Molecular Mechanisms of Natural Products in Inflammation and Cancer: From Pathways to Precision Therapeutics

Chronic inflammation is a critical hallmark and driver of cancer, underlying up to 60% of all deaths worldwide.

Molecular Mechanisms of Natural Products in Inflammation and Cancer: From Pathways to Precision Therapeutics

Abstract

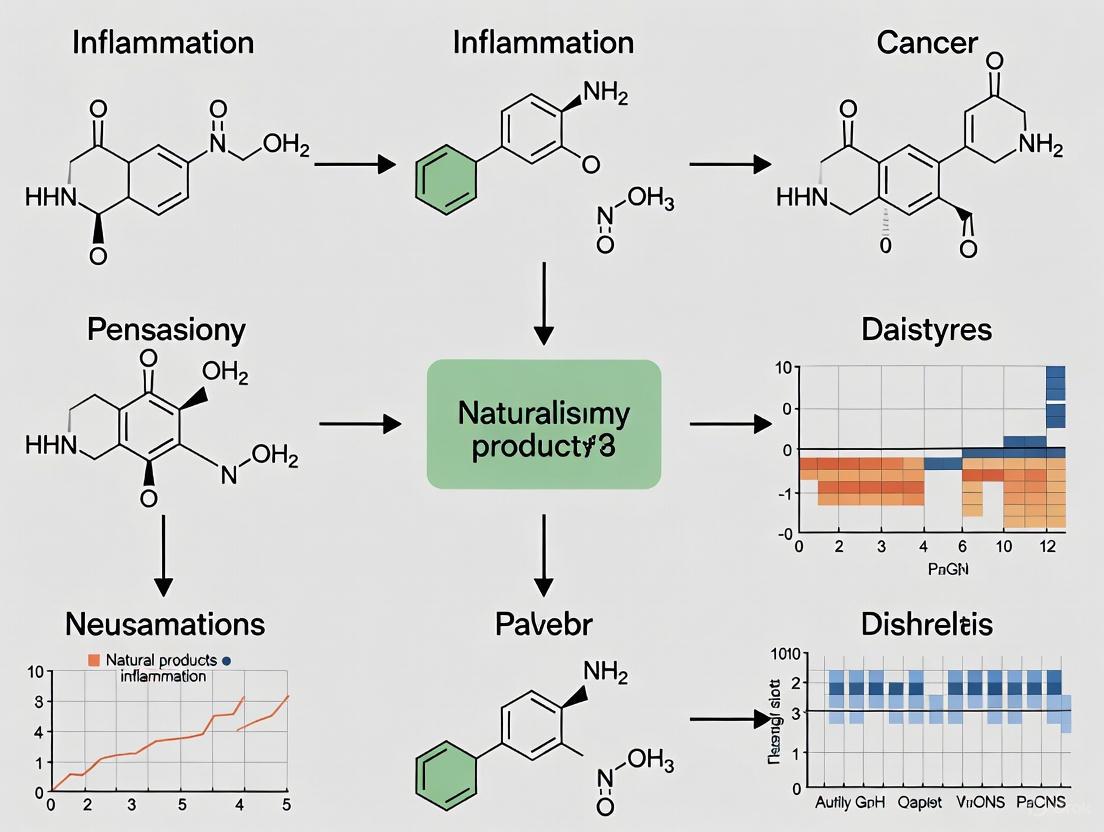

Chronic inflammation is a critical hallmark and driver of cancer, underlying up to 60% of all deaths worldwide. This review synthesizes current evidence on natural products—including sesquiterpenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids—that dually target inflammatory and oncogenic signaling hubs such as NF-κB, STAT3, p53, and MDM2. We explore foundational mechanisms connecting inflammation to tumorigenesis, methodological advances in identifying bioactive compounds, and innovative strategies like nanoparticle delivery to overcome poor bioavailability. The content further validates therapeutic efficacy through preclinical and clinical outcomes, compares natural products with conventional treatments, and discusses their potential as standalone or adjunctive therapies to overcome drug resistance and improve patient outcomes in oncology.

The Inflammation-Cancer Nexus: Unraveling Core Molecular Pathways for Therapeutic Targeting

Linking Chronic Inflammation to Cancer Initiation, Progression, and Metastasis

The link between chronic inflammation and cancer has been recognized since 1863, when German pathologist Rudolf Virchow observed the presence of inflammatory infiltrates in solid tumors and hypothesized that cancer develops at sites of chronic inflammation [1] [2]. Today, cancer-related inflammation is considered a hallmark of cancer, with approximately 25% of all cancers arising from a chronic inflammatory microenvironment [1] [2]. Inflammation affects all stages of cancer, from the initiation of carcinogenesis to metastasis and treatment response [3] [1]. While acute inflammation can stimulate anti-tumor immune responses, chronic inflammation induces immunosuppression, providing a microenvironment conducive to carcinogenesis [3]. This review examines the molecular mechanisms linking chronic inflammation to cancer progression and explores how natural products can target these pathways, providing a comparative analysis of their efficacy and mechanisms of action.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) represents a critical interface where inflammatory processes shape cancer behavior. Solid tumors develop an inflammatory TME containing cancer cells, immune cells, stromal cells, and soluble molecules that collectively determine tumor progression and therapy response [3] [1]. Both cancer cells and stromal cells within the TME display remarkable plasticity, constantly changing their phenotypic and functional properties in response to inflammatory signals [1]. Cancer-associated inflammation, predominantly composed of innate immune cells, plays a pivotal role in cancer cell plasticity, progression, and the development of anticancer drug resistance [1]. Understanding these dynamic interactions provides the foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies that harness natural products to modulate inflammatory pathways in cancer.

Molecular Mechanisms Linking Inflammation to Cancer

Key Signaling Pathways

Chronic inflammation promotes tumor development through multiple interconnected signaling pathways that regulate cell survival, proliferation, and immune evasion. The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway serves as a central regulator of inflammation-associated cellular transformation [1] [2]. Activated by oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines, NF-κB initiates transcription of various genes encoding anti-apoptotic proteins (BCL-XL, BCL-2), cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8), inflammatory enzymes (iNOS and COX-2), matrix metalloproteases (MMPs), cell cycle regulators (c-MYC and cyclin D1), and angiogenic factors (VEGF and angiopoietin) [1] [2]. This diverse transcriptional output explains how NF-κB activation can influence multiple aspects of cancer progression.

The Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway, particularly STAT3, represents another critical signaling node in inflammation-driven cancer [4] [5]. STAT3 activation occurs in response to various cytokines and growth factors in the TME, promoting the expression of genes involved in cell survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis [5]. Additional pathways including toll-like receptors (TLRs), cGAS/STING, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) contribute to the inflammatory network that supports tumor development [4]. These pathways demonstrate extensive crosstalk, creating a robust signaling network that can sustain chronic inflammation even when individual components are inhibited.

Table 1: Key Inflammatory Signaling Pathways in Cancer Development

| Pathway | Primary Activators | Key Downstream Effects | Role in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF-κB | TNF-α, IL-1β, PAMPs, DAMPs | Expression of anti-apoptotic genes, pro-inflammatory cytokines, MMPs, angiogenic factors | Promotes cell survival, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis |

| JAK-STAT | IL-6, IFN, growth factors | Transcription of cell cycle regulators, anti-apoptotic proteins | Enhances proliferation and prevents apoptosis |

| TLR | Pathogen components, DAMPs | Production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines | Connects infection/injury to cancer-promoting inflammation |

| MAPK | Growth factors, cytokines | Cell proliferation, differentiation, survival | Drives cancer cell growth and invasion |

| cGAS-STING | Cytosolic DNA | Type I interferon production | Can have both pro- and anti-tumor effects depending on context |

The Inflammatory Tumor Microenvironment

The tumor microenvironment represents a complex ecosystem where cancer cells interact with various immune and stromal components. Cancer-associated inflammation shapes the cellular composition of the TME by recruiting innate immune cells such as macrophages and neutrophils, along with immunosuppressive cells including myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) [1]. This inflammatory and immunosuppressive TME facilitates immune escape, enabling cancer cells to evade detection and destruction by the immune system [1].

Recent technological advances have revolutionized our understanding of the TME. Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial molecular imaging analysis have elucidated the pathways linking chronic inflammation to cancer with unprecedented resolution [1]. These approaches reveal the remarkable heterogeneity of both cancer and stromal cells within the TME and their dynamic interactions. The composition of the TME varies significantly between cancer types and even between individual patients, highlighting the need for personalized approaches to targeting inflammation in cancer therapy.

Natural Products as Modulators of Cancer-Associated Inflammation

Clinically Established Natural Product-Derived Anticancer Agents

Natural products have contributed significantly to cancer chemotherapy, with several plant-derived compounds serving as cornerstone treatments for various malignancies [6] [7]. These agents typically function through cytotoxic mechanisms that block essential pathways required for cancer cell growth. Vinca alkaloids (vinblastine and vincristine) from Vinca rosea L. inhibit mitosis by binding microtubular proteins, while paclitaxel from Taxus brevifolia bark stabilizes microtubules leading to mitotic arrest [6] [7]. Camptothecin from Camptotheca acuminata and its analogs inhibit topoisomerase I, enhancing DNA damage and apoptosis, while podophyllotoxin from Podophyllum species binds tubulin and inhibits topoisomerase II [7].

