Terrestrial vs. Marine Natural Products: A Comparative Analysis of Chemical Diversity and Therapeutic Potential in Drug Discovery

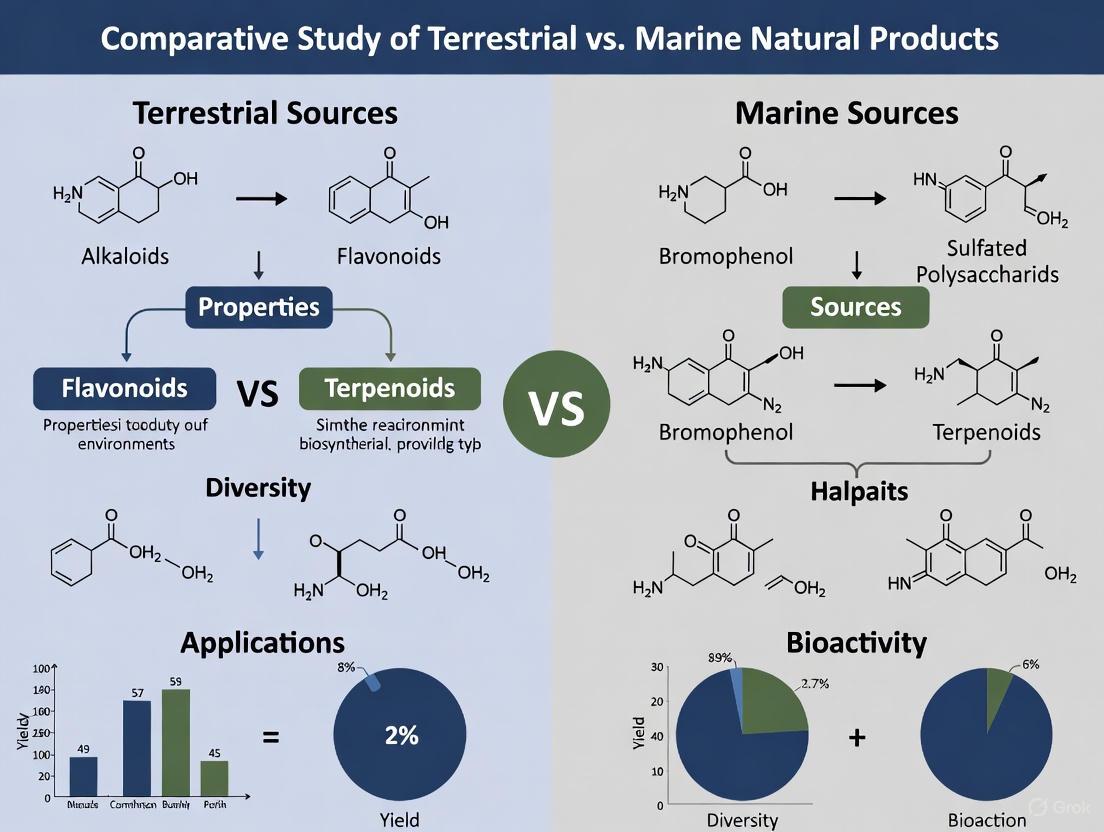

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of natural products derived from terrestrial and marine environments, focusing on their distinct chemical properties, biological activities, and applications in modern drug discovery.

Terrestrial vs. Marine Natural Products: A Comparative Analysis of Chemical Diversity and Therapeutic Potential in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of natural products derived from terrestrial and marine environments, focusing on their distinct chemical properties, biological activities, and applications in modern drug discovery. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, the article explores the foundational history and sources of these compounds, compares innovative extraction and screening methodologies, and addresses key challenges in optimization and scalability. It further presents a rigorous comparative analysis of their clinical success and validation, synthesizing cheminformatic data and case studies of FDA-approved drugs. The article concludes by evaluating future directions, including the role of AI and sustainable practices, offering a strategic overview for guiding future bioprospecting and pharmaceutical development.

Origins and Ecosystems: Exploring the Fundamental Landscapes of Terrestrial and Marine Natural Products

The discovery of morphine from the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) in the early 19th century by Friedrich Wilhelm Adam Sertürner marked the dawn of alkaloid chemistry and provided medicine with one of its most potent analgesics [1]. This seminal event established terrestrial plants as a cornerstone of pharmacognosy. For over a century, terrestrial ecosystems remained the primary source of biologically active natural products. However, the global shift towards natural therapeutic agents, driven by their often lower toxicity compared to synthetic compounds, has intensified the search for novel chemical scaffolds from underexplored sources [2]. The ocean, hosting the largest concentration of species on the planet, has emerged as a formidable frontier in natural product discovery. This guide provides a comparative analysis of terrestrial and marine-originated alkaloids, focusing on their historical context, physicochemical properties, biological activities, and the experimental frameworks used in their investigation.

Historical Milestones and Key Alkaloid Transitions

Table 1: Historical Milestones in Alkaloid Discovery from Terrestrial and Marine Sources

| Era | Terrestrial Milestones | Marine Milestones |

|---|---|---|

| 19th Century | Isolation of morphine from opium poppy (c. 1804) [1]. | — |

| Early-Mid 20th Century | János Kabay's industrial method for morphine extraction from poppy straw (1925-1931) [1]. | — |

| Mid-Late 20th Century | Total synthesis of morphine achieved (1952) and refined [3] [4]. | First approved marine-derived drug, Ara-C (Cytarabine) from sponge (1969) [5]. |

| 21st Century | Ongoing synthetic and pharmacological refinement of morphinans [1]. | Approval of marine-derived drugs like Eribulin (Halichondrin B analog) for breast cancer (2010); isolation of 186+ new marine indole alkaloids (2016-2021) [6] [5]. |

The transition from terrestrial to marine exploration has significantly diversified the alkaloid chemical space. While terrestrial alkaloids like morphine are often characterized by their complex polycyclic structures and historical significance in medicine and synthetic chemistry [3] [4], marine alkaloids introduce a wealth of novel scaffolds. The period from 2016 to 2021 alone saw the discovery of 186 previously undescribed marine indole alkaloids from sources including fungi, bacteria, sponges, and bryozoans [6]. These compounds are not merely structural curiosities; they are a source of diverse biological activities with clinical potential, as demonstrated by trabectedin (from a tunicate) and eribulin (a synthetic analog of sponge-derived halichondrin B), which are approved for cancer treatment [5].

Comparative Analysis: Terrestrial vs. Marine Alkaloids

Structural and Physicochemical Properties

Cheminformatic analyses reveal distinct structural trends between terrestrial natural products (TNPs) and marine natural products (MNPs), which are reflected in their respective alkaloid families.

Table 2: Comparative Physicochemical and Structural Profile [7]

| Parameter | Terrestrial Natural Products (TNPs) | Marine Natural Products (MNPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Average Molecular Size | Generally smaller | Larger, more complex on average |

| Solubility | Higher | Lower |

| Nitrogen Atoms | Fewer | More common |

| Oxygen Atoms | More common | Fewer |

| Halogen Atoms | Rare | Common, particularly Bromine |

| Frequent Ring Systems | Stable, shorter ring systems | More long chains and large rings (e.g., 8-10 membered) |

| Unique Scaffolds | — | Ester bonds connected to 10-membered rings |

| Drug-Likeness | Mostly drug-like | Slightly more drug-like |

These differences stem from divergent evolutionary pressures and biosynthetic pathways. Marine organisms frequently employ unique biosynthetic logic, leading to alkaloids with more long chains, large rings (especially 8- to 10-membered), and halogen atoms (notably bromine) [7]. The presence of nitrogen and halogen atoms enhances the ability of marine alkaloids to interact with biological targets through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions [5].

