Optimizing Purification Protocols for Complex Natural Extracts: Strategies for Enhanced Bioactivity and Reproducibility

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing purification protocols for complex natural extracts.

Optimizing Purification Protocols for Complex Natural Extracts: Strategies for Enhanced Bioactivity and Reproducibility

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing purification protocols for complex natural extracts. It explores the foundational principles of extract complexity and standardization challenges, details advanced methodological approaches including macroporous resin and chromatography techniques, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common purification issues. Through comparative analysis of validation techniques and bioactivity assessments, this resource aims to bridge the gap between laboratory-scale purification and industrial application, supporting the development of standardized, high-quality natural products for biomedical research.

Understanding Complex Natural Extracts: Composition, Challenges, and Standardization Needs

FAQs: Addressing Core Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why do my natural extract bioactivity results show poor reproducibility between batches?

Batch-to-batch variability in natural extract bioactivity often stems from inconsistencies in the starting material or extraction process. To ensure reproducibility:

- Standardize Plant Material: Document plant species, geographic origin, harvest time, and plant part used [1] [2].

- Control Extraction Parameters: Maintain consistent solvent type, temperature, pH, and extraction duration [1]. Advanced techniques like Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) can improve reproducibility by offering better control over parameters [1] [3].

- Implement Chemical Profiling: Use HPLC-MS or GC-MS to create a chemical fingerprint of each batch and confirm the presence and concentration of key marker compounds [4] [2].

FAQ 2: How can I quickly identify known compounds in my extract to avoid re-isolating them?

The process of identifying known compounds early is called dereplication [5]. Implement this workflow:

- Hyphenated Analytical Techniques: Use LC-HRMS (Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry) for accurate mass data and preliminary identification [6] [7].

- Database Comparison: Compare acquired MS/MS spectra and retention times against natural product databases [5].

- HPLC-based Activity Profiling: Couple HPLC separation with on-line or off-line bioactivity assays to pinpoint which chromatographic peaks correspond to the bioactivity, focusing isolation efforts only on novel or active unknowns [5].

FAQ 3: My purification yields are low and the compounds seem degraded. What am I doing wrong?

Low yields and degradation often result from suboptimal extraction or purification conditions.

- Avoid Harsh Conditions: Prolonged exposure to high heat, extreme pH, or oxygen can degrade thermolabile compounds like flavonoids and polyphenols [1]. Consider green techniques like UAE or MAE which are faster and operate at lower temperatures [1] [3].

- Optimize Stationary/Mobile Phases: For chromatography, select phases orthogonal to your analytical profiling method. Method transfer from analytical to semi-preparative scale using modeling software can maintain resolution and improve yield [7].

- Monitor in Real-Time: Use semi-preparative HPLC coupled with UV, MS, or Evaporative Light Scattering Detection (ELSD) to accurately trigger collection of target compounds and avoid degradation [7].

FAQ 4: What is the most efficient strategy to isolate a specific bioactive compound from a complex extract?

A targeted isolation strategy is most efficient [7]:

- Comprehensive Metabolite Profiling: First, use UHPLC-HRMS to thoroughly annotate the metabolites in your crude extract.

- Peak Prioritization: Based on dereplication results, biological assay data, or metabolomics, select the LC peak(s) of interest.

- Method Transfer: Scale up the analytical UHPLC separation method to semi-preparative HPLC, ensuring the selectivity is maintained to isolate the target compound efficiently.

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Extraction and Purification

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low extraction yield | Inefficient cell disruption; wrong solvent polarity | Adopt modern techniques (e.g., UAE, MAE); match solvent polarity to target compounds (polar solvents for flavonoids, non-polar for terpenoids) [1] |

| Loss of bioactivity during processing | Degradation of thermolabile compounds | Use low-temperature techniques (UAE, SFE); reduce processing time; consider enzyme-assisted extraction for gentle cell wall breakdown [1] |

| Insufficient chromatographic resolution | Co-elution of numerous compounds | Use orthogonal separation (HILIC for polar compounds); employ columns with smaller particles (<2µm) for higher efficiency [7] [8] |

| Cannot identify metabolites | Signal overlap in NMR; low abundance | Combine HPLC fractionation with microprobe NMR; use HRMS/MS for structural information [5] [8] |

Table 2: Analytical Technique Selection Guide

| Technique | Best For | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS / HRMS [4] [7] | Dereplication; metabolite profiling | High sensitivity; provides molecular weight and fragmentation data | Requires standards for absolute confirmation; can ionize some compounds poorly |

| GC-MS [4] [5] | Volatile compounds, primary metabolites | Excellent separation; large spectral libraries | Requires volatile or derivatized samples |

| NMR Spectroscopy [6] [8] | De novo structure elucidation; quantification | Universal detector; provides definitive structural information | Lower sensitivity; signal overlap in complex mixtures |

| HPLC-NMR [6] [5] | Identifying unknowns in mixtures | Reduces complexity by coupling separation with powerful detection | Technically complex; expensive |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Integrated Metabolite Profiling for Targeted Isolation

Objective: To characterize a complex plant extract and isolate a specific, prioritized compound [7].

Materials:

- Equipment: UHPLC system coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer, semi-preparative HPLC system, suitable columns.

- Software: Chromatographic modeling software, natural product databases.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a crude extract using an optimized method (e.g., UAE with 70% ethanol).

- Analytical Profiling:

- Inject an aliquot onto the UHPLC-HRMS system.

- Use a generic, wide-scope gradient (e.g., 5-100% acetonitrile in water) for comprehensive separation.

- Acquire data in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode to get HRMS and MS/MS data for all major peaks.

- Dereplication & Prioritization:

- Process data to annotate metabolites by comparing accurate mass and MS/MS spectra against databases.

- Correlate chromatographic peaks with bioassay data if available.

- Select the target peak for isolation based on novelty or bioactivity.

- Method Transfer to Semi-Preparative HPLC:

- Use modeling software to transfer the analytical separation conditions to a semi-preparative scale.

- Ensure the mobile phase is compatible with fraction collection (e.g., use volatile buffers).

- Isolation:

- Inject the crude extract onto the semi-prep HPLC.

- Use the transferred method. Monitor with UV and/or MS.

- Collect the fraction corresponding to the retention time of the target compound.

- Evaporate the solvent to obtain the purified compound.

Protocol 2: HPLC-NMR for Identification of Unknown Metabolites

Objective: To isolate and identify a previously unknown metabolite from a complex biological matrix like urine or feces [8].

Materials: HPLC system, fraction collector, NMR spectrometer with a microprobe, HILIC column, deuterated solvents.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Pre-treat the biological sample (e.g., centrifugation, filtration) to remove particulates.

- HPLC Fractionation:

- Use a HILIC column for improved separation of polar metabolites.

- Run a gradient suitable for the sample (e.g., 95% to 65% acetonitrile).

- Collect fractions at fixed time intervals (e.g., 1-minute) into 96-well plates.

- NMR Analysis:

- Evaporate the solvent from selected fractions and re-dissolve in deuterated solvent.

- Transfer the sample to a microprobe NMR tube.

- Acquire 1D and 2D NMR spectra (e.g., 1H, COSY, HSQC) for structural elucidation.

- Data Integration: Combine the chromatographic retention behavior with the detailed structural information from NMR to confirm the identity of the unknown metabolite.

