Overcoming Technical Barriers in Natural Product Drug Discovery: Modern Strategies for Screening and Characterization

This article addresses the persistent technical challenges in natural product (NP)-based drug discovery, a field responsible for over 50% of approved therapeutics.

Overcoming Technical Barriers in Natural Product Drug Discovery: Modern Strategies for Screening and Characterization

Abstract

This article addresses the persistent technical challenges in natural product (NP)-based drug discovery, a field responsible for over 50% of approved therapeutics. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the revival of NP research driven by advanced analytical tools, genome mining, and improved microbial culturing. We provide a comprehensive guide spanning from foundational principles and modern methodological applications—including HPLC-MS/MS, HTS, and bioaffinity strategies—to practical troubleshooting and assay optimization. The content also covers validation frameworks and comparative analyses of NP versus synthetic libraries, offering a holistic perspective for integrating NPs into contemporary drug discovery pipelines to combat pressing issues like antimicrobial resistance.

The Resurgence of Natural Products: Confronting Historical Hurdles in Modern Drug Discovery

The Historical Significance and Modern Relevance of Natural Products

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Bioassay Interference in Natural Product Screening

Problem: High false-positive or irreproducible results in bioassays when testing complex natural product extracts.

Why this happens: Natural product extracts are complex mixtures that can contain compounds which non-specifically interfere with assay systems through mechanisms like protein precipitation, oxidation, or fluorescence quenching [1].

Solution:

- Include appropriate controls: Test for non-specific inhibition using denatured enzyme controls or add detergent to identify promiscuous inhibitors [1]

- Use counter-screening assays: Implement orthogonal assays with different detection mechanisms to confirm specific activity [1]

- Apply dose-response testing: True bioactive compounds typically show stoichiometric dose-response curves rather than all-or-nothing effects [1]

- Implement rapid fractionation: If interference is suspected, perform initial fractionation and retest to determine if activity tracks with specific fractions [2]

Prevention: Standardize extraction methods and include assay interference panels during initial screening phases [1].

Table: Common Natural Product Assay Interferences and Solutions

| Interference Type | Detection Method | Solution Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Protein precipitation | Turbidity measurement | Centrifugation/filtration prior to detection |

| Fluorescence quenching | Fluorescence controls | Use non-fluorescence based confirmatory assays |

| Redox activity | Redox-sensitive dyes | Include reducing agents or redox controls |

| Non-specific binding | Detergent sensitivity | Add mild detergents to assay buffer |

Guide 2: Managing Variability in Botanical Natural Products

Problem: Inconsistent experimental results due to variability in botanical natural product composition.

Why this happens: Botanical composition varies due to genetic differences, growing conditions, harvest time, post-harvest processing, and extraction methods [2].

Solution:

- Authentication: Verify species identity through taxonomic experts and voucher specimens deposited in herbariums [2]

- Standardization: Develop chemical fingerprints using HPLC-MS or NMR and quantify marker compounds [2]

- Batch documentation: Maintain detailed records for each batch including source, processing method, and storage conditions [2]

- Stability testing: Conduct accelerated stability studies to establish shelf life and proper storage conditions [2]

Prevention: Source material from controlled cultivation when possible and obtain sufficient material for entire study at outset [2].

Guide 3: Translating In Vitro Natural Product Activity to In Vivo Efficacy

Problem: Promising in vitro activity does not translate to in vivo models.

Why this happens: Poor bioavailability, rapid metabolism, or insufficient tissue exposure due to unfavorable pharmacokinetic properties [3] [4].

Solution:

- Early ADME screening: Implement absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profiling early in discovery cascade [3]

- Plasma protein binding: Determine extent of protein binding as it affects free drug concentration [3]

- Metabolite identification: Identify major metabolites and test their activity [2]

- Formulation optimization: Improve bioavailability through formulation approaches like lipid-based delivery systems [5]

Prevention: Incorporate property-based design alongside potency optimization and use computational tools to predict pharmacokinetic properties [4].

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What potency threshold should be used to prioritize natural product hits for further investigation?

For antimicrobial screening, extracts with LC50 ≤ 100 ppm are considered good starting points, while pure compounds with LC50 ≤ 10 ppm are promising candidates for prototype development [6]. However, potency should be considered alongside other factors like selectivity, structural novelty, and feasibility of synthesis or sustainable sourcing [6].

FAQ 2: What level of characterization is required for botanical natural products before initiating research studies?

Botanical natural products used in research should be [2]:

- Representative of what consumers actually use

- Authenticated to species level with voucher specimens

- Characterized for active or marker compounds

- Tested for contaminants and adulterants

- Available in sufficient quantity for entire study

- Demonstrated to have batch-to-batch consistency

FAQ 3: How can researchers overcome the structural complexity challenges in natural product synthesis?

Strategic approaches include [5]:

- Utilizing synthetic biology to engineer organisms for production

- Applying click chemistry for modular assembly

- Implementing AI-based retrosynthetic analysis

- Forming partnerships with specialized CDMOs with natural product expertise

- Using CRISPR-based genome editing to enhance yields in native producers

FAQ 4: What alternative models are available when animal models fail to predict human efficacy?

Emerging alternatives to traditional animal models include [4]:

- Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that can be differentiated into human disease-relevant cell types

- Organ-on-a-chip systems that better recapitulate human physiology

- 3D organoid cultures that exhibit more complex tissue organization

- In silico models and AI-based prediction platforms

- Human biomarker-driven proof-of-concept trials

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Approach for Characterizing Botanical Natural Products

Purpose: To ensure consistent, well-characterized botanical natural products for research studies [2].

Materials:

- Authentication: Taxonomic experts, DNA barcoding kits, herbarium supplies

- Chemical characterization: HPLC-MS system, NMR spectrometer, reference standards

- Contaminant testing: Microbial culture media, heavy metal analysis kits, pesticide screening columns

Procedure:

- Source authentication: Obtain from reputable supplier with taxonomic verification. Deposit voucher specimen in herbarium [2]

- Extraction preparation: Use standardized extraction protocol (specify solvent, temperature, time, ratio)

- Chemical profiling:

- Perform untargeted metabolomics via HPLC-HRMS

- Quantify known active constituents or marker compounds

- Establish chemical fingerprint with acceptance criteria [2]

- Contaminant screening:

- Test for heavy metals (arsenic, cadmium, lead, mercury)

- Screen for pesticide residues

- Conduct microbial load testing (total aerobic count, yeast/mold)

- Check for aflatoxins and mycotoxins [2]

- Stability assessment:

- Conduct accelerated stability studies (e.g., 40°C/75% RH for 3 months)

- Monitor chemical profile and biological activity over time [2]

Protocol 2: Implementation of a Tiered Natural Product Screening Cascade

Purpose: To efficiently identify and validate true bioactive natural products while minimizing false positives [1].

Materials:

- Primary screening: High-throughput screening capability, robotic liquid handlers

- Counter-screen assays: Orthogonal assay formats, interference detection reagents

- Secondary assays: Disease-relevant cellular models, mechanism-of-action tools

Procedure:

- Primary screening:

- Test at single concentration (e.g., 10-100 μg/mL for extracts, 1-10 μM for pure compounds)

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle, positive control, interference controls) [1]

- Interference testing:

- Test for assay interference (aggregation, fluorescence, reactivity)

- Include detergent-based or enzyme-denaturation controls [1]

- Potency determination:

- Conduct dose-response with minimum of 5 concentrations

- Calculate IC50, EC50, or LC50 values [6]

- Specificity assessment:

- Test against related targets/cell lines to determine selectivity

- Perform cytotoxicity counter-screening [1]

- Mechanistic studies:

- Investigate time-dependence, reversibility

- Conduct target engagement and pathway modulation studies

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized plant extracts | Provides consistent starting material for biological testing | Ensure proper authentication and chemical characterization [2] |

| Analytical standards | Enables compound identification and quantification | Include both marker compounds and suspected actives [2] |

| Bioassay kits | Measures biological activity | Optimize for natural product compatibility [1] |

| Fraction libraries | Facilitates activity-guided fractionation | Generate using orthogonal separation methods [2] |

| Metabolomics kits | Provides comprehensive chemical profiling | Use both LC-MS and NMR-based approaches [2] |

| ADIME screening tools | Predicts in vivo pharmacokinetics | Include metabolic stability, permeability assays [3] |