Microbial-derived natural products have also made substantial contributions to cancer therapy. Bleomycin, actinomycin D, mitomycin C, doxorubicin, and daunorubicin from Streptomyces species, along with carfilzomib from Actinomyces, represent important classes of anticancer agents [7]. These compounds primarily target DNA through intercalation, alkylation, or strand break induction, while carfilzomib inhibits proteasome function. Despite their efficacy, these natural product-derived drugs are associated with significant toxicity, spurring research into more targeted approaches.

Table 2: Clinically Established Natural Product-Derived Cancer Therapeutics

| Natural Product | Source | Molecular Target | Primary Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vincristine | Vinca rosea L. | Microtubules | Leukemia, Lymphoma |

| Vinblastine | Vinca rosea L. | Microtubules | Hodgkin's Disease, Testicular Cancer |

| Paclitaxel | Taxus brevifolia | Microtubules | Ovarian, Breast, Lung Cancers |

| Camptothecin analogs | Camptotheca acuminata | Topoisomerase I | Colorectal, Ovarian Cancers |

| Podophyllotoxin derivatives | Podophyllum species | Topoisomerase II, Tubulin | Testicular, Lung Cancers, Leukemia |

| Doxorubicin | Streptomyces species | DNA intercalation | Various Solid Tumors, Leukemias |

| Bleomycin | Streptomyces species | DNA strand break induction | Testicular Cancer, Lymphoma |

| Carfilzomib | Actinomyces species | Proteasome | Multiple Myeloma |

Dietary-Derived Natural Products with Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Properties

Beyond the established cytotoxic natural products, numerous dietary compounds demonstrate potential for targeting cancer-associated inflammation. Phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and related phytochemicals exhibit anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities in preclinical models, though their clinical effectiveness has been limited by poor bioavailability and insufficient targeting [7]. The Mediterranean diet, characterized by high intake of fruits, vegetables, nuts, whole grains, olive oil, and moderate consumption of fish, represents a dietary pattern associated with reduced cancer incidence and slower cancer progression [7]. This diet contains numerous bioactive compounds that may collectively modulate inflammatory pathways relevant to cancer.

Research indicates that the clinical effectiveness of dietary natural products can be enhanced through a more targeted approach [7]. This strategy involves identifying critical response genes or pathways in specific cancers and selecting the optimal natural compound to modulate those targets. Promising targets for dietary natural products include non-oncogene addiction genes such as Sp transcription factors, reactive oxygen species (ROS) pathways, and the orphan nuclear receptor 4A (NR4A) sub-family [7]. This mechanism-based precision medicine approach could enhance the clinical efficacy of dietary natural products while minimizing toxic side effects.

Comparative Analysis of Experimental Approaches

In Vitro and In Vivo Models for Studying Inflammation and Cancer

Research into the inflammation-cancer connection employs diverse experimental models, each with distinct advantages and limitations. In vitro systems utilizing cancer cell lines and stromal components enable controlled investigation of specific molecular pathways. Co-culture models incorporating immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, and endothelial cells help recapitulate the complexity of the TME [8]. These systems permit detailed analysis of signaling pathways, cytokine production, and cell-cell interactions underlying inflammation-driven cancer progression.

In vivo models provide essential physiological context for studying the inflammation-cancer axis. Genetically engineered mouse models that develop spontaneous tumors through the activation of inflammatory pathways offer insights into the temporal sequence of events linking inflammation to cancer [8]. Xenograft models incorporating human cancer cells into immunocompromised mice, sometimes with additional human immune components, enable study of human-specific aspects of cancer inflammation. Recently, sophisticated bone marrow models have revealed how chronic inflammation fundamentally remodels the bone marrow microenvironment, allowing mutated stem cell clones to expand and setting the stage for blood cancers [8]. These models demonstrate that inflammatory stromal cells and interferon-responsive T cells create a self-sustaining inflammatory loop that disrupts normal tissue function and supports cancer development.

Assessing the Efficacy of Natural Products Against Cancer-Associated Inflammation

Evaluating the potential of natural products to modulate cancer-associated inflammation requires a multifaceted experimental approach. Molecular docking and pharmacophore modeling facilitate virtual screening of natural compounds against inflammatory targets such as COX-2, NF-κB, and STAT3 [6]. Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling predicts the activity and toxicity of natural product analogs, while molecular dynamics simulations elucidate binding interactions and stability [6]. These computational methods significantly accelerate the drug discovery process, making it more cost-effective and efficient.

Experimental validation progresses from cell-based systems to animal models and ultimately clinical trials. In vitro assays assess the effects of natural products on inflammatory signaling pathways, cytokine production, and immune cell function [6] [7]. In vivo studies evaluate anti-inflammatory and anticancer efficacy in appropriate animal models, examining impacts on tumor growth, metastasis, and tumor-associated inflammation [6]. Promising compounds then advance to clinical trials, which have demonstrated the potential of some natural products but also highlighted challenges related to bioavailability and precise mechanism of action [7]. The transition from computational prediction to clinical application requires careful attention to pharmacokinetic considerations and optimal compound formulation.

Table 3: Experimental Models for Studying Inflammation-Cancer Connection and Natural Product Effects

| Model System | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer cell line cultures | High-throughput screening of compounds, mechanism studies | Reproducible, cost-effective, genetically manipulable | Lack tissue context and immune interactions |

| Co-culture systems | Study of cell-cell interactions in TME | Incorporates multiple cell types, more physiologically relevant | Still simplified compared to in vivo complexity |

| Mouse genetic models | Spontaneous cancer development, prevention studies | Intact immune system, progressive disease modeling | Species differences, expensive and time-consuming |

| Humanized mouse models | Study of human-specific aspects | Human immune components in vivo | Technically challenging, variable engraftment |

| Bone marrow niche models | Clonal hematopoiesis, blood cancers | Reveals microenvironmental contributions | Specialized application, complex analysis |

| 3D organoid cultures | Patient-specific modeling, drug testing | Retains some tissue architecture, personalized approach | Immature cell types, lacks full immune component |

Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Inflammation and Cancer

Cutting-edge research into the inflammation-cancer connection requires specialized reagents and tools. Single-cell RNA sequencing platforms enable comprehensive profiling of the cellular composition and transcriptional states within the tumor microenvironment, revealing how inflammatory signals reshape the TME [1]. Spatial molecular imaging technologies, including multiplexed immunofluorescence and spatial transcriptomics, preserve the architectural context of inflammatory cells within tumors, identifying specialized niches such as tertiary lymphoid structures [1]. These approaches have been instrumental in characterizing inflammatory stromal cells and their role in supporting cancer progression.

Cytokine and chemokine detection systems represent essential tools for quantifying inflammatory mediators in the TME. Multiplex bead-based immunoassays simultaneously measure numerous cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β) and growth factors from limited sample volumes [4]. Reporter cell systems provide functional readouts of pathway activation, with NF-κB, STAT3, and AP-1 reporter lines commonly used to screen natural products for anti-inflammatory activity [4]. Pathway-specific inhibitors, including IKK inhibitors for NF-κB pathway, JAK inhibitors for JAK-STAT pathway, and COX-2 inhibitors for eicosanoid pathway, help establish causal relationships between inflammatory signaling and cancer phenotypes [4] [5].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Inflammation in Cancer

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell analysis platforms | 10x Genomics, Seq-Scope | Characterization of tumor microenvironment heterogeneity, immune cell composition |

| Spatial profiling technologies | Multiplexed immunofluorescence, spatial transcriptomics | Mapping inflammatory niches, cell-cell interactions in tissue context |

| Cytokine detection systems | Luminex, MSD, ELISA | Quantifying inflammatory mediators in tumor tissues, blood, conditioned media |

| Pathway reporter assays | NF-κB, STAT3, AP-1 reporter cell lines | Screening natural products for pathway modulation, monitoring pathway activity |

| Pathway-specific inhibitors | IKK inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, COX-2 inhibitors | Establishing causal roles of specific pathways, combination therapy screening |

| Animal inflammation models | AOM/DSS colitis model, genetically engineered mice | Preclinical evaluation of natural products, studying inflammation-driven carcinogenesis |

| Computational tools | Molecular docking, QSAR, molecular dynamics | Predicting natural product interactions with inflammatory targets, optimizing compounds |

Visualization of Key Signaling Pathways

The NF-κB signaling pathway serves as a central regulator of inflammation-driven cancer progression, integrating signals from various inflammatory mediators. The following diagram illustrates the key components and activation mechanisms of this pathway in the context of cancer development.

NF-κB Pathway in Inflammation-Driven Cancer - This diagram illustrates how inflammatory stimuli activate NF-κB signaling to promote cancer progression through expression of pro-survival genes, inflammatory cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and angiogenic factors.

