Molecular Networking for Metabolite Annotation: Advanced Strategies for Researchers and Drug Development

Molecular networking has emerged as a cornerstone methodology for metabolite annotation in untargeted metabolomics, transforming complex MS/MS data into intuitive molecular relationship maps.

Molecular Networking for Metabolite Annotation: Advanced Strategies for Researchers and Drug Development

Abstract

Molecular networking has emerged as a cornerstone methodology for metabolite annotation in untargeted metabolomics, transforming complex MS/MS data into intuitive molecular relationship maps. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering foundational principles to cutting-edge advancements. We explore core concepts like data-driven (e.g., GNPS, FBMN) and knowledge-driven networks (e.g., MetDNA3), detail practical workflows and platform selection, address critical troubleshooting for issues like matrix effects and low-abundance metabolites, and validate strategies through performance metrics and real-world case studies across natural products and clinical biospecimens. The content synthesizes the latest research, including interactive two-layer networking, multiplexed chemical metabolomics (MCheM), and AI integration, offering a roadmap to enhance annotation coverage, accuracy, and efficiency in biomedical research.

Understanding Molecular Networking: Core Principles and Evolving Landscape

Molecular networking has emerged as a cornerstone strategy in untargeted metabolomics, transforming spectral data into structural insights for metabolite annotation. This approach operates on the fundamental principle that similar fragmentation spectra often indicate similar molecular structures, enabling researchers to navigate the vast chemical space of metabolites beyond the constraints of reference libraries [1]. By translating mass spectrometry data into connected networks, this methodology allows for the systematic annotation of unknown metabolites through their spectral relationships to known compounds.

The field has evolved into two complementary paradigms: data-driven networking, which discovers latent spectral relationships, and knowledge-driven networking, which leverages established biochemical knowledge [2]. Recent advancements, such as the two-layer interactive networking topology implemented in MetDNA3, integrate these approaches to achieve unprecedented annotation coverage and accuracy [2]. This protocol details the practical application of these principles, providing researchers with methodologies to advance metabolite discovery in complex biological systems.

Quantitative Data on Molecular Networking Performance

The performance of molecular networking strategies can be evaluated through several key metrics, including annotation coverage, accuracy, and computational efficiency. The tables below summarize quantitative data from recent studies and algorithmic parameters.

Table 1: Annotation Performance of Advanced Networking Strategies

| Method / Platform | Annotation Coverage | Annotation Accuracy | Number of Annotated Metabolites | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MetDNA3 (Two-layer networking) | Not explicitly stated | Not explicitly stated | >1,600 seed metabolites & >12,000 via propagation [2] | 10-fold improvement [2] |

| E-SGMN with Astral MS | 76.84% (spiked plasma) [3] | 78.08% (spiked plasma) [3] | 5,440 features from NIST SRM 1950 plasma (3.6x increase) [3] | Not specified |

| SODA-MN | Not specified | Not specified | 48 polyphenol derivatives (1st round) [1] | Not specified |

Table 2: Key Algorithmic Parameters for Spectral Similarity Measurement

| Algorithm | Key Principle | Applicable Data | Critical Parameters | Typical Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Cosine | Aligns spectra by fragment m/z or neutral loss mass differences [4] | LC-MS/MS | m/z tolerance, minimum matched signals, intensity filters [4] | Minimum cosine >0.6-0.7 [4] |

| MS2DeepScore | Deep neural network predicts structural similarity from spectra [4] | LC-MS/MS | Pre-trained model, minimum number of signals [4] | Minimum similarity >0.8 [4] |

| Classical Cosine | Groups features based on spectral pattern similarity [4] | GC/EI-MS | m/z tolerance, intensity filters [4] | Not specified |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Two-Layer Interactive Networking with MetDNA3

This protocol describes the procedure for implementing the two-layer interactive networking topology as implemented in MetDNA3, which integrates data-driven and knowledge-driven networks for recursive metabolite annotation [2].

I. Curate the Metabolic Reaction Network (Knowledge Layer)

- Step 1: Retrieve metabolite reaction pairs from knowledge databases (e.g., KEGG, MetaCyc, HMDB) with and without known reaction relationships.

- Step 2: Train a graph neural network (GNN) model to learn reaction rules from known reactant pairs and predict potential relationships between structurally similar metabolite pairs [2].

- Step 3: Apply a two-step pre-screening strategy to control potential false positives in predicted reaction pairs.

- Step 4: Enhance metabolite coverage by generating unknown metabolites using tools like BioTransformer [2].

- Step 5: Construct the comprehensive Metabolic Reaction Network (MRN) comprising the integrated and expanded metabolites and reaction pairs.

II. Pre-map Experimental Data to Establish Two-Layer Topology

- Step 1: Perform sequential MS1 m/z matching to map experimental features to metabolites in the MRN, forming an MS1-constrained MRN [2].

- Step 2: Map reaction relationships from this constrained MRN onto the experimental data layer to guide the construction of a feature network.

- Step 3: Calculate MS2 spectral similarity between experimental features and apply it as a constraint to filter nodes, refining the structure into a knowledge-constrained feature network.

- Step 4: Map the topological connectivity of this refined feature network back to the knowledge layer, resulting in a data-constrained MRN. This finalizes the two-layer topology with consistent metabolite-feature relationships [2].

III. Execute Recursive Metabolite Annotation Propagation

- Step 1: Begin with "seed" metabolites confidently identified by matching to authentic chemical standards.

- Step 2: Leverage the established cross-network interactions between the data and knowledge layers.

- Step 3: Propagate annotations recursively from seed metabolites to unknown features connected within the network based on reaction relationships and high MS2 spectral similarity [2].

Protocol: Standard-Oriented/Database-Assisted Molecular Networking (SODA-MN)

This protocol is designed for the iterative annotation of specific metabolite classes, such as polyphenols and their gut bacterial biotransformation products [1].

I. Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition

- Step 1: Treat biological samples (e.g., gut bacterial cultures) with the compound of interest (e.g., Black Raspberry Extract) and include appropriate controls [1].

- Step 2: Harvest samples at relevant time points (e.g., for time-course studies).

- Step 3: Extract metabolites using appropriate solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate with 1% formic acid). Combine organic layers from repeated extractions and dry under a vacuum [1].

- Step 4: Reconstitute dried samples in a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol) for LC-MS analysis.

- Step 5: Acquire LC-MS/MS data using a UPLC system coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer with a data-dependent acquisition (DDA) method [1].

II. Data Pre-processing and Molecular Network Construction

- Step 1: Process raw LC-MS/MS data using software (e.g., MZmine) for feature detection, alignment, and MS/MS spectra extraction.

- Step 2: Create a molecular network using a platform like GNPS or the implemented SODA-MN method. Use parameters such as a minimum matched fragment of 5 and a minimum cosine similarity score of 0.5 for the initial analysis [1].

III. Iterative, Seed-Driven Annotation

- Step 1: Use detected standard compounds ("seeds") as starting points within the network.

- Step 2: Annotate derivatives by searching for network connections that represent the addition or deduction of common biotransformation groups (e.g., hydroxylation, methylation, sulfation) [1].

- Step 3: Iteratively use newly annotated compounds as seeds for the next round of annotation, progressively expanding the annotation coverage within the complex metabolic profile.

