., .mzML) using tools like MSConvert.

- Use software like MZmine or XCMS for peak picking, alignment, and deisotoping to create a list of mass features and associated fragmentation spectra (MS/MS).

Database Querying and Molecular Networking:

- Submit the acquired MS/MS spectra to the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform.

- Simultaneously, search the experimental spectra against curated spectral libraries within GNPS, which often integrates data from sources like COCONUT.

- For precise mass matching, query the molecular formula or exact mass against structured databases like SciFinder or COCONUT to retrieve known compounds and their reported activities.

Dereplication and Prioritization:

- Compounds with high spectral similarity matches in databases are flagged as known and deprioritized.

- Unknown features or those with low similarity scores are considered putative novel compounds and prioritized for downstream isolation and structure elucidation [12].

Protocol 2: Performance Benchmarking of Database Content

Objective: To quantitatively compare the structural diversity, novelty, and "natural product-likeness" of different databases [11].

Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Download SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) strings of compounds from the databases to be compared (e.g., COCONUT vs. an AI-generated library).

- Standardize the structures using a cheminformatics toolkit (e.g., RDKit) according to a consistent protocol: neutralization, removal of salts and solvents, and generation of canonical SMILES.

Descriptor Calculation and Diversity Analysis:

- Calculate a set of key molecular descriptors (e.g., Molecular Weight, LogP, Topological Polar Surface Area, number of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, rotatable bonds) for all compounds in each dataset.

- Use dimensionality reduction techniques like t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) or Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to project the high-dimensional descriptor space into 2D or 3D plots. This visualizes the coverage and overlap of chemical space by the different databases [11].

Natural Product-Likeness Scoring:

- Calculate the NP Score for all compounds. This is a Bayesian measure that evaluates how closely a molecule's structure resembles known natural products based on atom-centered fragments [11].

- Compare the distribution of NP Scores across the different databases. A higher average NP Score and a distribution that closely matches that of known NPs (e.g., from COCONUT) indicate a higher fidelity to natural product-like chemical space.

Structural Novelty Assessment:

- Perform a pairwise structural similarity analysis (e.g., using Tanimoto coefficient based on molecular fingerprints) between the AI-generated library and the known NP database.

- The proportion of generated compounds that fall below a set similarity threshold to any known NP can be reported as a metric of novelty [11].

The workflow below visualizes the cheminformatics pipeline for benchmarking database content.

Cheminformatics Benchmarking Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key software, databases, and tools that are essential for modern computational natural products research, as featured in the cited experimental protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Products Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SciFinder [10] | Commercial Database | Provides authoritative, curated data on substances, reactions, and patents for dereplication and literature review. |

| COCONUT [11] | Open Natural Product Database | Serves as a comprehensive, open-access resource for known NPs, used for training AI models and chemical space analysis. |

| GNPS [12] | Web-Based Platform | Facilitates community-wide sharing and analysis of MS/MS data for dereplication via molecular networking. |

| RDKit [11] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Open-source software for cheminformatics tasks, including descriptor calculation, structure standardization, and fingerprint generation. |

| NP Score [11] | Computational Algorithm | Quantifies how closely a molecule's structure resembles known natural products, aiding in prioritization. |

| NPClassifier [11] | Deep Learning Tool | Classifies natural products based on their biosynthetic origin (Pathway), superclass, and class. |

| LSTM (AI Model) [11] | Deep Learning Architecture | A type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) used to generate novel, natural product-like molecular structures by learning from SMILES strings of known NPs. |

Discussion: Structural Evolution and Future Trajectories

The comparative data and experimental protocols highlight a clear structural evolution in NP databases: from curated repositories of what is known (SciFinder, COCONUT) to generative engines that explore what could be (AI-generated libraries). This marks a fundamental temporal trend from documentation to prediction. The 165-fold expansion of NP-like chemical space via a deep learning model trained on COCONUT data is a landmark demonstration of this shift [11]. This approach directly addresses the major bottlenecks in NP discovery: dereplication and resource-intensive structure elucidation, by enabling high-throughput in silico screening of vast virtual libraries before any wet-lab work begins [9] [11].

