Target Identification and Validation for Natural Products: Advanced Strategies for Unlocking Nature's Pharmacy

Target identification and validation are critical, foundational steps in modern natural product-based drug discovery, transforming traditional remedies into targeted therapeutics with understood mechanisms of action.

Target Identification and Validation for Natural Products: Advanced Strategies for Unlocking Nature's Pharmacy

Abstract

Target identification and validation are critical, foundational steps in modern natural product-based drug discovery, transforming traditional remedies into targeted therapeutics with understood mechanisms of action. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the fundamental importance of target discovery, detailing cutting-edge methodological approaches from chemical proteomics to label-free strategies, and addressing key challenges in the field. It further outlines rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of emerging technologies, synthesizing the latest 2025 research to offer a practical roadmap for elucidating the pharmacological mechanisms of natural products and accelerating their path to clinical application.

Why Target Discovery is the Cornerstone of Natural Product Drug Development

The Critical Role of Target Identification in De-risking Drug Discovery

Target identification and validation represent the critical first step in the modern drug discovery pipeline, serving as the primary defense against costly late-stage failures. This process aims to pinpoint biological molecules—such as proteins, genes, or RNA—that play a key role in disease progression and can be modulated by therapeutic intervention [1]. The profound importance of this initial stage cannot be overstated; target identification fundamentally determines the trajectory of all subsequent development efforts, with inaccurate target selection virtually guaranteeing clinical failure despite perfect execution in later stages [2] [3]. The high stakes are reflected in development statistics: between 2013 and 2022, the median cost for new drug development rose to approximately $2.4 billion, while development timelines extended by one to two years, underscoring the immense economic imperative of improving early-stage decision-making [1].

The challenges inherent to target identification are particularly pronounced for natural products, which often demonstrate compelling biological activity but whose mechanisms of action remain elusive due to complex pharmacological profiles and technical limitations in identifying their molecular interactors [4]. For these compounds, classical affinity purification strategies—which rely on specific physical interactions between ligands and their targets—have been complemented by advanced techniques including click chemistry, photoaffinity labeling, and cellular phenotypic screening [4]. Meanwhile, computational approaches have emerged as powerful tools for generating testable hypotheses about potential drug-target interactions, offering the potential to prioritize experimental efforts and accelerate the validation process [5] [2].

This guide provides a systematic comparison of contemporary target identification methods, with particular emphasis on their application to natural products research. By objectively evaluating performance metrics, experimental requirements, and practical considerations, we aim to equip researchers with the evidence needed to select optimal strategies for de-risking their drug discovery pipelines from the very beginning.

Comparative Analysis of Target Identification Methods

Methodologies and Performance Benchmarks

Target identification strategies generally fall into two primary categories: experimental approaches that directly probe physical interactions between compounds and their cellular targets, and computational approaches that predict interactions based on chemical structure, omics data, or biological network information. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of established and emerging methods, highlighting their respective strengths and limitations for natural product research.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Target Identification Methods

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Requirements | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Ligand-Centric | MolTarPred, PPB2, SuperPred | MolTarPred identified as most effective in systematic comparison; recall reduced with high-confidence filtering [5] | Stand-alone codes or web servers; chemical structures as input | Fast, low-cost; suitable for novel compounds without known targets | Limited by known ligand-target annotations in databases |

| Computational Target-Centric | RF-QSAR, TargetNet, CMTNN | Varies by algorithm; CMTNN uses ChEMBL 34 and ONNX runtime [5] | Protein structures or target bioactivity data | Can predict novel target space; structure-based insights | Limited by protein structure availability and quality |

| AI and Machine Learning | PandaOmics, Chemistry42, DNABERT, ESMFold | Identified CDK20 as novel target for HCC; generated inhibitor with IC50 = 33.4 nmol/L [1] | Multi-omics data, chemical structures, or biological text | High-dimensional pattern recognition; rapid hypothesis generation | "Black box" limitations; requires large, high-quality datasets |

| Experimental Affinity-Based | Affinity purification, target fishing | Direct physical validation of compound-target interactions [4] | Functionalized compounds, cell lysates, mass spectrometry | Direct experimental evidence; no prior knowledge required | Requires compound modification; may miss weak interactions |

| Advanced Chemical Biology | Click chemistry, photoaffinity labeling | Enabled identification of >50 natural product targets in recent years [4] | Chemical probes, UV irradiation equipment, proteomics | Captures transient interactions; high spatial-temporal resolution | Complex probe synthesis; potential for non-specific binding |

| Multi-Omics Integration | Network propagation, graph neural networks | Improved prediction accuracy by integrating >2 omics layers [6] | Multiple omics datasets, computational infrastructure | Systems-level insights; captures biological complexity | Data heterogeneity; computational intensity |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Computational Target Prediction Using MolTarPred

Objective: To predict potential protein targets for a query small molecule based on chemical similarity to compounds with known target annotations.

Workflow:

- Database Preparation: Host the ChEMBL database (version 34 recommended) locally. Retrieve and filter bioactivity records, keeping only those with standard values (IC50, Ki, or EC50) below 10,000 nM. Exclude non-specific or multi-protein targets and remove duplicate compound-target pairs to ensure data quality [5].

- Query Processing: Input the canonical SMILES string of the query molecule. Generate molecular fingerprints (Morgan fingerprints with radius 2 and 2048 bits are recommended over MACCS based on superior performance [5]).

- Similarity Calculation: Calculate Tanimoto similarity scores between the query fingerprint and all compounds in the database.

- Target Prediction: Rank database compounds by similarity score. The targets of the top similar compounds (e.g., top 1, 5, 10, and 15) are retrieved as potential targets for the query molecule.

- Validation: To prevent bias, ensure query molecules (e.g., FDA-approved drugs for validation) are excluded from the main database before prediction [5].

Figure 1: Computational target prediction workflow using MolTarPred methodology.

Affinity Purification for Natural Product Target Identification

Objective: To experimentally identify direct cellular targets of a natural product compound using affinity-based purification.

Workflow:

- Probe Design: Chemically modify the natural product to incorporate a functional handle (e.g., alkyne, azide, or biotin) while preserving its biological activity. This creates an affinity probe [4].

- Cell Treatment: Incubate the affinity probe with live cells or cell lysates under physiological conditions to allow binding to endogenous target proteins.

- Capture: Lyse cells and incubate the lysate with streptavidin or appropriate capture beads to immobilize the probe-target complexes.

- Washing: Thoroughly wash the beads with buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the bound proteins using competitive elution (e.g., with free natural product) or by boiling in SDS-PAGE buffer.

- Identification: Analyze the eluted proteins by mass spectrometry to identify the specific target proteins [4].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for affinity-based target identification of natural products.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful target identification requires specialized reagents and tools that enable precise molecular interrogation. The following table details essential solutions for both computational and experimental approaches.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Target Identification

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | Provides annotated compound-target interactions for ligand-centric prediction [5] |

| Affinity Probes | Chemically modified natural products with functional handles (biotin, alkyne) | Enable capture and isolation of target proteins from complex biological mixtures [4] |

| Photoaffinity Labels | Probes incorporating photoactivatable groups (e.g., diazirines) | Capture transient or weak protein-ligand interactions upon UV irradiation [4] |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Method for detecting target engagement in intact cells | Validates direct compound-target binding in physiologically relevant environments [7] |

| PandaOmics AI Platform | AI-powered target discovery platform | Integrates multi-omics data and literature mining for hypothesis generation [1] |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Repository of AI-predicted protein structures | Enables structure-based target prediction when experimental structures are unavailable [2] |

| CRISPR Screening Libraries | Tool for genome-wide functional screens | Identifies essential genes and synthetic lethal interactions for target validation [8] |

Integrated Workflows for Enhanced Confidence

The most robust target identification strategies combine multiple complementary approaches to overcome the limitations of individual methods. For natural products, a convergent workflow that integrates computational predictions with experimental validation has proven particularly effective [4] [6].