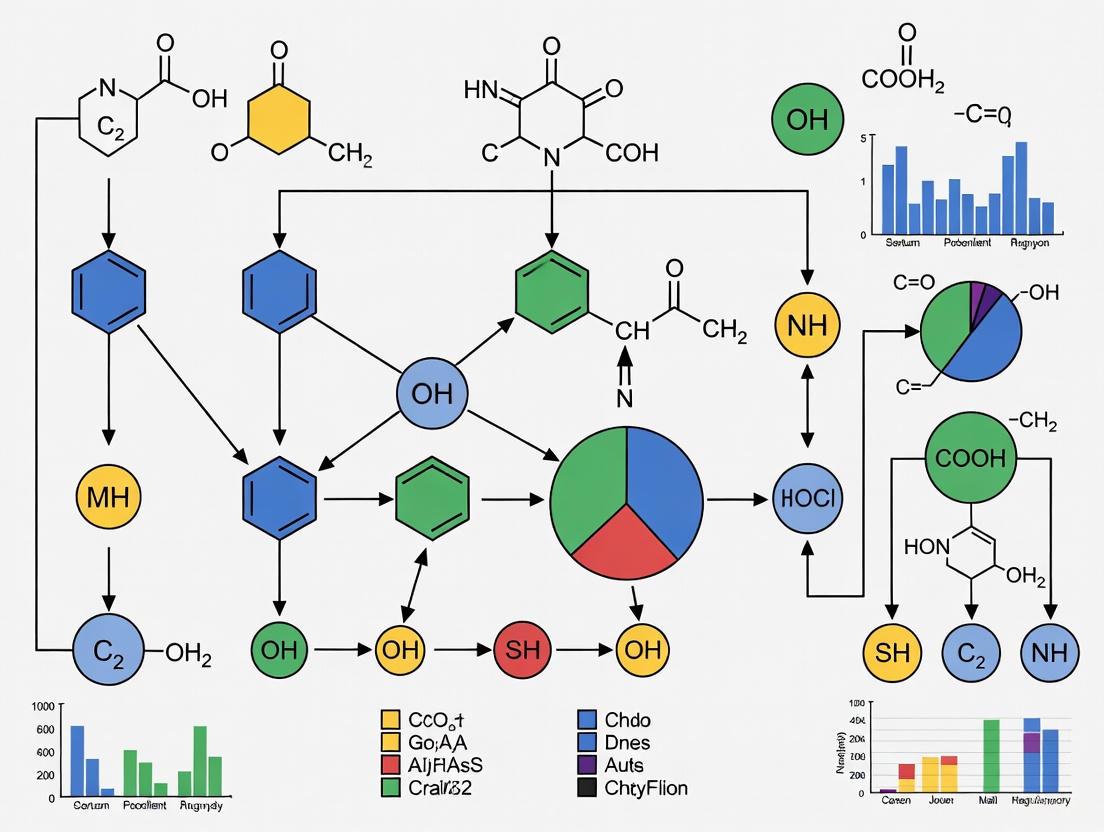

Workflow Visualization

Molecular Networking Workflow

MetDNA3 Two-Layer Topology

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents, Tools, and Databases

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Gifu Anaerobic Broth (GAM) | Culture medium for growing gut bacteria under anaerobic conditions for metabolic studies [1]. | Procured from Fisher Scientific or HiMedia Laboratories [1]. |

| Authentic Chemical Standards | Serve as "seed" compounds for initial confident identification and propagation in molecular networks [1]. | Commercial providers (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich, BerriHealth for Black Raspberry Extract) [1]. |

| Global Standard Reference Extracts | Quality control samples to monitor instrument performance and enable cross-dataset comparisons [5]. | Aliquots of a well-characterized biological extract (e.g., from Arabidopsis Columbia-0 plants) [5]. |

| Metabolic Knowledge Databases | Provide the known metabolite and reaction relationships for knowledge-driven networking. | KEGG, MetaCyc, HMDB [2]. |

| BioTransformer Tool | Computational tool to predict potential microbial and human metabolites, expanding network coverage [2]. | Freely available software for metabolite prediction [2]. |

| MetDNA3 Platform | Implements the two-layer interactive networking topology for recursive metabolite annotation. | Freely available at http://metdna.zhulab.cn/ [2]. |

Contrasting Data-Driven and Knowledge-Driven Networking Approaches

Molecular networking has revolutionized metabolite annotation in untargeted metabolomics by enabling the systematic organization and interpretation of complex mass spectrometry data. The field is primarily dominated by two complementary paradigms: data-driven approaches, which uncover latent relationships from experimental data without prior assumptions, and knowledge-driven approaches, which leverage established biochemical knowledge to guide annotation. This application note provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, detailing their fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and applications in natural product discovery and drug development. We present standardized workflows for implementing both strategies, quantitative performance comparisons, and visualization of their integrative potential. For researchers in pharmaceutical and metabolomics fields, this resource offers practical guidance for selecting and implementing appropriate networking strategies to enhance metabolite annotation coverage, accuracy, and efficiency in their research programs.

Metabolite annotation remains a significant challenge in untargeted metabolomics due to the vast structural diversity of metabolites and limitations in available chemical standards. Molecular networking has emerged as a powerful computational strategy to address this challenge by visualizing complex mass spectrometry data as relational networks [6]. These approaches can be broadly categorized into data-driven and knowledge-driven methodologies, each with distinct strengths and applications.

Data-driven networking employs unsupervised modeling to uncover latent associations among experimental features based on relationships such as MS2 spectral similarity, mass differences, and intensity correlation [2]. This approach requires no prior biochemical knowledge and excels at discovering novel metabolites and structural relationships. In contrast, knowledge-driven networking utilizes supervised modeling that integrates established biochemical knowledge—such as metabolic reactions and pathways—with experimental data to enable targeted metabolite annotation [2]. This method provides high-confidence annotations for known biochemical transformations but is constrained by the coverage of existing metabolite databases.

The integration of these approaches represents the cutting edge of metabolite annotation research. As noted in Nature Communications (2025), "Combining data-driven and knowledge-driven networks for metabolite annotation leverages the strengths of both approaches, improving annotation accuracy and coverage" [2]. This application note details the protocols, applications, and implementation strategies for both approaches within the context of advanced metabolite annotation research.

Comparative Analysis of Networking Approaches

Data-Driven Networking: Principles and Applications

Data-driven networking constructs relationships directly from experimental mass spectrometry data without incorporating prior biochemical knowledge. The foundational technique is molecular networking (MN), initially developed through the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform [6]. In this approach, nodes represent MS/MS features, while edges denote spectral similarity, effectively clustering compounds with analogous fragmentation patterns into molecular families [7].

Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN) represents an advanced evolution that incorporates chromatographic information to discriminate between isomers and incorporate quantitative data into network visualizations [7]. This technique has proven particularly valuable in natural product research, where it enables "the discovery of novel ascorbic acid derivatives and other metabolites" through untargeted metabolomics [6]. The approach has demonstrated exceptional utility in profiling complex natural product mixtures, such as annotating 69 flavonoid glycosides from Quercus mongolica bee pollen, primarily comprising kaempferol, quercetin, and isorhamnetin derivatives [8].

Table 1: Data-Driven Molecular Networking Tools and Applications

| Tool Name | Core Functionality | Advantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MN [6] | Groups compounds by MS2 spectral similarity | Intuitive visualization of chemical space; No prior knowledge required | Initial exploration of complex samples; Natural product discovery |

| Feature-Based MN (FBMN) [7] | Incorporates chromatographic data & quantitative features | Discriminates isomers; Includes quantitative information | Comparative metabolomics; Flavonoid diversity studies [8] |

| Ion Identity MN (IIMN) [6] | Consolidates different ion species of same molecule | Reduces data redundancy; Optimizes network complexity | Comprehensive metabolite profiling |

| Bioactive MN (BMN) [6] | Integrates bioactivity data with spectral networks | Links chemical features to biological activity | Bioactive compound discovery |

| LC-MS/MS Data Processing | Converts raw data to mzXML/mzML/MGF formats | Enables platform-independent analysis | Data standardization for GNPS |

Knowledge-Driven Networking: Principles and Applications

Knowledge-driven networking employs curated biochemical knowledge to guide the annotation process. This approach constructs networks where nodes represent known metabolites and edges define established relationships, such as metabolic reactions or structural similarities [2]. Unlike data-driven methods, knowledge-driven networking leverages existing biological knowledge to make inferences about unknown metabolites.

The Metabolic Reaction Network (MRN) is a prominent example that uses known biochemical transformations to facilitate annotation propagation. As reported in Nature Communications, advanced implementations like MetDNA3 employ graph neural network (GNN)-based prediction to dramatically expand reaction network coverage, resulting in "a total of 765,755 metabolites and 2,437,884 potential reaction pairs" compared to sparser traditional knowledge bases [2]. This expanded coverage addresses a fundamental limitation of earlier knowledge-driven approaches while maintaining biological relevance.

Key advantages of knowledge-driven networking include higher confidence annotations for known biochemical pathways and more efficient annotation propagation through established metabolic relationships. The structured nature of these networks also provides inherent validation through biochemical consistency, making them particularly valuable for studying defined metabolic pathways in model organisms or human metabolism.