The integration of AI is now table stakes for modern platforms. SciFinder has incorporated AI-powered features like SearchSense for natural language query interpretation and retrosynthesis planning [10]. Concurrently, the broader field is seeing a rise of specialized AI models, including large language models (LLMs) fine-tuned for chemistry and life sciences, which are accelerating inverse design and property prediction [13]. The future of NP database research lies in the tight integration of these generative models with high-quality, curated experimental data, creating a synergistic loop where AI proposes novel candidates and experimental results refine the AI's predictive power. This will continue to push the boundaries of discoverable chemical space and reshape the natural products research workflow.

The field of natural products (NPs) research is undergoing a significant transformation, marked by a strategic shift from general-purpose repositories toward highly specialized databases. This evolution is driven by the need to manage the inherent complexity of natural products and to contextualize their biological activity within specific frameworks, such as traditional medical systems, unique biodiversity hotspots, or distinct taxonomic groups. The growing recognition that NPs represent more than half of all FDA-approved drugs underscores the critical importance of this systematic organization of knowledge [14]. This guide objectively compares the performance and scope of these specialized databases, framing their development within the broader thesis of structural evolution and temporal trends in NP research. The analysis reveals that this targeted approach directly confronts the challenges of data redundancy, accessibility, and the integration of traditional knowledge with modern pharmacology, ultimately accelerating targeted drug discovery and enabling the precise dereplication of known compounds.

A Systematic Comparison of Specialized Database Types

The diversification of natural product databases can be categorized into three primary themes: traditional medicine, geographic regions, and biological taxonomy. The table below provides a quantitative and functional comparison of representative databases within these categories.

Table 1: Comparison of Specialized Natural Product Databases by Theme

| Database Name | Primary Specialization | Key Features & Advantages | Reported Size (Number of Compounds) | Unique Structural Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCM Database@Taiwan [14] | Traditional Chinese Medicine | Largest TCM data source for virtual screening; downloadable 2D/3D structures. | 61,000 | Focus on relationships between herbs, ingredients, and compounds. |

| TCMID [14] [15] | Traditional Chinese Medicine | Bridges TCM and modern medicine; integrates herbal ingredients, targets, and diseases. | 25,210 compounds, 17,521 targets | Largest dataset in its field; enables herb-ingredient-target-disease network analysis. |

| CEMTDD [14] | Chinese Ethnic Minority Medicine | Integrates herbs, compounds, targets, and diseases; uses Cytoscape for network visualization. | 4,060 | Most complete database structure among comparable TCM databases at its time. |

| Nat-UV DB [16] | Geographic (Veracruz, Mexico) | Represents a coastal biodiversity hotspot; high structural diversity. | 227 | Contains 52 scaffolds not found in other NP databases; similar properties to approved drugs. |

| BIOFACQUIM [17] [16] | Geographic (Mexico) | Curated collection of NPs from Mexico. | 531 | Serves as a reference for Mexican natural product chemical space. |

| LaNAPDB [16] | Geographic (Latin America) | Aggregates natural products from multiple Latin American countries. | 13,579 | Enables regional cross-comparison of chemical diversity. |

| CNMR_Predict [18] | Taxonomic (e.g., Brassica rapa) | Creates taxon-specific databases with predicted 13C NMR data for dereplication. | Varies by taxon | Links structural data directly to taxonomic origin, streamlining identification. |

This thematic specialization directly enhances research efficacy. For traditional medicine, databases like TCMID bridge the gap between historical use and modern molecular mechanisms by establishing connections between herbal ingredients and the disease-related proteins they target [14]. Geographically focused databases like Nat-UV DB demonstrate that region-specific NPs occupy valuable and unique chemical space, with analyses showing they possess a similar size, flexibility, and polarity to approved drugs while introducing novel scaffolds [16]. Taxonomically focused resources address the critical bottleneck of dereplication—the process of identifying known compounds to avoid re-isolation. By creating specialized databases for a given species or genus, supplemented with predicted 13C NMR data, tools like CNMR_Predict drastically improve the accuracy and efficiency of compound identification from complex extracts [18].

Experimental Protocols for Database Construction and Analysis

The development and validation of specialized databases rely on rigorous, reproducible methodologies. The following workflows detail the standard protocols for constructing a geographic NP database and for conducting a temporal analysis of structural trends.

