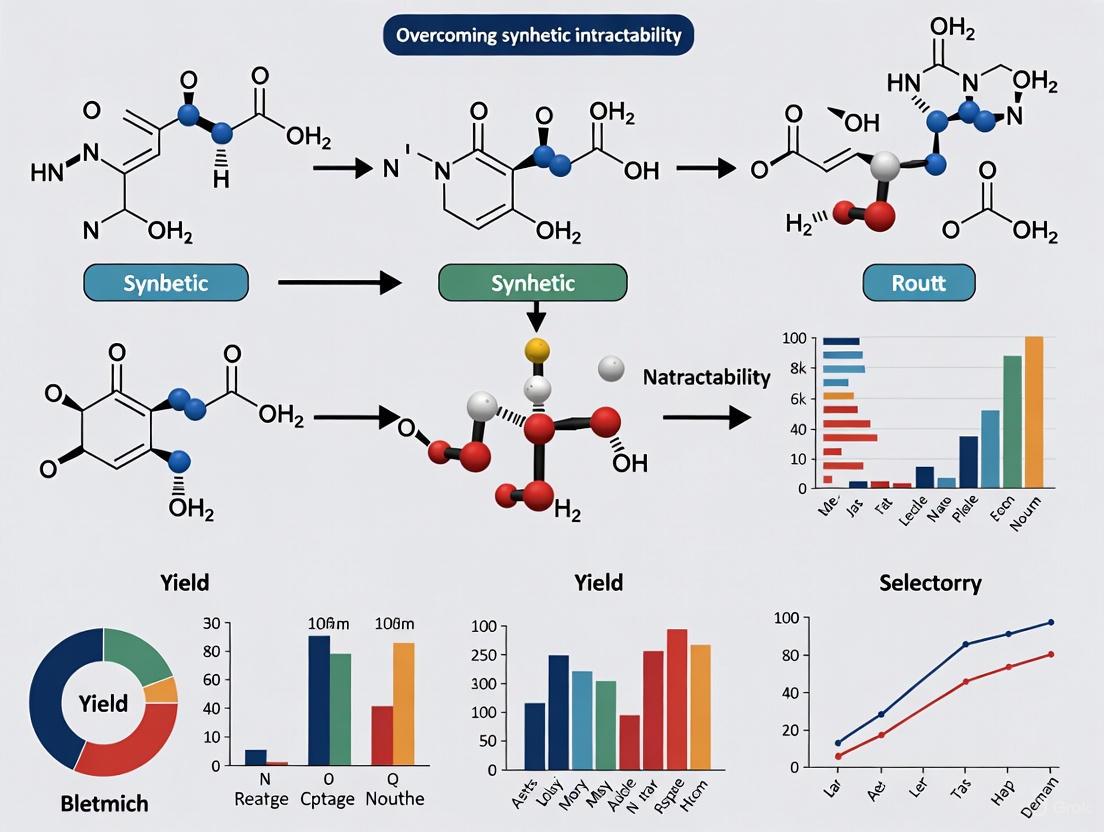

Overcoming Synthetic Intractability: New Strategies for Natural Product Development and Drug Discovery

This article addresses the critical challenge of synthetic intractability in natural product development, a major bottleneck in harnessing their potential for drug discovery.

Overcoming Synthetic Intractability: New Strategies for Natural Product Development and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of synthetic intractability in natural product development, a major bottleneck in harnessing their potential for drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive roadmap from foundational concepts to advanced applications. We explore the computational and chemical roots of intractability, detail cutting-edge methodological solutions like Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD) and C–H activation, and offer troubleshooting strategies for optimization. The scope also covers rigorous validation techniques and comparative analysis of traditional versus modern approaches, synthesizing key insights to guide the development of previously 'undruggable' targets into viable clinical candidates.

Defining the Challenge: The Roots of Synthetic Intractability in Natural Products

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does it mean for a problem in network biology to be NP-hard? An NP-hard problem is at least as hard as the hardest problems in the NP (Non-deterministic Polynomial time) class [1]. In practical terms for researchers, this means that as your biological network (like a protein-protein interaction or metabolic network) grows in size, the time required to find an exact solution increases exponentially rather than polynomially. For example, finding a minimum set of genes that control a metabolic pathway is often an NP-hard problem.

Q2: I need to find an optimal set of drug targets in a metabolic network. Why does my computation time become unmanageable? You are likely facing an NP-hard problem. The number of possible subsets of genes or proteins to test grows combinatorially with the size of your network. Verifying a given solution might be quick, but exhaustively checking all possible solutions to find the best one is computationally intractable for large networks [1]. This is a classic characteristic of NP-hard problems.

Q3: Are all complex problems in network biology NP-hard? No. Many complex problems are tractable (in class P), meaning they can be solved in polynomial time [1]. However, key problems central to natural product research are NP-hard, such as identifying the optimal scaffold for a synthetic pathway or finding the most influential nodes in a large gene regulatory network. Determining your problem's complexity class is the first troubleshooting step.

Q4: What practical strategies can I use to overcome synthetic intractability in my research? Since exact solutions for NP-hard problems are often impractical, researchers employ strategies like:

- Heuristics: Algorithms that find good, but not necessarily perfect, solutions in a reasonable time frame.

- Approximation Algorithms: Algorithms that provide provable guarantees on how close their solution is to the optimal one.

- Parameterized Algorithms: Algorithms that isolate the exponential complexity to a specific parameter of the network (e.g., treewidth), making them efficient for sparse or structured networks.

Q5: How can I verify that my heuristic solution for a network biology problem is reliable? While you cannot easily check if a heuristic found the best solution, you can validate its biological plausibility and robustness. Techniques include:

- Cross-validation: Using different subsets of your network data to test stability.

- Comparison to Null Models: Testing your solution against randomized networks.

- Experimental Validation: Using wet-lab experiments to confirm key predictions derived from the computational solution.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Exponentially Growing Computation Time for Pathway Analysis

Symptoms:

- Simulation runtime increases dramatically with a small increase in network nodes (e.g., from 50 to 70 genes).

- The software hangs or runs out of memory when analyzing full-scale networks.

Diagnosis: The analysis task is likely NP-hard. The algorithm is probably attempting to find an exact solution by exploring a solution space that grows exponentially.

Resolution:

- Problem Reformulation: Check if your biological question can be answered by a related, easier problem. For instance, instead of finding the global optimum, aim for a local optimum.

- Employ Heuristics: Switch from exact algorithms (like brute-force search or integer linear programming) to heuristic methods such as genetic algorithms, simulated annealing, or greedy randomized adaptive search procedures (GRASP).

- Leverage High-Performance Computing (HPC): If an exact solution is absolutely necessary, parallelize the computation across an HPC cluster to reduce wall-clock time.

Issue: Inconsistent Results from Different Optimization Algorithms

Symptoms:

- Two different software tools or algorithms return different "optimal" solutions for the same network and objective function.

- Small changes in initial parameters lead to vastly different outcomes.

Diagnosis: This is a common indicator of using heuristic solvers on a complex, multi-modal fitness landscape, which is typical for NP-hard problems. Different algorithms may get stuck in different local optima.

Resolution:

- Algorithm Consensus: Run multiple heuristic algorithms with different starting points and identify the solution(s) on which they converge.

- Ensemble Methods: Combine results from several algorithms to create a more robust, aggregated solution.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Systematically vary the input parameters to understand which factors most strongly influence the result and to build confidence in a stable solution.

Issue: Memory Overflow During Network Simulation

Symptoms:

- Software crashes with "out of memory" errors.

- Inability to load large network models into analysis tools.

Diagnosis: The algorithm's memory usage is likely growing exponentially or quadratically with network size, which is unsustainable for large networks.

Resolution:

- Data Compression: Use sparse matrix representations for network adjacency matrices.

- Disk-Based Storage: Utilize tools that can swap parts of the data to disk when not actively processed.

- Network Reduction: Apply network pruning techniques to remove low-degree or peripheral nodes that contribute less to the core network dynamics you are studying.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Heuristic Approach for Identifying Critical Nodes

Objective: To find a near-optimal set of critical nodes (e.g., drug targets) in a large-scale biological network using a greedy heuristic.

Workflow:

Methodology:

- Input: A network graph ( G = (V, E) ) and an objective function ( F(S) ) to maximize (e.g., disruption of a pathogen's metabolic network).

- Initialization: Start with an empty solution set ( S = \emptyset ).