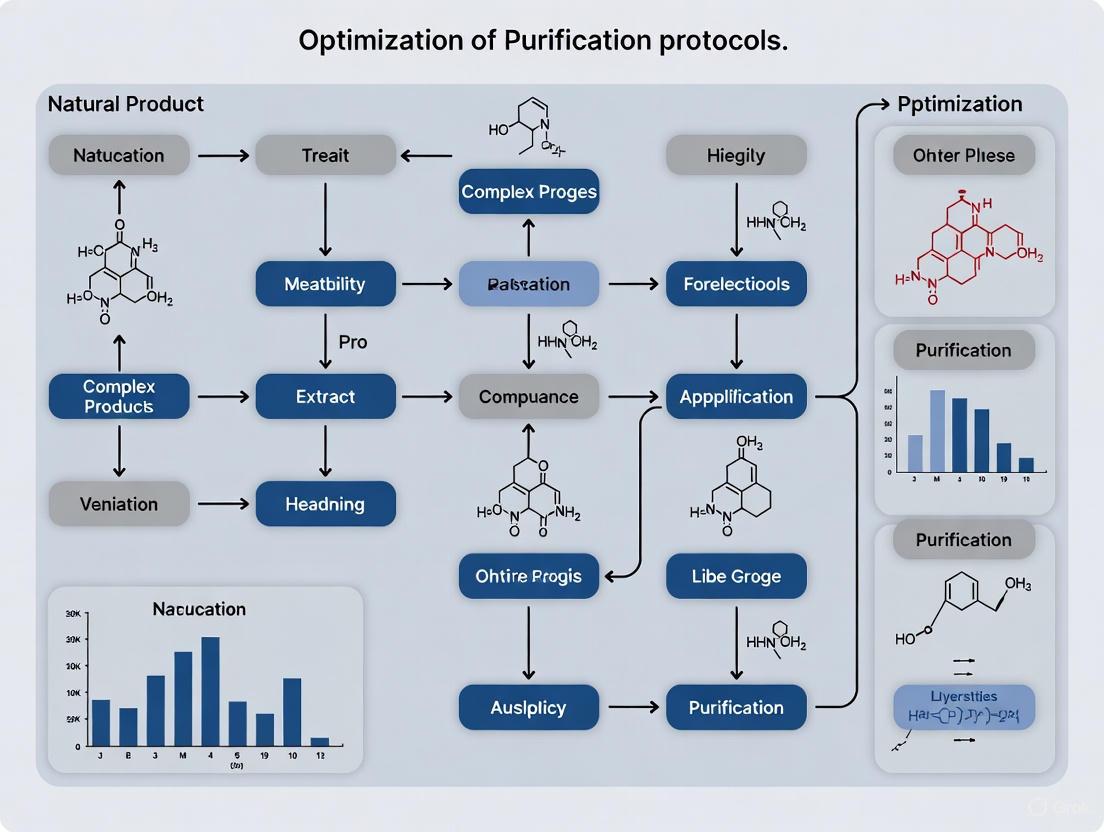

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Targeted Isolation Workflow

Diagram 2: Analytical Techniques for Metabolite ID

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Natural Products Research

| Item | Function & Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HILIC Column [8] | Separation of highly polar metabolites in complex biological matrices (e.g., urine, feces) that are poorly retained by standard reversed-phase columns. | Essential for comprehensive metabolome coverage. |

| UHPLC with sub-2µm particles [7] | Provides high-resolution, high-speed chromatographic separations for complex extract profiling prior to isolation. | Foundation for efficient method transfer to semi-prep. |

| Microprobe NMR [8] | Enables high-sensitivity NMR analysis of limited sample quantities, such as HPLC fractions. | Crucial for structure elucidation when sample is scarce. |

| Semi-Preparative HPLC Columns [7] | Scaling up analytical separations to milligram or gram scale for the isolation of pure natural products. | Select a phase that matches analytical profiling. |

| Evaporative Light Scattering Detector (ELSD) [7] | A universal detector for semi-prep HPLC that does not require chromophores, useful for compounds with weak UV absorption. | |

| Green Extraction Solvents [3] | Replace toxic solvents like n-hexane. Examples include ethanol-water mixtures, supercritical CO₂. | Reduces toxicity and environmental impact while maintaining efficiency. |

This technical support center addresses the core challenges—variability, reproducibility, and bioactivity preservation—that researchers face when purifying bioactive compounds from complex natural extracts. The guidance below provides targeted troubleshooting and detailed protocols to help you develop robust and reliable purification methods.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Purification Challenges

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | Incomplete cell lysis or disruption [9] [10]. | Increase homogenization time; use enzymatic (e.g., Proteinase K) or sonication methods for thorough lysis [9] [10]. |

| Overloaded purification column [11] [10]. | Reduce the amount of starting material to match the column's binding capacity [11]. | |

| Incomplete elution of target molecules [12] [9]. | Increase elution buffer volume; incubate for 5-10 minutes at room temperature before centrifugation; use a second elution step [11]. | |

| Low Purity / High Background | Inadequate washing steps [9]. | Increase number or volume of wash steps; optimize wash buffer composition for higher stringency (e.g., adjust salt concentration) [9]. |

| Carryover of impurities (proteins, salts) [12] [10]. | Ensure proper centrifugation to remove all flow-through; avoid column tip contact with waste; for salt carryover, add an extra wash step [11]. | |

| Loss of Bioactivity | Degradation by residual nucleases or proteases [10]. | Keep samples on ice; use lysis buffers with denaturants like guanidine salts; flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen for storage [10]. |

| Harsh extraction or elution conditions [1]. | For sensitive compounds like polyphenols, use milder techniques (e.g., Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction) and lower temperatures [1]. | |

| Poor Reproducibility | Inconsistent sample preparation [13]. | Standardize starting material (plant part, developmental stage) [13] and grinding process to a uniform powder [14]. |

| Unoptimized or variable purification parameters [14] [15]. | Strictly control and document all parameters, including solvent concentration, pH, temperature, and flow rates [14] [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can I minimize batch-to-batch variability in my natural extract purifications?

Batch-to-batch variability often stems from inconsistencies in the starting plant material and extraction process. To minimize this:

- Standardize Your Source: Use plant material from the same species, organ (e.g., leaf, husk), geographic origin, and harvesting time [13].

- Control Processing: Clean and dry raw material at low temperatures to preserve heat-labile compounds, then grind it into a fine, uniform powder to maximize surface area for consistent extraction [13].

- Optimize and Fix Protocols: Use design-of-experiment (DoE) approaches like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to find the optimal extraction conditions, then adhere strictly to the finalized protocol for all subsequent batches [14].

What are the best practices for preserving the bioactivity of purified compounds?

Bioactivity is closely linked to the structural integrity of bioactive compounds, which can be damaged during purification.

- Choose Gentle Techniques: Opt for modern, efficient methods like Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE). UAE uses acoustic cavitation to disrupt cells at lower temperatures, which better preserves heat-sensitive flavonoids and polyphenols compared to traditional Soxhlet extraction [1].

- Optimize Solvent Systems: The choice of solvent critically impacts the compounds you extract. Aqueous ethanol (e.g., 50-70%) is often effective for polar antioxidants like polyphenols and is considered a safe "green" solvent [13]. The optimal solvent must be determined for your specific compound and application.

- Maintain Cold Conditions: Perform purifications at 4°C when possible and use protease or nuclease inhibitors to prevent degradation [9]. Store purified samples at -80°C in appropriate buffers [9].

My purification resin loses efficiency quickly. How can I improve its longevity?

Rapid resin degradation is often caused by contaminants in the crude extract.

- Clarify Your Sample: Always centrifuge or filter crude extracts before loading them onto the column to remove particulate matter that can clog the resin [10].

- Follow Regeneration Protocols: After each run, follow the manufacturer's instructions for cleaning and regenerating the resin with stringent buffers to remove strongly bound impurities.

- Avoid Overloading: Do not exceed the resin's binding capacity, as this can cause fouling and reduce its effective life [11].

Why is my purified compound inactive in downstream biological assays?

Inactivity after purification suggests the target molecule was denatured or inactivated during the process.

- Verify Activity Post-Purification: Always check the activity of your final purified product using a quick in vitro bioassay (e.g., DPPH/ABTS for antioxidants) [14] [13] to confirm bioactivity was retained.

- Check for Cofactor Loss: Some proteins and enzymes require cofactors (e.g., metal ions) for activity. If these are removed during purification, you may need to add them back to the assay buffer [9].

- Review Purification Buffers: Ensure that the buffers used during purification are compatible with downstream assays. For example, high salt concentrations or harsh detergents can inhibit enzymatic activity in assays [9].

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction and Macroporous Resin Purification of Polyphenols

This optimized protocol for purifying polyphenols from plant husks (e.g., pecan) can be adapted for other plant materials [14].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Dry plant material at 60°C and grind into a fine powder. Sieve through a 40-mesh screen for uniform particle size [14].

2. Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction:

- Weigh 1 g of powder and add 15 mL of 58% ethanol (v/v) as the extraction solvent.

- Perform extraction in an ultrasonic bath set to 160 W power and 57°C for 60 minutes.

- Centrifuge the mixture at 3,500 rpm for 10 minutes. Collect the supernatant as the crude polyphenol extract [14].

3. Macroporous Resin Purification:

- Select a suitable macroporous resin (e.g., D-101 for pecans, AB-8 for wampee) [14] [15].

- Adjust the crude extract to a concentration of 2 mg/mL and set the pH to 4.

- Load the sample onto the resin column at a controlled flow rate of 2 mL/min.

- Wash the column with a mild buffer (e.g., distilled water) to remove unbound impurities.

