Overcoming Complexity: Modern Strategies for the Synthesis of Natural Products

This article addresses the significant challenge of structural complexity in natural product synthesis, a central field for drug discovery.

Overcoming Complexity: Modern Strategies for the Synthesis of Natural Products

Abstract

This article addresses the significant challenge of structural complexity in natural product synthesis, a central field for drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational reasons behind synthetic complexity and details cutting-edge strategies to overcome it. The scope encompasses traditional total synthesis, innovative simplification approaches, the rise of computational and bioinspired planning, and the critical validation of these methods through case studies and comparative analysis. By synthesizing insights from these four core intents, the article provides a comprehensive roadmap for developing complex natural products and their optimized derivatives into viable clinical candidates.

The Intricate Architecture of Natural Products: Defining the Challenge

What Makes a Natural Product 'Complex'? An Analysis of Molecular Scaffolds

FAQs: Understanding and Analyzing Structural Complexity

Q1: What molecular features primarily contribute to the structural complexity of a natural product?

Structural complexity in natural products arises from a combination of several key molecular features:

- High Scaffold Diversity: The presence of unique and varied carbon skeletons or core structures, as opposed to simple, flat scaffolds. Strategies like Complexity-to-Diversity (CtD) use complex natural product starting materials to generate libraries of compounds each based on a distinct molecular scaffold [1].

- Significant Stereochemical Complexity: The presence of multiple stereocenters (chiral centers), particularly those with defined and challenging relative configurations. This includes complex ring systems with distal stereocenters interrupted by rigid substructures [2].

- Macrocyclic and Medium-Sized Rings: Macrocycles are large-ring compounds (often 12+ atoms) that are conformationally restrained but can exhibit diverse biological properties. Medium-sized rings (7-11 membered) are also particularly challenging due to unfavorable transannular interactions and entropic effects, making them synthetically difficult and under-represented in screening libraries [3].

- Functionalization and Substituents: A high density of diverse functional groups installed via methods like C–H functionalization, which can further be used for ring expansion reactions to access novel chemical space [3].

Q2: What are the main experimental challenges in determining the structure of a complex natural product?

The primary challenges include:

- Structural Elucidation of Minor Components: Often, the most interesting compounds are available in only minute quantities (micrograms or nanomoles), pushing the limits of analytical techniques like NMR [4].

- Assignment of Stereochemistry: Determining the relative and absolute configuration of multiple stereocenters, especially when they are distal (far apart in the molecule) or separated by rotatable bonds, is notoriously difficult. NMR alone can be insufficient for this task [2] [5].

- Crystallization for X-ray Analysis: X-ray crystallography is the gold standard for unambiguous structure determination but is often thwarted by an inability to grow crystals of sufficient size and quality from the available material [2].

- Misassignment from Spectroscopic Data: Structural proposals can be erroneous due to biases in interpreting complex NMR data, leading to published structures that require subsequent revision [5].

Q3: What advanced techniques are available for the structural elucidation of complex natural products when material is scarce?

Modern techniques have dramatically lowered the required amount of material for full structure elucidation:

- Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED): An emerging cryo-electron microscopy (CryoEM) method that provides unambiguous atomic-level structures from sub-micron-sized crystals, which are too small for conventional X-ray diffraction. This technique has been pivotal in solving and even revising the structures of complex natural products [2].

- Microcryoprobe NMR: NMR probes with cryogenically cooled electronics that use small-volume capillaries (1-1.7 mm). This technology increases the signal-to-noise ratio by 10-20 fold, allowing the acquisition of multi-dimensional NMR data on nanomole-scale samples (a few micrograms for a 1000 Da compound) [4].

- Computational NMR Prediction: Using density functional theory (DFT) and other computational methods to predict NMR chemical shifts and spin-spin coupling constants. Comparing these calculated spectra with experimental data is a powerful method for validating proposed structures and identifying errors [5].

- Circular Dichroism (CD): A highly sensitive chiroptical technique that, when combined with computational predictions (time-dependent DFT), can assign absolute configuration at the picomole level, complementing NMR data [4].

Q4: What strategies exist to diversify complex natural products and access novel chemical space for drug discovery?

Two prominent synthetic strategies are:

- Complexity-to-Diversity (CtD): This approach exploits the inherent structural and stereochemical complexity of a natural product as a starting point. The natural product-derived intermediate is divergently functionalized and then transformed (e.g., via macrocyclization) to generate novel, structurally diverse, and complex compounds that share the core complexity but explore new scaffolds [1].

- C–H Functionalization / Ring Expansion: This strategy first installs new functional groups at specific C-H bonds—which are ubiquitous in natural products—using selective methods like electrochemical oxidation. These new functional groups then serve as handles for ring expansion reactions, converting common small rings (e.g., in steroids) into rare and challenging medium-sized rings, thereby accessing underexplored chemical space [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inability to Determine Relative Stereochemistry of Distal Stereocenters

Problem: NMR data is insufficient to determine the relative stereochemistry between stereocenters located far apart in a complex natural product, especially when linked through rotatable bonds.

Solution:

- Employ MicroED Analysis: If the compound can be induced to form microcrystals, MicroED can provide a definitive 3D structure, including all relative configurations, without the need for large single crystals. This method was successfully used to unambiguously establish the stereochemistry of Py-469, a new natural product where NMR was inconclusive [2].

- Utilize Computational CD Spectroscopy: Compare the experimental circular dichroism spectrum with spectra calculated via time-dependent DFT for different proposed stereoisomers. A match can confirm the correct absolute configuration [4].

- Engage in Total Synthesis or Degradation: If spectroscopic methods fail, a targeted synthesis of the proposed stereoisomer or chemical degradation to a fragment of known configuration can provide conclusive proof [4] [5].

Issue: Low Abundance of a Novel Compound in a Complex Extract

Problem: A promising novel natural product is present in very low abundance in a complex biological matrix, making isolation and purification inefficient.

Solution:

- Prioritize with Metabolite Profiling: Use advanced UHPLC-HRMS to create a detailed metabolic profile of the extract. This allows for the dereplication (early identification of known compounds) and annotation of novel or unusual compounds before committing to isolation [6].

- Implement High-Resolution Chromatographic Strategies:

- Use online two-dimensional (2D) chromatography systems for higher peak capacity and separation power.

- Employ trap columns for the repetitive enrichment and purification of low-abundance targets from multiple analytical-scale injections, automating the process and reducing intermediate contamination [7].

- Transfer optimized analytical UHPLC conditions directly to the semi-preparative scale using chromatographic modelling software to maintain high resolution and efficiency during upscaling [6].

- Hyphenate Detection for Precision: Use semi-preparative HPLC coupled with multiple detectors (UV, MS, ELSD) to precisely trigger the collection of the target peak based on its specific retention time and mass, ensuring purity [6].

Quantitative Data on Molecular Complexity

Table 1: Key Metrics of Structural Complexity in Selected Natural Product Classes

| Natural Product / Class | Molecular Weight Range | Number of Stereocenters | Ring System (Size & Type) | Key Complexity Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phorboxazoles (e.g., 1 & 2) [4] | ~700-1400 Da | Multiple | Macrocycles, Oxazoles | Potent bioactivity at sub-nanomolar levels; complex stereochemistry [4]. |

| Steroid-Derived Medium-Sized Rings [3] | Modified from core steroids | Defined by parent + new centers | 7-11 membered rings fused to polycyclic systems | Expansion of common scaffolds into underexplored medium-ring chemical space [3]. |

| Macrocycles from Quinine [1] | N/A | Inherited from Quinine + new | Macrocycles (exact size N/A) | High scaffold diversity from a single, complex natural product starting material [1]. |

| Py-469 [2] | 469 Da | Multiple, including distal centers | Decalin, 2-pyridone, epoxydiol | Challenging stereochemical assignment of a distal epoxydiol system [2]. |

Table 2: Scale and Sensitivity of Modern Structure Elucidation Techniques

| Technique | Typical Sample Requirement | Key Structural Information Provided | Primary Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|---|

| MicroED [2] | Sub-micron crystals | Full 3D atomic structure (relative configuration) | Definitive stereochemistry when NMR is ambiguous or crystals are too small for SC-XRD [2]. |

| Microcryoprobe NMR [4] | Nanomole (e.g., ~5-20 μg) | Atom connectivity, relative configuration (via NOE, J-couplings) | Acquiring full suite of 1D/2D NMR spectra on vanishingly small samples [4]. |

| Computational NMR Prediction [5] | N/A (in silico) | Predicted ( ^1H ) and ( ^{13}C ) chemical shifts & coupling constants | Validating proposed structures and identifying misassignments by comparing calculated vs. experimental data [5]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) [4] | Picomole | Absolute configuration | Assigning stereochemistry when sample amounts are too low for other techniques [4]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Structure Elucidation of a Microgram-Quantity Natural Product Using MicroED

Purpose: To determine the atomic structure and stereochemistry of a novel natural product available only in microgram quantities.

