Systems Metabolic Engineering: Advanced Strategies for High-Yield Natural Product Synthesis

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary systems metabolic engineering strategies for the overproduction of pharmaceutically significant natural products.

Systems Metabolic Engineering: Advanced Strategies for High-Yield Natural Product Synthesis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary systems metabolic engineering strategies for the overproduction of pharmaceutically significant natural products. It synthesizes foundational concepts, cutting-edge methodological tools like CRISPR/Cas9 and genome-scale modeling, systematic troubleshooting for pathway optimization, and rigorous validation frameworks. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content bridges the gap between laboratory-scale success and industrially viable bioprocesses, offering a roadmap for developing efficient microbial cell factories to meet the growing demand for complex therapeutic compounds.

The Foundation of Microbial Factories: Principles and Host Selection for Natural Product Synthesis

Defining Metabolic Engineering and Its Role in Modern Biotechnology

Metabolic engineering is the science of rewiring cellular metabolism to enhance the production of valuable chemicals, materials, and pharmaceuticals from renewable resources [1] [2]. It transforms microorganisms into efficient "cell factories" by modifying specific biochemical reactions or introducing new genes using recombinant DNA technology [1]. This field has become a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, enabling sustainable alternatives to traditional petroleum-based refining for products ranging from biofuels to life-saving drugs [1] [3].

The field operates through iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles, mirroring approaches from computational and engineering sciences to systematically optimize complex biological systems [2]. For researchers focused on natural product overproduction, metabolic engineering provides powerful tools to overcome the low yields and high costs often associated with extracting these compounds from native plant sources [3] [4].

The Evolution and Core Principles of Metabolic Engineering

The Three Waves of Metabolic Engineering

The field has evolved through distinct technological waves, each bringing new capabilities:

- First Wave (1990s): Relied on rational approaches to pathway analysis and flux optimization. A classic example is the overproduction of lysine in Corynebacterium glutamicum, where identifying and alleviating metabolic bottlenecks led to a 150% increase in productivity [1].

- Second Wave (2000s): Incorporated systems biology and genome-scale metabolic models to understand metabolic networks at a systemic level. This allowed for predicting genotype-phenotype relationships and identifying gene knockout targets for enhanced production [1].

- Third Wave (2010s-present): Integrated synthetic biology tools to design, construct, and optimize complete heterologous pathways for natural and non-natural chemicals. This wave began with pioneering work on artemisinin production and continues to expand the array of attainable products [1].

Hierarchical Engineering Strategies

Modern metabolic engineering employs strategies at multiple biological hierarchies to rewire cellular metabolism effectively [1]:

- Part Level: Engineering individual enzymes for improved catalytic efficiency or specificity.

- Pathway Level: Assembling and optimizing multi-enzyme pathways for converting substrates to desired products.

- Network Level: Modulating regulatory networks and cofactor balances to support pathway flux.

- Genome Level: Implementing genome-scale edits to remove competing pathways or introduce new capabilities.

- Cell Level: Engineering cellular physiology, including transport and tolerance mechanisms.

The relationship between these strategies and the DBTL cycle can be visualized as follows:

Troubleshooting Common Metabolic Engineering Challenges

Low Product Titer Despite Pathway Integration

Problem: Engineered strains show successful gene integration but produce disappointingly low levels of the target natural product.

Diagnosis Guide:

- Check for metabolic flux imbalances where intermediates may accumulate or drain away from your desired pathway [2].

- Identify potential bottleneck enzymes with low catalytic efficiency or poor expression in your host [1].

- Assess whether toxicity from intermediates or products is inhibiting cell growth and production [2].

- Verify that essential cofactors (NADPH, ATP) are sufficiently available to drive biosynthesis [1].

Solutions:

- Enzyme Engineering: Improve catalytic efficiency through directed evolution or rational design [1].

- Cofactor Balancing: Introduce transhydrogenases or modify carbon flux to regenerate NADPH [1].

- Promoter Optimization: Fine-tune expression levels using promoter libraries to balance pathway flux [1].

- Compartmentalization: Target pathway enzymes to specific subcellular locations (mitochondria, chloroplasts) to isolate toxic intermediates and pool precursors [4] [5].

Experimental Protocol: Metabolite Profiling for Flux Analysis

- Cultivate engineered strain in controlled bioreactor conditions

- Collect samples at multiple time points during growth and production phases

- Quench metabolism rapidly using cold methanol (-40°C)

- Extract intracellular metabolites using 40:40:20 acetonitrile:methanol:water

- Analyze intermediates via LC-MS/MS with appropriate standards

- Calculate flux ratios using isotopomer distribution from 13C-labeled glucose feeding experiments

- Identify nodes with significant metabolite pooling or drain

Host Viability Issues Post-Engineering

Problem: Engineered strains exhibit poor growth or genetic instability, particularly when introducing complex heterologous pathways.

Diagnosis Guide:

- Determine if the issue stems from metabolic burden due to resource diversion for heterologous protein expression [2].

- Test for toxicity of pathway intermediates that may accumulate due to enzyme mismatches [5].

- Check for energy depletion if ATP-intensive pathways were introduced without compensatory engineering [2].

- Verify genetic stability through plasmid loss assays or genome sequencing to detect mutations.

Solutions:

- Dynamic Regulation: Implement biosensor-regulated circuits that decouple growth and production phases [2].

- Genome Integration: Stably integrate pathway genes into the host genome rather than using plasmid-based expression [1].

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution: Passage strains under selective pressure to restore fitness while maintaining production [6].

- Tolerance Engineering: Pre-adapt hosts to products or intermediates through gradual exposure [3].

Research Reagent Solutions for Host Engineering:

| Reagent/Category | Example Applications | Function in Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Gene knockouts, transcriptional regulation | Precise genome editing for pathway installation and regulatory manipulation [6] [5] |

| Biosensors | Malonyl-CoA, metabolite-responsive regulators | Dynamic pathway control and high-throughput screening [3] |

| Terminator Libraries | mRNA stability optimization | Fine-tuning gene expression levels [1] |

| Subcellular Targeting Tags | Chloroplast, peroxisome, endoplasmic reticulum localization | Compartmentalizing pathways to isolate toxic intermediates [3] [5] |

| Genome-Scale Models | E. coli iJR904, S. cerevisiae iMM904 | Predicting metabolic fluxes and identifying engineering targets [1] [7] |

Poor Scale-Up Performance

Problem: Strains performing well in laboratory flasks show decreased productivity in bioreactor conditions.

Diagnosis Guide:

- Identify heterogeneity in large-scale cultures where nutrient gradients create subpopulations [2].

- Check for mass transfer limitations of oxygen or nutrients in dense cultures [8].

- Assess shear stress sensitivity from impeller mixing in large bioreactors.

- Monitor for quorum sensing or cross-talk that emerges at high cell densities.

Solutions:

- Strain Robustness Engineering: Use transcriptomic profiling to identify scale-up stress responses and engineer tolerance [3].

- Process Control Optimization: Implement advanced control strategies for dissolved oxygen, pH, and feeding regimes [8].

- Morphology Engineering: Modify cellular morphology to reduce broth viscosity and improve mixing [3].

Experimental Protocol: Scale-Down Reactor Experiments

- Use laboratory-scale bioreactors with oscillating conditions to simulate industrial-scale gradients

- Program cyclic variations in dissolved oxygen (0-100% over 1-5 minute cycles)

- Implement pulsed nutrient feeding to create feast-famine conditions

- Sample frequently to assess metabolic state (ATP, NADH/NAD+ ratios)

- Analyze population heterogeneity using flow cytometry

- Isolate robust variants that maintain production under oscillating conditions

Platform Selection and Pathway Optimization

Choosing the Right Production Platform

Selecting an appropriate host organism is critical for successful overproduction of natural products. Each platform offers distinct advantages and limitations:

Comparative Analysis of Production Platforms:

| Platform | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Ideal Natural Product Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Medicinal Plants | Native enzymatic context for complex modifications; pre-existing storage structures [4] [5] | Long growth cycles; low yields; complex genetics; ecological concerns [5] | High-value compounds already produced by the plant; molecules requiring extensive plant-specific modifications [5] |

| Microbial Chassis (E. coli, S. cerevisiae) | Rapid growth & high cell density; well-established genetic tools; scalable fermentation [1] [3] [2] | Cytotoxicity of intermediates; lack of specific P450s/UGTs; cofactor balancing issues [5] | Volatile mono/sesquiterpenes; triterpene scaffolds; non-natural derivatives [5] |

| Heterologous Plant Hosts (N. benthamiana) | Eukaryotic PTMs and compartmentalization; low-cost biomass production; capable of complex pathways [4] [5] | Transient expression limitations; metabolic competition; scale-up challenges for extraction [4] [5] | Complex diterpenes/triterpenes; molecules requiring plant-specific P450s/UGTs; rapid pathway prototyping [5] |

| Oleaginous Yeasts (Y. lipolytica) | High flux through pentose phosphate pathway; native lipid accumulation; industrial safety [2] | Limited genetic tools compared to model systems; fewer omics resources available [2] | Acetyl-CoA-derived compounds; fatty acid-derived natural products; lipophilic compounds [2] |

Computational Tools for Strain Design

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and related constraint-based modeling approaches enable quantitative prediction of metabolic behavior after genetic modifications [7]. The core principle involves solving for steady-state flux distributions that satisfy mass balance constraints:

Algorithmic Strain Design: Tools like OptORF use bilevel mixed integer linear programming to identify optimal gene knockout strategies that maximize chemical production while maintaining cellular growth [7]. These algorithms incorporate Gene-Protein-Reaction associations to model how genetic changes propagate through metabolic networks.