- Elute the bound polyphenols using 70% ethanol at a flow rate of 3 mL/min.

- The purity of polyphenols can increase significantly (e.g., from 31.45% to over 69%) after this step [14].

Protocol 2: Assessing Antioxidant Activity of Purified Extracts

This standard procedure evaluates the bioactivity of purified extracts, a critical step after purification [14] [13].

1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay:

- Prepare a 0.1 mM solution of DPPH in methanol.

- Mix equal volumes (e.g., 1 mL each) of the purified extract at various concentrations and the DPPH solution.

- Incubate the mixture in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Measure the absorbance of the solution at 517 nm.

- Calculate the radical scavenging activity (%) using the formula:

(1 - Asample / Acontrol) * 100where A_control is the absorbance of a DPPH solution without extract [14].

2. ABTS Radical Scavenging Assay:

- Generate the ABTS•+ cation by reacting equal volumes of 7 mM ABTS solution and 2.45 mM potassium persulfate and allowing it to stand in the dark for 12-16 hours.

- Dilute the ABTS•+ solution with ethanol or buffer until its absorbance at 734 nm is about 0.70 ± 0.02.

- Mix the purified extract with the diluted ABTS•+ solution and measure the absorbance at 734 nm after 6 minutes of incubation.

- Calculate the percentage inhibition as in the DPPH assay [14] [13].

Purification Workflow and Decision Pathway

Critical Point Analysis and Resolution Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are essential for successful purification of bioactive compounds from natural extracts.

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Macroporous Resins (D-101, AB-8) | Used for selective adsorption and purification of polyphenols and flavonoids based on pore size and surface functional groups [14] [15]. |

| Ethanol (Aqueous Solutions) | A safe, "green" solvent for extracting polar bioactive compounds like polyphenols; optimal concentration is often 50-70% [14] [13]. |

| DPPH / ABTS | Stable radicals used in spectrophotometric assays to quantitatively measure the free radical scavenging (antioxidant) activity of purified extracts [14] [13]. |

| Proteinase K & RNase A | Enzymes used during sample lysis and preparation to degrade contaminating proteins and RNA, which improves the purity of the target molecule (e.g., DNA or other bioactives) [11] [10]. |

| Guanidine Thiocyanate (GTC) | A potent chaotropic agent and denaturant found in lysis and binding buffers. It denatures proteins and nucleases, protecting the target molecule from degradation and facilitating binding to silica columns [16] [10]. |

Understanding ConPhyMP: A Framework for Reproducibility

What is the main purpose of the ConPhyMP guidelines? The Consensus statement on the Phytochemical Characterisation of Medicinal Plant extracts (ConPhyMP) provides best practice guidelines to ensure the reproducibility and accurate interpretation of pharmacological, toxicological, and clinical studies using medicinal plant extracts [17]. It addresses the unique challenges posed by these complex, multi-component mixtures.

What unique challenges do medicinal plant extracts present? Unlike single chemical entities, medicinal plant extracts are complex mixtures where the identities and quantities of active ingredients are often not fully known [17]. Their composition can vary based on the preparation method and the source plant material, which directly impacts the reproducibility and interpretation of research findings [17].

The ConPhyMP Plant Extract Classification System

The ConPhyMP project introduced a framework centered on three main types of extracts to guide characterization requirements [17].

Table: ConPhyMP Extract Classification and Characterization Requirements

| Extract Type | Chemical Definition Level | Typical Analytical Methods | Primary Research Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type A: Fully Characterized | All constituents are identified and quantified. | Quantitative NMR (qNMR), LC-MS with authentic standards. | Mechanistic studies, lead compound isolation. |

| Type B: Standardized/Profiled | Active compounds or chemical markers are identified and quantified. | HPLC-DAD/ELSD, HPTLC, GC-MS with reference compounds. | Quality control, most pharmacological studies. |

| Type C: Partially Characterized | Limited chemical information is available (e.g., fingerprint). | HPTLC, simple HPLC-UV without full identification. | Preliminary screening, traditional medicine studies. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Our extract is a complex mixture. What is the minimum level of characterization required for publication? For research intended for publication, an extract should at minimum be classified as a Type B (Standardized) extract [17]. This requires you to identify and quantify one or more active principles or chemical markers using a validated method like HPLC or HPTLC. A simple chromatographic fingerprint (Type C) is generally insufficient for journals that endorse these guidelines.

2. How should we describe the starting plant material in our manuscript? The ConPhyMP guidelines emphasize a detailed description of the plant material to ensure traceability and reproducibility [17]. Essential information to report includes:

- Taxonomy: Genus, species, author, and subspecies or variety.

- Voucher Specimen: A unique voucher number and the herbarium where it is deposited.

- Source: Geographical origin and time of collection.

- Part Used: The specific plant part used (e.g., leaves, roots, bark).

3. We see synergistic effects in our extract. How can we prove it? ConPhyMP highlights that demonstrating true synergy is exceptionally complex and requires elaborate experimental designs, such as systematic combination studies and isobolographic analysis [17]. For complex extracts, it is often more feasible to focus on thoroughly characterizing the extract (as a Type A or B) and reporting its combined biological effect rather than attempting to deconvolute complex multi-target interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Extract Characterization

| Item / Reagent | Critical Function in Characterization |

|---|---|

| Analytical Reference Standards | Pure chemical compounds used to identify and quantify markers/actives in the extract via HPLC, HPTLC, or GC. |

| Validated Solvents & Reagents | High-purity solvents for extraction and chromatography to prevent contamination and ensure reproducible results. |

| Chromatography Columns & Plates | HPLC/UPLC columns (e.g., C18) and HPTLC plates are the physical media for separating complex mixtures. |

| Mass Spectrometry-Grade Solvents | Essential for LC-MS or GC-MS analysis to minimize ion suppression and background noise. |

| Stable Cell Lines for Bioassay | Genetically engineered cells (e.g., with reporter genes) provide consistent, reproducible models for testing extract activity. |

Experimental Protocol: Key Analytical Workflows

The following diagram and protocols outline core characterization workflows advocated by the ConPhyMP guidelines.

1. High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography (HPTLC) for Fingerprinting HPTLC is a robust, cost-effective method for creating a characteristic fingerprint of an extract [17].

- Sample Application: Apply test extract and reference standard solutions as bands on an HPTLC plate.

- Chromatogram Development: Develop the plate in a saturated twin-trough chamber with a suitable mobile phase.

- Derivatization & Documentation: Derivatize the plate with a suitable reagent (e.g., anisaldehyde-sulfuric acid for terpenes) and document the chromatogram under white light UV light (254 nm and 366 nm) before and after derivatization.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Rf values for the bands and compare the fingerprint with reference standards.

2. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for Quantification HPLC with UV (DAD) or MS detection is the standard for quantifying specific markers [17].

- Method Development & Validation:

- Column: Use a reversed-phase C18 column.

- Mobile Phase: Optimize a gradient of water and acetonitrile/methanol with modifiers.

- Validation: Validate the method for linearity, precision, accuracy, and limits of detection and quantification (LOD/LOQ) according to ICH guidelines.

- Sample Analysis & Quantification:

- Prepare calibration curves using authentic reference standards.

- Inject the standardized extract solution and quantify the target compounds against the calibration curve.

- Report the content of each marker compound as a percentage of the extract weight.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How does the source of my plant material impact the final extract? The chemical composition of plant materials is significantly influenced by genetic factors, environmental conditions (such as climate and soil), agricultural practices, and the timing of the harvest [18]. This natural variation means that the same plant species grown in different locations or harvested in different seasons can produce extracts with varying profiles of bioactive compounds, directly affecting experimental reproducibility and biological activity [2] [1] [18].

2. What is the single most important factor to control for consistent extraction? While multiple factors are important, the extraction solvent is fundamentally the most critical as it primarily determines which compounds are solubilized. The principle of "like dissolves like" applies: polar solvents (e.g., water, ethanol) extract hydrophilic compounds like flavonoids and phenolics, while non-polar solvents (e.g., hexane, chloroform) extract lipophilic compounds like terpenoids and carotenoids [1] [19]. Consistent solvent selection is the first step toward reproducible extracts.

3. My extracts show inconsistent bioactivity. Could pre-processing be the cause? Yes, absolutely. The particle size of your ground plant material is a major pre-processing factor. Reduced particle size increases the surface area exposed to the solvent, which can greatly enhance extraction yield and efficiency [18]. Inconsistent grinding leads to uneven extraction, resulting in batch-to-batch variability. Always use a standardized milling and sieving protocol to ensure a consistent starting powder.