Background: Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED) has revolutionized structure elucidation by allowing analysis from nano-crystalline material that is unsuitable for traditional single-crystal X-ray diffraction [2].

Materials:

- Purified natural product (as little as 1 mg/L culture in a proof-of-concept study [2])

- Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) equipped with a cryo-holder and capable of electron diffraction

- Standard cryo-EM grid preparation supplies

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: a. Purify the target compound to homogeneity using HPLC [2]. b. Lyophilize the purified sample to a powder. c. Gently grind the powder and disperse it onto a cryo-EM grid.

- Screening and Data Collection: a. Load the grid into the TEM under cryogenic conditions. b. Screen the sample at low magnification to identify crystalline domains. c. Center a suitable crystal and collect a diffraction movie while continuously rotating the stage. Note: In the case of Py-469, merging data from just two movies yielded a high-resolution (0.85 Å) structure [2].

- Data Processing and Structure Determination: a. Process the diffraction movies using standard crystallographic software (e.g., XDS, SHELX) to generate a merged intensity data file. b. Solve the structure by direct methods or intrinsic phasing. c. Refine the structure anisotropically to convergence. The structure of Py-469 was refined to an R1 value of 13.8% [2].

Protocol: Diversification of Natural Products via C–H Oxidation and Ring Expansion

Purpose: To diversify polycyclic natural products (e.g., steroids) and generate novel analogues containing medium-sized rings.

Background: This two-phase strategy first installs functional groups via selective C–H bond oxidation, then uses these groups to drive ring expansion reactions, accessing synthetically challenging medium-sized rings [3].

Materials:

- Natural product starting material (e.g., DHEA, cholesterol, estrone)

- Reagents for C–H oxidation (e.g., electrochemical cell, catalysts like Cu or Cr complexes)

- Ring expansion reagents (e.g., ethyl diazoacetate, BF₃•Et₂O, dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate (DMAD))

- Standard anhydrous solvents and inert atmosphere equipment

Procedure:

- Site-Selective C–H Oxidation: a. Set up the reaction according to the chosen oxidation method. For example, use a published electrochemical protocol for allylic C–H oxidation [3] or a copper-mediated system for other positions. b. Monitor the reaction by TLC or LC-MS. c. Upon completion, isolate and purify the oxidized intermediate (e.g., ketone 28 from benzylic oxidation of 1j) [3].

- Ring Expansion: a. Subject the oxidized intermediate to a ring expansion reaction. Multiple pathways are possible: - Schmidt Reaction: React a ketone with hydrazoic acid to form a lactam, expanding the ring by one carbon [3]. - Formal [2+2] Cycloaddition/Fragmentation: React a β-keto ester (e.g., 2a) with DMAD to effect a two-carbon ring expansion, ultimately yielding an anhydride (e.g., 6a) [3]. - Beckmann Rearrangement: Treat a ketoxime derived from the oxidized product to form a lactam [3]. b. Purify the final ring-expanded product(s) using techniques like flash chromatography or preparative HPLC.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Complex Natural Product Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Trap Columns (for HPLC) | Online enrichment and purification of low-abundance compounds from complex extracts [7]. | Used in an online prep-HPLC system for the efficient separation of Panax notoginseng saponins [7]. |

| C–H Oxidation Catalysts | Selective functionalization of inert C-H bonds to introduce handles for further diversification [3]. | Electrochemical, Copper-mediated, and Chromium-mediated catalysts used to oxidize specific positions on steroid cores [3]. |

| Ring Expansion Reagents | Transformation of small rings into synthetically challenging medium-sized rings (7-11 members) [3]. | Ethyl diazoacetate, Dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate (DMAD), and reagents for the Schmidt reaction and Beckmann rearrangement [3]. |

| Cryogenic NMR Solvents | For acquiring high-sensitivity NMR data on microgram-scale samples using microcryoprobes. | Essential for protocols requiring nanomole-level structure elucidation [4]. |

| MicroED Grids | Support for nano-crystalline samples during data collection in the transmission electron microscope. | Used for the ab initio structural elucidation of Py-469 and revision of fischerin [2]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

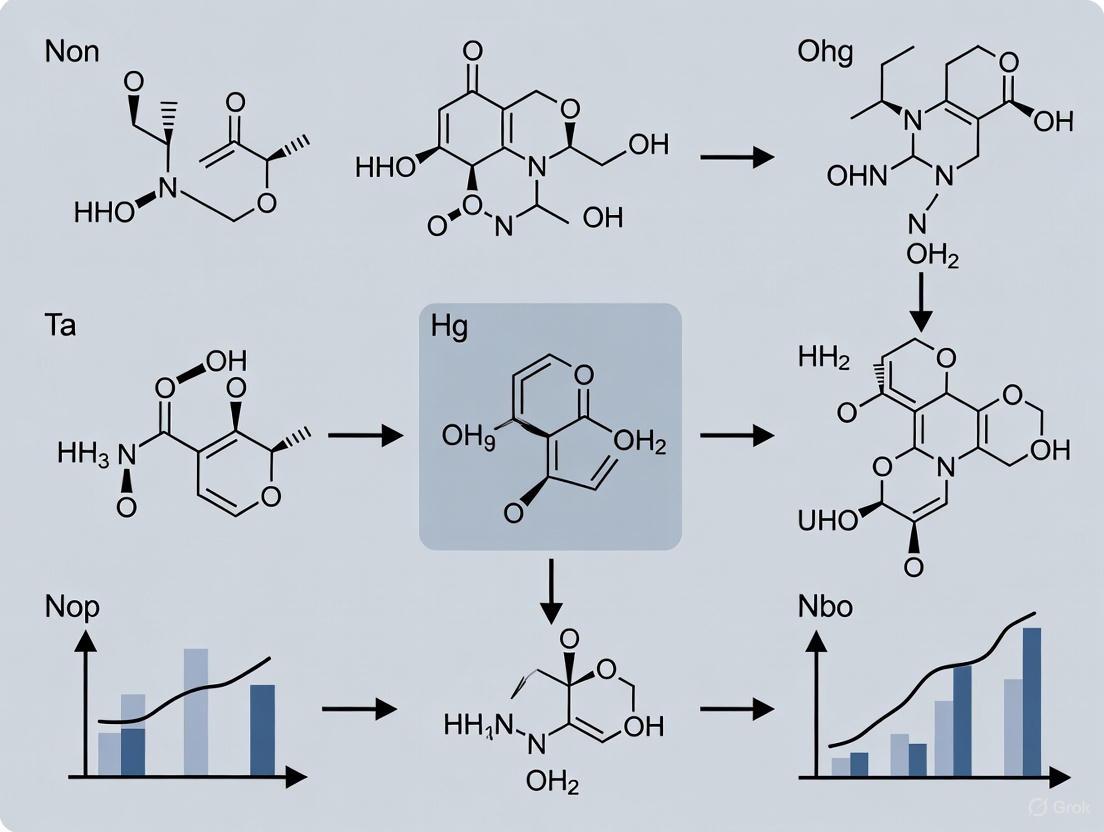

Diagram Title: Workflow for Analyzing and Diversifying Complex Natural Products

Diagram Title: Synthetic Strategies for Diversifying Complex Natural Products

Natural products, chemicals produced by living organisms, are a treasure trove for developing bioactive molecules and pharmaceuticals; more than 60% of pharmaceuticals are related to natural products [2]. However, their structural complexity often makes synthesis a daunting task. The rate-limiting step in natural product discovery is frequently structural characterization, which, if misassigned, can lead researchers down unproductive synthetic paths [8] [2]. This technical support center is designed within the context of a broader thesis on addressing structural complexity in natural product research. It provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you overcome common experimental hurdles, confirm structures efficiently, and apply innovative synthetic methodologies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is total synthesis considered a reliable tool for structural confirmation? Even with substantial improvements in spectroscopic techniques, the structural misassignment of natural products remains common. Total synthesis serves as an unambiguous method for structural confirmation by independently recreating the proposed structure. When the physical and spectral data (NMR, MS, etc.) of the synthesized material match those of the isolated natural product, the structure is confirmed. This process has led to the revision of numerous previously misassigned structures [8].