The transition from normal tissue homeostasis to cancer-supporting chronic inflammation involves multiple cell types and signaling molecules. The following diagram depicts the key cellular and molecular components of the inflammatory tumor microenvironment that drive cancer progression.

TME Remodeling by Chronic Inflammation - This diagram shows how chronic inflammation creates a tumor-promoting microenvironment through immune cell recruitment, stromal activation, and cytokine release, and how natural products can intervene at key points.

The molecular mechanisms linking chronic inflammation to cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis represent promising targets for therapeutic intervention. Natural products offer diverse chemical scaffolds that can modulate inflammatory pathways in the tumor microenvironment, potentially overcoming the limitations of current anti-inflammatory approaches. The future of this field lies in developing mechanism-based precision approaches that match specific natural products to well-defined inflammatory targets in particular cancer contexts [7]. This strategy requires deep molecular characterization of both the inflammatory pathways driving individual cancers and the mechanisms of action of natural products.

Advancing natural products as credible interventions for inflammation-driven cancers will require addressing several challenges. Improving the bioavailability and pharmacokinetic properties of promising compounds through formulation strategies or structural modification represents a critical research direction [7]. Additionally, standardized methods for quantifying and classifying cancer-associated inflammation will enable more consistent evaluation of therapeutic responses [9]. As our understanding of the inflammation-cancer connection deepens, natural products that selectively target pro-tumorigenic inflammation while preserving anti-tumor immunity may become valuable components of comprehensive cancer prevention and treatment strategies.

Transcription factors such as Nuclear Factor kappa-B (NF-κB), Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3), and Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) function as master regulators of fundamental cellular processes, including inflammation, cell survival, proliferation, and metabolism. In pathological states, particularly cancer and chronic inflammatory diseases, these signaling pathways frequently become dysregulated and exhibit extensive crosstalk, creating a robust network that drives disease progression and therapeutic resistance [10] [11]. Traditionally, therapeutic strategies have focused on single-target inhibition. However, the interconnected nature of these pathways often leads to compensatory activation and limited efficacy. Consequently, the emerging paradigm of dual-target inhibition presents a promising strategy to overcome these limitations by simultaneously disrupting multiple nodes within the signaling network [12] [13] [14]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of NF-κB, STAT3, and HIF-1α as dual targets, summarizing experimental data and methodologies that validate this innovative approach, with a specific focus on the molecular mechanisms of natural products.

Mechanistic Insights into Signaling Pathways and Their Crosstalk

NF-κB Signaling Pathway

NF-κB is a transcription factor pivotal in mediating inflammatory responses, cell proliferation, and apoptosis. In the canonical pathway, stimuli such as TNF-α, IL-1, or LPS activate the IKK complex (IKKα, IKKβ, NEMO), which phosphorylates the inhibitory protein IκBα, leading to its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This releases the p65/p50 dimer, allowing its translocation to the nucleus to activate target genes involved in inflammation (e.g., cytokines), survival (e.g., Bcl-xL), and angiogenesis (e.g., VEGF) [10] [15]. The non-canonical pathway, activated by signals like BAFF or CD40L, involves NIK-mediated phosphorylation of IKKα homodimers, resulting in the processing of p100 to p52 and the formation of a p52/RelB active complex [10]. NF-κB activation is closely linked to cancer formation, regulating cancer cell proliferation, metastasis, apoptosis, and angiogenesis [12].

STAT3 Signaling Pathway

STAT3 is a key oncogenic transcription factor that, upon activation by cytokines or growth factors, undergoes phosphorylation, dimerization, and nuclear translocation. In the nucleus, it regulates genes controlling cell cycle progression (e.g., Cyclin D1), apoptosis resistance (e.g., Bcl-2, Bcl-xL), and angiogenesis (e.g., VEGF) [13]. Persistent STAT3 activation is a hallmark of many cancers and is associated with increased metastasis and chemo-resistance [13] [14].

HIF-1α Signaling Pathway

HIF-1α is the oxygen-sensitive subunit of the HIF-1 complex. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs), recognized by the von Hippel-Lindau protein (pVHL), and targeted for proteasomal degradation [16] [11]. Under hypoxic conditions, PHD activity is inhibited, leading to HIF-1α stabilization. It then dimerizes with HIF-1β (ARNT), translocates to the nucleus, and activates genes promoting angiogenesis (VEGF), glycolytic metabolism (GLUT-1), and cell invasion [16] [11]. HIF-1α is conspicuously overexpressed in many solid tumors and is a strong predictor of poor prognosis [16].

Pathway Crosstalk

These transcription factors do not operate in isolation but engage in extensive crosstalk:

- NF-κB and HIF-1α: NF-κB can induce HIF-1α transcription under certain inflammatory conditions [11]. Conversely, hypoxia can activate NF-κB, and both factors can co-regulate common target genes like VEGF and IL-8 [10].

- STAT3 and HIF-1α: The PI3K-mTOR signaling pathway can promote HIF-α mRNA expression. Furthermore, STAT3 phosphorylation by mTORC1 in hypoxic environments can induce HIF-1α RNA expression, creating a feed-forward loop [11].

- STAT3 and NF-κB: These pathways can be co-activated by common upstream signals and synergistically regulate pro-survival and inflammatory gene programs.

The following diagram illustrates the core pathways and their primary crosstalk mechanisms.

Comparative Analysis of Dual-Targeting Agents and Experimental Data

The following tables summarize selected natural and synthetic compounds demonstrating efficacy against NF-κB, STAT3, and HIF-1α, along with key experimental findings.

Table 1: Natural Product Inhibitors of NF-κB, STAT3, and HIF-1α Signaling

| Compound | Primary Target(s) | Key Experimental Findings | Molecular Mechanism | Cellular/Animal Models | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) | NF-κB, STAT3 | Inhibits TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation; suppresses STAT3 phosphorylation. | Binds to TNF-α, inhibiting interaction with TNFR; modulates IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling. | Macrophages, synovial fibroblasts, in vivo inflammation models. | [12] |

| Xanthohumol | NF-κB | Differential inhibition of IFN-γ and LPS-activated macrophages. | Suppresses LPS binding to TLR4/MD2 complex. | Macrophage cell lines. | [12] |

| Cryptotanshinone | STAT3 | Inhibits STAT3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. | Binds to STAT3 SH2 domain, disrupting dimerization. | Breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468). | [13] |

| Berberine | HIF-1α | Prevents recurrence of colorectal adenoma; inhibits HIF-1α activity. | Suppresses HIF-1α protein synthesis or stability. | Clinical trial for colorectal adenoma, colorectal cancer models. | [17] |

| Cucurbitacin B | HIF-1α, STAT3 | Inhibits HIF-1α pathway; suppresses STAT3 activation. | Inhibits translational expression of HIF-1α; modulates JAK/STAT3. | Various cancer cell lines. | [17] |

| Wogonin | HIF-1α | Inhibits tumor angiogenesis. | Promotes degradation of HIF-1α protein. | Human bladder cancer cells, colon cancer models. | [17] |

Table 2: Synthetic and Natural Product-Inspired Dual-Target Inhibitors

| Compound / Hybrid | Dual Targets | Key Experimental Findings | Molecular Mechanism | Tested Models (In Vitro/In Vivo) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naphthoquinone-furo-piperidone derivatives (e.g., 16c) | STAT3, NQO1 | IC₅₀: 0.48 μM (MDA-MB-231); 1.52 μM (MDA-MB-468). Inhibits tumor growth in xenograft models. | Inhibits STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation, nuclear translocation; acts as substrate for NQO1 enzyme inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis. | Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell lines, mouse xenograft models. | [13] |

| Isoalantolactone/ Hydroxamic Acid Hybrid (18 NPs) | STAT3, HDAC | Higher antitumor potency than parent IAL and SAHA; forms self-assembled nanoparticles for improved delivery. | Potent dual STAT3/HDAC inhibitor; induces autophagy and apoptosis. | Various cancer cell lines, in vivo tumor models. | [14] |

| Napabucasin | STAT3 | Phase III clinical trials for various solid tumors. | Inhibits STAT3-driven gene transcription; also reported as NQO1 substrate. | Multiple cancer cell lines, clinical trials. | [13] |

Essential Methodologies for Evaluating Dual-Target Inhibition

Assessing Compound Efficacy and Target Engagement

- Cell Viability Assays (MTT/XTT/CellTiter-Glo): Used to determine IC₅₀ values, as shown with compound 16c in MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells (Table 2) [13].

- Western Blotting and Immunofluorescence: Critical for evaluating protein phosphorylation (e.g., STAT3 Tyr705, IκBα), protein levels (e.g., HIF-1α), and subcellular localization (e.g., NF-κB p65, STAT3 nuclear translocation) [13] [16]. For instance, the inhibition of HIF-1α by wogonin was confirmed via Western blotting showing decreased protein levels [17].

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) and Luciferase Reporter Assays: Measure DNA-binding activity of transcription factors (NF-κB, STAT3, HIF-1) and transcriptional activation of their target genes [10] [13].

- Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR): Assesses mRNA expression of downstream target genes (e.g., VEGF, Bcl-xL, Cyclin D1) to confirm functional inhibition of the transcription factor pathways [10] [13].

Investigating Mechanism of Action

- Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): Determines if an inhibitor disrupts protein-protein interactions critical for pathway activation, such as STAT3 dimerization or HIF-1α/p300 binding [13] [16].

- Molecular Docking and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Used to predict and validate direct binding of small molecules to specific domains of the target proteins (e.g., STAT3's SH2 domain, HIF-1α's PAS domain) [13].

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Detection Assays: Employed when investigating NQO1 substrates (e.g., naphthoquinone derivatives), as the compound's activity can induce ROS-mediated DNA damage and apoptosis [13].

In Vivo Validation Models

- Subcutaneous Xenograft Mouse Models: Standard for evaluating antitumor efficacy of dual-target inhibitors. For example, compound 16c significantly inhibited tumor growth in MDA-MB-231 xenograft models [13].

- Pharmacodynamic Analysis: Tumor tissues from xenograft models are analyzed via immunohistochemistry (IHC) or Western blotting to confirm target modulation (e.g., reduced p-STAT3, HIF-1α, or CD31 for angiogenesis) [13] [17].

- Nanoparticle Formulation and Biodistribution Studies: For compounds with delivery challenges, such as the isoalantolactone hybrid 18, self-assembled nanoparticles (18 NPs) can be developed and their tumor accumulation quantified using imaging techniques [14].

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Transcription Factor Pathways

| Reagent / Resource | Primary Function/Application | Specific Example Targets | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway-Specific Agonists & Inhibitors | Control experiments to activate or inhibit pathways for comparative studies. | TNF-α (NF-κB activator); IL-6 (STAT3 activator); CoCl₂ (Hypoxia mimetic, HIF-1α stabilizer); BAY 11-7082 (IKK inhibitor); Stattic (STAT3 inhibitor). | Verify specificity and optimal working concentrations for each cell line. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detect activated (phosphorylated) forms of signaling proteins via Western Blot, IF, IHC. | Phospho-IκBα (Ser32/36); Phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705); Phospho-p65 (Ser536). | Always use total protein antibodies for normalization. |

| Nuclear Extraction Kits | Isolate nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions to study transcription factor translocation. | NF-κB p65, STAT3, HIF-1α nuclear localization. | Ensure rapid processing to prevent protein degradation/deactivation. |

| Transcription Factor Assay Kits | Quantify DNA-binding activity directly from cell extracts. | NF-κB (p65), STAT3, HIF-1 DNA-binding activity. | More quantitative than EMSA; suitable for higher throughput. |

| Luciferase Reporter Plasmids | Measure transcriptional activity of a pathway in live cells. | Plasmids containing promoters with κB, SIE (STAT3), or HRE (HIF) response elements. | Co-transfect with Renilla luciferase for normalization. |

| Recombinant Cytokines/Growth Factors | Stimulate pathways to test inhibitor efficacy in vitro. | Human recombinant TNF-α, IL-6, EGF, VEGF. | Use carrier-free, high-purity grades to avoid non-specific effects. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Stabilize proteins normally degraded by the proteasome, useful for studying HIF-1α and IκBα turnover. | MG-132, Bortezomib. | Can induce ER stress; use short-term treatments. |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Genetically validate targets via gene knockdown. | siRNA against RELA (p65), STAT3, HIF1A, IKK subunits. | Include non-targeting scrambled controls and monitor knockdown efficiency. |

The simultaneous targeting of NF-κB, STAT3, and HIF-1α represents a sophisticated and promising approach to disrupt the resilient signaling networks that underpin cancer and inflammatory diseases. The comparative data and methodologies outlined in this guide underscore the therapeutic potential of dual-target agents, ranging from natural products like cryptotanshinone to rationally designed hybrids like the naphthoquinone-furo-piperidone derivatives and isoalantolactone-based nanoparticles. The success of these strategies hinges on a deep understanding of pathway crosstalk and the utilization of robust experimental protocols to validate multi-faceted mechanisms of action. As the field progresses, the integration of advanced drug delivery systems, such as self-assembling nanoparticles, will be crucial to overcome the pharmacological challenges associated with these potent inhibitors. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise contexts of pathway dominance and developing clinically viable combinations that maximize efficacy while minimizing toxicity, ultimately paving the way for a new generation of multi-targeted therapeutics.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) represents a complex ecosystem where cancer cells interact with various stromal components, immune cells, and signaling molecules. Within this dynamic milieu, the interplay between transcriptional regulators and their targets significantly influences tumor progression, therapeutic resistance, and metastatic potential. Three critical players—p53, MDM2, and NFAT1—form an intricate regulatory network that bridges intracellular stress responses with extracellular environmental cues. p53, famously known as the "guardian of the genome," functions as a potent tumor suppressor transcription factor that activates diverse cellular responses including cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence, and apoptosis in response to stress signals [18] [19]. Its primary negative regulator, MDM2, serves as an oncoprotein that not only promotes p53 degradation but also exerts p53-independent oncogenic functions [20] [18]. NFAT1 (Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells 1), initially characterized in immune cell activation, has emerged as a significant cancer-associated transcription factor that regulates multiple oncogenic processes, including cell proliferation, migration, invasion, angiogenesis, and drug resistance [20] [21]. This comparison guide objectively analyzes the functional roles, regulatory mechanisms, and therapeutic targeting of these three molecular factors within the tumor microenvironment, providing experimental data and methodologies relevant for researchers validating natural product mechanisms in inflammation and cancer research.

Molecular Functions and Regulatory Mechanisms

Functional Roles in Oncogenesis and Tumor Suppression

Table 1: Comparative Functions of p53, MDM2, and NFAT1 in Cancer Biology

| Molecular Feature | p53 | MDM2 | NFAT1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Tumor suppressor [18] | Oncoprotein [20] | Context-dependent oncogene/tumor suppressor [20] [22] |

| Key Domains | Transcription activation, DNA-binding, Tetramerization, Regulatory [18] | p53-binding, Acidic, Zinc finger, RING finger [20] | NFAT homology, Rel homology, Calcineurin docking [23] |

| Subcellular Localization | Nucleus/cytoplasm [18] | Nucleus/cytoplasm [20] | Cytoplasm (resting)/Nucleus (activated) [23] |

| Expression in Cancers | Mutated/inactivated in ~50% of cancers [19] | Amplified/overexpressed in multiple cancers [20] | Overexpressed/activated in solid tumors and hematological malignancies [20] [23] |

| Regulation of Apoptosis | Induces via intrinsic/extrinsic pathways [18] | Inhibits via p53 degradation and direct mechanisms [20] | Variable effects depending on cellular context [20] |

| Cell Cycle Control | G1/S and G2/M arrest via p21 activation [18] | Promotes progression via p53 inhibition [20] | Represses G1/S transition via Cyclin E regulation [22] |

| DNA Damage Response | Master regulator [18] | Feedback regulator of p53 [24] | Limited direct evidence |

| Metastasis & Invasion | Suppresses via inhibition of EMT [19] | Promotes via p53-dependent and independent mechanisms [20] | Promotes via COX-2, synthesis of prostaglandins [21] |

| Angiogenesis Regulation | Inhibits via thrombospondin-1 induction [18] | Promotes (p53-independent) [20] | Promotes via VEGF regulation [20] |

| Metabolic Regulation | Modulates glycolysis, OXPHOS, autophagy [18] | Influences through p53 and other targets [20] | Limited direct evidence |

Regulatory Networks and Feedback Loops

The p53-MDM2 negative feedback loop represents one of the most critical regulatory circuits in cell fate determination. Under normal physiological conditions, p53 activates MDM2 transcription, and the resulting MDM2 protein binds to p53, promoting its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, thereby maintaining low cellular p53 levels [18] [24]. Following cellular stress, particularly DNA damage, post-translational modifications stabilize p53 by disrupting its interaction with MDM2, leading to p53 accumulation and activation of target genes [18]. NFAT1 introduces an additional layer of complexity to this network by directly binding to the MDM2 P2 promoter and transactivating MDM2 expression independent of p53 status [21]. This regulatory triad creates a sophisticated signaling module that integrates diverse environmental cues to determine cellular outcomes.