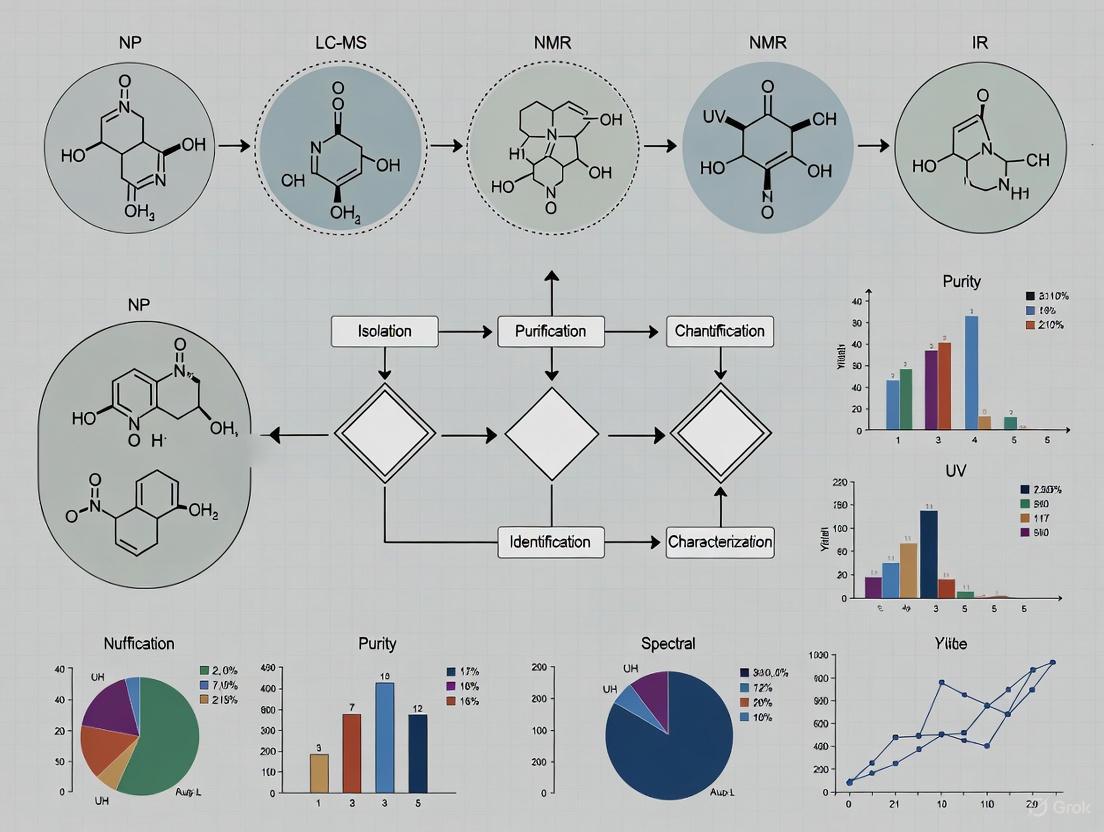

Workflow Visualizations

Natural Product Characterization Workflow

(Natural Product Characterization Workflow: A sequential process from source material to characterized research material)

Natural Product Lead Prioritization Framework

(Natural Product Lead Prioritization: Multi-tiered screening cascade with feedback loops)

Integrated Drug Discovery Pathway

(Integrated Drug Discovery Pathway: Conventional process with natural product integration points and challenges)

Natural products (NPs) are a cornerstone of drug discovery, distinguished by their unparalleled structural diversity and broad-spectrum bioactivity honed by millions of years of evolutionary refinement [7]. However, the path from crude extract to characterized bioactive compound is fraught with technical challenges. The core of this difficulty lies in the analytical process itself: researchers must navigate a labyrinth of complexity, from the initial screening of intricate biological mixtures to the final definitive structural characterization. This technical support center is designed to function as a strategic guide, directly addressing the specific, high-impact problems encountered in daily laboratory work. By providing clear, actionable troubleshooting protocols and foundational knowledge, we aim to empower researchers to overcome these barriers, enhance the reliability of their data, and accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic agents.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section provides targeted solutions for common, yet critical, technical challenges in natural product analysis using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My LC-MS analysis shows inconsistent results and high background noise. What are the most likely sources of contamination? Systematic errors and artefacts are common in trace-level HPLC-MS analysis, and the mass spectrometer is the source of problems in only a minority of cases [8]. The most frequent culprits are:

- Solvents and Reagents: HPLC-grade solvents are often tested for UV transparency but not for a low MS background. Contaminants in water or organic solvents can produce a high chemical background [8].

- Sample Preparation: The sample matrix itself can introduce ions that suppress the ionization of your target analytes [8].

- HPLC System: The stationary phases in reversed-phase HPLC columns can slowly hydrolyze, releasing bound lipophilic rests that increase the background. Active sites on the phase can also cause adsorption and degradation of compounds at trace levels [8].

- Buffer Salts: Non-volatile buffers (e.g., phosphate buffers) are incompatible with MS and create severe contamination and ion suppression [8].

Q2: Why is the signal for my target compound so weak, even though I know it's present in the sample? Signal weakness or loss is often related to compound ionization or system configuration:

- Ion Suppression: Your analyte's ionization can be suppressed by a more easily ionizable background or by a co-eluting substance. This is a particularly common issue with Electrospray Ionization (ESI) [8].

- Adduct Formation: Ion-molecule adducts can form between analytes and alkaline metal ions (e.g., Na+, K+) or ammonium, which may disperse the signal for a single compound across multiple m/z values [8].

- Source Misalignment: In Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), a misaligned corona discharge needle can cause highly reproducible non-linearity in calibration curves, affecting sensitivity [8].

- In-Source Fragmentation: The compound might be fragmenting before it reaches the mass analyzer, making the molecular ion difficult to detect [9].

Q3: I have an accurate molecular mass, but I'm finding multiple structural matches in databases. How can I confidently identify the correct one? This is a fundamental challenge in natural products research. An accurate mass alone is often insufficient because many isomeric molecules share the same molecular formula [9]. To assign the correct structure, you need orthogonal information:

- Tandem MS (MS/MS): Use MS/MS to generate a fragmentation fingerprint. The fragmentation pattern can be compared to a standard run on the same instrument under identical conditions [9].

- Chromatographic Retention Time: Matching the retention time to an authentic standard provides strong evidence [9].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): NMR remains the gold standard for de novo structure elucidation, especially for distinguishing between isomers and determining stereochemistry [9].

Advanced Troubleshooting Guide

For persistent or complex issues, follow this structured diagnostic approach.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common LC-MS Performance Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Background Noise | Contaminated mobile phase or sample [8] | Run a blank gradient with no injection. | Use MS-grade solvents and additives. Re-prepare mobile phases. Purify sample if needed. |

| Column bleed (hydrolysis of stationary phase) [8] | Check if noise increases with column temperature/age. | Replace column. Use a guard column. | |

| Poor Sensitivity | Ion suppression from co-eluting compounds [8] | Post-infuse analyte and inject sample to observe signal dip. | Improve chromatographic separation. Dilute sample. Modify extraction/cleanup. |

| Source contamination or misalignment [8] | Check instrument calibration and tuning reports. | Clean ion source. Perform mass calibration and instrument tuning. | |

| Irreproducible Quantification | Non-linear calibration due to source issues [8] | Inspect calibration curve for consistent non-linearity. | Verify and realign the corona needle (APCI). Check for active sites in flow path. |

| Adsorption to active sites in flow path or column [8] | Analyze a standard at high and low concentration; look for signal loss. | Use inert (e.g., PEEK) components. Passivate system. Add modifier to mobile phase. | |

| Inability to Identify Unknown | Lack of orthogonal data for isobaric compounds [9] | Search molecular formula in Dictionary of Natural Products; note number of hits. | Acquire MS/MS spectra. Use orthogonal separation (HILIC, etc.). Isolate compound for NMR analysis. |

Protocol: Systematic LC-MS Performance Diagnosis

Isolate the Subsystem: Begin by determining whether the problem originates from the LC system, the MS, or the sample itself.

- Step 1: Inject a pure standard with a known calibration. If the signal is normal, the problem is likely sample-specific (e.g., matrix effects). If the signal is abnormal, proceed to Step 2.

- Step 2: Run a system suitability test with a standard mix. Evaluate pressure, peak shape, and retention time consistency to diagnose LC issues.

- Step 3: Run a solvent blank. A high background indicates contaminated mobile phases or a dirty source.

Check Instrument Calibration: Regularly verify mass accuracy and sensitivity using manufacturer-recommended calibration mixes. Poor sensitivity or mass accuracy in the calibration process directly points to an MS source or analyzer problem [10].

Validate Sample Introduction: Ensure the autosampler is functioning correctly by checking for precise injection volumes and the absence of carryover, which can be a significant source of contamination and inaccurate quantification [11].

The following workflow diagrams the logical process for moving from problem observation to resolution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The selection of reagents and consumables is a critical, yet often overlooked, factor in determining the success of a natural products analysis project. The following table details key materials and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product LC-MS

| Item | Function & Importance | Technical Notes & Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| MS-Grade Solvents | Provide a low chemical background for high-sensitivity detection. Using HPLC-grade solvents tested only for UV can introduce significant noise [8]. | Always use solvents and water specifically certified for LC-MS to minimize baseline artefacts and ion suppression. |

| Volatile Buffers & Additives | Enable efficient desolvation and ionization in the MS source. Non-volatile buffers (e.g., phosphates) are incompatible and will contaminate the instrument [8]. | Use ammonium formate/acetate, formic acid, or acetic acid. Avoid halides and phosphates. |

| Biocompatible LC Systems | Prevent adsorption of analytes to active metal surfaces in the flow path, which is crucial for recovering certain natural products at trace levels. | For sensitive compounds, use systems with PEEK, MP35N, gold, or ceramic flow paths [12]. |

| U/HPLC Columns with High Efficiency | Provide the chromatographic resolution needed to separate complex natural product extracts, reducing ion suppression and enabling accurate identification [13]. | Select columns with small particle sizes (e.g., sub-2µm) and appropriate stationary phases (C18, HILIC, etc.) for your compound class. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Account for matrix-induced ion suppression/enhancement and correct for analyte loss during sample preparation, ensuring accurate quantification [13]. | Ideally, use a (^{13}\text{C}) or (^{15}\text{N})-labeled version of the analyte. If unavailable, use a closely related structural analogue. |

Experimental Workflows: From Screening to Confirmation

A robust analytical workflow is essential for navigating the complexity of natural product extracts. The process typically moves from untargeted screening to targeted characterization.

Core Protocol: Untargeted Screening for Novel Natural Products

Principle: This methodology uses high-resolution LC-MS to comprehensively profile a complex natural product extract without prior knowledge of its composition, aiming to highlight novel or unknown compounds for further investigation [9] [13].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Minimally, a crude extract is dissolved in an MS-compatible solvent and centrifuged or filtered to remove particulate matter. The goal is to avoid introducing unnecessary complexity or contaminants [8].

- Chromatographic Separation: Use a UHPLC system with a binary pump and a high-efficiency reversed-phase column (e.g., C18, 1.7-1.8µm particle size). Employ a long, shallow gradient (e.g., 5-95% organic modifier over 30-60 minutes) to maximize separation of the complex mixture [12] [13].

- High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Instrument: A Q-TOF or Orbitrap mass spectrometer is preferred for its high mass accuracy and resolution [12] [13].

- Acquisition: Data is collected in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. The instrument continuously performs full MS scans (e.g., m/z 50-1500) and automatically selects the most intense ions from each scan for MS/MS fragmentation.

- Data Processing and Dereplication:

- Molecular Formula Assignment: Use software to deconvolute the data, assigning molecular formulas based on accurate mass and isotope patterns [9].

- Database Search: Search the assigned formulas against natural product databases (e.g., Dictionary of Natural Products, AntiMarin, COCONUT, LANaPDB). This critical "dereplication" step identifies known compounds, saving effort on re-isolation [9] [14].

- Novelty Assessment: Compounds whose formulas do not return a database match become high-priority targets for isolation and full structure elucidation.

The following diagram illustrates this multi-stage workflow.

Core Protocol: Structural Confirmation Using LC-MS/MS and NMR

Principle: Once a compound of interest is isolated, its structure must be confirmed. This protocol leverages the complementary strengths of MS/MS and NMR to achieve definitive identification [9].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- LC-MS/MS Analysis of Pure Compound:

- Inject the purified compound.

- Acquire high-quality MS/MS spectra at multiple collision energies to generate a comprehensive fragmentation pattern.

- Interpret the fragments to propose a substructure or to match against a spectral library if available [9].

- NMR Spectroscopy:

- Prepare a purified sample (micrograms to milligrams, depending on sensitivity).

- Acquire a suite of 1D and 2D NMR experiments (e.g., (^{1}\text{H}), (^{13}\text{C}), COSY, HSQC, HMBC).

- NMR data provides definitive proof of constitution, connectivity, and stereochemistry, which MS cannot reliably achieve on its own [9].

- Data Integration:

- Correlate the MS/MS fragmentation pathways with the structural features elucidated by NMR.

- This combined approach provides a high degree of confidence in the final structural assignment.

Navigating the technical journey from screening to characterization in natural products research demands a systematic approach to troubleshooting and a deep understanding of the strengths and limitations of analytical technologies like LC-MS and NMR. By recognizing common pitfalls such as contamination, ion suppression, and the challenges of dereplication, and by implementing the detailed protocols and diagnostic guides provided herein, researchers can transform frustration into discovery. This technical support framework empowers scientists to generate more reliable and reproducible data, ultimately streamlining the path to uncovering the next generation of natural product-based therapeutics.

In the field of natural product (NP) drug discovery, a significant and persistent perception gap exists between industry and academic stakeholders regarding research strategies and their effectiveness. While natural products have undisputedly played a leading role in developing novel medicines, trends in pharmaceutical research investments indicate that NP research is neither prioritized nor perceived as fruitful in drug discovery programmes compared with incremental structural modifications and large-volume high-throughput screening (HTS) of synthetic compounds [15] [16].

This gap demonstrates a fundamental dissonance: individuals from both sectors perceive high potential in NPs as drug leads, yet simultaneously express criticism toward prevalent industry-wide discovery strategies [15]. This article explores the technical barriers underpinning this divide and provides practical troubleshooting guidance to enhance collaborative research efficacy, bridging the gap between theoretical academic research and industry's practical application needs.

Survey Insights: Quantifying the Divide

Stakeholder surveys reveal critical differences in how industry and academic professionals perceive drug discovery strategies and outcomes. A comprehensive survey of 52 industry and academic experts provides quantitative evidence of this divide [15] [16].

Table 1: Perceived Effectiveness of Drug Discovery Strategies

| Discovery Strategy | Industry Perception | Academic Perception | Effectiveness Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Products | Lower priority despite high potential | High potential, undervalued | Significant |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) of Synthetics | Higher hit rates perceived | Lower hit rates perceived | Moderate |

| Incremental Structural Modifications | Prioritized in R&D investments | Less favored compared to NPs | Significant |

Table 2: Stakeholder Satisfaction with Current Strategies

| Assessment Area | Industry Satisfaction | Academic Satisfaction | Shared Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Discovery Efforts | Not more effective than previous decades | Not more effective than previous decades | Perception of stalled progress |

| Company/Industry Strategy | Highly critical | Critical | Widespread dissatisfaction |

| Hit Rates in HTS | Higher perception | Lower perception | Methodological differences |

Survey findings indicate that industry contacts perceived higher hit rates in HTS efforts compared to academic respondents, despite neither group perceiving current discovery efforts as more effective than previous decades [16]. Surprisingly, many industry contacts expressed strong criticism toward prevalent company and industry-wide drug discovery strategies, indicating a high level of dissatisfaction within the commercial sector [15].