2. What are the common challenges in the structural elucidation of natural products? Difficulties often arise from:

- Limited Material: Lack of sufficient quantities for traditional methods like NMR or X-ray crystallography [2].

- Poor Physical Properties: Issues such as poor solubility or stability in standard NMR solvents [2].

- Limitations of NMR: Challenges in determining relative stereochemistry, especially in molecules with distal stereocenters interrupted by rigid substructures [2].

3. What is protecting-group-free (PGF) synthesis and why is it beneficial? PGF synthesis is an approach that aims to construct complex natural products without using protecting groups. This is achieved through highly chemoselective reactions that preferentially react with one functional group in the presence of others. The key benefits are dramatically improved efficiency and step economy, as it avoids the additional steps of protection and deprotection [9].

4. What is Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED) and how does it aid structure determination? MicroED is an emerging cryogenic electron microscopy (CryoEM) method used for unambiguous structural elucidation, including stereochemistry. It can determine structures from sub-micron-sized crystals that are too small for traditional single-crystal X-ray diffraction. This technology has been used to both determine new natural product structures and revise the structures of compounds isolated decades ago [2].

5. When is retrosynthetic analysis particularly useful? Retrosynthetic analysis is a fundamental strategy for planning the synthesis of complex molecules. It involves working backward from the target molecule, deconstructing it into simpler, readily available starting materials through a series of disconnections. This provides a structured, logical approach to tackling complex syntheses [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Structural Misassignment

This guide addresses the common problem of ambiguous or incorrect structural determination.

- Problem: Cannot unambiguously assign relative stereochemistry, especially of distal stereocenters, using NMR data alone.

- Context: The molecule contains rigid substructures with multiple rotatable bonds, preventing definitive NOE analysis [2].

Solution: Apply a Multi-Technique Verification Approach

| Step | Action | Principle & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Re-evaluate with Advanced NMR | Attempt to resolve ambiguities by collecting additional data (e.g., 2D NMR) or using computational NMR prediction to compare proposed models [2]. |

| 2 | Pursue MicroED Analysis | If the compound or a derivative can be coaxed to form microcrystals, use MicroED for ab initio structural determination. This is now a viable alternative when X-ray quality crystals cannot be obtained [2]. |

| 3 | Design a Total Synthesis | Undertake the total synthesis of the proposed structure. A successful synthesis that produces a compound with identical data to the natural product provides the highest level of confirmation [8]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Low-Yielding or Inefficient Syntheses

This guide helps when a synthetic route is too long, inefficient, or plagued by low yields.

- Problem: Synthetic route requires too many steps, including multiple protection/deprotection sequences, leading to low overall yield.

- Context: The target molecule has multiple similar functional groups that interfere with desired reactions [9].

Solution: Implement Protecting-Group-Free (PGF) and Chemoselective Strategies

| Step | Action | Principle & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Conduct a Retrosynthetic Analysis | Deconstruct the target with a focus on late-stage introduction of reactive functional groups and isohypsic transformations (where the oxidation state remains unchanged) [9]. |

| 2 | Prioritize Chemoselective Methods | Research and employ modern chemoselective catalysts and reactions that can distinguish between functional groups without the need for protection [9]. |

| 3 | Utilize Tandem Reaction Cascades | Design strategies that use cascade or one-pot reactions to build complex carbon skeletons efficiently and functional-group-tolerant cyclizations [9]. |

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Failed Reproducibility of a Literature Synthesis

This guide assists when an experimental protocol from published literature fails to produce the expected results in your lab.

- Problem: Following a published synthetic procedure does not yield the expected product.

- Context: The reaction setup, reagents, or techniques may have subtle but critical differences.

Solution: Systematic Hypothesis Testing

| Step | Action | Principle & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify "What Touched It Last" | Scrutinize all recent changes. Check the purity and source of all starting materials and reagents. Ensure catalysts or sensitive reagents are fresh and have been stored correctly [11]. |

| 2 | Simplify and Reduce | Reproduce the reaction on a smaller scale, systematically testing each variable (e.g., solvent quality, temperature control, water/oxygen sensitivity) to isolate the cause of failure [11]. |

| 3 | Ask "What, Where, and Why" | Analyze what is actually happening in your reaction. Use TLC, LC-MS, or NMR to identify side products or unreacted starting material. This evidence can point to the underlying issue [11]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Comparison of Structural Elucidation Techniques

The following table summarizes key techniques for tackling structural complexity, helping you choose the right tool for your research challenge.

| Technique | Principle | Key Application in Natural Products | Typical Data Output | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy | Analyzes magnetic properties of nuclei in a molecule. | Determination of planar structure and relative configuration. | Chemical shifts, coupling constants, 2D correlation maps. | Provides abundant information on connectivity and environment. | Can be ambiguous for stereochemistry and requires pure sample [2]. |

| X-ray Crystallography | Scatters X-rays off a crystalline sample to determine electron density. | Unambiguous determination of full structure, including absolute stereochemistry. | Atomic coordinates, crystal structure. | Considered the "gold-standard" for unambiguous structure proof. | Requires large, high-quality single crystals [2]. |

| MicroED | Scatters electrons off nano-crystals to determine structure. | Full structural determination when X-ray quality crystals cannot be obtained. | Atomic coordinates, crystal structure. | Works with nano-crystals; rapid data collection. | Requires sample to form ordered microcrystals [2]. |

| Total Synthesis | De novo chemical synthesis of the target molecule. | Ultimate confirmation of a proposed structure through independent creation. | Synthesized compound for direct comparison. | Provides definitive proof and can supply scarce natural products. | Time-consuming and requires significant synthetic expertise [8]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table details key reagents and their roles in modern natural product synthesis and analysis.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Context of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Chemoselective Catalysts | Catalysts (e.g., Au, Pd complexes) designed to react with one specific functional group in the presence of others. | Enables protecting-group-free synthesis by selectively transforming a single site on a complex molecule [9]. |

| Umpolung Reagents | Reagents that temporarily reverse the innate polarity of a functional group (e.g., dithioacetals for acyl anion equivalents). | Allows for disconnection strategies that would otherwise be impossible, enabling novel bond formations [10]. |

| Genetically Engineered Hosts (e.g., A. nidulans) | Heterologous biosynthetic hosts refactored with specific gene clusters to produce target natural products or analogs. | Used in genome mining and synthetic biology to produce novel metabolites or rediscover compounds no longer available [2]. |

Workflow and Methodology Diagrams

Diagram 1: Structural Confirmation Workflow

Diagram 2: Systematic Troubleshooting Methodology

FAQs: Navigating Bioactivity and Synthesis

FAQ 1: What is the most common reason for the failure of clinical drug development? Recent analyses indicate that approximately 90% of clinical drug development fails. A predominant reason is that the optimization process overly focuses on a candidate's potency and specificity (Structure-Activity Relationship, or SAR) while overlooking a critical factor: its tissue exposure and selectivity (Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity-Relationship, or STR). An imbalance here can mislead candidate selection and negatively impact the clinical balance between dose, efficacy, and toxicity [12].

FAQ 2: How can we improve the drug optimization process to increase the chance of clinical success? A proposed solution is the Structure–Tissue exposure/selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) framework. This approach classifies drug candidates based on a holistic view of their properties, ensuring that both potency and tissue distribution are considered to select compounds with a better predictive balance of efficacy and safety [12]. Furthermore, in 2025, the industry is seeing a significant shift towards prioritizing high-quality, real-world patient data for training AI models in drug discovery, moving away from an over-reliance on synthetic data, to create more reliable and clinically validated processes [13].