4. Are "natural" extracts safer or more effective than synthetic ingredients? Not necessarily. From a chemical perspective, a molecule is identical whether it is synthesized in a lab or extracted from a plant, and your body reacts to its structure, not its source [20]. Natural extracts can contain variable levels of active compounds and may carry natural contaminants like heavy metals or pesticide residues [20]. Synthetically produced "nature-identical" compounds can offer higher purity, consistency, and sustainability [20].

5. How do I report my extract details for publication? Best practice guidelines, such as the ConPhyMP statement, recommend transparently reporting the following [2] [18]:

- Plant Material: Botanical name, plant part used, geographic origin, and time of harvest.

- Extraction Protocol: Solvent type and concentration, method (e.g., maceration, UAE, MAE), temperature, duration, and plant-to-extract ratio.

- Characterization: Chemical profiling data (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS) to define the composition.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Yield or Inconsistent Extraction Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Suboptimal Solvent System

Cause 2: Inefficient Cell Disruption

- Solution: Transition from traditional maceration to modern methods that enhance cell wall rupture.

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): Uses acoustic cavitation to break cell walls, improving yield at lower temperatures and shorter times, which is ideal for heat-sensitive flavonoids [1] [19].

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): Heats the internal moisture of plant cells rapidly, causing them to rupture and release contents more efficiently [19].

- Solution: Transition from traditional maceration to modern methods that enhance cell wall rupture.

Cause 3: Uncontrolled Natural Variation in Starting Material

- Solution: Implement a rigorous quality control system for your raw materials.

- Source Control: Obtain plant material from standardized, documented sources when possible.

- Standardization: Characterize the starting material using a relevant pharmacopeial standard if available [18].

- Pre-processing: Standardize drying, grinding, and sieving procedures to create a homogeneous powder [18].

- Solution: Implement a rigorous quality control system for your raw materials.

Problem: Loss of Bioactivity in Final Extract

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Degradation of Heat-Sensitive Bioactives

- Solution: Avoid prolonged exposure to high heat. If using Soxhlet or other heated methods, switch to milder techniques like UAE or enzyme-assisted extraction, which preserve the structural integrity of thermolabile compounds like certain polyphenols and flavonoids [1].

Cause 2: Inconsistent Plant-to-Extract Ratio and Misleading Standardization

- Solution: Understand and correctly apply the plant-to-extract ratio. This ratio describes the amount of starting plant material used to produce a given quantity of extract [18]. It is only a partial descriptor and does not guarantee consistent composition or bioactivity. For meaningful standardization, move beyond a single marker compound and employ chemical fingerprinting (e.g., via HPLC) to ensure a consistent and complex phytochemical profile [2] [18].

Problem: Extract is Too Complex with Unwanted Compounds

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Lack of Selectivity in Extraction

- Solution: Employ sequential or targeted extraction strategies.

- Sequential Extraction: Use a series of solvents of increasing or decreasing polarity to fractionate the extract [19].

- Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE): Uses specific enzymes (e.g., cellulases, pectinases) to break down plant cell walls, selectively releasing intracellular compounds or hydrolyzing unwanted macromolecules, thereby improving the selectivity for target bioactives like glycosides or polysaccharides [1].

- Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE): Often using CO₂, SFE is highly tunable by adjusting pressure and temperature, allowing for selective extraction of target compounds and leaving behind unwanted pigments or resins [1] [19].

- Solution: Employ sequential or targeted extraction strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Extraction Techniques

| Technique | Mechanism | Key Parameters | Impact on Yield & Bioactivity | Best for Compound Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration/Soxhlet (Traditional) [1] [19] | Solvent diffusion, often with heat. | Solvent type, temperature, time. | Lower efficiency, long extraction time. Risk of thermal degradation. | Stable, non-polar compounds. |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) [1] [19] | Acoustic cavitation disrupts cell walls. | Amplitude, time, temperature. | Higher yields, shorter time. Preserves heat-sensitive antioxidants, leading to higher bioactivity. | Polyphenols, Flavonoids. |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) [1] [19] | Internal heating causes cell rupture. | Power, solvent volume, time. | Rapid, high efficiency. Reduced solvent consumption. | Essential oils, pigments. |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) [1] [19] | Solvation with supercritical fluids (e.g., CO₂). | Pressure, temperature, modifier. | Highly selective, solvent-free. Yields high-purity extracts. | Lipids, essential oils, terpenoids. |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) [1] | Enzymatic hydrolysis of cell walls. | Enzyme type, pH, incubation time. | Improved yield of bound compounds; enhances bioavailability. | Glycosides, polysaccharides, oils. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Extraction & Purification | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents (Polar)e.g., Ethanol, Methanol, Water [1] [19] | Dissolve and extract hydrophilic compounds. | Ethanol-water mixtures are recommended for phenolic compounds and are considered safer (greener) than pure methanol [19]. |

| Solvents (Non-Polar)e.g., Hexane, Chloroform, Ethyl Acetate [1] [19] | Dissolve and extract lipophilic compounds. | Effective for terpenoids, carotenoids, and fixed oils. Often replaced by greener alternatives like supercritical CO₂ [19]. |

| Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC) Resin [21] [22] | Purifies recombinant proteins via affinity to polyhistidine-tags. | The first choice for capture step in protein purification from complex lysates. Works under native or denaturing conditions [21]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Resin [21] | Separates biomolecules based on molecular size/hydrodynamic volume. | An essential "polishing" step to remove aggregates and contaminants after the initial capture [21]. |

| Ion Exchange Chromatography (IEX) Resin [21] | Separates proteins based on their net surface charge. | Used as an intermediate or polishing step. Can be anion or cation exchange [21]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Standardized Preparation of a Phytochemically Characterized Plant Extract

This protocol is designed to minimize variability for research purposes, based on the ConPhyMP best practice guidelines [2].

1. Plant Material Authentication and Pre-processing: * Authentication: Obtain a voucher specimen from a qualified botanist. Document the plant species, part used, geographic origin, and harvest date. * Drying: Dry the plant material under controlled, low-temperature conditions (e.g., <40°C) to prevent thermal degradation. * Milling and Sieving: Mill the dried material and pass it through a standardized sieve (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mm mesh) to ensure a consistent particle size.

2. Extraction Optimization (Initial Scoping): * Solvent Selection: Based on the literature for your target compound class, test 2-3 solvents of different polarities (e.g., water, 50% ethanol, 80% methanol). * Method Screening: Compare a traditional method (maceration) with an advanced method (UAE) for efficiency. * UAE Protocol: Mix 1 g of plant powder with 20 mL of solvent in a sealed tube. Sonicate in an ultrasonic bath for 15 minutes at 40°C. Centrifuge at 10,000 x g for 10 minutes. Collect the supernatant. Filter through a 0.45 µm membrane.

3. Chemical Characterization (For QC and Reporting): * Total Phenolic/Flavonoid Content: Use spectrophotometric assays (e.g., Folin-Ciocalteu for phenolics) to get a preliminary quantitative measure. * Chromatographic Profiling: Analyze the extract by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with a photodiode array detector. This creates a chemical "fingerprint" that should be consistent across batches for reproducible research [2].

4. Standardization and Storage: * Documentation: Calculate and report the Plant-to-Extract ratio [18]. * Concentration: Concentrate the extract under reduced pressure (rotary evaporator) and freeze-dry to obtain a stable powder. * Storage: Store the dried extract at -20°C in a sealed, light-proof container.

Workflow Visualization

Foundational Principles of Bioactivity Preservation During Purification

FAQs: Core Principles and Common Challenges

Q1: Why is bioactivity often lost during the purification of natural extracts, and what are the key factors to control?

Bioactivity loss primarily occurs due to the degradation of thermolabile compounds, irreversible adsorption to solid phases, or exposure to denaturing solvents during purification. The key factors to control are:

- Temperature: High temperatures during extraction or solvent evaporation can decompose thermolabile bioactive compounds. Methods like maceration or ultrasound-assisted extraction at controlled temperatures are often preferred for such components [23].

- Solvent Systems: The choice of solvent is critical. Solvents with a polarity value near that of the solute generally perform better. Green solvents, such as Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES), have shown promise in extracting bioactive compounds like vanillin while preserving their antioxidant and antimicrobial activities due to their non-toxic and gentle nature [24] [25].

- Extraction Duration: Prolonged extraction time does not always yield better results and can lead to degradation, especially if oxygen or light is present. The process should only continue until the equilibrium of the solute is reached inside and outside the solid material [23].