Table 2: Knowledge-Driven Networking Approaches

| Approach | Knowledge Source | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Reaction Network (MRN) [2] | KEGG, MetaCyc, HMDB | Uses known biochemical transformations; High-confidence annotations | Limited to known metabolism; Sparse connectivity in basic implementations |

| Expanded MRN with GNN [2] | Multiple databases + prediction | 765,755 metabolites; 2,437,884 reaction pairs; Enhanced connectivity | Potential false positives from predictions |

| Reaction Relationship Mapping [2] | Biochemical reaction rules | Enables recursive annotation; Covers knowns and predicted unknowns | Dependent on quality of reaction rules |

| Structural Similarity Networks [2] | Chemical structure databases | Tanimoto coefficient-based relationships; Structure-focused annotation | May miss biochemical context |

Experimental Protocols

Data-Driven Networking Protocol: Feature-Based Molecular Networking

Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition

- Extract metabolites from biological samples using appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol:water 80:20 for polar metabolites, dichloromethane:methanol for lipids).

- Perform LC-MS/MS analysis using reversed-phase or HILIC chromatography coupled to high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry.

- Employ data-dependent acquisition (DDA) with dynamic exclusion to maximize MS/MS coverage [6]. Key parameters: MS1 resolution >60,000, MS2 resolution >15,000, collision energies 20-40 eV stepped.

- Include quality control samples: pooled quality controls, solvent blanks, and reference standard mixtures.

Data Preprocessing and Feature Detection

- Convert raw data to open formats (mzXML, mzML, or .MGF) using tools like MSConvert [6].

- Process data with feature detection tools (e.g., MZmine, OpenMS, XCMS) to extract chromatographic features [7].

- Align features across samples and perform gap filling to address missing values.

- Export feature tables containing m/z, retention time, and intensity values alongside MS/MS spectra in .MGF format.

Molecular Networking and Annotation

- Upload data to GNPS platform or implement standalone workflow using the GNPS environment.

- Create molecular network using FBMN workflow with these key parameters: minimum cosine score 0.7, minimum matched peaks 6, network topK 10 [8].

- Annotate nodes using spectral library matching against public (GNPS) and in-house libraries.

- Inspect network in Cytoscape for visualization and manual validation of annotations.

- Utilize advanced tools such as MolNetEnhancer to integrate chemical class predictions [6].

Knowledge-Driven Networking Protocol: Two-Layer Interactive Networking

Knowledge Base Curation

- Compile metabolic databases including KEGG, MetaCyc, and HMDB to establish core metabolite and reaction knowledge [2].

- Apply graph neural network (GNN) to predict additional reaction relationships beyond known transformations.

- Generate unknown metabolites using BioTransformer or similar tools to expand coverage [2].

- Construct comprehensive Metabolic Reaction Network (MRN) with enhanced connectivity and metabolite coverage.

Experimental Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Acquire LC-MS/MS data using standardized protocols as described in Section 3.1.

- Perform MS1 and MS2 feature extraction using tools compatible with the knowledge-driven platform (e.g., XCMS for MetDNA3).

- Align features across samples and perform quality control to ensure data integrity.

Two-Layer Network Construction and Annotation

- Pre-map experimental features onto the knowledge-based MRN through sequential MS1 matching.

- Apply reaction relationship mapping and MS2 similarity constraints to establish two-layer network topology [2].

- Execute recursive annotation propagation leveraging cross-network interactions between data and knowledge layers.

- Validate annotations using orthogonal approaches including reference standards when available.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Networking

| Category | Item/Resource | Specifications | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography | HILIC Column (e.g., BEH Amide) | 2.1×100 mm, 1.7 μm | Polar metabolite separation |

| Reversed-Phase Column (e.g., C18) | 2.1×100 mm, 1.7 μm | Non-polar metabolite separation | |

| MS Standards | Reference Standard Mixture | Quality control samples | Retention time alignment; System performance monitoring |

| Data Processing | MSConvert (ProteoWizard) | mzXML/mzML conversion | Raw data standardization for platform compatibility [6] |

| MZmine 3 | Feature detection & alignment | Chromatographic feature extraction [7] | |

| Computational Platforms | GNPS | Web-based platform | Data-driven molecular networking & spectral library matching [8] |

| MetDNA3 | R/Python package | Knowledge-driven two-layer networking [2] | |

| Cytoscape 3.9+ | Network visualization | Interactive network exploration & annotation | |

| Spectral Libraries | GNPS Libraries | Community-curated spectra | Reference spectra for annotation [6] |

| In-House Library | Custom standards | Laboratory-specific metabolite identification |

Integrated Two-Layer Networking: Advanced Implementation

The most significant recent advancement in metabolite annotation is the development of integrated two-layer networking approaches that synergistically combine data-driven and knowledge-driven strategies. This methodology, as implemented in MetDNA3, establishes "a two-layer interactive networking topology that integrates data-driven and knowledge-driven networks to enhance metabolite annotation" [2].

Implementation Protocol:

- Curate comprehensive MRN using GNN-based prediction as described in Section 3.2.

- Pre-map experimental features onto the knowledge-based MRN through sequential MS1 matching, reaction relationship mapping, and MS2 similarity constraints.

- Establish two-layer network topology with the MRN representing the knowledge layer and experimental features forming the data layer.

- Execute interactive annotation propagation leveraging cross-network interactions, achieving "over 10-fold improved computational efficiency" compared to previous approaches [2].

- Annotate seed metabolites with chemical standards (>1600 metabolites) and propagate annotations to >12,000 putative metabolites through network-based propagation.

Performance Advantages:

- Enhanced coverage: Overcomes limitations of sparse knowledge databases while maintaining biological relevance

- Improved accuracy: Integrates experimental constraints with biochemical plausibility

- Novel metabolite discovery: Enabled identification of "two previously uncharacterized endogenous metabolites absent from human metabolome databases" [2]

- Computational efficiency: 10-fold improvement in processing speed facilitates analysis of large sample cohorts

This integrated approach represents the current state-of-the-art in metabolite annotation, effectively addressing the fundamental limitations of both standalone data-driven and knowledge-driven methods while leveraging their respective strengths for comprehensive metabolite characterization.

Molecular networking has revolutionized the analysis of untargeted mass spectrometry data by providing a visual and computational framework to organize complex metabolomic data and annotate metabolites. This approach has evolved from initial methods that grouped molecules based on tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) similarity to sophisticated systems that integrate quantitative data, ion-mobility separation, and biological knowledge. The Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform has been a cornerstone of this evolution, growing into a comprehensive mass spectrometry ecosystem that supports community-wide data sharing and analysis [9].

A significant recent advancement is the development of two-layer interactive networking topologies that integrate data-driven and knowledge-driven networks. This approach, implemented in tools such as MetDNA3, substantially enhances the coverage, accuracy, and efficiency of metabolite annotation, enabling the discovery of previously uncharacterized metabolites [2]. This Application Note traces this technological progression, provides detailed protocols for key methodologies, and summarizes essential reagents for implementation.

The GNPS Foundation and the Rise of Feature-Based Molecular Networking

The GNPS Ecosystem

Launched in 2012, GNPS established itself as an open-access knowledge base for the organization and sharing of raw, processed, or annotated fragmentation mass spectrometry data [9]. Its core analysis workflow, Classical Molecular Networking, uses the MS-Cluster algorithm to group related MS/MS spectra based on spectral similarity, visualized as molecular families in a network graph [10]. This approach allows researchers to explore chemical space and identify structurally related molecules, even in the absence of reference standards.

Advancements with Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN)

A major evolutionary step occurred with the introduction of Feature-Based Molecular Networking. Unlike classical MN, which relies solely on MS2 spectral data, FBMN incorporates MS1-level information—such as chromatographic retention time, ion mobility, and isotopic patterns—after data is processed by feature detection tools like MZmine, OpenMS, or MS-DIAL [10].

Table 1: Key Advantages of Feature-Based Molecular Networking over Classical Molecular Networking

| Aspect | Classical Molecular Networking | Feature-Based Molecular Networking |

|---|---|---|

| Isomer Resolution | Limited, can collapse isomers | High, distinguishes isomers via LC retention time & ion mobility |

| Quantitative Analysis | Uses spectral counts or precursor ion counts (less accurate) | Uses LC-MS feature abundance (peak area/height); enables robust statistical analysis |

| Data Redundancy | Can create multiple nodes for the same compound | Provides a single consensus MS2 spectrum per LC-MS feature |

| Quantitative Performance | Lower R² values in dilution series | Higher R² values (mostly >0.7 in a serial dilution study) |

| Ion Mobility Integration | Not supported | Supported, adding another dimension for separation |

FBMN provides a more accurate and organized representation of the chemical data, simplifying the discovery process and improving the reliability of downstream statistical analyses [10]. It remains the recommended method for analyzing individual LC-MS/MS metabolomics studies.