Computational methods provide valuable starting hypotheses by leveraging the growing wealth of chemical and biological data. For example, MolTarPred's ligand-centric approach can rapidly identify potential targets based on chemical similarity, while AI platforms like PandaOmics can integrate multi-omics data to prioritize targets within disease-relevant pathways [5] [1]. These computational predictions can then guide experimental design, focusing effort on the most promising candidates.

Experimental approaches remain essential for definitive validation, with affinity purification and related chemical biology techniques providing direct physical evidence of compound-target interactions [4]. The integration of cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) further strengthens validation by confirming target engagement in physiologically relevant environments [7]. This multi-layered strategy—combining computational efficiency with experimental rigor—creates a powerful framework for de-risking the early stages of drug discovery, particularly for mechanistically complex natural products.

Target identification represents both a formidable challenge and a tremendous opportunity in modern drug discovery. As the field advances, the integration of computational predictions with experimental validation creates a powerful framework for de-risking the early stages of drug development. For natural products research, this integrated approach is particularly valuable, helping to elucidate complex mechanisms of action that have long remained mysterious [4].

The evolving landscape of target identification is increasingly characterized by multidisciplinary integration, with AI and machine learning approaches working in concert with traditional experimental methods [2] [6] [1]. This convergence enables researchers to leverage the scalability of computational prediction while maintaining the empirical rigor of experimental validation. Furthermore, the growing emphasis on understanding polypharmacology—rather than single-target effects—acknowledges the complex biological reality that underpins both therapeutic efficacy and safety concerns [5].

By strategically implementing the comparative methodologies outlined in this guide, researchers can build a more robust, evidence-based foundation for their drug discovery programs. This systematic approach to target identification and validation ultimately reduces late-stage attrition rates, accelerates development timelines, and increases the probability of delivering effective therapeutics to patients.

For decades, the discovery of therapeutic targets for natural products (NPs) relied heavily on serendipitous findings—a slow, unpredictable process that created significant bottlenecks in drug development. The complex molecular structures of NPs and their multifaceted interactions within biological systems often obscured their precise mechanisms of action. Historically, this target ambiguity substantially impeded the transition of promising NPs from traditional remedies to modern pharmaceutical agents [9]. Today, however, the field is undergoing a profound transformation. A new era of systematic discovery is emerging, driven by innovative technological platforms that are decoding the molecular mysteries of NPs with unprecedented precision and efficiency. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these modern target identification strategies, equipping researchers with the data and methodologies needed to navigate this evolving landscape.

Methodological Comparison: Modern Target Identification Platforms

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and performance metrics of the primary target identification strategies used in NP research today.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Modern Target Identification Strategies for Natural Products

| Strategy | Key Principle | Typical Applications | Throughput | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Proteomics (e.g., ABPP) | Uses chemical probes to covalently label and isolate protein targets from complex biological mixtures [9]. | Direct target deconvolution; identification of covalent binders [9]. | Medium | Identifies targets in a native cellular environment; can profile entire proteomes [9]. | Requires synthetic modification of the NP to create a probe [9]. |

| Protein Microarray | Incubates the NP with thousands of immobilized proteins on a chip to detect binding events [9]. | High-throughput screening of binding interactions against a predefined protein set [9]. | High | Exceptionally high throughput for defined proteomes [9]. | Limited to pre-expressed proteins; may lack native cellular context [9]. |

| Affinity Purification | The NP is immobilized on a solid support to "fish out" binding proteins from cell or tissue lysates [4]. | Direct target "fishing"; one of the classic affinity-based strategies [4]. | Low to Medium | Conceptually straightforward; does not always require complex probe design [4]. | Can yield non-specific binders; requires a suitable functional group on the NP for immobilization [4]. |

| Network Pharmacology | Computational prediction of targets based on big data analysis of pharmacological networks and bioactivity spectra [9]. | Hypothesis generation; mapping polypharmacology of multi-target NPs [9]. | Very High | Holistically maps the polypharmacology of multi-target NPs; cost-effective [9]. | Predictions require experimental validation; indirect evidence of binding [9]. |

| Multi-omics Analysis | Integrates data from transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to infer targets and pathways [9]. | Systems-level understanding of NP mechanism of action and downstream effects [9]. | High | Provides a comprehensive, systems-level view of the NP's effect [9]. | Reveals downstream effects rather than direct protein targets [9]. |

| Similarity-Based Prediction (e.g., CTAPred) | Predicts targets for a query NP based on structural similarity to compounds with known target annotations [10]. | Rapid, cost-effective virtual screening for target hypothesis generation [10]. | Very High | Rapid and cost-effective; ideal for prioritizing NPs for further study [10]. | Accuracy depends on the quality and relevance of the reference database; predictive only [10]. |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

To illustrate the application of these technologies, below are detailed protocols for two widely adopted and powerful methods.

Protocol 1: Affinity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) for Target Identification

This chemical proteomics workflow is a powerful method for direct target deconvolution in live cells [9] [4].

- Probe Design and Synthesis: A functionalized derivative of the natural product (e.g., Celastrol) is synthesized. This derivative contains a reactive group (e.g., an alkyne) for "click chemistry" and a photoactivatable group (e.g., a diazirine) for covalent crosslinking upon UV irradiation.

- Cell Treatment and Photo-Crosslinking: Live cells or tissue samples are treated with the NP probe. After allowing for cellular uptake and binding, the samples are exposed to UV light, activating the diazirine and covalently "locking" the probe to its direct protein targets.

- Cell Lysis and "Click" Chemistry: The cells are lysed, and the alkyne-tagged protein-probe complexes are conjugated to an affinity tag (e.g., biotin) via a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition ("click" reaction).

- Affinity Purification: The biotin-tagged protein complexes are isolated from the lysate using streptavidin-coated beads.

- On-Bead Digestion and LC-MS/MS Analysis: The captured proteins are digested into peptides on the beads, and the resulting peptides are analyzed by Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for protein identification.

- Target Validation: Identified candidate targets must be validated using orthogonal methods such as:

Protocol 2: Similarity-Based Target Prediction with CTAPred

This computational protocol offers a rapid, in silico approach to generate testable hypotheses for a NP's protein targets [10].

- Dataset Curation: A high-quality reference dataset is compiled from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL, NPASS). This dataset contains compounds with standardized structures and reliably annotated protein target activities.

- Fingerprint Calculation: Molecular fingerprints (numerical representations of chemical structure) are computed for all compounds in the reference dataset and for the query NP.

- Similarity Search: The tool calculates the structural similarity (e.g., using Tanimoto coefficient) between the query NP and every compound in the reference dataset.

- Hit Ranking and Target Assignment: The reference compounds are ranked based on their similarity to the query NP. The protein targets associated with the top-N most similar reference compounds (e.g., top 5) are assigned as the predicted targets for the query NP.

- Experimental Prioritization and Validation: The resulting list of predicted targets provides a prioritized roadmap for subsequent experimental validation using the methods described in Protocol 1 or other biochemical/cellular assays.