FAQ 3: What role do biomarkers play in modern drug development, especially in complex fields like psychiatry? Biomarkers serve as scientifically valid, objective data points that can be measured and tested. In psychiatric drug development, they are particularly crucial for supporting the development of new treatments. Among the most promising are event-related potentials, which are functional brain measures noted for their high reliability, consistency, and interpretability in numerous studies. A broader application of such biomarkers is expected in clinical trials [13].

FAQ 4: What are the key trends in clinical trial design for improving efficiency? Two major trends are shaping clinical trials:

- AI-Driven Optimization: The use of AI is becoming transformative, with over half of new trials expected to incorporate AI for protocol optimization. This enhances site selection, patient recruitment, and enables precision-driven protocols by using predictive analytics on data like genomics and clinical records [13].

- Hybrid Trials: Hybrid trial models are becoming the standard, especially for chronic diseases. These models combine traditional site-based visits with decentralized tools, making participation easier for patients and incorporating real-world data to adapt designs based on day-to-day patient experiences [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Hurdles

This guide addresses frequent challenges in balancing bioactivity and synthesis.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Optimization | A compound shows high in vitro potency but poor efficacy or high toxicity in vivo. | Poor tissue exposure/selectivity; the compound may not reach the diseased tissue effectively or may accumulate in healthy tissues [12]. | Implement the STAR framework for candidate selection. Prioritize compounds with high tissue exposure/selectivity (Class I and III) over those with only high potency but poor tissue profiles (Class II) [12]. |

| Clinical Trial Enrollment | Slow patient recruitment and enrollment delays trial timelines. | Inefficient site selection and difficulty identifying eligible patients from unstructured clinical notes [13]. | Adopt AI-driven predictive analytics to optimize site selection and patient recruitment. Utilize AI tools with natural language processing to abstract data from unstructured clinical notes and EHRs [13]. |

| Data for AI Models | AI models trained for drug discovery yield unreliable or non-generalizable results. | Over-reliance on synthetic data for training, which may not fully capture real-world clinical complexity [13]. | Prioritize high-quality, real-world patient data for AI model training. Use synthetic data primarily for refining trial design and early-stage analysis, not as a complete replacement [13]. |

| Analytical Instrumentation (GC System) | Gradual increase in peak retention times or a noisy/spiky baseline. | Column contamination from matrix buildup or ambient pressure fluctuations affecting the Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) [14]. | For retention shifts: Perform column maintenance (e.g., baking out or solvent rinsing). For TCD noise: Install a small restrictor on the detector exit to isolate it from lab pressure changes [14]. |

Quantitative Data in Drug Development

Table 1: The STAR Drug Classification Framework for Candidate Selection This framework, derived from recent research, helps balance key properties to improve clinical success rates [12].

| STAR Class | Specificity / Potency | Tissue Exposure / Selectivity | Required Dose | Expected Clinical Outcome & Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Low | Superior efficacy/safety; High success rate |

| Class II | High | Low | High | Efficacy with high toxicity; Needs cautious evaluation |

| Class III | Adequate / Low | High | Low | Efficacy with manageable toxicity; Often overlooked |

| Class IV | Low | Low | N/A | Inadequate efficacy/safety; Terminate early |

Table 2: Key Predictions for Drug Development in 2025 Industry experts forecast several key trends for the near future [13].

| Area of Development | Predicted Trend in 2025 | Key Driver or Enabling Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Data for AI Training | Pullback from synthetic data; precedence of real-world data. | Recognition of synthetic data's limitations and potential risks. |

| Clinical Trial Design | >50% of new trials use AI-driven protocol optimization. | Predictive analytics, AI for patient recruitment & site selection. |

| Trial Data Management | Scaling of clinical data abstraction. | AI-based tools with human experts "in the loop" to extract data from unstructured clinical notes. |

| Trial Execution Model | Hybrid trials become the standard. | Tools like NLP for patient engagement; decentralized models for chronic disease. |

| Psychiatric Drug Development | Breakthrough in biomarker validation & consensus. | Adoption of reliable, consistent biomarkers like event-related potentials. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the STAR Framework in Lead Optimization

Objective: To systematically evaluate and classify drug candidates based on the Structure–Tissue exposure/selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) to select the most promising lead with a balanced efficacy/toxicity profile.

Methodology:

- In Vitro Potency & Specificity Assay (SAR):

- Determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) or similar potency metrics against the primary target.

- Evaluate selectivity by profiling the compound against a panel of related off-targets (e.g., kinases, GPCRs) to establish specificity.

- Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Profiling (STR):

- Administer a single, pharmacologically relevant dose of the candidate compound to animal models.

- At predetermined time points, collect plasma and homogenize key target tissues (e.g., tumor, liver, brain) and potential toxicity-related tissues (e.g., heart, kidney).

- Use LC-MS/MS to quantify the compound's concentration in each tissue matrix. Calculate the tissue-to-plasma ratio and the specific exposure in the diseased tissue versus healthy tissues.

- STAR Integration and Classification:

- Integrate the data from steps 1 and 2. Plot candidates on a matrix with "Potency/Specificity" on one axis and "Tissue Exposure/Selectivity" on the other.

- Classify each candidate into one of the four STAR classes (I-IV) as defined in Table 1.

- Selection Priority: Prioritize Class I and Class III candidates for further development, deeply scrutinize Class II, and terminate Class IV candidates [12].

Protocol 2: AI-Enhanced Clinical Data Abstraction for Trial Acceleration

Objective: To harness AI-powered tools to efficiently structure unstructured clinical notes from Electronic Health Records (EHRs) for faster patient cohort identification and clinical trial enrollment.

Methodology:

- Tool Selection and Setup:

- Identify and implement an AI-based clinical data abstraction platform that supports a "human-in-the-loop" model, ensuring accuracy and clinical relevance [13].

- Data Ingestion and Pre-processing:

- Securely import de-identified EHR data, including free-text clinical notes, pathology reports, and discharge summaries, into the abstraction platform.

- AI-Driven Natural Language Processing (NLP):

- The NLP engine processes the unstructured text to identify and extract key entities and concepts relevant to the trial's inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g., specific diagnoses, medication history, lab values, procedural history).

- Clinical Expert Validation (Human-in-the-Loop):

- A clinical expert reviews the AI-extracted data points for accuracy and context, correcting any misclassifications. This step continuously trains and improves the AI model.

- Structured Data Output and Patient Matching:

- The validated output is converted into a structured database. This database is then used to run queries against the trial's protocol to pre-identify a list of potentially eligible patients, drastically speeding up the recruitment process [13].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS System | The core analytical platform for quantifying drug candidate concentrations in biological matrices (plasma, tissue homogenates) during tissue exposure/selectivity (STR) studies [12]. |

| AI-Powered Data Abstraction Platform | Software that uses Natural Language Processing (NLP) to convert unstructured clinical notes from EHRs into structured, usable data for patient cohort identification and trial enrollment [13]. |

| Validated Biomarker Assay (e.g., EEG for Event-Related Potentials) | Provides a functional, physiologically relevant, and interpretable endpoint for clinical trials, especially in complex areas like psychiatric drug development, where objective measures are critical [13]. |

| Federated Learning Platform | An AI training architecture that enables secure, multi-institutional data collaboration for model training without sharing raw patient data, protecting privacy while generating robust insights [13]. |

Visualized Workflows and Pathways

STAR Framework Evaluation Pathway

Modern Clinical Trial Data Flow

Strategic Toolbox: Core and Emerging Synthesis Methodologies

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This support center provides targeted assistance for researchers confronting the routine and complex challenges of total synthesis. The guidance below is framed within our broader thesis that a systematic and analytical approach is paramount for navigating the structural complexity inherent to natural products.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: My reaction is proceeding too slowly or not at all. What are the first things I should check?

A stalled reaction is a common hurdle. We recommend a systematic approach to identify the culprit [15].

- Step 1: Verify Reagents and Solvents. Check for common issues like anhydrous conditions if required. Ensure your solvents are dry and free of stabilizers that may inhibit reactivity. Confirm the purity and mass of solid reagents.