Protocol: Conducting a Feature-Based Molecular Networking Analysis on GNPS

This protocol outlines the steps to perform an FBMN analysis using data processed with MZmine, one of the supported software tools.

Materials and Software

- LC-MS/MS Data: Raw data files in a standard format (e.g., .mzML, .mzXML).

- MZmine Software: Installed on a local computer (https://mzmine.github.io/).

- GNPS Account: A free user account on the GNPS website (https://gnps.ucsd.edu).

Procedure

Data Preprocessing in MZmine:

- Import your raw LC-MS/MS data files into MZmine.

- Perform mass detection to identify masses in each scan.

- Run the ADAP chromatogram builder module to construct chromatograms from the mass lists.

- Execute the Chromatogram deconvolution module to resolve co-eluting compounds and define chromatographic features.

- Use the Isotopic peak grouper to group features belonging to the same metabolite.

- Align features across all samples using the Join aligner module.

- Filter and gap-fill the feature list to handle missing values.

- Export the results for GNPS FBMN:

- MS2 Spectral Summary (.MGF file): Contains one representative MS2 spectrum per feature.

- Feature Quantification Table (.CSV file): Contains information on each feature's m/z, retention time, and intensity across all samples.

Job Submission on GNPS:

- Navigate to the "Feature-Based Molecular Networking" workflow on the GNPS website.

- Upload the exported .MGF and .CSV files.

- Set key parameters:

- Precursor Ion Mass Tolerance: Typically 0.02 Da for high-resolution instruments.

- Fragment Ion Mass Tolerance: Typically 0.02 Da.

- Minimum Cosine Score for Network Edges: A value of 0.7 is a common starting point.

- Minimum Matched Fragment Peaks: Set to 4-6 to ensure meaningful spectral comparisons.

- Submit the job. Processing time depends on dataset size and GNPS server load.

Results Interpretation:

- Once completed, explore the molecular network using the Cytoscape.js visualizer within GNPS.

- Nodes in the network represent LC-MS features; edges connect features with similar MS2 spectra.

- Use the embedded spectral library search to annotate nodes by matching experimental spectra to reference libraries.

- Leverage the quantitative data (feature abundances) to perform differential analysis between sample groups directly within the network view.

Advanced Topologies: Two-Layer Interactive Networking

The MetDNA3 Approach

While FBMN improved data-driven networking, a paradigm shift occurred with the integration of knowledge-driven networks. The two-layer interactive networking topology, implemented in MetDNA3, addresses the challenge of annotating metabolites lacking chemical standards by combining experimental data with curated biochemical knowledge [2].

This method establishes a knowledge layer, comprising a comprehensive Metabolic Reaction Network (MRN) of metabolites and their predicted reaction relationships, and a data layer, consisting of experimental MS features. These layers are interactively pre-mapped through sequential MS1 m/z matching, reaction relationship mapping, and MS2 similarity constraints [2]. This creates a coherent topology that enables highly efficient, recursive annotation propagation from a small number of confidently identified "seed" metabolites to thousands of unknown features.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of the Two-Layer Networking in MetDNA3

| Metric | Performance | Context / Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Curated MRN Size | 765,755 metabolites; 2,437,884 reaction pairs | Vastly expanded coverage over known databases (KEGG, HMDB, MetaCyc) [2] |

| Computational Efficiency | >10-fold improvement | Enables practical application to large-scale datasets [2] |

| Annotation Power | >1,600 seed metabolites; >12,000 putatively annotated metabolites via propagation | Demonstrated on common biological samples [2] |

| Novel Discovery | Two previously uncharacterized endogenous metabolites | Identified metabolites absent from human metabolome databases [2] |

Protocol: Implementing a Two-Layer Networking Analysis with MetDNA3

This protocol describes the workflow for using MetDNA3 for recursive metabolite annotation.

Materials and Software

- LC-MS/MS Data: Peak table with m/z, retention time, and MS2 spectrum for each feature.

- MetDNA3 Software: Accessible via the web server at http://metdna.zhulab.cn/.

- Sample Metadata: Information about sample groups (e.g., control vs. treatment).

Procedure

Data Preparation:

- Process your raw LC-MS/MS data using a tool like MZmine or XCMS to generate a peak table.

- The peak table must contain:

- Feature ID

- m/z value

- Retention time (in seconds)

- Peak intensity across all samples

- A corresponding MS2 spectrum for each feature (in .MSP or .MGF format).

- Format the peak table according to the MetDNA3 template guidelines.

Job Submission and Parameter Setting:

- Upload the formatted peak table and MS2 spectral file to the MetDNA3 server.

- Select the appropriate adduct ion types expected in your data (e.g., [M+H]+, [M+Na]+ for positive mode).

- Set the MS1 and MS2 mass tolerance (e.g., 10 ppm and 0.02 Da, respectively).

- Specify the retention time tolerance for matching features to seed annotations.

- Define the sample groups for differential analysis if desired.

- Initiate the analysis.

Analysis and Interpretation:

- MetDNA3 will first perform a library search to identify seed metabolites with high confidence.

- The algorithm then performs recursive annotation propagation through the two-layer network.

- Explore the results through the interactive visualization interface, which displays both the knowledge and data layers.

- The output will provide annotation results at various confidence levels, from high-confidence seeds to putative annotations propagated through the network.

- Results can be exported for further biological interpretation and validation.

MetDNA3 Two-Layer Networking Workflow

Successful implementation of advanced molecular networking relies on a combination of computational tools, databases, and chemical reagents.

Table 3: Key Resources for Advanced Molecular Networking

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| GNPS [9] | Web Platform | Core ecosystem for molecular networking, library search (MS/MS), and repository-scale meta-analysis. |

| MetDNA3 [2] | Software/Web Tool | Performs two-layer interactive networking for recursive metabolite annotation. |

| MZmine [10] | Software | Detects and quantifies LC-MS features; data pre-processing for FBMN. |

| C-SPIRIT Annotation Framework [11] | Database/Framework | Provides an ontological framework for annotating plant and microbial metabolites in biological context. |

| Post-column Derivatization Reagents (e.g., L-cysteine, AQC, Hydroxylamine) [12] | Chemical Reagents | Generate orthogonal structural information (e.g., functional group data) to improve MS/MS annotation. |

| SIRIUS/CSI:FingerID | Software | Provides in silico fragmentation and compound structure prediction for metabolite identification. |

The field of molecular networking has matured significantly from its origins in spectral similarity clustering on GNPS. The development of Feature-Based Molecular Networking integrated crucial quantitative and isomeric resolution, while the latest two-layer interactive topologies, such as MetDNA3, seamlessly blend data-driven discovery with knowledge-driven inference. These advancements are systematically overcoming the critical bottleneck of metabolite annotation in untargeted metabolomics. By providing detailed protocols and a curated toolkit, this Application Note equips researchers to leverage these powerful methods, accelerating the transformation of complex mass spectrometry data into meaningful biological discovery and therapeutic insights.

MS2 Spectral Similarity, Cosine Scoring, and Network Visualization

Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics relies on the analysis of tandem mass spectrometry (MS2) data to identify and annotate metabolites in complex biological mixtures. A core principle underlying this process is that the fragmentation pattern captured in an MS2 spectrum serves as a unique fingerprint for a molecule. Computational methods that can compare these spectra effectively are therefore fundamental to metabolite annotation. This application note details the key concepts, methodologies, and protocols for using MS2 spectral similarity, with a focus on cosine scoring and its application in molecular network visualization. These techniques are essential components of modern metabolomics workflows, enabling researchers to navigate the vast chemical space present in biological samples and to move from unknown spectra to putative annotations.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Data

Core Similarity Metrics

Spectral similarity measures serve as a proxy for structural similarity between molecules. The table below summarizes the primary metrics used in the field.