Protocol for Building a Geographic Natural Product Database

The construction of a geographically-focused database, such as Nat-UV DB, follows a meticulous process of data collection, curation, and chemoinformatic characterization [16]. The workflow for this protocol is standardized to ensure data integrity and utility.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Database Construction

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function in the Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Literature Databases (PubMed, SciFinder, etc.) | Source for identifying published compounds and their associated metadata (source organism, location). |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Data | Critical for definitive structural elucidation; used as a filter for database inclusion. |

| ChemBioDraw / MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Software for generating and curating molecular structures (e.g., SMILES strings) and standardizing formats. |

| PubChem / ChEMBL Databases | Used for cross-referencing and annotating compounds with known biological activities. |

| DataWarrior / RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkits for calculating physicochemical properties (e.g., MW, ClogP) and analyzing chemical space. |

Database Construction Workflow

Protocol for Temporal Analysis of Structural Trends

Analyzing the structural evolution of natural products over time, as performed in large-scale chemoinformatic studies, involves a systematic process of data grouping, descriptor calculation, and multi-faceted comparison [2]. The protocol is designed to uncover long-term trends in the chemical properties of NPs versus synthetic compounds (SCs).

Temporal Analysis Workflow

Key findings from such temporal analyses reveal that NPs have consistently become larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic over time, exhibiting increased structural diversity and uniqueness. In contrast, the structural evolution of synthetic compounds, while shifting, is constrained within a range governed by drug-like rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five [2].

The Structural Evolution of Natural Products and Databases

The thematic diversification of databases is a direct response to the evolving structural understanding of natural products themselves. Large-scale, time-dependent chemoinformatic analyses reveal clear trends in the chemical space of NPs, which in turn informs the design of modern databases.

Table 3: Temporal Trends in Natural Product vs. Synthetic Compound Properties

| Property Category | Key Trend in Natural Products (NPs) | Key Trend in Synthetic Compounds (SCs) | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size [2] | Consistent increase in molecular weight, volume, and heavy atom count. | Variation within a limited range, constrained by synthetic technology and drug-like rules. | NPs explore larger chemical space, necessitating databases that can handle greater complexity. |

| Ring Systems [2] | Increase in rings, ring assemblies, and non-aromatic rings; more glycosylation. | Greater prevalence of aromatic rings, especially five and six-membered; recent sharp increase in four-membered rings. | Thematic databases can focus on NPs with specific, complex ring systems valuable for drug design. |

| Structural Diversity [2] | Higher structural diversity and uniqueness; chemical space has become less concentrated. | Broader synthetic pathway diversity, but a decline in biological relevance. | Specialized databases preserve and highlight the unique, biologically relevant scaffolds of NPs. |

These evolutionary trends highlight the critical role of specialized databases. As NPs continue to be discovered with increasing structural complexity, broadly-scoped databases risk becoming "flat" and difficult to mine for specific insights. The fragmentation into thematic, geographic, and taxonomic categories creates a more navigable and semantically rich data ecosystem. This allows researchers to ask more targeted questions, such as "What are the characteristic NPs from Brazilian plants?" or "Which TCM herbs contain compounds predicted to modulate GPCRs?", a family of proteins targeted by approximately one-third of all marketed drugs [19]. This structured, specialized approach is essential for unlocking the full potential of natural products in modern drug discovery.

The systematic documentation of natural products (NPs) represents a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and chemical biology. The compilation of over 400,000 non-redundant chemical structures in open collections marks a significant milestone in the field, enabling unprecedented analysis of nature's structural diversity and its temporal evolution. This vast repository of chemically characterized compounds provides researchers with essential resources for understanding the structural principles that govern biological activity in small molecules derived from nature. The availability of these large-scale, curated datasets has transformed natural product research from a discipline focused on individual compound discovery to one capable of data-driven exploration of chemical space and its relationship to biological function [11] [20].

Understanding the growth patterns and structural trends within these natural product collections offers valuable insights for drug development professionals seeking to leverage nature's innovations. As these databases continue to expand, they capture the historical progression of natural product discovery while simultaneously revealing how technological advances in isolation, purification, and structure elucidation have shaped our understanding of nature's chemical inventory. This quantitative assessment of natural product compilation provides both a retrospective analysis of past discoveries and a foundation for predicting future directions in the field [2].