Biological Activity and Therapeutic Potential

Table 3: Comparative Biological Activities of Terrestrial and Marine Alkaloids

| Alkaloid Class/Source | Example Compounds | Reported Biological Activities | Key Molecular Targets/Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial Morphinans | Morphine, Codeine, Oxycodone [1] | Potent analgesic, severe side effects (respiratory depression, addiction) [8] | μ-opioid receptor (μOR) agonist [8] |

| Marine Indole Alkaloids | Fusariumindole C, Pseudellone D [6] | Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, cytotoxic [6] | Diverse; often unexplored |

| Marine Anti-inflammatory Alkaloids | Neoechinulin A, Chaetoglobosin Fex [9] | Anti-inflammatory | Inhibition of NF-κB pathway, MAPK signaling; reduction of iNOS, COX-2, pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) [9] |

| Marine Sponge Guanidine Alkaloids | Crambescidin 800 [5] | Cytotoxic (against triple-negative breast cancer) | Not fully elucidated; induces cell death |

| Marine Bacterial Peptides | A58365A (from Streptomyces) [8] | Potential analgesic | μ-opioid receptor agonist (in silico prediction) [8] |

The therapeutic profiles highlight a key distinction: while classic terrestrial alkaloids like morphine are highly specific and potent but burdened with severe side effects, marine alkaloids often exhibit broader, multi-target mechanisms that can be advantageous for complex diseases like cancer. For instance, marine alkaloids can induce cancer cell apoptosis, block the cell cycle, inhibit angiogenesis, and target oncogenic pathways simultaneously [5]. This multi-faceted activity is a hallmark of many marine-derived compounds.

Experimental Protocols for Alkaloid Research

Isolation and Identification from Marine Sediment Bacteria

This protocol, adapted from studies searching for novel bioactive compounds, outlines the process from sample collection to compound identification [8].

- Sample Collection: Marine sediment samples are collected from coastal areas (e.g., at depths of 2-3 m), stored in sterile bags, and kept at 4°C.

- Strain Isolation and Cultivation:

- Samples are air-dried to reduce fast-growing bacteria.

- Dilution is performed in sterile seawater, followed by moderate heat treatment (55°C for 6 min) to enrich for heat-resistant actinobacteria.

- Aliquots are spread on various culture media (e.g., Casein Starch Agar, Marine Agar) to promote the growth of diverse bacterial taxa.

- Bioactivity Screening:

- Isolated bacterial strains are cultured on production media for ~14 days.

- Bioactivity is assessed using the agar cylinder method against pathogenic bacteria (e.g., S. aureus, E. coli) and fungi.

- Cylinders of bacterial culture are placed on agar seeded with test microorganisms. After diffusion at 4°C, plates are incubated and inhibition zones are measured.

- Molecular Identification:

- Genomic DNA is extracted from active strains.

- The 16S rRNA gene is amplified via PCR with universal primers (27F and 1525R) and sequenced for taxonomic classification.

- Metabolite Profiling & Identification:

- Secondary metabolites are analyzed by Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRESIMS).

- This technique identifies known compounds and flags potentially novel metabolites based on their mass spectra.

Protocol for Assessing Anti-inflammatory Activity

This standard cell-based protocol is used to evaluate the anti-inflammatory potential of isolated alkaloids [9].

- Cell Culture: Murine macrophage cell lines (e.g., RAW 264.7 or BV2) are cultured in appropriate media.

- Treatment and Stimulation:

- Cells are pre-treated with various concentrations of the test alkaloid.

- Inflammation is induced by stimulating the cells with bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

- Measurement of Inflammatory Markers:

- Nitric Oxide (NO): The accumulation of nitrite, a stable oxidative product of NO, in the culture supernatant is measured using the Griess reaction.

- Pro-inflammatory Cytokines: The production of cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 is quantified using Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA).

- Protein Expression: The expression levels of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) are analyzed via western blotting.

- Mechanistic Studies:

- To elucidate the mechanism, the effect of the alkaloid on key signaling pathways (NF-κB and MAPK) is investigated.

- This involves western blotting to assess the inhibition of IκB-α degradation, translocation of the NF-κB p65 subunit to the nucleus, and phosphorylation of p38, ERK, and JNK MAPKs.

In Silico Analysis of Opioid Receptor Agonists

This computational approach helps identify and prioritize potential analgesic compounds from marine sources [8].

- Ligand and Target Preparation:

- 3D structures of identified marine bacterial compounds are generated.

- The crystal structure of the μ-opioid receptor (e.g., PDB ID: 5C1M) is prepared for docking by removing water molecules and adding hydrogen atoms.

- Molecular Docking:

- Compounds are docked into the active site of the receptor using docking software.

- The binding pose and affinity (docking score) of each compound are predicted and compared to a reference ligand like morphine.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations:

- The stability of the top-ranking ligand-receptor complex is assessed through MD simulations (e.g., 100 ns) in a solvated lipid bilayer environment.

- Parameters like root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) are analyzed to evaluate complex stability.

- Binding Free Energy Calculations:

- The MM/GBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area) method is used to calculate the binding free energy of the ligand-receptor complex, providing a more reliable estimate of binding affinity.

Visualization of Key Pathways and Workflows

Anti-inflammatory Mechanism of Marine Alkaloids

Many marine alkaloids, such as Neoechinulin A and Chaetoglobosin Fex, exert their effects by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway, a central regulator of inflammation [9].

Workflow for Marine Alkaloid Discovery and Evaluation

This diagram outlines the comprehensive journey of a marine alkaloid from initial discovery to mechanistic evaluation, integrating both experimental and computational approaches [6] [8] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Alkaloid Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Various Culture Media (e.g., Casein Starch Agar, Marine Agar) [8] | Selective isolation and cultivation of diverse marine bacteria. |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [9] | Standard reagent to induce inflammation in cell-based assays (e.g., RAW 264.7 macrophages). |

| Griess Reagent [9] | Quantifies nitric oxide (NO) production in anti-inflammatory screens. |

| ELISA Kits (for TNF-α, IL-6, etc.) [9] | Measure cytokine levels in cell culture supernatants with high sensitivity. |

| Antibodies for Western Blotting (iNOS, COX-2, IκB-α, phospho-proteins) [9] | Analyze protein expression and signaling pathway modulation. |

| LC-HRESIMS System [8] | High-resolution metabolite profiling and identification of novel alkaloids. |

| Crystallographic μ-Opioid Receptor (e.g., 5C1M) [8] | Target structure for in silico docking studies of potential analgesics. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) [8] | Simulate ligand-receptor interactions and calculate binding free energies. |

The journey from morphine to marine alkaloids represents a paradigm shift in natural product discovery. While terrestrial alkaloids provided foundational scaffolds and drugs, marine alkaloids offer a vast reservoir of chemically distinct compounds with unique mechanisms of action. The comparative analysis reveals that marine alkaloids frequently possess more complex structures, including halogens and large rings, and exhibit broader, multi-target therapeutic potential, particularly in oncology and inflammation. The future of this field relies on continued exploration of underexplored marine niches, the application of advanced cheminformatic tools for comparison [7] [10], and the use of integrated experimental and computational protocols to efficiently translate these marine treasures into novel therapeutic agents.

The relentless evolutionary competition in terrestrial and marine ecosystems has fueled an unparalleled chemical arms race, driving organisms to produce a vast arsenal of bioactive secondary metabolites. For drug discovery professionals, these natural products represent evolution-optimized scaffolds with pre-validated biological activity, offering distinct advantages over purely synthetic libraries [11]. While terrestrial plants and microorganisms have traditionally served as the cornerstone of pharmacognosy, covering approximately 70% of documented natural products, the ecological and chemical uniqueness of marine environments has positioned them as a formidable frontier for discovering novel bioactive compounds [12] [13].

The fundamental distinction between these two worlds lies in their evolutionary pressures. Terrestrial organisms typically compete in stable, resource-limited environments, favoring metabolites for competitive growth and herbivore defense. In contrast, marine organisms, particularly sessile invertebrates like sponges and corals in densely populated benthic zones, have developed potent chemical defenses against predation, fouling, and infection in the absence of physical protection [13]. This divergence has produced systematic variations in molecular properties, biological targets, and drug discovery workflows that researchers must navigate effectively.

Comparative Analysis: Structural and Physicochemical Properties

Direct chemoinformatic comparisons reveal how evolutionary pressures have shaped distinct structural landscapes in terrestrial versus marine natural products. A time-dependent analysis of over 186,000 compounds from each domain demonstrates significant and diverging evolutionary trajectories in molecular size, complexity, and hydrophobicity [14].