Table 1: Core MS2 Spectral Similarity Metrics and Their Characteristics

| Metric Name | Type | Key Principle | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cosine Similarity [13] [14] | Classical | Measures the angular similarity between two spectra represented as vectors of peak intensities. | Spectral library matching; foundational score for molecular networking. |

| Modified Cosine [15] | Classical | Extends cosine similarity by accounting for neutral losses and the difference in precursor mass. | Improved analogue search and identification of structurally related compounds. |

| Spec2Vec [16] | Unsupervised ML | Adapts Word2Vec from NLP; learns fragmental relationships from co-occurrences to create spectral embeddings. | Library matching and molecular networking with better correlation to structural similarity. |

| MS2DeepScore [17] | Supervised ML | Uses a Siamese neural network trained to predict structural similarity (Tanimoto score) from spectrum pairs. | High-accuracy analogue search and retrieval of structurally similar molecules. |

Performance Benchmarking of Similarity Measures

The selection of a similarity metric significantly impacts annotation outcomes. Benchmarking studies evaluate these metrics based on their ability to correlate spectral similarity with true chemical structural similarity.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Spectral Similarity Metrics

| Metric | Correlation with Structural Similarity | Key Performance Findings | Computational Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cosine/Modified Cosine | Moderate | Standard approach but can yield high false positive rates; performance is highly dependent on peak matching parameters (tolerance, min_match) [16]. | Loop-based implementations (e.g., MatchMS) can be slow for large-scale comparisons [13]. |

| Spec2Vec | Improved | Correlates better with structural similarity than cosine-based scores; subsequently gives better performance in library matching tasks [16]. | Unsupervised training on spectral collections; similarity computation is fast and scalable [16]. |

| MS2DeepScore | High | Predicts Tanimoto scores with an RMSE of ~0.15; outperforms classical metrics in retrieving chemically related compounds [17]. | Requires a trained model; integration into tools like MS2Query enables efficient large-scale searches [15]. |

| BLINK (Cosine) | Moderate (Equivalent) | Provides identical cosine scores to conventional methods with >99% agreement when using appropriate bin widths [13]. | Extremely fast (3000x faster than MatchMS) due to vectorized sparse matrix operations, enabling database searches in minutes instead of days [13]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Spectral Library Matching Using Cosine Similarity

This protocol describes how to perform classical and high-speed cosine similarity scoring for identifying metabolites by matching experimental spectra against a reference library.

Materials and Reagents

- Reference Spectral Library: A curated library in a compatible format (e.g.,

.msp,.mgf). Example: Public GNPS libraries [14]. - Experimental MS2 Data: LC-MS/MS data files converted to an open format (

.mzML,.mzXML).

Procedure

Data Preprocessing:

Parameter Configuration:

- Set the fragment ion mass tolerance. This is instrument-dependent; typically 0.01-0.02 Da for high-resolution instruments (Q-TOF, Orbitrap) and 0.5 Da for low-resolution instruments (ion traps) [14].

- Define the minimum number of matched peaks, often set to 6 [14].

- Set a cosine score threshold for positive matches; a value of 0.7 is commonly used [14].

Similarity Scoring (Choose one method):

- Standard Method (e.g., with MatchMS): Use a loop-based implementation to align fragment ions within the specified mass tolerance and calculate the cosine score for each experimental spectrum against each library spectrum [13].

- High-Speed Method (e.g., with BLINK):

- Discretize spectra by converting m/z values to integer bins based on a user-defined bin width (default 0.001 Da) [13].

- Use sparse matrix operations and a "blurring" kernel to link m/z bins within the tolerance window, bypassing pairwise alignment [13].

- Multiply the intensity matrices to simultaneously compute cosine scores for all spectrum pairs [13].

Result Interpretation:

- Rank library matches for each experimental spectrum by their cosine score.

- Consider matches above the defined score and matched peak thresholds as putative identifications.

Protocol 2: Creating a Molecular Network in GNPS

This protocol outlines the steps to create a molecular network using the GNPS platform, which uses modified cosine similarity to cluster related spectra [14].

Materials and Reagents

- MS2 Data Files: Collision-Induced Dissociation (CID) or Higher-energy C-trap Dissociation (HCD) MS2 data in

.mzML,.mzXML, or.mgfformat. - (Optional) Metadata File: A text file organizing input files into experimental groups (e.g., control vs. case).

Procedure

Data Preparation and Upload:

- Convert your MS2 data to the required file formats.

- Navigate to the GNPS website (https://gnps.ucsd.edu) and select "Create Molecular Network" [14].

- Upload your data files and optional metadata file.

Parameter Setting (Critical Steps):

- Basic Options:

- Advanced Network Options:

- Min Pairs Cos: Set the minimum cosine score for an edge. The default is 0.7 [14].

- Minimum Matched Fragment Ion: Set the minimum number of common fragments. The default is 6 [14].

- Node TopK: Restrict the maximum number of neighbors per node to 10 to simplify the network [14].

- Run MSCluster: Set to "Yes" to cluster near-identical spectra before networking [14].

- Maximum Connected Component Size: Set to 100 (or 0 for unlimited) to break overly large networks [14].

Workflow Submission and Monitoring:

- Submit the job. Processing time varies from minutes for small datasets to hours for large datasets [14].

- Monitor the job status on the provided status page.

Network Visualization and Analysis:

- Once complete, use the GNPS web interface to explore the results.

- Visualize the network in the browser, where nodes represent consensus spectra and edges represent spectral similarity.

- Examine "View All Library Hits" to see annotated nodes and propagate annotations within clusters of related, unannotated nodes.

Protocol 3: Advanced Analogue Search with MS2Query

This protocol uses machine learning to find both exact matches and structurally similar analogues for experimental spectra, increasing annotation rates [15].

Materials and Reagents

- MS2Query Installation: Install the Python library via

pip install ms2query. - Pretrained Models and Libraries: Download the required files as per MS2Query documentation.

Procedure

Data Preparation:

- Load and preprocess your MS2 spectra (e.g., using

matchms). Filter out low-quality spectra and normalize metadata.

- Load and preprocess your MS2 spectra (e.g., using

Model and Library Setup:

- Load the pretrained MS2Query model and the reference spectral library.

Analogue Search:

- Run MS2Query on your dataset without preselecting based on precursor m/z.

- The tool will: a. Use MS2DeepScore to compare all query and library spectra [15]. b. Select the top 2000 candidate spectra [15]. c. Re-rank candidates using a random forest model that incorporates Spec2Vec similarity, precursor m/z, and a novel feature—the weighted average MS2Deepscore of chemically similar library molecules [15].

Result Interpretation:

- MS2Query returns a ranked list of potential analogues and exact matches for each query spectrum.

- The random forest score (between 0-1) indicates confidence; apply a threshold to filter unreliable matches.

- On a benchmark set, this method achieved an average Tanimoto score of 0.63 for predicted analogues, a significant improvement over cosine-based methods [15].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points for the application of different spectral similarity and networking protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit

A selection of key software tools and resources essential for implementing the protocols described in this note.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Resources for MS2 Spectral Analysis

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Access/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNPS | Web Platform | Ecosystem for MS2 data analysis, including molecular networking, library search, and FBMN [14] [7]. | https://gnps.ucsd.edu |

| MatchMS | Python Package | Standardized tool for MS2 data processing, filtering, and calculating cosine similarity scores [13]. | https://github.com/matchms/matchms |

| BLINK | Python Package | Ultrafast cosine similarity scoring algorithm, enabling large-scale database searches in minutes [13]. | Integrated into MatchMS |

| MS2Query | Python Package | Machine learning tool for reliable and scalable analogue and exact match searching [15]. | https://github.com/iomega/MS2Query |

| Spec2Vec & MS2DeepScore | Python Packages | Advanced ML-based spectral similarity measures for improved retrieval of structurally similar compounds [16] [17]. | Available via matchms and separate installations |

| MZmine | Standalone Software | Flexible, modular platform for LC-MS data preprocessing, often used for feature detection prior to FBMN [18]. | https://mzmine.github.io/ |

Untargeted mass spectrometry (MS) has emerged as a pivotal technique for comprehensively profiling the small molecule composition of complex biological and environmental samples. Despite its power, the field grapples with a fundamental challenge: the vast majority of detected signals—often exceeding 90%—remain chemically uncharacterized, constituting what researchers term "chemical dark matter" [19]. This limitation severely constrains our ability to fully interpret metabolomic data and discover novel biologically significant compounds.

Molecular networking strategies have revolutionized metabolite annotation by enabling the organization of MS data based on spectral similarity and facilitating the propagation of annotations within molecular families [6]. However, traditional approaches still primarily rely on library matches, leaving a significant portion of the chemical space unexplored. This application note details advanced computational frameworks and experimental protocols designed to systematically bridge this knowledge gap, moving the field from characterizing knowns to deciphering unknowns.