Quantitative Landscape of Major Natural Product Databases

Database Scale and Composition

The landscape of natural product databases has expanded dramatically in recent years, with several major initiatives compiling comprehensive collections of characterized structures. The most significant development has been the creation of the COCONUT (Collection of Open Natural Products) database, which represents the largest open-access resource with 406,919 documented and unique natural products as of its most recent compilation [11]. This massive collection has been assembled from diverse sources including terrestrial plants, marine organisms, and microorganisms, representing the cumulative output of natural product research spanning several decades.

Other notable databases have contributed to this ecosystem, though often with more specialized foci. The African Natural Products Database (ANPDB) and Latin American Natural Product Database (LANaPD) have systematically cataloged compounds from their respective geographical regions, addressing previous biases in natural product representation [21]. Similarly, the Traditional Chinese Medicine Compound Database (TCMCD) has documented the chemical constituents of medically important plants used in traditional healing practices [2]. While these specialized collections vary in size, their integration into the broader natural product informatics infrastructure has been essential for capturing the full spectrum of chemical diversity found in nature.

Table 1: Major Natural Product Databases and Their Key Characteristics

| Database Name | Number of Compounds | Scope | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| COCONUT | 406,919 | Comprehensive global collection | Open |

| African Natural Products Database (ANPDB) | Not specified | African terrestrial and marine sources | Not specified |

| Latin American Natural Product Database (LANaPD) | Not specified | Latin American biodiversity | Not specified |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine Compound Database (TCMCD) | Not specified | Traditional Chinese medicinal plants | Not specified |

Temporal Expansion Patterns

The growth of natural product collections follows a distinctive temporal pattern that reflects both technological innovation and changing research priorities. Analysis of the Dictionary of Natural Products reveals that approximately 1.1 million natural products have been characterized when considering both characterized and partially characterized compounds, though the 406,919 fully characterized structures in COCONUT represent the highest-confidence subset suitable for detailed cheminformatic analysis [2]. This expansion has not been linear; rather, specific periods of accelerated growth correspond to breakthroughs in separation technologies (such as HPLC and countercurrent chromatography) and structure elucidation methods (particularly advances in NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry) [22].

Recent analysis of temporal trends indicates that newly discovered natural products have become progressively larger and more complex over time. Molecular weight, molecular volume, and structural complexity metrics all show statistically significant increases when comparing compounds discovered in recent decades against those identified in earlier periods [2]. This trend likely reflects both the depletion of "low-hanging fruit" (simpler structures easily characterized with earlier technologies) and the increasing sophistication of analytical methods capable of resolving increasingly complex molecular architectures.

Methodological Framework for Database Compilation

Curation Workflows and Standardization Protocols

The compilation of high-quality natural product databases requires rigorous curation protocols to ensure structural accuracy and consistency across diverse sources. The COCONUT database employs a multi-stage workflow that begins with the aggregation of structural data from literature sources, patents, and existing databases, followed by a series of standardization and validation steps [11]. This process utilizes the ChEMBL chemical curation pipeline, which implements FDA/IUPAC guidelines for structure standardization and generates parent structures by removing isotopes, solvents, and salts to enable meaningful structural comparisons [11].

A critical challenge in natural product database compilation is the resolution of structural inaccuracies that have persisted in the literature. As highlighted in studies of structural revision, initial reports of natural product structures sometimes contain errors ranging from stereochemical misassignments to completely incorrect carbon skeletons [22]. Modern database curation must therefore incorporate verification mechanisms, including cross-referencing with synthetic studies and computational validation of spectroscopic data, to flag potentially problematic structures. The implementation of computer-assisted chemical structure elucidation (CASE) systems has proven particularly valuable for identifying inconsistencies between reported NMR data and proposed structures [22].

Cheminformatic Processing and Metrics

The transformation of raw structural data into a searchable, analyzable database requires the application of specialized cheminformatic tools. The RDKit toolkit serves as the workhorse for many of these operations, enabling the conversion of structural representations into canonical SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System), calculation of molecular descriptors, and generation of molecular fingerprints for similarity assessment [11]. For natural product databases specifically, the NP Score algorithm provides a quantitative measure of "natural product-likeness" by comparing atom-centered fragments and bonding patterns against known natural product structural space [11].