Table 1: Comparative Physicochemical Properties of Terrestrial and Marine Natural Products

| Property | Terrestrial Natural Products | Marine Natural Products | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Generally smaller; constrained growth over time [14] | Larger and increasing; MW consistently higher [14] | Marine compounds access more complex binding interfaces |

| Ring Systems | Higher proportion of aromatic rings [14] | More non-aromatic, larger fused rings (e.g., bridged, spiral) [14] | Greater structural rigidity and 3D complexity in marine compounds |

| Heteroatom Composition | More nitrogen atoms [14] | More oxygen and halogen atoms [14] [12] | Distinct electronic properties and hydrogen bonding capacity |

| Hydrophobicity | Moderate, within drug-like range [14] | Higher, more hydrophobic character [14] | Differential membrane permeability and distribution profiles |

| Structural Diversity | High in specific classes (e.g., terpenoids, flavonoids) [12] | Exceptional scaffold diversity and uniqueness [14] [13] | Marine library covers more unique chemical space for screening |

Marine natural products exhibit expanding structural complexity over time, with increasing numbers of rings, ring assemblies, and glycosylation patterns. Notably, the glycosylation ratios and mean number of sugar rings in glycosides have shown gradual increases in newer marine compounds, enhancing their target recognition capabilities [14]. Terrestrial compounds, while diverse, evolve within more constrained physicochemical boundaries, influenced by their specific ecological roles in plant-herbivore interactions [11].

Biodiversity and Source Organisms: A Taxonomic Perspective

The phylogenetic breadth of source organisms differs dramatically between terrestrial and marine environments, directly influencing the structural diversity of their metabolic outputs.

Table 2: Biodiversity and Source Organisms of Bioactive Natural Products

| Category | Terrestrial Sources | Marine Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant Producers | Dicotyledons (83.7%), Monocotyledons (8.1%), Gymnosperms (3%) [12] | Sponges, Ascidians, Bryozoans, Mollusks, Cnidarians [15] [13] |

| Key Taxa | Compositae, Leguminosae, Labiatae families [12] | Phyla with no terrestrial representatives (sponges, echinoderms) [13] |

| Microbial Sources | Soil-derived actinomycetes, fungi [15] | Sponge-associated bacteria, marine sediments, cyanobacteria [15] [16] |

| Chemical Hotspots | Specific plant families with specialized metabolism [12] | Coral reefs, deep-sea vents, biodiversity hotspots [16] [13] |

| Representative Compounds | Morphine (alkaloid), Taxol (diterpenoid), Quercetin (flavonoid) [12] | Ecteinascidin-743 (alkaloid), Bryostatin (polyketide), Spongothymidine (nucleoside) [13] |

Marine environments host 34-35 known animal phyla, with approximately 20 having no terrestrial representatives, creating a vast reservoir of unique biochemistry [13]. Marine invertebrates such as sponges, tunicates, and bryozoans—particularly those lacking physical defenses—have evolved sophisticated chemical defense systems, producing potent secondary metabolites that often show exceptional bioactivity against human disease targets [16] [13]. Interestingly, many compounds initially isolated from marine invertebrates are now suspected to be produced by their associated microbial symbionts, adding another layer of complexity to marine biodiscovery [12] [13].

Experimental Workflows in Natural Product Drug Discovery

While the fundamental approaches to terrestrial and marine natural product discovery share similarities, key distinctions exist in collection, processing, and dereplication strategies due to differences in source material complexity and compound abundance.

For marine natural products, the workflow begins with specialized collection methods often requiring scuba or deep-sea sampling equipment [13]. The extreme rarity of many marine compounds presents significant challenges, with some potent metabolites available only in trace quantities (e.g., 1-5 kg of halichondrin requires 3,000-16,000 metric tons of sponge biomass) [11]. This scarcity has driven innovations in sustainable sourcing, including aquaculture, cell culture, and molecular biology approaches to express biosynthetic gene clusters in heterologous microbial hosts [13].

Terrestrial natural product discovery benefits from established cultivation and harvesting practices, though sustainable sourcing remains a consideration [11]. Dereplication strategies for terrestrial compounds can leverage extensive existing databases of plant metabolites, while marine dereplication must account for the higher incidence of truly novel scaffolds [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for Natural Product Research

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Terrestrial Applications | Marine Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Metabolite profiling & dereplication | Chemical fingerprinting of plant extracts [16] | Identifying novel marine scaffolds; GNPS molecular networking [11] |

| Advanced NMR (1D/2D) | Structural elucidation | Determining stereochemistry of complex alkaloids [15] | Characterizing unprecedented marine skeletons [17] [13] |

| HREIMS/FTIR | Molecular formula determination | Functional group identification in plant compounds [15] | Structural analysis of marine steroids & polyketides [17] |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction | Green extraction technology | Extraction of plant essential oils [18] | Isolation of thermolabile marine metabolites [18] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Virtual screening & target prediction | Predicting plant compound-protein interactions [17] | Validating marine ligand binding to viral targets [17] |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Predictive bioactivity modeling | QSAR modeling of terrestrial compounds [17] | IC₅₀ prediction for marine antivirals [17] |

Modern technological advances have revolutionized both fields. LC-MS/MS systems coupled with the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform enable rapid dereplication of known compounds, directing research toward novel chemotypes [11]. For marine researchers, advanced NMR techniques are particularly crucial for characterizing unprecedented carbon skeletons with novel ring systems [17]. Emerging technologies like machine learning-based predictive models now offer researchers the ability to forecast bioactivity (e.g., IC₅₀ values) from structural descriptors, potentially accelerating the early discovery phase for both terrestrial and marine compounds [17].

The complementary nature of terrestrial and marine natural products provides drug discovery researchers with a rich chemical landscape to address evolving therapeutic challenges. Terrestrial sources offer well-characterized scaffolds with established structure-activity relationships, while marine sources deliver unprecedented chemotypes with novel mechanisms of action, particularly valuable for targeting resistant diseases [15] [13].

Future progress will depend on integrated approaches that leverage technological advancements across both domains. Sustainable sourcing through cultivation, synthesis, and heterologous expression will address supply chain challenges [13]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning will accelerate discovery by predicting bioactivity and optimizing lead compounds [12] [17]. Most importantly, recognizing the ecological context of natural products—understanding that these compounds evolved for specific biological roles in their native environments—provides a more rational foundation for bioprospecting efforts that aligns with conservation and sustainable use of global biodiversity [11].

Natural products remain a cornerstone of drug discovery, with approximately 50% of all clinically approved drugs originating from natural sources or their derivatives [16]. The comparative analysis of terrestrial and marine ecosystems reveals a fundamental divergence in their chemical and biological properties. Terrestrial plants, the historical foundation of pharmacopeia, provide well-characterized classes such as terpenoids and flavonoids. In contrast, the marine environment, representing 80% of the planet's biodiversity with 34-35 known animal phyla, produces structurally unique metabolites with novel mechanisms of action and higher incidence of significant bioactivity [12] [13]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these domains, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols to inform research and development strategies.

Comparative Analysis of Key Bioactive Compound Classes

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Major Bioactive Compound Classes

| Feature | Terrestrial Terpenoids | Marine Terpenoids | Terrestrial Flavonoids | Unique Marine Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Diversity | High structural variety; predominantly from dicotyledons (83.7%) [12] | Unprecedented skeletons (e.g., 3,4-secomeroterpenoid); extensive halogenation [19] | Extensive; ~50% of Leguminosae compounds are flavonoids [12] | Novel scaffolds (pyrroloiminoquinones, polyketides) [20] [19] |

| Source Organisms | Plants (Compositae, Leguminosae, Labiatae) [12] | Sponges, soft corals, marine microorganisms [12] [19] | Plants, fruits, vegetables [12] | Sponges, tunicates, cyanobacteria, mollusks [12] [16] |

| Prominent Bioactivities | Antineoplastic (Limonene, Celastrol) [12] | Cytotoxicity, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial [19] [21] | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory [12] | Potent cytotoxicity, novel antimicrobial mechanisms [20] [16] |

| Drug Development Success | Multiple approved drugs; 44 products from Leguminosae alone [12] | Several in clinical trials; inspired synthetic derivatives (Ara-C) [12] [13] | Numerous nutraceuticals; some pharmaceutical applications [12] | 15-20 approved drugs (e.g., Ziconotide, Trabectedin) [12] [16] [13] |

Table 2: Experimental Bioactivity Data for Selected Marine Natural Products (2020-2025)

| Compound Name | Source Organism | Class | Bioassay | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudoceranoid D | Sponge Pseudoceratina purpurea | Sesquiterpene | Cytotoxicity (H69AR, K562, MDA-MB-231 cells) | IC₅₀: 7.74, 3.01, 9.82 μM | [19] |

| 19-methoxy-dictyoceratin-A | Sponge Dactylospongia elegans | Sesquiterpene quinone | Cytotoxicity (DU145, SW1990, Huh7, PANC-1 cells) | IC₅₀: 17.4-37.8 μM | [19] |

| Arenarialins A, B, D | Sponge Dysidea arenaria | Sesquiterpene quinone meroterpenoid | TNF-α inhibition in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages | Significant inhibition | [19] |

| Discorhabdin Analogs | Sponge Latrunculia sp. | Pyrroloiminoquinone alkaloids | Cytotoxicity (A549 cells) | IC₅₀: 4.3-23.9 μM | [20] |

| Penitalarin D | Marine fungus Talaromyces sp. | Trinor-sesterterpenoid | Hepatoprotection in OGD/R model | Reduced hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury | [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Bioactive Compound Research

Standard Workflow for Marine Natural Product Discovery

The systematic approach to marine natural product discovery involves multiple validated stages:

Sample Collection and Authentication: Marine organisms are collected with precise geographical documentation [23]. For sponges, taxonomic identification is confirmed, and voucher specimens are deposited. Sustainable collection practices are mandatory, with researchers advised to "collect only what you need" to preserve biodiversity [23].