Table 1: The Scale of the Metabolite Annotation Challenge in Untargeted MS

| Aspect of Challenge | Typical Value or Statistic | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| General Annotation Rate | Often < 10% of LC-MS peaks [19] | Vast majority of acquired data lacks chemical interpretation |

| Specific GNPS Annotation | Up to ~13% of LC-MS peaks [19] | Even with advanced networking, significant unknowns remain |

| Spectral Library Matching | Sometimes < 5% of detected peaks [19] | Limited by incompleteness of reference libraries |

| Earth Microbiome Project | 56,674 peaks (m/z 100-900) from 572 samples [19] | Illustrates the data volume and complexity from diverse biomes |

| DI-MS Data Complexity | Routinely >100,000 m/z values per sample [20] | High-throughput methods generate immense data requiring prioritization |

Advanced Strategies for Illuminating the Chemical "Dark Matter"

Chemical Characteristics Vectors (CCVs): Utilizing Unannotated Features

The CCV approach represents a paradigm shift by chemically characterizing samples without requiring complete structural identifications. This method leverages "chemical dark matter" that would otherwise be discarded [19].

Experimental Protocol 1: Constructing Chemical Characteristics Vectors

- Data Preprocessing: Use SIRIUS software (version 4.14 or newer) for feature extraction and alignment. Set allowed elements for formula prediction to CHNOPS plus Cl, Br, B, and Se based on isotope patterns. Define mass deviation tolerance at 10 ppm or 0.002 Da [19].

- Molecular Fingerprint & Compound Class Prediction: For LC-MS peaks with MS/MS data, calculate probabilistic molecular fingerprints (MFP) using CSI:FingerID and predict compound classes (CC) using CANOPUS within SIRIUS [19].

- Binarization: Transform all probabilistic MFPs and CCs to binary values (presence/absence of specific chemical characteristics) using a probability threshold of 0.5 [19].

- Vector Creation: Average the binarized chemical characteristics across all profiled MS/MS spectra within a sample to create a standardized CCV. This vector describes the ratio of compounds with specific chemical properties in the sample, enabling quantitative comparisons between samples and biomes [19].

Figure 1: Workflow for constructing Chemical Characteristics Vectors (CCVs) from untargeted MS data.

Knowledge-Guided Multi-Layer Network (KGMN): From Knowns to Unknowns

The KGMN framework enables the systematic annotation of unknown metabolites by propagating structural information from known seed metabolites through an integrated network [21].

Experimental Protocol 2: Implementing the KGMN Framework

- Seed Annotation: Annotate initial seed metabolites by matching MS1 m/z, retention time, and MS/MS spectra against standard metabolite libraries [21].

- Network Layer 1 - Knowledge-Based Metabolic Reaction Network (KMRN):

- Map seed metabolites into a reaction network (e.g., from KEGG) to retrieve reaction-paired neighbors.

- Expand the network by performing in silico enzymatic reactions using known metabolites as substrates, generating possible unknown products linked to their precursors. This expands the network from known to unknown chemical space [21].

- Network Layer 2 - Knowledge-Guided MS² Similarity Network:

- For reaction-paired neighbors from Layer 1, match calculated MS1 m/z and predicted retention times to experimental data.

- Use surrogate MS/MS spectra from seed metabolites for spectral matching.

- Annotate matched peaks as putative neighbors and link them to seeds, using four constraints: MS1 m/z, RT, MS/MS similarity, and metabolic biotransformation type (e.g., +2H for reduction, -CO₂ for decarboxylation) [21].

- Repeat this process recursively, using newly annotated metabolites as seeds until no new metabolites can be annotated.

- Network Layer 3 - Global Peak Correlation Network:

- Use all annotated peaks as base peaks.

- Extract different ion forms (adducts, isotopes, neutral losses, in-source fragments) from the peak list by searching for common transformations within co-eluted peaks.

- Construct a peak correlation subnetwork for each metabolite, connecting the base peak to its different ion forms to comprehensively describe its ionization profile [21].

Figure 2: The three-layer structure of the Knowledge-Guided Multi-Layer Network (KGMN) for annotating unknowns from known seeds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Advanced Metabolite Annotation

| Tool/Solution | Primary Function | Role in Bridging Unknown Chemical Space |

|---|---|---|

| SIRIUS + CSI:FingerID [19] | Predicts molecular fingerprints from MS/MS data | Enables characterization without definitive identification, utilizing unannotated peaks. |

| CANOPUS [19] | Predicts compound classes from MS/MS data | Provides broad chemical categorization when precise structures are unknown. |

| GNPS Molecular Networking [6] | Constructs MS/MS similarity networks | Groups related molecules into molecular families, allowing annotation propagation. |

| MetaboShiny [20] | R/Shiny package for DI-MS data analysis | Supports annotation across >30 databases, integrates statistics and machine learning for m/z prioritization. |

| KGMN [21] | Integrates multiple data and knowledge networks | Systematically propagates annotations from knowns to unknowns using biochemical reasoning. |

| ION | Not specified in search results | (Note: Tool mentioned in user request but not found in provided search results) |

Concluding Protocol: An Integrated Workflow for Unknown Exploration

A robust strategy for tackling unknown chemical space combines multiple complementary approaches.

Integrated Experimental Protocol

- Data Acquisition: Perform LC-HRMS/MS in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. Ensure high mass accuracy (<10 ppm) for precursor ions [19] [22].

- Initial Processing and Classical Molecular Networking:

- In-Depth Computational Analysis:

- Process data with SIRIUS for formula prediction and run CSI:FingerID and CANOPUS to generate molecular fingerprints and compound class predictions for all possible features [19].

- Construct CCVs to compare overall chemical composition across sample groups and identify differentiating chemical traits [19].

- Implement KGMN, using annotations from Step 2 as seeds, to recursively annotate unknown metabolites through the multi-layer network [21].

- Validation and Prioritization:

- Corroborate putative unknown annotations using in silico MS/MS tools (e.g., MetFrag, CFM-ID) [21].

- Use statistical analysis and machine learning (e.g., via MetaboShiny) to prioritize recurrent unknown metabolites across datasets for further investigation using repository mining or chemical synthesis [21] [20].

Implementing Molecular Networking: Practical Workflows and Platform Selection

Molecular networking has emerged as a powerful computational strategy for visualizing and annotating metabolites in complex biological samples, revolutionizing untargeted metabolomics. This technique groups metabolites based on the similarity of their mass spectrometry fragmentation patterns, allowing researchers to efficiently discover and identify novel natural products and endogenous metabolites. The workflow encompasses multiple critical stages, from initial sample collection to final biological interpretation, with each step introducing potential variability that can significantly impact data quality and reliability. This application note provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for implementing a robust molecular networking workflow, framed within the context of metabolite annotation research for drug discovery and development. The protocols integrate both established methods and cutting-edge advancements, including feature-based molecular networking (FBMN) and the innovative two-layer interactive networking approach, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for metabolomics studies [18] [2] [6].

Sample Preparation and Metabolite Extraction

Proper sample preparation is fundamental to obtaining high-quality metabolomics data, as metabolites can have rapid turnover times—some intermediates in primary metabolism turn over within fractions of a second [5].

Sample Collection and Quenching

- Tissue Sampling: For most applications, quick excision and snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen is recommended. Subsequent storage should be at constant −80°C. For bulky tissues (thicker than a standard leaf), submersion in liquid nitrogen is insufficient as the center cools slowly. In these cases, use freeze-clamping, where tissue is vigorously squashed flat between two prefrozen metal blocks [5].

- Sample Storage: Deep-frozen samples should be processed as quickly as experimentally feasible. Storage for weeks or months should be avoided or performed in liquid nitrogen. The best approach for many metabolic analyses is removing aqueous or organic solvent to create a dry residue. Short-term storage of liquid aqueous or organic solvent extracts, even at −20°C, is not recommended [5].

- Freeze-Thaw Considerations: Standardization protocols require single-use portioning and limiting freeze-thaw cycles to ≤2-3 cycles for reliable biomarker discovery [18].

Metabolite Extraction Optimization

Response surface methodology has been employed to optimize ultrasound-assisted extraction conditions. The optimized parameters for plasma samples are detailed in Table 1 [18].

Table 1: Optimized Extraction Parameters for Plasma Samples

| Parameter | Optimized Condition | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Concentration | 300% methanol | Maximizes metabolite recovery |

| Freezing Temperature | −20°C | Preserves metabolite stability |

| Freezing Duration | 40 minutes | Ensures complete sample freezing |

| Sonication Time | 5 minutes | Enhances extraction efficiency |

Quality Control Measures

- Replication Strategy: Biological replication is significantly more important than technological replication and should involve at least three and preferably more replicates. Technical replication involves independent performance of the complete analytical process rather than repeat injections of the same sample [5].