Technical Barriers in Natural Product Research

Characterization and Reproducibility Challenges

Botanical natural products present unique technical hurdles that contribute to the industry-academia divide. These complex mixtures differ from pharmaceutical drugs in that their composition varies depending on genetics, cultivation conditions, and processing methods [17]. This inherent variability creates significant reproducibility challenges, as many studies are conducted with poorly characterized materials, making results difficult to interpret or replicate [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Characterization Challenges

Q: How can I ensure my botanical natural product is suitable for research?

- A: The ideal botanical natural product for research should be: representative of what consumers use; authenticated (species verified); well-characterized with known active constituents; free of contamination and adulteration; available in sufficient quantity; and consistent across the study duration with established shelf life and batch-to-batch reproducibility [17].

Q: What are the essential steps for characterizing a botanical study material?

- A: Follow this workflow: (1) Conduct thorough literature research on major metabolites and traditional use; (2) Select and authenticate botanical material using voucher specimens; (3) Characterize chemically using targeted or untargeted methods; (4) Ensure stability and batch-to-batch consistency [17].

Q: Why is a voucher specimen necessary?

- A: A voucher specimen provides a permanent, verifiable record of the plant material used in your research. It allows for taxonomic identification by a trained botanist and is essential for preserving a record of the original sample, enabling future replication studies. Major natural product journals require deposition in a herbarium [17].

Technological and Strategic Hurdles

The pharmaceutical industry's shift away from NP research stems from several perceived barriers: traditional NP screening is labor-intensive, requiring multi-step extractions and structural elucidation; production scaling of rare metabolites presents bottlenecks; and legal complexities surrounding international collaboration under frameworks like the Nagoya Protocol create additional hurdles [7]. Furthermore, the "one-drug-one-target" paradigm that dominates pharmaceutical development conflicts with the inherent multi-target nature of many natural products [18].

Bridging the Gap: Modern Methodologies and Solutions

Advanced Characterization Workflows

Implementing robust, standardized workflows for natural product characterization is fundamental to bridging the perception gap. The following methodology ensures research materials meet rigorous standards for reproducible science.

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive Botanical Natural Product Characterization

Objective: To authenticate, characterize, and ensure quality consistency of botanical natural products for research applications.

Materials and Reagents:

- Botanical raw material or extract

- Herbarium voucher specimen materials

- Solvents for extraction (e.g., methanol, ethanol, water)

- Reference standards for marker compounds

- LC-MS grade solvents and additives for analysis

Procedure:

- Literature Review & Planning: Research traditional usage, common species, plant parts, and preparation methods. Identify known bioactive compounds or characteristic markers [17].

- Sample Acquisition & Authentication: Source material from reputable suppliers. Collect a voucher specimen from the same lot, including as many plant parts as possible (roots, leaves, flowers). Deposit the authenticated voucher in a recognized herbarium for permanent reference [17].

- Chemical Characterization:

- Targeted Analysis: If active constituents are known, use targeted methods (e.g., HPLC-DAD, LC-MS/MS) to quantify these compounds and ensure compliance with existing monographs [17].

- Untargeted Analysis: For less-defined materials, employ untargeted metabolomics (e.g., UHPLC-QTOF-MS) to generate a comprehensive metabolite profile. Compare against commercial or in-house spectral libraries [17].

- Contamination & Adulteration Screening: Test for heavy metals, pesticides, mycotoxins, and potential adulterants with synthetic drugs using validated analytical methods [17].

- Stability & Batch Monitoring: Conduct accelerated stability studies under various conditions (temperature, humidity). Analyze multiple batches to establish reproducibility ranges for key markers [17].

The following workflow diagram visualizes the key stages of this characterization process.

Fig 1. Workflow for characterizing botanical natural products.

Innovative Technologies Closing the Gap

Emerging technologies are directly addressing historical barriers to NP research, offering solutions that align with both academic and industry priorities.

Table 3: Innovative Technologies and Their Applications

| Technology | Application in NP Research | Impact on Perception Gap |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Mining & Metagenomics | Uncovers cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters, predicts novel compounds without traditional extraction [7]. | Reduces reliance on bulk biomass, addresses supply bottlenecks. |

| AI & Machine Learning | Accelerates hit discovery, de-replication, and prediction of biosynthetic pathways [7]. | Increases efficiency and success rates, making NP research more competitive with synthetic libraries. |

| Synthetic Biology | Engineers microbial hosts for sustainable production of complex NPs [7]. | Solves supply and sustainability issues, enabling scalable production. |

| Network Pharmacology | Embraces multi-target action of NPs, providing a scientific framework for traditional medicine [18]. | Bridges philosophical divide between reductionist and holistic approaches. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NP Screening & Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Herbarium Voucher Specimen | Provides taxonomic verification and a permanent physical record of the plant material studied [17]. | Essential for publication and reproducibility. Must be deposited in a recognized herbarium. |

| Authenticated Reference Standards | Enables quantification of active constituents or marker compounds for quality control [17]. | Critical for targeted analytical methods (HPLC, LC-MS) to ensure consistency. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Probes | Used in metabolomic studies to trace biosynthetic pathways and identify novel metabolites [7]. | Aids in de-replication and understanding NP biosynthesis. |

| LC-MS/MS Solvents & Columns | High-purity solvents and specialized chromatography columns for separating complex NP mixtures [17]. | Required for high-resolution metabolomics and sensitive detection. |

| Genomic DNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality DNA from plant or microbial sources for genome mining and barcoding [7]. | Necessary for genetic authentication and biosynthetic gene cluster analysis. |

| HTS Assay Kits & Reagents | Standardized biochemical or cell-based assays for high-throughput screening of NP libraries [15] [7]. | Allows for comparison of NP hits against synthetic libraries in industry-standard formats. |

The industry-academia perception gap in natural product research stems from tangible technical challenges and strategic differences. However, the shared recognition of NPs' inherent potential, combined with powerful new technologies and standardized methodologies, provides a clear path forward. By adopting robust characterization protocols, leveraging innovations in genomics and AI, and embracing frameworks like network pharmacology, both sectors can bridge this divide. Fostering strategic partnerships built on mutual respect, clear intellectual property agreements, and shared goals is essential to revitalize natural products as a sustainable and innovative source of next-generation medicines [7] [19].

For researchers in natural product screening, navigating the legal landscape is as crucial as mastering the laboratory techniques. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and its supplementary agreement, the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-Sharing (ABS), form the core international framework governing how genetic resources are accessed and how benefits from their utilization are shared [20] [21].

These agreements operate on the principle that countries have sovereign rights over their natural resources [20] [22]. For a scientist, this means that the plant, microbial, or animal material you are investigating is not just a biological sample; it is a genetic resource subject to specific legal requirements. The primary objective of the Nagoya Protocol is the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources, thereby contributing to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity [21] [23]. Adherence to these protocols is not merely a legal formality but a fundamental aspect of ethical and reproducible research in drug discovery and natural product characterization.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: As an academic researcher conducting non-commercial natural product discovery, am I obligated to comply with the Nagoya Protocol? A: Yes. The obligations of the Nagoya Protocol apply to "utilization of genetic resources," which is defined to include "research and development on the genetic and/or biochemical composition of genetic resources" [21] [22]. This definition covers both commercial and non-commercial research. Many provider countries do not differentiate between pure and applied research in their access legislation. It is critical to comply with the legal requirements of the country providing the genetic resource, regardless of your research's commercial intent.

Q2: What is the most common pitfall for researchers when sourcing genetic materials from international collaborators? A: The most common pitfall is assuming that a Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) from a research institution or culture collection automatically covers all Nagoya Protocol compliance requirements. While an MTA is essential, the protocol requires Prior Informed Consent (PIC) from the competent national authority of the provider country and the establishment of Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT) that specifically address benefit-sharing [21] [22]. You must verify that your collaborator obtained these documents at the time of original collection and that their terms permit your intended use and subsequent transfers.

Q3: Our research involves screening a library of synthetic compounds derived from a natural product scaffold. Are these compounds subject to the Protocol? A: This is a complex, evolving area. The Nagoya Protocol applies to genetic resources and "traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources" [21]. If your synthetic library is based on a chemical structure from a genetic resource covered by the Protocol, it may be considered a subsequent application and fall within its scope. The definitive factor is the national legislation of the provider country. You must carefully review the specific terms of the MAT and PIC, which may define the scope of "derivatives" and "applications." When in doubt, seek legal advice and err on the side of caution.

Q4: Where can I find reliable and official information on a country's specific access requirements? A: The Access and Benefit-sharing Clearing-House (ABSCH) is the official platform established by the Nagoya Protocol for this purpose [24]. It is a key tool for providing legal certainty and transparency. On the ABSCH, you can find:

- National focal points and competent national authorities for each country.

- Domestic regulatory ABS requirements, permits, and relevant legislation.

- Internationally Recognized Certificates of Compliance (IRCC) which serve as proof that a resource was accessed legally [24] [22].

Q5: What happens if our research project transitions from basic research to a commercial application? A: The MAT you agreed upon at the start of your research must specifically address this scenario [21] [22]. The MAT should outline the benefit-sharing obligations triggered by commercialization, which could include monetary benefits (e.g., milestone payments, royalties) or non-monetary benefits (e.g., joint development, capacity building). If your initial MAT did not cover commercialization, you must re-engage with the provider to negotiate new terms. Retroactively seeking permission is a breach of the Protocol and can lead to serious compliance issues.

Common Errors and Solutions Table

The table below outlines common procedural errors and their solutions to help you troubleshoot compliance issues in your research workflow.

| Error Stage | Common Error | Potential Consequence | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Access | Assuming a country has no ABS legislation because it is not listed. | Accessing resources illegally, leading to compliance breaches. | Consult the ABS Clearing-House first, then contact the National Focal Point for definitive confirmation [24]. |

| Negotiation | Not specifying the scope of research and potential commercial applications in the MAT. | Disputes with the provider country when research evolves or commercializes. | Ensure MAT is clear, covers all phases of research (including commercialization), and includes dispute resolution clauses [21] [22]. |

| Documentation | Failing to keep detailed records of PIC, MAT, and permits and transferring materials to third parties without proper documentation. | Inability to demonstrate due diligence, breaking the chain of compliance. | Maintain a dedicated digital repository for all ABS documents. Use a Nagoya-compliant MTA for all transfers [21]. |

| Checkpoints | Not engaging with national checkpoints (e.g., at the grant application or patent filing stage). | Non-compliance is not caught early, leading to larger problems later. | Proactively declare due diligence to relevant national checkpoints as required by user country measures (e.g., in the EU) [21]. |

Experimental Protocols for Compliance

Objective: To establish the legal provenance of a genetic resource before it is acquired for research, ensuring compliance with the CBD and Nagoya Protocol.

Materials:

- Computer with internet access: For consulting online databases.

- ABS Compliance Documentation Tracker: A spreadsheet or electronic lab notebook (ELN) system with fields for key document details.

Methodology:

- Identify the Provider Country: Determine the country of origin of the genetic resource. For biological samples, this is the country from which the organism was originally collected from in-situ conditions [25].

- Consult the ABS Clearing-House:

- Access the ABSCH website.

- Search for the provider country's profile to identify its Competent National Authority (CNA) and review its national ABS laws and requirements [24].

- Determine Access Conditions:

- If the country has ABS measures, proceed to determine the process for obtaining Prior Informed Consent (PIC).

- If the country has no established measures, document this finding from the CNA or National Focal Point (NFP).

- Verify Source Compliance (if sourcing from a repository):

- When obtaining resources from a culture collection (e.g., DSMZ), request their Internationally Recognized Certificate of Compliance (IRCC) or equivalent proof that the resource was accessed in accordance with the provider country's PIC and MAT [21].

- Ensure the repository's MTA allows for your intended research use.

- Document the Process:

- Record all steps, including dates of website checks, communications with authorities, and copies of permits or certificates, in your ABS Compliance Documentation Tracker.

Protocol: Negotiating Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT)

Objective: To establish a legally sound contract that outlines the terms of access, use, and benefit-sharing for a genetic resource.

Materials:

- Draft MAT template: Often provided by the provider country's CNA.

- Research project outline: A clear description of the intended research, including possible commercial outcomes.

Methodology:

- Prepare a Research Plan: Draft a comprehensive yet clear description of your research. Specify if the work is non-commercial, has potential for commercialization, or is for taxonomic identification only.

- Identify Benefit-Sharing Options: Review the Annex of the Nagoya Protocol for a list of monetary and non-monetary benefits. Propose benefits that are appropriate and feasible for your project. Examples include [21] [22]:

- Non-monetary: Collaboration with scientists from the provider country, participation in product development, sharing of research results, and admittance to related training.

- Monetary: Upfront payments, royalties on net sales, or contributions to a conservation fund.

- Clarify Key Terms: Ensure the MAT explicitly defines:

- The genetic resource covered.

- The scope and field of use of the research.

- Provisions for third-party transfers.

- Rights to intellectual property.

- Terms for benefit-sharing triggered by specific events (e.g., publication, patenting, commercialization).

- Execute and Archive: Once negotiated and signed, store the final MAT with the PIC document. Ensure all relevant team members are aware of its terms and restrictions.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow a researcher should follow to legally access and utilize a genetic resource.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources and tools essential for navigating the regulatory framework, rather than the wet-lab reagents.

| Tool / Resource | Function & Utility in ABS Compliance | Key Considerations for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| ABS Clearing-House (ABSCH) [24] | The official online platform for information on ABS, national focal points, and competent national authorities. | Use it as the first point of verification for any country's ABS requirements. Always check for updated information. |

| Internationally Recognized Certificate of Compliance (IRCC) [24] [21] | Proof that a genetic resource was accessed in accordance with PIC and established MAT. It is registered in the ABSCH. | When sourcing from a repository, request the IRCC. This is your primary evidence of legal provenance. |

| Competent National Authority (CNA) [21] [22] | The entity within a provider country with the legal authority to grant access (PIC) and negotiate MAT. | All official communication and applications for access must go through the CNA. Do not rely on informal agreements. |

| Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT) Document [21] [22] | The binding contract that outlines the conditions of use, benefit-sharing, and third-party transfers. | This is the most critical document to protect your research. Ensure it is precise and covers all potential future uses. |

| Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) | A contract governing the transfer of tangible research materials between two organizations. | Your MTA must be consistent with and reference the underlying PIC and MAT. It cannot override or negate them. |

Advanced Analytical and Screening Technologies: A Practical Toolkit for Researchers

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

HPLC-MS/MS Troubleshooting

Q1: My LC-MS analysis shows significant signal suppression and high background noise. What could be the cause?

Signal suppression and high background noise are frequently linked to mobile phase contaminants and non-volatile additives [26].

- Solution: Ensure all mobile phase additives are of the highest purity and are volatile. Avoid non-volatile buffers like phosphate; instead, use volatile alternatives such as ammonium formate or ammonium acetate at concentrations typically around 10 mM [26]. Formic acid (0.1%) is a good volatile additive for controlling pH; however, be cautious with alternatives like trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) as they can cause significant signal suppression [26]. Always use a divert valve to direct only the analyte peaks of interest into the mass spectrometer, preventing contamination from the solvent front and the high organic wash portion of the gradient [26].

Q2: How can I confirm if a performance issue is with my LC-MS method or the instrument itself?

Implement a routine benchmarking procedure [26].

- Solution: Establish and regularly run a benchmarking method using a standard compound like reserpine. Perform five replicate injections to assess key parameters like retention time reproducibility, peak height, and shape [26]. If you encounter problems with your analytical method, run the benchmark. If the benchmark performs as expected, the issue lies with your method or sample preparation. If the benchmark fails, the problem is likely with the instrument itself [26].

Q3: What is the most critical step for optimizing MS parameters for my specific analytes?

Infusion tuning is essential for compound-dependent optimization [26].

- Solution: Directly infuse your analyte into the MS and optimize source parameters like voltages, gas flows, and temperatures. Do not rely solely on an autotune function. Perform an autotune followed by a manual tune for your specific analytes to achieve the optimum signal [26]. When adjusting parameters that generate a response curve, set the value on a "maximum plateau" where small variations do not cause large changes in response, ensuring method robustness [26]. Save individual tune files for different compound groups [26].

FTIR Spectroscopy Troubleshooting

Q4: My FTIR spectrum for a plant extract has poor resolution and undefined peaks. How can I improve the sample preparation?

Poor resolution can stem from inadequate purification of the crude extract or overly thick sample preparation.

- Solution: FTIR is a fast and non-destructive method for identifying functional groups in phytochemicals [27]. However, for complex plant extracts, further purification is often necessary. Prior to FTIR analysis, employ chromatographic techniques like HPLC to separate individual compounds or fractionate the extract [27]. This reduces spectral overlap from multiple concurrent compounds, leading to cleaner and more interpretable spectra. Ensure your sample is properly prepared for your chosen technique (e.g., as a dry film for ATR-FTIR or a pellet with KBr for transmission FTIR).

Q5: Can FTIR quantitatively determine the concentration of a specific flavonoid in my extract?

FTIR is primarily a qualitative or semi-quantitative technique for functional group identification [27].

- Solution: For accurate identification and quantification of specific compounds like flavonoids, FTIR should be combined with other techniques [27]. Use HPLC-DAD or LC-MS/MS for precise quantification [27]. FTIR is excellent for "fingerprinting" and confirming the presence of major functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carbonyl, unsaturated bonds) associated with compound classes like flavonoids, but it is not the preferred tool for exact concentration measurement in complex mixtures [27].

SEM-EDX Troubleshooting

Q6: My SEM-EDX analysis of my plant-synthesized nanoparticles shows a very weak signal for the metal. What might be wrong?

Weak signals can be caused by insufficient nanoparticle loading, thick or charging samples, or improper analysis conditions.

- Solution: Ensure your sample is conductive. For non-conductive biological samples, coating with a thin carbon layer is often necessary. For green-synthesized nanoparticles, confirm that the biosynthesis was successful and that nanoparticles are present on the surface [28]. Refer to the established protocol for Papilionanthe teres leaf extract synthesis as a reference [28]. Make sure the sample is dry and properly mounted. Increase the counting time or beam current to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, but be mindful of potential beam damage to the sample [29].

Q7: Why can't I detect light elements like carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen in my biological sample with EDX?

This is a fundamental limitation of standard EDX systems [29] [30].

- Solution: EDX has lower sensitivity for elements with low atomic numbers (below sodium) [30]. The X-rays from light elements are of low energy and are easily absorbed by air or the detector window. While detection is possible, it requires specialized detectors and can be challenging [29]. The presence of these light elements is often inferred, and techniques like FTIR or NMR are better suited for their direct detection and characterization in organic matrices [27].

Q8: My EDX spectral peaks for phosphorus and sulfur are overlapping. How can I resolve this?

Peak overlap is a common challenge in EDX analysis, as elements with adjacent atomic numbers can have overlapping X-ray energies [29].

- Solution: Use the manufacturer's software deconvolution tools to mathematically resolve the overlapping peaks [29]. Ensure your system is well-calibrated. In some cases, using a different X-ray line for identification (e.g., K vs. L lines) might help, though this is not always possible with biological samples. For critical analysis, complement EDX with a technique like NMR, which excels at distinguishing between different chemical environments of atoms like phosphorus-31 ( [31], [27]).

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

- Principle: Plant extracts contain phytochemicals that act as reducing and stabilizing agents to convert metal salts into nanoparticles.

- Materials: Fresh or dried plant leaves (e.g., Papilionanthe teres), silver nitrate (AgNO₃) solution, distilled water, laboratory glassware, centrifuge.

- Procedure:

- Extract Preparation: Wash, dry, and grind plant leaves. Prepare an aqueous extract by boiling the plant material in distilled water and filtering the mixture.

- Synthesis Reaction: Mix the filtered plant extract with an aqueous solution of AgNO₃ under constant stirring. The reaction can be monitored by a color change.

- Purification: Centrifuge the resulting nanoparticle suspension at high speed to pellet the nanoparticles. Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in distilled water. Repeat this washing step 2-3 times.

- Characterization: Analyze the purified nanoparticles using SEM-EDX for morphology and elemental composition, and FTIR to identify the functional groups of phytochemicals capping the nanoparticles [28].

- Principle: To preserve the native structure and elemental composition of a biological sample for analysis under the high vacuum of an electron microscope.

- Materials: Phosphate buffer, paraformaldehyde, osmium tetroxide, ethanol series, propylene oxide, epoxidic resin, ultramicrotome.

Procedure (Standard Resin Embedding):

- Primary Fixation: Fix a small tissue sample (~1 mm³) in buffered 4% paraformaldehyde to preserve structure.

- Post-fixation: Treat with 2% osmium tetroxide, which also adds conductivity.

- Dehydration: Pass the sample through a graded series of ethanol (30%, 50%, 70%, 95%, 100%) to remove water.

- Infiltration and Embedding: Transition the sample into propylene oxide and then infiltrate with epoxidic resin. Embed in fresh resin and polymerize in an oven.

- Sectioning: Use an ultramicrotome to cut ultrathin (~100 nm) or semi-thin sections.

- Analysis: Mount the sections on a suitable stub and analyze unstained under SEM-EDX to avoid interference from heavy metal stains [29].

Note: For elemental analysis, cryo-fixation (flash-freezing) is the gold standard to prevent loss or translocation of diffusible ions, but it is more technically demanding [29].

- Principle: High-performance liquid chromatography separates compounds in a complex extract, a diode array detector provides UV-Vis spectra, and tandem mass spectrometry enables identification and structural elucidation.

- Materials: HPLC-grade solvents (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile, water), volatile acids (e.g., formic acid), solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges, syringe filters, plant extract.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Defat and extract plant material using a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol). Pre-purify the crude extract using SPE to remove contaminants [26]. Filter the final extract through a 0.22 µm membrane filter before injection.

- LC Separation: Use a reversed-phase C18 column. Employ a binary gradient with a mobile phase A (e.g., water with 0.1% formic acid) and phase B (e.g., acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid). The gradient runs from low to high organic modifier [27] [26].

- DAD Detection: Acquire UV-Vis spectra throughout the run, which helps identify compound classes like flavonoids and phenolic acids based on their chromophores [27].

- MS/MS Analysis: Couple the HPLC outlet to the mass spectrometer via an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Use tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) to fragment precursor ions. This fragmentation pattern is a unique fingerprint for compound identification [27].

- Data Analysis: Compare retention times, UV spectra, precursor mass, and fragmentation patterns with those of authentic standards or databases.

Comparison of Analytical Techniques in Phytochemical Profiling

| Technique | Core Function | Key Information Obtained | Sample Requirements | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-MS/MS [27] | Separation, identification, and quantification of individual compounds. | Molecular weight, structural fragments, precise quantification. | Liquid extract, purified and filtered. | Complex operation; requires volatile mobile phases [26]; high instrument cost. |

| FTIR [27] | Identification of functional groups and chemical bonds. | Presence of functional groups (e.g., -OH, C=O, C-O); compound class fingerprint. | Solid (KBr pellet) or liquid film. | Difficult for complex mixtures without prior separation; semi-quantitative at best. |

| SEM-EDX [29] [30] | Morphological imaging and elemental analysis. | Surface topography, elemental composition (atomic no. >10), spatial distribution. | Solid, dry, conductive (often requires coating). | Cannot distinguish ionic states [29]; low sensitivity for light elements [30]; vacuum required. |

| NMR [27] | Elucidation of molecular structure and dynamics. | Detailed carbon-hydrogen skeleton; unambiguous structure determination. | Solubilized extract or pure compound. | Lower sensitivity than MS; requires relatively pure samples for full structural elucidation. |

Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Volatile Buffers (Ammonium formate/acetate) [26] | pH control in mobile phase without contaminating the MS ion source. | Use at concentrations ~10 mM; preferable to non-volatile phosphates. |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Pre-purification of crude plant extracts to remove contaminants. | Prevents column clogging and ion source contamination in LC-MS [26]. |

| HPLC-grade Solvents | Serve as the mobile phase for chromatography. | Low UV cutoff and high purity are essential for sensitive detection. |

| Formic Acid | A volatile acid additive to improve protonation and chromatography in LC-MS. | A common alternative to TFA, which can cause signal suppression [26]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Precursor salt for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles. | Reacts with phytochemicals in plant extracts to form Ag nanoparticles [28]. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Integrated Phytochemical Analysis

LC-MS Method Optimization

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an automated, robotic method that enables researchers to rapidly test thousands to millions of chemical, biological, or material samples for biological activity or specific properties [32] [33]. In drug discovery, HTS serves as a primary strategy to identify starting compounds ("hits") for small-molecule drug design campaigns, particularly when little is known about the target structure, which prevents structure-based drug design [34] [33]. The two fundamental approaches in antibacterial drug discovery are cellular target-based HTS (CT-HTS), which uses whole cells to identify intrinsically active agents, and molecular target-based HTS (MT-HTS), which uses purified proteins or enzymes to identify specific inhibitors [35].

Technical Comparison: Cellular vs. Molecular Target-Based Assays

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Cellular and Molecular Target-Based HTS Platforms

| Characteristic | Cellular Target-Based HTS (CT-HTS) | Molecular Target-Based HTS (MT-HTS) |

|---|---|---|

| Screening System | Whole living cells (can be 2D or 3D cultures) | Purified proteins, enzymes, or receptors |

| Biological Context | High physiological relevance; maintains cellular environment | Low physiological relevance; isolated system |

| Primary Advantage | Identifies compounds with cellular activity and permeability | Reveals direct target binding and specific mechanism |

| Primary Disadvantage | Target identification can be challenging | Hits may lack cellular activity due to permeability issues |

| Hit Validation Needs | Secondary screening to eliminate non-specific cytotoxic compounds | Secondary screening to eliminate pan-assay interference molecules (PAINS) |

| Throughput Potential | Generally lower due to biological complexity | Generally higher due to simplified system |

| Information Obtained | Phenotypic response, cell viability, pathway modulation | Direct binding, enzymatic inhibition, binding affinity |

Table 2: Technical Performance and Output Metrics

| Performance Metric | Cellular Target-Based HTS | Molecular Target-Based HTS |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Hit Rate | Approximately 0.3% with natural products [35] | <0.001% with synthetic libraries [35] |

| False Positive Sources | General cytotoxicity, off-target effects, assay interference | Chemical reactivity, metal impurities, assay technology artifacts, autofluorescence, colloidal aggregation [33] |

| Key Quality Control Measures | Cell viability assessment, morphology checks, multiplexed readouts | Counter-screens for promiscuous inhibitors, purity verification, dose-response confirmation |

| Data Complexity | High (multiple cellular parameters possible) | Lower (typically single parameter readouts) |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Assay Development and Validation

FAQ: What statistical measures should I use to validate my HTS assay before screening? The Z'-factor is an essential statistical parameter for assessing HTS assay quality. A Z'-factor above 0.5 is generally considered excellent, indicating a robust assay with good separation between positive and negative controls [32] [36]. Plate uniformity studies should be conducted over multiple days (3 days for new assays, 2 days for transferred assays) using Max (maximum signal), Min (background signal), and Mid (intermediate signal) controls to establish signal window stability and reproducibility [36].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Poor Z'-Factor Values

- Problem: Low Z'-factor (<0.5) indicating poor separation between controls.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- High signal variability: Optimize reagent concentrations, ensure consistent cell seeding density, verify incubation times and temperatures.

- Insufficient signal window: Increase assay dynamic range by adjusting detection parameters or using more sensitive reporters.

- Edge effects in microplates: Use plate seals to prevent evaporation, ensure proper humidity control during incubations.

- Reagent instability: Prepare fresh reagents daily, aliquot and freeze reagents properly, verify storage conditions.

Technical Artifacts and Interference

FAQ: Why do I get different results between cell-based and biochemical assays for the same compounds? Lack of concordance between cellular and enzyme activity is common [37]. In cellular assays, antimicrobial activity might actually result from off-target toxicity rather than specific target inhibition. Conversely, molecules active in molecular target assays may fail in cellular assays due to poor membrane permeability, efflux pump activity, or binding to intracellular proteins like albumin that reduce effective concentration [37]. Always confirm that enzyme hits translate to cellular target engagement.

Troubleshooting Guide: Managing Compound Interference in HTS

- Problem: High false positive rates due to compound interference.

- Common Interference Mechanisms & Solutions:

- Autofluorescence: Use red-shifted fluorophores or switch to luminescence-based detection methods [33].

- Chemical reactivity: Include counter-screens with detergent-based assays to identify promiscuous inhibitors [32] [33].

- Colloidal aggregation: Add non-ionic detergents (e.g., 0.01% Triton X-100) to assay buffer [33].

- Metal impurities: Use chelating agents in assays or pre-purify compound libraries [33].

- Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS): Apply computational filters to identify and remove known PAINS from hit lists [33] [35].

Natural Product-Specific Challenges

FAQ: What are the special considerations when screening natural product libraries? Natural product extracts present unique challenges including complex composition with molecules at varying concentrations, presence of colored compounds that interfere with detection, potential for antagonistic or synergistic effects between components, and high probability of rediscovering known compounds [35]. To address these issues: pre-fractionate complex extracts, use orthogonal detection methods (not reliant on absorbance), include dereplication strategies (early identification of known compounds), and employ mechanism-informed phenotypic screening with reporter genes [35].

Troubleshooting Guide: Natural Product Library Screening Issues

- Problem: Inconsistent activity in natural product screening.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Concentration variability: Standardize extraction methods, perform bioassay-guided fractionation.

- Non-specific binding: Add carrier proteins (e.g., BSA) to reduce non-specific binding.

- Carryover of interferents: Implement wash steps in cell-based assays, use longer incubation times to distinguish specific from non-specific effects.

- Rediscovery of known compounds: Implement early dereplication using LC-MS and NMR comparison to known compound databases.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Cell-Based Viability Assay (CT-HTS)

Purpose: To identify compounds that inhibit bacterial growth or kill pathogenic bacteria. Materials: Bacterial culture (e.g., S. aureus), compound library, 384-well microplates, culture medium, viability stain (e.g., resazurin), DMSO, automated liquid handler, plate reader. Procedure:

- Prepare compounds in DMSO in source plates (typical concentration: 10 mM).

- Dilute compounds in medium to working concentration (final DMSO ≤1%).

- Dispense bacterial suspension (~5×10^5 CFU/mL, 50 μL/well) into 384-well plates.

- Add compounds (0.1 μL from source plate using pintool), include controls: medium-only (background), DMSO (negative), known antibiotic (positive).

- Incubate 16-20 hours at 37°C.

- Add resazurin solution (5 μL of 0.15 mg/mL), incubate 2-4 hours.

- Measure fluorescence (Ex560/Em590).

- Calculate % inhibition = 100 × [1 - (Sample - Background)/(Negative Control - Background)].

Validation Parameters: Z'-factor >0.5, signal-to-background ratio >3, coefficient of variation <10% [36].

Protocol: Enzyme Inhibition Assay (MT-HTS)

Purpose: To identify compounds that inhibit specific enzymatic activity. Materials: Purified enzyme, substrate, compound library, assay buffer, 384-well microplates, DMSO, detection reagents. Procedure:

- Prepare enzyme solution in assay buffer (optimized concentration).

- Dispense compounds (0.1 μL from DMSO stock) to assay plates.

- Add enzyme solution (20 μL/well), pre-incubate 15 minutes.

- Initiate reaction with substrate solution (5 μL/well).

- Incubate appropriate time (determined by kinetic analysis).

- Stop reaction if needed, measure signal (absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence).

- Include controls: no enzyme (background), no inhibitor (negative control), known inhibitor (positive control).

- Calculate % inhibition = 100 × [1 - (Sample - Background)/(Negative Control - Background)].

Validation Parameters: Z'-factor >0.5, signal-to-background >5, linear reaction progress, appropriate Km for substrate [36].

HTS Workflow and Decision Pathways

HTS Platform Selection and Hit Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function in HTS | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | Assay vessel for high-density screening | Available in 96-, 384-, 1536-well formats; choice depends on throughput needs and available liquid handling capabilities [33] |

| DMSO | Universal solvent for compound libraries | Final concentration should be kept under 1% for cell-based assays unless demonstrated otherwise by compatibility testing [36] |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Precise dispensing of nanoliter to microliter volumes | Essential for reproducibility; robots from manufacturers like Tecan or Hamilton can significantly increase throughput and accuracy [32] |

| Fluorescent Dyes/Reporters | Signal generation for detection | Include viability indicators (resazurin), calcium-sensitive dyes (Fluo-4), FRET pairs; choice depends on assay compatibility and interference potential [34] |

| Cell Lines | Cellular context for CT-HTS | Use relevant cell types (primary, engineered reporter lines); consider 3D cultures for enhanced physiological relevance [38] |

| Purified Proteins/Enzymes | Targets for MT-HTS | Require validation of functionality and purity; stability under assay conditions must be established [34] |

| Control Compounds | Assay validation and normalization | Include known inhibitors/activators for both positive and negative controls; essential for Z'-factor calculation [36] |

Advanced Applications in Natural Product Research

Natural products present both opportunities and challenges for HTS campaigns. More than 50% of currently available antibiotics are derived from natural products, yet discovering new antibiotics from natural sources has seen limited success due to the rediscovery of known compounds and the complexity of natural extracts [35]. Innovative approaches are emerging to address these challenges:

Mechanism-Informed Phenotypic Screening: This strategy uses reporter gene assays that indicate which signaling pathways hits are interacting with, providing both phenotypic information and mechanism insight [35]. For example, imaging-based HTS assays can identify antibacterial agents based on biofilm formation ability or using reporters of antibacterial activity such as adenylate cyclase that releases upon cell lysis [35].

Virulence and Quorum-Sensing Targeting HTS: This approach screens for inhibitors of virulence factors rather than essential growth pathways, potentially reducing selective pressure for resistance. Successful examples include LED209, identified by screening 150,000 molecules using CT-HTS, which demonstrated successful in vivo antibacterial activity against Salmonella typhimurium and Francisella tularensis [35].

Biomimetic Conditions: Newer screening approaches attempt to mimic real infection environments to better study ligand-target interactions, enabling the design of more effective antibacterial drugs [35]. These systems better account for factors like protein binding, pH variations, and metabolic activity that affect compound efficacy in real-world applications.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Applications

Q1: What are the main advantages of using reporter gene assays (RGAs) for screening natural products compared to traditional methods?

Reporter gene assays offer several key advantages for screening bioactive compounds from complex natural product mixtures. They are highly versatile and reliable, providing a direct, functional readout of biological activity by linking a specific cellular pathway or response to the expression of an easily measurable reporter protein [39]. Unlike assays that merely show binding, RGAs can reveal whether a compound activates or inhibits a entire biological pathway, making them ideal for phenotypic screening [40]. Furthermore, RGAs, especially those using secreted reporters, are well-suited for high-throughput screening (HTS) platforms, allowing for the efficient testing of thousands of samples [40] [41]. They are also mechanism-of-action (MOA) related, which increases their value in characterizing how a natural product exerts its effect [41].

Q2: How do anti-virulence strategies differ from conventional antibiotics, and why are they promising for natural product research?

Conventional antibiotics typically target essential bacterial processes like cell wall synthesis, exerting strong selective pressure that drives antibiotic resistance. In contrast, anti-virulence strategies aim to disarm pathogens by targeting their virulence factors (VFs)—molecules that enable the bacteria to cause disease—without inhibiting growth or killing the bacteria [42] [43]. This approach is promising because it potentially reduces the selective pressure for resistance development [42] [44]. Natural products are an excellent source for anti-virulence compounds, as many plant-derived compounds, such as polyphenols and alkaloids, have been shown to effectively disrupt virulence mechanisms like quorum sensing (QS) and biofilm formation [44].

Q3: What is bioaffinity ultrafiltration, and when should I use it in my natural product screening workflow?

Bioaffinity ultrafiltration is a straightforward and practical method for rapidly identifying ligands from a complex natural extract that bind to a specific protein target. The process involves incubating the target protein with the extract, using ultrafiltration to separate the small molecule ligands bound to the protein from unbound components, and then identifying the bound ligands with techniques like UPLC-MS/MS [45]. You should use this method when you want to quickly isolate target-specific active compounds from a complex mixture without first performing lengthy separation of inactive components [45]. It is particularly useful for initial screening to "fish out" potential hit compounds that interact with a protein target of interest, such as screening an Oroxylum indicum extract for ligands that bind to the NDUFS3 protein [45].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Reporter Gene Assays

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Signal | Endogenous cellular enzyme activity interfering with the reporter [40]. | Use a secreted reporter (e.g., SEAP) and leverage its unique properties (e.g., heat stability) to inactivate endogenous enzymes [40]. |

| Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Low transfection efficiency or weak promoter activity. | Optimize transfection protocols; use a stronger or more specific promoter element to drive reporter expression. |

| High Variability Between Replicates | Inconsistent cell seeding, transfection, or assay conditions. | Standardize cell culture and assay protocols rigorously; use internal control reporters (e.g., dual-luciferase systems) to normalize for variability [40]. |

| False Positives in Screening | Compound cytotoxicity or non-specific activation of pathways. | Include cell viability assays in parallel; counterscreen against a different, non-specific reporter system to rule out general activators. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Anti-Virulence and Bioaffinity Assays

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-virulence compound shows no efficacy in vivo | Poor pharmacokinetic properties (rapid metabolism, inadequate delivery to infection site) [44]. | Explore advanced delivery systems like nanoparticles to improve stability and targeted delivery [44]. |

| Bioaffinity screening identifies too many non-specific binders | Non-specific, hydrophobic, or low-affinity interactions with the target protein. | Include stringent wash steps with buffers containing mild detergents or competitors; use a control (denatured) protein to identify and subtract non-specific binders. |

| Inability to identify molecular target of a natural product hit | The screening was a "black-box" phenotypic screen [40]. | Employ target deconvolution strategies such as affinity chromatography, protein microarrays, or RNA-seq to identify the pathways affected. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Secreted Reporter Gene Assay for Pathway Screening

This protocol outlines the steps for using a secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter to screen for compounds that modulate a specific signaling pathway.

- Reporter Construct Design: Clone the promoter or enhancer element of interest (e.g., one containing response elements for NF-κB, antioxidant response elements, etc.) upstream of the SEAP gene in a mammalian expression vector.

- Cell Line Development: Stably transfect the reporter construct into a relevant cell line (e.g., HEK293, HeLa). Select stable clones using an appropriate antibiotic (e.g., G418) and screen for clones with high inducible SEAP expression and low background.

- Assay Setup and Compound Screening:

- Seed the reporter cells in 96- or 384-well plates and allow them to adhere overnight.

- Treat cells with test compounds (e.g., natural product fractions), positive controls, and vehicle controls (e.g., DMSO).

- Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 16-24 hours).

- Signal Detection:

- Collect a small aliquot of the cell culture medium.

- Heat the medium sample (e.g., 65°C for 30 minutes) to inactivate endogenous alkaline phosphatases [40].

- Add a chemiluminescent SEAP substrate and measure the light emission using a luminometer. The signal is proportional to the pathway activity induced by the test compound.

Protocol 2: Bioaffinity Ultrafiltration Screening for Protein Ligands

This protocol describes a method to identify small molecules from a natural extract that bind to a purified protein target.

- Preparation:

- Purify the recombinant target protein (e.g., with a His-tag for easy purification) [45].

- Prepare the natural product extract and dissolve in a suitable buffer.

- Ligand Binding:

- Incubate the target protein with the natural product extract at a defined temperature (e.g., 37°C) for 30-60 minutes to allow ligand-protein binding.