Harnessing Nature's Arsenal: Innovative Strategies to Overcome Antimicrobial Resistance

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) demands a paradigm shift in therapeutic development.

Harnessing Nature's Arsenal: Innovative Strategies to Overcome Antimicrobial Resistance

Abstract

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) demands a paradigm shift in therapeutic development. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging natural antimicrobial agents—from plant extracts and essential oils to antimicrobial peptides and microbial metabolites—to combat multidrug-resistant pathogens. We explore the foundational science behind their mechanisms of action, advanced methodologies for discovery and application, strategies to overcome bioavailability and efficacy challenges, and frameworks for clinical validation. By integrating ethnopharmacology with modern technology like nanotechnology and computational modeling, this review outlines a multidisciplinary roadmap for developing effective, sustainable anti-infective therapies to address one of the most pressing global health challenges of our time.

The AMR Crisis and Nature's Defense Mechanisms: Exploring Diverse Sources and Action Pathways

The Escalating Global Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the most pressing global public health threats of the 21st century, representing a serious challenge to modern medicine, food security, and economic development worldwide [1]. AMR occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites undergo genetic changes over time, rendering standard antimicrobial medicines ineffective and making infections increasingly difficult or impossible to treat [1] [2].

The scale of this crisis is staggering. In 2019 alone, bacterial AMR was directly responsible for 1.27 million global deaths and contributed to an additional 4.95 million deaths [1]. Current estimates indicate that at least 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur annually in the United States, resulting in more than 35,000 deaths [3]. If current trends continue unchecked, AMR could cause up to 10 million deaths annually by 2050, surpassing cancer as a leading cause of mortality worldwide [4] [5].

Table: Global Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance

| Metric | Statistical Burden | Source/Time Period |

|---|---|---|

| Global Direct Deaths | 1.27 million | 2019 [1] |

| Global Associated Deaths | 4.95 million | 2019 [1] |

| U.S. Resistant Infections | 2.8 million | Annual [3] [6] |

| U.S. Direct Deaths | 35,000+ | Annual [3] [6] |

| Projected Annual Deaths by 2050 | 10 million | OECD Forecast [4] [5] |

| Potential Economic Impact | $3.4 trillion GDP loss | by 2030 [1] |

The economic consequences are equally concerning, with the World Bank estimating that AMR could result in US$1 trillion in additional healthcare costs by 2050 and US$1 trillion to US$3.4 trillion in gross domestic product (GDP) losses per year by 2030 [1]. This comprehensive threat undermines many foundational elements of modern medicine, making routine procedures such as surgery, caesarean sections, cancer chemotherapy, and organ transplants significantly riskier [1].

Understanding the Mechanisms of Resistance

How Resistance Develops and Spreads

Antimicrobial resistance is a natural evolutionary process that is dramatically accelerated by human activity [1]. Bacteria and fungi develop resistance through several key mechanisms, which can be inherent or acquired through genetic mutations or horizontal gene transfer [3].

Table: Key Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms

| Resistance Mechanism | Functional Description | Example Pathogens |

|---|---|---|

| Restrict Drug Access | Alter entryways or reduce number of entry points to prevent antimicrobial entry | Gram-negative bacteria [3] |

| Drug Efflux Pumps | Use pumps in cell walls to remove antibiotic drugs that enter the cell | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida species [3] |

| Enzyme Inactivation | Change or destroy antibiotics using specific enzymes that break down the drug | Klebsiella pneumoniae (carbapenemases) [3] |

| Target Modification | Alter antibiotic binding sites so drugs can no longer recognize or bind to targets | E. coli (with mcr-1 gene), Aspergillus fumigatus [3] |

| Metabolic Bypass | Develop new cell processes that avoid using the antibiotic's target pathway | Staphylococcus aureus [3] |

The misuse and overuse of antimicrobials in humans, animals, and agriculture are primary drivers of AMR acceleration [1]. When exposed to antibiotics, bacteria can develop resistance characteristics to escape their effects, and antibiotics simultaneously reduce non-resistant bacterial populations, creating ecological space for resistant strains to multiply and spread [7]. This selection pressure allows resistant microbes to survive and proliferate, passing resistance traits to subsequent generations and to other bacteria through mechanisms like conjugation, transduction, and transformation [8].

Current Resistance Landscape

The World Health Organization monitors global resistance patterns, with alarming trends emerging across multiple pathogen classes. The 2022 Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) report highlights that approximately 42% of E. coli infections are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, while 35% of Staphylococcus aureus infections are methicillin-resistant (MRSA) [1]. Particularly concerning is the rise of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, a common intestinal bacterium showing elevated resistance levels against last-resort antibiotics [1].

The WHO has categorized antibiotic-resistant bacteria into priority groups to guide research and development. The Critical priority group includes carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Enterobacterales, along with third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales [8]. The High priority group encompasses methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE), and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, among others [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Antimicrobial Research

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Natural Antimicrobial Discovery

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Ethanol, methanol, ethyl acetate, n-butanol, aqueous solutions [8] | Extraction of antimicrobial compounds from various plant parts (leaves, bark, flowers, roots) with different polarity specifications |

| Bioactive Compound Classes | Alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, saponins, tannins, terpenoids [8] | Reference standards for isolation, identification, and antimicrobial activity screening; flavonoids constitute ~25% of antioxidant derivatives studied [8] |

| Reference Antimicrobials | Penicillin, ciprofloxacin, carbapenems, fluconazole [4] [7] | Positive controls for susceptibility testing and comparison of natural compound efficacy |

| Bacterial Strains | ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp.) [4] | Target organisms for evaluating natural product efficacy against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates |

| Cell Culture Media | Mueller-Hinton broth/agar, blood agar, specific fungal media [8] | Standardized cultivation of microbial strains for susceptibility testing and biofilm assays |

| Synergistic Enhancers | Berberine, allicin, maggot secretions (defensins, phenylacetaldehyde) [4] | Natural compounds that enhance conventional antibiotic activity and help overcome resistance mechanisms |

| Napsamycin D | Napsamycin D | Napsamycin D is a uridylpeptide antibiotic for research, inhibiting bacterial translocase I. It is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Phaseollidin hydrate | Phaseollidin Hydrate|Phytoalexin|RUO | Phaseollidin hydrate is a fungal metabolite of the phytoalexin phaseollidin. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Natural Antimicrobial Agents: Mechanisms & Research Protocols

Natural Product Mechanisms of Action

Natural antimicrobials derived from plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi offer promising alternatives to conventional antibiotics, often employing multi-target attack strategies that reduce the likelihood of resistance development [4]. These compounds, shaped by millennia of evolutionary pressure, typically target multiple bacterial pathways simultaneously, including cell wall disruption, protein synthesis inhibition, membrane permeabilization, and biofilm interference [4].

Plant-derived compounds represent particularly rich sources of antimicrobial agents. The major classes of phytochemicals with demonstrated antimicrobial activity include tannins, which disrupt microbial membranes and enzyme functions; terpenoids that exhibit membrane-disrupting properties; alkaloids that intercalate with cell DNA or affect metabolic pathways; and flavonoids that damage microbial membranes [9]. These compounds often work synergistically, providing broad-spectrum activity against resistant pathogens.

Animal-derived antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) constitute another important resource. More than 150 antimicrobial peptides have been identified since 1974, primarily functioning by disrupting bacterial plasma membranes via pore formation or ion channel interference [4]. These include alpha-helical peptides like cecropin (effective against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria), cysteine-rich peptides such as insect defensins (targeting Gram-positive bacteria), proline-rich peptides including lebocins (active against bacteria and fungi), and glycine-rich peptides like attacin (specifically effective against Gram-negative bacteria) [4].

Experimental Protocols for Natural Product Evaluation

Protocol 1: Standardized Bioactivity Screening

Purpose: To evaluate the antimicrobial potential of natural extracts against WHO priority pathogens [8].

Methodology:

- Extract Preparation: Prepare plant/animal extracts using solvents of varying polarity (ethanol, methanol, aqueous, ethyl acetate) through maceration or Soxhlet extraction [8].

- Microbial Inoculum Preparation: Standardize microbial suspensions (WHO priority pathogens) to 0.5 McFarland standard (approximately 1.5 × 10^8 CFU/mL) in appropriate broth media [8].

- Susceptibility Testing:

- Employ broth microdilution methods in 96-well plates to determine Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC)

- Use agar well diffusion assays for preliminary activity screening

- Include appropriate controls (media, solvent, reference antibiotics)

- Biofilm Interference Assay: Cultivate biofilms in specific media, treat with sub-MIC concentrations of natural compounds, and quantify biofilm biomass using crystal violet staining or resazurin metabolism assays [4].

- Time-Kill Kinetics: Evaluate bactericidal activity by determining reductions in viable counts over 24 hours at concentrations 1x, 2x, and 4x MIC [4].

Protocol 2: Synergy Testing with Conventional Antibiotics

Purpose: To identify natural compounds that enhance the efficacy of standard antibiotics and potentially reverse resistance mechanisms [4].

Methodology:

- Checkerboard Assay:

- Prepare serial dilutions of natural products and antibiotics in 2D arrays

- Inoculate with standardized microbial suspension

- Calculate Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) indices

- Interpret results: FIC ≤0.5 = synergy; >0.5-4 = additive/indifferent; >4 = antagonism

- Mechanism-Specific Assays:

- Efflux Pump Inhibition: Assess intracellular antibiotic accumulation with/without natural compounds using fluorescent substrates

- β-Lactamase Inhibition: Test natural compounds for enzyme inhibitory activity against purified β-lactamases

- Combination Time-Kill Assays: Evaluate synergistic effects over 24 hours using natural product-antibiotic combinations at sub-inhibitory concentrations [4].

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What criteria should I use to select natural sources for antimicrobial screening? A: Prioritize sources with documented ethnomedical use, taxonomic diversity, and ecological adaptations to pathogen-rich environments [4] [9]. Insect species surviving in polluted environments (e.g., cockroach brains), plants with historical medicinal applications, and microbial extremophiles have yielded promising compounds [4]. Consider sustainable sourcing and taxonomic novelty to maximize discovery potential.

Q2: How can I distinguish true antimicrobial activity from false positives in screening assays? A: Implement multiple control groups including solvent controls, growth controls, and reference antibiotic controls. Confirm activity through dose-response relationships and multiple assay types (diffusion and dilution methods). Beware of interference from pigments, tannins, or non-specific reactivity that may produce false positives in colorimetric assays [9].

Q3: What approaches are most effective for enhancing the bioavailability and stability of natural antimicrobials? A: Nanoparticle encapsulation has demonstrated significant success in improving bioavailability, stability, and targeted delivery of natural compounds [4]. Lipid nanoparticles, polymeric nanocarriers, and nanoemulsions can protect compounds from degradation while enhancing cellular uptake. Additionally, structural modification of promising lead compounds can improve pharmacokinetic properties [4].

Q4: How can I assess the potential for resistance development to natural antimicrobials? A: Conduct serial passage experiments where microbes are repeatedly exposed to sub-inhibitory concentrations of the compound over multiple generations. Monitor for MIC increases and characterize cross-resistance patterns with conventional antibiotics. Natural products with multiple mechanisms of action typically show slower resistance development [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent activity results between assay replicates

- Potential Causes: Non-standardized inoculum density, extract degradation, precipitation in assay media, or microbial contamination.

- Solutions:

- Standardize microbial inoculum using spectrophotometric methods (0.5 McFarland standard)

- Verify extract stability under storage conditions and during assays

- Include precipitation controls and use solubilizing agents if needed

- Implement strict aseptic technique and media sterility checks

Challenge 2: Poor solubility of natural products in aqueous assay systems

- Potential Causes: High lipophilicity of certain phytochemicals (terpenoids, some alkaloids).

- Solutions:

- Use food-grade solubilizers like DMSO (final concentration ≤1%)

- Employ nanoparticle encapsulation to enhance aqueous dispersion

- Prepare prodrugs or salt forms of active compounds

- Use emulsion-based delivery systems

Challenge 3: Difficulty in isolating individual active compounds from complex mixtures

- Potential Causes: Synergistic interactions between multiple compounds, instability during separation, or loss of activity upon isolation.

- Solutions:

- Employ bioactivity-guided fractionation with continuous activity monitoring

- Use orthogonal separation techniques (size exclusion, ion exchange, reversed-phase chromatography)

- Consider that synergistic combinations may be more valuable than single compounds

- Preserve fractions at appropriate temperatures and under inert atmosphere when needed

Challenge 4: Translating in vitro activity to in vivo efficacy

- Potential Causes: Poor pharmacokinetics, rapid metabolism, toxicity at effective concentrations, or failure to reach target site.

- Solutions:

- Implement early ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) screening

- Develop appropriate formulation strategies to enhance bioavailability

- Use relevant infection models that mimic human pathophysiology

- Consider local/topical application for compounds with poor systemic exposure

The escalating burden of antimicrobial resistance demands innovative approaches to antibiotic discovery and development. Natural products offer particularly promising avenues due to their structural diversity, evolutionary optimization, and frequent multi-target mechanisms that reduce resistance development [4]. The integration of traditional knowledge with modern scientific methods—including omics technologies, bioinformatics, and advanced formulation strategies—provides powerful tools for unlocking nature's antimicrobial arsenal [4].

Future research should prioritize several key areas: First, exploring underinvestigated biological sources, particularly extremophiles and organisms with unique defense mechanisms. Second, applying structural biology and synthetic biology approaches to optimize natural scaffold activity and production. Third, developing sophisticated delivery systems that enhance the stability, bioavailability, and targeted delivery of natural antimicrobials [4]. Finally, implementing robust translational pipelines that efficiently move promising compounds from discovery through preclinical development.

The fight against antimicrobial resistance requires a concerted global effort across the One Health spectrum—encompassing human, animal, and environmental dimensions [1]. By leveraging nature's chemical diversity and ingenuity, researchers can develop the next generation of antimicrobial agents needed to address this critical threat to global health.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides for Researchers

This section addresses common challenges faced by researchers in the field of natural antimicrobial discovery and evaluation.

FAQ 1: Why is my natural plant extract showing no zone of inhibition in the disk diffusion assay, despite known antimicrobial properties?

- Potential Cause: The antimicrobial compounds in the extract may not be diffusing effectively through the agar matrix. This can be due to the molecular size or hydrophobicity of the active compounds.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm Extract Preparation: Ensure you are using an appropriate solvent. Crushing plant material in a solvent like ethanol (IDA) is a common method for creating extracts [10]. Verify that the solvent has completely evaporated from the assay disc before placing it on the agar, as residual solvent can interfere [10].

- Try an Alternative Method: Use a well diffusion assay instead, where the liquid extract is placed into a well punched into the agar. This can sometimes be more effective for compounds with poor diffusivity.

- Check Microbial Inoculum: Confirm that the lawn of bacteria was properly prepared and is in the early logarithmic phase of growth. An overly dense or non-viable inoculum will not show clear zones.

- Consider Bioautography: Perform Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) followed by bioautography. This technique separates the components of the crude extract on a TLC plate, which is then overlaid with agar inoculated with the test microbe. This can reveal active compounds that were masked or had poor diffusion in the standard assay [11].

FAQ 2: My natural antimicrobial peptide (AMP) is highly effective in vitro but shows significant toxicity in mammalian cell cultures. How can I proceed?

- Potential Cause: Many natural AMPs function by disrupting microbial cell membranes, which can lack specificity and also damage host eukaryotic cells [4].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Sequence Modification: Investigate sequence-activity relationship (SAR) studies to identify regions of the peptide responsible for toxicity. Consider synthesizing analogs with amino acid substitutions that enhance selectivity for bacterial membranes (e.g., increasing cationicity or amphipathicity) [4].

- Formulation Approaches: Explore drug-delivery systems. Nanoparticle encapsulation has been shown to enhance the bioavailability and activity of natural substances while potentially reducing toxicity by providing a more targeted release [4].

- Check Purity: Confirm that the observed toxicity is not due to contaminants from the isolation process. Use high-purity, synthesized peptides for critical assays.

FAQ 3: How can I distinguish between bactericidal (killing) and bacteriostatic (growth-inhibiting) effects of my natural compound?

- Solution: Perform a Time-Kill Kinetics Assay [11].

- Inoculate a broth culture with the test bacterium.

- Add your natural compound at the predetermined Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and at multiples of the MIC (e.g., 2x, 4x).

- Incubate and withdraw samples at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 hours).

- Plate serial dilutions of each sample onto agar plates to determine the viable cell count (Colony Forming Units per mL, or CFU/mL).

- Interpretation: A bactericidal effect is typically defined as a ≥3-log10 (99.9%) reduction in the CFU/mL compared to the initial inoculum. A bacteriostatic effect is indicated if the CFU/mL remains relatively unchanged from the initial count but does not increase, showing inhibition of growth.

FAQ 4: I am observing high variability and poor reproducibility in my broth microdilution MIC assays. What are the critical control points?

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent inoculum size, degradation of natural compounds in solution, or human error in serial dilution steps.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Standardize Inoculum: Always calibrate the bacterial inoculum using a method like McFarland standards to ensure a consistent starting density (e.g., ~5 x 10^5 CFU/mL in each well) [12].

- Compound Stability: Prepare fresh stock solutions of your natural extract for each assay. If using DMSO, ensure the final concentration in the assay is low (typically ≤1%) and non-toxic to the bacteria.

- Include Controls: Every assay must include:

- Growth Control: Wells with bacteria and media only (no compound).

- Sterility Control: Wells with media only (no bacteria, no compound).

- Compound Control: Wells with compound and media (no bacteria) to check for auto-precipitation or contamination.

- Reference Control: Wells with a standard antibiotic (e.g., ciprofloxacin) to ensure the test system is performing correctly.

- Use Replicates: Perform all tests in at least duplicate or triplicate to account for biological and technical variability.

Standardized Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Natural Antimicrobials

This section provides detailed, citable protocols for key experiments in the field.

Protocol 1: Agar Disc Diffusion Assay for Initial Screening

Principle: Antimicrobial compounds diffuse from a disc into the agar, creating a concentration gradient. The resulting zone of inhibition around the disc reflects the compound's ability to suppress microbial growth [11] [10].

Materials:

- Microbial broth culture (e.g., Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli K12)

- Sterile Petri dishes

- Nutrient agar

- Sterile forceps

- Whatman antibiotic assay paper discs (or sterile filter paper discs)

- Test substances: natural plant extracts, essential oils, synthetic compounds

- Solvent control (e.g., ethanol, water)

Method:

- Prepare Seeded Agar: Melt nutrient agar and cool to ~45°C. Inoculate the agar with a standardized volume of a microbial broth culture (e.g., 100 μL in 15 mL agar). Mix gently and pour into a sterile Petri dish to create a "lawn" of bacteria. Allow to set [10].

- Prepare Discs: Using sterile forceps, soak paper discs in the test solutions (e.g., plant extracts). Remove and allow them to dry on a sterile surface to evaporate the solvent completely [10].

- Apply Discs: Using sterile forceps, place the impregnated discs onto the surface of the seeded agar. Gently press down to ensure full contact. Typically, 4-5 discs can be placed on a standard 90-mm plate, with adequate space between them.

- Incubate and Observe: Incubate the plates inverted for 2-3 days at an appropriate temperature (e.g., 20-25°C or 37°C). Observe without opening the plates. Measure the diameter of the zones of inhibition (including the disc) in millimeters [10].

Protocol 2: Broth Microdilution for Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Determination

Principle: This method determines the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that inhibits the visible growth of a microorganism [12]. It is a cornerstone for quantifying antimicrobial potency.

Materials:

- 96-well microtiter plate with a flat bottom

- Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB)

- Test bacterium in mid-logarithmic phase

- Stock solution of natural antimicrobial

- Multichannel pipette

- Plate reader (for spectrophotometric reading)

Method:

- Prepare Dilutions: In the first well of a row, add CAMHB containing a high concentration of your test compound. Perform a two-fold serial dilution across the row using a multichannel pipette. The final volume in each well should be 100 μL.

- Inoculate: Dilute the bacterial suspension to achieve a concentration of approximately 5 x 10^5 CFU/mL. Add 100 μL of this inoculum to each test well. This brings the final test volume to 200 μL and completes the two-fold dilution series of the compound.

- Incubate: Cover the plate and incubate at 35±2°C for 16-20 hours.

- Determine MIC: The MIC is the lowest concentration of the antimicrobial agent that completely inhibits visible growth of the organism in the microdilution wells as observed with the unaided eye. For enhanced objectivity, the MIC can be determined spectrophotometrically as the lowest concentration that results in ~90% inhibition of growth compared to the growth control well.

The workflow for this quantitative method is outlined in the diagram below.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for the Field

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the evaluation of natural antimicrobials, with their specific functions.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation in Antimicrobial Research |

|---|---|

| Whatman Antibiotic Assay Discs | Small, sterile paper discs used to absorb and evenly deliver a consistent volume of a liquid antimicrobial sample onto an agar surface in diffusion assays [10]. |

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | The standardized, internationally recognized medium for broth dilution susceptibility testing. The adjusted cation concentrations ensure reproducible results for a wide range of antibiotics [12]. |

| Resazurin Dye | An oxidation-reduction indicator used in cell viability assays. Metabolically active cells reduce the blue, non-fluorescent resazurin to pink, fluorescent resaurin. This provides a colorimetric method for determining the MIC, often as a more sensitive alternative to visual inspection [11]. |

| 96-Well Microtiter Plates | The standard platform for high-throughput broth microdilution assays, allowing for the simultaneous testing of multiple compounds or extracts against one or more microbial strains [12]. |

| McFarland Standards | Suspensions of barium sulfate used to visually adjust the turbidity of a bacterial inoculum to a standardized concentration, which is critical for obtaining reproducible results in both dilution and diffusion methods [12]. |

Mechanisms of Action and Resistance: A Researcher's View

Understanding how natural antimicrobials work and how resistance emerges is fundamental to developing them as effective therapies. The search for natural compounds is driven by their often complex mechanisms, which can involve multiple pathways and reduce the likelihood of resistance development compared to single-target synthetic drugs [4].

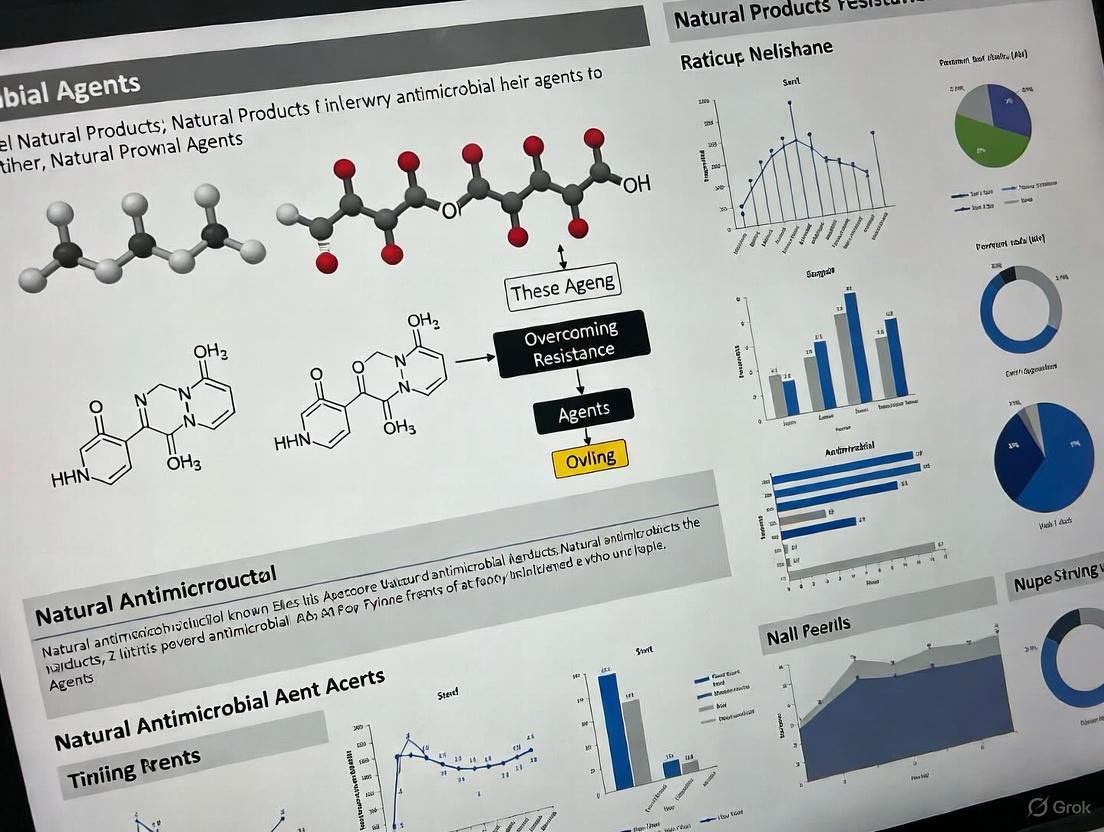

The diagram below illustrates the primary mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, a key challenge that natural antimicrobials must overcome.

Natural antimicrobials can counter these resistance mechanisms in several ways. For instance, they often employ multiple attack pathways, such as simultaneously disrupting bacterial cell membranes and inhibiting protein synthesis [4]. This multi-target action makes it harder for bacteria to develop resistance through simple mutations. Furthermore, some natural compounds, like certain maggot secretions, have been shown to potentiate conventional antibiotics (e.g., ciprofloxacin against MRSA) and slow the development of resistance [4]. Research into antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) from insects and animals explores molecules that disrupt the plasma membrane via pore formation, a mechanism that is difficult for bacteria to combat [11] [4].

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Overcoming Common Research Challenges

Q1: Why are natural antimicrobial agents considered promising for overcoming resistance?

Natural antimicrobial agents often employ multiple mechanisms of action simultaneously, making it more difficult for bacteria to develop resistance compared to single-target conventional antibiotics [4]. These compounds, shaped by millennia of evolutionary pressure, can target bacterial membranes, inhibit protein synthesis, interfere with biofilm formation, and disrupt quorum sensing pathways all at once [4] [14]. This multi-target approach reduces the likelihood of resistance development since bacteria would need multiple concurrent mutations to survive.

Q2: How can I enhance the bioavailability and stability of natural antimicrobial compounds?

Many natural antimicrobial compounds face challenges with stability, absorption, and toxicity [4]. Advanced formulation strategies can address these limitations:

- Nanoparticle encapsulation improves bioavailability, protects compounds from degradation, and enhances targeted delivery [4]

- Combination therapies with conventional antibiotics can create synergistic effects, allowing for reduced doses of both agents while maintaining efficacy [4]

- Chemical modification of natural scaffolds can improve pharmacokinetic properties while maintaining bioactive cores

Q3: What approaches are most effective for discovering novel natural antimicrobials?

Modern discovery pipelines leverage multiple advanced technologies:

- Omics-driven approaches (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) enable high-throughput screening of marine and terrestrial organisms for bioactive compounds [4] [14]

- Bioinformatic tools and databases (such as the Antimicrobial Peptide Database APD3) facilitate in silico identification and optimization of candidate molecules [14]

- CRISPR-based strain engineering can enhance production yields of promising compounds from native producers [4]

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent antimicrobial activity in natural product extracts

| Possible Cause | Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Seasonal variation in source material | Standardize collection time and conditions; use multiple collections | Establish long-term source partnerships; consider cultivated sources |

| Degradation of active compounds during extraction | Optimize extraction parameters (temperature, solvent, time); add stabilizers | Use fresh material; perform extractions under inert atmosphere; store at appropriate conditions |

| Synergistic components missing in purified fractions | Test both crude and fractionated extracts; investigate combination effects | Maintain compound complexity where possible; document complete extraction workflow |

Problem: Limited efficacy against biofilm-forming pathogens

Biofilms represent a significant challenge in antimicrobial research as they can be up to 1000 times more resistant to antimicrobial agents than planktonic cells [14]. Effective strategies include:

- Combine anti-biofilm agents with conventional antibiotics: Some natural compounds can disrupt biofilm structure without killing cells, allowing antibiotics to penetrate better

- Target quorum sensing pathways: Many marine antimicrobial peptides interfere with bacterial communication systems that regulate biofilm formation [14]

- Evaluate persistence: Include persister cell assays in your screening workflow, as these dormant cells within biofilms are particularly resistant to treatment [15]

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluation of Marine-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides

Principle: Marine antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) represent promising candidates due to their structural diversity, membrane-targeting mechanisms, and adaptability to extreme conditions [14].

Materials:

- Test organisms: Include ESKAPE pathogens and reference strains

- Marine AMPs: Isolated from relevant marine organisms

- Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth

- 96-well microtiter plates for MIC determination

Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of marine AMPs in appropriate solvent

- Standardize bacterial inoculum to 0.5 McFarland standard (~1.5 × 10^8 CFU/mL)

- Dilute bacterial suspension to final concentration of 5 × 10^5 CFU/mL in assay medium

- Add 100 μL bacterial suspension to each well containing antimicrobial solution

- Include growth controls and sterility controls

- Incubate at 35°C for 16-20 hours

- Determine MIC as the lowest concentration showing no visible growth

- For biofilm assays, include crystal violet staining or metabolic activity measurements

Troubleshooting:

- If high cytotoxicity observed: Modify peptide sequence to reduce hemolytic activity while maintaining antimicrobial properties

- If poor stability: Consider formulation approaches or structural modifications to enhance half-life

Protocol 2: Assessment of Combination Therapy with Natural Compounds

Principle: Natural compounds can restore sensitivity to conventional antibiotics through synergism, potentially overcoming resistance mechanisms [4].

Materials:

- Test antibiotics representing different classes

- Natural compounds (flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, etc.)

- Bacterial strains with known resistance mechanisms

- Checkerboard template for synergy testing

Procedure:

- Prepare 2x serial dilutions of antibiotic in horizontal direction

- Prepare 2x serial dilutions of natural compound in vertical direction

- Add bacterial suspension to achieve final concentration of 5 × 10^5 CFU/mL

- Incubate at 35°C for 16-20 hours

- Calculate Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) index:

- FIC index = (MIC of antibiotic in combination/MIC of antibiotic alone) + (MIC of natural compound in combination/MIC of natural compound alone)

- Interpret results: FIC index ≤0.5 = synergy; >0.5-4 = additive/indifferent; >4 = antagonism

Troubleshooting:

- If antagonistic effects observed: Re-evaluate combination ratios or select alternative antibiotic partners

- If no synergy detected: Screen additional natural compound classes with different mechanisms of action

Quantitative Data on Antimicrobial Resistance

Global Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance

Table: Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance Worldwide

| Metric | Value | Source/Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| Direct deaths attributable to AMR | 1.27 million annually | Global, 2019 [3] |

| Total deaths associated with AMR | 4.95 million annually | Global, 2019 [5] |

| Projected annual deaths by 2050 | 10 million | O'Neill Report Projection [4] |

| U.S. antimicrobial-resistant infections | 2.8 million annually | CDC 2019 Report [16] |

| U.S. deaths from resistant infections | 35,000+ annually | CDC 2019 Report [16] |

| Healthcare costs for resistant infections | >$4.6 billion annually | U.S. Healthcare System [16] |

Natural Product Efficacy Against Resistant Pathogens

Table: Natural Antimicrobial Compounds and Their Targets

| Compound Class | Source | Key Mechanisms | Target Pathogens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids & Flavonols | Marine plants [17] | Cell membrane disruption; Synergy with antibiotics; Virulence suppression | MRSA, Gram-positive bacteria [17] |

| Terpenoids/Isoprenoids | Marine sponges, algae [17] | Enzyme inhibition; Membrane disruption | Bacillus subtilis, Proteus vulgaris, HIV [17] |

| Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) | Marine organisms, insects, animals [4] [14] | Membrane pore formation; Intracellular target inhibition; Biofilm disruption | MRSA, VRE, ESBL-producing bacteria [14] |

| Alkaloids | Multiple natural sources [17] | Heterogenous mechanisms including enzyme inhibition | Various multidrug-resistant pathogens [17] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Natural Antimicrobial Research

Table: Key Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Marine-derived AMPs | Membrane disruption; biofilm inhibition | Targeting multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria [14] |

| Terpenoid compounds | Enzyme inhibition; membrane targeting | Anti-HIV research; broad-spectrum antibacterial activity [17] |

| Flavonoid extracts | Multi-target mechanisms; antibiotic synergism | Overcoming MRSA resistance; suppressing virulence factors [17] |

| Probiotic strains | Microbiome modulation; pathogen exclusion | C. difficile infection management; gut health restoration [18] |

| Nanoparticle delivery systems | Enhanced bioavailability; targeted delivery | Improving stability of natural compounds [4] |

| Omics technologies | High-throughput compound discovery | Identifying novel bioactive molecules from marine sources [14] |

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

Natural Antimicrobial Discovery Pipeline

Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Compound Sourcing and Characterization

Q: What are the major classes of plant-derived bioactive compounds with demonstrated activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens? A: Research consistently identifies three major classes: terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics (which include flavonoids). These compounds show promise against WHO priority pathogens like MRSA, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa due to their diverse antimicrobial mechanisms [19] [20] [21].

Q: Why is the extraction yield of my target bioactive compound so low and variable? A: Yield variability is common and influenced by several factors [22]:

- Plant Source: The specific plant part (leaves, bark, roots, flowers), its genotype, and the time of harvest significantly affect compound concentration [20].

- Extraction Technique: The choice of solvent (e.g., ethanol, methanol, ethyl acetate, aqueous) is critical, as different compounds have varying solubility [20].

- Environmental Stressors: Plants subjected to biotic (pathogens, insects) or abiotic (drought, UV) stress often produce higher levels of secondary metabolites as a defense mechanism [22].

Q: How can I rapidly screen for compounds that disrupt bacterial communication (Quorum Sensing)? A: Employ reporter-gene assays. These utilize bacterial strains engineered to produce a detectable signal (e.g., luminescence, pigmentation) in response to Quorum Sensing molecules. A reduction in this signal upon introduction of your test compound indicates successful Quorum Sensing inhibition, a known mechanism for terpenoids like cinnamaldehyde and carvacrol [21].

Bioactivity and Mechanism of Action

Q: My isolated compound shows good in vitro antimicrobial activity but fails in subsequent in vivo models. What could be the reason? A: This is a frequent challenge. Key considerations include:

- Pharmacokinetics: The compound may have poor absorption, rapid metabolism, or short half-life in a live model [4].

- Bioavailability: Low stability in the extracellular environment or inability to reach the target site at an effective concentration can cause failure [4].

- Formulation: Advanced delivery systems, such as nanoparticle encapsulation, can enhance stability, bioavailability, and targeted delivery, thereby improving in vivo efficacy [4].

Q: How can I confirm a proposed mechanism of action, such as bacterial membrane disruption? A: A combination of assays provides robust evidence:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Directly visualizes physical damage to bacterial cell membranes [21].

- ATP Release Assays: Measure the leakage of intracellular ATP, indicating loss of membrane integrity [21].

- Potassium Ion Efflux Measurement: Detects the release of potassium ions, another marker of membrane compromise [21].

Q: What does it mean when a plant extract shows stronger antimicrobial activity than its isolated primary compound? A: This often indicates synergistic action. Natural extracts contain a complex mixture of compounds (e.g., terpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids) that can attack multiple bacterial targets simultaneously. For example, carvacrol can damage the outer membrane, making it easier for other compounds like eugenol to enter and exert their effects [21]. This multi-target approach can enhance overall efficacy and reduce the likelihood of resistance development [19].

Quantitative Efficacy Data

Reported Antimicrobial Activity of Key Compound Classes

Table 1: Activity of Terpenoids, Alkaloids, and Flavonoids against Resistant Pathogens

| Compound Class | Example Compounds | Target Resistant Pathogens | Key Antimicrobial Mechanisms | Research Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | 1,8-cineole, Cinnamaldehyde, Carvacrol, Thymol, Eugenol [21] | MRSA, E. coli, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa [21] | Cell membrane destruction, Anti-quorum sensing, Inhibition of ATPase and protein synthesis [21] | A 2025 systematic review identified terpenoids as a principal class effective against WHO priority pathogens [20]. |

| Alkaloids | Berberine, Morphine, Caffeine [22] | MRSA, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE) [19] | DNA synthesis inhibition, Enzyme modification, Plasmid curing, Drug efflux pump inhibition [21] | Demonstrated significant antibacterial qualities and potential for use in combinational therapy with traditional antibiotics [19]. |

| Phenolics/ Flavonoids | Flavonoids, Tannins, Lignans [22] | Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhi [20] | Antioxidant activity, Cell wall disruption, Biofilm interference [22] [4] | Represented 24.8% of antioxidant product derivatives in a recent systematic review, highlighting their significant therapeutic potential [20]. |

Experimental Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Key Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol, Ethanol, Ethyl Acetate | Solvents for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant material [20]. | Used in sequential or single-solvent extraction from dried and powdered plant parts (leaves, bark) [20]. |

| Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) | Positive control for membrane disruption assays [4]. | Serves as a reference standard when testing novel compounds for membrane-permeabilizing effects. |

| Acyl Homoserine Lactone (AHL) | Autoinducer molecule for Quorum Sensing (QS) studies in Gram-negative bacteria [21]. | Used in reporter assays to test the ability of terpenoids (e.g., cinnamaldehyde) to inhibit QS signaling. |

| FtsZ Protein | A prokaryotic tubulin homolog essential for bacterial cell division; a target for inhibitor screening [21]. | Used in in-vitro GTPase activity assays to identify compounds that inhibit bacterial cell division. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Workflow for Bioactive Compound Isolation and Screening

This diagram outlines a generalized protocol for extracting and testing plant-derived bioactive compounds.

Title: Bioactive Compound Isolation Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

- Plant Material Preparation: Collect the desired plant part (e.g., leaves, roots), often from regions with a history of traditional use [20]. Wash, air-dry in the shade, and grind into a fine powder to increase the surface area for extraction [22].

- Solvent Extraction: Subject the powdered material to extraction using a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate) [20]. This can be done via maceration (soaking with agitation) or using a Soxhlet apparatus. The choice of solvent is critical and depends on the polarity of the target compounds.

- Crude Extract Processing: Filter the extract to remove particulate matter. Concentrate the filtrate using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure to obtain a crude dry extract [22].

- Preliminary Bioactivity Screening: Test the crude extract for antimicrobial activity against target multidrug-resistant pathogens using standard assays like Agar Well Diffusion to determine the zone of inhibition and Broth Microdilution to determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) [20].

- Bioassay-Guided Fractionation: Fractionate the active crude extract using chromatographic techniques (e.g., silica gel column chromatography, HPLC). Each fraction is then re-tested for bioactivity. The active fractions are pursued for further purification, ensuring effort is focused on the compounds responsible for the observed activity [21].

- Compound Identification: Purity the active compound(s) to homogeneity. Elucidate the chemical structure using analytical techniques such as Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and Mass Spectrometry (MS) [21].

- Mechanism of Action Studies: Investigate the specific antimicrobial mechanism using specialized assays, as detailed in the following section.

Key Antimicrobial Mechanism Pathways

This diagram visualizes the multi-target mechanisms by which terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics exert their antimicrobial effects.

Title: Multi-Target Antimicrobial Mechanisms

Detailed Methodology for Key Mechanisms:

Cell Membrane Disruption Assay:

- Principle: Measure the release of intracellular components upon membrane damage.

- Protocol: Treat a bacterial suspension (e.g., of E. coli or MRSA) with the MIC of the test compound (e.g., carvacrol). Use a luminometer to measure extracellular ATP concentration or an atomic absorption spectrometer to measure potassium ion (K+) efflux over time. Compare against an untreated control [21].

Quorum Sensing Inhibition Assay:

- Principle: Use a bioreporter strain (e.g., Chromobacterium violaceum or an engineered E. coli) that produces a visible pigment (violacein) or luminescence in response to its native AHL signal.

- Protocol: Grow the bioreporter strain in the presence of sub-inhibitory concentrations of the test compound (e.g., cinnamaldehyde) and its AHL signal. A reduction or absence of pigment/luminescence compared to the control (AHL only) indicates successful Quorum Sensing inhibition [21].

Synergy Testing (Checkerboard Assay):

- Principle: Determine if a combination of a natural compound and a conventional antibiotic has enhanced (synergistic) effects.

- Protocol: In a 96-well microtiter plate, create a two-dimensional dilution series of the antibiotic and the phytochemical. Inoculate each well with a standardized bacterial suspension. After incubation, calculate the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) index. An FIC index of ≤0.5 is generally considered synergistic [19].

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a severe global threat, with drug-resistant infections contributing to millions of deaths annually and projected to cause 10 million deaths per year by 2050 if unaddressed [13]. In this context, natural antimicrobial agents, particularly Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs), have emerged as a promising therapeutic alternative due to their distinct mechanisms of action that can circumvent conventional resistance pathways. AMPs, which are produced by virtually all classes of organisms as part of innate immune responses, combat bacteria through three primary direct mechanisms: membrane disruption, enzyme inhibition, and nucleic acid targeting [23] [24]. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers investigating these mechanisms, with a specific focus on methodologies, troubleshooting, and reagent solutions essential for advancing this critical field of study.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Membrane Disruption Mechanisms

Q1: How can I quantitatively assess whether my candidate antimicrobial peptide disrupts bacterial membranes?

A1: You can employ several well-established biophysical and cell-based assays to detect membrane disruption. The table below summarizes the key methodologies:

Table: Key Methodologies for Assessing Membrane Disruption

| Method | Measured Parameter | Model System | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [23] | Peptide-lipid binding affinity & kinetics | Solid-supported lipid bilayers | Association (k_on)/dissociation (k_off) rate constants; Equilibrium dissociation constant (K_D) |

| Dye Leakage Assay [23] | Membrane permeability | Dye-loaded unilamellar vesicles (e.g., Calcein, Carboxyfluorescein) | Fluorescence increase due to dye release; % membrane disruption |

| NPN Uptake Assay [23] | Outer membrane integrity (Gram-negative) | Bacterial cell suspension | Fluorescence increase (NPN fluoresces in hydrophobic membranes) |

| DiSC3(5) Depolarization Assay [23] | Cytoplasmic membrane depolarization | Bacterial cell suspension | Fluorescence increase upon dye release from depolarized cells |

| Flow Cytometry with Viability Stains [23] | Bacterial membrane integrity | Bacterial cells stained with SYTO 9/PI or SYTOX Green | Population distribution of live vs. dead cells based on membrane integrity |

Q2: My membrane disruption assay results are inconsistent between model liposomes and live bacteria. What could be causing this?

A2: This is a common challenge. Consider these troubleshooting steps:

- Lipid Composition Mismatch: Model membranes may lack the complexity of bacterial membranes. Ensure your liposomes contain key bacterial lipids like phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and cardiolipin [23].

- Cell Wall Barrier: Gram-positive bacteria have a thick peptidoglycan layer that can hinder peptide access, which is absent in liposomes. Pre-treat cells or use protoplasts to test if the wall is the barrier [25].

- Efflux Pumps: Active bacterial efflux systems can expel peptides, reducing their effective concentration at the membrane. Use an efflux pump inhibitor control or check for genetic resistance markers [23] [13].

- Assay Sensitivity: Dye leakage assays are highly sensitive but can be influenced by vesicle preparation quality. Always quantify lipid concentration using a method like the Stewart assay [23].

Nucleic Acid Targeting Mechanisms

Q3: Beyond membrane disruption, how do some antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) target bacterial nucleic acids?

A3: Research has revealed several sophisticated mechanisms for nucleic acid targeting:

- Phase Transition Modulation: A significant number of AMPs can undergo liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) with nucleic acids, forming biomolecular condensates. This compartmentalization can effectively inhibit essential processes like transcription and translation by compacting nucleic acids and sequestering them from the cellular machinery [26]. Machine learning analysis indicates nearly 62% of AMPs have a high propensity for this nucleic acid-mediated phase separation [26].

- Direct Interaction and Condensation: AMPs like Buforin-2 can bind directly to DNA and RNA, leading to nucleoid condensation without causing immediate cell lysis, which disrupts nucleic acid metabolism [26].

- Enzyme Inhibition via Chaperone Binding: Some proline-rich AMPs, such as those from bottle fly larvae, can bind to essential bacterial chaperones like DnaK. This binding inhibits proper protein folding, which is a downstream effect that can be linked to nucleic acid metabolism and enzyme function [24].

Q4: I want to investigate the phase separation of my AMP with nucleic acids. What is the experimental workflow?

A4: The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for this investigation, integrating in silico prediction with in vitro and cellular validation.

Troubleshooting Phase Separation Experiments:

- No Condensates Observed: Ensure the right buffer conditions (pH, salt concentration). Phase separation can be highly sensitive to ionic strength and the presence of crowding agents [26].

- Distinguishing from Aggregation: Liquid-like condensates should be spherical, fuse over time, and show internal dynamics. Use fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) to confirm liquid character [26].

Enzyme Inhibition Mechanisms

Q5: What are the primary modes of enzyme inhibition by antimicrobial agents, and how can I characterize them?

A5: Enzyme inhibition generally falls into two main categories, which can be distinguished through kinetic studies:

- Competitive Inhibition: The inhibitor (e.g., a natural antimicrobial compound) binds to the active site of the enzyme, directly competing with the natural substrate. The key diagnostic is that the apparent

K_mincreases, while theV_maxremains unchanged because, at high substrate concentrations, the substrate can outcompete the inhibitor [27]. - Non-Competitive Inhibition: The inhibitor binds to an allosteric site on the enzyme, not the active site. This binding alters the enzyme's conformation and reduces its catalytic efficiency. The key diagnostic is a decrease in

V_max, while theK_mtypically remains the same [27].

Q6: My enzyme inhibition assay shows poor efficacy with a purified target enzyme. Could the peptide be acting on a different target?

A6: Yes, this is a strong possibility. AMPs often have multiple, synergistic targets.

- Check for Membrane Priming: Many AMPs need to interact with the membrane before reaching intracellular enzymes. The membrane interaction can cause depolarization or pore formation, facilitating cellular entry. Use membrane depolarization assays (e.g., DiSC3(5)) in parallel [23] [25].

- Investigate Alternative Intracellular Targets: The observed inhibition might be a secondary effect. The peptide could be disrupting cellular homeostasis (e.g., by binding to chaperones like DnaK, inhibiting protein folding) or triggering stress responses that indirectly affect enzyme activity [24].

- Confirm Cellular Penetration: Use fluorescently labeled peptides and microscopy or flow cytometry to verify that the peptide is entering the cell without causing massive membrane rupture [23] [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Investigating Direct Antimicrobial Mechanisms

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Model Membrane Systems [23] | Langmuir monolayers; Liposomes (LUVs, GUVs); Solid-supported lipid bilayers | Screening peptide-lipid interactions; studying membrane disruption mechanisms (leakage, fusion) in a controlled system. |

| Fluorescent Dyes & Probes [23] | N-phenyl-1-napthylamine (NPN); DiSC3(5); SYTO 9/Propidium Iodide (PI); SYTOX Green; Calcein/Carboxyfluorescein | Assessing outer/cytoplasmic membrane integrity, membrane potential, and cell viability in bacteria and model vesicles. |

| Characterized AMPs [26] [25] | Buforin-2; P113; Os-C; LL-37; Gramicidin S; Indolicidin | Used as positive controls in mechanistic studies for membrane disruption, cellular uptake, and nucleic acid binding. |

| Computational Tools [26] | DeePhase (Machine Learning Algorithm) | Predicting the propensity of AMP sequences to undergo phase separation with nucleic acids. |

| Key Pathogen Strains [13] | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA); Carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP); E. coli; P. aeruginosa | Essential for testing efficacy against clinically relevant, resistant pathogens in vitro and in vivo. |

| Hydroxymetronidazole | 1-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-2-hydroxymethyl-5-nitroimidazole | 1-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-2-hydroxymethyl-5-nitroimidazole (Hydroxymetronidazole) is a key metabolite for antimicrobial research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| 4-Chlorosalicylic acid | 4-Chlorosalicylic acid, CAS:5106-98-9, MF:C7H5ClO3, MW:172.56 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Integrated Antimicrobial Mechanisms

The following diagram synthesizes the three direct antimicrobial mechanisms—membrane disruption, enzyme inhibition, and nucleic acid targeting—into a single, integrated view of how natural antimicrobial agents, particularly AMPs, exert their effects and overcome resistance.

Antimicrobial resistance represents a critical global health threat, with biofilm-associated infections and efflux pump-mediated drug extrusion being major contributors to treatment failure [28]. Efflux pumps are membrane proteins that confer multidrug resistance to microorganisms and are involved in multiple stages of biofilm formation [29]. Natural compounds offer a promising therapeutic strategy to overcome these resistance mechanisms through efflux pump inhibition (EPI) and biofilm disruption, potentially restoring the efficacy of conventional antimicrobials [30] [31]. This technical support center provides researchers with practical methodologies and troubleshooting guidance for investigating natural agents that target these resistance mechanisms, framed within the context of developing novel therapeutic approaches to combat drug-resistant pathogens.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Concepts

Q1: What is the relationship between efflux pumps and biofilm formation? Efflux pumps contribute to biofilm formation through several mechanisms: (i) impacting initial microbial adherence to surfaces, (ii) transporting metabolites and quorum sensing (QS) system signals, (iii) extruding harmful substances including antimicrobials, and (iv) indirectly mediating biofilm-associated gene expression [29]. The regulatory functions of efflux pumps in biofilm formation include mediating adherence, QS systems, and expression of biofilm-related genes [29].

Q2: Why are natural compounds promising for resistance modulation? Natural compounds, particularly plant-derived phytochemicals, offer several advantages: they typically cause minimal side effects, demonstrate dose flexibility, and can be administered as combination therapies to enhance antibiotic effectiveness [31]. These compounds exhibit diverse biological activities, including antimicrobial, efflux pump inhibitory, resistance modulatory, and membrane permeabilizing effects [30] [32].

Q3: What are the key stages of biofilm development? Biofilm formation occurs through five distinct stages: (1) reversible attachment of planktonic cells to surfaces, (2) irreversible attachment with phenotypic and genotypic changes, (3) maturation and early development of biofilm architecture, (4) maturation and formation of a three-dimensional structure, and (5) dispersal of cells to form new biofilms [31].

Experimental Design & Troubleshooting

Q4: Which bacterial models are appropriate for studying efflux pump inhibition? Mycobacterium smegmatis serves as an excellent model organism for anti-tubercular drug screening due to its genomic similarities and correlating antibiotic susceptibility profile to M. tuberculosis [30]. For studying Gram-negative pathogens, ESKAPEE organisms (particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii) are highly relevant due to their clinical prevalence and robust efflux systems [28].

Q5: What are common issues with false-positive EPI identification and how can they be avoided? False positives can occur due to compound toxicity or antibiotic enhancement through non-EPI mechanisms. To address this: (1) include appropriate controls (e.g., bacterial viability assays alongside accumulation studies), (2) use multiple complementary assays (e.g., ethidium bromide accumulation plus checkerboard synergy testing), and (3) validate findings with efflux pump knockout strains (e.g., M. smegmatis ΔlfrA mutant) [30] [33].

Q6: How can I differentiate between biofilm inhibition and general antibacterial effects? Utilize sub-inhibitory concentrations of test compounds in biofilm assays and compare results with planktonic growth curves. True biofilm inhibitors will significantly reduce biofilm formation at concentrations that minimally affect planktonic growth [32]. Additionally, microscopic visualization (e.g., confocal, holotomography) can confirm structural disruption without complete growth inhibition [34].

Q7: What are the key considerations for combination therapy experiments? When testing natural EPIs with conventional antibiotics: (1) determine fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) indices to quantify synergy, (2) include appropriate controls for each compound alone, (3) consider the order of administration (pre-treatment vs. co-administration), and (4) validate findings in relevant infection models (e.g., murine skin infection models) [33].

Quantitative Data on Natural Compounds with Resistance Modulation Activity

Table 1: Natural Compounds with Demonstrated Efflux Pump Inhibitory Activity

| Compound/Source | Target Organism | Efflux Pump Target | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peucedanum ostruthium (Masterwort) extracts | Mycobacterium smegmatis | LfrA efflux pump | Showed resistance modulation effects on ethidium bromide activity; interfered with LfrA efflux pump action | [30] |

| Ostruthin (from P. ostruthium) | M. smegmatis, M. fortuitum | Not specified | Attributed with major antibacterial effect; more lipophilic substrates showed greater antimicrobial effect | [30] |

| Imperatorin (from P. ostruthium) | Mycobacterium smegmatis | LfrA efflux pump | Caused potent modulatory effects by interfering with LfrA efflux pump action | [30] |

| Montelukast (FDA-approved drug) | Staphylococcus aureus | NorB efflux pump (MgrA regulator) | Showed synergy with moxifloxacin; decreased norB expression and increased pknB/rsbU expression ratio | [33] |

| Palmatine (plant compound) | P. mirabilis, E. coli, E. faecalis, B. cereus | Sortase A | Showed antimicrobial activity; belongs to Sortase A inhibitors; changed growth curve characteristics | [34] |

| Curcumin (from Curcuma longa) | Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Quorum sensing systems | Inhibited biofilm formation, motility and virulence factor production; non-toxic phytochemical | [35] |

Table 2: Natural Compounds with Biofilm Disruptive Activity

| Compound/Agent | Target Organism | Mode of Action | Effectiveness | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEcPP (plant stress metabolite) | Escherichia coli | Disrupts fimbriae production via fimE gene enhancement | Prevents initial biofilm attachment by disrupting bacterial anchoring capability | [36] |

| Curcumin | Vibrio species (V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus, V. harveyi) | Inhibits quorum sensing systems | Inhibits biofilm formation, motility and virulence factor production | [35] |

| Berberine | Multiple foodborne pathogens | Sortase A inhibition | Antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity; changes characteristics of cluster development | [34] |

| Piperine | Multiple bacterial species | Not specified | Identified as having antibacterial potential as a phyto-constituent | [31] |

| ε-Polylysine | Food spoilage bacteria | Disrupts cell membrane | Increases membrane permeability, disturbs cell membrane integrity, suppresses quorum-sensing phenotype | [35] |

| Essential oils (e.g., Origanum compactum) | Various bacteria | Membrane disruption | Increase membrane permeability, disturb cell membrane integrity, suppress quorum-sensing | [35] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Ethidium Bromide Accumulation Assay for Efflux Pump Inhibition

Principle: This assay measures the intracellular accumulation of ethidium bromide (EtBr), a substrate for many efflux pumps. EPIs will increase intracellular EtBr fluorescence by blocking its extrusion [30] [33].

Procedure:

- Grow bacterial culture to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.4-0.6)

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (3,500 × g, 10 min) and wash with PBS (pH 7.4)

- Resuspend cells to OD600 = 0.2 in PBS containing glucose (0.4% w/v)

- Add test compound at sub-inhibitory concentration and incubate for 10 min

- Add EtBr to final concentration of 1-2 μg/mL

- Immediately measure fluorescence (excitation: 530 nm, emission: 600 nm) every 30-60 sec for 30 min

- Include controls: cells alone (negative control), cells + EtBr (baseline efflux), cells + EtBr + known EPI (positive control)

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low signal: Optimize cell density and EtBr concentration; verify instrument sensitivity using CCCP (carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone), which abolishes efflux

- High background: Ensure proper washing to remove media components; include killed cell controls

- Non-linear kinetics: Maintain constant temperature; ensure adequate mixing between readings

Checkerboard Synergy Assay for Combination Therapy

Principle: This method determines the interaction between natural EPIs and conventional antibiotics by calculating the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) index [28] [33].

Procedure:

- Prepare two-fold serial dilutions of antibiotic in Mueller-Hinton broth (or appropriate medium) along rows of 96-well plate

- Prepare two-fold serial dilutions of natural EPI along columns

- Inoculate wells with standardized bacterial suspension (5 × 10^5 CFU/mL final concentration)

- Incubate at appropriate temperature for 16-20 h

- Determine MIC of each compound alone and in combination

- Calculate FIC index = (MIC antibiotic in combination/MIC antibiotic alone) + (MIC EPI in combination/MIC EPI alone)

Interpretation: FIC index ≤0.5: synergy; >0.5-4: additive/indifference; >4: antagonism

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Edge effects: Use interior wells for critical dilutions; include medium controls

- Poor growth: Verify inoculum size using colony counting; check medium freshness

- High EPI MIC: Use higher maximum concentrations for poorly soluble compounds with DMSO (<1% final)

Biofilm Inhibition and Disruption Assays

Crystal Violet Biofilm Quantification:

- Grow biofilms in 96-well plates for desired duration (typically 24-48 h)

- Carefully remove planktonic cells and wash gently with PBS

- Fix biofilms with methanol or ethanol for 15 min

- Stain with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 min

- Wash extensively to remove unbound dye

- Solubilize bound dye with 30% acetic acid or ethanol-acetone mixture (80:20)

- Measure absorbance at 570-600 nm

Troubleshooting Tips:

- High variability: Use consistent washing protocol; avoid disrupting biofilm

- Background staining: Include sterility controls; optimize washing steps

- Non-specific binding: Use surface-binding controls (e.g., BSA)

Confocal Microscopy for Biofilm Architecture:

- Grow biofilms on appropriate surfaces (e.g., glass coverslips, catheter pieces)

- Treat with test compounds at sub-MIC concentrations

- Stain with LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit or specific matrix component stains

- Image using confocal laser scanning microscopy

- Analyze using image analysis software (e.g., COMSTAT, ImageJ) for biomass, thickness, and viability parameters

Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms of Action

Diagram Title: Natural Compound Mechanisms Against Bacterial Resistance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Resistance Modulation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Organisms | Mycobacterium smegmatis mc² 155 (wild type & ΔlfrA mutant), ESKAPEE pathogens (S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, E. coli) | Efflux pump studies, biofilm formation assays | Select strains with relevant, characterized efflux systems; verify mutation stability |

| Reference EPIs | PAβN (Phe-Arg β-naphthylamide), Thioridazine, NMP (1-(1-naphthylmethyl)-piperazine), CCCP | Positive controls for efflux inhibition assays | Solubility limitations; potential toxicity at high concentrations |

| Biofilm Stains | Crystal violet, LIVE/DEAD BacLight, SYTO dyes, Congo red, Calcofluor white | Biofilm quantification and visualization | Specificity for live/dead cells vs. matrix components; compatibility with imaging systems |

| Natural Compound Libraries | Coumarins (ostruthin, imperatorin), Alkaloids (berberine, palmatine), Curcuminoids, Flavonoids (quercetin) | Screening for novel resistance modulators | Solubility (often require DMSO); stability in aqueous solution; purity verification |

| QS Signal Molecules | AHLs (C4-HSL, 3-oxo-C12-HSL), AIPs, AI-2 | Quorum sensing inhibition studies | Species-specific; stability in media; appropriate storage conditions |

| Gene Expression Tools | qPCR primers for norA, norB, mgrA, adeB, lfraA; reporter strains | Mechanistic studies of EPI action | Validate reference genes; optimize extraction for biofilm cells |

| 2,5-Dihydroxybenzaldehyde | 2,5-Dihydroxybenzaldehyde, CAS:1194-98-5, MF:C7H6O3, MW:138.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Hesperetin 7-O-glucoside | Hesperetin 7-O-glucoside, CAS:31712-49-9, MF:C22H24O11, MW:464.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Methodologies

Transcriptomic Analysis of Biofilm Cells

For investigating global gene expression changes in response to natural resistance modulators:

- Grow biofilms under controlled conditions with sub-MIC of test compound

- Harvest biofilm cells using gentle scraping or enzymatic treatment

- Extract RNA using optimized protocols for biofilm cells (include DNase treatment)

- Perform RNA sequencing or targeted qPCR arrays for efflux pump and biofilm-associated genes

- Validate findings with mutant strains

Key Targets: Efflux pump genes (norA, norB, adeB, lfraA), quorum sensing regulators (lasI, lasR, luxS), biofilm matrix genes (pel, psl, alg), and adhesion factors [30] [33] [29].

Holotomography for Biofilm Analysis

Digital holotomography provides label-free, quantitative analysis of biofilm structural changes:

- Grow biofilms on appropriate imaging chambers

- Treat with natural compounds at sub-MIC concentrations

- Image using holotomography microscope at appropriate intervals

- Analyze median refractive index (RI) values, volume of structures, and dry mass

- Compare treated vs. untreated biofilms for structural parameters [34]

This approach enables real-time monitoring of biofilm disruption without introducing staining artifacts.

From Discovery to Delivery: Advanced Extraction, Screening, and Formulation Technologies

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support resource addresses common experimental and ethical challenges in ethnopharmacology research aimed at discovering natural antimicrobial agents to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary ethical consideration when using Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) in bioprospecting? The foremost consideration is obtaining Prior Informed Consent (PIC) and establishing Mutually Agreed Terms (MAT) with indigenous communities. This ensures the community is fully aware of the research scope and agrees to how their knowledge and biological resources will be used. It protects their rights and ensures fair sharing of any benefits arising from commercialization [37].

FAQ 2: Our antimicrobial assays against WHO priority pathogens show inconsistent results. What could be the cause? Inconsistencies can often be traced to the extraction solvent. The bioactive compounds in plants (alkaloids, flavonoids, etc.) have varying solubilities. Ensure you are using a range of solvents (e.g., ethanol, methanol, aqueous, ethyl acetate) in your initial screens to comprehensively capture the antimicrobial potential of your samples [8].

FAQ 3: How can we ensure our bioprospecting activities are not considered biopiracy? To avoid biopiracy, adhere to international frameworks like the Nagoya Protocol, which provides a legal framework for access and benefit-sharing. Furthermore, go beyond the minimum legal requirements by engaging indigenous communities as research partners, respecting their cultural heritage, and ensuring they receive fair and equitable benefits from the research outcomes [38] [37].

FAQ 4: Why is it important to document the traditional methods of plant preparation? Traditional preparation methods (e.g., decoction, infusion, fermentation) can critically influence the bioavailability and efficacy of active compounds. The therapeutic effect may result from synergistic interactions between multiple compounds in the crude extract, which could be lost during isolation of a single compound [39] [40]. Documenting and, where relevant, mimicking these methods can be key to replicating the traditional remedy's efficacy.

FAQ 5: Which plant compounds are most frequently associated with antimicrobial activity against resistant bacteria? Systematic reviews indicate that several classes of plant-derived secondary metabolites show significant promise. The table below summarizes the key compound classes and their actions [8] [41].

Table 1: Key Plant-Derived Compound Classes with Antimicrobial Potential

| Compound Class | Example Bioactivities | Common Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Disrupt bacterial cell membranes; intercalate with DNA [8]. | Bark, roots, leaves |

| Flavonoids | Antioxidant; inhibit bacterial enzymes like gyrase [8]. | Leaves, flowers, fruits |

| Phenols & Tannins | Bind to proteins and disrupt microbial cell walls [8]. | Bark, fruits, leaves |

| Terpenoids | Disrupt membrane integrity [8]. | Resins, essential oils |

| Saponins | Have membrane-permeabilizing properties [8]. | Roots, leaves |

Troubleshooting Experimental Protocols

This section provides guided workflows for diagnosing and resolving common experimental problems.

Scenario 1: Failure to Detect Antimicrobial Activity in a Plant Extract with Documented Traditional Use

1. Identify the Problem A plant sample, used traditionally for treating infections, shows no zone of inhibition in a standard disc diffusion assay against a target WHO priority pathogen like Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

2. List All Possible Explanations

- Bioactive Composition: The active compounds are not extracted by the solvent used.

- Concentration: The concentration of the active compound in the extract is below the detection threshold.

- Assay Condition: The assay conditions (e.g., growth medium) are not optimal for the compound's activity.

- Synergy: The activity is synergistic and requires the full crude extract, not a single compound.

3. Collect Data & Eliminate Explanations

- Vary Extraction Protocols: Re-extract the plant material using solvents of different polarities (e.g., hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, methanol, water) [8].

- Concentrate the Extract: Use rotary evaporation to create a more concentrated extract for testing.

- Modify the Bioassay: Try a different assay method, such as a broth microdilution Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) assay, which can be more sensitive than disc diffusion.

- Test for Synergy: Use a checkerboard assay to test if the crude extract potentiates the effect of a conventional antibiotic at a sub-lethal dose [41].

4. Experimental Protocol: Broth Microdilution for MIC Determination

- Materials: 96-well microtiter plate, Mueller-Hinton broth, bacterial suspension (adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard), plant extract, positive control antibiotic (e.g., ciprofloxacin), DMSO solvent control.

- Procedure:

- Dispense broth into all wells.

- Add the plant extract to the first well and perform a two-fold serial dilution across the plate.

- Add the standardized bacterial inoculum to all test wells.

- Include growth control (bacteria only) and sterility control (broth only) wells.

- Cover the plate and incubate at 37°C for 18-24 hours.

- The MIC is the lowest concentration of extract that prevents visible growth.

5. Identify the Cause If activity is detected in the MIC assay with a methanolic extract but not the aqueous one, the cause is likely the extraction solvent. The active compounds are medium-polarity and not efficiently extracted by water.

Scenario 2: Inconsistent Replication of Traditional Remedy's Efficacy

1. Identify the Problem A laboratory-produced version of a traditional herbal preparation is less effective than the healer's original preparation in an animal model of infection.

2. List All Possible Explanations

- Preparation Method: Key steps in the traditional preparation (e.g., specific heating time, fermentation, order of ingredient addition) were not precisely replicated.

- Plant Source & Quality: Differences in the plant's chemotype due to soil, season of harvest, or post-harvest storage.

- Holistic Context: The traditional healing process involves non-pharmacological elements (e.g., ritual, healer-patient relationship) that contribute to the overall outcome [40].

3. Collect Data & Eliminate Explanations

- Ethnographic Validation: Re-engage with the knowledge holders to review and verify every detail of the preparation protocol.