- Stationary Phase Interactions: Conventional open column chromatography with silica gel can sometimes lead to irreversible adsorption of bioactive compounds. Modern high-resolution chromatographic methods using innovative stationary phases offer better recovery [7].

Q2: How can I strategically plan a purification to minimize bioactivity loss from a complex natural extract?

A modern, strategic approach involves targeted isolation based on advanced metabolite profiling, which minimizes unnecessary purification steps and reduces the exposure of bioactive compounds to harsh conditions [7]. The workflow can be summarized as follows:

Q3: What are the best practices for solvent selection and removal to preserve antioxidant activity?

For optimal preservation of antioxidant activity:

- Selection: Alcohols (ethanol, methanol) are often considered universal solvents for phytochemicals due to their ability to effectively dissolve a wide range of phenolic compounds and antioxidants while being relatively volatile for easy removal [23]. The trend is shifting toward green solvents like NADES, which can enhance the extraction yield and stability of antioxidants [24] [26].

- Removal: Solvent removal should be performed at low temperatures using techniques like rotary evaporation under reduced pressure. For thermolabile compounds, freeze-drying (lyophilization) is a superior alternative to prevent thermal degradation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Loss of Antioxidant Activity After Chromatography

- Symptoms: A significant drop in DPPH/ABTS radical scavenging capacity or FRAP values is observed in fractions compared to the initial crude extract.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Step | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Degradation on the Stationary Phase | Analyze the initial crude extract and the flow-through from the column for bioactivity. If activity is found in the flow-through, it was not retained. If activity is lost entirely, it may have been degraded on the column. | Switch from normal-phase silica gel to a less adsorptive reversed-phase (e.g., C18) stationary phase. Consider using a support with larger pores to reduce surface interaction [7]. |

| Destructive Elution Conditions | Check the pH of the elution solvent. High or low pH can degrade sensitive phenolic compounds. | Use neutral buffer systems for elution. Avoid strong acids or bases. If ion-exchange chromatography is used, optimize the pH and ionic strength carefully to gently displace the compounds [27]. |

| Oxidation During Processing | The process was performed at room temperature over a long duration, exposed to air. | Sparge solvents with inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon). Add antioxidants like BHT to solvents where practical. Reduce processing time and perform purification at 4°C if possible. |

Problem 2: Inefficient Separation of Bioactive Analogues

- Symptoms: Bioactive compounds are co-eluted with structurally similar but unwanted analogues, leading to impure isolates and difficulty in identifying the true active principle.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Step | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Chromatographic Resolution | The purity of collected fractions is checked by analytical HPLC and shows multiple peaks. | Replace low-resolution flash chromatography with semi-preparative High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) using columns packed with smaller particles (5–10 µm). This significantly enhances resolution [7]. |

| Non-Optimized Mobile Phase | The separation was developed empirically without systematic optimization. | Use HPLC modeling software to simulate and optimize the separation. This allows for efficient method development and precise transfer from analytical to preparative scale, ensuring similar selectivity and resolution [7]. |

| Overloading the Column | The peaks are broad and asymmetric when a large amount of sample is loaded. | Use dry-loading techniques (adsorbing the sample onto a small amount of inert support) instead of injecting large volumes of solution. This sharpens the peaks and improves separation efficiency [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Bioactivity-Preserving Purification

Protocol 1: Green Extraction and Purification of Vanillin from Vanilla Pods Using NADES

This protocol exemplifies the use of environmentally friendly solvents to extract a high-value bioactive compound while preserving its antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [24] [25].

1. Objectives: To extract and purify natural vanillin from vanilla pods using a Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES), followed by the assessment of its antioxidant and antimicrobial bioactivity.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Dried Vanilla planifolia pods

- Choline chloride, 1,4-Butanediol, Lactic acid

- HPLC-grade acetonitrile and water

- SP700 resin (or equivalent non-polar resin)

- Ethanol

- DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) reagent

- Mueller-Hinton agar for antimicrobial testing

3. Equipment:

- HPLC system with UV/VIS detector and C18 column

- Ultrasonic bath

- Centrifuge

- Rotary evaporator

- pH meter

4. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- NADES Preparation: Prepare the NADES by mixing choline chloride, 1,4-butanediol, and lactic acid in a predetermined molar ratio. Stir and heat at 80°C at 400 rpm until a clear, stable liquid is formed (approx. 2-3 hours). Add 33.9% (v/v) deionized water to adjust viscosity [24].

- Sample Preparation: Cut and grind the dried vanilla pods into a fine powder (60 mesh).

- NADES Extraction: Mix the vanilla powder with the NADES at a solid-liquid ratio of 44.9 mg/mL. Perform ultrasound-assisted extraction at 64.6°C for 32.3 min. Centrifuge the suspension at 12,000 rpm for 10 min and collect the supernatant [24].

- Purification: The supernatant containing vanillin is purified by chromatography on a non-polar SP700 resin. Adjust the pH of the feed solution to 4.0 for optimal binding. Use ethanol as a desorption eluent to recover purified vanillin [24].

- Analysis: Confirm vanillin purity using HPLC and GC-MS. Assess antioxidant activity via DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays. Evaluate antimicrobial activity against a panel of food-borne bacteria using standard methods [24] [25].

5. Data Interpretation: A successful extraction should yield up to 18.5 mg of vanillin per gram of dry vanilla pod. The purified vanillin should demonstrate significant dose-dependent antioxidant activity in DPPH/ABTS assays and show clear zones of inhibition against test bacteria.

The optimization of the NADES extraction process for vanillin, as defined by Response Surface Methodology, is shown below:

Protocol 2: Targeted Isolation of Biomarkers from a Complex Extract using Analytical Profiling Transfer

This protocol details a modern approach to isolate specific, pre-identified compounds from a complex natural extract with high efficiency [7].

1. Objectives: To isolate a pure, bioactive natural product from a complex extract based on prior metabolite profiling and bioactivity data, using a transferable high-resolution chromatographic method.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Crude natural extract

- HPLC-grade solvents (water, acetonitrile, methanol)

- Semi-preparative HPLC column (e.g., C18, 5µm, 10 x 250 mm)

3. Equipment:

- UHPLC-HRMS system for profiling

- Semi-preparative HPLC system

- Fraction collector

- Evaporative Light Scattering Detector (ELSD) and/or MS detector for the semi-prep system

4. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Metabolite Profiling: First, acquire a high-resolution UHPLC-HRMS profile of the crude extract. Annotate the compounds using HRMS and MS/MS data. Correlate the chromatographic peaks with bioassay results (if available) to prioritize targets for isolation [7].

- Method Transfer: Scale up the analytical UHPLC separation method to the semi-preparative HPLC system using chromatographic calculation software. This ensures the selectivity and resolution are maintained at the larger scale [7].

- Dry Loading: Adsorb the crude extract onto a small amount of inert diatomaceous earth. Pack this dry powder into a cartridge for introduction into the HPLC system, which prevents peak broadening caused by large volume injection [7].

- Isolation with Multi-Detector Guidance: Run the semi-preparative HPLC method. Use a combination of UV, MS, and ELSD to accurately trigger the collection of the target compound(s). The ELSD and MS are particularly useful for detecting compounds with weak UV chromophores [7].

- Analysis and Purity Assessment: Analyze the collected fractions again by analytical UHPLC to confirm purity. The pure compound can then be subjected to structural elucidation (e.g., NMR) and bioactivity testing.

5. Data Interpretation: The success of this protocol is measured by the efficiency of the method transfer (similar chromatographic profile at analytical and semi-prep scales) and the final purity of the isolated compound, which should be >95% as determined by UHPLC.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for setting up bioactivity-preserving purification protocols.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Purification | Key Considerations for Bioactivity Preservation |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | Green extraction solvents composed of natural compounds (e.g., choline chloride and lactic acid). | Cost-effective, biodegradable, and non-toxic. Shown to effectively extract and preserve the bioactivity of compounds like vanillin [24] [25]. |

| Reversed-Phase C18 Silica | A versatile stationary phase for both analytical (UHPLC) and semi-preparative HPLC. | Provides high-resolution separation for a wide range of medium- to non-polar bioactive compounds. Less likely to cause irreversible adsorption compared to normal-phase silica [7]. |

| SP700 Resin | A non-polar, macroporous adsorption resin used for chromatographic purification. | Effective for purifying compounds like vanillin from NADES extracts. Its performance is optimized by controlling the pH of the feed solution [24]. |

| Evaporative Light Scattering Detector (ELSD) | A universal HPLC detector that does not rely on chromophores. | Crucial for guiding the isolation of compounds that lack UV absorption, ensuring no bioactive compound is missed during collection [7]. |

Advanced Purification Techniques: From Macroporous Resins to Green Technologies

FAQs: Core Principles and Resin Selection

Q1: What are the primary criteria for selecting a macroporous resin for purifying natural products?