Table 2: Experimental Evidence from Key Studies

| Experimental Finding | Experimental System | Key Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| NFAT1 activates MDM2 independent of p53 | HCT116 (p53+/+ and p53-/-), PC3, MCF7 cells | NFAT1 overexpression increased MDM2 protein in both p53 wild-type and null cells; Chromatin immunoprecipitation confirmed direct NFAT1 binding to MDM2 P2 promoter | [21] |

| Positive NFAT1-MDM2 correlation in human tumors | Human hepatocellular carcinoma tissues | Significantly higher expression of both NFAT1 and MDM2 in tumor tissues versus adjacent normal liver; Positive correlation between NFAT1 and MDM2 levels in tumor tissues | [21] |

| Feedback loop protects against DNA damage | Mdm2P2/P2 knock-in mice (defective p53-MDM2 feedback) | Feedback-deficient mice showed enhanced p53-dependent apoptosis in hematopoietic stem cells after DNA damage; Increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation | [24] |

| NFAT1 suppresses tumor growth via Cyclin E | CHO cells with inducible NFAT1, NFAT1-deficient mice | NFAT1 induction inhibited cell cycle progression, colony formation, and in vivo tumor growth; NFAT1-deficient B lymphocytes showed hyperproliferation and increased Cyclin E | [22] |

| Dual inhibitor development | Breast and pancreatic cancer models | SP141 inhibitor directly binds MDM2, enhances autoubiquitination and degradation; Suppresses tumor growth and metastasis regardless of p53 status | [20] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay for NFAT1-MDM2 Promoter Binding [21]:

- Cell Culture & Cross-linking: Culture relevant cancer cell lines (e.g., HCT116, PC3). Cross-link proteins to DNA with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at 37°C.

- Cell Lysis & Sonication: Harvest cells in SDS lysis buffer. Sonicate DNA to fragments of approximately 200 base pairs.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate precleared chromatin with antibodies against NFAT1, HA-tag (for transfected NFAT1), or non-specific IgG overnight at 4°C.

- Bead Incubation & Washing: Add Protein G-agarose beads and incubate for 1 hour at 4°C. Wash beads sequentially with low salt, high salt, LiCl immune complex wash buffers, and TE buffer.

- DNA Elution & Analysis: Reverse cross-links and isolate DNA. Analyze by qualitative or quantitative PCR using specific primers flanking the NFAT1-responsive element in the MDM2 P2 promoter (Forward: 5′-ccccccgtgacctttaccctg-3′, Reverse: 5′-agcctttgtgcggttcgtg-3′).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) for DNA-Protein Interaction [21]:

- Protein Extraction: Prepare nuclear extracts from relevant cells (e.g., Jurkat cells) or purify recombinant NFAT1 DNA-binding domain protein.

- Probe Preparation: Design and label biotinylated double-stranded DNA probes containing the wild-type NFAT1 binding sequence from the MDM2 P2 promoter.

- Binding Reaction: Preincubate nuclear extracts or recombinant proteins with poly(dI:dC) to reduce non-specific binding. React with biotin-labeled NFAT1 probe for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Competition Assay: Include 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled wild-type or mutant competitor probes in preincubation to demonstrate binding specificity.

- Gel Electrophoresis & Detection: Separate protein-DNA complexes by non-denaturing 5% PAGE. Transfer to nylon membranes and detect signals using chemiluminescence.

In Vivo Tumor Xenograft Models for Therapeutic Assessment [20] [22]:

- Animal Selection: Utilize immunodeficient nude mice (e.g., 6-8 week old females) for human tumor cell line implantation.

- Cell Inoculation: Harvest exponentially growing cancer cells and resuspend in sterile PBS. Inject subcutaneously into the flanks of mice (typically 1-5×10^6 cells per site).

- Treatment Protocol: Randomize mice into treatment groups once tumors become palpable (~100-150 mm³). Administer test compounds (e.g., SP141, natural products) or vehicle control via appropriate routes (oral, intraperitoneal) at predetermined schedules.

- Tumor Monitoring: Measure tumor dimensions regularly with calipers. Calculate tumor volume using the formula: Volume = (Length × Width²)/2.

- Endpoint Analysis: Euthanize animals at study endpoint. Collect tumors for molecular analyses (Western blotting, IHC, RNA extraction) to confirm target modulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating the p53-MDM2-NFAT1 Axis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | HCT116 (p53+/+ and p53-/-), PC3 (p53 null), MCF7 (breast cancer), Jurkat (T-cell leukemia) | In vitro mechanistic studies, signaling pathway analysis, drug screening | HCT116 isogenic pairs enable p53-specific effect discrimination [21] |

| Expression Plasmids | HA-NFAT1, CA-NFAT1 (constitutively active), DN-NFAT (dominant negative), His-NFAT1-DBD | Gain/loss-of-function studies, promoter-reporter assays, protein interaction studies | CA-NFAT1 lacks regulatory domains for constitutive nuclear localization [21] |

| Promoter-Reporter Constructs | mdm2 P2 promoter luciferase vectors (Luc01, Luc03), mutant NFAT1 binding site promoters | Transcriptional regulation studies, cis-element mapping, signaling pathway activation | Site-directed mutagenesis of NFAT binding site validates direct regulation [21] |

| Antibodies | Anti-NFAT1 (BD Biosciences), anti-p53 (Santa Cruz), anti-MDM2 (Calbiochem), anti-HA (Covance) | Western blotting, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, chromatin immunoprecipitation | Antibody validation in specific applications is crucial for reliability |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Nutlins (MDM2-p53 interaction), SP141 (MDM2 degradation), Cyclosporin A (calcineurin/NFAT pathway) | Pathway inhibition studies, therapeutic validation, combination therapy approaches | Varying specificity and off-target effects require appropriate controls |

| Animal Models | Mdm2P2/P2 knock-in mice, NFAT1-deficient mice, nude/SCID mouse xenograft models | In vivo functional validation, therapeutic efficacy studies, metastasis models | Genetic background considerations essential for experimental design |

Signaling Pathway Visualization

Therapeutic Targeting and Research Implications

The p53-MDM2-NFAT1 network presents compelling targets for cancer therapeutics, particularly in the context of natural product discovery. Several therapeutic strategies have emerged from research on this triad:

MDM2-Targeted Therapies: Multiple small molecule inhibitors that disrupt the p53-MDM2 interaction have been developed, including nutlins, spiroxindoles, and isolindones [20]. These compounds stabilize p53 by preventing its MDM2-mediated degradation, leading to p53 activation and apoptosis in cancer cells retaining wild-type p53. The synthetic small molecule SP141 represents a novel class of MDM2 inhibitor that not only binds MDM2 but also enhances its autoubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, showing efficacy in breast and pancreatic cancer models regardless of p53 status [20].

NFAT1 Inhibition Strategies: While specific NFAT1 inhibitors are less developed than MDM2-targeted compounds, calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine A and FK506 indirectly suppress NFAT1 activation by preventing its dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation [23]. The development of more specific NFAT1 inhibitors represents an active area of investigation, particularly given the dual role of NFAT1 as both a potential oncogene and context-dependent tumor suppressor [22].

Dual-Targeting Approaches: The interconnectedness of these pathways suggests particular promise for dual inhibitors that simultaneously target multiple components. The NFAT1-MDM2-p53 axis provides a rational foundation for designing such multi-target agents, potentially offering enhanced efficacy and reduced resistance compared to single-target approaches [20]. Natural products provide particularly rich sources for such multi-target agents, with compounds like genistein, curcumin, and ginsenosides showing modulatory effects on these pathways [20] [25].

Integration with Natural Product Research: The search for natural products targeting this network aligns with growing interest in multi-target therapies derived from traditional medicine systems. Numerous phytochemicals including apigenin, berberine, curcumin, and resveratrol have demonstrated modulatory effects on p53, MDM2, and NFAT signaling, although their precise molecular targets often require further elucidation [25]. Advanced approaches including AI-guided compound screening, network pharmacology, and improved delivery systems are enhancing the discovery and development of natural product-inspired therapeutics targeting this oncogenic network [26].

The complexity of the p53-MDM2-NFAT1 network underscores the importance of contextual factors in therapeutic targeting, including p53 mutation status, tissue-specific expression patterns, and cross-talk with other signaling pathways. Future research directions should emphasize the development of more specific NFAT1 inhibitors, dual-targeting strategies, and personalized medicine approaches based on molecular stratification of tumors.

Inflammation is a critical biological response, but chronic inflammation is a hallmark of numerous diseases, including cancer, osteoarthritis, and age-related pathologies [27] [28] [29]. Among the key drivers of these processes are the pro-inflammatory cytokines Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), and a broader phenomenon known as the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP). The SASP represents a complex secretome of factors, including cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and proteases, released by senescent cells [30] [28]. Understanding these mediators is crucial for developing therapeutic strategies, particularly those involving natural products, which show promise in modulating these inflammatory pathways. This guide provides a comparative overview of IL-6, TNF-α, and the SASP, detailing their roles, measurement, and inhibition, with a focus on research applications.

The following table compares the core characteristics, functions, and regulatory mechanisms of IL-6, TNF-α, and the SASP.