FAQs: Addressing Critical Metabolic Engineering Questions

Q: How can I balance metabolic flux when engineering complex plant pathways in microbial hosts?

A: Implement modular pathway engineering with tunable intermodular expression:

- Divide the pathway into logically connected modules (e.g., upstream precursor supply, midstream core pathway, downstream modification)

- Use promoter libraries or ribosomal binding site variants to balance expression within modules

- Employ biosensors to dynamically regulate flux in response to intermediate accumulation

- Consider spatial organization via protein scaffolds or compartmentalization [1] [3]

Q: What strategies exist for handling cytotoxic intermediates in heterologous pathways?

A: Multiple approaches can mitigate cytotoxicity:

- Transport Engineering: Export toxic compounds from the cytosol [3]

- Enzyme Fusion: Channel intermediates directly between active sites to minimize release [1]

- Vacuolar Sequestration: Engineer storage of toxic compounds in membrane-bound organelles [3]

- Immediate Conversion: Ensure rapid conversion of toxic intermediates by pairing enzymes with matched kinetics [5]

Q: How can I improve electron transfer efficiency for P450-dependent reactions in microbial hosts?

A: P450s often require specific redox partners that may not function optimally in heterologous hosts:

- Couple with compatible redox partners from phylogenetically related organisms

- Engineer fusion proteins between P450s and their reductase domains

- Implement cofactor regeneration systems to maintain NADPH pools

- Utilize artificial electron transfer systems using ferredoxin-ferredoxin reductase pairs [5]

Q: What are the current best practices for scaling up natural product production from engineered strains?

A: Successful scale-up requires integrated bioprocess engineering:

- Use scale-down models to identify potential limitations early

- Implement dynamic feeding strategies based on real-time metabolite monitoring

- Engineer host robustness against industrial stress conditions (osmolality, shear stress)

- Employ in situ product removal techniques to alleviate feedback inhibition [3] [8]

Metabolic engineering has matured into a powerful discipline for the sustainable production of natural products, enabled by increasingly sophisticated tools for pathway design, host engineering, and process optimization. The integration of systems biology, synthetic biology, and machine learning continues to accelerate the DBTL cycle, reducing development timelines for novel cell factories [1] [6].

Future advancements will likely focus on automated strain construction platforms, machine learning-guided pathway design, and photoautotrophic production systems that utilize CO₂ as a carbon source [6] [5]. For researchers troubleshooting metabolic engineering challenges, the key lies in systematically addressing bottlenecks at multiple hierarchical levels—from enzyme kinetics to cellular physiology and bioprocess parameters—while leveraging the growing toolkit of computational and experimental resources.

The Critical Importance of Natural Products in Drug Discovery and Development

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Metabolic Engineering Experiments

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers and scientists in overcoming common experimental challenges in metabolic engineering for the overproduction of natural products. The guides below provide targeted solutions for issues related to low product yields, host viability, and analytical characterization.

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Product Yield in Microbial Hosts

Problem: Your engineered microbial strain shows poor production titers of the target natural product, despite a successfully inserted biosynthetic pathway.

| Observed Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low final product titer, poor cell growth | Precursor Limitation: Central metabolic flux not directed toward your pathway's building blocks. | Measure intracellular concentrations of key precursors (e.g., acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA). Analyze transcriptome data for expression of precursor biosynthesis genes [9]. | Overexpress key enzymes in precursor supply pathways (e.g., ACC for malonyl-CoA). Engineer cofactor supply (e.g., NADPH) [9] [10]. |

| Accumulation of pathway intermediates, low final product | Rate-Limiting Enzyme: A slow step in the biosynthetic pathway creates a bottleneck. | Quantify intermediate metabolites using LC-MS. Measure in vitro activity of individual pathway enzymes [11]. | Overexpress the suspected low-activity enzyme. Use a promoter library to fine-tune the expression levels of all pathway genes for balance [12]. |

| High product yield initially, then decline in production | Product Toxicity: The natural product or an intermediate inhibits cell growth or pathway function. | Monitor cell growth and product titer over time in batch culture. Test for growth inhibition by adding pure product to culture [9]. | Engineer product export systems. Implement in situ product removal (ISPR) from the bioreactor. Degrade or modify the toxic compound [9]. |

| Unstable production over generations | Genetic Instability: The engineered pathway is lost or silenced over time due to plasmid instability or metabolic burden. | Plate cells on selective and non-selective media to check for plasmid loss. Sequence the pathway region after multiple generations [10]. | Integrate the pathway into the host genome. Use stable, low-copy-number plasmids. Employ genomic elements (e.g., BGC) that enhance stability [13]. |

| Inefficient pathway in heterologous host | Incompatible Host Physiology: The host lacks necessary post-translational modifications, chaperones, or cofactors. | Check for activity of essential auxiliary proteins (e.g., PPTase for PKS/NRPS pathways). Conduct proteomics to see if pathway proteins are properly expressed [10]. | Engineer host physiology (e.g., co-express necessary accessory proteins like Sfp PPTase). Consider switching to a more compatible host (e.g., Streptomyces for actinomycete-derived pathways) [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: We transferred a full biosynthetic gene cluster into E. coli, but no product is detected. What are the first things to check?

This is a common challenge in heterologous expression. Follow this diagnostic workflow:

- Step 1 - Confirm Genetic Construct: Verify the sequence integrity of the entire cluster via sequencing. Ensure that all genes, including those for regulatory functions and resistance, are present and correctly assembled [10].

- Step 2 - Check Gene Expression: Use RT-PCR or RNA-Seq to confirm that all genes in the cluster are being transcribed. The absence of transcription points to a problem with the promoter or a missing regulatory gene [13].

- Step 3 - Verify Protein Expression: Conduct a Western blot (if antibodies are available) or use tagged proteins to confirm that the key large enzymes (e.g., PKS, NRPS) are being synthesized in full-length, soluble form [10].

- Step 4 - Assess Host Compatibility: Many natural product pathways require specific host factors. A critical check is for phosphopantetheinylation, a essential activation step for PKS and NRPS enzymes. Co-express a broad-spectrum phosphopantetheinyl transferase (e.g., sfp) if your host lacks one [10].

FAQ 2: Our strain produces the desired natural product, but the yields are too low for commercial feasibility. What strategies can we use for systematic improvement?

Low yield is a multi-faceted problem. Modern metabolic engineering employs a combination of strategies, often summarized by the multivariate modular metabolic engineering (MMME) approach [12]. Instead of optimizing single genes, MMME treats the pathway as a set of modules (e.g., a precursor supply module and a biosynthetic module). You can then optimize the expression of each module as a unit, reducing the combinatorial complexity of the experiment. Key strategies include:

- Enhance Precursor Supply: Engineer central carbon metabolism to increase the flux toward key precursors like acetyl-CoA or malonyl-CoA. This can involve overexpressing key genes, deleting competing pathways, and balancing cofactors [9] [10].

- Engineer Cell Physiology: For hydrophobic natural products that accumulate intracellularly, this can cause toxicity and feedback inhibition. Engineer the cell membrane or create intracellular storage compartments like lipid bodies to enhance storage and tolerance [9].

- Apply High-Throughput Screening: If your product has no easy assay, develop a biosensor—a genetic circuit that links product concentration to a measurable output like fluorescence. This allows you to screen vast libraries of engineered strains or enzyme variants for high producers [9].

FAQ 3: How can we rapidly identify the structure of novel natural products or unexpected derivatives produced by our engineered strain?

Advances in analytical chemistry have greatly accelerated this process.