The selection of an appropriate macroporous resin is a critical first step and should be based on the physicochemical properties of your target compounds and the resin's characteristics. The key criteria include:

- Polarity Matching: Resins are classified as non-polar, mid-polar, or polar. The fundamental principle is "like adsorbs like." Non-polar resins (e.g., HPD100, D101) are suitable for adsorbing non-polar compounds, mid-polar resins (e.g., AB-8) for mid-polarity compounds, and polar resins for polar compounds [28] [29].

- Pore Structure and Surface Area: The resin should have a pore diameter large enough to allow the target molecules to diffuse freely into the bead. A high specific surface area generally provides more adsorption sites [30].

- Adsorption and Desorption Capacity: The resin should not only adsorb a high quantity of the target compound but also release it efficiently during the desorption (elution) step. This is often evaluated through static adsorption/desorption tests [29] [31].

Q2: How do I screen different resins to find the best one for my specific extract?

A systematic screening protocol should be followed to compare the performance of different resins.

- Static Adsorption Test: Place a predetermined amount of pre-treated resin in a conical flask with a known volume and concentration of your sample solution. Shake thoroughly to reach adsorption equilibrium [29] [31].

- Calculate Adsorption Ratio and Capacity: Measure the concentration of the target compound in the solution before and after adsorption.

- Adsorption Ratio (%) = [(C₀ - Cₑ) / C₀] × 100%

- Adsorption Capacity (Q) = (C₀ - Cₑ) × V / W

- Where C₀ is initial concentration, Cₑ is equilibrium concentration, V is solution volume, and W is resin weight [31].

- Static Desorption Test: After adsorption, drain the solution and rinse the resin. Add a specific volume of a suitable eluent (e.g., ethanol). Shake to reach desorption equilibrium.

- Calculate Desorption Ratio: Measure the concentration of the compound in the eluent.

- Desorption Ratio (%) = [Cd × Vd / ( (C₀ - Cₑ) × V ) ] × 100%

- Where Cd is the concentration in the desorption solution and Vd is its volume [29].

The resin with the highest adsorption capacity and desorption ratio for your target compounds is typically the best choice.

Q3: Which resins are commonly used for different types of bioactive compounds?

Extensive research has identified preferred resins for various compound classes. The table below summarizes some well-documented examples.

| Target Compound | Recommended Resin(s) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Stilbene Glycoside (from Polygonum multiflorum) | HPD100 | Under optimized conditions, achieved a final product content of 819 mg/g and a recovery yield of 74.7% [28]. |

| Flavonoids & Ginkgolides (from Ginkgo biloba leaves) | DA-201 | Successfully enriched total flavonoids to 25.36% and ginkgolides to 12.43% in the final dry extract [32]. |

| Various Saponins (from Astragalus) | AB-8 | Showed superior recovery rates (82%-99%) for multiple astragalosides and isoastragalosides compared to other tested resins [29]. |

| Polyphenols (from Areca Seeds) | XAD-7 | Provided the best adsorption/desorption performance and the resulting products exhibited strong antioxidant activity [31]. |

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

Q4: My target compounds are not being effectively adsorbed by the resin. What could be wrong?

This is a common issue often related to the sample solution properties or the resin itself.

- Cause 1: Incorrect Polarity Matching. The resin's polarity may not be suitable for your target compounds.

- Solution: Re-screen resins with different polarities using the static adsorption test described above [29].

- Cause 2: Suboptimal Sample Solution Conditions. The pH, concentration, or ionic strength of your sample can drastically affect adsorption.

- Cause 3: Resin Saturation or Fouling.

- Solution: Ensure the resin has been properly regenerated before use. If the resin is old or fouled by irreversible adsorption of impurities, it may need to be replaced.

Q5: The adsorption capacity is good, but my recovery during elution is low. How can I improve this?

Poor desorption typically points to issues with the elution solvent or process.

- Cause 1: Inadequate Elution Solvent. The solvent's type, concentration, or volume may be insufficient to overcome the adsorption forces.

- Solution: Optimize the eluent. Ethanol-water mixtures are common. Test different concentrations (e.g., 50%, 70%, 90% ethanol) to find the one that maximizes desorption yield without co-eluting too many impurities [28] [31]. Increasing the volume of eluent can also help, but an optimum exists before dilution becomes a problem [29].

- Cause 2: Too Fast Flow Rate. A high flow rate during dynamic desorption does not allow sufficient contact time for the eluent to diffuse into the resin pores and displace the target compounds.

Optimization Parameters and Methodologies

Q6: What are the key parameters to optimize in a macroporous resin purification process?

Once a resin is selected, the operational conditions must be systematically optimized. The most critical parameters are:

- Sample Loading Conditions: pH, concentration, and flow rate.

- Washing Conditions: Volume and composition of wash solvent to remove weakly adsorbed impurities.

- Elution Conditions: Eluent concentration (e.g., ethanol %), volume, and flow rate.

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to process optimization, from single-factor experiments to advanced statistical design.

Q7: How can I efficiently optimize multiple parameters at once?

The traditional "one-factor-at-a-time" approach is inefficient and fails to reveal interactions between factors. The recommended methodology is a combination of statistical designs:

- Plackett-Burman Design (PBD): This is a screening design used to identify which factors from a large set have a significant impact on your response (e.g., recovery yield, purity). It requires a relatively small number of experimental runs [29] [32].

- Response Surface Methodology (RSM): After identifying the key factors (typically 2-4) with PBD, RSM is used to find their optimal levels. A Central Composite Design (CCD) is commonly used to build a quadratic model that maps the relationship between the factors and the response, allowing you to pinpoint the precise optimum [29].

Q8: How do I handle the optimization of multiple target components with different properties?

When purifying a multi-component extract, you must define a comprehensive evaluation index. The Entropy Weight Method (EWM) is an objective and powerful technique for this purpose.

- Procedure:

- You obtain the recovery data for all your target components from your experiments.

- EWM calculates a weight for each component based on the variability of its recovery data across different experiments. A component with a large variation provides more information and is assigned a higher weight.

- A comprehensive score (Z) is calculated as the sum of each component's recovery multiplied by its entropy weight.

- Application: This comprehensive score (Z) becomes the single response variable you use in your PBD and RSM optimization, ensuring the process is balanced for all important components [29].

The table below summarizes the optimized parameters from several published studies as reference examples.

| Purification Target | Resin | Optimal Parameters | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stilbene Glycoside [28] | HPD100 | Sample conc.: 3.5 mg/mL; pH: 4.8; Eluent: 40% Ethanol; Flow rate: 1.5 mL/min | Recovery: 74.7%; Purity: 81.9% |

| Astragalus Saponins [29] | AB-8 | pH: 6.0; Sample conc.: 0.15 g/mL; Eluent: 75% Ethanol | High comprehensive score for 7 saponins |

| Areca Seed Polyphenols [31] | XAD-7 | Sample conc.: 3.0 mg/mL; pH: 3.0; Eluent: 50% Ethanol; Flow rate: 2 BV/h | High purity and antioxidant activity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| AB-8 Macroporous Resin | A mid-polar resin highly effective for purifying various flavonoids and saponins [29]. |

| HPD100 Macroporous Resin | A non-polar resin successfully used for the purification of stilbene glycosides and other compounds [28]. |

| DA-201 Macroporous Resin | Used for the simultaneous enrichment of flavonoids and ginkgolides from complex plant extracts [32]. |

| XAD-7 Macroporous Resin | A resin noted for its excellent performance in purifying polyphenols with strong antioxidant activity [31]. |

| Ethanol (Aqueous Solutions) | The most common elution solvent due to its effectiveness, low cost, and low toxicity. The optimal concentration (e.g., 40%-75%) is compound-dependent [28] [29] [31]. |

| Formic Acid / HCl / NaOH | Used to adjust the pH of the sample solution, which is critical for controlling the ionization state of target compounds and thus their adsorption behavior [28] [29] [31]. |

| UPLC/HPLC-DAD-MS | The essential analytical tool for identifying and quantifying target compounds in crude extracts and purified fractions during screening and optimization [33] [32]. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dynamic Adsorption and Desorption in a Packed Column

This protocol is used for scaling up and final process validation after initial static tests [28].