Table 1: Comparative Profile of Key Inflammatory Mediators

| Feature | IL-6 | TNF-α | SASP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Name | Interleukin-6 | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha | Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype |

| Nature | Single cytokine | Single cytokine | Complex, heterogeneous secretome |

| Major Cellular Sources | Macrophages, T cells, fibroblasts, senescent cells [31] [28] | Primarily macrophages, also T cells, NK cells, senescent cells [28] [32] | Senescent cells (e.g., fibroblasts, endothelial cells) |

| Key Pro-inflammatory Effects | Fever, acute phase protein production, B cell stimulation [31] | Fever, apoptotic cell death, endothelial activation [31] | Chronic inflammation, tissue degradation, immune cell recruitment [30] [28] |

| Role in Cancer | Promotes tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis; associated with poor prognosis [32] | Can promote tumor proliferation or cause cell death; contributes to a pro-tumor microenvironment [32] | Creates a tumor-promoting microenvironment, drives cancer cell invasiveness [28] [32] |

| Role in Aging/Senescence | Core SASP factor; contributes to "inflammaging" and age-related tissue dysfunction [30] [28] | Contributes to "inflammaging" and chronic age-related diseases [28] | Primary driver of age-related chronic inflammation and multiple age-related diseases [30] [28] |

| Key Regulatory Pathways | NF-κB, JAK-STAT [31] [29] | NF-κB, MAPK [29] | NF-κB, p38 MAPK, JAK, cGAS-STING [30] [31] [28] |

| Natural Product Inhibitors | Curcumin [29], Quercetin [27], Resveratrol [27] | Curcumin [29], Quercetin [27], Resveratrol [27] | Curcumin, Quercetin, Resveratrol (modulate overall SASP) [27] |

Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

Data from preclinical and clinical studies highlight the quantitative impact of these mediators and the efficacy of inhibitory compounds.

Table 2: Experimental Data on Mediator Inhibition and Disease Correlation

| Context | Key Findings | Quantitative Data / Effect Size | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aging & Viral Infection | Elderly COVID-19 patients show elevated serum IL-6 & TNF-α vs. young patients. | Significant elevation in cytokine levels. | [31] |

| Curcumin in Macrophages | Curcumin reduces pro-inflammatory mRNA in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. | ↓ mRNA of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF; optimal effect at 125 μg/mL. | [29] |

| Phytonutrients (In Vitro) | Quercetin and Curcumin reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines. | Reduction of IL-6, TNF-α by >50% in vitro. | [27] |

| Resveratrol (Animal Model) | Resveratrol modifies NF-κB/PI3K/AKT pathways to reduce tumors. | Decreased tumor mass by 60–70%. | [27] |

| SASP & Clinical Aging | Specific SASP proteins in circulation correlate with aging traits and chronic disease. | Strong associations with age, disease, and mortality. | [30] |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Analysis

Accurate measurement is fundamental to research in this field. The methodologies below are standard for quantifying these inflammatory mediators and their effects.

Measuring Cytokines and SASP Components

The SASP and its components can be quantified at the RNA, protein, and functional levels from various sample types, including cell culture supernatants, tissues, and systemic fluids like plasma [30].

Table 3: Key Methodologies for SASP and Cytokine Measurement

| Level of Analysis | Technique | Sample Type | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA | Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) | Cell culture, tissue | Targeted quantification of IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β mRNA [30] [31] |

| RNA | RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) | Cell culture, tissue | Unbiased profiling of the entire transcriptome; SASP Atlas [30] |

| Protein | ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) | Cell culture, plasma, serum | Quantify specific proteins (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) in a sample [30] [31] |

| Protein | Western Blotting | Cell culture, tissue lysate | Detect and semi-quantify specific proteins (e.g., IL-1α, MMPs) and protein modifications [30] |

| Protein | Multiplex Immunoassays (Luminex, MSD) | Cell culture, tissue, plasma | Simultaneously quantify multiple cytokines/chemokines in a small sample volume [30] |

| Protein | Mass Spectrometry | Cell culture, plasma, serum | Discovery-based profiling of the entire secretome [30] |

| Localization | Immunohistochemistry (IHC)/Immunofluorescence (IF) | Tissue sections (FFPE), cells | Spatial detection of proteins (e.g., IL-6) within a tissue architecture [30] |

In Vitro Senescence Induction and SASP Analysis

A common workflow for studying the SASP involves inducing senescence in vitro, followed by validation and analysis of the secretome.

Diagram 1: In vitro SASP analysis workflow.

In Vitro Validation of Natural Product Efficacy

The anti-inflammatory effects of natural products like curcumin are often first validated in cell models, such as LPS-stimulated macrophages.

Diagram 2: Macrophage-based anti-inflammatory assay.

Core Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The pro-inflammatory actions of IL-6, TNF-α, and the SASP are orchestrated by a network of key intracellular signaling pathways.

The NF-κB Pathway: A Central Regulator

The NF-κB pathway is a master regulator of inflammation and is critically involved in the expression of IL-6, TNF-α, and many SASP components [31] [28] [29].

Diagram 3: NF-κB pathway in inflammation and senescence.

Network of Interconnected Pathways

Beyond NF-κB, other major pathways form an integrated network that controls inflammatory and SASP responses, and are common targets of natural products.

Diagram 4: Core inflammatory signaling network.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table catalogs key reagents and their applications for studying these inflammatory mediators, as evidenced in the search results.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| RAW 264.7 Cell Line | A murine macrophage cell line used for in vitro modeling of inflammatory responses. | LPS-induced inflammation model to test anti-inflammatory compounds like curcumin [29]. |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | A potent inflammatory stimulant derived from bacterial cell walls. | Used to induce a robust pro-inflammatory response (IL-6, TNF-α, NO) in macrophage cultures [29]. |

| Senolytic Agents (e.g., ABT-263) | Small molecule drugs that selectively induce apoptosis in senescent cells. | Validating the role of senescent cells in disease models (e.g., reducing SASP-driven inflammation in aged mice) [31]. |

| NF-κB Pathway Inhibitor (e.g., SC75741) | A chemical inhibitor that blocks the NF-κB signaling pathway. | Mechanistic studies to confirm NF-κB's role in SASP expression or virus-induced inflammation [31]. |

| ELISA Kits (IL-6, TNF-α) | Immunoassays for precise quantification of specific cytokine protein levels in samples. | Measuring cytokine concentration in cell culture supernatant, plasma, or serum [30] [31]. |

| Luminex/MSD Multiplex Panels | Bead- or electrochemiluminescence-based assays to measure multiple cytokines simultaneously. | Comprehensive profiling of SASP factors or inflammatory panels from small-volume samples [30]. |

| Antibodies for IHC/IF/Western (p16, p21, SA-β-Gal) | Detection tools for senescence and inflammatory markers. | Validating senescence induction in cells or visualizing senescent cells in tissue sections [30] [31]. |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Kits for RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and quantitative PCR. | Quantifying mRNA expression levels of SASP factors and inflammatory cytokines [30] [31] [29]. |

IL-6, TNF-α, and the broader SASP are central, interconnected mediators in chronic inflammation, cancer, and aging. Robust experimental frameworks exist for their study, ranging from specific cytokine measurements to complex secretome analysis. The NF-κB pathway emerges as a critical nexus regulating all three mediators. Natural products demonstrate significant potential for multi-target inhibition of these inflammatory pathways, supported by quantitative data from pre-clinical models. This comparative guide provides a foundation for researchers to select appropriate methodologies and reagents for their investigations into these key molecular players.

Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Applications of Bioactive Natural Compounds

This guide provides an objective comparison of three major classes of natural products—sesquiterpenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids—focusing on their validated molecular mechanisms in inflammation and cancer research. It is designed to assist researchers and drug development professionals in evaluating the therapeutic potential and experimental evidence for these compounds.

Comparative Analysis of Anticancer and Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms

The table below summarizes the primary mechanisms of action, key signaling pathways, and representative compounds for each natural product class, based on recent preclinical research.

| Natural Product Class | Key Anticancer Mechanisms | Key Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms | Primary Signaling Pathways Targeted | Representative Compounds (Source Organisms) | Example Experimental Data (In Vitro) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sesquiterpenoids | Induces apoptosis, targets cancer stem cells, inhibits cell proliferation, arrests cell cycle [33] [34] [35] | Inhibits NF-κB activation, reduces production of inflammatory mediators (e.g., NO, TNF-α, IL-6) [33] [36] | NF-κB, PI3K/Akt, STAT3, ROS-mediated pathways [33] [34] | Parthenolide (Tanacetum parthenium) [33], Nerolidol (various floral plants) [34], Alantolactone (Inula species) [35] | Parthenolide induced apoptosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells [33]; Compound 9 inhibited NO production in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells by 84.7% at 10 μM [36] |

| Flavonoids | Induces apoptosis, inhibits cell cycle progression, suppresses angiogenesis, reverses drug resistance [37] [38] [39] | Modulates inflammatory cytokines, acts as an antioxidant, inhibits COX-2 [37] [38] | PI3K/Akt/mTOR, Wnt/β-catenin, EGFR/ERK/MAPK, NF-κB [37] [38] [39] | Quercetin (Herba Patriniae, fruits) [37] [39], Apigenin (Herba Patriniae) [37], Luteolin (Herba Patriniae) [37] | Quercetin (0.5% diet) inhibited intestinal lesions in an AOM-induced CRC mouse model; Apigenin (0.1% diet) reduced high-magnitude ACF by 57% [37] |

| Alkaloids | Induces apoptosis via mitochondrial/ROS pathways, arrests cell cycle, inhibits angiogenesis, modulates autophagy [40] [38] | Inhibits NF-κB, exhibits antioxidant activity to reduce oxidative stress [40] [38] | Wnt/β-catenin, STAT3/Snail-EMT, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, NF-κB, Nrf2/Keap1 [40] | Piperine (Black pepper) [40], Berberine (Berberis cretica) [40] [38], Neferine (Nelumbo nucifera) [40] | Piperine induced G0/G1 and S phase cell cycle arrest in colorectal cancer cells; Neferine induced ROS generation and cytochrome c expression in cervical cancer [40] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

To facilitate replication and further investigation, here are the detailed methodologies from pivotal studies cited in this guide.