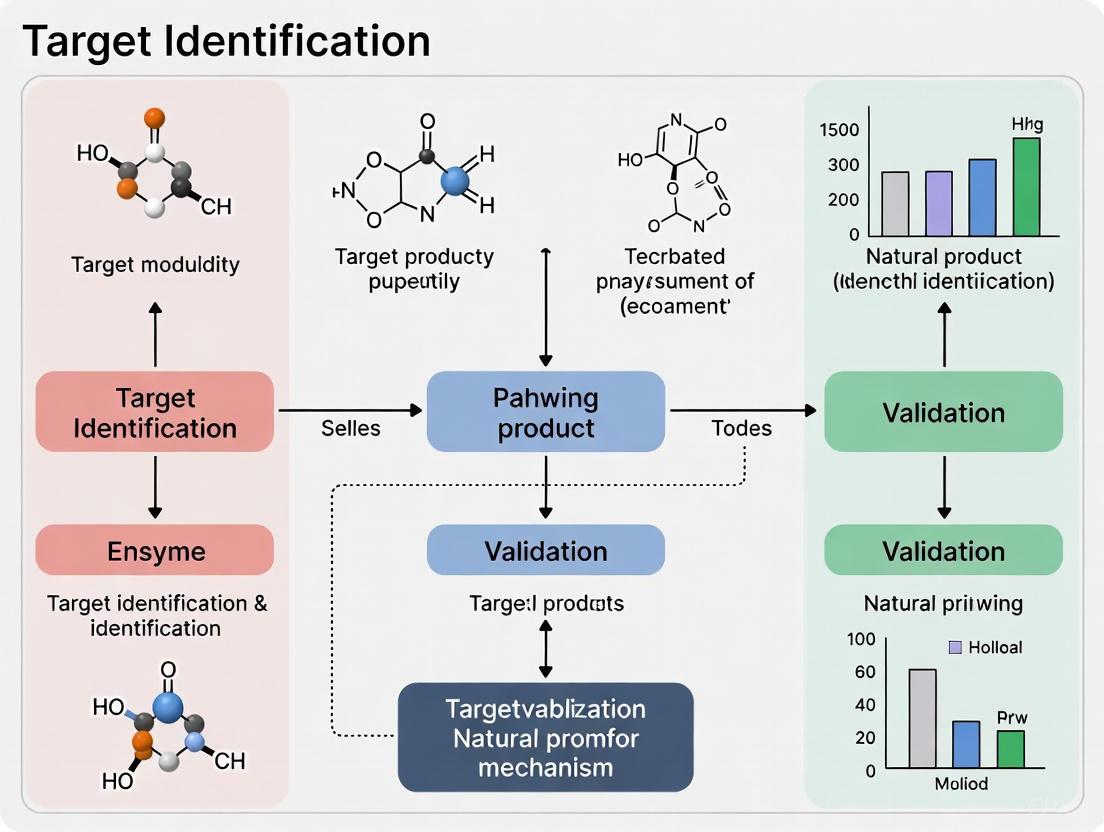

Visualizing the Systematic Discovery Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from hypothesis generation to experimental validation, showcasing how modern strategies overcome historical hurdles.

(Caption: Integrated workflow for systematic target discovery of natural products, combining computational and experimental strategies.)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful execution of these advanced protocols relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Target Identification Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized NP Probe | A chemically modified derivative of the natural product containing reactive groups (e.g., alkyne, diazirine) for labeling and purification. | Serves as the molecular bait in ABPP to covalently capture direct protein targets [9]. |

| Streptavidin-Coated Beads | Solid-phase support with high affinity for biotin, used for isolating biotin-tagged protein complexes. | Critical for affinity purification steps in ABPP to pull down probe-bound targets from a complex lysate [9] [4]. |

| "Click Chemistry" Reagents | A set of reagents (e.g., biotin-azide, CuSO₄, reducing agent) for the bioorthogonal conjugation of an alkyne group to an azide. | Links the alkyne-tagged NP probe to a biotin affinity tag for subsequent purification [4]. |

| Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) Buffers | Specialized cell lysis and protein stabilization buffers for thermal shift experiments. | Validates target engagement by measuring the ligand-induced change in the target protein's thermal stability [9]. |

| Curated Bioactivity Database | A compiled dataset of compounds with known protein target annotations (e.g., from ChEMBL, NPASS). | Serves as the reference library for similarity-based target prediction tools like CTAPred [10]. |

| LC-MS/MS Grade Solvents | Ultra-pure solvents and enzymes (e.g., trypsin) compatible with mass spectrometry. | Essential for digesting and analyzing purified protein samples to identify candidate targets [9]. |

The journey from serendipitous discovery to systematic decoding represents a paradigm shift in natural products research. While each technology platform profiled—from the direct capture of chemical proteomics to the predictive power of computational tools—carries its own strengths and limitations, their true power is realized through integration. The future of NP-based drug development lies in leveraging these tools in a complementary fashion, using computational insights to guide experimental design and employing high-precision experimental data to refine predictive models. This synergistic approach is finally dismantling the historical barriers that have long hindered the field, paving a rational and efficient path for transforming traditional remedies into the modern pharmaceuticals of tomorrow.

Defining 'Targets' and 'Validation' in a Natural Product Context

In the realm of natural product research, the terms 'targets' and 'validation' carry specific and critical meanings. A target is typically defined as a specific biological molecule, most often a protein (such as receptors, ion channels, kinases, or transporters), with which a bioactive natural product directly interacts to produce its therapeutic effect [4]. Target validation is the comprehensive process of experimentally confirming that this identified molecule is not only bound by the compound but is also functionally responsible for the observed pharmacological outcome [7]. For natural products with complex mechanisms, moving from a simple observation of bioactivity to a clear understanding of the molecular target is a fundamental challenge. Mastering this process is crucial for elucidating the biological pathways involved, optimizing drug efficacy, minimizing side effects, and guiding the development of novel, safer therapeutics [4]. This guide objectively compares the performance of key technologies used for this purpose, providing a framework for researchers in drug development.

Core Methodologies for Target Identification and Validation

Several established and emerging technologies enable researchers to "fish" for and confirm the cellular targets of natural products. The following section compares these core methodologies, highlighting their principles, applications, and performance data.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Target Identification & Validation Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Typical Throughput | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Direct Measure of Engagement in Live Cells? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Purification [4] | Uses an immobilized compound as "bait" to pull down binding proteins from a complex biological lysate. | Medium | Direct physical isolation of target proteins for identification. | Requires chemical modification of the compound; may not work for weak/transient interactions. | No (uses cell lysates) |

| Photoaffinity Labeling [4] | Incorporates a photoactivatable moiety into a probe; upon UV irradiation, it forms a covalent bond with the target protein. | Low | "Traps" transient interactions, enabling harsh purification steps. | Complex probe synthesis; potential for non-specific labeling. | Yes |

| Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) [7] | Measures the thermal stabilization of a target protein upon ligand binding in an intact cellular environment. | Medium to High | Confirms target engagement in physiologically relevant conditions (live cells/tissues). | Does not directly identify novel/unknown targets. | Yes |

| Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS) [4] | Exploits the increased proteolytic resistance of a protein when bound to a small molecule. | Medium | Does not require chemical modification of the compound. | Can be prone to false positives from protease substrate preferences. | No (uses cell lysates) |

| In Silico Target Prediction [11] | Uses AI/machine learning models to predict ligand-target interactions based on chemical structure similarity and known data. | Very High | Rapid, low-cost prioritization of potential targets for experimental validation. | Predictive only; requires empirical confirmation. | N/A |

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

To ensure reproducibility and facilitate comparison, this section provides detailed methodologies for two pivotal and complementary experimental approaches: one for initial target identification and another for functional validation in a live-cell context.

Protocol 1: Affinity Purification (Target Fishing)

This classic, yet continuously refined, strategy is used for the direct isolation of protein targets [4].

Step 1: Probe Synthesis

- Procedure: Chemically modify the natural product of interest to introduce a functional group (e.g., an amino or carboxyl group) without altering its core bioactive structure. This handle is then used to covalently link the compound to solid support beads (e.g., Sepharose or magnetic beads) via a spacer arm [4].

- Critical Controls: Simultaneously prepare control beads using a structurally similar but inactive compound or beads with the spacer arm alone.

Step 2: Affinity Purification

- Procedure: Incubate the compound-conjugated beads with a prepared protein lysate from relevant cells or tissues. After incubation, wash the beads extensively with buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the specifically bound proteins using a competitive agent (e.g., a high concentration of the free natural product) or by denaturing conditions (e.g., SDS buffer) [4] [11].

- Key Parameter: Use the control beads in a parallel experiment to identify and subtract proteins that bind non-specifically to the matrix or spacer.