- Resin Preparation: Pack a glass column with a known volume of pre-treated and equilibrated resin.

- Sample Loading: Pass the sample solution through the column at a controlled flow rate (e.g., 1-2 BV/h). Collect the effluent and analyze to determine the breakthrough point and dynamic adsorption capacity.

- Washing: After loading, wash the column with 2-4 bed volumes (BV) of deionized water to remove unadsorbed impurities.

- Elution: Elute the target compounds using the optimized eluent (e.g., 50-75% ethanol) at a controlled flow rate. Collect the eluate in fractions.

- Analysis: Analyze the fractions to pool those rich in your target compounds. Concentrate and dry to obtain the purified product.

Protocol 2: Multi-Response Optimization using EWM and Statistical Design

This integrated protocol is ideal for complex natural extracts [29].

- Single-Factor Experiments: Conduct preliminary tests to determine the approximate range for each factor (pH, concentration, flow rate, eluent %, etc.).

- Plackett-Burman Design: Design and run a PBD experiment using the factors and ranges from step 1. The response is the comprehensive score (Z) calculated via EWM from the recoveries of all target compounds.

- Statistical Analysis: Analyze the PBD results to identify the significant factors.

- Central Composite Design: Design and run a CCD focusing on the significant factors (e.g., 2-3 factors). The response is again the comprehensive score (Z).

- Modeling and Prediction: Use statistical software to generate a quadratic regression model from the CCD data and predict the optimal parameter values.

- Verification: Perform a verification experiment under the predicted optimal conditions to confirm that the practical results match the predictions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Resolution | Incorrect pore size for target protein [34], column degradation [35], excessive flow rate [34] | - Check calibration curve match for analyte MW [34]- Use smaller particle size columns (e.g., <3 µm) for higher efficiency [34]- Reduce flow rate to improve efficiency [34] |

| Abnormal Retention Times | Chemical interactions with stationary phase [34], mobile phase composition error [34] | - Adjust mobile phase ionic strength/pH to minimize unwanted interactions [34]- Ensure mobile phase is consistent and degassed [34] |

| High Backpressure | Column frit blockage [35], contaminated column [35] | - Inspect and clean or replace inlet frit [35]- Filter samples and mobile phases [35]- Replace column if severely contaminated [35] |

| Low Protein Recovery | Non-specific adsorption to stationary phase [34], protein aggregation [36] | - Add moderate salt (e.g., 150-200 mM NaCl) to mobile phase [34]- Screen small-scale purification protocols to identify optimal conditions [36] |

Adsorption Chromatography Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Recovery/Purity | Insufficient elution strength [37], inappropriate elution volume [37], fouled adsorbent [37] | - Optimize elution strength and volume; measure recovery via mass balance [37]- Implement regular adsorbent regeneration (thermal, chemical) [37] |

| Peak Tailing/Broadening | Mass transfer limitations [37], heterogeneous adsorbent surface [38] | - Optimize flow rate, temperature, contact time to enhance kinetics [37]- Use high-quality solvents for consistent mobile phase strength [38] |

| Loss of Adsorbent Activity | Adsorbent poisoning, fouling, or thermal degradation [37] | - Monitor performance with breakthrough curves and pressure drop measurements [37]- Determine optimal regeneration method and frequency [37] |

| Direct Processing Challenges | Column blockage from particulate feedstocks [39] | - Use expanded bed adsorption to process particulate-containing feeds directly [39] |

Partition Chromatography Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions | | :--- | :--- | : Solutions | | Poor Separation/Resolution | Incorrect stationary/mobile phase selection [40] [38], poor column packing [37] | - Normal-phase: Use polar stationary phase (cyano, amino) with nonpolar→polar solvent gradient [40]- Reversed-phase (RPLC): Use nonpolar stationary phase (C8, C18) with polar mobile phase (water→organic) [40] | | Inadequate Recovery/Purity | Adsorption losses, peak splitting, contamination [37] | - Optimize elution strength and fraction collection size [37]- Ensure adequate cleaning of column and equipment [37] | | Retention Time Drift (HILIC) | Unstable water-enriched layer on support [40] | - Pre-equilibrate column with mobile phase to establish consistent water-enriched layer [40] | | Low Yield in CPC | Suboptimal solvent system or operating conditions [41] | - Optimize biphasic solvent system (e.g., Hexane/Butanol/Ethanol/Water) [41]- Optimize flow rate and rotation speed (e.g., 8 mL/min, 1600 rpm) [41] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose the correct SEC column for my protein? The choice depends on the molecular weight of your target protein. For most therapeutic proteins (15-80 kDa), a pore size of 150-200 Å is suitable. For monoclonal antibodies (~150 kDa), a 200-300 Å pore size is recommended, and for very large proteins (>200 kDa), 500-1000 Å materials are appropriate [34]. The particle size also matters; smaller particles (<3 µm) in shorter columns (e.g., 15 cm) can provide higher resolution or faster analysis [34].

Q2: What are the critical factors for successfully scaling up adsorption chromatography? For scalable adsorption chromatography, especially with complex feeds like natural extracts, factors critical to success include the correct choice of adsorbent and careful apparatus design [39]. The optimization and scale-up of operating protocols for expanded-bed procedures are very similar to those for packed beds [39]. Regularly monitor adsorbent performance and regeneration efficiency [37].

Q3: My reversed-phase separation of a natural extract shows poor peak shape. What should I check? First, check the mobile phase composition and pH, as these greatly affect retention and selectivity in RPLC [40]. Ensure your sample is compatible with the mobile phase to avoid precipitation. Also, consider the chemistry of your analyte; RPLC is ideal for separating a broad range of substances in aqueous samples [40].

Q4: How can I quickly screen conditions to optimize a protein purification protocol? Coupling small-scale expression with mini-size exclusion chromatography is an effective screening approach [36]. Using miniature SEC columns allows you to analyze aggregation and identify low-mass contaminants with very small sample volumes (e.g., 35 µL of eluate) and short cycle times (under 30 minutes), helping you identify optimal conditions for large-scale production [36].

Q5: What is a key advantage of Centrifugal Partition Chromatography (CPC) for isolating natural products? CPC is a solid-support-free liquid-liquid partition chromatography technique that eliminates irreversible adsorption, making it highly effective for the preparative-scale isolation of high-purity compounds directly from crude extracts [41]. Its optimized protocols can be selective for specific compounds, such as magnoflorine and berberine from Berberis vulgaris, and are easy to commercialize [41].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

This protocol is designed to identify the optimal growth and purification conditions for large-scale protein production by coupling affinity purification with size-exclusion analysis.

1. Small-Scale Expression and Affinity Purification:

- Express the target protein in a small-scale culture (e.g., 1-10 mL).

- Lyse the cells using your preferred method (e.g., sonication, enzymatic lysis).

- Clarify the lysate by centrifugation to remove cellular debris.

- Incubate the supernatant with magnetic beads functionalized with the appropriate affinity ligand (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins, antibody-coated beads for specific antigens).

- Wash the beads thoroughly with a suitable buffer to remove non-specifically bound contaminants.

- Elute the bound protein using a specific elution buffer (e.g., imidazole for His-tagged proteins, low pH, or competitive ligand). The typical elution volume can be as small as 35 µL.

2. Mini-Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Analysis:

- Equilibrate a mini-SEC column with your desired mobile phase (e.g., PBS or Tris buffer).

- Load the entire 35 µL of the affinity eluate onto the column.

- Run the SEC isocratically at a recommended flow rate. The entire cycle, including washing and re-equilibration, can be completed within 30 minutes.

- Monitor the eluent at 280 nm (or other relevant wavelengths) to obtain the chromatogram.

3. Data Analysis:

- The SEC chromatogram completes the SDS-PAGE analysis by estimating the amount of soluble aggregates in the elution fraction and identifying low molecular mass contaminants that might co-migrate in a gel [36].

- Compare results from different growth and purification conditions to select the protocol that yields the highest amount of monodisperse, pure protein for scale-up.

This detailed protocol is optimized for the isolation of magnoflorine and berberine from Berberis vulgaris extracts, demonstrating the application of partition chromatography for complex natural extracts.

1. Plant Material Extraction:

- Obtain dried and powdered plant material (e.g., root or stem of Berberis vulgaris).

- Perform pressurized liquid extraction (e.g., using an Accelerated Solvent Extractor) with methanol as the solvent. Conditions: static time 10 min, 4 cycles, temperature 90°C, pressure 96 bar.