- Step 2: Assess the Reaction Environment. Is the reaction protected from air or moisture if necessary? Is the temperature accurately controlled? For reactions under an inert atmosphere, check for leaks in your Schlenk line or glovebox.

- Step 3: Propose and Test a Hypothesis. Based on your initial checks, form a hypothesis (e.g., "The reaction failed because the solvent was wet") [16]. Test this prediction directly (e.g., repeat the reaction with freshly dried solvent). If the result is negative, iterate with a new hypothesis (e.g., "The failure is due to a poisoned catalyst").

The logical flow for this diagnostic process can be summarized as follows:

FAQ 2: I have obtained a product, but its analytical data does not match the natural compound. How do I proceed?

Achieving analytical identity is the definitive goal of total synthesis [15] [17]. A discrepancy indicates a structural difference that must be resolved.

- Step 1: Gather Comprehensive Data. Don't rely on a single data point. Collect (^1)H NMR, (^13)C NMR, HRMS (High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry), and specific optical rotation data for both your product and the authentic natural sample.

- Step 2: Compare Systematically. Use the table below to compare your data and formulate questions that will guide your investigation.

| Analytical Method | Key Comparison Parameters | Questions to Ask |

|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy | Chemical shift (δ), integration, coupling constants (J), signal multiplicity. | Do the spectra confirm the correct carbon skeleton? Are the stereochemical relationships (from J-values) consistent? |

| Mass Spectrometry | Exact mass (from HRMS), fragmentation pattern. | Does the molecular formula match? Are there unexpected fragments suggesting a rearrangement? |

| Optical Rotation | Specific rotation [α] under identical conditions (solvent, temperature, concentration). | Is the absolute configuration correct, or is my product an enantiomer or diastereomer? |

- Step 3: Form a Hypothesis. Based on the data mismatch, propose a structural alternative (e.g., "My product has the epimeric stereochemistry at C-12"). Use retrosynthetic analysis to deconstruct both the target and your proposed structure, identifying where the synthetic path may have diverged [18].

- Step 4: Test Your Hypothesis. This may require synthesizing a different derivative to confirm stereochemistry, re-running a key step with a different stereocontrol method, or using advanced techniques like X-ray crystallography for definitive proof.

The workflow for resolving structural identity is a rigorous, iterative cycle:

FAQ 3: The yield for my key coupling step is very low. How can I optimize it?

Low yield in a complex synthesis can stem from many factors. A data-driven approach is key [19].

- Step 1: Identify the Problem. Is the low yield due to incomplete conversion, side reactions, or difficult purification?

- Step 2: Propose a Hypothesis. For example, "The palladium catalyst is deactivating under the reaction conditions."

- Step 3: Design Experiments. Set up small-scale, parallel reactions to test one variable at a time.

- Step 4: Analyze and Iterate. Use the data to confirm or revise your hypothesis.

A systematic optimization protocol can be visualized as a controlled exploration of the reaction parameter space:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials frequently employed in modern total synthesis campaigns to address specific challenges of structural complexity [18] [17].

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Chiral Ligands (e.g., BINAP, BOX ligands) | Imparts stereocontrol in asymmetric synthesis via metal-catalyzed reactions such as hydrogenation or C-C bond formation. Critical for setting absolute stereocenters. |

| Pd/Cu Catalysts | Facilitates key cross-coupling reactions (e.g., Sonogashira, Suzuki, Heck) for constructing the carbon skeleton. Essential for sp²-sp² and sp²-sp carbon bond formation. |

| Protecting Groups (e.g., TBS, Boc, Fmoc) | Temporarily masks reactive functional groups (e.g., alcohols, amines) to ensure chemoselectivity during multi-step syntheses. |

| Oxidizing/Reducing Agents | Selective agents (e.g., Dess-Martin periodinane for oxidation; DIBAL-H for selective reduction) enable precise functional group interconversions. |

| Enzymes / Biocatalysts | Used in chemoenzymatic synthesis for highly selective and sustainable reactions, such as asymmetric reductions or kinetic resolutions [17]. |

Structural simplification is a powerful strategy in medicinal chemistry for improving the efficiency and success rate of drug design. This approach involves simplifying large or complex lead compounds by truncating unnecessary groups, which can not only improve synthetic accessibility but also enhance pharmacokinetic profiles and reduce side effects [20]. The trend toward designing large hydrophobic molecules for lead optimization is often associated with poor drug-likeness and high attrition rates in drug discovery, a phenomenon known as "molecular obesity" [20]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for researchers implementing structural simplification strategies within their natural product synthesis and drug development workflows.

Core Principles of Structural Simplification

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts

What is structural simplification in drug discovery? Structural simplification is a lead optimization strategy that involves generating new drug analogues from large or complex lead compounds by systematically truncating unnecessary substructures. This approach aims to produce molecules with improved synthetic accessibility, favorable pharmacokinetic profiles, and reduced side effects [20] [21].

Why is reducing molecular complexity important? Reducing molecular weight and complexity has positive effects on pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles [20]. Less complex drugs are more likely to achieve better market success, as molecular complexity is associated with high attrition rates in drug development due to poor ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) properties [20].

What are the key steps in structural simplification? The typical process includes [21]:

- Analyzing molecular complexity (rings, chiral centers)

- Determining substructures important for biological activity

- Elucidating structure-activity relationships (SAR) and pharmacophores

- Removing unnecessary structural motifs

How does structural simplification differ from other optimization strategies? Unlike approaches that add complexity to improve potency, simplification deliberately removes redundant structural elements while maintaining or enhancing desired biological activity. This contrasts with traditional lead optimization that often increases molecular weight, lipophilicity, and ring counts [20].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Simplified analogues show significantly reduced potency

- Potential Cause: Truncation of essential pharmacophore elements.

- Solution:

- Prevention: Complete thorough SAR analysis before initiating truncation studies.

Problem: Simplified compounds exhibit poor solubility despite reduced molecular weight

- Potential Cause: Removal of polar functional groups or increased molecular planarity.

- Solution:

- Introduce minimal polar substituents at positions not critical for activity

- Consider isosteric replacement of hydrophobic groups with polar bioisosteres

- Evaluate physicochemical properties early in simplification cascade

- Prevention: Monitor calculated logP and polar surface area throughout design process.

Problem: Synthetic accessibility not improved despite structural simplification

- Potential Cause: Creation of new chiral centers or unstable structural motifs.

- Solution:

- Prevention: Apply retrosynthetic analysis early in simplification planning.

Key Experimental Workflows

The following workflow illustrates the core decision process in structural simplification projects:

Quantitative Guidelines for Simplification

Table 1: Molecular Complexity Metrics for Simplification Targets

| Parameter | High Complexity | Moderate Complexity | Simplification Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | >500 Da | 400-500 Da | <400 Da |

| Chiral Centers | ≥3 | 2 | ≤1 |

| Ring Systems | ≥4 | 3 | ≤2 |

| Rotatable Bonds | >10 | 7-10 | <7 |

| logP | >5 | 3-5 | <3 |

Source: Adapted from analysis of lead-drug pairs [20]

Case Studies and Practical Applications

FAQ: Implementation Questions

What are successful examples of structural simplification? Notable examples include:

- Morphine to simpler analgesics: The pentacyclic system of morphine was systematically simplified to various semisynthetic or synthetic analgesics (butophanol, pentazocine, pethidine, methadone) while retaining key pharmacophores [20] [21].

- Halichondrin B to Eribulin: The very complex marine natural product halichondrin B was simplified to eribulin mesylate, which retained antitumor activity while improving synthetic accessibility from approximately 120 steps to a practical synthesis [20].

- Myriocin to Fingolimod: A fungal metabolite was simplified to fingolimod, showing higher potency, improved physicochemical properties, and reduced toxicity [20].