- Randomization: Implement careful spatiotemporal randomization of biological replicates throughout experiments, sample preparation workflows, and instrumental analyses using randomized-block design to minimize the influence of uncontrolled variables [5].

- Standardized Reference Materials: Use aliquots of a chemically defined repeatable standard mixture or standardized biological reference sample stored alongside samples, particularly for studies extending over long periods [5].

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Parameters

Optimal FBMN construction parameters include a 25-minute gradient elution time, 50 mm chromatographic column length, and high sample concentration. These parameters enhance network connectivity and annotation performance [18].

For LC-MS/MS-based metabolomics experiments, data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode is typically employed. In DDA mode, the MS1 spectra of the substance is first collected, and only when the MS1 spectra meets certain conditions is the collection of the MS2 spectra triggered. This mode provides highly selective and accurate MS2 spectra [6].

Data Conversion and Formatting

The GNPS web platform only supports mzXML, mzML, and .MGF formats. MSConvert can be used to convert collected data to these formats. The converted data can then be uploaded to the GNPS web platform with an FTP client such as WinSCP [6].

Addressing Analytical Challenges

Electrospray ionization typically produces multiple ion species beyond just protonated (ESI+) or deprotonated (ESI-) molecular ions. Researchers frequently observe other ion adducts such as Na+, K+, NH4+, and acetonitrile in positive mode, or Cl- in negative mode, along with in-source fragments such as H2O and other neutral losses. Tools like ion identity molecular networking (IIMN) can group different ion species and in-source fragments within molecular networks, reducing data redundancy [23].

Table 2: Key Data Acquisition Parameters for Molecular Networking

| Parameter | Recommendation | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition Mode | Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) | Balances MS1 and MS2 data collection |

| Gradient Elution | 25 minutes | Optimal separation for FBMN |

| Column Length | 50 mm | Compatible with FBMN requirements |

| Dynamic Exclusion | Enabled | Reduces scanning of duplicate ions |

| Data Formats | mzXML, mzML, .MGF | GNPS compatibility |

Computational Processing and Molecular Networking

Molecular Networking Fundamentals

Classical molecular networking groups molecules based on the similarity of their MS2 spectra. When molecules with similar structures collide with the same intensity, they may produce the same ion fragments. The GNPS platform compares all MS2 spectra in a dataset and calculates alignment scores to construct a molecular network where nodes represent MS2 spectra and edges connect spectra with similarity scores above a threshold [6].

Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN)

FBMN integrates LC-MS1 feature detection to account for chromatographic information, improving isomer differentiation. A comparative evaluation of GNPS and MZmine implementations of FBMN reveals that GNPS is recommended for studies prioritizing comprehensive annotation coverage and discovery-oriented metabolomics, while MZmine is preferred for method development or applications requiring local processing without external data upload [18].

Advanced Networking Approaches

Two-Layer Interactive Networking

A knowledge- and data-driven two-layer networking approach significantly enhances metabolite annotation. This method integrates data-driven networks (where nodes represent experimental MS features and edges denote relationships) with knowledge-driven networks (where nodes represent metabolites and edges define relationships such as metabolic reactions). The workflow, implemented in MetDNA3, involves:

- Curation of Metabolic Reaction Network: Integrating multiple metabolite knowledge databases (KEGG, MetaCyc, and HMDB) with network reconstruction and expansion using graph neural network-based prediction of reaction relationships.

- Pre-mapping Experimental Data: Experimental features are pre-mapped onto the knowledge-based metabolic reaction network through sequential MS1 m/z matching, reaction relationship mapping, and MS2 similarity constraints.

- Annotation Propagation: Enables interactive annotation propagation with over 10-fold improved computational efficiency [2].

Multiplexed Chemical Metabolomics (MCheM)

MCheM enhances metabolite annotation by integrating orthogonal post-column derivatization reactions. This method leverages functional group-specific derivatization to generate orthogonal chemical data, addressing challenges in non-targeted LC-MS/MS analysis where only a small fraction (2-10%) of acquired spectra typically match existing libraries [23].

The hardware setup for MCheM is practical for existing LC-MS/MS platforms, requiring primarily an additional PEEK capillary, a t-splitter, and reagents. The software is freely available for academic researchers [23].

Metabolite Annotation and Structural Elucidation

Spectral Library Matching

Standard library-based spectral matching remains the gold standard for metabolite annotation but is limited to known metabolites with available reference spectra. The GNPS library currently contains approximately 573,579 spectra corresponding to 64,133 unique structures [23].

In Silico Annotation Tools

In silico spectral matching tools that compute MS/MS spectra or fragmentation trees from structural libraries have much larger structural coverage of chemical space. These include:

- SIRIUS: Integrates MS/MS spectra with fragmentation trees for structural annotation.

- DEREPLICATOR+: Enables high-throughput annotation of peptidic natural products.

- MolNetEnhancer: Provides comprehensive chemical classification and annotation within molecular networks [6].

Confidence Levels in Annotation

Metabolite identification confidence should be reported according to established guidelines:

- Level 1: Confidently identified compounds with confirmed structure using reference standards.

- Level 2: Putatively annotated compounds based on spectral similarity to libraries.

- Level 3: Putatively characterized compound classes based on characteristic chemical features.

- Level 4: Unknown compounds that can be differentiated but not annotated [5].

Functional Analysis and Biological Interpretation

Pathway Analysis Approaches

Functional analysis methods for metabolomics data can be categorized into three main types:

- Over-Representation Analysis (ORA): Identifies functional modules that have differentially expressed entities exhibiting greater variations between conditions than expected by chance.

- Functional Class Scoring (FCS): Addresses limitations of ORA by considering that small, yet coordinated changes in expression of functionally related entities can significantly impact pathways.

- Topology-based Pathway Analysis (TPA): Leverages pathway topology and interactions among omics features to more accurately represent underlying biological phenomena [24].

Integration with Multi-Omics Data

Advanced tools such as PaintOmics, OmicsNet, and IMPaLA support the integration of metabolomics data with other omics types (genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics) to investigate disease-relevant changes at multiple omics layers [24].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Networking Workflows

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol (300%) | Metabolite extraction solvent | Optimized plasma metabolite extraction [18] |

| AQC Reagent | Derivatization of amines | MCheM workflow for detecting primary/secondary amines [23] |

| Cysteine Reagent | β-lactone detection | MCheM workflow for identifying compounds with Michael systems or β-lactones [23] |

| Hydroxylamine | Aldehyde detection | MCheM workflow for identifying carbonyl-containing metabolites [23] |

| Global Standard Reference Extract | Quality control and instrument performance | Enables cross-laboratory data comparison and quality assessment [5] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Molecular Networking Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential stages from sample preparation to biological interpretation, with key substeps for each stage.

Diagram 2: Two-Layer Interactive Networking Topology. This diagram shows the integration of knowledge-driven and data-driven networks for enhanced metabolite annotation, demonstrating the pre-mapping process and annotation propagation between layers.

This workflow breakdown provides a comprehensive framework for implementing molecular networking in metabolite annotation research. By following these detailed protocols for sample preparation, data acquisition, computational processing, and biological interpretation, researchers can significantly enhance the coverage, accuracy, and efficiency of metabolite annotation in untargeted metabolomics. The integration of advanced approaches such as two-layer interactive networking and multiplexed chemical metabolomics represents the cutting edge of the field, enabling the discovery of previously uncharacterized metabolites and providing deeper insights into biological systems for drug development and biomarker discovery.

Metabolite annotation remains the central bottleneck in liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) based untargeted metabolomics [21]. The vast structural diversity of metabolites, coupled with the limitations of standard spectral libraries, has driven the development of sophisticated computational platforms to decipher complex metabolomic data [2]. Among these, GNPS, MZmine, and SIRIUS have emerged as cornerstone platforms, each offering distinct capabilities and analytical approaches [25] [26] [10]. These platforms form an essential toolkit for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to characterize known and discover novel metabolites in natural products, biological systems, and drug discovery pipelines.

Choosing the appropriate platform or combination thereof is critical for research success, as each system employs different fundamental strategies. GNPS (Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking) emphasizes community-driven spectral library matching and molecular networking [10]. MZmine provides a flexible framework for chromatographic feature detection and data preprocessing [27]. SIRIUS specializes in computational metabolite annotation using fragmentation tree analysis and machine learning [26]. This article provides a comparative analysis of these platforms, detailing their functionalities, integrated tools, and experimental protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal workflow for their metabolite annotation research.