Step 3: Target Identification

- Procedure: Analyze the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE followed by in-gel digestion, or directly by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Identify the proteins by searching the resulting mass spectra against protein databases [4].

Protocol 2: Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)

This method quantitatively validates target engagement by measuring ligand-induced thermal stabilization of the putative target protein in its native cellular environment [7].

Step 1: Compound Treatment and Heat Denaturation

- Procedure: Treat intact cells with the natural product or a vehicle control (DMSO) for a predetermined time. After treatment, divide the cell suspension into aliquots and heat each to a different temperature (e.g., a gradient from 37°C to 65°C) for a fixed time (e.g., 3 minutes) [7].

Step 2: Protein Solubility Analysis

- Procedure: Lyse the heat-exposed cells and separate the soluble protein (heat-stable) from the aggregated protein (heat-denatured) by high-speed centrifugation. The target protein, if stabilized by the compound, will remain soluble at higher temperatures compared to the control sample [7].

Step 3: Quantification

- Procedure: Quantify the amount of soluble target protein remaining in each sample by immunoblotting (Western blot) for the known putative target or, for an unbiased approach, using high-resolution mass spectrometry [7].

- Data Analysis: Plot the fraction of soluble protein remaining against the temperature. A rightward shift in the melting curve (increased melting temperature, Tm) for the compound-treated sample confirms direct target engagement [7].

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical workflows of the core methodologies and a generalized signaling pathway impacted by a natural product, helping to clarify the complex relationships involved.

Target Identification and Validation Workflow

Example Natural Product Signaling Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful target identification and validation relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below details essential items for constructing a robust research pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Target ID & Validation

| Research Reagent / Solution | Critical Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Natural Product Probe | Serves as molecular "bait" for affinity purification; contains a chemical handle (e.g., alkyne, biotin) for conjugation [4]. | Modification must not impair bioactivity. Control probes are essential. |

| Solid Support Matrix (e.g., Sepharose 4B, Magnetic Beads) | The solid-phase platform for immobilizing the probe to isolate binding proteins from a complex mixture [4] [11]. | Choice depends on lysate type and required binding capacity. Low non-specific binding is critical. |

| Photoactivatable Moieties (e.g., Diazirine, Benzophenone) | Incorporated into probes for photoaffinity labeling; forms covalent cross-links with proximal proteins upon UV light exposure [4]. | Diazirines are smaller and can generate more highly reactive carbenes. |

| Click Chemistry Reagents (e.g., Azide-Biotin, Cu(I) Catalyst) | Enables bioorthogonal conjugation, such as labeling an alkyne-tagged probe or protein with a detectable tag (biotin, fluorophore) after cellular uptake [4]. | Allows for minimal functionalization of the native compound. |

| CETSA / MS-Compatible Lysis Buffer | Maintains protein stability and solubility during the thermal shift protocol, enabling accurate quantification of soluble protein [7]. | Must be compatible with downstream mass spectrometry analysis. |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry System | The core analytical tool for unbiased identification of pulled-down proteins or thermally stabilized proteins in CETSA workflows [4] [7]. | High sensitivity and accuracy are required to detect low-abundance targets. |

In the competitive landscape of modern drug discovery, natural products (NPs) continue to provide an unparalleled foundation for identifying novel therapeutic targets and lead compounds. Their enduring value stems from two fundamental advantages: immense structural diversity honed through evolutionary processes and inherent biological pre-optimization for interacting with biological systems. While synthetic approaches often pursue single-target specificity, natural products operate through sophisticated polypharmacological mechanisms, simultaneously modulating multiple biological pathways—a characteristic particularly advantageous for treating complex diseases like cancer, chronic inflammation, and neurodegenerative disorders [4] [12]. This review objectively compares the performance of natural product-based approaches against synthetic alternatives within target identification and validation workflows, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to inform their mechanistic studies.

The evolutionary refinement of natural products confers distinct advantages in drug discovery. Over millennia, organisms have optimized these compounds for specific biological functions, including defense, signaling, and communication, resulting in molecules with superior biological relevance compared to purely synthetic libraries [13]. These compounds typically exhibit favorable molecular properties—including appropriate molecular weight, rigidity, and stereochemical complexity—that enable effective interaction with biomacromolecules [13]. Furthermore, their inherent structural diversity provides access to chemical space largely unexplored by synthetic compounds, making them invaluable for identifying novel druggable targets [4] [14].

Structural Diversity of Natural Products: A Quantitative Comparison

The structural complexity of natural products represents their most significant advantage over synthetic compound libraries. This diversity manifests in several key metrics that directly impact target identification and drug discovery outcomes.

Chemical Space Coverage and Scaffold Diversity

Natural products access regions of chemical space typically unavailable to synthetic compounds due to their complex ring systems, diverse stereochemistry, and unique functional group arrangements. The following table quantifies this structural diversity across major natural product classes:

Table 1: Structural Diversity Metrics Across Natural Product Classes

| Natural Product Class | Representative Examples | Number of Documented Structures | Unique Ring Systems | Stereogenic Centers (Avg.) | Target Classes Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sesterterpenoids | Various fungal metabolites | >1,600 [14] | 45+ core scaffolds | 5-12 | Antimicrobial, Anticancer [14] |

| Alkaloids | Berberine, Morphine | >12,000 | 20+ backbone structures | 3-8 | CNS, Cardiovascular [13] |

| Flavonoids | Quercetin, Paeoniflorin | >6,000 | 3 major scaffolds with high decoration | 2-5 | Kinases, Inflammatory targets [12] |

| Polyketides | Artemisinin | >10,000 | Highly variable | 4-15 | Antimalarial, Antimicrobial [4] |

| Glycosides | Ginsenosides, Digoxin | >5,000 | Variable aglycone + sugar motifs | 5-10 | Ion channels, Receptors [4] [13] |

This structural complexity directly translates to enhanced target engagement capabilities. Comparative studies indicate that natural products and their derivatives show a 2.3-fold higher hit rate in phenotypic screenings compared to purely synthetic compounds [13]. Furthermore, their inherent molecular rigidity facilitates more specific binding interactions, with natural product-derived leads demonstrating approximately 40% lower entropic penalties upon target binding compared to synthetic compounds [13].

Performance Comparison: Natural Product-Derived vs. Synthetic Compounds

The biological pre-optimization of natural products provides tangible advantages in key drug discovery metrics, as evidenced by comparative analyses of approved therapeutics:

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Natural Product-Derived vs. Synthetic Drugs (2000-2025)

| Parameter | Natural Product-Derived Drugs | Synthetic Drugs | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Success Rate | ~15% | ~7% | [12] |

| Average Number of Target Proteins | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | [4] [11] |

| Molecular Complexity (Fsp3) | 0.47 ± 0.15 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | [15] |

| Structural Novelty (vs. Known Compounds) | 78% novel scaffolds | 42% novel scaffolds | [4] |

| Therapeutic Areas of Dominance | Anti-infectives, Oncology, Immunology | CNS, Cardiovascular | [12] [13] |

The data demonstrates that natural product-derived compounds achieve significantly higher clinical success rates, largely attributable to their evolutionary optimization for biological systems. Their structural complexity, quantified by the fraction of sp3 hybridized carbon atoms (Fsp3), correlates with improved physicochemical properties and enhanced clinical outcomes [15]. Furthermore, natural products consistently provide access to novel molecular scaffolds, with approximately 78% of recently discovered natural products representing previously uncharacterized chemical architectures [4].

Experimental Approaches for Target Identification of Natural Products

Identifying molecular targets for natural products presents unique challenges due to their complex structures, low abundance, and multi-target nature. Modern approaches have evolved from single-method strategies to integrated workflows that combine multiple complementary techniques:

Diagram 1: Integrated target identification workflow for natural products showing the multi-technique approach required for comprehensive target deconvolution.