Additional classification is provided by the NPClassifier tool, which employs deep learning to categorize natural products according to their biosynthetic pathways based on structural features, source organism taxonomy, and reported biological activities [11]. This multi-dimensional classification system enables researchers to navigate natural product space not only by structural similarity but also by biosynthetic logic, creating bridges between chemical structures and their genetic origins. For the COCONUT database, this analysis revealed that 88% of the natural products received pathway classifications consistent with known biosynthetic categories, while the remainder may represent either novel biosynthetic classes or structures with synthetic modifications [11].

Table 2: Key Analytical Metrics for Natural Product Database Characterization

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Computational Method |

|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical Properties | Molecular weight, LogP, HBD, HBA, TPSA, rotatable bonds | RDKit |

| Structural Complexity | Number of chiral centers, fraction of sp3 carbons, molecular quadrature | RDKit-based calculations |

| Natural Product-Likeness | NP Score | Bayesian analysis of atom-centered fragments |

| Biosynthetic Classification | Pathway, superclass, class | NPClassifier deep learning model |

Structural Evolution and Temporal Trends in Natural Products

Progressive Changes in Molecular Properties

Longitudinal analysis of natural product collections reveals distinctive trends in their structural and physicochemical properties over time. A comprehensive time-dependent chemoinformatic study examining natural products discovered between early documentation and recent additions found that NPs have become larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic over successive decades [2]. Specifically, molecular weight, molecular volume, and molecular surface area all show statistically significant increases, with recently discovered natural products being substantially larger than their early counterparts [2].

This trend toward increasing molecular size is accompanied by changes in ring systems and structural frameworks. The average numbers of rings, ring assemblies, and non-aromatic rings have gradually increased in natural products over time, while the number of aromatic rings has remained relatively constant [2]. This suggests that recently discovered natural products contain more complex, fused ring systems (including bridged and spiro rings) rather than simple aromatic systems. Additionally, the glycosylation ratio (proportion of glycosylated natural products) and the mean number of sugar rings in each glycoside have both increased over time, contributing to the overall growth in molecular size and complexity [2].

Expanding Chemical Space and Structural Diversity

The chemical space covered by natural products has expanded considerably as database sizes have grown. Projection of natural product structures into physicochemical descriptor spaces reveals that newer additions occupy regions previously sparsely populated, indicating that discovery efforts are continually revealing new structural archetypes rather than simply filling in gaps between known scaffolds [11] [2]. This expansion is particularly evident in the increasing proportion of natural products that fall outside the "drug-like" chemical space defined by traditional metrics such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, suggesting that nature explores chemical possibilities beyond those typically considered in synthetic medicinal chemistry [2].

Despite this expansion, natural products maintain a distinctive structural signature that differentiates them from synthetic compounds. Comparative analysis has demonstrated that natural products contain more oxygen atoms, more chiral centers, and higher overall stereochemical complexity than synthetic compound libraries [2]. They also tend to feature more diverse ring systems with higher degrees of fusion and incorporation of medium-to-large ring sizes, reflecting the biosynthetic processes that generate them. These structural characteristics have important implications for biological activity, as they often enable natural products to interact with complex binding sites that are difficult to target with flatter, more symmetric synthetic compounds [23].

Research Applications and Experimental Methodologies

Virtual Screening and In Silico Discovery Protocols

The availability of large-scale natural product databases has enabled sophisticated virtual screening workflows that leverage these collections for drug discovery. A typical protocol begins with the preparation of the natural product library through structure standardization, tautomer enumeration, and generation of 3D conformers using tools such as RDKit or Open Babel [21] [20]. This is followed by molecular docking against protein targets of interest using platforms like AutoDock Vina or GLIDE, with results evaluated based on docking scores, interaction patterns, and consistency with known active sites [21].

Advanced virtual screening approaches incorporate pharmacophore modeling and shape-based similarity searching to identify natural products that share key functional group arrangements or molecular shapes with known active compounds without requiring precise structural similarity [21]. These methods have proven particularly valuable for natural product screening because they can identify structurally unique compounds that nevertheless share the essential features required for binding to a particular target. For example, pharmacophore-based screening identified the natural products farnesiferol B and microlobidene as activators of the G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (GPBAR1), despite their scaffolds being previously unassociated with this target [21].