Biomass Extraction: Fresh or frozen biomass is typically extracted using organic solvents. Common protocols use methanol, dichloromethane, or ethyl acetate in sequential extraction [19] [21]. Techniques may include sonication or homogenization to improve extraction efficiency [21].

Bioassay-Guided Fractionation: Crude extracts are subjected to initial biological screening. Active extracts are fractionated using vacuum liquid chromatography or solid-phase extraction. Common elution systems include stepwise gradients of n-hexane/EtOAC, chloroform/methanol, or methanol/water [19] [21].

Compound Isolation: Active fractions undergo repeated chromatographic separation using techniques including:

- Normal and reverse-phase HPLC

- Size-exclusion chromatography (Sephadex LH-20)

- Counter-current chromatography [16]

Structure Elucidation: Pure compounds are characterized through:

Bioactivity Assessment: Isolated compounds are evaluated in disease-relevant assays:

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Marine Natural Product Discovery

Specific Bioassay Methodologies

Cytotoxicity Assessment: The SRB (sulforhodamine B) or MTT assays are performed according to established protocols [19]. Cells are seeded in 96-well plates and incubated with test compounds for 48-72 hours. IC₅₀ values are calculated using non-linear regression analysis of dose-response curves.

Anti-inflammatory Screening: RAW264.7 macrophages are stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) in the presence of test compounds [19]. TNF-α and IL-6 production is quantified using ELISA after 18-24 hours. Cell viability is assessed concurrently to exclude cytotoxic effects.

Antioxidant Evaluation: DPPH radical scavenging: Compounds are mixed with 0.1 mM DPPH in methanol [21]. Absorbance is measured at 517nm after 30 minutes. Intracellular ROS measurement: Cells are loaded with DCFH-DA dye, stimulated with tert-butyl hydroperoxide, and fluorescence is quantified [21].

Antimicrobial Profiling: Against ESKAPE pathogens using broth microdilution according to CLSI guidelines [22] [24]. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) are determined after 18-24 hours incubation.

Pathway Analysis and Molecular Mechanisms

Figure 2: Molecular Mechanisms of Marine Natural Products

Marine-derived compounds exhibit distinct mechanisms of action compared to terrestrial counterparts. For example, trabectedin from the sea squirt Ecteinascidia turbinata binds to the DNA minor groove, bending the helix to trigger a cascade affecting transcription factors, DNA repair pathways, and cell cycle progression [13]. Marine terpenoids like pseudoceranoids from sponges demonstrate multi-target effects, including pro-apoptotic signaling through mitochondrial pathways and inhibition of key inflammatory mediators like TNF-α and IL-6 [19]. The unique structural features of marine metabolites, particularly halogenation and complex ring systems, enable interactions with biological targets that are less common with terrestrial compounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Natural Product Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Media | Compound separation | Fractionation and purification | Sephadex LH-20, C18 reverse-phase silica [19] [21] |

| Bioassay Kits | Biological activity screening | Target-specific activity assessment | ELISA kits (TNF-α, IL-6), cell viability assays (MTT, SRB) [19] [22] |

| Cell Lines | In vitro efficacy testing | Disease models for compound screening | RAW264.7 (inflammation), A549 (lung cancer), HepG2 (liver cancer) [19] [22] |

| Culture Media | Microorganism cultivation | Biomass generation for compound production | Marine broth, ISP2 medium for actinomycetes [20] [24] |

| Analytical Standards | Compound identification | NMR and MS reference materials | Commercial terpenoid standards, deuterated solvents [19] [21] |

| ESKAPE Pathogen Panels | Antimicrobial testing | Resistance profiling | Clinical isolates of MRSA, VRE, CRAB [22] [24] |

The comparative analysis demonstrates that marine natural products offer greater structural novelty and a higher incidence of significant bioactivity compared to terrestrial sources, though terrestrial products provide greater historical success and established research protocols [12] [13]. Current trends indicate accelerated discovery from marine sources, with hundreds of novel metabolites being reported annually from sponges alone [19]. Future research will be shaped by sustainable sourcing practices, including microbial cultivation and partial synthesis to preserve biodiversity [23], and enhanced by technological advances in genomics, metabolomics, and artificial intelligence for targeted discovery [12]. The complementary strengths of both terrestrial and marine sources will continue to drive innovation in natural product-based drug development, particularly against challenging targets like multi-drug resistant pathogens and complex chronic diseases.

In the natural world, chemical diversity represents one of evolution's most sophisticated strategies for survival. Organisms across terrestrial and marine ecosystems produce a vast arsenal of specialized metabolites that serve as their primary language of ecological interaction—defending against predators, competing for resources, attracting symbionts, and adapting to environmental challenges. This comparative guide examines how these distinct ecological pressures have driven the evolution of dramatically different chemical defense and adaptation strategies in terrestrial versus marine environments, with profound implications for drug discovery and pharmaceutical development.

The fundamental dichotomy begins with the contrasting evolutionary pressures of these environments. Marine organisms, including sponges, tunicates, and corals, often lack physical defenses and rely heavily on chemical warfare for survival [12]. These sessile or slow-moving marine invertebrates dominate the discovery of marine natural products, accounting for approximately 75% of bioactive marine compounds identified between 1985 and 2012 [12]. In contrast, terrestrial plants face different selective pressures—herbivory, pathogen attack, and environmental stressors—leading to the production of complex mixtures of metabolites where synergistic effects collectively contribute to their pharmacological properties [12].

For drug discovery professionals, understanding these ecological drivers provides valuable insights for bioprospecting strategies. The structural novelty emerging from marine chemical ecology is demonstrated by the higher incidence of significant bioactivity and structural novelty in marine-derived natural products compared to terrestrial sources [12]. This review provides a systematic comparison of these ecological drivers, their resulting chemical strategies, and the experimental approaches essential for harnessing nature's chemical ingenuity for human therapeutics.

Comparative Analysis of Ecological Drivers and Chemical Responses

Table 1: Ecological Drivers and Chemical Adaptation Strategies in Terrestrial vs. Marine Environments

| Factor | Terrestrial Environment | Marine Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Defense Challenges | Herbivory, pathogen infection, desiccation, UV exposure | Predation, space competition, fouling, microbial infection |

| Physical Mobility | Mostly mobile or wind-dispersed | Often sessile or slow-moving |

| Chemical Diversity Hotspots | Composite family (32,700+ species), Leguminosae (20,800+ species), Labiatae [12] | Sponges, cnidarians, tunicates, marine microorganisms [12] [16] |

| Representative Compound Classes | Terpenoids (limonene, tanshinone), alkaloids (morphine), flavonoids (quercetin, kaempferol) [12] | Nucleosides (spongothymidine, spongouridine), peptide toxins (ziconotide), polyketides (trabectedin) [12] [16] |

| Structural Characteristics | Higher oxygen content, more stereocenters, complex terpenoids [14] | More nitrogen and halogen atoms, lower solubility, higher molecular weight [14] |

| Bioactivity Profile | Broad-spectrum antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory [12] | Potent cytotoxic, anticancer, antiviral, ion channel modulation [16] |

The experimental data reveal how profoundly ecological pressures shape chemical innovation. Terrestrial plants, particularly dicotyledons (83.7% of plant natural products), have evolved complex terpenoid pathways as their dominant defense chemistry [12]. The high incidence of flavonoids in the Leguminosae family (approximately 50% of their compounds) exemplifies adaptation to terrestrial stressors like UV radiation and oxidative damage [12]. In contrast, marine organisms produce compounds with distinct structural features including more nitrogen and halogen atoms, and higher molecular weight compared to terrestrial natural products [14]. These differences reflect the marine environment's unique biosynthetic pathways and the need for compounds that remain effective in aqueous environments.