Key Technologies: Principles and Experimental Protocols

Affinity Purification and Chemical Probe Design

The affinity purification strategy represents a cornerstone approach for direct target identification. This method involves modifying natural products with linker molecules while preserving their biological activity, followed by immobilization onto solid supports for target "fishing" from complex biological samples [4].

Protocol: Affinity Matrix Preparation and Target Fishing

- Chemical Probe Design: Introduce functional groups (amino, carboxyl, hydroxyl) to the natural product structure at positions not critical for bioactivity [4].

- Immobilization: Couple the modified natural product to NHS-activated Sepharose 4B beads or magnetic microspheres via amine coupling chemistry [4] [11].

- Control Matrix: Prepare parallel control matrix with identical chemistry but lacking the natural product.

- Incubation: Expose the affinity matrix to cell or tissue lysates (typically 1-5 mg protein/mL) for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Washing: Remove non-specifically bound proteins through sequential washing with lysis buffer containing increasing salt concentrations (0.15-1 M NaCl).

- Elution: Recover specifically bound targets using competitive elution (excess free natural product) or denaturing conditions (SDS buffer).

- Identification: Analyze eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [4].

Performance Data: This approach successfully identified CDK2 as a direct target of curcumin, with binding affinity (Kd) of 0.35 μM confirmed by surface plasmon resonance [11]. In another study, affinity purification revealed 138 target proteins for Shouhui Tongbian Capsule, enabling mapping to eight signaling pathways [11].

Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)

CETSA has emerged as a powerful label-free method for detecting target engagement in intact cells and native tissues, providing functional validation of direct target interactions [12] [7].

Protocol: CETSA for Natural Product Target Validation

- Compound Treatment: Expose cells (typically 1-2×10^6 cells/mL) to the natural product at relevant concentrations (typically IC50 values) for 2-4 hours.

- Heat Denaturation: Aliquot cell suspensions, subject to a temperature gradient (37-65°C) for 3 minutes in a thermal cycler.

- Cell Lysis: Freeze-thaw cycles or mechanical disruption to liberate soluble proteins.

- Soluble Protein Isolation: Centrifuge at 20,000×g for 20 minutes at 4°C to separate soluble proteins from aggregates.

- Protein Quantification: Analyze soluble fractions by Western blot or quantitative mass spectrometry.

- Data Analysis: Calculate melting temperature (Tm) shifts between treated and untreated samples. Significant rightward shifts (≥2°C) indicate stabilization due to compound binding [7].

Performance Data: CETSA applications have confirmed direct binding between quercetin and 17 cellular targets in anti-aging studies, with thermal shifts ranging from 2.1-6.8°C [12]. In rat tissue studies, CETSA validated DPP9 engagement by experimental compounds with clear dose-dependent and temperature-dependent stabilization [7].

Computational Target Fishing and AI Integration

Computational approaches have dramatically accelerated natural product target identification by prioritizing candidates for experimental validation [11].

Protocol: Computational Target Prediction Pipeline

- Structure Preparation: Obtain 2D/3D molecular structures of natural products from databases (e.g., NPASS, SuperNatural II).

- Descriptor Calculation: Generate molecular descriptors (topological, electronic, geometrical) and molecular fingerprints.

- Similarity Searching: Compare against curated databases of known ligand-target interactions (ChEMBL, BindingDB) using similarity algorithms (Tanimoto coefficient ≥0.85).

- Molecular Docking: Perform flexible docking against potential targets using AutoDock Vina or Glide.

- Machine Learning: Apply trained models (Random Forest, Deep Neural Networks) to predict binding probabilities.

- Network Analysis: Construct compound-target-disease networks to identify biologically relevant targets [11].

Performance Data: Recent implementations integrating deep learning with knowledge graphs have improved target prediction accuracy by 40-60% compared to traditional similarity-based methods [11]. For Beimu compounds used in cough treatment, computational target fishing identified 23 potential target proteins, subsequently validated for 18 targets (78% validation rate) [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful target identification for natural products requires specialized reagents and methodologies optimized for their structural complexity:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Natural Product Target Identification

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immobilization Matrices | NHS-activated Sepharose 4B, Epoxy-activated magnetic microspheres | Covalent immobilization of natural product probes for affinity purification | Control for non-specific binding; maintain bioactivity post-immobilization [4] |

| Photoactivatable Groups | Diazirine, Benzophenone | Incorporate into natural products for photoaffinity labeling; enable UV-induced crosslinking with targets | Minimal structural perturbation; efficient crosslinking yield [4] |

| Bioorthogonal Handles | Azide, Alkyne, Tetrazine | Enable click chemistry conjugation for visualization and pull-down experiments | Metabolic stability; minimal impact on natural product bioactivity [4] |

| Thermal Shift Assay Kits | CETSA-compatible cell lysis buffers, Proteostasis indicators | Measure target engagement and stabilization in intact cellular environments | Compatibility with mass spectrometry; cell permeability of natural products [7] |

| Computational Platforms | PharmMapper, SEA, SwissTargetPrediction | In silico target prediction based on structural similarity and pharmacophore mapping | Curated natural product databases; appropriate similarity thresholds [11] |

| Validation Assays | SPR chips, DARTS reagents, Cellular functional assay kits | Confirm direct binding and functional consequences of target engagement | Physiological relevance; appropriate controls for polypharmacology [12] |

Case Studies: Successful Target Identification of Bioactive Natural Products

Artemisinin and Derivatives: Multi-Target Antimalarial Action

The antimalarial natural product artemisinin exemplifies the advantage of natural product complexity in target identification. Recent chemical proteomics approaches revealed an unanticipated human target of artesunate, demonstrating that its therapeutic effects extend beyond malaria parasites to human host targets [4]. Through photoaffinity labeling and clickable probes, researchers identified multiple protein targets involved in heme detoxification, protein degradation, and oxidative stress response, explaining its potent and rapid antimalarial action [4].

Experimental Data: Proteomic profiling identified 124 artemisinin-binding proteins in Plasmodium falciparum, with enrichment in processes including translation, proteolysis, and antioxidant defense. Direct binding to PfATP6 was confirmed with Kd of 2.3 μM, while engagement with human porphobilinogen deaminase suggested additional mechanisms contributing to the drug's efficacy [4].

Berberine: Systems-Level Mechanisms for Metabolic Disease

Berberine provides a compelling case study of how natural products achieve therapeutic effects through multi-target mechanisms. Initially known for antimicrobial properties, target identification efforts revealed its ability to interact with multiple metabolic regulators.

Experimental Approach: Reverse docking predicted 32 potential targets for berberine, while affinity purification using berberine-functionalized matrices captured 15 specific binding proteins from hepatic tissues [11]. Functional validation confirmed direct binding to aldose reductase (Kd = 0.84 μM) and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (Kd = 1.2 μM), explaining its insulin-sensitizing effects [11].

Performance Metrics: The multi-target profile of berberine results in a 3.5-fold higher therapeutic index for metabolic syndrome compared to single-target synthetic agents, demonstrating the clinical advantage of natural product polypharmacology [11].

Celastrol: Complex Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms

The anti-inflammatory natural product celastrol exemplifies the need for integrated approaches to fully characterize natural product mechanisms.

Experimental Approach: Combined affinity purification and thermal proteome profiling identified peroxiredoxins and heat shock proteins as direct targets of celastrol [4]. Subsequent functional assays demonstrated that celastrol induces ferroptosis in activated hepatic stellate cells by targeting peroxiredoxins and HO-1, providing a mechanistic basis for its anti-fibrotic effects [4].

Pathway Analysis: The target identification data revealed that celastrol simultaneously modulates Nrf2 antioxidant response, NF-κB inflammatory signaling, and ferroptotic cell death pathways, creating a synergistic anti-inflammatory effect unattainable by single-target synthetic inhibitors [4].

Natural products provide unique advantages in target identification and validation that complement synthetic approaches. Their structural diversity and evolutionary optimization enable access to novel biological targets and pathways, particularly for complex diseases requiring multi-target modulation. The experimental data presented demonstrates that natural product-derived compounds consistently outperform purely synthetic molecules in hit rates, clinical success rates, and polypharmacological potential.