Cheminformatic Analysis and Chemical Space Visualization

Systematic analysis of natural product databases employs a standardized set of computational techniques to extract meaningful patterns from structural data. The foundational methodology involves calculating molecular descriptors including molecular weight, LogP, topological polar surface area, hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, and rotatable bonds to characterize the physicochemical properties of the collection [21]. These descriptors are then visualized using techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) or t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) to project the high-dimensional chemical space into two or three dimensions for intuitive exploration [11] [21].

Scaffold analysis provides complementary information by focusing on the core structural frameworks rather than complete molecules. The Bemis-Murcko approach decomposes natural products into their ring systems and linkers, enabling quantification of scaffold diversity and identification of privileged structural motifs that recur across multiple natural products with different biological activities [2]. For natural products specifically, scaffold analysis has revealed that they contain more aliphatic rings and fewer heteroatoms (except oxygen) compared to synthetic compounds, reflecting their distinct biosynthetic origins [2].

Diagram Title: Natural Product Database Analysis Workflow

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Natural Product Database Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| COCONUT Database | Database | Comprehensive NP collection | Primary data source for analysis |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Molecular descriptor calculation, scaffold decomposition | Property profiling, structural analysis |

| ChEMBL Curation Pipeline | Standardization Protocol | Structure validation and standardization | Data preprocessing |

| NP Score | Algorithm | Quantification of natural product-likeness | Compound prioritization |

| NPClassifier | Classification Tool | Biosynthetic pathway assignment | Structural categorization |

| t-SNE | Visualization Algorithm | Dimensionality reduction for chemical space mapping | Data visualization |

| Bemis-Murcko Method | Analytical Approach | Scaffold extraction from molecular structures | Diversity analysis |

The compilation of over 400,000 non-redundant natural products in open collections represents both a remarkable achievement and a foundation for future research. These databases capture the extraordinary structural diversity evolved in nature, providing an expanding resource for drug discovery and chemical biology. The quantitative analysis of these collections reveals clear temporal trends toward larger, more complex molecular architectures while maintaining the distinctive structural features that differentiate natural products from synthetic compounds.

Looking forward, several developments promise to further expand and enhance natural product databases. The application of deep generative models has already demonstrated the potential to create virtual libraries of natural product-like structures that significantly expand beyond known compounds, with one recent effort generating 67 million natural product-like molecules - a 165-fold expansion of known natural product space [11]. As these computational approaches mature, they will likely guide targeted discovery efforts toward the most promising regions of unexplored chemical space. Additionally, continued advances in structure elucidation technologies, particularly computational prediction of NMR spectra and cryo-electron microscopy for natural product biosynthesis enzymes, will accelerate the rate of structural characterization while reducing error rates [22] [24]. Together, these developments suggest that the next decade will witness not only quantitative growth in natural product databases but also qualitative improvements in their accuracy, annotation depth, and integration with biological context.

Leveraging Database Infrastructure for Modern Drug Discovery Workflows

The identification of novel bioactive compounds is a cornerstone of drug discovery, and in this pursuit, natural products (NPs) have historically been indispensable. NPs are essential reservoirs of innovative drug discovery, with an estimated 68% of approved small-molecule drugs between 1981 and 2019 being directly or indirectly derived from them [2]. The high biological relevance of NPs is attributed to their co-evolution with proteins, resulting in structures pre-validated by nature to interact with biological macromolecules [23]. However, the exploration of NP chemical space has been transformed by digital technologies. While only approximately 400,000 NPs have been fully characterized, recent advances in deep generative modeling have enabled the creation of virtual libraries containing tens of millions of NP-like structures, representing an unprecedented expansion of accessible bioactive chemical space [11]. This evolution from physical compound collections to vast in silico databases has fundamentally enhanced their utility in virtual screening campaigns.

This guide objectively compares the performance of NP databases against other chemical libraries in virtual screening, providing researchers with a clear framework for database selection. We situate this comparison within the broader thesis of structural evolution, examining how the temporal trends in NP discovery—such as the trend towards larger, more complex structures over time—influence their current application in computational drug discovery [2].

Structural Evolution and Key Characteristics of NP Databases

Temporal Trends in NP Structural Properties

A time-dependent chemoinformatic analysis reveals that the structural characteristics of NPs have evolved significantly. Compared to synthetic compounds (SCs), NPs have become larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic over time, exhibiting increased structural diversity and uniqueness [2]. This evolution is summarized in the table below, which compares key physicochemical properties.