Experimental Protocols for Chemical Diversity Research

Metabolite Extraction and Isolation Workflows

The investigation of ecological chemical diversity requires sophisticated extraction and isolation protocols tailored to the distinct physicochemical properties of terrestrial versus marine metabolites. For terrestrial plant materials, the process typically begins with air-drying and grinding of plant tissues, followed by sequential solvent extraction using solvents of increasing polarity (hexane, ethyl acetate, methanol). The crude extracts are then fractionated using vacuum liquid chromatography or flash column chromatography, with subsequent purification steps employing techniques such as preparative thin-layer chromatography, medium-pressure liquid chromatography, and finally high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV/Vis detection [12].

Marine organism processing requires additional considerations due to the high water content and potential for compound degradation. Samples are typically flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection and maintained at -80°C until extraction. The process often involves freeze-drying followed by homogenization and sequential extraction with organic solvents. A critical difference in marine natural product isolation is the frequent need to address the "producer problem"—determining whether compounds originate from the macroscopic organism or its associated microbial symbionts [12]. This requires specialized approaches such as microbial cultivation, metagenomic analysis, and stable isotope feeding experiments.

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Chemical Characterization

Table 2: Analytical Techniques for Chemical Diversity Assessment

| Technique | Applications | Key Experimental Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrahigh-Resolution FTICR-MS | Comprehensive DOM chemodiversity assessment, molecular formula assignment [25] | 12 Tesla magnet, negative ion mode, mass range 100-900 m/z, resolution: 220K at m/z 481.185 [25] |

| Multidimensional NMR Spectroscopy | Structural elucidation, stereochemistry determination, mixture analysis | ¹H (400-900 MHz), ¹³C, COSY, HSQC, HMBC experiments; often requires specialized probes for limited samples |

| UHPLC-HRMS | Metabolite profiling, dereplication, quantitative analysis | C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7-1.8 μm), mobile phase: water/acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, ESI positive/negative switching |

| Biological Screening Assays | Target-based screening, phenotypic assessment, mechanism of action studies | Concentration range: 0.1-100 μM, positive controls included, assay replicates (n=3-6) [16] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction | Sample cleanup, fractionation, concentration of trace metabolites | C18, HLB, or mixed-mode sorbents; sequential elution with water-methanol or water-acetonitrile gradients [16] |

The molecular complexity of ecological metabolites demands sophisticated analytical technologies. The Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FTICR-MS) has emerged as particularly valuable for assessing chemodiversity, capable of detecting 2,500-8,718 unique molecular formulae in a single sample and revealing fundamental scaling patterns of chemical diversity with environmental characteristics [25]. For structure elucidation, advanced NMR techniques including COSY, HSQC, and HMBC are essential for determining complex stereochemistries frequently encountered in both terrestrial and marine natural products.

Biological screening strategies have evolved to include both target-based approaches (enzyme inhibition, receptor binding) and phenotypic assays (antiproliferative, antimicrobial). A critical consideration is the bioassay-guided fractionation approach, which links biological activity to specific compounds throughout the isolation process [16]. For marine samples, particular attention must be paid to compound stability and the potential for non-specific activity from salts or abundant proteins.

Visualization of Research Workflows

Diagram 1: Chemical Ecology Research Workflow. This diagram illustrates the integrated approach for discovering bioactive natural products from terrestrial and marine sources, highlighting the critical feedback loop of bioassay-guided fractionation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical Diversity Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Methanol, ethanol, acetonitrile, dichloromethane, hexane | Sequential extraction of metabolites based on polarity; methanol-water mixtures for polar compounds, dichloromethane for medium polarity [12] |

| Chromatography Media | C18 silica, Sephadex LH-20, Diaion HP-20, normal phase silica | Fractionation of complex extracts; C18 for reversed-phase separation, Sephadex for desalting and size separation [16] |

| NMR Solvents | Deuterated chloroform (CDCl3), deuterated methanol (CD3OD), deuterated water (D2O) | Solvent for structural elucidation; CDCl3 for non-polar compounds, CD3OD for polar compounds, D2O for water-soluble metabolites |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Sodium trifluoroacetate, Ultramark 1621, leucine enkephalin | Mass calibration for FTICR-MS and other MS instruments; ensures accurate mass measurement for elemental composition determination [25] |

| Bioassay Reagents | Resazurin (alamarBlue), MTT, caspase kits, antimicrobial test strains | Assessment of biological activity; resazurin/MTT for cell viability, specific strains for antimicrobial testing [16] |

| Chemical Derivatization Agents | BSTFA + TMCS, methoxyamine hydrochloride, dansyl chloride | Chemical modification for GC-MS analysis or detection enhancement; BSTFA for silylation of polar compounds for GC-MS [25] |

The selection of appropriate research reagents is critical for successful chemical diversity studies. For marine natural products research, the presence of salts can interfere with both chemical analysis and bioassays, making desalting steps using resins like Sephadex LH-20 particularly important [16]. Similarly, the tendency of some marine compounds to degrade under standard laboratory conditions necessitates the inclusion of antioxidant additives such as BHT or ascorbic acid in extraction protocols. For terrestrial plant studies, the high abundance of tannins and polyphenols can create false positives in bioassays, requiring removal through polyamide chromatography or PVPP treatment.

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

The ecological drivers of chemical diversity have direct consequences for pharmaceutical development. Marine-derived compounds have yielded clinically approved drugs including ziconotide (Prialt) for severe pain and trabectedin (Yondelis) for soft-tissue sarcoma, with many more in clinical trials [12] [16]. These successes underscore the potential of marine chemical defense strategies as sources of novel therapeutics, particularly for challenging targets like cancer and neuropathic pain.

Terrestrial plant-derived compounds continue to provide valuable drug leads, with notable examples including morphine from opium poppy and paclitaxel from Pacific yew tree [12]. The broad-spectrum bioactivity of plant secondary metabolites aligns with their ecological roles as multi-purpose defense compounds, which can be advantageous for drug discovery but may also increase the risk of off-target effects.

From a technical perspective, marine natural products present specific challenges for drug development, including limited availability from original sources, complex synthesis pathways, and sometimes unfavorable physicochemical properties [16]. These hurdles are being addressed through advanced aquaculture, microbial fermentation, and synthetic biology approaches. Terrestrial plant products face challenges related to seasonal variability and sustainable sourcing, which are increasingly being overcome through cell culture techniques and metabolic engineering.

The comparative analysis of terrestrial and marine chemical defense strategies reveals how profoundly ecological pressures shape nature's molecular innovation. Terrestrial plants have evolved complex chemical arsenals dominated by terpenoids and flavonoids to counter herbivory, pathogen attack, and environmental stressors. Marine organisms, particularly sessile invertebrates, have developed structurally distinct compounds rich in nitrogen and halogens as their primary defense in a highly competitive aqueous environment.

For drug discovery professionals, this ecological understanding provides valuable guidance for bioprospecting strategies. The continued exploration of both terrestrial and marine chemical diversity, supported by advancing analytical technologies and research methodologies, promises to deliver novel therapeutic agents while revealing fundamental insights into nature's chemical language of survival and adaptation.

From Source to Screen: Methodological Approaches and Therapeutic Applications in Natural Product Research

Modern Extraction and Isolation Techniques for Complex Metabolites

The quest for novel bioactive compounds has expanded into the chemically distinct worlds of terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Marine natural products (MNPs) and terrestrial natural products (TNPs) differ fundamentally in their physicochemical properties, necessitating tailored approaches for their extraction and isolation [7]. Research indicates that MNPs generally possess lower solubility and larger molecular sizes than their terrestrial counterparts [7]. Structurally, MNPs more frequently incorporate nitrogen atoms and halogens (particularly bromine), utilize more long chains and large rings (especially 8- to 10-membered rings), and are biosynthesized through more diverse pathways [7]. These structural differences directly influence extraction strategy selection, solvent compatibility, and downstream processing requirements.