Protocol: In Vitro Anti-inflammatory Assay for Sesquiterpenoids

This protocol is adapted from the study that identified seco-sativene-type sesquiterpenoids from Bipolaris sorokiniana [36].

- Cell Line: RAW264.7 murine macrophage cells.

- Inflammation Induction: Cells are treated with Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to stimulate an inflammatory response.

- Intervention: Co-treatment of LPS with the test sesquiterpenoid compounds at various concentrations (e.g., 10 µM).

- Key Metabolite Measurement: After a specified incubation period, the concentration of Nitric Oxide (NO) in the culture supernatant is quantified using the Griess reagent method. This measures the accumulation of nitrite, a stable oxidative product of NO.

- Data Analysis: The percentage inhibition of NO production is calculated by comparing the nitrite levels in compound-treated groups against the LPS-only control group.

Protocol: In Vivo Efficacy Study for Flavonoids in Colorectal Cancer

This protocol summarizes the methodologies used to evaluate flavonoids from Herba Patriniae in preclinical models of Colorectal Cancer (CRC) [37].

- Animal Models:

- Chemically-Induced Model: Mice are administered Azoxymethane (AOM) to induce CRC. The development of precancerous lesions, known as Aberrant Crypt Foci (ACF), is a key endpoint.

- Genetic Model: APCMin/+ mice, which spontaneously develop intestinal tumors, are used.

- Intervention: Mice are fed a diet supplemented with a specific flavonoid (e.g., 0.5% quercetin or 0.1% apigenin) over a period of several weeks.

- Endpoint Analysis:

- Tumor Burden: The number and size of intestinal tumors are counted.

- Histopathology: Immunohistochemical staining for markers like Ki67 (proliferation) and LGR5 (cancer stem cells) is performed.

- Biochemical Analysis: Measures of oxidative stress (e.g., lipid peroxidation) and antioxidant defense levels in intestinal tissue.

Protocol: Assessing Multi-Target Anticancer Activity of Alkaloids

This protocol is based on studies investigating the mechanisms of piperidine alkaloids like piperine in colorectal cancer [40].

- Cell Viability and Cytotoxicity: Treated cancer cells (e.g., colorectal cancer cell lines) are analyzed using MTT or WST-1 assays to determine IC50 values.

- Apoptosis Detection:

- Mitochondrial Pathway: Assess changes in mitochondrial membrane potential using JC-1 dye.

- ROS Measurement: Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species levels are measured using fluorescent probes like DCFH-DA.

- Caspase Activation: Activity of executioner caspases (e.g., caspase-3/7) is measured with luminescent or fluorescent substrates.

- Cell Cycle Analysis: Treated cells are stained with propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the distribution in cell cycle phases (e.g., G0/G1, S, G2/M).

- Western Blotting: Protein expression levels in key pathways (e.g., PI3K/Akt/mTOR, Wnt/β-catenin) are analyzed to confirm mechanistic targets.

Visualizing Key Signaling Pathways

The diagram below illustrates the complex interplay of signaling pathways targeted by sesquiterpenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids in the context of cancer and inflammation, highlighting areas of overlap and unique intervention points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents and their applications for studying the molecular mechanisms of these natural product classes.

| Research Reagent | Primary Function in Experimental Protocols | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) [36] | Induces a robust inflammatory response in immune cells like macrophages. | In vitro anti-inflammatory assays; studying NF-κB and cytokine signaling. |

| RAW264.7 Murine Macrophage Cell Line [36] | A standard, readily available cell model for screening anti-inflammatory compounds. | Measuring inhibition of NO and prostaglandin production; cytokine profiling. |

| Azoxymethane (AOM) [37] | A chemical carcinogen used to reliably induce colorectal tumors in rodent models. | In vivo studies on chemoprevention and efficacy against colorectal cancer. |

| APCMin/+ Mouse Model [37] | A genetic model that spontaneously develops numerous intestinal adenomas. | Studying natural product effects on tumor initiation and progression in vivo. |

| Griess Reagent [36] | A chemical assay that quantifies nitrite concentration, a stable product of NO. | Quantifying NO production as a direct readout of inflammatory response in cell cultures. |

| JC-1 Dye [40] | A fluorescent carbocyanine dye that accumulates in mitochondria, used to measure mitochondrial membrane potential. | Detecting early-stage apoptosis induced by compounds via the mitochondrial pathway. |

| DCFH-DA Probe [40] | A cell-permeable fluorescent probe that is oxidized by ROS to a highly fluorescent product. | Measuring intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in treated cells. |

The validation of molecular mechanisms for natural products represents a cornerstone in modern pharmacology, bridging traditional medicine and contemporary drug discovery. This guide provides a systematic comparison of four prominent natural compounds—curcumin, resveratrol, quercetin, and thymoquinone—focusing on their mechanistic validations in inflammation and cancer research. These polyphenolic and quinone compounds exhibit multi-targeted actions against key pathological processes, including oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, oncogenic signaling, and apoptotic resistance. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding their distinct and overlapping molecular pathways, supported by experimental data, is crucial for developing targeted therapies, combination treatments, and overcoming limitations such as poor bioavailability. This analysis synthesizes current evidence from preclinical studies, highlighting both established mechanisms and emerging targets to inform future research directions and clinical translation.

The table below provides a comparative overview of the primary molecular targets, mechanisms of action, and key physiological effects of curcumin, resveratrol, quercetin, and thymoquinone in the context of inflammation and cancer.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Natural Compounds' Molecular Mechanisms

| Compound | Primary Molecular Targets | Key Mechanisms in Cancer | Key Mechanisms in Inflammation | Experimental Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | NF-κB, Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, Nrf2, DNMTs [41] [42] [43] | Induces apoptosis, cell cycle arrest (G2/M), inhibits proliferation & metastasis, epigenetic modulation (DNA demethylation) [41] [43] | Inhibits NF-κB, COX-2; activates Nrf2 antioxidant pathway [42] | In vitro (HepG2, HCT116, MCF-7 cells); in vivo rodent models [41] [42] |

| Resveratrol | SIRT1, VDAC1, NF-κB, p53, AMPK [44] [45] [46] | Induces apoptosis via VDAC1 oligomerization, activates p53, cell cycle arrest, inhibits angiogenesis [46] | Activates SIRT1, inhibits NF-κB and COX-2, reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines [44] [45] | In vitro (SH-SY5Y, HeLa, HEK-293 cells); aged Wistar rat models [44] [46] |

| Quercetin | iNOS, COX-2, PCNA, β-catenin [47] | Reduces tumor incidence, inhibits cell proliferation (PCNA), ameliorates crypt lesions [47] | Alleviates inflammation and oxidative stress (modulates iNOS, COX-2) [47] | In vivo rodent models of colorectal cancer (meta-analysis) [47] |

| Thymoquinone | p53, Bax/Bcl-2, ROS, cell cycle regulators (p21, p27) [48] [49] | Induces apoptosis (↑Bax, ↓Bcl-2), cell cycle arrest (G1/S), increases oxidative stress [49] | Exhibits antioxidant (↑TAS, ↓TOS) and anti-inflammatory properties [48] | In vitro (H1650, MCF-7, HCT116 cells); in vivo xenograft models [48] [49] |

The following table summarizes quantitative data from experimental studies, providing a comparative view of the efficacious concentrations, doses, and key biological effects for each compound.

Table 2: Summary of Quantitative Experimental Data

| Compound | Efficacious Concentration (In Vitro) | Effective Dose (In Vivo) | Key Quantitative Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | IC~50~ ~5-50 µM (cell type-dependent) [41] [42] | 5 mg topical (in Vaseline cream) [42] | ↑Nrf2, HO-1, SOD; ↓NF-κB [42] |

| Resveratrol | Varies by cell type; induces VDAC1 oligomerization [46] | Studied in aged rat models [44] | ↑SIRT1, CD4+ T cells; ↓ROS, IL-6 [44] [45] |

| Quercetin | Meta-analysis of in vivo studies [47] | Varies across rodent studies [47] | ↓ACF incidence (SMD: -1.22), ↓PCNA (SMD: -8.22) [47] |

| Thymoquinone | IC~50~ 26.59 µM (H1650 cells at 48h) [48] | Reduces tumor size in PDAC xenografts [49] | ↓TOS, ↑TAS; ↑Bax/Bcl-2 ratio [48] [49] |

Detailed Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Curcumin: A Multi-Targeted Epigenetic Modulator

Curcumin exerts its effects through pleiotropic interactions with numerous signaling pathways. It directly inhibits the NF-κB pathway, a key regulator of inflammation and cell survival, thereby reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and anti-apoptotic genes [42]. In cancer, curcumin modulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by reducing Axin2 expression and promoting β-catenin degradation, disrupting critical processes for tumor progression like proliferation and stemness [41]. Its epigenetic influence is particularly notable; curcumin inhibits DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), leading to the demethylation and reactivation of silenced tumor suppressor genes. It also modulates histone acetylation and methylation balances, restoring normal chromatin accessibility and gene expression profiles [43]. Furthermore, curcumin activates the Nrf2/ARE axis, a primary cellular defense system, by modifying Keap1's thiol groups, which stabilizes Nrf2 and allows its nuclear translocation to upregulate antioxidant enzymes like HO-1 and SOD [42]. Its effects are highly dose-dependent, ranging from antioxidant at low concentrations (≤1 µM) to autophagy induction at moderate doses (5–10 µM) and promotion of apoptosis at higher levels (≥25 µM) [42].