- Combine the extracts from all cycles and evaporate to dryness using a rotary evaporator at 45°C.

- Weigh the dried extract and store at 4°C until use.

2. CPC Separation:

- Solvent System Preparation: Prepare a biphasic solvent system consisting of Hexane/Butanol/Ethanol/Water in a volume ratio of 3:12:4:16. Allow the mixture to equilibrate in a separation funnel, then separate the upper (organic) and lower (aqueous) phases.

- Sample Solution Preparation: Dissolve the dry extract in a 1:1 mixture of the upper and lower phases of the solvent system.

- CPC Instrument Setup:

- Fill the CPC column with the stationary phase (the upper organic phase).

- Set the instrument to the ascending mode (mobile phase is the lower aqueous phase).

- Set the rotation speed to 1600 rpm and the mobile phase flow rate to 8 mL/min.

- Separation Run:

- Inject the sample solution into the CPC system.

- Collect the eluent in fractions based on time or automated peak detection.

- Fraction Analysis: Analyze the collected fractions by Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) or HPLC to identify those containing the target compounds (magnoflorine and berberine).

- Fraction Combination and Evaporation: Combine the pure fractions for each alkaloid and evaporate the solvent to obtain the isolated compounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Silica-based SEC Particles | Porous particles for separating biomolecules by size; choose pore size (150-500 Å) based on target protein molecular weight [34]. |

| Magnetic Affinity Beads | For rapid, small-scale affinity purification prior to SEC analysis; enable parallel processing of multiple conditions [36]. |

| Polar Adsorbents (Silica, Alumina) | Stationary phases for adsorption chromatography; retain polar compounds from non-polar solvents, useful for steroids, isomers [38]. |

| Bonded Phase Silicas (C8, C18, Diol) | Chemically bonded stationary phases for partition chromatography; C8/C18 for reversed-phase, cyano/amino/diol for normal-phase [40]. |

| Biphasic Solvent Systems | Immiscible solvent pairs (e.g., Hexane/Butanol/Ethanol/Water) used as mobile/stationary phases in Centrifugal Partition Chromatography (CPC) [41]. |

| Pre-column Filters | Protect analytical columns from particulate matter in samples or mobile phases, preventing blockages and high backpressure [35]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common NADES Experimental Issues and Solutions

Problem: High Viscosity Leading to Poor Extraction Efficiency

High viscosity is a common challenge with many NADES, as it can hinder mass transfer during extraction and lead to inefficient processes [42]. The table below summarizes the causes and solutions for this issue.

Table: Troubleshooting High Viscosity in NADES

| Cause | Effect on Experiment | Solution | Supporting Data/ Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inherently high viscosity of the NADES [42] | Reduced mass transfer; low extraction yield of target compounds. | Dilute the NADES with a moderate amount of water [43] [42]. | A study using Citric Acid:1,2-Propanediol (CAPD 1:4) successfully used water to reduce viscosity, improving extraction [43]. |

| Incorrect temperature setting | Viscosity remains too high for efficient mixing and solute dissolution. | Optimize and increase the extraction temperature [43]. | An optimized protocol for poplar propolis used a temperature of 65°C to achieve high phenolic content [43]. |

| Suboptimal component ratio | The solvent does not achieve its lowest possible melting point or ideal physicochemical properties. | Re-synthesize the NADES, ensuring precise molar ratios of components. | The properties of NADES depend heavily on the intermolecular interactions between components, which are influenced by their ratios [44]. |

Problem: Precipitation of Extracted Compounds or NADES Components

Table: Troubleshooting Precipitation in NADES Systems

| Cause | Effect on Experiment | Solution | Supporting Data/ Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water content is too low | Some NADES components or extracted compounds may crystallize out of solution. | Increase the water content slightly to stabilize the mixture. | Water plays a major role in NADES formation and can significantly influence their solvating properties and stability [42]. |

| The extracted compound is insoluble in the selected NADES | The target compound precipitates after extraction or during storage, leading to low recovery. | Screen a different NADES with a polarity better matched to your target compound. | NADES can be tailored to have a broad range of polarities, from hydrophilic to lipophilic [42]. |

| Temperature fluctuation | Components of the NADES or the solutes crash out of solution upon cooling. | Ensure a consistent, appropriate temperature is maintained during the entire process. | The eutectic state is a thermodynamic balance that can be influenced by temperature, potentially leading to dissociation of the mixture [44]. |

Problem: Low Extraction Yield of Target Bioactive Compound

Table: Troubleshooting Low Extraction Yield with NADES

| Cause | Effect on Experiment | Solution | Supporting Data/ Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inefficient mass transfer | The target compound is not fully liberated from the solid matrix. | Incorporate auxiliary energy techniques like ultrasonication [43]. | Ultrasonic extraction was successfully optimized for poplar propolis, maximizing total phenolic content [43]. |

| Incorrect solid-to-solvent ratio | The system is either too diluted or too saturated for efficient transfer of the solute. | Systematically optimize the solvent-to-solid ratio [43]. | A ratio of 30 mL/g was identified as a key optimal parameter for extracting phenolics from propolis [43]. |

| Wrong NADES type selected | The solvent's properties (e.g., polarity, hydrogen bonding capacity) are not suitable for the target molecule. | Perform a screening of different NADES compositions (e.g., choline chloride-based, organic acid-based). | Research shows that the extraction efficiency varies significantly with NADES composition. For example, betaine:malic acid:proline and choline chloride:propylene glycol have been identified as effective for different propolis types [43]. |

Advanced Troubleshooting Protocol

This protocol provides a systematic approach for resolving persistent or complex issues, based on general scientific troubleshooting principles.

Step 1: Repeat the Experiment

- Unless cost or time prohibitive, always repeat the experiment to rule out simple human error, such as incorrect measurement of components or improper mixing [45].

Step 2: Validate the Experimental Premise

- Revisit the scientific literature. Consider if there is another plausible reason for your results. A negative result might not indicate a failed protocol but could reveal a new biological insight (e.g., the target compound may not be present in your specific sample at detectable levels) [45].

Step 3: Implement Appropriate Controls

- Include a positive control (e.g., a known source where the target compound is abundant) to confirm your protocol works.

- Include a negative control to identify false positives [45].

- If the positive control fails, the problem lies with the protocol or reagents.

Step 4: Audit Equipment and Materials

- Check for improper storage of reagents (e.g., temperature sensitivity) [45].

- Verify the compatibility of all materials (e.g., are the NADES components and extraction matrix chemically compatible?).

- Inspect reagents visually for signs of degradation, such as cloudiness in normally clear solutions [45].

Step 5: Systematically Change Variables

- Generate a list of potential variables (e.g., NADES water content, extraction time, temperature, ultrasound power).

- Change only one variable at a time (OFAT) to isolate the root cause [45].

- Document every change and outcome meticulously in a lab notebook [45].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly are Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) and how do they differ from Ionic Liquids (ILs) and conventional solvents?

A: NADES are a new class of green solvents composed of natural primary metabolites, such as organic acids, sugars, sugar alcohols, and amino acids [44] [42]. When mixed in specific molar ratios, these components form a liquid eutectic mixture with a melting point lower than that of each individual component, primarily through hydrogen bonding interactions [46] [44].

The key differences are summarized below:

- vs. Conventional Organic Solvents: Unlike volatile, flammable, and often toxic organic solvents (e.g., hexane, methanol), NADES are characterized by negligible vapor pressure, non-flammability, low toxicity, and high biodegradability [44] [42] [47].

- vs. Ionic Liquids (ILs): While both are considered "green" solvents with low volatility, ILs consist entirely of ions and are held together by ionic bonds. NADES are not necessarily ionic; they are mixtures of molecular components held by hydrogen bonds. This makes NADES typically cheaper, easier to synthesize (no purification needed), and often more biodegradable and less toxic than many ILs [46] [44].

Q2: I'm new to the field. Which NADES would you recommend I start with for extracting phenolic compounds from plant material?

A: A good starting point for extracting phenolic compounds is to use NADES based on choline chloride (ChCl) or organic acids [43]. Specifically, the following have shown high efficiency in scientific literature:

- ChCl:Urea (1:2 molar ratio)

- ChCl:Glycerol (1:2)

- Citric Acid:1,2-Propanediol (1:4) [43]

- ChCl:Lactic Acid (1:2)

These solvents have demonstrated a strong ability to solubilize and stabilize a wide range of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and other polar bioactive molecules [43] [42] [47].