Table 1: Time-Dependent Comparison of Key Structural Properties between Natural Products (NPs) and Synthetic Compounds (SCs)

| Physicochemical Property | Trend in NPs Over Time | Trend in SCs Over Time | Comparative Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size (e.g., Weight, Volume) | Consistent increase | Variation within a limited, drug-like range | NPs are generally larger than SCs, a trend that has become more pronounced [2]. |

| Structural Complexity (e.g., Number of Rings) | Gradual increase | Moderate increase, with a focus on aromatic rings | NPs possess more rings but fewer ring assemblies, indicating bigger fused rings [2]. |

| Aromatic Rings | Little change over time | Clearly increasing, with constantly high six-membered rings | SCs are distinguished by a greater involvement of aromatic rings [2]. |

| Non-Aromatic Rings | Gradual increase | Little change | Most rings in NPs are non-aromatic [2]. |

| Glycosylation | Increasing ratio and sugar ring count | Not typically a major feature | Suggests recently discovered NPs are more complex [2]. |

| Hydrophobicity | Increasing over time | Governed by drug-like constraints | - |

| Overall Chemical Space | Becoming less concentrated and more diverse | Broader synthetic diversity, but declining biological relevance | The structural evolution of SCs is influenced by NPs but has not fully evolved in their direction [2]. |

Defining Modern NP and NP-Like Databases

The term "NP database" now encompasses a spectrum of resources, from collections of authentic natural products to AI-generated virtual libraries.

- Curated Databases of Known NPs: These include resources like the Dictionary of Natural Products and the COCONUT (Collection of Open Natural Products) database, which contain hundreds of thousands of characterized natural products [2] [11]. These provide the foundational data for understanding NP chemical space.

- AI-Generated NP-Like Libraries: Leveraging deep generative models trained on known NPs, these databases offer a massive expansion of NP-like chemical space. For instance, one publicly available database uses a recurrent neural network (RNN) to generate over 67 million valid, unique, natural product-like molecules, a 165-fold expansion over known NPs [11]. These molecules closely resemble the natural product-likeness score distribution of known NPs while exploring novel physiochemical and structural regions [11].

- Pseudo-Natural Product (pseudo-NP) Libraries: This design principle involves the unprecedented recombination of NP fragments to explore biological space beyond guiding NPs. The resulting pseudo-NPs are synthetically tractable compounds that inherit biological relevance while accessing unprecedented chemical space, representing a form of chemical evolution of NP structures [23].

Comparative Performance in Virtual Screening

Virtual screening (VS) performance is highly dependent on the target and the chemical library used. The following experimental data highlights how NP-derived libraries can offer distinct advantages, particularly for challenging targets.

Case Study: Targeting Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs)

Protein-protein interactions are notoriously difficult to target with small molecules due to their large, shallow interfaces. NP libraries have demonstrated exceptional performance in this area.

In a prospective virtual screening study against the SH2 domain of STAT3, a relevant PPI-type oncotarget, two distinct approaches were compared [25]:

- AI-Based uHTVS: An ultra-high-throughput virtual screen of an ultralarge synthetic library (Enamine REAL, 5.51 billion compounds) using the Deep Docking workflow.

- Knowledge-Based Approach: A "traditional" brute-force virtual screen of a natural product library containing 193,757 compounds.

Table 2: Virtual Screening Performance Against STAT3-SH2 Domain

| Screening Strategy | Library Type | Library Size | Hit Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Based uHTVS | Synthetic (Make-on-demand) | 5.51 Billion | 50.0% |

| Knowledge-Based | Natural Product Library | ~194,000 | 42.9% |

| Knowledge-Based | SH2 Domain Targeted Library | ~1,800 | Not Disclosed |

The results show that the NP library achieved a remarkably high hit rate of 42.9%, competitive with the AI-driven screen of a vastly larger synthetic library. This underscores the high "biologically relevant" quality and structural complementarity of NPs for complex targets like PPIs. The study authors noted that the increased 3D-likeness and complexity of natural products represents a powerful knowledge-based option for identifying hits against PPI targets [25].

Cheminformatic Basis for Performance

The superior performance of NP databases in certain screening contexts is rooted in their fundamental structural characteristics, which differ significantly from those of typical synthetic compounds.