- Iteration: a. For every node ( v ) not in ( S ), compute the gain ( F(S \cup {v}) - F(S) ). b. Select the node ( v^* ) with the highest gain. c. Add ( v^* ) to the set ( S ).

- Termination: Repeat until the solution set ( S ) reaches a predefined size ( k ) or the gain falls below a threshold.

- Output: The set ( S ) of ( k ) critical nodes.

Protocol 2: Metabolomic Validation of Predicted Targets

Objective: To experimentally validate computationally predicted drug targets from an NP-hard optimization in a microbial system.

Workflow:

Methodology:

- In Silico Prediction: Use a heuristic algorithm (see Protocol 1) to identify a set of potential enzyme targets ( T1, T2, ..., T_n ) in a metabolic network.

- Microbial Culture: Grow the target organism (e.g., a pathogenic bacterium) in a controlled bioreactor.

- Target Inhibition: Apply specific inhibitors for the predicted enzyme targets ( T_i ) to the culture.

- Metabolite Quenching: At defined time intervals, rapidly quench cell metabolism to capture the metabolic state.

- LC-MS Analysis: Perform Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) on the quenched samples to quantify metabolite abundances.

- Data Integration: Compare the measured metabolite changes (e.g., accumulation of substrates, depletion of products) with the predictions from the computational model. A strong correlation validates the prediction.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and computational tools used in the featured experiments.

| Item Name | Function in Research | Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gurobi Optimizer | Solver for mathematical programming problems (MIP, QP). | Used to find exact solutions for small-scale instances of NP-hard problems; provides a benchmark for heuristics. |

| Cytoscape | Open-source platform for network visualization and analysis. | Used to import, visualize, and pre-process biological network data before formal computational analysis. |

| NetworkX Library | Python package for the creation, manipulation, and study of complex networks. | Used to implement custom heuristic algorithms and perform network topology analysis (e.g., centrality, connectivity). |

| Specific Enzyme Inhibitors | Compounds used to experimentally perturb predicted targets in a metabolic network. | Must be highly specific to the predicted enzyme target to minimize off-target effects during validation. |

| LC-MS System | Analytical chemistry technique for identifying and quantifying metabolites. | Used in metabolomic validation protocols to measure the biochemical outcome of target inhibition. |

Complexity Classes in Computational Biology

The table below summarizes key complexity classes and their relevance to computational biology, providing a framework for diagnosing computational challenges [1].

| Complexity Class | Key Characteristic | Example in Network Biology |

|---|---|---|

| P | Easily solvable in polynomial time [1]. | Calculating the shortest path between two nodes in a network. |

| NP | "Yes" answers can be verified in polynomial time, but finding a solution may be hard [1]. | Verifying that a given set of genes is a vertex cover for a protein interaction network. |

| NP-hard | At least as hard as the hardest problems in NP. All NP-hard problems are not in NP [1]. | Finding the smallest possible set of genes that is a vertex cover (Vertex Cover Problem). |

| NP-complete | A problem that is both NP and NP-hard; these are the hardest problems in NP [1]. | The Boolean Satisfiability Problem (SAT), which can model many network logic problems. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What does 'synthetically intractable' mean in natural product chemistry? A compound is deemed synthetically intractable when its complex molecular architecture presents overwhelming challenges for efficient chemical synthesis in a laboratory. These hurdles can include densely packed functional groups, numerous chiral centers, or unusually reactive and unstable structures that make traditional synthetic routes too long, inefficient, or low-yielding to be practical for development [2] [3].

Why is overcoming synthetic intractability important for drug discovery? Natural products are a historic and enduring source of chemical information for medicine [3]. From 1981 to 2019, 41.9% of all new FDA-approved drugs were derived from natural sources [4]. Overcoming synthetic intractability is crucial because it unlocks access to these biologically validated, complex scaffolds that often possess unique therapeutic activities, such as in oncology, antimicrobials, and antifungals [4].

My natural product target has a very rigid, complex core. What synthetic strategy should I consider? For complex, rigid cores, you should investigate strategies that prioritize the essential functional elements for bioactivity. Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS) is particularly valuable here, as it uses the natural product's core as a "privileged" starting point for designing a more synthetically accessible library of analogues that retain the core's biological relevance [3].

I've identified a promising fragment hit, but it's synthetically challenging to elaborate. What can I do? This is a common challenge. The strategy of Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD), as pioneered by companies like Astex Pharmaceuticals, directly addresses this. It involves investing in innovative synthetic organic chemistry methodologies specifically designed to elaborate polar, unprotected fragments. Early consideration of synthetic feasibility is as critical as optimizing binding affinity for progressing a fragment hit [2].

What analytical tools can help me characterize complex natural product mixtures without full isolation? Advanced NMR and mass spectrometry platforms are designed for this exact challenge.

- The MADByTE platform uses 2D-NMR (TOCSY and HSQC) on complex mixtures to identify "spin system features," creating a chemical similarity network for dereplication and prioritization [5].

- Modern Mass Spectrometry approaches, including metabolomics and imaging, allow for the structural characterization of components directly in complex mixtures and even at single-cell resolution [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Yield or Failure in a Key Bond-Forming Step

Potential Cause: Excessive Structural Complexity and Steric Hindrance The target molecule may possess a high density of functional groups or stereocenters in a confined space, leading to severe steric hindrance that prevents key reactions from proceeding.

Solution Checklist:

- Re-evaluate Synthetic Strategy: Consider a Function-Oriented Synthesis (FOS) approach. Focus on synthesizing a simplified analogue that contains only the proposed essential structural features necessary for bioactivity, rather than the full natural product [3].

- Employ Milder Reaction Conditions: If the natural product contains sensitive functional groups, switch to metal-free or redox-neutral reactions to prevent decomposition.

- Utilize Computational Prediction: Before committing to synthesis, use quantum mechanical calculations (e.g., GIAO-DFT) to predict 13C NMR chemical shifts of your proposed synthetic intermediates. This can help you identify if the planned route is leading to the correct structure early on [6].

Problem: Inability to Assign Stereochemistry

Potential Cause: Limited Quantity of Isolated Material or Complex NMR Spectra Traditional 1D NMR may be insufficient for determining the relative configuration of multiple chiral centers in a complex molecule, especially in a mixture.

Solution Checklist:

- Acquire Advanced 2D-NMR Data: Perform TOCSY and ROESY/NOESY experiments. TOCSY can identify protons within the same spin system, while ROESY/NOESY provides through-space correlations critical for determining relative stereochemistry [5].

- Apply Quantum Mechanical Calculations: Implement a parameterized protocol for 13C NMR chemical shift calculation. As demonstrated for terpenes, this involves:

- Conducting a conformational search (e.g., using Monte Carlo/MMFF).

- Optimizing geometries and calculating NMR shielding constants (σ) using GIAO-DFT methods (e.g., mPW1PW91/6-31G(d)).

- Applying a class-specific scaling factor to correct systematic errors by linear regression against experimental data of known compounds [6].

- Leverage Mixture Analysis Platforms: Use a platform like MADByTE, which applies TOCSY and HSQC to complex mixtures to define discrete substructures, helping to deconvolute overlapping signals and assign structures without pure isolation [5].

Problem: Re-isolating Known Compounds (Dereplication)

Potential Cause: Inefficient Prioritization of Novel Chemistry from Complex Extracts Time and resources are wasted on the isolation and structural elucidation of already-known natural products.

Solution Checklist:

- Create a Chemical Similarity Network: Use the MADByTE platform workflow (detailed below) to analyze your extract library. This groups prefractions based on shared NMR spin system features, allowing you to quickly identify unique chemistries and prioritize novel compounds for isolation [5].

- Integrate MS and NMR Metabolomics: Combine HR-MS data with NMR-based similarity networking. Mass spectrometry can rapidly screen for known molecular formulas, while NMR similarity analysis can group compounds by structural family, even for novel scaffolds not present in any database [5] [4].

Problem: Promising Fragment Hit is Synthetically Intractable

Potential Cause: The fragment core lacks straightforward synthetic handles for chemical elaboration, making optimization prohibitively difficult.

Solution Checklist:

- Prioritize Synthetic Tractability in Library Design: When building a fragment library, select fragments that not only follow the "rule of three" but also contain clear, synthetically accessible vectors for future growth [2].

- Invest in Innovative Synthesis: Dedicate research to developing new synthetic methodologies that can handle the elaboration of polar, unprotected fragments, which are often the most challenging [2].

- Utilize Structure-Based Design: If possible, obtain a high-resolution co-crystal structure of the fragment bound to the target protein. This will reveal the precise binding mode and highlight the most critical growth vectors, ensuring your synthetic efforts are focused and effective [2].