The market for natural product research reflects this divergence, with the marine natural products market projected to grow from $10.1 billion in 2025 to $21.5 billion by 2033, demonstrating increasing research and commercial interest in marine-derived compounds [26]. This growth is paralleled in specific technical sectors, with the cell-free DNA isolation and extraction market expected to reach $2.66 billion by 2029, underscoring the expanding role of molecular extraction technologies in life sciences research [27]. This article provides a comparative guide to modern extraction methodologies, enabling researchers to systematically approach the challenges presented by these chemically complex metabolites from different biological origins.

Comparative Analysis of Extraction Method Performance

Selecting the optimal extraction method requires balancing multiple performance parameters, including metabolite coverage, recovery efficiency, matrix effects, and technical repeatability. The following analysis synthesizes data from systematic evaluations of common extraction techniques.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Extraction Methods for Metabolite Analysis [28]

| Extraction Method | Metabolite Coverage | Recovery Efficiency | Matrix Effects | Method Repeatability | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol Precipitation | Broadest coverage | High for polar metabolites | High susceptibility | Excellent precision | Global untargeted profiling of polar metabolites |

| Methanol/Ethanol Precipitation | Broad coverage | High for polar metabolites | High susceptibility | Excellent precision | Routine global metabolomics |

| Methanol/MTBE Precipitation | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Good precision | Balanced polar/lipid metabolite extraction |

| MTBE Liquid-Liquid Extraction | Dual-phase coverage | Good for both polar/lipid | Moderate susceptibility | Good precision | Simultaneous polar/lipid metabolome |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction | Selective | Variable (compound-dependent) | Reduced phospholipids | Good repeatability | Targeted analysis, phospholipid removal |

| Ion-Exchange SPE | Complementary to methanol | Variable (charge-dependent) | Reduced | Good repeatability | Acidic/basic metabolite fractionation |

| PEP2 SPE | Moderate | High for non-polar | Reduced | Good repeatability | Non-polar metabolite enrichment |

Key Performance Insights

Solvent precipitation methods (methanol, methanol/ethanol) provide the widest metabolite coverage and excellent technical repeatability, making them ideal for initial untargeted profiling workflows. However, this comprehensive coverage comes with a significant drawback: high susceptibility to matrix effects that can suppress ionization of lower-abundance metabolites in mass spectrometry analysis [28].

Orthogonality in extraction is critical for expanding metabolome coverage. Research demonstrates that using multiple, complementary extraction methods can increase metabolite detection by 34-80% compared to single-method approaches, despite the increased analytical time and sample requirements [28]. The most orthogonal methods to standard methanol precipitation are ion-exchange solid-phase extraction and methyl-tertbutyl ether liquid-liquid extraction [28].

Solid-phase extraction techniques offer advantages in specific applications through selective metabolite retention. These methods typically demonstrate reduced matrix effects and improved repeatability for target metabolite classes, though at the cost of overall coverage [28]. For example, optimized HybridSPE methods effectively remove phospholipids to minimize ion suppression while maintaining acceptable recovery rates [28].

Experimental Protocols for Metabolite Extraction

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Metabolite Extraction via Methanol Precipitation

Principle: This method utilizes cold organic solvents to simultaneously precipitate proteins and extract a wide range of metabolites, maximizing coverage for untargeted analysis [28] [29].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Combine 100 µL of plasma (or tissue homogenate) with 300 µL of cold methanol (-20°C) [28].

- Protein Precipitation: Vortex vigorously for 30 seconds and incubate at -20°C for 60 minutes.

- Pellet Separation: Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Supernatant Collection: Transfer the supernatant to a clean tube without disturbing the protein pellet.

- Solvent Evaporation: Dry the extract under a gentle nitrogen stream or using a vacuum concentrator.

- Sample Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried metabolites in 100 µL of reconstitution solvent (e.g., water/methanol, 95:5) compatible with subsequent LC-MS analysis.

- Quality Control: Analyze using LC-MS with pooled quality control samples.

Optimization Notes: The plasma-to-solvent ratio is critical; a 1:3 ratio is standard, but 1:4 may improve recovery for some metabolite classes. Maintaining samples at low temperatures throughout the process minimizes metabolite degradation and enzymatic activity [28].

Protocol 2: Sequential Extraction of Polar and Lipophilic Metabolites with MTBE

Principle: This liquid-liquid extraction method partitions metabolites according to polarity, providing fractions enriched in polar (aqueous) and lipophilic (organic) compounds [28].

Procedure:

- Initial Mixture: To 100 µL of sample, add 300 µL of methanol and 1 mL of methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE).

- Phase Separation: Vortex for 30 seconds, then centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes to achieve clear phase separation.

- Organic Phase Collection: Carefully transfer the upper organic phase (MTBE layer) containing lipophilic metabolites to a new tube.

- Aqueous Phase Collection: Collect the lower aqueous phase (methanol/water layer) containing polar metabolites.

- Interface Wash: Retain the protein pellet at the interface for potential proteomics analysis.

- Drying and Reconstitution: Separately dry both fractions under nitrogen and reconstitute in appropriate solvents for analysis.

Optimization Notes: This method provides good coverage of both polar and lipid metabolomes and is particularly valuable when sample volume is limited, as it generates two analytically useful fractions from a single extraction [28].

Protocol 3: Selective Fractionation Using Mixed-Mode Solid-Phase Extraction

Principle: Mixed-mode sorbents containing both reversed-phase and ion-exchange functionalities separate metabolites based on both hydrophobicity and charge [28].

Procedure:

- Sorbent Conditioning: Sequentially condition the SPE cartridge with methanol and water.

- Sample Loading: Apply the sample (preferably in a weak solvent) to the cartridge.

- Wash Steps:

- Wash with water to remove neutral and polar compounds.

- Wash with a solvent of low ionic strength to remove interfering compounds while retaining analytes.

- Sequential Elution:

- Elute acidic metabolites with a basic organic solvent.

- Elute neutral metabolites with an intermediate-polarity solvent.

- Elute basic metabolites with an acidic organic solvent.

- Fraction Analysis: Collect all fractions separately, evaporate solvents, and reconstitute for LC-MS analysis.

Optimization Notes: Mixed-mode SPE offers enhanced selectivity compared to single-mechanism sorbents and can significantly reduce matrix effects by separating metabolite classes into distinct fractions [28].

Workflow Visualization

Graph 1: Metabolite Extraction and Analysis Workflow. The workflow begins with sample selection, followed by strategic method choice based on research objectives, proceeding through extraction, instrumental analysis, and final data processing.

Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolite Extraction

Successful metabolite extraction requires specific reagents and materials optimized for different sample types and metabolite classes. The following table details essential components of the extraction toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolite Extraction Protocols

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol (LC-MS Grade) | Protein precipitation; extraction of polar metabolites | Primary solvent for precipitation methods; cold (-20°C) for improved protein denaturation [28] |

| Methyl-tert-butyl Ether (MTBE) | Liquid-liquid extraction; lipid fraction isolation | Paired with methanol for simultaneous polar/lipid extraction [28] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Sorbents | Selective metabolite fractionation | C18 (reversed-phase), Ion-Exchange (IEX), Divinylbenzene-pyrrolidone (PEP2) [28] |

| Magnetic Beads | Automated nucleic acid isolation | Surface-functionalized for DNA/RNA binding; enable high-throughput automation [27] [30] |

| Silica Membranes/Columns | Nucleic acid binding and purification | Column-based isolation of cell-free DNA; commonly used in kits [27] |

| Enzymes for Cell Lysis | Cellular disruption for metabolite release | Lysozyme (bacterial walls), cellulase (plant cells), zymolase (fungal cells) [29] |

| Stabilization Buffers | Prevent metabolite degradation during processing | RNAlater for RNA; specific additives for labile metabolites [27] |

Technology and Market Trends

The landscape of extraction technologies is evolving rapidly, with several key trends influencing reagent and kit development:

Automation and high-throughput systems are becoming standard, with leading companies introducing products like the MagBench Automated DNA Extraction Instrument that streamline workflows and improve reproducibility [27]. Magnetic bead-based technologies dominate automated platforms due to their compatibility with liquid handling systems and consistent performance [30].

Kit specialization continues to advance, with product launches targeting specific applications such as the Monarch Mag Viral DNA/RNA Extraction Kit for pathogen detection and dual-phase extraction systems that enable simultaneous RNA and DNA purification from a single sample [30].