- Enhanced Complexity and 3D-Shape: NPs generally have more non-aromatic rings and higher stereochemical complexity than SCs. This results in more three-dimensional, "globular" structures that are better suited to binding the complex surfaces of many therapeutic targets, especially PPIs [2] [25].

- Fragment and Substituent Differences: The molecular fragments and side chains in NPs are distinct. They contain more oxygen atoms, stereocenters, and fewer nitrogen or sulfur atoms compared to the substituents of SCs, which are rich in nitrogen, sulfur, halogens, and aromatic rings [2]. This influences drug-likeness and binding interactions.

- Coverage of Privileged Chemical Space: NPs occupy a region of chemical space that is often under-represented in synthetic libraries. Cheminformatic analyses confirm that NPs and pseudo-NPs exhibit high NP-likeness scores and cover a diverse and unique chemical space that overlaps with biologically relevant regions [11] [23].

Essential Protocols for Virtual Screening with NP Databases

Standard Workflow for NP Database Screening

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for conducting a virtual screen using an NP database, integrating steps from cited experimental protocols.

Virtual Screening Workflow with NP Databases

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

A. Library Curation and Preparation (Based on [25] [11])

- Data Retrieval: Obtain SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) or structure data files from public NP databases (e.g., COCONUT) or commercial suppliers.

- Chemical Standardization: Process structures using a standardized pipeline, such as the ChEMBL chemical curation pipeline, to check for validity, remove duplicates, de-salt, and generate canonical representations [11].

- Filtering: Apply filters to remove compounds with undesirable properties. A critical step is the removal of Pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) to minimize false positives [25].

- Descriptor Calculation: Use toolkits like RDKit to calculate key physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, rotatable bonds) for library characterization [11].

B. Molecular Docking and Hit Identification (Based on [25])

- Target Preparation: Select a high-quality X-ray crystal structure of the protein target. Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and defining the binding site.

- Retrospective Validation (Optional but Recommended): Perform a control docking with a small set of known actives and decoy molecules to calculate performance metrics like the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) and Enrichment Factor (EF). This validates the docking protocol for your specific target [25].

- High-Throughput Docking: Execute the docking run against the prepared and filtered NP library. For ultra-large libraries, consider AI-accelerated workflows like Deep Docking to reduce computational cost [25].

- Hit Selection: Rank compounds based on docking scores and inspect the top-ranking compounds visually to assess the quality of binding poses and protein-ligand interactions before selecting a final shortlist for experimental testing.

Table 3: Essential Resources for NP-Based Virtual Screening

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in VS | Example Sources / Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curated NP Databases | Data Repository | Provides authentic, characterized natural product structures for screening. | COCONUT, Dictionary of Natural Products [2] [11] |

| Generative AI Models | Software/Algorithm | Expands NP chemical space by generating novel, NP-like virtual compounds. | SMILES-based RNN/LSTM [11] |

| Cheminformatics Toolkits | Software Library | Handles chemical data standardization, descriptor calculation, and analysis. | RDKit [11] |

| Docking Software | Software Suite | Predicts binding poses and affinity of database compounds against a protein target. | AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD [25] |

| PAINS Filter | Computational Filter | Identifies and removes compounds with known promiscuous, assay-interfering motifs. | Various implementations in RDKit/KNIME [25] |

| Pseudo-NP Design Principle | Conceptual Framework | Guides synthesis of novel, biologically relevant compounds by recombining NP fragments. | - [23] |

The integration of natural product databases into virtual screening workflows provides a powerful and complementary strategy to synthetic library screening. The unique structural evolution of NPs—toward greater complexity and three-dimensionality—makes their chemical space particularly valuable for targeting challenging mechanisms like protein-protein interactions, as evidenced by high virtual screening hit rates [2] [25].

The future of NP-powered virtual screening lies in the continued expansion and intelligent exploitation of NP-like chemical space. Trends point towards the increased use of deep generative models to create vast virtual libraries that retain the biological relevance of NPs while exploring unprecedented structural regions [11]. Furthermore, the pseudo-NP concept, which involves the synthetic recombination of NP fragments, represents a powerful form of "chemical evolution" for creating high-quality screening libraries that bridge the gap between natural inspiration and synthetic feasibility [23]. As these computational and synthetic strategies mature, they will further solidify the role of natural product-informed databases as indispensable tools for in silico lead identification.