Platform Comparisons: Core Functionalities and Integrated Ecosystems

Understanding the distinct focus and capabilities of each platform is fundamental to making an informed selection. The following table provides a systematic comparison of GNPS, MZmine, and SIRIUS across several critical dimensions.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of GNPS, MZmine, and SIRIUS Platforms

| Feature | GNPS | MZmine | SIRIUS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Community knowledge sharing, spectral library matching, and molecular networking [10] | LC-MS data preprocessing, feature detection, and alignment [27] | In-silico annotation, molecular formula, and structure prediction [26] |

| Core Functionality | Molecular networking via MS/MS spectral similarity; library search against public spectral libraries [7] [10] | Chromatographic peak picking, retention time alignment, ion identity networking, gap filling [10] [27] | Molecular formula prediction (SIRIUS); structure database ranking (CSI:FingerID); compound class prediction (CANOPUS) [25] [26] |

| Key Tools/Modules | Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN), Ion Identity Molecular Networking (IINM), MASST [10] | Various algorithms for peak detection, deconvolution, alignment, and filtering [18] [27] | SIRIUS, ZODIAC, CSI:FingerID, CANOPUS [25] [26] |

| Data Input | Processed MS/MS spectral data (.mgf) and feature quantification table from tools like MZmine, or raw spectra via "classical" networking [10] | Raw LC-MS/MS data files (.mzML, .mzXML) from vendor instruments [27] | Processed MS/MS spectral data (.mgf) from feature detection tools [26] [27] |

| Typical Output | Molecular networks visualizing spectral relationships; library annotations [10] [8] | Aligned feature list with quantification, MS/MS spectra for features (.mgf) [10] [27] | Putative molecular formulas, structural annotations, and compound class predictions [25] [26] |

| Strengths | Discovery-oriented; visualizes chemical space; propagates annotations; enables repository-scale analysis [21] [10] | High flexibility and control over preprocessing parameters; resolves isomers; handles quantitative data [18] [10] | High confidence in molecular formula; annotates unknowns without spectral libraries; provides compound class overview [25] [21] |

The synergy between these platforms is a key feature of modern metabolomics workflows. A typical pipeline involves using MZmine for data preprocessing and feature detection, followed by using the exported data for molecular networking and library matching on GNPS, and subsequently importing the results into SIRIUS for in-depth in-silico annotation of unannotated features [25] [26] [10]. This integrated approach leverages the unique strengths of each platform to achieve more comprehensive metabolite annotation than any single tool could provide.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

An Integrated Protocol for Comprehensive Metabolite Annotation

This protocol outlines a typical workflow that integrates MZmine, GNPS, and SIRIUS for the comprehensive annotation of metabolites from raw LC-MS/MS data [10] [27].

Step 1: Data Conversion and Feature Detection with MZmine

- Convert Raw Data: Use MSConvert (ProteoWizard) or similar tools to convert vendor-specific raw files into an open format like .mzML [27].

- Import into MZmine: Load the .mzML files into MZmine.

- Detect Chromatographic Peaks: Apply a mass detection algorithm followed by a chromatogram builder. The "Weighted Average" algorithm is commonly used. Key parameters include:

- Deconvolute Peaks: Use the "Local Minimum Search" deconvolution algorithm to resolve co-eluting ions.

- Align Retention Times: Apply the "Join Aligner" to align peaks across samples. Parameters include:

- m/z tolerance: 0.005 Da or 5–10 ppm.

- Retention time tolerance: 0.1–0.5 min.

- Gap Filling: Use the "Peak Finder" gap filler to reconstruct missing peaks in some samples.

- Isotopic Peak Grouper: Group adducts and isotopes.

- Export for GNPS/FBMN: Export the results as (a) a feature quantification table (.csv) and (b) a MS/MS spectral summary file (.mgf) using the "GNPS-FBMN" export module [10].

Step 2: Molecular Networking and Spectral Library Matching with GNPS

- Access GNPS: Navigate to the GNPS website (http://gnps.ucsd.edu) and select the "Feature-Based Molecular Networking" (FBMN) workflow [7] [10].

- Upload Files: Upload the .mgf (MS2 data) and .csv (feature quantification) files exported from MZmine.

- Set FBMN Parameters:

- Precursor Ion Mass Tolerance: 0.02 Da.

- Fragment Ion Mass Tolerance: 0.02 Da.

- Minimum Matched Peaks: 6.

- Minimum Cosine Score: 0.7.

- Network TopK: 10.

- Maximum Connected Component Size: 100.

- Library Search Minimum Matched Peaks: 6 [10].

- Submit Job and Analyze Results: After submission, inspect the molecular network. Nodes with golden circles indicate spectral library matches. The pie charts on nodes show the relative abundance of a feature across samples [10] [8].

Step 3: In-silico Annotation with SIRIUS

- Prepare Input: Use the same .mgf file exported from MZmine for SIRIUS input [26] [27].

- Import into SIRIUS: Drag and drop the .mgf file into the SIRIUS GUI, or use the command line.

- Configure Parameters:

- Instrument: Specify your instrument type (e.g., Orbitrap/Q-TOF).

- Ionization: Set positive/negative mode.

- Filters: Apply intensity and MS/MS level filters if needed.

- Run Annotation Modules:

- SIRIUS: Predicts molecular formulas from fragmentation trees.

- ZODIAC: Refines molecular formula rankings using Bayesian statistics [26] [2].

- CSI:FingerID: Performs structure database search using predicted molecular fingerprints [26].

- CANOPUS: Predicts compound classes directly from the MS/MS spectrum without requiring structural identification [25] [26].

- Export Results: Export the summary tables and .json files for further analysis.

Step 4: Data Integration and Visualization

- Map SIRIUS Results onto GNPS Networks: Use provided scripts (e.g., in a Jupyter notebook) to map the SIRIUS and CANOPUS annotations back onto the GNPS molecular network for visualization in Cytoscape [26]. This creates a powerful synthesis of community knowledge (GNPS) and computational prediction (SIRIUS).

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow and the flow of data between these platforms.

Diagram 1: Integrated Metabolomics Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential flow of data and analyses in a typical integrated metabolomics workflow, from raw data to final annotated results.

Protocol for Knowledge-Guided Metabolite Annotation Using Advanced Networking

For complex biological samples, knowledge-guided approaches can significantly enhance annotation coverage and accuracy, particularly for unknown metabolites [21] [2]. The following protocol leverages the KGMN (Knowledge-Guided Multi-layer Network) or MetDNA3 strategy, which integrates metabolic reaction networks with MS data.

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Seed Annotation

- Preprocess the LC-MS/MS data using MZmine (as in the previous protocol) to obtain a feature table and MS/MS spectra.

- Perform initial "seed" metabolite annotation by searching MS1 and MS2 data against standard spectral libraries in GNPS [21] [2].

Step 2: Constructing the Knowledge-Guided Multi-Layer Network

- Map Seeds to a Metabolic Reaction Network (MRN): The curated MRN contains known and predicted reaction relationships between metabolites [2].

- Retrieve Reaction-Paired Neighbors: For each seed annotation, retrieve its direct neighbors in the MRN. These neighbors represent potential metabolites that could be biosynthetically related (e.g., via reduction, hydroxylation, glycosylation) [21].

- Annotate Neighbors from Data: Search the LC-MS data for features matching the MS1 m/z, predicted retention time, and MS/MS similarity of these neighbor metabolites. The connection is constrained by the known biotransformation (e.g., +H2 for a reduction) [21].

- Recursive Propagation: Use the newly annotated metabolites as new "seeds" to propagate annotations further through the MRN, recursively expanding the annotation coverage [21] [2].

Step 3: Integration with Peak Correlation Network

- Construct a peak correlation network to group different ion species (adducts, in-source fragments, isotopes) originating from the same metabolite. This is based on chromatographic co-elution and peak shape correlation [21].

- This step consolidates the annotation and removes redundancy, ensuring that multiple features from the same metabolite are correctly grouped.

The following diagram visualizes this multi-layer networking strategy.

Diagram 2: Knowledge-Guided Multi-Layer Networking. This diagram shows the interaction between the knowledge-based metabolic reaction network and the data-driven feature network, enabling annotation propagation from known seed metabolites to unknown compounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of metabolomics experiments relies on a foundation of high-quality reagents, standards, and analytical resources. The following table details key materials essential for the workflows described in this article.