Experimental Protocols & Data

This protocol is designed for the untargeted analysis and dereplication of natural products in complex mixtures using 2D NMR.

1. Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition:

- Solvent: Use DMSO-d6 if biological assay data integration is required, as it is the standard solvent for screening. Methanol-d4 or chloroform-d can be used if they match the initial extraction solvent. Do not mix solvents across the sample set.

- NMR Experiments:

- Acquire non-uniform sampling (NUS) phase-sensitive HSQC (50% sampling rate). The phase-sensitive version allows for distinguishing CH/CH3 (positive) from CH2 (negative) signals.

- Acquire NUS TOCSY (50% sampling rate).

- Data Processing: Process FIDs using standard NMR software (apodization, linear prediction, zero filling, phase/baseline correction). Export peak-picked lists for both HSQC and TOCSY spectra.

2. MADByTE Data Processing Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the core steps of the MADByTE platform for creating and comparing chemical features from 2D-NMR data:

- Input: Peak-picked tables from TOCSY and HSQC spectra.

- Spin System Feature Creation: The platform integrates

1H-13Cconnectivity (HSQC) with1H-1Hscalar coupling (TOCSY) to define discrete substructures present in each sample. - Feature Matching: Spin system features are matched between all samples in the set to identify shared and unique chemical entities.

- Output: A chemical similarity network that visualizes the chemical relationships between samples, enabling dereplication and bioactivity prioritization.

This protocol uses quantum mechanics to calculate NMR chemical shifts for structural validation, with parameters developed for terpenes.

1. Conformational Search and Selection:

- Perform a random conformational search using the Monte Carlo method and the MMFF force field.

- Select all conformations within an initial energy cutoff of 10 kcal mol−1.

- For these, perform single-point energy calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level.

- Select conformers within 5 kcal mol−1 for geometry optimization and frequency calculations.

- Finally, choose conformers with relative Gibbs free energies within 3 kcal mol−1 for the NMR calculation step.

2. NMR Calculation and Scaling:

- Calculate population-averaged

13Cnuclear magnetic shielding constants (σ) for the selected conformers using the GIAO method at the mPW1PW91/6-31G(d) level of theory, applying Boltzmann statistics at 298 K. - Calculate chemical shifts (δcalc) as δcalc = σTMS – σ, where σTMS is the shielding constant of tetramethylsilane (TMS) calculated at the same level.

- Apply a class-specific scaling factor (derived from a linear regression of calculated vs. experimental shifts for a training set of sesquiterpenes) to obtain the final scaled chemical shifts (δscal). The formula is: δscal = a × δ_calc + b, where

aandbare the slope and intercept from the linear regression.

The workflow for this computational protocol is summarized below:

Comparison of Computational NMR Methods

| Method | Key Theory | Best For | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameterized Protocol [6] | GIAO-DFT (mPW1PW91) | Specific classes (e.g., Terpenes) | High accuracy for the class it was designed for, affordable cost. | Requires development of a class-specific scaling factor. |

| SMART Platform [5] | Convolutional Neural Networks | Broad, single compounds | Identifies structurally similar molecules from a large library; does not require a single structure as a starting point. | Limited by the coverage of its reference database. |

| Tool / Resource | Function in Research | Example / Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| MADByTE Platform [5] | Untargeted analysis of complex NP mixtures via 2D-NMR. | Groups samples by shared NMR spin systems; no proprietary database required. |

| Fragment Libraries [2] | Provides starting points for FBDD against challenging targets. | Follows the "Rule of 3" (MW <300, low lipophilicity); high ligand efficiency. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software [6] | Calculates NMR parameters to validate proposed structures. | Uses GIAO-DFT methods (e.g., in Gaussian 09) with empirical scaling. |

| DrugBank [7] | Database of drug and drug target information. | Provides detailed drug mechanisms, structures, and target data for dereplication. |

| SciFinder [8] | Comprehensive database for chemical literature and substances. | Essential for searching known compounds and reactions to plan synthesis. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What makes a protein-protein interface considered 'undruggable'? PPIs have often been classified as 'undruggable' because their interfaces are typically large, flat, and lack deep, well-defined binding pockets, which makes it difficult for small molecules to bind with high affinity [9] [10]. Unlike traditional targets like enzymes, PPI interfaces often do not have endogenous small-molecule ligands to serve as a starting point for drug design [10].

FAQ 2: What are the main strategies for targeting 'undruggable' PPIs? Two primary strategies have emerged. The first is to target allosteric sites—regions topologically distinct from the PPI interface—to modulate the interaction [9]. The second involves using advanced modalities like Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD), which uses small molecules to tag proteins for degradation by the cell's own proteolytic systems, thus overcoming the need to directly inhibit a difficult binding site [11].

FAQ 3: How can computational tools help in overcoming the druggability gap? Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) and artificial intelligence (AI) can significantly accelerate the discovery of PPI modulators. AI models like AlphaFold can predict protein structures with high accuracy, aiding in druggability assessments and structure-based drug design [12]. Furthermore, virtual screening and machine learning can help identify potential allosteric sites and optimize lead compounds [12] [13].

FAQ 4: What is synthetic lethality and how does it relate to targeted cancer therapy? Synthetic lethality occurs when the simultaneous disruption of two genes leads to cell death, while disruption of either gene alone does not [14] [15]. This concept is exploited in cancer therapy to selectively target cancer cells with a specific mutation (e.g., in BRCA1/2) by inhibiting its synthetic lethal partner (e.g., PARP), leaving healthy cells relatively unharmed [14] [15].

FAQ 5: Why are PPI stabilizers more challenging to develop than inhibitors? PPI stabilizers, which enhance the interaction between two proteins, present a more complex challenge than inhibitors. Stabilizers often act allosterically, and their binding site may not be readily apparent. They must also be identified under conditions that favor the stabilized complex, which is more difficult to screen for compared to disruptive inhibitors [13].

Troubleshooting Experimental Guides

Challenge 1: Flat and Featureless PPI Interfaces

Problem: The target PPI interface is shallow and lacks obvious pockets for small-molecule binding, leading to low-affinity hits.

Solution & Workflow: Implement an integrated strategy that combines computational pocket prediction with experimental techniques to identify and validate cryptic or transient binding sites.

Recommended Protocol:

- Computational Binding Site Analysis:

- Fragment-Based Screening:

- Screen a library of low molecular weight fragments against the target protein using biophysical techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or NMR.

- Fragments, due to their small size, can bind to sub-pockets within the large PPI interface that larger compounds cannot access [13].

- Hit Validation and Optimization:

- Co-crystallize confirmed fragment hits with the target protein to determine their exact binding mode.

- Use structure-guided chemistry to link adjacent fragments or grow fragments into larger, higher-affinity lead compounds [13].

The following workflow outlines this integrated approach to tackle flat PPI interfaces:

Challenge 2: Identifying and Validating Allosteric Modulators

Problem: Directly targeting a PPI interface has failed; you need to identify alternative, allosteric sites to modulate the interaction.

Solution & Workflow: Systematically discover and characterize allosteric sites that can inhibit or stabilize the PPI upon ligand binding.

Recommended Protocol:

- Allosteric Site Detection:

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS):

- Perform a HTS of diverse compound libraries, including those enriched for "PPI-friendly" chemotypes (e.g., more chiral centers, higher molecular weight), using a functional assay that reports on the PPI [13].

- Mechanistic Validation:

- Confirm allosteric modulation using techniques like Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS), which can detect ligand-induced conformational changes throughout the protein [9].

- Use mutagenesis to show that disrupting the allosteric site, but not the orthosteric interface, abrogates the effect of the modulator [9].

The diagram below illustrates the strategic decision process for PPI modulation:

Challenge 3: Implementing a Synthetic Lethality Screen

Problem: You need to identify genes that are synthetically lethal with a specific cancer mutation to discover new, selective therapeutic targets.

Solution & Workflow: Use combinatorial CRISPR-Cas9 screening to systematically knock out gene pairs in a high-throughput manner.

Recommended Protocol:

- Library Design:

- Design a dual-guide RNA (dgRNA) library targeting a focused set of genes (e.g., DNA repair genes, kinases) or the entire genome alongside your gene of interest (e.g., a mutated tumor suppressor) [15].

- Cell Transduction and Selection:

- Transduce a cancer cell line (harboring the mutation of interest) with the dgRNA library using a lentiviral system at a low MOI to ensure one integration per cell.

- Select transduced cells with puromycin for 3-5 days [15].

- Screen and Analysis:

- Culture the selected cells for 2-3 weeks, allowing cells with lethal gene pair knockouts to drop out of the population.

- Harvest genomic DNA at the start and end of the culture period. Amplify and sequence the integrated gRNA regions.

- Identify synthetically lethal pairs by quantifying the depletion of specific dgRNAs in the end population compared to the start population using specialized analysis pipelines (e.g., MAGeCK) [15].

Data Presentation: PPI Druggability Classification

The table below summarizes a proposed classification system for PPI druggability based on computational assessment with SiteMap, which can help set realistic expectations at the start of a project [10].

| Druggability Class | Dscore Range | Binding Site Characteristics | Example PPI Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very Druggable | > 1.00 | Well-defined, deep pocket; high hydrophobicity [10] | Bcl-2, Bcl-xL [10] |

| Druggable | 0.89 – 1.00 | Significant pocket character; amenable to ligand binding [10] | HDM2, XIAP [10] |

| Moderately Druggable | 0.80 – 0.88 | Shallower, less enclosed pocket [10] | MDMX, VHL [10] |

| Difficult / Poorly Druggable | < 0.80 | Flat, featureless, and hydrophilic interface [10] | IL-2, ZipA [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Technology | Function / Application | Key Utility in Overcoming Intractability |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial CRISPR Libraries [15] | High-throughput screening of synthetic lethal gene pairs. | Enables systematic identification of context-specific genetic vulnerabilities in cancer cells. |

| Fragment Libraries [13] | Screening low molecular weight compounds to bind sub-pockets. | Useful for mapping the bindable surface of large, flat PPI interfaces. |

| PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) [11] | Bifunctional molecules that recruit a protein to an E3 ubiquitin ligase for degradation. | Modality shifts the goal from inhibition to degradation, targeting previously "undruggable" proteins. |

| AlphaFold & RosettaFold [12] [13] | AI-based protein structure prediction tools. | Provides reliable 3D models for targets with no experimental structure, enabling computational screening and druggability assessment. |

| SiteMap [10] | Computational tool for predicting and scoring binding sites on proteins. | Quantifies druggability (Dscore) to prioritize PPI targets and guides medicinal chemistry efforts. |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) [11] | Technology for screening vast numbers of compounds by linking each molecule to a DNA barcode. | Allows ultra-high-throughput screening of chemical space against purified protein targets to find initial hits. |

The majority-leaves minority-hubs (mLmH) topology is a fundamental architectural principle observed in virtually all molecular interaction networks (MINs), irrespective of organism or physiological context [16] [17]. This structure is characterized by an overwhelming majority (~80%) of 'leaf' genes that interact with only 1-3 other genes, and a small minority (~6%) of 'hub' genes that interact with at least 10 or more partners [16]. This case study explores the compelling hypothesis that the mLmH topology is not merely a byproduct of evolution but an adaptive solution to circumvent fundamental computational intractability in biological systems.

The underlying problem, formalized as the Network Evolution Problem (NEP), is computationally equivalent to the well-known (\mathcal{NP})-complete Knapsack Optimization Problem (KOP) [16]. In simple terms, an evolving biological system faces a problem of immense computational complexity when trying to determine the optimal set of genes to conserve, mutate, or delete to maximize beneficial interactions and minimize damaging ones network-wide. The emergence of the mLmH topology provides a sufficient and, assuming (\mathcal{P} \neq \mathcal{NP}), necessary condition for evolving systems to efficiently navigate this intractable optimization landscape [16].

Core Concepts: Definitions and Terminology

Molecular Interaction Networks (MINs) are graphs where nodes represent biological molecules (e.g., proteins, genes, metabolites), and edges represent direct physical or functional interactions between them [16] [17]. Analyzing their topology—the arrangement of nodes and edges—is a cornerstone of network biology [17].

The mLmH Topology (also historically referred to as 'scale-free-like') describes the specific, non-random connectivity pattern where a few nodes possess a very high number of connections, while the vast majority have very few. It is crucial to note that this study uses the term mLmH to sidestep the controversy surrounding strict power-law distributions in biological networks and focuses on the overarching pattern itself [16].

Computational Intractability refers to computational problems for which no efficient, exact algorithm is known, and the time required to find a solution grows exponentially with the problem size. The NEP is one such problem [16].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This section addresses common computational and conceptual challenges researchers face when studying network topology and intractability.

FAQ 1: Our model of a synthetic network does not converge to an mLmH topology. What could be wrong?

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate Fitness Function. The evolutionary algorithm's fitness function may not properly penalize network configurations that are computationally costly to optimize.

- Solution: Revisit the implementation of the NEP-based fitness function. Ensure it correctly calculates the benefit/damage scores for each gene based on the "Oracle Advice" and rigorously selects for configurations that maximize global benefit while minimizing damage. The fitness function should mirror the knapsack-like optimization pressure [16].

- Potential Cause 2: Insufficient Evolutionary Runtime.

- Solution: The emergence of mLmH is a result of long-term evolutionary optimization. Significantly increase the number of generations in your simulation and ensure population size is adequate to explore the solution space effectively.

- Potential Cause 3: Parameter Instability.

- Solution: Perform a parameter sensitivity analysis. Key parameters, such as the interaction potency (ρ) and the damage threshold, must be explored to find stable regions where mLmH emerges robustly [16].

FAQ 2: How can we distinguish an adaptive mLmH topology from a non-adaptive byproduct?

- Solution: Compare your network against appropriate null models.

- Generate Random Networks: Create Erdős–Rényi model networks with the same number of nodes and edges [17].

- Generate Preferential Attachment Networks: Create networks based on the Barabási-Albert model, which generates scale-free topologies through a non-adaptive growth mechanism [17].

- Compare Topological Metrics: Quantitatively compare your network's degree distribution, robustness to random node deletion, and its performance on the NEP with these null models. An adaptive mLmH topology should demonstrate superior performance in the NEP optimization compared to the random model and may show differences in higher-order structures from the pure preferential attachment model [16].

FAQ 3: How do we map a real-world biological dataset onto the NEP framework?

- Solution: Follow this experimental protocol:

- Network Reconstruction: Build a network from experimental data (e.g., yeast-two-hybrid for protein-protein interactions) [17].

- Define the Oracle Advice (OA): This simulates evolutionary pressure. The OA is a ternary sequence (A = (a{1},a{2},\dots,a{n})) where (aj = +1) (promote), (-1) (inhibit), or (0) (neutral) for each gene, based on phenotypic data (e.g., gene knockout studies or differential expression under a stress condition) [16].

- Assign Interaction Signs: Label each edge in your network as promotional (+1) or inhibitory (-1) using data from directed interaction studies or signaling databases.

- Calculate Benefit/Damage Scores: For each gene (g_i), sum the interactions that agree (benefit, green) or disagree (damage, red) with the Oracle Advice on the target gene, for both its outgoing (projected) and incoming (attracted) interactions [16].

The diagram below illustrates this mapping and scoring logic.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Simulating mLmH Emergence via an Evolutionary Algorithm

This protocol allows researchers to test the hypothesis that mLmH arises as an adaptation to computational intractability.

Objective: To generate synthetic MINs with mLmH topology using an evolutionary algorithm with an NEP-based fitness function.

Workflow Overview:

Materials & Computational Reagents:

- Software: A programming environment with graph manipulation and numerical computation libraries (e.g., Python with NetworkX, NumPy).

- Initial Network: A population of random networks (e.g., Erdős–Rényi graphs) [17].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initialization: Generate a population of random networks with a defined number of nodes and edges.

- Fitness Evaluation: For each network in the population, compute its fitness by solving the NEP.

- Apply a randomly generated Oracle Advice vector.

- Calculate the total network-wide benefit score (B{total}) and damage score (D{total}).

- Fitness (F = B{total} - \alpha \cdot \max(0, D{total} - \tau)), where (\tau) is a damage threshold and (\alpha) is a penalty weight [16].

- Selection: Rank networks by their fitness and select the top performers to proceed to the next generation.

- Variation (Mutation): Apply stochastic mutations to the selected networks:

- Node/Edge Addition/Deletion: Randomly add or remove nodes or edges.

- Interaction Sign Flip: Randomly change a promotional interaction to inhibitory, or vice versa.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 for thousands of generations.

- Analysis: Periodically measure the degree distribution of the fittest network in the population. Convergence is achieved when a stable mLmH distribution is observed (e.g., ~80% of nodes have degree ≤ 3).

Protocol: Quantitative Analysis of mLmH in Empirical Data

Objective: To quantify the mLmH topology in a real-world molecular network and compare its degree distribution to the synthetic networks generated in Protocol 4.1.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain a curated molecular interaction network from a public database (e.g., protein-protein interactions from STRING or BioGRID) [17].

- Degree Calculation: For each node in the network, calculate its degree (number of connections).

- Distribution Fitting: Plot the cumulative degree distribution. Categorize nodes into "leaves" (degree 1-3) and "hubs" (degree ≥ 10) [16].

- Statistical Comparison: Use statistical tests (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov) to compare the degree distribution of your empirical network with the synthetic network from Protocol 4.1 and with random control networks.

Data Presentation: Quantitative Findings

The following tables summarize the core quantitative data supporting the mLmH adaptation hypothesis, derived from the analysis of 25 large-scale molecular interaction networks [16].

Table 1: Characteristic Composition of mLmH-Possessing Networks

| Node Category | Degree Range | Average Percentage of Nodes | Proposed Functional Role in NEP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf Genes | 1 - 3 | ~80% | Specialized functions; low-cost optimization units within the knapsack problem. |

| Hub Genes | ≥ 10 | ~6% | System integration and stability; critical but costly variables in the optimization. |

| Intermediate | 4 - 9 | ~14% | Transitional or multi-functional roles. |

Table 2: Key Parameters for NEP Evolutionary Simulation

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Value/Range | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction Potency | (\rho) | 1 (default) | The strength/weight of a single interaction in benefit/damage calculations [16]. |

| Damage Threshold | (\tau) | User-defined | The maximum tolerable level of total network damage in the fitness function [16]. |

| Penalty Weight | (\alpha) | User-defined | A multiplier that scales the penalty for exceeding the damage threshold [16]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for mLmH and NEP Research

| Research Reagent / Resource | Type | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Interaction Databases (e.g., BioGRID, STRING, KEGG, BRENDA) [17] | Data | Source of empirically validated molecular interactions for building and validating network models. |

| Graph Analysis Software (e.g., NetworkX, Cytoscape) | Software | For constructing, visualizing, and computing topological metrics (degree, centrality) on networks. |

| Evolutionary Algorithm Library (e.g., DEAP, custom Python/Scripts) | Software | To implement the NEP fitness function and run the selection-mutation cycles for simulation. |

| Oracle Advice Phenotypic Datasets (e.g., from GEO, knockout phenotype databases) | Data | Provides the experimental basis for assigning promotion/inhibition states to genes in the NEP model. |

| High-Per Computing (HPC) Cluster | Hardware | Facilitates the computationally intensive task of running large-scale evolutionary simulations and solving NEP across many generations. |

Strategic Solutions: FBDD, C–H Activation, and Label-Free Target Deconvolution

Synthetic intractability—the formidable challenge of efficiently constructing complex natural product scaffolds—often stymies drug discovery efforts. Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD) provides a powerful strategy to circumvent this impasse. Instead of attempting to synthesize intricate natural product mimics directly, FBDD begins with small, simple chemical fragments (molecular weight typically ≤300 Da) that bind weakly to a biological target [18] [19]. These fragments serve as efficient starting points that are progressively grown or combined into potent, lead-like compounds [20]. This approach investigates a larger chemical space with fewer compounds and is applicable to challenging biological targets, including those involved in amino acid metabolism and other pathways targeted by natural products [21] [22]. By starting small and building complexity in a structured way, FBDD offers a rational path to overcome the synthetic hurdles inherent in natural product-based drug design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods for FBDD

Successful implementation of FBDD relies on a core set of specialized reagents, libraries, and methodologies. The table below summarizes the key components of the FBDD toolkit.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies in FBDD

| Item | Function/Description | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment Library | A curated collection of small molecules for screening [18] [19] [23]. | Molecular weight ≤300 Da; follows "Rule of Three" (ClogP ≤3, H-bond donors & acceptors ≤3, rotatable bonds ≤3); high solubility [18] [19]. |

| Poised Fragment Library | A specialized fragment library designed for rapid optimization [23]. | Contains points of diversity for derivatization; includes analogue series for early SAR [23]. |

| 19F-NMR Probe | A spectroscopic probe for ligand-observed NMR screening [20] [19]. | Used to detect and quantify weak fragment binding to the target protein. |

| Synpro Orange Dye | A fluorescent dye used in Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) [18]. | Binds hydrophobic regions of denatured protein; measures protein thermal stability (Tm) shifts. |

| Biosensor Chips | Solid surfaces for immobilizing biological targets in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [18]. | Enable real-time, label-free measurement of binding kinetics and affinity. |

| Isotopically Labeled Protein (15N, 13C) | Protein sample for protein-observed NMR screening [19]. | Allows monitoring of target protein signals to map fragment binding sites. |

Experimental Protocols: Core Methodologies for Fragment Screening and Optimization

Fragment Screening Using Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF)

Principle: DSF (or thermal shift assay) detects fragment binding by measuring the increase in the target protein's thermal stability. A fluorescent dye binds to hydrophobic patches exposed upon protein denaturation, and a positive binding event is indicated by an increase in the melting temperature (Tm) [18].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a solution containing the target protein (in µM range) and the fluorescent dye (e.g., Synpro Orange) in a suitable buffer [18].

- Fragment Addition: Add the fragment library compounds to individual samples at high concentrations (mM range) to compensate for weak affinity [18].

- Thermal Ramp: Load the samples into a real-time PCR instrument and slowly increase the temperature (e.g., from 25°C to 95°C) while continuously monitoring fluorescence.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Tm for each sample. A significant positive shift in Tm (ΔTm) for the protein-fragment mixture compared to protein alone indicates potential binding.

- Hit Confirmation: DSF hits must be confirmed using an orthogonal biophysical method (e.g., SPR or ITC) to rule out false positives [18].

Fragment Screening Using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Principle: SPR measures binding interactions in real-time without labels by detecting changes in the refractive index at a sensor surface where the target protein is immobilized [18].

Protocol:

- Immobilization: Covariantly immobilize the purified target protein onto a biosensor chip surface [18].

- Ligand Injection: Inject fragment solutions at various concentrations over the protein surface and a reference surface.

- Kinetic Measurement: Monitor the association phase as fragments bind and the dissociation phase as buffer flows over the chip. The resulting sensorgram provides data on association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rates.

- Affinity Calculation: The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is calculated from the ratio koff/kon. SPR is highly sensitive, requires low sample amounts, and provides valuable kinetic information for lead optimization [18].

Fragment-to-Lead Optimization Using Structure-Based Design

Principle: This critical phase involves using high-resolution structural data, primarily from X-ray crystallography, to guide the chemical elaboration of a weakly binding fragment into a potent lead compound [18] [19].

Protocol:

- Co-crystallization: Generate high-resolution X-ray crystal structures of the target protein in complex with the confirmed fragment hits.

- Binding Mode Analysis: Analyze the structure to identify key interactions between the fragment and the protein binding pocket. Note any adjacent unexplored sub-pockets.

- Fragment Growing: Chemically synthesize analogues by adding functional groups to the original fragment core to interact with nearby residues or sub-pockets. This is often guided by computational chemistry and high-throughput synthesis of hit expansion libraries [23].

- SAR Establishment: Test the new analogues in binding (e.g., SPR) and functional assays to establish Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR). Monitor ligand efficiency (LE) and lipophilic ligand efficiency (LLE) to ensure maintained optimization quality [23].

- Iterative Cycling: Repeat the cycle of structural analysis, chemical synthesis, and biological testing until a lead compound with the desired potency and properties is obtained.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is our fragment screening yielding an unusably high number of false positives?

Problem: A high rate of false positives in fragment screening, particularly with DSF, is a common issue that can derail a project.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Potential Cause 1: Compound Aggregation. Fragments can form colloidal aggregates that non-specifically denature proteins, causing a false positive Tm shift.

- Solution: Use a non-ionic detergent (e.g., 0.01% Triton X-100) in the assay buffer to disrupt aggregates. Confirm hits with an orthogonal method like SPR or NMR, which are less susceptible to aggregation artifacts [18].

- Potential Cause 2: Assay Conditions. Inappropriate buffer, pH, or protein concentration can lead to unstable baselines and unreliable ΔTm measurements.

- Solution: Optimize buffer conditions and protein quality beforehand. Always include a reference well with a known ligand as a positive control.

- Potential Cause 3: Chemical Reactivity. Some fragments may be chemically reactive and covalently modify the protein.

- Solution: Inspect the chemical structures of hits for reactive functional groups (e.g., aldehydes, Michael acceptors). Use a covalent binding assay or mass spectrometry to check for protein modification.

FAQ 2: Our confirmed fragment hit has very weak affinity (K_D > 1 mM). How can we efficiently optimize it into a viable lead?

Problem: Weak binding affinity is expected at the start of FBDD, but the path to optimization can be unclear.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Strategy 1: Obtain a Structural Anchor.

- Strategy 2: Employ a Poised Library.

- Action: If you have a "poised" fragment library with analogues, screen these compounds to rapidly generate initial SAR around the hit fragment. This can quickly indicate which regions of the fragment are tolerant of modification [23].

- Strategy 3: Computational Guidance.

- Action: Use computational methods like fragment docking or de novo design to suggest specific chemical groups to add during the "fragment growing" phase. This can help prioritize which synthetic directions to pursue [22].

- Strategy 4: Monitor Ligand Efficiency.

- Action: As you add atoms, calculate the Ligand Efficiency (LE = 1.4 * pIC50 / Number of Non-Hydrogen Atoms). Ensure that the increase in potency is not achieved at the expense of a dramatic drop in LE, which would indicate inefficient binding [23].

FAQ 3: Our fragments are insoluble at the high concentrations required for screening. How can we address this?

Problem: Fragment solubility is a common bottleneck, as screening often requires mM concentrations to detect weak binding.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Solution 1: Library Design.

- Action: For future libraries, enforce strict solubility criteria during selection, such as low ClogP and the presence of ionizable or polar groups [19].

- Solution 2: Modify Assay Conditions.

- Action: Increase the concentration of organic co-solvent (e.g., DMSO), but keep it consistent and low (typically ≤5%) to avoid denaturing the protein. Alternatively, use different buffer systems or adjust pH to improve solubility.

- Solution 3: Switch Screening Techniques.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

FBDD Hit-to-Lead Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative cycle of a Fragment-Based Drug Discovery campaign, from initial screening to optimized lead compound.

Overcoming Synthetic Intractability with FBDD

This diagram conceptualizes how the FBDD approach provides a solution to the problem of synthetic intractability in natural product-inspired drug discovery.

Key Quantitative Data in FBDD

The tables below consolidate critical quantitative parameters and data used to guide and evaluate FBDD campaigns.

Table 2: Key Physicochemical Parameters and Metrics in FBDD

| Parameter | Target Value / Range | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment Molecular Weight | ≤ 300 Da [18] [19] | Ensures low molecular complexity and high ligand efficiency from the start. |

| Fragment Affinity (K_D) | µM to mM range [18] [19] | Weak binding is expected for initial hits and is sufficient to begin optimization. |

| Ligand Efficiency (LE) | > 0.3 kcal/mol per heavy atom [23] | Measures binding efficiency relative to size; a key metric during optimization. |

| Lipophilic Ligand Efficiency (LLE) | Monitored during optimization [23] | Balances potency and lipophilicity; helps avoid overly hydrophobic molecules. |

| Rule of Three | MW < 300, ClogP ≤ 3, HBD ≤ 3, HBA ≤ 3 [18] [19] | A guideline for designing fragment libraries to ensure good solubility and drug-like properties. |

Table 3: Comparison of Primary Fragment Screening Methods

| Method | Throughput | Sample Consumption | Key Information Provided | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) | Medium-High [18] | Low (µM protein) [18] | Thermal Shift (ΔTm) | Susceptible to false positives; no structural info [18]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Medium [18] | Low (for immobilization) [18] | Binding affinity (KD), kinetics (kon, k_off) | Requires immobilization; can be sensitive to bulk effects. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Low-Medium | High (mg protein) | Binding confirmation, binding site mapping | Low throughput; requires significant protein. |

| X-ray Crystallography | Low (becoming higher) [19] | High (mg protein & crystals) | Atomic-resolution structure of complex | Requires crystallizable protein; lower throughput. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Low [18] | High (mg protein) [18] | Binding affinity (K_D), stoichiometry (n), enthalpy (ΔH) | Low throughput; high protein consumption [18]. |

The direct functionalization of carbon-hydrogen (C–H) bonds has emerged as a transformative strategy in organic synthesis, particularly for constructing complex natural products. This approach represents a paradigm shift from traditional step-intensive routes toward more economical and atom-efficient disconnections for C–C bond formation [24]. For researchers in natural product development, C–H activation provides powerful tools to overcome synthetic intractability by enabling late-stage functionalization and streamlining access to complex molecular architectures [25]. While traditional synthesis often requires pre-functionalized starting materials and protecting group manipulations, C–H activation allows direct conversion of inert C–H bonds into valuable functionalities, significantly enhancing synthetic efficiency [24]. This technical support document addresses common experimental challenges and provides troubleshooting guidance for implementing C–H activation methodologies in natural product synthesis.

Fundamental Concepts and Mechanisms

Terminology and Definitions

Understanding the precise terminology is crucial for effective communication and experimental design:

- C–H Activation: A specific mechanistic step involving direct cleavage of a C–H bond through interaction with a transition metal, resulting in a new carbon-metal bond [26].

- C–H Functionalization: A broader process involving replacement of a C–H bond with another element or functional group, often preceded by a C–H activation event [26].

- Sigma (σ) Complex: An intermolecular interaction where electron density from the σ-orbital of a C–H bond donates into an empty d-orbital on a transition metal [26].

- Agostic Interaction: An intramolecular interaction where a C–H bond coordinated to a metal through another primary metal-ligand interaction donates electron density into an empty metal d-orbital [26].

The Continuum of C–H Activation Mechanisms

The historical classification of C–H activation into distinct mechanistic categories is evolving toward a continuum model based on the degree of charge transfer during the transition state [26]. The classical mechanisms can be understood as special cases within this continuum:

This mechanistic continuum ranges from electrophilic to nucleophilic character, governed by the overall difference in charge transfer during the transition state rather than the formal oxidation state of the metal [26]. The key mechanisms include:

- Oxidative Addition: A low-valent metal center inserts into a C–H bond, cleaving the bond and oxidizing the metal [27].

- Electrophilic Activation: An electrophilic metal attacks the hydrocarbon, displacing a proton [27].

- Sigma-Bond Metathesis: Proceeds through a four-centered transition state where bonds break and form in a single concerted step [27].

- Concerted Metalation-Deprotonation (CMD) / Amphiphilic Metal-Ligand Activation (AMLA): Involves a ligated internal base (often carboxylate) simultaneously accepting the displaced proton intramolecularly [26] [27].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Low Conversion and Catalyst Inactivity

Problem: Reactions show poor conversion despite apparent standard conditions.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Conversion in C–H Activation

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution Approach | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| No reaction | Catalyst decomposition | Use fresh catalyst batches; exclude oxygen with rigorous Schlenk techniques | Test catalyst activity with standard reaction |

| Slow initiation | Catalyst pre-activation required | Add initiators (e.g., benzoquinone, Cu salts) or pre-warm catalyst | Monitor reaction start with in situ IR |

| Incomplete conversion | Catalyst poisoning by impurities | Purify substrates (chromatography, recrystallization); use distilled solvents | Analyze substrate purity by NMR/HPLC |

| Variable yields between batches | Moisture sensitivity | Dry glassware, molecular sieves, anhydrous solvents | Karl Fischer titration of solvents |

Experimental Protocol for Oxygen-Sensitive Reactions:

- Flame-dry reaction vessel under vacuum and cool under argon

- Weigh catalyst in glove box or use sealed catalyst stocks

- Transfer solvents via syringe through septa

- Use freeze-pump-thaw degassing (3 cycles) for added sensitivity

- Monitor reaction by TLC (aluminum-backed plates) or NMR sampling via cannula

Selectivity Issues (Regio-, Chemo-, Stereo-)

Problem: Lack of desired selectivity in C–H functionalization.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Table 2: Addressing Selectivity Challenges

| Selectivity Type | Governing Factors | Optimization Strategies | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regioselectivity | Electronic effects, steric bias, directing groups | Install weakly-coordinating directing groups; leverage inherent substrate bias; adjust steric bulk of ligands | 2-phenylpyridine derivatives [27]; Directed borylation [27] |

| Chemoselectivity | Relative bond strengths, catalyst specificity | Tune catalyst electronics; use redox-active directing groups; employ sequential functionalization | Palladium-catalyzed C–H activation/cyclization cascades [25] |

| Stereoselectivity | Chiral environment, catalyst control | Employ chiral ligands; use chiral carboxylic acids in CMD; design substrates with element of chirality | Asymmetric synthesis of (–)-deoxoapodine [25] |

Protocol for Directing Group Optimization:

- Screen directing groups with varying coordination strength (e.g., pyridine, amide, carboxylic acid)

- Evaluate solvent effects (apolar solvents often enhance coordination)

- Test temperature gradient (50-150°C) to balance kinetics and stability

- Assess removable/convertible directing groups for synthetic efficiency

Substrate Scope Limitations and Functional Group Tolerance

Problem: Reactions work on model systems but fail with complex natural product scaffolds.

Solutions:

- Electron-deficient heterocycles: Employ stronger oxidants (e.g., Ag(I) salts, PhI(OAc)₂) or switch to Ir/Rh catalysis

- Acid-sensitive groups: Replace common carboxylic acid additives with pivalic acid or use neutral conditions

- Oxidation-prone functionalities: Utilize Cu(II)/O₂ oxidant systems or electrochemical regeneration [25] [28]

- Sterically congested sites: Implement smaller ligand frameworks (e.g., phosphines instead of N-heterocyclic carbenes)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I distinguish between different C–H activation mechanisms experimentally?

A: Use a combination of techniques:

- Kinetic Isotope Effects (KIE): Primary KIE (>2) suggests C–H cleavage is rate-determining [26]

- Hammett Studies: Electronic dependence indicates charge development in transition state

- Intermediate Trapping: Isolate and characterize σ-complexes or metallocycles [26]

- Computational Studies: DFT calculations to map energy surfaces and charge distributions [26]

Q2: What are the most common catalyst decomposition pathways and how can I prevent them?

A: Primary decomposition pathways include:

- Reductive Degradation: Pd(II) to Pd(0) precipitation - prevent with oxidants (Ag(I), Cu(II), PhI(OAc)₂)

- Oxidative Degradation: Especially for lower-valent catalysts - exclude O₂, use anaerobic conditions

- Ligand Oxidation: Phosphine oxides from air sensitivity - use arylphosphines or N-based ligands

- Cluster Formation: Aggregation to inactive multimetallic species - add stabilizing ligands or use higher dilution

Q3: My C–H activation works stoichiometrically but not catalytically. What should I investigate?

A: This typically indicates issues with catalyst turnover:

- Oxidant inefficiency: Screen alternative oxidants (metal-based, hypervalent iodine, O₂)

- Product inhibition: Test if product inhibits catalyst (add product to starting reaction)

- Reductive elimination barrier: Modify ligands to facilitate this step

- Oxidant compatibility: Ensure oxidant doesn't degrade catalyst or substrate

Q4: How can I apply C–H activation to late-stage natural product functionalization without affecting sensitive functionalities?

A: Implementation strategies include:

- Directing group engineering: Design directing groups that coordinate without interfering

- Ligand-accelerated catalysis: Use electron-rich ligands to enhance reactivity at milder conditions

- Sequential functionalization: Employ orthogonal protection or leverage inherent reactivity biases

- Biocompatible conditions: Aqueous systems, physiological temperature, aerobic atmosphere [28]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for C–H Activation Methodologies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Precursors | Pd(OAc)₂, Pd(TFA)₂, [RuCl₂(p-cymene)]₂, [RhCpCl₂]₂, CpIr(CO)₂ | Generate active catalytic species | Acetate sources often facilitate CMD; TFA useful for electrophilic pathways |

| Oxidants | AgOAc, Ag₂CO₃, Cu(OAc)₂, PhI(OAc)₂, benzoquinone, O₂ (balloon) | Re-oxidize reduced catalyst | Silver salts often best for Pd; Cu systems cheaper; O₂ most atom-economical |

| Directing Groups | Pyridine, pyrazole, amide, carboxylic acid, oxime, N-oxide | Control regioselectivity via coordination | Weaker coordinating groups often provide broader scope |

| Additives | PivOH, AdCO₂H, CsOPiv, Cu(OPiv)₂, Mg(OTf)₂ | Accelerate C–H cleavage, enhance selectivity | Carboxylates crucial for CMD; Lewis acids activate electrophiles |

| Solvents | Toluene, DCE, 1,4-dioxane, TFE, DMF, HFIP | Medium for reaction, can influence mechanism | Apolar solvents enhance coordination; fluorinated alcohols facilitate electrophilic pathways |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Palladium-Catalyzed C–H Activation/Cyclization Cascade

Based on Tokuyama's synthesis of (–)-deoxoapodine [25]:

Materials: PdI₂ (10 mol%), K₃PO₄ (2.0 equiv.), KNTf₂ (1.5 equiv.), norbornene (1.2 equiv.), dry toluene, alkyl iodide substrate

Procedure:

- Charge flame-dried Schlenk tube with PdI₂ (11.2 mg, 0.03 mmol), K₃PO₄ (127 mg, 0.6 mmol), KNTf₂ (108 mg, 0.45 mmol)

- Add substrate (0.3 mmol) and norbornene (28.2 mg, 0.36 mmol) under argon

- Inject dry toluene (3 mL) via syringe

- Heat at 60°C with stirring for 12-24 hours

- Monitor by TLC (hexane/EtOAc 4:1)

- Cool, dilute with EtOAc (10 mL), filter through Celite

- Concentrate and purify by flash chromatography

Troubleshooting: If reaction stalls, verify norbornene quality (distill before use) and exclude oxygen. For acid-sensitive substrates, replace K₃PO₄ with CsOAc.

Electrochemical C–H Activation Setup

Protocol for oxidant-free conditions [28]:

Cell Configuration: Undivided cell, graphite anode (6 cm²), Pt cathode, n-Bu₄NPF₆ (0.1 M electrolyte)

Typical Procedure:

- Dissolve substrate (0.5 mmol) and catalyst (10 mol%) in solvent/electrolyte (10 mL)

- Purge with N₂ for 10 minutes

- Apply constant current (5-10 mA) for 4-8 hours

- Monitor conversion by TLC/GC-MS

- Work-up by dilution with water and extraction

- Remove electrolyte by passing through short silica plug

Advantages: Eliminates stoichiometric oxidants, mild conditions, tunable by potential

Strategic Workflow for Method Development

This systematic approach enables efficient development of C–H activation methodologies for complex natural product synthesis. By addressing common experimental challenges through targeted troubleshooting and strategic reagent selection, researchers can effectively implement these transformative methods to overcome synthetic intractability in their synthetic campaigns.

The development of therapeutics from Natural Active Products (NAPs) is often hampered by the challenge of synthetic intractability. Many NAPs possess complex chemical structures that make derivative synthesis for labeled approaches—such as attaching biotin or fluorescent tags—a time-consuming process that risks altering their native biological activity [29] [30]. Label-free target identification methods have emerged as powerful tools to overcome this hurdle. These techniques do not require chemical modification of the small molecule, thereby preserving its natural structure and function, and directly identify protein targets by detecting the biophysical consequences of ligand-binding events [31] [29]. This technical support center details the application, troubleshooting, and protocols for four key label-free methods: DARTS, CETSA, LiP-MS, and SPROX, providing a critical toolkit for advancing NAP drug discovery.

Methodologies at a Glance: Principles and Applications

The table below summarizes the core principles, standard sample types, and primary applications of these four key methodologies to help you select the appropriate technique.

| Method | Core Principle | Common Sample Types | Typical Readout | Main Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DARTS [29] [32] | Ligand binding protects the target protein from proteolysis. | Cell lysates, purified proteins [32] | SDS-PAGE/Western Blot, Mass Spectrometry [32] | Initial target validation and identification [32] |

| CETSA [31] [32] | Ligand binding increases the thermal stability of the target protein, raising its melting temperature ((T_m)). | Live cells, cell lysates [32] | Western Blot, Mass Spectrometry (CETSA-MS) [32] | Target engagement in a near-physiological context [32] |

| LiP-MS [31] | Ligand binding alters the protein's susceptibility to proteolysis, changing the peptide digestion profile. | Cell lysates, complex protein mixtures | Mass Spectrometry (Peptide mapping) | Proteome-wide target and binding site identification [31] |

| SPROX [31] [29] | Ligand binding increases the protein's resistance to chemical denaturation and oxidation. | Cell lysates, complex protein mixtures | Mass Spectrometry | Proteome-wide target identification based on thermodynamic stability [31] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)

Q: Our CETSA western blot data shows high background and nonspecific protein aggregation. What steps can we take to optimize this?