Resveratrol: Sirtuin Activation and Mitochondrial Apoptosis

Resveratrol's mechanism is characterized by its ability to promote cell survival in normal contexts while inducing death in cancerous ones. A central target is SIRT1, an NAD⁺-dependent deacetylase. Resveratrol's activation of SIRT1 deacetylates and thereby inhibits the p65 subunit of NF-κB, leading to downregulation of inflammatory responses [45]. It also regulates the SIRT1/AMPK/PGC-1α pathway, enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis and reducing oxidative stress [44] [45]. A novel and critical target identified for its pro-apoptotic action in cancer is the mitochondrial protein VDAC1. Resveratrol directly interacts with VDAC1, promoting its overexpression and oligomerization. These oligomeric channels facilitate the release of pro-apoptotic proteins like cytochrome c from the mitochondrial intermembrane space, triggering programmed cell death [46]. This process is further amplified by resveratrol-induced elevation of intracellular Ca²⁺ and ROS levels, as well as the detachment of hexokinase from VDAC1, which disrupts cancer cell metabolism [46].

Quercetin: Targeting Inflammation and Proliferation in Colorectal Cancer

Quercetin's anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory properties are evidenced by significant outcomes in preclinical models of colorectal cancer (CRC). A recent meta-analysis of animal studies confirmed that quercetin treatment significantly reduces the incidence of CRC and alleviates precancerous lesions, such as aberrant crypt foci (ACF) [47]. Its mechanism involves the inhibition of proliferative markers, most notably a profound reduction in PCNA expression, indicating a suppression of tumor cell proliferation [47]. As an anti-inflammatory agent, quercetin alleviates inflammation and oxidative stress by modulating key mediators like iNOS and COX-2 [47]. It also impacts the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, a frequent driver of colorectal carcinogenesis [47].

Thymoquinone: Modulating Apoptosis and Oxidative Balance

Thymoquinone (TQ) demonstrates a multi-faceted mechanism that selectively targets cancer cells. A core function is the induction of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. TQ upregulates the tumor suppressor p53 and alters the balance of Bcl-2 family proteins, increasing pro-apoptotic Bax while decreasing anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. This shift promotes mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, leading to caspase activation and cell death [49]. TQ also induces cell cycle arrest by upregulating inhibitors like p21 and p27 and blocking the activation of cyclins [49]. In lung adenocarcinoma H1650 cells, TQ exhibited a dose-dependent antiproliferative effect and significantly improved the cellular redox balance by decreasing the total oxidant status (TOS) and increasing the total antioxidant status (TAS) [48]. This ability to modulate oxidative stress, coupled with its pro-apoptotic activity, underpins its therapeutic potential.

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol for Assessing Anti-Proliferative Activity (MTT Assay)

The MTT assay is a standard colorimetric method for evaluating cell viability and proliferation.

- Objective: To determine the anti-proliferative effect and calculate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) of a compound (e.g., Thymoquinone on H1650 lung cancer cells) [48].

- Materials: Cell line of interest, RPMI 1640 culture medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin, Thymoquinone, MTT reagent, DMSO, 96-well plate, microplate reader.

- Procedure:

- Seed cells in a 96-well plate at a density of 2 x 10⁴ cells per well and incubate for 24 hours.

- Prepare serial dilutions of the test compound (e.g., TQ at 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µM) and treat the cells for the desired duration (e.g., 48 hours).

- Add MTT solution to each well and incubate for 2-4 hours to allow formazan crystal formation.

- Carefully remove the medium and dissolve the formed formazan crystals in DMSO.

- Measure the absorbance at 570 nm using a microplate reader.

- Calculate cell viability percentage:

(OD_treated / OD_control) x 100. Plot viability against compound concentration to determine the IC₅₀ value [48].

Protocol for Evaluating Apoptosis (Annexin V/PI Staining and Flow Cytometry)

This protocol distinguishes between early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells.

- Objective: To quantify resveratrol-induced apoptotic cell death in SH-SY5Y and HeLa cell lines [46].

- Materials: Cultured cells, resveratrol, Annexin V-FITC conjugate, Propidium Iodide (PI), binding buffer, flow cytometer.

- Procedure:

- Treat cells with varying concentrations of resveratrol for a specified time.

- Harvest cells, wash with PBS, and resuspend in Annexin V binding buffer.

- Add Annexin V-FITC and PI to the cell suspension and incubate for 15-20 minutes in the dark.

- Analyze the stained cells immediately using a flow cytometer.

- The populations are identified as: Annexin V⁻/PI⁻ (viable), Annexin V⁺/PI⁻ (early apoptotic), Annexin V⁺/PI⁺ (late apoptotic), and Annexin V⁻/PI⁺ (necrotic) [46].

Protocol for Analyzing Oxidative Stress Markers

This protocol assesses the compound's impact on the cellular redox balance.

- Objective: To measure the effect of TQ on total antioxidant status (TAS) and total oxidant status (TOS) in H1650 cells [48].

- Materials: Cell lysates, TAS and TOS commercial kits (Rel Assay Diagnostics), microplate reader.

- Procedure for TAS/TOS:

- Prepare cell lysates from treated and control groups.

- For TAS, the assay is based on the bleaching of a colored radical (ABTS⁺) by antioxidants in the sample. The change in absorbance is measured at 660 nm. A standard of known Trolox equivalent concentration is used for calibration [48].

- For TOS, oxidants in the sample oxidize ferrous ions to ferric ions. The ferric ions form a colored complex with chromogen in an acidic medium, and absorbance is measured at 530 nm. The results are expressed in terms of µmol H₂O₂ equivalent per liter [48].

- The Oxidative Stress Index (OSI) is calculated as:

OSI = [(TOS, µmol H₂O₂ Eq/L) / (TAS, µmol Trolox Eq/L)] x 100[48].

Visualization of Core Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the central apoptotic pathway shared by several of these compounds, particularly highlighting resveratrol's interaction with VDAC1.

Diagram 1: Core Mitochondrial Apoptosis Pathway Targeted by Natural Compounds. Resveratrol directly promotes VDAC1 oligomerization [46], while Thymoquinone modulates Bax/Bak activation [49]. Curcumin and Quercetin can initiate the pathway upstream via various stimuli.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents and their applications for studying the mechanisms of these natural compounds.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mechanistic Studies

| Reagent / Assay Kit | Primary Research Application | Key Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| MTT Cell Proliferation Kit | Measuring anti-proliferative effects and calculating IC₅₀ values [48]. | Quantifies metabolically active cells; indicator of cell viability. |

| Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Kit | Detecting and quantifying apoptotic cell populations via flow cytometry [46] [49]. | Distinguishes between early/late apoptotic and necrotic cells. |

| TAS/TOS Assay Kits | Evaluating global cellular antioxidant and oxidant status [48]. | Measures overall redox balance; used to calculate Oxidative Stress Index (OSI). |

| VDAC1 Antibody & siRNAs | Investigating mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis, specifically resveratrol's novel target [46]. | Antibody for protein detection; siRNA for gene silencing to confirm target necessity. |

| Nrf2 & NF-κB Reporter Assays | Validating activation or inhibition of these critical antioxidant and inflammatory pathways [45] [42]. | Measures transcriptional activity of target pathways in response to compound treatment. |

| cDNA Synthesis & RT-PCR Kits | Analyzing gene expression changes of targets (e.g., TLRs, Bcl-2, Bax) [48] [49]. | Quantifies mRNA levels to confirm transcriptional regulation by the compounds. |

This comparative guide validates that curcumin, resveratrol, quercetin, and thymoquinone possess robust and multi-targeted molecular mechanisms against inflammation and cancer, supported by consistent preclinical data. Despite promising mechanisms, a significant challenge for all compounds is poor bioavailability, which is being addressed through advanced formulations like nano-encapsulation [43] [49]. Future research must prioritize rigorous pharmacokinetic studies, standardized dosing protocols, and large-scale randomized controlled trials to translate these extensive preclinical findings into effective and reliable human therapies. The integration of these natural compounds into combination therapy regimens represents a particularly promising frontier for enhancing efficacy and overcoming drug resistance in oncology.

Inducing Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest in Cancer Cells