How do I determine which structural elements are unnecessary? Several approaches can identify non-essential groups:

- Systematic deletion studies: Remove substructures one-by-one with biological testing

- Structure-based analysis: Examine ligand-target complexes to identify interacting groups [23]

- Pharmacophore modeling: Determine minimal structural features required for activity

- Natural product biosynthetic knowledge: Identify biosynthetic decorations not critical for activity [24]

What techniques facilitate structural simplification? Key methodological approaches include:

- Molecular docking: Predicts binding modes and identifies non-interacting regions [22]

- SAR analysis: Correlates structural features with biological activity

- Chemoselective synthesis: Enables functional group manipulation without protection [9]

- In silico ADMET prediction: Evaluates simplified compounds before synthesis

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Structural Simplification Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Simplification | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking Software (AutoDock, Gold, GLIDE) | Binding mode prediction and interaction analysis [22] | Identifying non-essential substructures not involved in target binding |

| Structure Visualization Tools (PyMOL, Chimera) | 3D structure analysis and pharmacophore mapping | Visualizing ligand-target interactions to guide truncation strategies |

| Natural Product Libraries | Source of complex lead compounds | Starting points for simplification campaigns |

| SAR Analysis Databases | Structure-activity relationship mining | Identifying tolerated modification sites |

| ADMET Prediction Platforms | Property optimization during simplification | Ensuring simplified compounds maintain favorable drug-like properties |

Advanced Applications and Integration

Troubleshooting Guide: Advanced Implementation

Problem: Unable to maintain selectivity after simplification

- Potential Cause: Removal of groups responsible for selective target recognition.

- Solution:

- Conduct counter-screening against related targets

- Analyze binding sites of related targets for differences

- Introduce minimal substituents that exploit target differences

- Utilize molecular dynamics to study binding stability [22]

- Prevention: Include selectivity assessment early in simplification cascade.

Problem: Synthetic routes remain challenging despite molecular simplification

- Potential Cause: The simplified structure contains reactive or incompatible functional groups.

- Solution:

- Implement protecting-group-free synthesis strategies [9]

- Employ chemoselective reactions that tolerate multiple functional groups

- Consider late-stage introduction of sensitive functional groups

- Utilize cascade reactions to build complexity efficiently

- Prevention: Apply retrosynthetic analysis considering functional group compatibility.

The following diagram illustrates the integration of structural simplification within the broader drug discovery pipeline:

Structural simplification represents a powerful approach for addressing the challenges of molecular complexity in natural product-based drug discovery. By systematically applying the troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and strategic frameworks outlined in this technical support resource, researchers can more effectively navigate the process of truncating unnecessary substructures while maintaining biological activity. The integration of modern computational methods, synthetic strategies, and analytical techniques enables rational simplification approaches that can significantly improve drug-likeness and development success rates.

Conceptual Foundations and FAQs

FAQ: What is bioinspired synthesis? Bioinspired synthesis is an approach where chemists design synthetic strategies for natural products by mimicking their proposed biosynthetic pathways in living organisms. This method uses nature's blueprints to efficiently construct complex molecules, often achieving rapid increases in molecular complexity through cascade reactions and other efficient transformations [25].

FAQ: How does bioinspired synthesis differ from traditional total synthesis? While traditional total synthesis may use any available synthetic method, bioinspired synthesis specifically imitates nature's proposed biochemical transformations. This often allows for more efficient and concise synthetic routes, shorter step counts, and the potential for divergent synthesis of multiple related natural products from a common intermediate [26].

FAQ: What are the main types of bioinspired strategies? Researchers typically categorize bioinspired approaches into three main types:

- Mimicking key cyclization steps: Developing synthetic methods that replicate nature's core skeleton-forming reactions [26].

- Following revised biosynthetic pathways: Investigating alternative biosynthetic routes when originally proposed pathways contradict chemical principles [26].

- Imitating skeletal diversification: Using a common intermediate to generate multiple natural products with distinct carbon skeletons, mirroring nature's divergent biosynthesis [26].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Issue: Low Yield in Biomimetic Cyclization Steps

Biomimetic cyclizations, such as the Prins-triggered double cyclization used in chabranol synthesis, are powerful but can suffer from low yields [25].

Systematic Troubleshooting Steps [27]:

- Identify the problem: Clearly define the specific reaction underperforming.

- List possible explanations: Consider catalyst/activator efficiency, substrate purity, stereoelectronic effects, reaction conditions (temperature, concentration, solvent), and potential side reactions.

- Collect data: Review analytical data (NMR, LC-MS) of starting materials and crude reaction mixtures. Check for byproducts or decomposition.

- Eliminate explanations: Systematically rule out factors. For example, if a reaction is highly sensitive to water, ensure all reagents and glassware are anhydrous.

- Check with experimentation: Design controlled experiments to test remaining hypotheses. Change only one variable at a time (e.g., activator stoichiometry, temperature gradient).

- Identify the cause: Based on experimental results, pinpoint the primary issue and implement a fix, such as optimizing Lewis acid concentration or protecting interfering functional groups.

Example from Literature: The bioinspired synthesis of chabranol uses a silyl cation to activate the aldehyde precursor for a key Prins cyclization. Troubleshooting this step would involve optimizing the source of the "formal silicon cation" and the reaction conditions to maximize the yield of the bicyclic intermediate 9 [25].

Issue: Failed Oxidative Cyclization Mimicking Biosynthesis

The biomimetic formation of the tetrahydrofuran ring in monocerin analogues relies on generating a para-quinone methide (pQM) intermediate followed by an oxa-Michael addition [25].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Confirm oxidant effectiveness: Test different oxidants (e.g., DDQ, MnO₂, hypervalent iodine reagents) to efficiently generate the reactive pQM intermediate.

- Verify stereochemical requirements: Ensure your substrate's stereochemistry allows for the desired cyclization trajectory. Molecular modeling can help assess feasibility.

- Control reaction environment: The oxa-Michael step can be sensitive to pH and protic solvents. Screen solvents and additives (acids, bases) to facilitate the cyclization.

- Check for competing pathways: The pQM intermediate is highly reactive and may be trapped by nucleophiles from the solvent or undergo polymerization. Using high dilution conditions or different solvents can mitigate this.

Issue: Inefficient Divergent Synthesis from a Common Intermediate

A major goal of bioinspired synthesis is to use a single advanced intermediate to access multiple natural products [26].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Re-evaluate the common intermediate: Confirm its structure and purity. Ensure it contains the necessary functional handles for diversification.

- Optimize individual diversification steps: Not all downstream reactions will be equally efficient. Treat each transformation as a separate optimization problem.

- Employ chemoenzymatic strategies: If chemical methods for diversification fail, consider engineered enzymes to perform specific, high-yielding late-stage modifications, as demonstrated in the synthesis of teleocidin derivatives [28] and fusicoccane diterpenoids [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bioinspired Prins Cyclization for Bicyclic Core Construction [25]

This protocol is adapted from the key step in the total synthesis of the diterpenoid chabranol.

- Objective: To construct the oxa-[2.2.1] bridged bicycle from a linear hydroxy aldehyde precursor.

- Reaction Mechanism: The reaction proceeds via activation of the aldehyde, triggering a Prins cyclization with a nearby alkene. The resulting carbocation is trapped intramolecularly by a tertiary alcohol.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Synthesize hydroxy aldehyde precursor 3 from phenyl sulfide 5 and chiral epoxide 6 via coupling, reduction, and selective oxidation.

- Cyclization:

- Charge a flame-dried round-bottom flask with hydroxy aldehyde 3 (1.0 equiv) under an inert atmosphere.

- Add dry dichloromethane (0.01-0.05 M concentration) and cool the solution to 0°C.

- Add a Lewis acid (e.g., TMSOTf; 1.5-2.0 equiv) dropwise via syringe.

- Stir the reaction mixture, allowing it to warm to room temperature over 2-12 hours. Monitor by TLC or LC-MS.

- Work-up: Quench the reaction by careful addition of a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate.

- Purification: Extract the aqueous mixture with dichloromethane (3x). Combine the organic layers, dry over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Isolation: Purify the crude residue (containing silylated bicycle 9) by flash column chromatography on silica gel.

Technical Notes:

- Critical: All reagents and glassware must be scrupulously dry to prevent hydrolysis of the Lewis acid and silyl ether products.

- The concentration of the substrate can significantly impact the reaction rate and yield. Test different dilutions if necessary.

- The diastereoselectivity of this cyclization is often high, as reported in the chabranol synthesis, leading to a single detectable diastereomer of the product [25].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for this protocol.