Future advancements in natural product research will increasingly rely on integrated workflows that combine chemical biology, proteomics, and artificial intelligence. As target identification technologies continue to evolve, particularly in areas of chemical proteomics, cellular thermal shift assays, and computational prediction, the unique value proposition of natural products will become increasingly accessible to drug discovery pipelines. For researchers pursuing challenging therapeutic targets, natural products remain an essential component of a comprehensive drug discovery strategy, offering chemical and biological starting points that cannot be replicated by purely synthetic approaches.

For centuries, traditional medicine systems across cultures have relied on botanical remedies to treat myriad health conditions. This accumulated ethnobotanical knowledge represents an invaluable resource for modern drug discovery, providing pre-filtered, bioactivity-enriched starting points that significantly increase the efficiency of identifying therapeutic compounds. The World Health Organization reports that over 80% of people worldwide rely on traditional medicine for primary healthcare, with plant-based treatments forming the cornerstone of these practices [16]. This extensive real-world testing over generations provides a powerful validation filter that modern science can leverage through rigorous target identification and validation approaches.

The historical success of this approach is undeniable, with numerous blockbuster pharmaceuticals tracing their origins to traditional plant medicines. Artemisinin for malaria was discovered through the systematic investigation of Artemisia annua, long used in Chinese traditional medicine [17]. Similarly, the analgesic morphine was isolated from the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), a plant with centuries of traditional use for pain relief [17]. These successes demonstrate that traditional knowledge can dramatically accelerate modern drug discovery by providing high-confidence hypotheses for pharmacological investigation.

Contemporary research continues to validate this approach. A 2023 large-scale analysis of ethnobotanical patterns demonstrated that congeneric medicinal plants (plants belonging to the same genus) are statistically more likely to be used for similar therapeutic indications across different cultures and geographical regions [18]. This non-random distribution strongly suggests conserved bioactivity driven by shared phytochemistry, providing a systematic framework for prioritizing plants for pharmacological investigation.

Quantitative Evidence: Systematic Analysis of Ethnobotanical Patterns

Recent research provides compelling quantitative evidence supporting the predictive value of traditional plant knowledge. A 2023 large-scale cross-cultural analysis investigated the relationship between taxonomic classification and therapeutic usage patterns across thousands of medicinal plants [18].

Table 1: Correlation Between Taxonomic Relationship and Medicinal Usage Similarity

| Taxonomic Relationship | Medicinal Usage Correlation | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Congeneric plants (same genus) | High correlation for treating similar indications | Strong (p < 0.001) |

| Confamilial plants (same family) | Moderate correlation | Variable significance |

| Random plant pairs | No significant correlation | Not significant |

This systematic analysis demonstrated that congeneric medicinal plants are significantly more likely to be used for similar therapeutic purposes across disparate cultures and geographical regions [18]. For example, different species of Tinospora growing in India (T. cordifolia) and Nigeria (T. bakis) are both traditionally used to treat liver diseases and jaundice, despite their geographical separation [18]. Similarly, Glycyrrhiza uralensis (Asia) and Glycyrrhiza lepidota (North America) are both used for cough and sore throat [18]. This conserved usage pattern suggests non-random bioactivity resulting from shared phytochemistry due to evolutionary relationships.

The underlying mechanism for these conserved therapeutic properties appears to be phytochemical similarity among related plants. The same study found that taxonomically related medicinal plants not only treat similar diseases but also occupy similar phytochemical space, with chemical similarity correlating significantly with similar therapeutic usage [18]. This provides a scientific foundation for using ethnobotanical knowledge as a prioritization filter in natural product discovery.

Modern Target Identification Technologies: From Traditional Remedies to Validated Mechanisms

Once promising botanical leads are identified through ethnobotanical investigation, modern technologies are essential for identifying their molecular targets and mechanisms of action—a critical step in developing standardized therapeutics.

Proteomics-Driven Target Identification

Affinity-based proteomics approaches enable systematic identification of protein targets that directly interact with bioactive natural compounds:

Affinity Purification (Target Fishing): This classical approach immobilizes natural compounds or their derivatives on solid supports to "fish" binding proteins from complex biological samples like cell lysates. Specific interactions are identified through mass spectrometry analysis [4].

Click Chemistry and Photoaffinity Labeling: These techniques incorporate bioorthogonal functional groups or photoreactive moieties into natural product probes, enabling covalent cross-linking with target proteins under physiological conditions for subsequent identification [4].

Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA): This method detects drug-target engagement by measuring the thermal stabilization of proteins upon ligand binding in intact cellular environments. When coupled with mass spectrometry (CETSA-MS), it enables proteome-wide mapping of target interactions [12] [7].

Computational and Multi-Omics Integration

Modern target identification increasingly combines experimental approaches with computational methods:

Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulations: These in silico approaches predict how natural compounds interact with potential protein targets at atomic resolution, providing mechanistic insights and prioritizing experimental validation [19].

Multi-Omics Platforms: Integrated genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics provide comprehensive views of natural product effects on biological systems, revealing complex mechanisms and polypharmacology [17].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Target Identification Technologies for Natural Products

| Technology | Key Principle | Throughput | Physiological Relevance | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Purification | Physical capture of binding partners using immobilized compound | Medium | Low (cell lysates) | Initial target discovery, identifying direct interactors |

| CETSA/CETSA-MS | Thermal stabilization of target proteins upon binding | Medium to High | High (intact cells/tissues) | Target engagement confirmation, proteome-wide screening |

| Click Chemistry/Photoaffinity Labeling | Covalent cross-linking with bioorthogonal handles | Medium | Medium to High | Identifying transient interactions, subcellular localization |

| Molecular Docking/Dynamics | Computational prediction of binding poses and stability | High | Variable (structure-dependent) | Hypothesis generation, binding site prediction, mechanism |

| Multi-Omics Integration | Systems-level analysis of molecular responses | High | High | Comprehensive mechanism elucidation, polypharmacology |

Diagram 1: The integrated ethnobotany to therapeutics pipeline shows how traditional knowledge guides modern drug discovery.

Case Study: Integrated Ethnobotanical and Computational Validation of Anti-Influenza Botanicals

A 2024 study on medicinal plants traditionally used for influenza treatment in the Democratic Republic of the Congo exemplifies the integrated approach to validating traditional knowledge [19]. Researchers combined ethnobotanical surveys with computational validation to identify and mechanistically characterize promising botanical therapeutics.

Experimental Protocol

Ethnobotanical Data Collection: Researchers employed snowball sampling to identify knowledgeable informants, using semi-structured questionnaires to document plants used for influenza-like symptoms. Cultural significance was quantified through informant consensus factor and use agreement value calculations [19].

Molecular Docking and Dynamics: Bioactive compounds from prioritized plants were computationally screened against influenza virus neuraminidase protein. Molecular dynamics simulations assessed complex stability over time, with specific analysis of hydrogen bonding patterns and binding free energies [19].

Key Findings

The integrated approach identified several plants with strong potential, with two particularly promising species:

Cymbopogon citratus (Lemongrass): Contains neral, which formed two hydrogen bonds with the neuraminidase active site [19].

Ocimum gratissimum: Contains eugenol, which formed four hydrogen bonds with key residues (Arg706, Val709, Ser712, Arg721) [19].

Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed stable binding, with approximately 300 amino acid residues participating in ligand interactions, suggesting strong binding affinity and specificity [19]. This mechanistic validation at the molecular level provides scientific support for traditional use while identifying specific compounds for further development.

Diagram 2: Combined workflow shows integration of traditional knowledge with computational validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Target Identification

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Natural Product Target Identification

| Research Reagent/Platform | Function in Target Identification | Key Applications in Natural Products Research |

|---|---|---|

| CETSA Reagents & Kits | Detect target engagement by measuring thermal stability shifts in cellular systems | Validation of direct target binding in physiologically relevant environments [7] |

| Photoaffinity Probes | Covalently crosslink natural products to their protein targets for subsequent isolation | Identification of direct molecular targets, especially for weak or transient interactions [4] |

| Click Chemistry Toolkits | Incorporate bioorthogonal handles into natural products for visualization and pulldown | Target identification in live cells, subcellular localization studies [4] |

| Affinity Resins | Immobilize natural compounds for fishing experiments | Pull-down of direct binding partners from complex protein mixtures [4] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Predict binding modes and affinities of natural compounds to potential targets | Virtual screening of natural product libraries, binding hypothesis generation [19] |

| Multi-Omics Databases | Integrate genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data for systems biology analysis | Uncovering polypharmacology and complex mechanisms of action [17] |

The integration of traditional ethnobotanical knowledge with modern target identification technologies represents a powerful paradigm for natural product-based drug discovery. This approach leverages the best of both worlds: the real-world validation of traditional medicines and the mechanistic precision of modern molecular technologies. As target identification methods continue to advance—particularly through artificial intelligence and multi-omics integration—the path from ethnobotanical leads to validated therapeutics will become increasingly efficient and productive [17] [7]. This synergy promises to accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic agents while preserving and validating invaluable traditional knowledge systems.

A Practical Guide to Modern Target Identification Techniques: From Chemical Proteomics to AI

In the progression of human disease treatment, a central challenge in drug discovery lies in the precise identification and validation of molecular targets that can modulate disease pathways [11]. This challenge is particularly acute for natural products (NPs), which are pivotal in traditional medicine and modern pharmacology, serving as valuable sources of drugs and drug leads [10]. Historically, the field has relied on conventional strategies such as phenotypic screening, genomics analysis, and chemical genetics approaches [11]. However, these methods often suffer from inherent limitations, including low screening throughput and protracted timelines for target validation, frequently leaving potential targets obscured within biological systems' complexity [11].

To address these limitations, innovative research strategies represented by "target fishing" have emerged, integrating chemical biology, high-resolution proteomics, and artificial intelligence technologies [11]. This approach drives drug discovery from an experience-oriented paradigm toward a data-driven one, using active small molecules as probes to directly "fish" for binding proteins from complex biological samples [11]. Among the various techniques available, chemical proteomics has established itself as the gold standard for direct target identification, enabling researchers to comprehensively identify protein targets of active small molecules at the proteome level in an unbiased manner [20] [21].

Table: Comparison of Target Identification Approaches

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Proteomics | Uses chemical probes to enrich molecular targets from biological samples [20] | Unbiased, proteome-wide, works in native biological context [21] | Requires probe synthesis, potential for false positives [20] |

| Computational Prediction | Predicts targets based on chemical similarity to compounds with known targets [10] | Rapid, cost-effective, no synthesis required [10] | Limited by database coverage, may miss novel targets [10] |

| Transcriptome Profiling | Analyzes gene expression changes after compound treatment [20] | Provides functional context, measures downstream effects [20] | Indirect identification, complex data interpretation [20] |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid | Detects protein-protein interactions in yeast system [21] | Genetic readout, functional context [21] | Limited applicability, multiple interference [20] |

Chemical Proteomics: Principles and Workflows

Chemical proteomics represents a postgenomic version of classical drug affinity chromatography that is coupled to subsequent high-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) and bioinformatic analyses [20]. As an important branch of proteomics, it integrates diverse approaches in synthetic chemistry, cellular biology, and mass spectrometry to comprehensively fish and identify multiple protein targets of active small molecules [20]. The approach consists of two key steps: (1) probe design and synthesis and (2) target fishing and protein identification [20].

Chemical proteomics methodologies can be divided into two principal categories based on their operational workflows: activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) and compound-centric chemical proteomics (CCCP) [20]. ABPP combines activity-based probes and proteomics technologies to identify protein targets, typically employing probes that retain the pharmacological activity of their parent molecules [20]. In contrast, CCCP originates from classic drug affinity chromatography and merges this classical method with modern proteomics by immobilizing drug molecules on a matrix such as magnetic or agarose beads [20].

Figure 1: Core Workflow of Chemical Proteomics Approaches for Target Identification

Probe Design: The Critical First Step

Designing and synthesizing the probe is the initial and pivotal step for target identification in chemical proteomics approaches [20]. Generally, a probe consists of three essential components [20]:

- Reactive group: Derived from the parent drug molecule, ensuring retention of pharmacological activity and ability to bind protein targets

- Reporter tag: Such as biotin, an alkyne, or fluorescence group for target enrichment or detection

- Linker: Sometimes cleavable, connects the reactive group and reporter tag, designed to be long enough to avoid steric hindrance

The structure of the probe varies significantly across different chemical proteomics strategies, with some approaches omitting one or even two of these components depending on the specific application requirements [20].

Comparative Analysis of Chemical Proteomics Strategies

Major Probe Modalities in Chemical Proteomics

Chemical proteomics employs several distinct probe strategies, each with specific characteristics, advantages, and limitations suited to different experimental scenarios.

Immobilized Probes represent one of the earlier approaches, where bioactive natural products are covalently immobilized on biocompatible inert resins such as agarose and magnetic beads to serve as bait for target proteins [20]. This method benefits from the intrinsic properties of the beads, such as their macroscopic size and magnetism, which facilitate easy enrichment of probe-fished proteins for subsequent identification [20]. However, this convenience is counterbalanced by the challenge of high spatial resistance, which can lead to the loss of targets with weak binding affinity [21].

Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) were developed to overcome limitations of immobilized probes [21]. These probes incorporate reporter groups such as biotin for enrichment and fluorescent groups for detection [21]. A significant advancement in this category is the use of click chemistry reactions, particularly the azide-alkyne cycloaddition (AAC), which enables direct binding of the compound to the target in situ within living cells, thereby providing a more accurate depiction of small molecule-protein interactions [21].

Photoaffinity Probes represent an advanced iteration of ABPs based on the concept of photoaffinity labeling (PAL) [21]. These probes integrate photoreactive groups such as benzophenone, aryl azides, and diazirines [21]. Upon binding to the target protein and activation with wavelength-specific light (typically ultraviolet light at 365 nm), these probes release highly reactive chemicals that covalently cross-link proximal amino acid residues, effectively converting non-covalent interactions into covalent ones [21]. This approach is particularly useful for studying integral membrane proteins and identifying compound-protein interactions that may be too transient to detect by other methods [22].

Table: Comparison of Chemical Proteomics Probe Types

| Probe Type | Key Components | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immobilized Probes | Natural product covalently linked to solid support (e.g., agarose beads) [20] | High-affinity targets, straightforward enrichment [20] | High spatial resistance, may miss weak binders [21] |

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) | Reactive group + linker + reporter tag (biotin/fluorophore) [21] | Enzymatic targets, activity-based profiling [21] | Large reporter groups may alter compound activity [21] |

| Photoaffinity Probes | Reactive group + photoreactive moiety + enrichment handle [21] | Membrane proteins, transient interactions [22] | Requires UV activation, potential non-specific crosslinking [21] |

| Label-Free Approaches | No modification of native compound [22] | Native conditions, avoiding modification artifacts [22] | Challenging for low-abundance proteins [22] |

Experimental Performance and Applications

The true value of chemical proteomics is demonstrated through its application in identifying targets for natural products with complex mechanisms of action. For example, Schreiber et al. immobilized FK506 (tacrolimus), a natural immunosuppressant, to identify its protein targets [20]. After complete incubation with cytosolic extracts of bovine thymus and human spleen, followed by competitive elution with FK506, a 14 K protein was enriched and identified, leading to the discovery of FKBP12, which functions as a protein folding chaperone for proteins containing proline residues [20].