Sustainability considerations are driving development of eco-friendly extraction methods that reduce organic solvent consumption and utilize greener alternatives, particularly important for large-scale natural products extraction [26] [29].

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that no single extraction method universally outperforms others across all metabolite classes and sample types. The optimal approach depends critically on the biological source (terrestrial vs. marine), target metabolite properties, and research objectives (untargeted vs. targeted). Method selection requires careful consideration of the inherent chemical differences between terrestrial and marine natural products, particularly their distinct halogenation patterns, ring systems, and solubility characteristics [7].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on increasing orthogonality through sequential extraction approaches, enhancing automation for improved reproducibility, and incorporating sustainability principles into extraction design. As the marine natural products market continues its robust growth [26] and molecular extraction technologies advance [27] [30], researchers will benefit from increasingly sophisticated tools to access the chemical diversity offered by both terrestrial and marine organisms. Through strategic method selection and optimization based on the principles outlined in this guide, researchers can significantly enhance their capability to discover novel bioactive compounds from nature's chemical repertoire.

The discovery and development of bioactive compounds from natural sources rely heavily on a suite of advanced analytical techniques. Researchers employ these methods to isolate, identify, characterize, and evaluate compounds with potential therapeutic value. Within the specific context of comparing terrestrial and marine natural products, the selection of appropriate screening methods is critical, as these two domains often produce compounds with distinct physicochemical properties. Marine natural products (MNPs) frequently possess unique structural features, including more nitrogen atoms and halogens (particularly bromine), more long chains and large rings (especially 8- to 10-membered rings), and fewer oxygen atoms compared to terrestrial natural products (TNPs) [7]. These differences not only influence their biological activity but also dictate the optimal approach for their analysis. This guide provides a comparative analysis of four cornerstone techniques—UV/VIS spectroscopy, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and Biological Assays—objectively evaluating their performance in profiling natural products within a comparative terrestrial versus marine research framework.

Core Techniques: Principles and Comparative Performance

Each analytical technique provides a unique piece of the puzzle in natural product characterization. The following section details the principles, applications, and relative strengths and weaknesses of UV/VIS, MS, NMR, and biological assays.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV/VIS) Spectroscopy

Principles and Applications: UV/VIS spectroscopy measures the absorption of ultraviolet or visible light by a sample, resulting from electronic transitions of molecules. When a molecule absorbs a photon, an electron is promoted from a ground state to an excited state. The absorbance is quantitatively described by the Beer-Lambert Law (A = ε × c × d, where A is absorbance, ε is molar absorptivity, c is concentration, and d is path length) [31]. In natural products research, it is widely used for quantifying the concentration of nucleic acids (at 260 nm) and proteins (at 280 nm), assessing purity, and monitoring reaction kinetics [32] [31]. Its utility in distinguishing between complex samples has been demonstrated in fields like food authenticity and, more recently, in discriminating between recycled and virgin plastics by analyzing chromophores in sample extracts [33].

Advantages and Limitations: The primary advantages of UV/VIS spectroscopy are its simplicity, rapid analysis, cost-effectiveness, and high sensitivity for compounds with chromophores [31]. However, its major limitation is that it provides limited structural information and is generally restricted to compounds that undergo electronic transitions in the UV-VIS range, making it less effective for colorless samples or those lacking conjugation [31].

Mass Spectrometry (MS)

Principles and Applications: MS measures the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions to identify and quantify molecules in a sample. It is a cornerstone technique for determining molecular weight and elucidating structural fragments. When coupled with separation techniques like gas chromatography (GC) or liquid chromatography (LC), it becomes a powerful tool for analyzing complex mixtures [34] [31]. In metabolomics studies, GC-MS is routinely employed, having identified 82 metabolites in a study on Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, 16 of which were unique to the technique and not detected by NMR [34]. Its high sensitivity and dynamic range make it indispensable for detecting low-abundance metabolites.

Advantages and Limitations: MS offers high sensitivity, a wide dynamic range, and the ability to analyze extremely complex mixtures [34] [31]. A key limitation is that it can require extensive sample preparation and chromatography to reduce matrix effects, and it may fail to detect metabolites that are not readily ionizable [34]. Ambiguous peak assignments can also occur without robust reference libraries [34].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

Principles and Applications: NMR spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei (e.g., 1H, 13C) to provide detailed information on molecular structure, dynamics, and environment. It is unparalleled in elucidating the planar connectivity and stereochemistry of organic molecules [34] [31]. In the aforementioned metabolomics study, NMR uniquely identified 20 metabolites, providing critical coverage of metabolic pathways that informed on central carbon metabolism [34]. NMR is particularly valuable for identifying isomeric compounds and providing quantitative data without the need for calibration curves.

Advantages and Limitations: The key advantage of NMR is its ability to provide definitive structural information, including stereochemistry, in a non-destructive manner with minimal sample handling [34]. Its main drawbacks are lower sensitivity compared to MS (typically requiring micromolar concentrations), limited spectral resolution that can lead to peak overlap in complex mixtures, and relatively high sample concentration requirements [34].

Biological Assays

Principles and Applications: Biological assays are not a single spectroscopic technique but a broad category of tests used to evaluate the functional effects of a compound in a biological system. These range from simple antimicrobial disk diffusion assays and enzyme inhibition tests to complex cell-based assays measuring cytotoxicity, antiviral activity, or wound healing [35]. For instance, the therapeutic potential of synthetic 4-aminocoumarin derivatives was evaluated through a battery of biological assays testing their antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and wound-healing properties [35]. These assays are essential for bridging the gap between compound identification and therapeutic application.

Advantages and Limitations: The primary advantage of biological assays is that they provide direct evidence of bioactivity and potential therapeutic utility. However, they can be time-consuming, low-throughput, and their results are often complex to interpret due to the interplay of multiple biological variables.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Key Spectroscopic and Biological Techniques in Natural Product Analysis.

| Technique | Primary Information Obtained | Sensitivity | Sample Throughput | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV/VIS Spectroscopy | Electronic transitions; concentration | High (for chromophores) | High | Rapid, simple, cost-effective, excellent for quantification | Limited structural info, requires a chromophore |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Molecular mass; structural fragments | Very High (sub-μM) | Medium-High (with chromatography) | Excellent sensitivity; works with complex mixtures; hyphenation possible | Ion suppression; may need derivatization; not inherently quantitative |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Molecular structure; atomic connectivity | Low-Medium (≥1 μM) | Low-Medium | Definitive structural & stereochemical info; non-destructive; quantitative | Lower sensitivity; requires high concentration; complex data analysis |

| Biological Assays | Bioactivity; therapeutic potential | Varies by assay | Low (often) | Provides functional, pharmacologically relevant data | Time-consuming; complex; results can be organism-dependent |

Experimental Protocols for Technique Application

Protocol: Combined NMR and MS for Metabolomics

This protocol is adapted from a study highlighting the complementarity of NMR and MS for comprehensive metabolome coverage [34].

- Sample Preparation: Cells (e.g., Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) are grown in media containing 13C2-acetate for NMR isotopic labeling. Metabolites are extracted using an aqueous solvent system.

- NMR Analysis:

- Instrumentation: A high-field NMR spectrometer (e.g., 600 MHz).

- Data Acquisition: Collect 1D 1H NMR and 2D 1H-13C HSQC spectra.

- Processing: Process data using software like NMRpipe. Apply standard normal variate (SNV) normalization and unit variance scaling.

- Metabolite Assignment: Perform peak picking and metabolite assignment using databases such as the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB).

- GC-MS Analysis:

- Sample Derivatization: Derivatize aliquots of the same extract to make metabolites volatile for GC.

- Instrumentation: Use a GC-MS system.

- Data Acquisition: Inject samples and acquire mass spectra.

- Data Processing: Use software packages (e.g., eRah) for peak picking, retention time alignment, and metabolite library searching against databases like GOLM.

- Data Integration: Combine the assigned metabolite lists from NMR and MS. Use statistical tools like Multiblock PCA (MB-PCA) to generate a single model that integrates both datasets for a unified analysis.

Protocol: Biological Profiling of Synthetic Derivatives

This protocol outlines a multi-faceted approach to evaluate the therapeutic potential of new compounds, as demonstrated in a study on 4-aminocoumarin derivatives [35].

- Structural Validation:

- Characterize synthesized compounds using UV-Vis, FT-IR, GC-MS, 1H-NMR, and 13C-NMR to confirm structure and purity.