- A: This is often due to suboptimal heating conditions or lysis.

- Optimize Temperature Gradient: Run a wide temperature range (e.g., 37°C to 67°C) on control samples to establish a precise melting curve ((Tm)) for your target protein. The most informative data comes from temperatures around the (Tm) [32].

- Validate Detection Antibody: Ensure your antibody is specific and suitable for detecting the denatured protein in the soluble fraction after heat shock and centrifugation [32].

- Use Appropriate Controls: Always include a vehicle (e.g., DMSO) control and, if available, a well-characterized ligand as a positive control to confirm a observable thermal shift [32].

Q: When should we use live cells versus cell lysates for CETSA?

- A: The choice depends on your research question.

- Use Live Cells: To confirm that your compound penetrates the cell membrane and engages the target in a physiologically relevant environment, including intact cellular structures and protein complexes [32].

- Use Cell Lysates: To study direct binding without the confounding effects of cellular uptake, efflux, or metabolism. This can also simplify the system for initial method optimization [32].

Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS)

Q: We are unable to see a clear protective effect in our DARTS experiment. What is the most critical parameter to optimize?

- A: Protease concentration is the most crucial and often problematic parameter.

- Titrate the Protease: A single, fixed concentration rarely works. You must perform a protease titration (e.g., of pronase or thermolysin) with your vehicle-treated sample to find the concentration that digests ~50-80% of the target protein. The protective effect of the ligand is most apparent at this "window" of digestion [32].

- Consider Protein Conformation: DARTS is most effective for ligands that induce a significant conformational change in the target protein, shielding protease cleavage sites. If the binding does not alter the protease-accessible regions, the signal will be weak [32].

Q: Can DARTS be used for proteome-wide screening?

- A: Yes, by coupling it with mass spectrometry (DARTS-MS). While traditional DARTS uses western blotting to monitor one or a few proteins, DARTS-MS uses a label-free quantitative proteomics workflow to compare the peptide abundances between compound-treated and vehicle-treated samples after proteolysis. This allows for the unbiased identification of potential target proteins across the proteome [29] [32].

Limited Proteolysis coupled with Mass Spectrometry (LiP-MS) & Stability of Proteins from Rates of Oxidation (SPROX)

Q: What is the key difference between LiP-MS and SPROX in what they detect?

- A: Both use mass spectrometry but monitor different biophysical consequences of ligand binding.

- LiP-MS detects ligand-induced changes in a protein's structural flexibility and solvent accessibility, which alters the pattern of peptides generated by a nonspecific protease [31].

- SPROX detects ligand-induced changes in a protein's thermodynamic stability against chemical denaturation, measured by its resistance to methionine oxidation under increasing denaturant concentrations [31] [29].

Q: Our LiP-MS/SPROX experiment yielded a long list of candidate hits. How can we prioritize targets for validation?

- A: This is a common challenge in untargeted proteomics.

- Stringent Statistics: Apply strict false discovery rate (FDR) correction (e.g., (q < 0.05)) and require a significant fold-change.

- Dose-Dependency: Treat samples with a range of compound concentrations. True targets often show a dose-dependent stabilization effect.

- Bioinformatic Integration: Cross-reference your hit list with gene ontology (GO) enrichment and pathway analysis (KEGG, Reactome) to see if the proteins cluster in a biologically relevant pathway for your compound's known phenotype.

- Orthogonal Validation: Always confirm top hits using an orthogonal method, such as CETSA, DARTS, or a functional biochemical assay [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

CETSA Protocol (Using Cell Lysates)

This protocol assesses target engagement in a simplified, cell-free system [32].

Workflow Diagram: CETSA in Cell Lysates

Step-by-Step Guide:

- Lysate Preparation: Lyse cultured cells in a non-denaturing PBS-based buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Clear the lysate by high-speed centrifugation (>15,000 x g).

- Compound Incubation: Divide the lysate into two portions. Incubate one with your NAP (dissolved in DMSO) and the other with vehicle-only (DMSO) as a control for 30-60 minutes on ice.

- Heat Denaturation: Aliquot each sample (compound and vehicle) into thin-wall PCR tubes and heat them individually across a defined temperature gradient (e.g., from 37°C to 67°C) for 3 minutes.

- Protein Aggregation and Separation: Immediately cool all tubes on ice. Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 20,000 x g) at 4°C to separate the soluble (folded) protein from the insoluble (aggregated) pellet.

- Analysis: Analyze the soluble fractions by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using an antibody against your protein of interest.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the band intensity. Plot the remaining soluble protein (%) versus temperature to generate a melting curve. A rightward shift ((T_m) increase) in the compound-treated sample indicates stabilization and binding.

DARTS Protocol

This protocol is based on the principle of ligand-induced protection from proteolysis [32].

Workflow Diagram: DARTS

Step-by-Step Guide:

- Lysate Preparation: Prepare a cell lysate as described in the CETSA protocol.

- Compound Binding: Divide the lysate and incubate with NAP or vehicle control.

- Proteolysis (Critical Step): In a separate pre-cooled tube, incubate the lysate mixtures with a titrated amount of pronase or thermolysin for a limited time (e.g., 10-30 minutes on ice). A preliminary protease titration is essential.

- Reaction Stop: Stop the proteolysis by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer and heating.

- Analysis: Analyze the samples by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

- Data Analysis: Compare the band intensity of the protein of interest between the compound-treated and vehicle-treated samples. A stronger band in the compound-treated sample indicates protection from proteolysis due to binding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their critical functions for successfully implementing these label-free methods.

| Reagent / Material | Function & Importance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lysate | Source of native protein targets for DARTS, LiP-MS, SPROX, and lysate-based CETSA. | Use non-denaturing lysis buffers. Pre-clear by centrifugation. Protein concentration should be consistent across samples. |

| Live Cells | Essential for physiologically relevant CETSA to study target engagement in a cellular context. | Ensure high cell viability. Consider compound solubility and potential cytotoxicity during incubation. |

| Pronase/Thermolysin | Non-specific proteases for DARTS and LiP-MS. | Requires extensive titration. Source and lot-to-lot variability can be high; optimize for each new batch. |

| Chemical Denaturants (e.g., GuHCl) | Used in SPROX to unfold proteins and expose methionine residues to oxidation. | Prepare fresh, high-purity stock solutions. Accurately prepare the concentration gradient. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Core instrument for DARTS-MS, CETSA-MS, LiP-MS, and SPROX for proteome-wide, unbiased target discovery. | Requires expertise in liquid chromatography (LC) and tandem MS (MS/MS) operation and data analysis. |

| High-Quality Antibodies | For specific detection of target proteins in Western blot-based CETSA and DARTS. | Validate specificity and sensitivity for the target protein. Must work well for denatured protein (CETSA). |

| Methionine Oxidation Reagent | Hydrogen peroxide ((H2O2)) is typically used in SPROX to oxidize methionine residues in unfolded regions. | Reaction time and concentration must be carefully controlled to achieve limited oxidation. |

Method Selection and Workflow Diagram

Choosing the right method depends on your experimental goals, resources, and the biological context. The following diagram outlines a decision pathway to guide your selection.

Integrating Computational Design and High-Throughput Crystallography in the FBDD Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary advantages of integrating computational design with high-throughput crystallography in FBDD?

Integrating computational design with high-throughput crystallography creates a powerful synergy in Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD). Computational methods, including fragment informatics, high-throughput docking, and de novo design, significantly improve the efficiency and success rate of lead discovery and optimization [22]. They can be used independently or in parallel with experimental FBDD. When a high-resolution crystal system is available (typically diffracting to <2.5 Å), high-throughput crystallography provides unambiguous confirmation of fragment binding and generates detailed information about the protein-fragment interaction within the 3D protein structure [33]. This structural data directly feeds back into and refines the computational models, creating a virtuous cycle of design and experimental validation.

FAQ 2: Our fragment hits have poor electron density maps, making binding modes hard to interpret. How can we resolve this?

This is a common challenge when detecting weak binders. The PanDDA (Pan Dataset Density Analysis) algorithm is specifically designed to overcome this. It helps amplify the signal of weak fragment binders in electron density maps that would be difficult to interpret using conventional methods [33]. Furthermore, ensuring your experimental setup meets key requirements is crucial: a high-resolution crystal system (diffracting to <2.5 Å), robust crystals that can tolerate at least 10-30% DMSO for soaking, and crystal form uniformity, which is essential for PanDDA analysis [33].

FAQ 3: Why is synthetic intractability a major bottleneck in FBDD, and what are the emerging solutions?