- LC-HRMS: Liquid Chromatography coupled to High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry is the cornerstone. It provides the exact mass of the compound and its fragments, allowing you to propose a molecular formula and compare it to databases [14].

- Molecular Networking: This is a powerful bioinformatic technique used with LC-MS/MS data. It visualizes the chemical space of your sample as a network where similar spectra cluster together. This quickly identifies known compounds and highlights novel derivatives that are structurally related to your target, guiding purification efforts [14].

- NMR Spectroscopy: While requiring purification, NMR remains the gold standard for determining the planar structure and stereochemistry of an unknown compound. Hyphenated techniques like LC-SPE-NMR can streamline the process from separation to structure elucidation [14].

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering

The following table lists essential materials and tools frequently used in advanced metabolic engineering projects for natural product production.

| Research Reagent | Function in Metabolic Engineering | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Broad-Host-Range PPTase (e.g., Sfp) | Activates carrier proteins in PKS and NRPS pathways by attaching a phosphopantetheine arm, essential for enzyme function [10]. | Essential for producing polyketides like 6-deoxyerythronolide B (6dEB) in E. coli, which lacks a native PPTase with broad specificity [10]. |

| Biosensors | Genetic circuits that detect an intracellular metabolite and output a measurable signal (e.g., fluorescence). Enable high-throughput screening of mutant libraries [9]. | Screening for overproduction of malonyl-CoA-derived products; a biosensor for a target molecule can rapidly identify high-producing strains from thousands of variants [9]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Computational models that simulate the entire metabolic network of an organism. Predict the outcome of genetic manipulations on growth and product yield [15]. | Identify gene knockout targets that maximize flux toward a natural product precursor while minimizing byproducts, guiding rational strain design. |

| Module Promoter Library | A collection of promoters of varying strengths used to control the expression of entire functional modules of a pathway (e.g., precursor module, elongation module) [12]. | Implementing MMME to balance flux in a terpenoid biosynthetic pathway, leading to a 1,000-fold increase in product titer [12]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Troubleshooting Low Yield

This protocol provides a systematic, iterative methodology for diagnosing and resolving low production yields in an engineered host.

1. Define the Problem Quantitatively: * Measure the baseline titer, yield, and productivity of your strain under controlled fermentation conditions. * Use analytical methods like HPLC or LC-MS to quantify the final product and any detectable pathway intermediates [14].

2. Map the Pathway and Formulate Hypotheses: * Construct a detailed diagram of the biosynthetic pathway, including all genes, enzymes, precursors, and cofactors. * Based on the symptoms (see Troubleshooting Guide), formulate testable hypotheses for the bottleneck (e.g., "Flux through enzyme X is limiting").

3. Design and Execute Diagnostic Experiments: * Test Precursor Availability: Feed labeled (e.g., ¹³C) substrates and use flux analysis to track carbon movement through central metabolism into your pathway [15]. * Profile Metabolites: Use LC-MS/MS to quantify intermediates. The point where an intermediate accumulates indicates the next step may be rate-limiting [11]. * Assay Enzyme Activities: Perform in vitro assays on cell lysates to measure the catalytic rate of key enzymes compared to the flux demand [11].

4. Implement a Genetic Intervention: * Based on your findings, choose an intervention (e.g., overexpress a bottleneck enzyme, delete a competing pathway, integrate a biosensor). * Use standardized genetic tools (e.g., CRISPR, plasmid systems) to make the change.

5. Evaluate the Outcome and Iterate: * Re-measure the production metrics and cell fitness of the new strain. * Compare the results to your previous baseline. If the problem is not resolved, return to Step 2 with new data and formulate a new hypothesis.

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of this troubleshooting protocol.

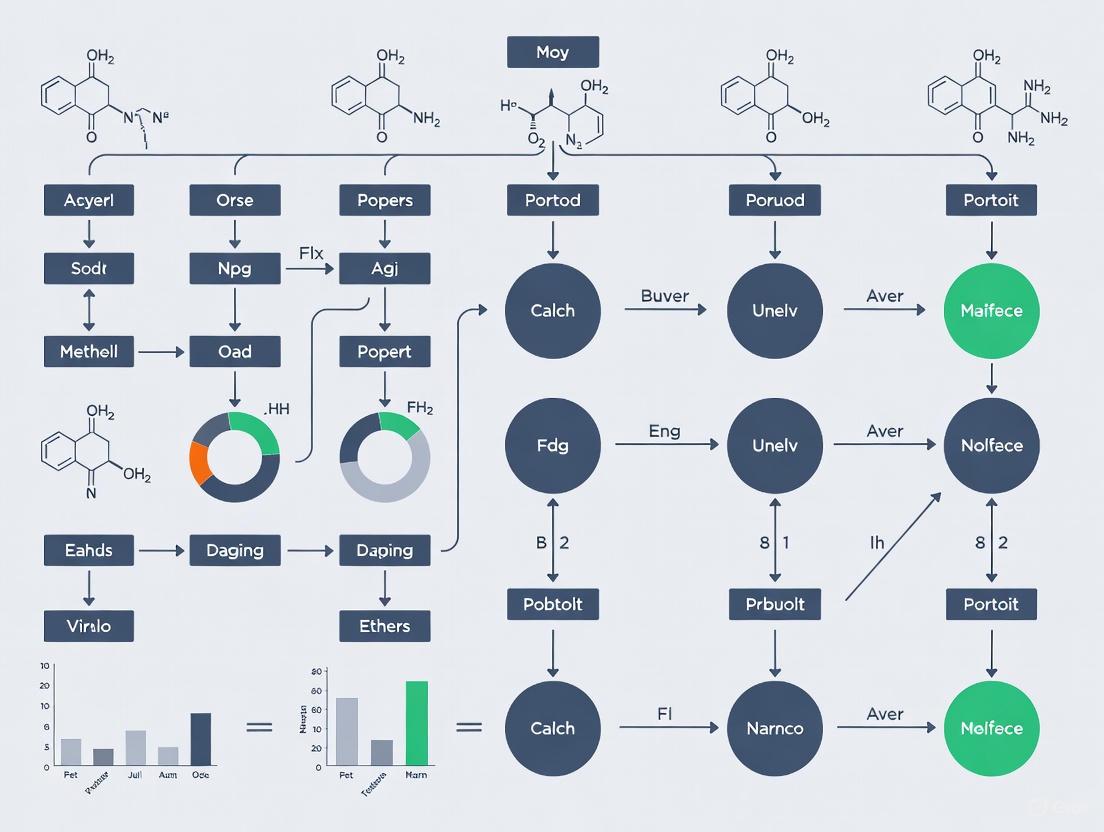

A Modular Engineering Workflow for Natural Product Pathways

The MMME strategy has proven highly successful for engineering complex pathways. It involves redefining the metabolic network into co-regulated modules and optimizing the expression of these modules relative to one another. This approach was famously used to achieve high-level production of the taxadiene precursor of Taxol in E. coli [12]. The following diagram outlines the core concept.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: Our engineered microbial host shows low yield of a target natural product, such as a polyketide. What are the primary metabolic bottlenecks we should investigate?

A: Low yields in natural product synthesis often stem from bottlenecks in core metabolism. The primary areas to investigate are:

- Precursor and Cofactor Supply: The synthesis of most natural products, including polyketides and non-ribosomal peptides, requires precursors like acetyl-CoA and reducing power (NADPH). Insufficient flux through glycolysis or the TCA cycle can starve the pathway. Implement modular pathway engineering to balance the flux and enhance precursor supply [1].

- Enzyme Incompatibility: Chimeric modular enzymes (PKS/NRPS) may have poor activity due to inter-modular incompatibility. Consider engineering synthetic interfaces (e.g., docking domains, SpyTag/SpyCatcher) to ensure efficient substrate channeling between non-native enzyme modules [16].

- Cellular Energy Redirection: The host's native metabolism may prioritize growth over product formation. Rewiring central carbon metabolism, for instance by creating a synthetic cytosolic reductive pathway, can enhance the supply of energy and reducing power specifically for biosynthesis [17].

Q2: How can we rapidly prototype and test the functionality of a newly discovered biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) without lengthy genetic modification?

A: Cell-free synthetic biology (CFE) systems are ideal for rapid prototyping.

- Approach: Express the target BGC in a cell-free transcription-translation system. This eliminates the constraints of cell walls, membranes, and genomic context, allowing for direct control of the reaction environment [18].

- Benefits: This method enables rapid cycling between design and analysis (hours versus days/weeks for cell-based methods). It is particularly useful for characterizing "cryptic" or "silent" BGCs and detecting toxic or unstable intermediates that are difficult to observe in whole cells [18].