- In Vitro Antibacterial/Antifungal Assay:

- Test compounds against a panel of bacterial and fungal strains.

- Determine Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC₉₀) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) values using standard broth microdilution methods. Compare to standard antibiotics like ciprofloxacin.

- Cytotoxicity Assay:

- Assess cytotoxicity on relevant human cell lines (e.g., human epidermal keratinocyte cells).

- Use the MTT assay at a range of concentrations (e.g., 1–100 µg/mL) to measure cell viability after exposure.

- Antiviral Assay:

- Evaluate compounds against viruses (e.g., Dengue virus type-2).

- Infect host cells (e.g., BHK-21 cells) in the presence of non-toxic compound concentrations and measure the reduction in cytopathic effect.

- In Silico Studies:

- Perform ADME/Tox (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) prediction and molecular docking studies to understand the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of the lead compounds.

Application in Terrestrial vs. Marine Natural Products Research

The distinct chemical landscapes of terrestrial and marine environments necessitate a tailored analytical approach. Marine natural products often present specific challenges, such as complex stereochemistry and the presence of unique halogens like bromine, which can lead to a higher rate of structural misassignments [7] [36].

Statistical analysis of structural revisions between 2005 and 2010 reveals that misassignments in marine natural products are more frequently related to configuration (67%) than constitution (33%) [36]. The data shows that the techniques most commonly associated with these misassignments are NOE data (26% of marine misassignments), general NMR comparison, and HMBC data [36]. This underscores the critical need for orthogonal verification, often through total synthesis, to confirm the structures of complex marine molecules [36].

Table 2: Analysis of Techniques Involved in Marine Natural Product Structural Misassignments (2005-2010).

| Technique Used in Initial Misassignment | Percentage of Total Marine Misassignments | Type of Error Most Associated |

|---|---|---|

| NOE Data | 26% | Configurational |

| NMR Comparison | Significant (exact % not specified) | Configurational & Constitutional |

| HMBC & other NMR | Significant (exact % not specified) | Constitutional |

When profiling extracts, a combined NMR and MS approach is particularly powerful. A comparative study demonstrated that while GC-MS identified a larger number of unique metabolites (16), NMR was able to identify a different set of unique metabolites (14), with 17 metabolites identified by both techniques [34]. This synergy greatly enhanced the coverage of central metabolic pathways. For marine-specific analysis, where novel scaffolds are common, the definitive structural power of NMR is indispensable, while the sensitivity of MS is crucial for detecting minor, yet potentially bioactive, components.

Diagram 1: A typical workflow integrating multiple techniques for the isolation and identification of bioactive natural products.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful analysis requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items essential for experiments in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Screening.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O, CD₃OD) | Provides an NMR-inert solvent for analyzing samples in NMR spectroscopy. | Used in the preparation of samples for 1H and 13C NMR analysis [34]. |

| Deuterium & Tungsten/Halogen Lamps | Serve as stable light sources for the UV and visible ranges, respectively, in UV/VIS spectrophotometers. | A core component of the instrumentation for measuring electronic transitions [32] [31]. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemically modify metabolites to make them volatile and stable for GC-MS analysis. | Used in the GC-MS metabolomics protocol for the analysis of organic acids and amino acids [34]. |

| Chromatography Columns (HPLC, UPLC) | Separate complex mixtures into individual components prior to introduction into the mass spectrometer. | Essential for UPLC-Q-TOF-MS analysis to resolve non-volatile compounds from complex samples like recycled plastics [33]. |

| Cell Lines & Culture Media | Provide the biological system for in vitro assays to determine cytotoxicity, antiviral, or other pharmacological activities. | Used in cytotoxicity (e.g., human keratinocytes) and antiviral (e.g., BHK-21) assays [35]. |

| Specific Chemical Standards | Pure compounds used for calibration, quantification, and as references for structural identification. | Critical for confirming the identity of metabolites via comparison of retention times (MS) and chemical shifts (NMR) [34]. |

Diagram 2: Analytical challenges and solutions specific to terrestrial versus marine natural products.

No single analytical technique is sufficient for the comprehensive study of terrestrial and marine natural products. UV/VIS spectroscopy offers rapid quantification, MS provides unparalleled sensitivity for detection, NMR delivers definitive structural elucidation, and biological assays reveal crucial functional activity. The inherent complementarity of these methods is well-established; for example, combining NMR and MS significantly expands metabolome coverage and increases confidence in metabolite identification [34]. This integrated approach is especially critical for navigating the unique structural challenges posed by marine natural products, helping to minimize misassignments and fully leverage the vast potential of the world's oceans and terrestrial ecosystems for drug discovery.

Lead Compound Identification and Mechanism of Action Studies

The identification of lead compounds from natural products (NPs) represents a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, with terrestrial and marine environments offering distinct and complementary reservoirs of chemical diversity [12] [16]. Terrestrial NPs, primarily derived from plants, have historically been the most prolific source of medicines; approximately 70% of recorded NPs in the Dictionary of Natural Products are of plant origin, with key families like Compositae, Leguminosae, and Labiatae contributing significantly [12]. In contrast, marine NPs, sourced from organisms such as sponges, tunicates, and soft corals, inhabit an environment characterized by extreme variations in pressure, salinity, and temperature, which has driven the evolution of unique and potent bioactive metabolites [16]. Since the discovery of the first marine NPs, spongothymidine and spongouridine, from the sponge Tectitethya crypta in the early 1950s, over 39,500 marine natural products with potent biological activities have been identified [12] [16]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the methodologies and challenges inherent in identifying lead compounds and elucidating their mechanisms of action (MOA) from these two vast and critically important sources.

Comparative Structural and Physicochemical Properties

The structural and physicochemical properties of natural products directly influence their suitability as lead compounds, affecting aspects like solubility, bioavailability, and target interaction. A comparative analysis reveals fundamental differences between terrestrial natural products (TNPs) and marine natural products (MNPs), shaped by their distinct evolutionary environments and biosynthetic pathways [7].

Table 1: Comparative Physicochemical Properties of Terrestrial and Marine Natural Products

| Property | Terrestrial Natural Products (TNPs) | Marine Natural Products (MNPs) |

|---|---|---|

| General Solubility | Higher | Lower [7] |

| Average Molecular Size | Generally smaller | Larger, more bulky [7] |

| Prevalent Rings | More stable ring systems; common 5- and 6-membered rings [14] | More long chains and large rings (e.g., 8- to 10-membered rings) [7] |

| Nitrogen (N) Atoms | Fewer | More [7] |

| Oxygen (O) Atoms | More | Fewer [7] |

| Halogen Atoms | Fewer | More, notably bromines [7] |

| Key Fragments/Scaffolds | Shorter scaffolds; higher proportion of terpenoids and flavonoids [12] | Longer scaffolds often containing ester bonds connected to large rings [7] |

| Structural Complexity | High, with increasing glycosylation over time [14] | High, with more long chains and large rings [7] |

Marine NPs generally possess lower solubility and are often larger than their terrestrial counterparts [7]. From a structural perspective, MNPs frequently feature more long chains and large rings, particularly 8- to 10-membered rings, whereas TNPs tend to incorporate more stable ring systems, with 5- and 6-membered rings being common [7]. Elemental composition also differs significantly; MNPs typically contain more nitrogen atoms and halogens (notably bromines) and fewer oxygen atoms, suggesting they are synthesized by more diverse biosynthetic pathways [7]. The analysis of Murcko frameworks reveals that MNP scaffolds tend to be longer and often contain ester bonds connected to 10-membered rings, while TNP scaffolds are generally shorter and bear more stable ring systems and bond types [7]. These inherent structural differences necessitate tailored approaches for the isolation, characterization, and development of lead compounds from each source.

Experimental Workflows for Lead Identification and Mechanism Elucidation

The journey from a raw biological sample to a understood lead compound involves a multi-stage process. While the overall workflow is similar for both terrestrial and marine sources, specific techniques and challenges vary at each stage. The following diagram illustrates the generalized pathway for identifying lead natural products and studying their mechanism of action.

Sample Preparation and Bioassay-Guided Fractionation

The initial stage involves preparing the sample for analysis. For both plant and marine organisms, this begins with extraction using solvents of varying polarity (e.g., methanol, dichloromethane) to obtain a crude extract [16]. The extract is then subjected to a series of chromatographic separation techniques—such as solid-phase extraction, thin-layer chromatography (TLC), and vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC)—to generate fractions of reduced complexity [16].