Protocol 2: Chemoenzymatic Synthesis for Scalable Production [28]

This protocol outlines a general strategy for producing complex natural products like teleocidin B, combining chemical and enzymatic synthesis.

- Objective: To achieve efficient, scalable production of complex monoterpenoid indole alkaloids using engineered enzymes.

- Key Strategy: Overcome bottlenecks in the biosynthetic pathway via protein engineering. For teleocidins, this involved fusing a reductase module to the P450 enzyme TleB to create a self-sufficient system, significantly boosting the production of the key intermediate indolactam V [28].

- General Workflow:

- Pathway Identification: Identify the biosynthetic gene cluster and key enzymatic steps in the natural product's pathway.

- Host Engineering: Select a suitable microbial host (e.g., E. coli). Engineer platform strains to overproduce central metabolic precursors [30].

- Enzyme Engineering: Identify rate-limiting enzymes. Use protein engineering (e.g., fusion tags, directed evolution) to improve catalytic efficiency, stability, and soluble expression in the heterologous host [28].

- Dual-Cell Factory Setup: Implement a co-culture system where different strains express complementary parts of the pathway to reduce metabolic burden and optimize overall titers [28] [30].

- Fermentation and Scale-up: Transfer the optimized system to a bioreactor for scalable production under controlled conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents, enzymes, and materials used in advanced bioinspired and chemoenzymatic syntheses, as cited in the literature.

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials for Bioinspired Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Lewis Acids (e.g., TMSOTf) | Activates carbonyls for key cyclization reactions like the Prins cyclization. [25] | Used to activate aldehyde 3 in the bioinspired synthesis of chabranol. [25] |

| Engineered P450 Enzymes (e.g., TleB) | Catalyzes oxidative cyclizations and complex C-H functionalizations that are challenging by traditional chemistry. [28] | A fused, self-sufficient TleB variant boosted indolactam V production to 868.8 mg L⁻¹. [28] |

| Heterologous Hosts (E. coli, S. cerevisiae) | Microbial chassis for expressing biosynthetic pathways and producing natural products via fermentation. [30] | A recombinant E. coli system produced 300 mg of teleocidin B isomers. [28] |

| Platform Strains | Pre-engineered microbial strains that overproduce central metabolites (e.g., geranyl pyrophosphate), providing a high-titer starting point for PNP pathways. [30] | Strains overproducing (S)-reticuline enable the biosynthesis of diverse benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. [30] |

| Oxidants (for pQM formation) | Generates reactive para-quinone methide (pQM) intermediates from phenolic precursors for oxidative cyclization. [25] | Proposed for tetrahydrofuran ring formation in monocerin-family natural products. [25] |

Visual Guide to Bioinspired Synthesis Workflow

The following diagram provides a generalized strategic workflow for planning and executing a bioinspired total synthesis project, integrating concepts from the reviewed literature.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my AI model fail to propose convergent synthetic routes for complex natural products?

A: This is often due to the search algorithm's scoring function prioritizing linear pathways. To encourage convergent synthesis, implement a Convergent Disconnection Score (CDScore). This score, as used in the ReTReK framework, evaluates potential disconnections based on their ability to split the target molecule into roughly equal-sized fragments, promoting more efficient synthesis trees. Furthermore, ensure your search algorithm, such as Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), is configured to use this score in its tree policy for selecting promising search directions [31].

Q2: My template-based model cannot find applicable reactions for novel, complex scaffolds. How can I improve its generality?

A: Template-based models are limited by their predefined rule libraries. For novel structures, consider these approaches:

- Switch to a template-free model: Models like BatGPT-Chem treat retrosynthesis as a sequence-to-sequence translation problem, converting product SMILES strings directly into reactant SMILES strings. This approach does not rely on a fixed template library and demonstrates better generalization for out-of-distribution molecules [32].

- Utilize a semi-template model: These models first identify the reaction center to generate intermediate synthons and then complete the precursors. This hybrid approach balances interpretability with improved generalization capability [32].

- Expand template applicability: If sticking with template-based methods, ensure your reaction templates consider the reaction center and its first-degree neighbors, which helps maintain chemical integrity and applicability [31].

Q3: The proposed precursors are chemically implausible or unstable. What is the cause and solution?

A: Chemically implausible suggestions can arise from:

- Biased Training Data: Models trained on noisy or highly biased public reaction data may learn incorrect transformations. Use curated datasets and consider incorporating chemical knowledge checks.

- Lack of Reaction Condition Knowledge: Many models focus only on the core transformation and ignore crucial elements like solvents, catalysts, or temperature. Using models that explicitly predict reaction conditions, such as BatGPT-Chem, which integrates this information end-to-end, can significantly improve the plausibility of proposed routes [32].

- Invalid Stereochemistry: When applying a predicted reaction, use reliable chemistry toolkits (e.g., the Reactor in the ChemAxon API) to correctly handle stereochemistry and regiochemistry during the transformation [31].

Q4: How can I guide the AI to prioritize synthetically accessible starting materials?

A: Integrate an Available Substances Score (ASScore) into your search algorithm. This score penalizes proposed precursors that are not found in a predefined database of commercially available or readily synthesized compounds (e.g., ZINC database). By factoring this score into the MCTS evaluation, the search is directed toward pathways that terminate in accessible starting materials [31].

Q5: What does "zero-shot prediction capability" mean, and why is it important for natural product synthesis?

A: Zero-shot prediction refers to a model's ability to make accurate predictions for reaction types or molecule classes that it did not see during training. This is crucial for natural product synthesis because these molecules often possess novel, complex scaffolds not well-represented in standard reaction databases. Models like BatGPT-Chem are developed with this capability, allowing them to propose synthetic pathways even for highly unique structures by leveraging broad chemical knowledge learned during pre-training [32].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: The retrosynthetic search is computationally expensive and slow for large, complex molecules.

- Solution: Adjust the expansion size in the MCTS algorithm. Research on the ReTReK model showed that performance improves with larger expansion sizes (e.g., top 50, 100, 300, or 500 predicted templates per step), but this increases computation. A balance must be struck based on available resources. The top-100 templates often provide a good balance between performance and speed [31].

Issue: The model proposes routes with reactions that are known to have low selectivity or yield.

- Solution: Implement a Selective Transformation Score (STScore). This score is designed to favor reactions that produce fewer byproducts. It can be incorporated as an adjustable parameter within the MCTS tree policy to guide the search toward higher-yielding, more selective transformations [31].

Issue: The AI consistently fails to disassemble complex ring systems effectively.

- Solution: Introduce a Ring Disconnection Score (RDScore). This strategy is particularly useful when the target has complex ring structures, as their construction often leads to simpler precursors. The RDScore helps the algorithm identify strategic bond disconnections within rings [31].

The performance of AI retrosynthesis tools is typically evaluated on benchmark datasets. The table below summarizes key quantitative data from relevant models and studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Retrosynthesis Tools and Components

| Model / Component | Key Metric | Performance | Context / Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| ReTReK's GCN Policy Network [31] | Top-1 Accuracy | 36.1% | 1-step retrosynthetic reaction prediction on Reaxys-based templates. |

| Top-50 Accuracy | 90.6% | ||

| Top-100 Accuracy | 93.8% | ||

| BatGPT-Chem [32] | Zero-shot Capability | Demonstrated | Effective retrosynthesis prediction on specialized, non-overlapping datasets (e.g., Suzuki-Miyaura, Buchwald-Hartwig). |

| Molecular Complexity Model [33] | Pair Accuracy (PA) | 77.5% | Accuracy in ranking molecular complexity compared to expert human assessment. |

| Functional Group Test (FGT) | 98.1% | Model correctly identified increased complexity after adding a functional group. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Implementing a Knowledge-Guided Retrosynthetic Search with MCTS

This protocol outlines the methodology for setting up a retrosynthetic search system similar to the ReTReK application, which integrates data-driven prediction with rule-based chemical knowledge [31].

Objective: To design a multistep synthetic route for a target molecule by leveraging a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm enhanced with retrosynthesis knowledge scores.

Materials:

- Hardware: A computer with significant computational resources (e.g., high-CPU/GPU servers).

- Software: A programming environment (e.g., Python) with libraries for cheminformatics (e.g., RDKit) and machine learning (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow).