In another exemplary application, the structural optimization of berberine, the discovery of a PD-L1 inhibitor, and the elucidation of the mechanism of action of celastrol all validate the distinct advantages of "target fishing" using chemical proteomics in target identification and mechanistic exploration [11]. These successes highlight how chemical proteomics enables the direct identification of molecular targets within biologically relevant contexts, providing a more accurate representation of compound-protein interactions compared to computational predictions alone.

Figure 2: Step-by-Step Experimental Process for Chemical Proteomics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of chemical proteomics requires specialized reagents and materials designed to facilitate probe synthesis, target enrichment, and protein identification.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical Proteomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Supports | Agarose beads, magnetic beads [20] | Provide matrix for compound immobilization and target enrichment |

| Chemical Linkers | PEG linkers, cleavable linkers [20] | Connect reactive groups to reporter tags, minimize steric hindrance |

| Reporter Tags | Biotin, fluorescent tags (e.g., TAMRA, BODIPY) [21] | Enable detection and enrichment of target proteins |

| Click Chemistry Reagents | Azide-alkyne pairs, Cu(I) catalysts, cyclooctynes [21] | Facilitate bioorthogonal conjugation in living systems |

| Photoaffinity Groups | Benzophenone, aryl azides, diazirines [21] | Enable UV-induced covalent crosslinking with target proteins |

| Enrichment Matrices | Streptavidin beads, antibody resins [21] | Capture and purify probe-bound protein targets |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS systems, DIA/DDA capabilities [23] | Identify and quantify enriched proteins with high sensitivity |

Complementary and Emerging Technologies

While chemical proteomics represents the gold standard for direct target identification, several complementary technologies enhance its utility or offer alternative approaches for specific applications.

Label-Free Target Deconvolution strategies have been developed for cases where compound labeling is disruptive, technically challenging, or otherwise infeasible [22]. One prominent approach—solvent-induced denaturation shift assays—leverages the changes in protein stability that often occur with ligand binding [22]. By comparing the kinetics of physical or chemical denaturation before and after compound treatment, researchers can identify compound targets on a proteome-wide scale without requiring chemical modification of the native compound [22].

Computational Prediction Tools like CTAPred offer a complementary approach that uses similarity-based searches to predict protein targets for natural products [10]. These tools apply fingerprinting and similarity-based search techniques to identify potential protein targets for NP query compounds based on their similarity to reference compounds with known bioactivities [10]. While these computational methods cannot replace experimental validation, they provide valuable preliminary data to guide targeted chemical proteomics experiments.

Automated Proteomics Platforms such as the π-Station represent cutting-edge advancements that enable fully automated sample-to-data systems for proteomic experiments [23]. This platform seamlessly integrates fully automated sample preparation with LC-MS/MS instrumentation and computing servers, enabling direct generation of protein quantification data matrices from biospecimen samples without manual intervention [23]. Such automation significantly enhances reproducibility and throughput while reducing operational variability.

Chemical proteomics has rightfully earned its status as the gold standard for direct target fishing in natural product research. Its ability to experimentally validate protein targets within biologically relevant systems provides an unequivocal advantage over purely computational predictions. The methodology's unique capacity to identify multiple targets simultaneously offers crucial insights into the polypharmacology that often underlies the efficacy of natural products [20] [11].

While newer computational approaches like CTAPred demonstrate promising capabilities for predicting protein targets based on chemical similarity [10], they ultimately require experimental validation through methods like chemical proteomics to confirm biological relevance. The integration of chemical proteomics with emerging technologies—including automated platforms [23], advanced label-free methods [22], and AI-driven predictive tools [24]—creates a powerful synergy that accelerates the drug discovery process while maintaining rigorous experimental validation.

For researchers investigating natural product mechanisms, chemical proteomics provides the most direct and comprehensive approach for target identification, offering unparalleled insights into the complex interactions between small molecules and biological systems that underlie therapeutic efficacy.

In the field of natural product research and drug discovery, identifying the molecular targets of bioactive compounds is a critical step in understanding their mechanism of action. Target identification and validation have been significantly advanced by chemical biology strategies that employ designed molecular probes. These probes enable researchers to capture, isolate, and identify proteins that interact with small molecules in complex biological systems. Among the most powerful approaches are those utilizing biotin labels, alkyne/azide click chemistry, and photoaffinity groups, which can be used individually or in combination to create sophisticated tools for target deconvolution. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these strategies, their optimal applications, and integrated experimental protocols to assist researchers in selecting the most appropriate methodology for their specific research needs.

Core Components of Effective Probe Design

Photoreactive Groups for Target Capture

Photoaffinity labeling (PAL) enables the covalent capture of typically transient protein-ligand interactions through light-activated chemistry. An effective photoaffinity probe incorporates three key functionalities: an affinity/specificity unit (the bioactive compound), a photoreactive moiety, and an identification/reporter tag [25]. The most commonly employed photoreactive groups in probe design each present distinct advantages and limitations, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Photoreactive Groups Used in Probe Design

| Photoreactive Group | Reactive Intermediate | Activation Wavelength | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzophenone (BP) | Triplet diradical | 350-365 nm | High selectivity for methionine; can be reactivated repeatedly; stable under ambient light [26]. | Bulky structure may cause steric hindrance; requires longer irradiation times, potentially increasing non-specific labeling [25] [26]. |

| Aryl Diazirine (DA) | Carbene | ~350 nm | Small size minimizes steric interference; highly reactive carbene intermediate forms stable cross-links rapidly; superior photophysical properties compared to aryl azides [25] [26]. | Can be less stable than other groups; the generated carbene has a very short half-life (nanoseconds) [25] [26]. |

| Aryl Azide (AA) | Nitrene | 254-400 nm | Relatively easy to synthesize and commercially available; chemically stable in the dark [25] [26]. | Requires shorter UV wavelengths that can damage biomolecules; nitrene intermediate can rearrange into less reactive side products, lowering yield [25]. |

The selection of an appropriate photoreactive group depends on the specific experimental requirements. Diazirines are often preferred for their small size and high reactivity, which is critical for capturing weak or transient interactions [25]. Benzophenones are valuable when precise control over the crosslinking event is needed, thanks to their activatability with longer, less damaging wavelengths of UV light and their ability to be reactivated [26]. Aryl azides offer a cost-effective and synthetically accessible entry into photoaffinity labeling, though their potential for side reactions must be considered [25].

Detection and Enrichment Tags

Following covalent capture, the protein-probe adduct must be detected and isolated from a complex biological mixture. This is typically achieved using a reporter tag.

- Biotin: This is the most widely used reporter group due to the strong, nearly irreversible interaction (Kd ∼ 10⁻¹⁵ mol/L) between biotin and streptavidin/avidin proteins [27]. This interaction allows for powerful enrichment of probe-bound proteins from complex lysates using streptavidin-coated beads. However, this very strength makes elution of intact proteins challenging, often requiring harsh denaturing conditions that can co-elute contaminants [27].

- Cleavable Biotin Probes: To overcome elution challenges, cleavable linkers can be incorporated between biotin and the probe. These allow for mild, specific release of captured proteins, significantly reducing background and improving the purity of samples for downstream mass spectrometry analysis [27]. Various cleavage strategies are available, as detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Comparison of Cleavable Linker Strategies for Biotin Probes

| Cleavage Method | Cleavage Trigger | Cleavage Conditions | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dialkoxydiphenylsilane (DADPS) | Acid | 10% Formic Acid, 0.5 hours [27]. | Highly efficient cleavage under mild acidic conditions; leaves a small (143 Da) mass tag on the protein [27]. |

| Disulfide | Reduction | Dithiothreitol (DTT) or Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) [27]. | Standard reduction method; requires careful handling to prevent premature cleavage. |

| Diazobenzene | Reduction | Sodium Dithionite (Na₂S₂O₄) [27]. | A specific chemical reduction trigger. |

| Photocleavable Linker | UV Light | Irradiation at 365 nm [27]. | Provides a physical (non-chemical) trigger for cleavage. |

Bioorthogonal Handles for Versatile Tagging