Q3: We observe an imbalance in the α-ketoglutarate (αKG)/succinate ratio during fermentation. How can this impact production, and how can it be managed?

A: The αKG/succinate ratio is a critical metabolic node with dual bioenergetic and epigenetic roles.

- Impact: αKG is a co-factor for αKG-dependent dioxygenases, which include chromatin-modifying enzymes. An increased αKG/succinate ratio can stimulate differentiation processes in certain cell types, potentially diverting resources away from proliferation and product synthesis [19].

- Management: In a microbial context, this ratio can be managed through metabolic engineering. Strategies include modulating the expression of TCA cycle enzymes like 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) or introducing synthetic pathways that alter the carbon flux around this node to maintain a ratio optimal for your production goals [19] [17].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantitative Assessment of Glycolytic and TCA Cycle Fluxes using Stable Isotope Tracing

This protocol is adapted from established methods for mapping central carbon metabolism in microbial systems [20].

1. Principle: Cells are fed a stable isotope-labeled substrate (e.g., 13C6-glucose or 13C5-glutamine). The subsequent incorporation of the labeled carbon into downstream metabolites (e.g., pyruvate, lactate, TCA cycle intermediates) is tracked using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The resulting labeling patterns allow for the quantification of metabolic flux.

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Cultivation and Labeling. Grow the engineered microbial culture (e.g., yeast [20] [17] or E. coli [1]) to the desired growth phase. Rapidly switch the medium to one containing the 13C-labeled substrate.

- Step 2: Metabolite Quenching and Extraction. At specific time points post-labeling (e.g., 0, 1, 5, 15 minutes), rapidly quench metabolism (e.g., using cold methanol). Extract intracellular metabolites.

- Step 3: LC-MS/MS Analysis. Analyze the metabolite extracts using LC-MS/MS. Key metabolites to monitor include glucose-6-phosphate, fructose-6-phosphate, pyruvate, lactate, acetyl-CoA, citrate, α-ketoglutarate, succinate, and malate.

- Step 4: Data Analysis and Flux Calculation. Use specialized software (e.g., IsoSim, INCA) to model the metabolic network and calculate the fluxes that best fit the observed mass isotopomer distribution data.

Protocol: Engineering Modular Enzyme Assembly using Synthetic Interfaces

This protocol outlines a DBTL (Design-Build-Test-Learn) cycle for re-engineering PKS/NRPS assembly lines [16].

1. Principle: Replace natural docking domains between megasynthase modules with standardized synthetic interfaces (e.g., coiled-coils, SpyTag/SpyCatcher) to create functional chimeric enzymes for novel natural product biosynthesis.

2. Procedure:

- Design Phase: Deconstruct the target novel natural product structure into potential PKS/NRPS modules. Select well-characterized synthetic interfaces known to facilitate protein-protein interactions orthogonally.

- Build Phase: Combinatorially assemble gene constructs encoding the selected modules fused with the synthetic interface parts. Automation-assisted cloning is recommended for high-throughput assembly.

- Test Phase: Heterologously express the chimeric constructs in a suitable host (e.g., Streptomyces). Analyze the metabolic output for the production of the target compound and any shunt products using analytical chemistry (e.g., LC-MS).

- Learn Phase: Use the experimental data to train AI/models (e.g., Graph Neural Networks) to predict the compatibility of modules and optimize the design of synthetic linkers for the next DBTL cycle.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Production of Selected Chemicals

This table summarizes successful metabolic engineering interventions in core pathways for the overproduction of various chemicals, as referenced in the literature [1].

| Chemical | Host Organism | Titer/Yield/Productivity | Key Metabolic Engineering Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysine | Corynebacterium glutamicum | 223.4 g/L, 0.68 g/g glucose | Cofactor & Transporter engineering; Promoter engineering [1] |

| 3-Hydroxypropionic Acid | C. glutamicum | 62.6 g/L, 0.51 g/g glucose | Substrate engineering; Genome editing [1] |

| Succinic Acid | E. coli | 153.36 g/L, 2.13 g/L/h | Modular pathway engineering; High-throughput genome engineering [1] |

| Free Fatty Acids | S. cerevisiae | 40% of theoretical yield | Implementation of a synthetic cytosolic reductive (decarboxylation) cycle [17] |

| Muconic Acid | C. glutamicum | 54 g/L, 0.34 g/L/h | Modular pathway engineering; Chassis engineering [1] |

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents and tools for metabolic engineering experiments focused on core pathways and natural product synthesis.

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Substrates (e.g., 13C-Glucose) | Tracers for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes via LC-MS/MS | Mapping glycolytic and TCA cycle fluxes in engineered yeasts [20] |

| Synthetic Protein Interfaces (e.g., SpyTag/SpyCatcher) | Genetically encoded protein ligation tool for post-translational complex formation | Engineering chimeric PKS/NRPS modules for novel natural product assembly [16] |

| Cell-Free Expression (CFE) System | In vitro transcription-translation system for rapid pathway prototyping | Expressing and characterizing cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters without cellular constraints [18] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational models simulating organism-wide metabolism | Predicting gene knockout/knockdown targets for optimizing product yield [1] |

| Inducible shRNA System | Allows for tunable, reversible gene knockdown in vivo | Studying the role of specific metabolic enzymes (e.g., OGDH) in cell fate and metabolism [19] |

| Necrostatin-5 | Necrostatin-5, CAS:337349-54-9, MF:C19H17N3O2S2, MW:383.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Methyl-1-acetoxycalix[6]arene | 4-Methyl-1-acetoxycalix[6]arene, CAS:141137-71-5, MF:C60H60O12, MW:973.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle

Synthetic Reductive Metabolism

In metabolic engineering for the overproduction of natural products (NPs), selecting an appropriate production host is a foundational decision that significantly impacts the success and efficiency of the research and development process. The optimal host provides the necessary genetic, enzymatic, and physiological background to support the often complex and metabolically demanding biosynthetic pathways. Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and various Actinomycetes (notably Streptomyces species) represent the most widely utilized and characterized hosts [10] [21] [22]. This guide provides a technical support framework to help researchers navigate the selection, optimization, and troubleshooting of these host systems for NP overproduction.

Host Comparison Tables

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Production Hosts

| Feature | E. coli | S. cerevisiae | Actinomycetes (e.g., Streptomyces) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organism Type | Gram-negative bacterium | Unicellular fungus (Yeast) | Gram-positive, filamentous bacteria |

| Genetic Tractability | High; very easy and fast genetic manipulation [10] | High; well-established genetic tools [23] | Moderate to low; genetically challenging but tools are improving [24] [21] |

| Growth Speed | Very fast (doubling time ~20 min) [10] | Fast (doubling time ~90 min) | Slow (doubling time can be several hours) [21] |

| Native NP Potential | Low | Low | Very High; prolific producers of antibiotics and other NPs [24] [22] |

| Membrane Protein Production | Often results in inclusion bodies; requires refolding [23] | Superior for producing correctly folded, active integral membrane proteins [23] | N/A |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Limited (prokaryotic) | Eukaryotic (e.g., glycosylation) | Prokaryotic, with specialized modifications (e.g., phosphopantetheinylation) [10] |

| Key Advantage | Rapid cycling, vast toolkit, high yields for some compounds | Eukaryotic machinery, compartmentalization, GRAS status | Endogenous precursor supply and specialized enzymes for complex NP synthesis [10] [21] |

| Primary Challenge | Lack of native precursors for many NPs; toxic pathway intermediates | Correct folding of prokaryotic proteins; metabolic burden | Complex morphology, slow growth, genetic instability [24] [21] |

Table 2: Metabolic and Engineering Considerations

| Consideration | E. coli | S. cerevisiae | Actinomycetes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred Carbon Source | Glucose, Glycerol | Glucose, Sucrose | Complex carbon sources (e.g., maltose, starch) |

| Common Precursor Supply | Requires engineering for malonyl-CoA, methylmalonyl-CoA, etc. [10] | Endogenous acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA | Endogenous supply of diverse CoA precursors (e.g., methylmalonyl-CoA) [10] |

| Example NP Success | Erythromycin precursor (6dEB) [10] | Various isoprenoids, cannabinoids | Streptomycin, Vancomycin, Daptomycin, Tetracycline [10] [22] |

| Ideal Use Case | Heterologous production of Type I PKS/NRPS products and other bacterial NPs with precursor engineering [10] | Eukaryotic NPs, membrane proteins, and long, complex pathways that benefit from compartmentalization | Heterologous production of actinomycete-derived NPs, especially those requiring type II PKS or complex post-assembly modifications [10] [21] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: When should I choose a heterologous host over the native producer? A heterologous host is advisable when the native producer is difficult to culture, genetically intractable, has a long growth period, or produces low native titers of the target compound. Heterologous hosts like E. coli and S. cerevisiae can offer faster growth, easier genetic manipulation, and the ability to decouple NP production from native regulation [10] [21]. Furthermore, transferring a pathway to a "clean" host that does not produce competing secondary metabolites can simplify purification and increase yield [10] [24].

FAQ 2: My biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) is not being expressed in the heterologous host. What are the first things I should check? Start with these fundamental checks:

- DNA Methylation and Restriction Systems: This is a major barrier. Identify the methylated motifs in your production host using SMRT sequencing and ensure your transforming DNA is protected with the corresponding methylation pattern to evade the host's restriction-modification systems [25].

- Promoter and Regulatory Elements: The native promoters from your BGC may not be recognized in the new host. Refactor the cluster by replacing native promoters with well-characterized, strong or inducible promoters specific to your chosen host (e.g., T7/lac in E. coli, GAL in S. cerevisiae, or constitutive ermE in Streptomyces) [24] [21].

- Codon Usage: Genes with high GC-content (common in actinomycetes) may be poorly expressed in low-GC hosts like E. coli and S. cerevisiae. Consider codon optimization for the heterologous host [24].

- Essential Pathway Components: Ensure all necessary enzymes are present. For polyketide or nonribosomal peptide production, this includes not only the large synthases (PKS/NRPS) but also essential tailoring enzymes and a phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) to activate carrier proteins [10] [22].

FAQ 3: What are the key advantages of using an engineered Actinomycete as a heterologous host? Engineered Streptomyces hosts (e.g., S. coelicolor CH999 or S. lividans K4-114) offer several key advantages for expressing actinomycete-derived BGCs:

- Physiological Compatibility: They are pre-adapted to produce the necessary precursors (e.g., methylmalonyl-CoA) and possess the cellular machinery to correctly process and modify complex bacterial enzymes like type II PKSs, which can be difficult to express in E. coli [10].

- Clean Background: These strains have their native antibiotic BGCs knocked out, reducing metabolic competition for precursors and simplifying the purification of the target compound [10] [24].

- Utilization of Optimized Industrial Strains: Transferring a BGC into an industrial strain already optimized for high-level secondary metabolite production can be a shortcut to achieving high titers [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Titer of Target Natural Product

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low yield in native actinomycete producer. | Tight native regulation; cryptic pathway. | Delete pathway-specific repressors or overexpress activators [24]. Use chemical elicitors or co-culture to activate silent clusters. |

| Low yield in heterologous host (E. coli or S. cerevisiae). | Insufficient precursor supply. | Engineer precursor pathways: overexpress acetyl-CoA carboxylase for malonyl-CoA, propionyl-CoA carboxylase for (2S)-methylmalonyl-CoA [10]. Knock out competing pathways (e.g., propionate catabolism) [10]. |

| Low yield in heterologous host. | Metabolic burden or toxicity. | Use a tunable expression system (e.g., inducible promoters) to express the BGC after sufficient biomass is generated. |

| Accumulation of intermediates, not final product. | Bottleneck in the biosynthetic pathway. | Identify and overexpress rate-limiting enzymes or missing tailoring enzymes (e.g., hydroxylases, glycosyltransferases). |

| Unstable heterologous DNA in actinomycetes. | High GC-content and repetitive sequences in BGCs. | Use direct pathway cloning (DiPaC) or iCatch methods designed for high-GC DNA [24]. Use stable replicating vectors or integrate the BGC into the host chromosome. |

Problem: Difficulty with Genetic Manipulation

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low transformation efficiency in actinomycetes. | Restriction-Modification (RM) systems degrading foreign DNA. | In vitro methylate the transforming DNA using E. coli strains that express methylases (e.g., dam/dcm). Identify the host's methylation motif via SMRT sequencing and methylate your DNA accordingly [25]. |

| Inefficient gene editing in any host. | Low recombination efficiency or persistence of wild-type allele. | Use CRISPR-Cas9 based tools for selection. For actinomycetes, deploy CRISPR tools developed for the specific genus to enable efficient gene knockouts and integrations [24] [21]. For E. coli, use scarless editing tools like iCASRED [26]. |

| Failure to clone large BGCs in E. coli. | Toxicity of gene products or instability of large inserts. | Use low-copy-number BAC vectors. Consider using an in vivo editing platform in E. coli (like iCASRED) that allows for scarless modification of the entire cluster after capture [26]. |

| Poor expression of a prokaryotic integral membrane protein in E. coli. | Misfolding and accumulation in inclusion bodies. | Switch to S. cerevisiae, which has a more advanced membrane protein biogenesis machinery and can rescue expression of functional proteins that fail in E. coli [23]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Heterologous Expression of a Polyketide Pathway in E. coli

This protocol outlines the key steps for producing a polyketide, such as the erythromycin precursor 6-deoxyerythronolide B (6dEB), in E. coli [10].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Propionyl-CoA Precursor Module: Genes pccA and pccB from S. coelicolor to convert propionyl-CoA to (2S)-methylmalonyl-CoA.

- PPTase: The sfp gene from Bacillus subtilis for post-translational activation of the acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains of the PKS.

- Propionate Utilization: Engineered host with deleted propionate catabolism pathway (prpE) and overexpressed propionyl-CoA ligase.

Methodology:

- Host Engineering: Create a base E. coli strain with the sfp PPTase gene integrated into the chromosome and the propionate catabolism pathway knocked out.

- Precursor Pathway: Introduce a plasmid expressing the pccA/pccB genes to enable synthesis of the (2S)-methylmalonyl-CoA extender unit.

- BGC Expression: Transform with a plasmid expressing the three large DEBS PKS genes (DEBS1, DEBS2, DEBS3).

- Fermentation and Analysis: Grow the engineered strain in a fed-batch fermenter with supplemented propionate. Analyze culture extracts for 6dEB production using LC-MS.

Protocol 2: Refactoring and Expressing a Silent BGC in a Streptomyces Heterologous Host

This protocol describes a strategy to activate a silent or poorly expressed BGC from a wild actinomycete isolate [24] [21].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cloning System: iCatch or Direct Pathway Cloning (DiPaC) for capturing large, high-GC BGCs.

- Refactoring Parts: A library of synthetic, well-characterized promoters (e.g., ermEp), RBSs, and terminators for Streptomyces.

- Conjugation Donor Strain: An E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 strain for transferring the constructed vector into the Streptomyces host via intergeneric conjugation.

Methodology:

- BGC Capture: Isolate the entire BGC from the native producer's gDNA using a method like DiPaC and clone it into an E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector [24].

- Refactoring: Replace all native promoters within the BGC with synthetic constitutive promoters to decouple expression from native regulation.

- Conjugation: Introduce the refactored BGC construct from the E. coli donor strain into the spores or mycelium of the engineered Streptomyces host (e.g., S. coelicolor M1152 or S. lividans K4-114).

- Screening and Fermentation: Select exconjugants and screen extracts for novel compound production using HPLC or metabolomic profiling (e.g., LC-MS/MS).

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Host Selection Decision Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical process for selecting an appropriate host for natural product production.

Diagram 2: E. coli Metabolic Engineering for Polyketide

This diagram shows the key genetic modifications needed for polyketide production in E. coli.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our engineered microbial host for a natural product shows good initial titers but poor long-term stability. What are the common causes? Strain instability often arises from regulatory bottlenecks or metabolic burden. To address this, consider these strategies:

- Dynamic Regulation: Implement metabolite-responsive biosensors to decouple growth and production phases, preventing toxicity from pathway intermediates [27].

- Eliminate Competitive Pathways: Use CRISPRi to repress genes responsible for byproduct formation that divert flux away from your target product [28].

- Transport Engineering: Overexpress specific exporters (e.g., BrnFE for branched-chain amino acids) to secrete the final product, reducing feedback inhibition and cellular toxicity [29].

Q2: When should we choose a heterologous host over the native producer for a natural product? A heterologous host like E. coli or S. cerevisiae is advantageous when the native producer is difficult to culture, has a long growth period, or is genetically intractable [10]. Key considerations include:

- Precursor Availability: Ensure the host can supply sufficient precursors or can be engineered to do so.

- Enzyme Compatibility: Verify that the host's cellular machinery (e.g., post-translational modification enzymes like PPTases for polyketide synthesis) is compatible with your pathway enzymes [10].

- Clean Background: Use engineered hosts like S. coelicolor CH999 that have native antibiotic pathways knocked out to avoid competition for building blocks [10].

Q3: How can we identify non-obvious metabolic bottlenecks that limit the yield of our target compound? Pathway-focused approaches alone are often insufficient. Systems-level strategies are required:

- Omics Integration: Combine transcriptome, metabolome, and fluxome data to get a system-wide view of metabolic limitations during different growth phases [29].

- Genome-Scale Modeling (GEM): Use GEMs to simulate metabolism and identify gene deletion or up-regulation targets that redirect flux toward your product [30] [31].

- Flux Response Analysis: Apply computational models to predict how the metabolic network responds to genetic perturbations, identifying key nodes for engineering [29].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Common Experimental Problems and Solutions

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low product titer despite high pathway expression | Metabolic burden, imbalanced flux, or insufficient precursor supply. | Implement dynamic control circuits [27], apply modular pathway engineering (MMME) [12], and enhance precursor supply via cofactor or carbon source engineering [29]. | [29] [27] [12] |

| Accumulation of toxic intermediates or byproducts | Lack of downstream enzymes or inefficient product transport. | Engineer product export systems [29], delete genes for byproduct-forming reactions [29] [10], and use biosensor-based screening to evolve strains with improved tolerance [29]. | [29] [10] |

| Poor host growth after pathway introduction | High metabolic burden or toxicity of pathway enzymes/intermediates. | Use tunable promoters to fine-tune expression [27], divide the metabolic pathway between microbial consortia [32] [27], and employ synthetic small RNAs for precise metabolic optimization [27]. | [32] [27] |

| Inconsistent performance between lab and pilot scales | Bioreactor heterogeneities (e.g., nutrient gradients). | Develop scale-down models that simulate industrial bioreactor conditions to predict and mitigate performance loss [32]. | [32] |

Detailed Protocol: Implementing a Dynamic Sensor-Regulator System

This protocol is used to address the problem of low titer due to metabolic imbalances, as listed in Table 1.

Objective: To engineer a feedback control system that dynamically regulates pathway gene expression in response to the concentration of a key intermediate metabolite.

Materials:

- Reprogrammed Transcription Factor: A transcription factor engineered to bind your target metabolite.

- Promoter Library: A set of promoters with a range of strengths responsive to the engineered transcription factor.

- CRISPRa/i System: (Optional) For applying tunable activation or repression of target genes [28].

Method:

- Biosensor Development: Identify or engineer a transcription factor whose DNA-binding activity is altered by the target intermediate metabolite [27].

- Circuit Assembly: Place the key rate-limiting genes of your biosynthetic pathway under the control of promoters recognized by the engineered transcription factor.

- Validation and Tuning:

- Transform the constructed system into your production host.

- Measure the relationship between metabolite concentration, gene expression level, and final product titer.

- Use the promoter library to fine-tune the expression dynamics until optimal productivity is achieved, preventing intermediate accumulation while maximizing flux.

Logical Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for diagnosing and resolving low product titer using dynamic regulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Systems Metabolic Engineering

| Item | Function & Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPRa/i Systems | Enables multiplexed, tunable activation (CRISPRa) or interference (CRISPRi) of target genes for metabolic flux optimization without making permanent DNA changes [28]. | Nonrepetitive extra-long sgRNA arrays for stable multi-gene repression [27]. |

| Metabolite-Responsive Biosensors | Dynamic pathway regulation; high-throughput screening of mutant libraries [29] [27]. | Lrp-based biosensor for L-valine production in C. glutamicum [29]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational platforms for predicting metabolic fluxes, identifying engineering targets, and in silico simulation of gene knockouts or additions [30] [31]. | GEMs of E. coli and S. cerevisiae for predicting targets to improve chemical production [30]. |

| Heterologous Expression Platforms | Production of natural products in genetically tractable, fast-growing hosts [10]. | E. coli for polyketides (e.g., 6-deoxyerythronolide B) [10]; Engineered Streptomyces hosts (e.g., S. coelicolor CH999) with native pathways deleted [10]. |

| Modular Cloning Toolkits | Standardized assembly of multi-gene pathways for rapid prototyping and optimization [12]. | Plug-and-play systems for Streptomyces for fine-tuning multiple targets [27]. |

| N-Nitrosodibenzylamine-d4 | N-Nitrosodibenzylamine-d4, MF:C14H14N2O, MW:230.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Inogatran | Inogatran, CAS:155415-08-0, MF:C21H38N6O4, MW:438.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Core Methodology: Multivariate Modular Metabolic Engineering (MMME)

Objective: To systematically optimize complex metabolic pathways by treating them as separate modules and balancing flux between them through multivariate experimentation.

Principle: Instead of optimizing individual genes, MMME involves dividing a metabolic pathway into distinct modules (e.g., an upstream "precursor formation module" and a downstream "product synthesis module") and simultaneously tuning the expression of all genes within each module [12].

Experimental Workflow:

- Pathway Division: Split your target biosynthetic pathway into 2-3 logical modules. For a terpenoid, this could be the MEP or MVA module (for precursor supply) and the Terpene Synthase module (for final product formation) [12].

- Module Engineering: For each module, create a library of variants with different expression levels for the constituent genes. This can be achieved using promoters of varying strengths or by modulating gene copy numbers.

- Combinatorial Testing: Construct a combinatorial library of production strains by expressing different variants of the upstream module with different variants of the downstream module.

- Screening and Analysis: Screen the combinatorial library for high producers. Analyze the performance data to identify the optimal expression balance between modules that maximizes flux to the final product while minimizing metabolic burden and intermediate accumulation.

Pathway Modularization: The diagram below illustrates the MMME workflow for engineering a generic secondary metabolic pathway.

The Metabolic Engineering Toolkit: From Gene Editing to Pathway Reconstruction

Precision Genome Editing with CRISPR/Cas9 and MAGE

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using MAGE over CRISPR/Cas9 for metabolic engineering?

MAGE (Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering) and CRISPR/Cas9 serve complementary roles. MAGE excels at introducing multiplex edits across a bacterial population simultaneously, generating vast diversity for accelerated evolution [33]. In contrast, CRISPR/Cas9 provides precise, site-specific edits and is highly effective in a wider range of organisms, including eukaryotes [34] [35]. For metabolic engineering, MAGE is powerful for optimizing multiple steps in a biosynthetic pathway at once in bacteria, while CRISPR is ideal for precise knock-outs, knock-ins, or regulatory adjustments in both native and heterologous hosts [33] [10].

Q2: How can I overcome low editing efficiency in my CRISPR experiment?

Low editing efficiency can be addressed by optimizing several factors [36] [37]:

- gRNA Design: Test 3-4 different gRNA target sequences. Ensure the gRNA is highly specific and targets a unique genomic site [36] [37].

- Delivery System: Optimize your delivery method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection, viral vectors) for your specific cell type. Using Cas9 protein with a nuclear localization signal can enhance efficiency [36].

- Component Quality and Expression: Verify the quality and concentration of your plasmid DNA, mRNA, or protein. Use a promoter that drives strong expression of Cas9 and gRNA in your host cell [36].

- Enrichment: Employ antibiotic selection or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to enrich for successfully transfected cells [37].

Q3: What strategies can minimize CRISPR/Cas9 off-target effects?

Off-target activity, where Cas9 cuts at unintended sites, is a common challenge. You can mitigate it with the following strategies [36] [37]:

- Advanced gRNA Design: Use online design tools to predict and avoid gRNAs with potential off-target sites. The 12-nucleotide "seed sequence" adjacent to the PAM should be highly specific [36] [37].

- High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Employ engineered Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) that have been designed to reduce off-target cleavage [36].

- Cas9 Nickase: Use a mutated Cas9 that makes single-strand breaks (nicks). Employing two adjacent gRNAs to create a double-strand break significantly raises specificity [37].

- Titration: Titrate the amounts of sgRNA and Cas9 to find the optimal ratio that maximizes on-target while minimizing off-target activity [37].

Q4: When should I consider a heterologous host for natural product overproduction?

A heterologous host is advantageous when the native producer is difficult to culture, has a slow growth rate, or is genetically intractable [10]. Common heterologous hosts like E. coli or engineered Streptomyces species offer fast growth, well-established genetic tools, and can be optimized for high-yield fermentation [10]. Transferring a biosynthetic pathway to a heterologous host also allows you to divorce production from the native regulatory network of the original organism, enabling greater control over the metabolic flux [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common CRISPR/Cas9 Workflow and Pain Points

The diagram below outlines a general CRISPR/Cas9 workflow, highlighting stages where common problems occur.

Troubleshooting Common CRISPR/Cas9 Issues

The table below provides specific solutions for the problems identified in the workflow above.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Editing Efficiency [36] [37] | Poor gRNA design, inefficient delivery, low expression of components, target site inaccessible. | - Design and test 3-4 different gRNAs per target [37].- Optimize delivery method for your cell type (electroporation, lipofection) [36].- Use a strong, cell-type-specific promoter [36].- Enrich for transfected cells via antibiotic selection or FACS [37]. |

| Off-Target Effects [36] [37] | gRNA has high similarity to multiple genomic sites, high concentrations of Cas9/sgRNA. | - Use bioinformatic tools to design highly specific gRNAs [36].- Utilize high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9) [36].- Deliver Cas9 as a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex for shorter activity [38].- Titrate sgRNA and Cas9 amounts to the lowest effective concentration [37]. |

| Cell Toxicity & Low Viability [36] | High levels of Cas9 nuclease activity, persistent DSB generation, delivery method. | - Optimize the concentration of delivered Cas9/gRNA; start low and titrate up [36].- Use Cas9 nickase with two gRNAs for a cleaner DSB [37].- Consider alternative, gentler delivery methods. |

| Difficulty Detecting Edits [36] | Insensitive genotyping methods, low efficiency leading to rare edits in a mixed population. | - Use sensitive detection methods like T7 endonuclease I (T7EI) assay, Surveyor assay, or tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE) [36].- Perform deep sequencing of the target locus for a comprehensive view.- Use single-cell cloning to isolate a homogeneous population [36]. |

| No PAM Sequence Near Target [37] | The target site of interest is not followed by a canonical NGG PAM sequence. | - For S. pyogenes Cas9, consider NAG as an alternative PAM, though with lower efficiency [37].- Use Cas9 orthologs or variants with different PAM requirements (e.g., Cpf1/Cas12a) [38]. |

| Ac-YVAD-AOM | Ac-YVAD-AOM, CAS:154674-81-4, MF:C33H42N4O10, MW:654.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methenamine Hippurate | Methenamine Hippurate |

Troubleshooting MAGE for Metabolic Engineering

Problem: Low Crossover Efficiency or Poor Diversity MAGE relies on high-efficiency incorporation of oligonucleotides into the genome of replicating cells.

- Causes: Low efficiency of the recombinase system (e.g., Lambda Red), oligonucleotide degradation, or cells not being in an active state of replication.

- Solutions: [33]

- Ensure the bacterial strain expresses the Lambda Red recombination system at high levels.

- Design oligonucleotides with protective phosphorothioate linkages at the ends to resist nuclease degradation.

- Time the delivery of oligonucleotides to coincide with the peak of DNA replication in a large cell population.

- Perform multiple cycles of MAGE to allow mutations to accumulate and combine.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout in Fungi/Shiitake Mushroom

This protocol, adapted from a study in Lentinula edodes, provides a framework for implementing CRISPR in non-model fungi, which is highly relevant for engineering natural product producers [35].

1. Design and Cloning of gRNA:

- Identify an Endogenous U6 Promoter: Search the genome of your target fungus for a U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) gene and use the ~500 bp sequence upstream as the promoter for gRNA expression [35].

- Select a Strong Constitutive Promoter: Use a promoter like gpd (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) to drive expression of the Cas9 protein [35].

- gRNA Design: Design 20-nt gRNA sequences targeting the first two-thirds of the coding sequence of your gene of interest. Ensure the target is followed by an NGG PAM [35].

- Cloning: Clone the U6 promoter and gRNA scaffold into a binary vector. Then, clone the gpd-Cas9 expression cassette into the same vector. Finally, insert the annealed oligos corresponding to your gRNA target sequence into the AarI site of the vector [35].

2. Fungal Transformation via Protoplasts:

- Protoplast Isolation: Culture mycelia in liquid medium for 10 days. Harvest and digest the cell wall using a 2.5% Lysing Enzyme solution to isolate protoplasts [35].

- Transformation: Suspend 10^6 protoplasts in 0.6 M sucrose and incubate with 20 µg of plasmid DNA on ice. Add polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution to facilitate DNA uptake, then plate the transformed protoplasts on regeneration media containing a selective antibiotic (e.g., hygromycin B) [35].

3. Screening and Validation:

- After 3-4 weeks, isolate transformed mycelia and culture them separately [35].

- Extract genomic DNA and perform PCR amplification of the target locus.

- Analyze mutations by Sanger sequencing of the PCR products. The error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathway will result in insertion/deletion (indel) mutations at the target site [35].

Workflow: Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE)

The MAGE cycle allows for rapid, continuous diversification of a microbial population, ideal for optimizing metabolic pathways [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines key reagents and their functions for setting up precision genome editing experiments.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants [36] | Engineered Cas9 proteins with reduced off-target effects while maintaining high on-target activity. | Essential for experiments requiring high specificity, such as modeling specific disease mutations in metabolic pathways. |

| Cas9 Nickase [34] [37] | A mutated Cas9 that cuts only one DNA strand, reducing off-target activity. | Requires two adjacent gRNAs to create a double-strand break, thereby increasing specificity. Useful for HDR experiments. |

| Base Editors [34] | Fusion of catalytically impaired Cas9 (dCas9 or nCas9) with a deaminase enzyme. Enables direct, template-free conversion of one base pair to another without causing a DSB. | Ideal for introducing precise point mutations to study or improve enzyme function in a biosynthetic pathway. Has a specific editing window. |

| Prime Editors [34] | Fusion of Cas9 nickase with a reverse transcriptase. Uses a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) to directly write new genetic information into a target DNA site. | Can mediate all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without a donor template. |

| Endogenous U6 Promoter [35] | A snRNA promoter native to your host organism used to drive the expression of gRNAs. | Critical for efficient gRNA expression in non-model organisms like fungi. Using a heterologous promoter may not work. |

| Lambda Red Recombinase System [33] | A bacteriophage-derived system that promotes homologous recombination in E. coli and other bacteria. | The core engine of MAGE, enabling the incorporation of synthetic single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligonucleotides into the bacterial genome. |

| ssDNA Oligonucleotides (for MAGE) [33] | Short, single-stranded DNA molecules (~90 bases) designed to introduce specific mutations into the genome. | Must be designed with homology arms complementary to the lagging strand of DNA replication. Phosphorothioate modifications can improve stability. |

| Leelamine Hydrochloride | Leelamine Hydrochloride, CAS:16496-99-4, MF:C20H32ClN, MW:321.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Beloxepin | Beloxepin, CAS:150146-06-8, MF:C19H21NO2, MW:295.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Heterologous Pathway Reconstruction and Assembly in Chassis Strains

In the field of metabolic engineering for the overproduction of natural products, heterologous pathway reconstruction has emerged as a powerful strategy. This approach involves transferring biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) from native producers into well-characterized chassis strains to overcome challenges such as poor cultivability, low product yields, or complex genetic backgrounds in the original organisms [10] [39]. For researchers and drug development professionals, establishing efficient heterologous expression systems is crucial for accessing the vast potential of natural products, particularly from challenging sources like marine microorganisms where over 99% remain unexplored [39]. This technical support center provides practical guidance for troubleshooting common issues encountered during these complex experiments.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Host Selection and Engineering

Question: What are the key considerations when selecting a chassis strain for heterologous expression of bacterial natural product pathways?

The choice of heterologous host depends on multiple factors including the source of the pathway, required precursors, and genetic compatibility. For actinomycetes-derived pathways, Streptomyces lividans and Streptomyces coelicolor are common choices, particularly engineered variants like S. coelicolor CH999 that have native antibiotic pathways knocked out to reduce metabolic competition [10]. Escherichia coli offers advantages of rapid growth and well-established genetic tools but may require extensive engineering to provide necessary precursors and cofactors [10]. For example, successful heterologous production of the polyketide 6-deoxyerythronolide B (6dEB) in E. coli required introduction of the sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase gene and S. coelicolor genes pccA and B to enable (2S)-methylmalonyl-CoA biosynthesis [10].

Question: How can we engineer precursor supply in heterologous hosts?

Key strategies include:

- Introducing heterologous enzymes: As demonstrated in the E. coli erythromycin system, introducing propionyl-CoA ligase and biotin ligase enhanced precursor supply [10]

- Knocking out competing pathways: Eliminating propionate catabolism in E. coli redirected flux toward polyketide precursors [10]

- Utilizing metabolic modeling tools: Computational approaches like UP Finder can identify optimal gene overexpression targets to enhance precursor supply [40]

Pathway Assembly and Expression

Question: What molecular steps are involved in reconstructing complete biosynthetic pathways in heterologous hosts?

A systematic, stepwise approach is recommended, as demonstrated in the reconstruction of fungal terreic acid biosynthesis in Pichia pastoris [41]. The process involves:

- Gene identification and validation: Correctly identifying protein-coding sequences and intron boundaries through cDNA sequencing

- Pathway activation: Co-expressing phosphopantetheinyl transferases (e.g., npgA) to activate polyketide synthases

- Stepwise assembly: Introducing individual pathway genes sequentially to verify function and isolate intermediates [41]

For the terreic acid pathway, this approach revealed that cytochrome P450 monooxygenase AtE hydroxylates 3-methylcatechol to produce 3-methyl-1,2,4-benzenetriol, with assistance from a smaller cytochrome P450 monooxygenase AtG—functions that were previously uncharacterized in the native host [41].

Question: How can we activate silent or poorly expressed biosynthetic gene clusters in heterologous systems?

Several strategies have proven effective:

- Promoter engineering: Using strong, constitutive promoters to drive expression of pathway genes [39]

- Regulatory element manipulation: Expressing pathway-specific activators or deleting repressor genes [39]

- Chassis optimization: Selecting hosts phylogenetically close to the native producer for better compatibility of transcriptional machinery [39]

- Metabolic balancing: Fine-tuning expression of individual pathway enzymes to avoid bottlenecks and toxic intermediate accumulation [10]

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Selected Heterologous Expression Systems

| Product | Native Host | Heterologous Host | Key Genetic Modifications | Titer Achieved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-deoxyerythronolide B | Saccharopolyspora erythraea | Escherichia coli | Introduction of sfp PPTase; pccA/B genes for methylmalonyl-CoA; propionate catabolism knockout | 0.1 mmol/g cellular protein/day | [10] |

| 6-methylsalicylic acid | Aspergillus terreus | Pichia pastoris | Co-expression of npgA (PPTase) with atX (PKS) | 2.2 g/L | [41] [42] |

| 3-methylcatechol | Aspergillus terreus | Pichia pastoris | Expression of atA (decarboxylase) in 6-MSA producing strain | 61.0 mg/L | [41] |

| Daptomycin | Streptomyces roseosporus | Streptomyces lividans | Elimination of native actinorhodin pathway | Increased yield and purity | [10] |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Heterologous Hosts for Natural Product Production

| Host Organism | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Rapid growth; Extensive genetic tools; High transformation efficiency | Limited native precursor supply; May lack necessary post-translational modifications | Type I PKS; NRPS; Hybrid systems [10] |

| Streptomyces spp. | Endemic antibiotic production machinery; Native precursor supply | Slower growth; More complex genetics | Actinomycetes-derived pathways; Complex polyketides [10] |

| Pichia pastoris | Eukaryotic protein processing; High-density cultivation | Limited genetic tools; May not process bacterial pathways efficiently | Fungal pathways; Eukaryotic natural products [41] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Stepwise Pathway Assembly in Yeast

Based on the successful reconstruction of terreic acid biosynthesis in Pichia pastoris [41]:

Gene Isolation and Preparation

- Isolate mRNA from native producer (Aspergillus terreus)

- Perform reverse transcription to cDNA

- Sequence to identify intron-exon boundaries and correct coding sequences

- Clone intron-free versions into P. pastoris expression vectors

Strain Construction

- Start with base strain expressing necessary auxiliary enzymes (e.g., npgA for PPTase activity)

- Transform with polyketide synthase gene (atX) and confirm 6-MSA production

- Introduce decarboxylase (atA) and verify 3-methylcatechol production

- Add cytochrome P450 genes (atE, atG) stepwise, confirming new intermediate formation at each step

- Complete pathway with oxidoreductase (atC) to achieve final product

Analysis and Optimization

- Extract metabolites at each stage using appropriate solvents

- Analyze by HPLC and LC-MS to identify intermediates and final products

- Measure titers and identify potential bottlenecks

- Optimize promoter strength and culture conditions for balanced expression

Protocol 2: Heterologous Expression of Bacterial Pathways in E. coli

Adapted from successful expression of erythromycin PKS in E. coli [10]:

Host Engineering

- Introduce phosphopantetheinyl transferase gene (e.g., sfp) for ACP activation

- Provide pathways for necessary extender units (e.g., methylmalonyl-CoA)

- Knock out competing metabolic pathways

- Overexpress precursor supply enzymes

Pathway Assembly

- Clone large PKS/NRPS genes using appropriate vectors (BACs, cosmids)

- Consider splitting very large systems across multiple plasmids with compatible replicons

- Test individual module function where possible

Fermentation Optimization

- Develop fed-batch strategies to maintain precursor supply

- Optimize induction timing and temperature

- Implement extraction methods for intracellular products

Pathway Visualization

Heterologous Pathway Assembly Workflow

Terreic Acid Biosynthesis Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Heterologous Pathway Reconstruction

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chassis Strains | E. coli BL21(DE3), S. lividans TK24, P. pastoris GS115 | Provide clean metabolic background for pathway expression | Select based on phylogenetic proximity to native producer [10] [39] |

| Vector Systems | BACs, Cosmids, Integrative plasmids | Carry large BGCs; Enable stable maintenance | Ensure compatibility with host and pathway size [39] |

| Enzyme Activation | Phosphopantetheinyl transferases (Sfp, NpgA) | Activate ACP domains in PKS and NRPS systems | Essential for polyketide and nonribosomal peptide production [10] [41] |

| Precursor Supply | Propionyl-CoA ligase, Biotin ligase, Methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase | Provide essential building blocks | Critical for heterologous hosts lacking native precursor pathways [10] |

| Metabolic Tools | UP Finder modeling software, antiSMASH | Identify overexpression targets; Predict BGC function | Computational guidance for metabolic engineering [40] |

| Culture Additives | Biosynthetic precursors, Cofactor supplements | Enhance pathway flux and product yield | Optimize based on specific pathway requirements [10] |

Core Concepts: Multi-Omics Integration in Metabolic Engineering

What is the fundamental principle behind using multi-omics data to understand metabolic regulation? Metabolism is regulated by a complex interplay of different layers of control. The maximal theoretical flux through an enzyme-catalyzed reaction is set by the enzyme's abundance (a function of gene expression), while the actual instantaneous flux is controlled metabolically through interactions with substrates, products, and allosteric effectors [43]. Therefore, no single omics data type can fully characterize the metabolic state. Integrating genomics, transcriptomics, and fluxomics provides a holistic view, disassembling the interdependence between these regulatory layers to accurately characterize the metabolic landscape and identify true engineering targets [43] [44].

How do the different omics layers interact within the central dogma? The flow of information generally progresses from DNA to RNA to protein to metabolites and finally to metabolic fluxes. However, the relationships are not simple one-to-one correlations [45]. High transcript levels do not always result in proportionately high protein levels due to post-transcriptional regulation and protein turnover. Similarly, high enzyme abundance does not guarantee high metabolic flux if the enzyme is allosterically inhibited or substrate-limited [43] [46]. Fluxomics, which measures the actual rates of metabolic reactions, serves as the ultimate readout of cellular physiology, integrating the effects of all underlying regulatory mechanisms [44].

The diagram below illustrates the typical workflow for integrating multi-omics data to understand and engineer metabolism, from data generation to model-informed intervention.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: We see discrepancies between our transcriptomics, proteomics, and fluxomics data. For instance, a gene is highly upregulated, but the corresponding metabolic flux decreases. How should we resolve this?

This is a common scenario indicating effective metabolic regulation.

- Potential Cause 1: Metabolic (Allosteric) Control. The enzyme catalyzing the reaction may be inhibited by the accumulation of a downstream metabolite or a cofactor. The flux is controlled metabolically, not by enzyme abundance. The overexpressed enzyme is essentially idle [43] [46].

- Potential Cause 2: Substrate Limitation. The reaction's substrate may not be available in sufficient concentration, creating a bottleneck upstream. The increased enzyme level cannot overcome the lack of substrate [43].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Check Metabolomics Data: Analyze intracellular metabolite levels. Look for accumulation of the reaction's substrate (suggesting enzyme inhibition) or depletion (suggesting a downstream bottleneck) [43].

- Investigate Allosteric Regulators: Consult biochemical databases (e.g., BRENDA) to identify known allosteric activators or inhibitors of the enzyme and check their levels in your metabolomics data [43].

- Use a Model-Based Approach: Implement pipelines like INTEGRATE, which uses constraint-based models to intersect transcriptomic and metabolomic data to discriminate between reactions controlled at the gene expression level versus the metabolic level [43].