- Data:

- Target Molecule: The complex molecule for which a synthetic route is needed.

- Reaction Database: A large, curated database of reactions (e.g., Reaxys, USPTO) for training the one-step prediction model.

- Starting Materials Database: A database of commercially available or easily accessible building blocks (e.g., ZINC database).

Procedure:

- Policy Network Training: Train a one-step retrosynthetic reaction prediction model (the policy network). A Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) is a suitable architecture. This model learns to prioritize a list of applicable reaction templates for any input molecule.

- MCTS Initialization: Define the root node of the search tree as the target molecule.

- Tree Search Iteration (Repeated until a satisfactory route is found or resources are exhausted):

- Selection: Traverse the tree from the root node by selecting the node with the highest value from a combination of the prediction score and the retrosynthesis knowledge scores (CDScore, ASScore, etc.).

- Expansion: When a leaf node is reached, use the policy network to expand the node by generating the top k most promising precursor suggestions (e.g., k=100).

- Rollout (Simulation): For each new node, perform a rapid simulation (e.g., using a simpler, faster policy) to estimate the potential of reaching starting materials.

- Update (Backpropagation): Update the node statistics (e.g., visit count, value score) along the traversed path based on the outcome of the simulation (e.g., success or failure in reaching starting materials).

- Route Extraction: Once the search is complete, extract the most promising synthetic route from the root (target) to the leaf nodes (starting materials).

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative loop of the MCTS algorithm as applied to retrosynthetic planning.

Diagram 1: MCTS Retrosynthesis Cycle

Protocol: Quantifying Molecular Complexity for Target Analysis

Objective: To assign a numerical complexity value to a target natural product, providing a benchmark to assess the challenge a synthesis poses and to compare different synthetic strategies.

Materials:

- Software: Access to a molecular complexity model, such as the Learning-to-Rank (LTR) GBDT model described by Tyrin et al. [33].

- Input: The SMILES string or molecular structure file of the target molecule.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Generate a valid SMILES string for your target molecule.

- Feature Calculation: Calculate or extract key molecular descriptors that the model uses. The most important features, as identified by SHAP analysis, are [33]:

- Molecular Weight

- Number of Aromatic Cycles

- Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA)

- SCScore (Synthetic Complexity Score)

- Model Application: Input the molecule's descriptor values into the pre-trained ranking model.

- Interpretation: The model outputs a relative complexity score. A higher score indicates a more complex molecule. This score can be used to track complexity changes during retrosynthetic analysis or to compare the overall challenge of synthesizing different candidate molecules.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Digital Tools and Databases for Computational Retrosynthesis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Retrosynthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Reaxys [31] [34] | Reaction Database | Provides a vast repository of historical chemical reactions and substances for training AI models and validating proposed routes. |

| ZINC Database [31] | Starting Materials Database | A curated collection of commercially-available compounds; used to define the search boundary for viable synthesis. |

| USPTO Dataset [34] | Reaction Database | A large, publicly available dataset of chemical reactions extracted from U.S. patents, commonly used for training template-based and template-free AI models. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | An open-source toolkit for Cheminformatics; used for manipulating molecules, handling SMILES, calculating descriptors, and applying reaction transforms. |

| SMILES Notation [34] [32] | Molecular Representation | A line notation for representing molecular structures as text, enabling the use of natural language processing (NLP) models for retrosynthesis. |

| BatGPT-Chem [32] | AI Model (LLM) | A large language model specialized for chemistry, capable of template-free, one-step retrosynthesis prediction with reaction condition suggestion and zero-shot capability. |

| DataWarrior [35] | Data Analysis Tool | A free program for data visualization and analysis, useful for calculating physicochemical properties and analyzing structure-activity relationships of precursors. |

Knowledge Integration & Strategic Pathway

Successfully integrating chemical knowledge into a data-driven AI framework is key to practical retrosynthesis planning. The following diagram illustrates how different knowledge scores can be incorporated into the search process to guide it toward more desirable synthetic routes.

Diagram 2: Knowledge-Guided AI Planning

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor Enzyme Performance in Kinetic Resolutions

Problem: An enzymatic kinetic resolution is proceeding with low enantioselectivity (E value) or low conversion, failing to provide the desired enantioenriched intermediate.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low enantioselectivity | Incorrect enzyme choice for substrate | Screen different biocatalysts (e.g., lipases, acylases) [36]. | Use a tailored enzyme variant developed via directed evolution [36]. |

| Low conversion rate | Suboptimal reaction conditions (pH, temperature) | Measure pH and temperature; run control experiments. | Optimize buffer, temperature, and co-solvent concentration [36]. |

| No reaction | Enzyme inactivation or incompatible functional groups | Check enzyme activity with a standard substrate; review substrate structure. | Ensure substrate lacks enzyme-inhibiting groups; use a fresh enzyme batch [36]. |

Experimental Protocol for Biocatalytic Kinetic Resolution:

- Reaction Setup: Dissolve the racemic substrate (e.g., 17) in an organic solvent like diisopropyl ether (0.1 M concentration) [36].

- Enzyme Addition: Add the biocatalyst (e.g., Lipase PS) and vinyl acetate as an acyl donor [36].

- Monitoring: Monitor the reaction progress by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) or chiral high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) until the kinetic resolution is complete (may take several days) [36].

- Workup: Filter to remove the immobilized enzyme and concentrate the filtrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify the product (e.g., enantiopure ester 18) using flash column chromatography to obtain the resolved material in high enantiomeric excess (e.g., 98:2 er) [36].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting a Multi-Step Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

Problem: A late-stage enzymatic transformation, such as an oxidation cascade, fails after a long sequence of chemical steps, jeopardizing the entire synthesis.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme does not accept synthetic intermediate | Subtle structural differences from natural substrate | Test the enzyme on a natural substrate; compare ( K_m ) values. | Employ protein engineering to adjust the enzyme's active site for better acceptance of the synthetic substrate [29]. |

| Low yield in enzymatic oxidation | Incompatibility of the enzyme with chemical functional groups on the synthetic intermediate | Check for functional groups that might inhibit or destabilize the enzyme. | Re-order the synthetic sequence or use protective groups to mask incompatible functionalities during the enzymatic step [36]. |

| Inability to scale up a chemoenzymatic step | Poor enzyme stability or co-factor regeneration issues under scaled conditions | Perform a small-scale reaction mimicking the production environment. | Develop a immobilized enzyme system or optimize co-factor recycling for larger scales [36]. |

Experimental Protocol for Late-Stage Enzymatic Oxidation:

- Enzyme Engineering: If the wild-type enzyme shows poor activity, perform rational protein engineering or directed evolution to generate a variant that accepts the synthetic intermediate [29].

- Reaction Setup: Incubate the chemically synthesized precursor with the engineered enzyme and necessary cofactors (e.g., NADPH, O₂) in an appropriate buffer.

- Process Optimization: For scalability, consider immobilizing the enzyme on a solid support and establishing a continuous flow system to improve stability and efficiency [36].

- Monitoring and Isolation: Monitor the reaction closely using LC-MS. Upon completion, extract and purify the product (e.g., the final natural product) using standard techniques [29].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary strategic approaches for incorporating biocatalysis into a total synthesis plan? Based on recent literature, there are four main conceptual approaches [36]:

- Providing Enantioenriched Intermediates: Enzymes, like lipases, are used in a supporting role for kinetic resolutions or desymmetrizations to generate chiral building blocks, without altering the core synthetic logic [36].

- Evaluating Biosynthetic Hypotheses: Chemically synthesized intermediates are used to probe the function of enzymes in biosynthetic pathways, validating or discovering biological functions [36].

- Inspiring Retrosynthetic Disconnections: The known reactivity of an enzyme is used as the central, simplifying transform (a "T-goal") in designing the synthetic route from the outset [36].

- Filling Gaps in Methodology: A disconnection is proposed for which no chemical method exists, prompting the discovery or engineering of a new "reaction" to achieve the transformation [36].

Q2: How can I improve the efficiency and success of my chemoenzymatic synthesis? Efficiency is achieved by strategically leveraging the strengths of both chemical and biological catalysis [36] [29]: