Evaluating Chemical Similarity Methods for Natural Products: From Foundations to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Chemical similarity calculation is a cornerstone of cheminformatics, crucial for ligand-based virtual screening and drug discovery.

Evaluating Chemical Similarity Methods for Natural Products: From Foundations to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

Chemical similarity calculation is a cornerstone of cheminformatics, crucial for ligand-based virtual screening and drug discovery. However, the unique structural complexity of natural products—characterized by large molecular weights, high stereochemical complexity, and distinct scaffolds—poses distinct challenges for conventional similarity methods. This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of chemical similarity methods specifically for natural product research. We explore foundational concepts, advanced methodological approaches including circular fingerprints and retrobiosynthetic analysis, and strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. By synthesizing evidence from controlled synthetic data and real-world case studies, we offer comparative insights and validation frameworks to guide researchers in selecting and applying the most effective similarity methods for exploring natural product chemical space, ultimately accelerating the identification of novel bioactive compounds.

Why Natural Products Are a Cheminformatic Challenge: Unique Properties and the Need for Specialized Similarity Methods

The Critical Role of Chemical Similarity in Modern Drug Discovery Pipelines

The concept that structurally similar molecules tend to exhibit similar biological activities is a foundational principle in cheminformatics that has transformed modern drug discovery [1] [2]. This chemical similarity principle provides the computational basis for predicting protein targets, assessing toxicity, and identifying lead compounds across vast chemical spaces. For natural products (NPs)—prominent sources of pharmaceutically important agents—similarity-based methods are particularly valuable due to their structurally complex scaffolds and optimized biological activities refined through evolution [1] [3]. Despite their promise, accurately predicting targets for NPs remains challenging due to their structural complexity and limited bioactivity data [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of current chemical similarity methodologies, their performance metrics, and experimental protocols, focusing specifically on applications in natural product research.

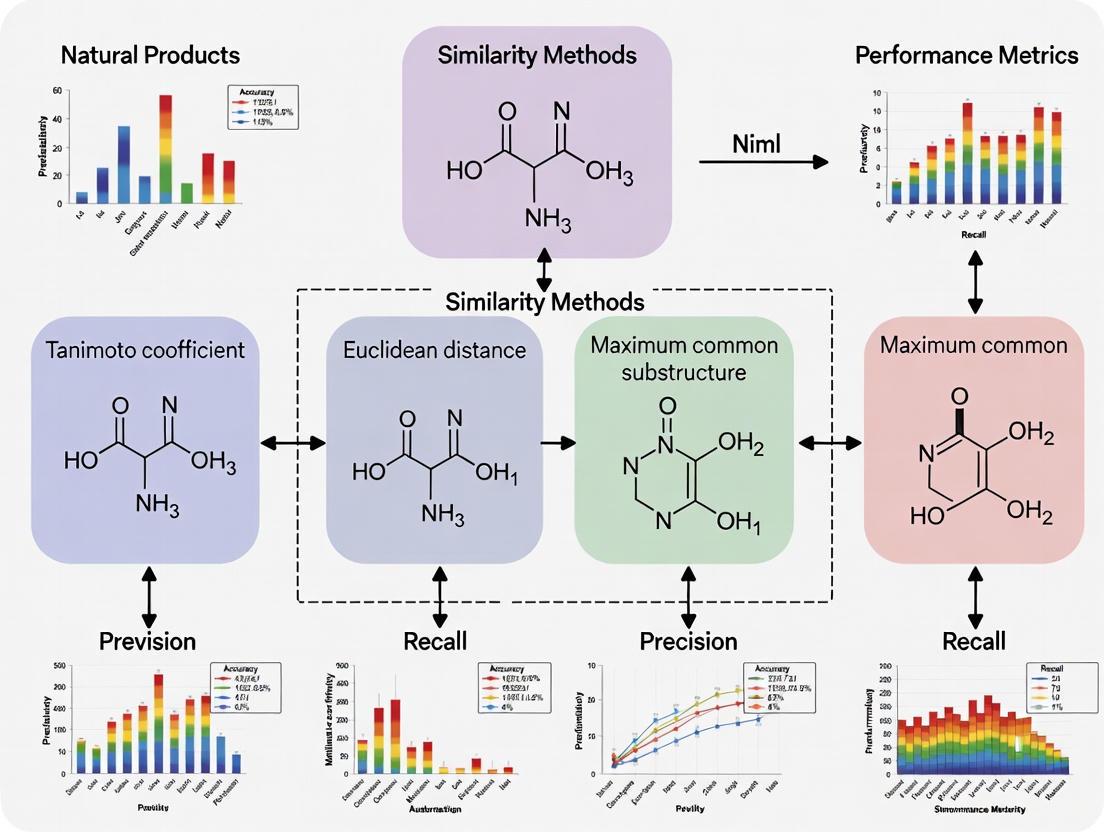

Comparative Analysis of Chemical Similarity Methodologies

Fundamental Approaches and Definitions

Chemical similarity methods are broadly categorized by their molecular representation and alignment strategies. Two-dimensional (2D) similarity methods utilize structural fingerprints encoding molecular substructures, while three-dimensional (3D) similarity approaches incorporate molecular shape and pharmacophore features [2]. The Tanimoto coefficient remains the standard metric for quantifying 2D similarity, calculated as the number of common fingerprint bits divided by the total number of unique bits in both molecules [2].

Performance Comparison of Representative Tools

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Chemical Similarity Tools for Target Prediction

| Tool Name | Similarity Approach | Molecular Representation | Reported Success Rate | Specialization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTAPred | 2D similarity-based | Fingerprint-based | High performance for NPs [1] | Natural products |

| CSNAP3D | Combined 2D/3D network | Shape & pharmacophore | >95% for 206 known drugs [2] | Scaffold hopping |

| SEA | 2D similarity ensemble | Molecular fingerprints | Applied to NPs successfully [1] | Multiple target identification |

| TargetHunter | 2D similarity | Fingerprint-based | Validated for salvinorin A [1] | Natural products |

| D3CARP | 2D & 3D flexible alignment | Multiple fingerprints & 3D shape | Enhanced accuracy for complex NPs [1] | Natural products |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of 3D Similarity Approaches for Scaffold Hopping

| 3D Similarity Metric | Basis of Comparison | Average AUC | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| ShapeAlign (ComboScore) | Shape + pharmacophore | 0.60 [2] | Diverse scaffold enrichment |

| ROCS (TanimotoCombo) | Shape + color force | 0.59 [2] | Target-specific enrichment |

| Shape-only metrics | Molecular volume | 0.52 [2] | High-shape similarity |

| Pharmacophore-only | Chemical feature alignment | 0.55 [2] | Feature-matched compounds |

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

CTAPred Protocol for Natural Product Target Prediction

Objective: To predict protein targets for natural product query compounds using a optimized similarity-based approach [1].

Workflow:

- Reference Dataset Construction: Compile a Compound-Target Activity (CTA) dataset from sources including ChEMBL, COCONUT, NPASS, and CMAUP, focusing on targets relevant to natural products [1].

- Fingerprint Generation: Convert all reference and query compounds to standardized molecular fingerprints.

- Similarity Calculation: Compute Tanimoto coefficients between query compounds and all reference compounds in the CTA dataset.

- Hit Identification: Rank reference compounds by similarity scores and select the top N most similar compounds (optimal performance typically with top 3-5 hits) [1].

- Target Prediction: Assign targets associated with the top N reference compounds as potential targets for the query compound.

- Validation: Experimental validation through in vitro binding or functional assays is essential to confirm predictions [1].

Figure 1: CTAPred workflow for natural product target prediction

CSNAP3D Protocol for Scaffold Hopping Identification

Objective: To identify scaffold hopping compounds and predict their targets using combined 2D/3D similarity network analysis [2].

Workflow:

- 3D Conformer Generation: Generate biologically active conformations for all query and reference compounds using programs like MOE.

- Shape Alignment: Perform initial shape alignment between query and reference compounds using Shape-it software.

- Pharmacophore Mapping: Generate consensus pharmacophore features using Align-it program on the shape-aligned conformations.

- Similarity Scoring: Calculate combo scores combining shape Tanimoto index and number of matching pharmacophore points.

- Network Analysis: Construct chemical similarity networks and classify compounds into chemotypes sharing common scaffolds.

- Target Prediction: Apply network-based scoring (S-score) to identify common drug targets in the first-order network neighborhood of query compounds.

- Experimental Validation: Confirm predictions using in vitro assays (e.g., microtubule polymerization assays for antimitotic compounds) [2].

Figure 2: CSNAP3D workflow for scaffold hopping identification

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Similarity Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL, NPASS, CMAUP [1] | Provide annotated compound-target relationships for reference datasets |

| Natural Product Libraries | COCONUT, NANPDB, StreptomeDB [1] | Source of natural product structures and bioactivity data |

| Fingerprinting Tools | RDKit, Circular fingerprints (FP2, FP4) [1] | Generate molecular representations for similarity calculation |

| 3D Similarity Software | ROCS, Shape-it, Align-it [2] | Perform shape-based and pharmacophore-based molecular alignments |

| Similarity Search Servers | TargetHunter, SEA, SwissTargetPrediction [1] | Web-based platforms for target prediction |

| Experimental Validation Assays | Microtubule polymerization assays [2] | Functional validation for target predictions (e.g., antimitotic compounds) |

Chemical similarity methodologies have evolved significantly beyond simple 2D fingerprint approaches to incorporate 3D shape, pharmacophore matching, and network-based analytics [1] [2]. For natural products research, hybrid approaches that combine multiple similarity metrics show particular promise in addressing the unique challenges posed by structurally complex NPs [1] [3]. The emerging concept of the "informacophore"—minimal chemical structures combined with computed molecular descriptors and machine-learned representations—represents the next evolution in similarity-based discovery, potentially enabling more systematic and bias-resistant identification of bioactive natural products [4]. As chemical libraries expand to billions of make-on-demand compounds and natural product databases grow, advanced similarity methods that efficiently navigate this chemical space will become increasingly critical for accelerating natural product-based drug discovery [5] [4].

Defining the Natural Product Chemical Space: Key Structural and Physicochemical Properties

The chemical space of natural products (NPs) represents a vast reservoir of molecular diversity honed by billions of years of evolution. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the structural and physicochemical properties that define NPs against synthetic compounds (SCs), framing this discussion within the performance evaluation of chemical similarity methods. For researchers in drug discovery, understanding these distinctions is crucial for selecting appropriate computational tools to navigate the NP chemical space, identify new drug leads, and overcome the limitations of conventional screening libraries when addressing challenging biological targets.

Natural products have been a cornerstone of drug discovery, with approximately 60% of medicines approved in the last three decades deriving from NPs or their semi-synthetic derivatives [1]. Their historical success is attributed to evolutionary selection for bioactivity, resulting in complex structures that interact with diverse biological macromolecules [6]. The term "chemical space" refers to the multi-dimensional descriptor space encompassing all possible small organic molecules, and NPs occupy a distinct and privileged region within this space [7] [8].

However, the shift towards high-throughput screening (HTS) and combinatorial chemistry in the pharmaceutical industry highlighted a critical issue: the structural diversity of synthetic compound libraries is often insufficient to probe the full range of biological targets, particularly those deemed "challenging" or "undruggable" [7]. This guide objectively compares the defining properties of NPs and SCs, providing the foundational knowledge required to effectively evaluate and apply chemical similarity methods in natural product research.

Comparative Analysis of Key Properties: NPs vs. SCs

A comprehensive, time-dependent chemoinformatic analysis reveals fundamental and evolving differences between NPs and SCs. The data below summarizes key comparisons, drawing from large-scale studies of NP and SC databases [6].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Physicochemical Properties

| Property | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) | Analysis Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Generally larger; increasing over time [6] | Smaller; constrained by synthesis and drug-like rules [6] | NP size offers larger binding surfaces for challenging targets like protein-protein interfaces [7]. |

| Ring Systems | More rings, especially large, fused non-aromatic assemblies; increasing complexity [6] | Fewer rings; higher proportion of aromatic rings (e.g., benzene) [6] | NP scaffolds provide complex, diverse structural templates often absent in synthetic libraries [6] [8]. |

| Complexity & Stereochemistry | Higher structural complexity, more stereocenters [6] [7] | Lower complexity, fewer stereocenters [6] | Enhances target selectivity but poses challenges for chemical synthesis and library design [7]. |

| Hydrophobicity (AlogP) | Trend towards increased hydrophobicity in newer NPs [6] | Hydrophobicity varies within a constrained, "drug-like" range [6] | Influences ADMET properties; NPs may access different bioavailability pathways (e.g., active transport) [7]. |

| Oxygen & Nitrogen Content | Higher oxygen atom count [6] | Higher nitrogen atom count [6] | Reflects different biosynthetic versus synthetic pathways and impacts hydrogen bonding potential. |

| Structural Diversity | High scaffold diversity, occupying broad but distinct chemical space [6] [8] | Broader absolute diversity but clustered in "drug-like" regions [6] | NPs explore a different and relevant biological region of chemical space, inspiring pseudo-NP design [6]. |

Table 2: Distribution and Drug Relevance in Chemical Space

| Aspect | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Congregation | 62.7% of NP leads for approved drugs cluster in 62 drug-productive scaffolds/branches [8] | N/A | Analysis of 442 NP leads of drugs (NPLDs) against 137,836 non-redundant NPs [8]. |

| Fingerprint Clustering | 82.5% of approved NPLDs clustered in 60 drug-productive clusters [8] | N/A | Hierarchical clustering with 881-bit PubChem fingerprints and Tanimoto coefficient [8]. |

| Biological Relevance | High, evolved through natural selection [6] | Declining over time, despite broader synthetic pathways [6] | Time-dependent analysis of 186,210 NPs and 186,210 SCs grouped by chronology [6]. |

| Privileged Target Binding | Preferentially bind to 45 privileged target-site classes [8] | Focused on a narrow set of target classes (e.g., GPCRs, kinases) [7] | Clustered distribution of NPLDs is linked to privileged target-site binding [8]. |

Methodologies for Mapping the Natural Product Chemical Space

The quantitative comparison of NPs and SCs relies on well-established chemoinformatic protocols. The following workflows and tools are essential for defining and navigating the NP chemical space.

Standardized Experimental Protocols for Chemoinformatic Analysis

Protocol 1: Time-Dependent Property Analysis This methodology was used to generate the trend data in [6].

- Data Collection: Curate large datasets of NPs and SCs from databases like the Dictionary of Natural Products and various synthetic compound databases.

- Chronological Ordering: Sort molecules in early-to-late order using a consistent identifier, such as the CAS Registry Number.

- Grouping: Divide the sorted molecules into sequential groups (e.g., 37 groups of 5,000 molecules each) to create a time series.

- Descriptor Calculation: For each group, compute a suite of physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, AlogP, number of rings, heavy atoms).

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate mean and distribution for each property per group and analyze trends over time for both NPs and SCs.

Protocol 2: Molecular Scaffold and Fingerprint Tree Generation This protocol is used to map the clustering of NPs and NPLDs, as in [8].

- Dataset Curation: Collect a non-redundant set of NP structures and known NPLDs.

- Scaffold Tree Generation:

- Tool: Scaffold Hunter v2.3.0.

- Method: Process molecules with ring structures using the software's default rule set to generate hierarchical scaffold trees, which represent the core structures of molecules.

- Fingerprint-based Clustering:

- Fingerprint: Compute 2D molecular fingerprints (e.g., 881-bit PubChem substructure fingerprints) using a tool like PaDEL.

- Similarity Metric: Calculate pairwise Tanimoto coefficients (Tc).

- Clustering Algorithm: Use hierarchical clustering with complete linkage (e.g., via Matlab Statistics Toolbox).

- Visualization: Generate tree graphs with tools like EMBL's iTOL, using Tanimoto distance (Td = 1 - Tc).

Visualization of Analytical Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a comprehensive chemoinformatic analysis of natural products, integrating the key protocols described above.

Diagram 1: Workflow for comprehensive chemoinformatic analysis of natural products, integrating time-dependent property analysis and chemical space mapping.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Databases for NP Chemical Space Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in NP Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| PaDEL [8] | Software | Computes molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures. | Generating 881-bit PubChem fingerprints for hierarchical clustering of NPs. |

| Scaffold Hunter [8] | Software | Generates hierarchical scaffold trees from compound datasets. | Visualizing and analyzing the scaffold diversity and distribution of NPLDs. |

| COCONUT [1] [9] | Database | Open-access repository of elucidated and predicted natural products. | Sourcing NP structures for comparative chemical space analysis against FDA-approved drugs. |

| ChEMBL [1] | Database | Large-scale public database of drug-like bioactive compounds. | Sourcing synthetic compounds and bioactivity data for benchmarking against NPs. |

| CTAPred [1] | Software Tool | Open-source, command-line tool for predicting protein targets for NPs. | Leveraging similarity-based searches on a tailored NP-reference dataset for target prediction. |

| LANaPDB [9] | Database | Unified Latin American Natural Product Database. | Exploring region-specific biodiversity and its unique contribution to the NP chemical space. |

Implications for Chemical Similarity Methods in NP Research

The distinct structural and property landscapes of NPs directly impact the performance and application of chemical similarity methods.

Addressing the Similarity Paradox for NPs: The principle that "similar compounds behave similarly" can break down with complex NPs, leading to "activity cliffs" [10]. Advanced methods like Read-Across Structure-Activity Relationship (RASAR) incorporate similarity and error-based descriptors to improve predictive performance for NPs, offering enhanced external predictivity compared to conventional QSAR models [11] [10].

Target Prediction Challenges: Standard similarity-based target prediction tools (e.g., SwissTargetPrediction) are often trained on drug-like molecules and may perform poorly for NPs with complex scaffolds and high stereochemical density [1]. Specialized tools like CTAPred are being developed to address this gap by creating reference datasets focused on protein targets relevant to NPs, thereby improving prediction accuracy [1].

Inspiring Library Design: The analysis confirms that NPs explore regions of chemical space underrepresented in synthetic libraries [6] [7]. This validates strategies like designing pseudo-natural products by combining NP fragments to create novel compounds that inherit biological relevance while exploring new biological space [6]. The following diagram illustrates how the unique properties of NPs influence the discovery and design of new bioactive molecules.

Diagram 2: The influence of key natural product properties on drug discovery strategies and tool development.

The chemical space of natural products is uniquely defined by structural complexity, diversity, and a evolutionary bias towards biological relevance. Quantitative comparisons reveal that NPs are consistently larger, more stereochemically complex, and contain more oxygen atoms and complex ring systems than their synthetic counterparts. Furthermore, NP leads for drugs are not randomly distributed but cluster in specific, drug-productive regions of the chemical space, often associated with privileged target sites.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these distinctions are not merely academic. They underscore the necessity of selecting and developing specialized chemical similarity methods, such as RASAR and CTAPred, that are calibrated to the unique features of the NP chemical space. Effectively navigating this space requires moving beyond methods optimized for synthetic, "drug-like" libraries and leveraging the distinct properties of NPs to discover leads for the most challenging biological targets. The continued systematic mapping of the NP chemical space, aided by the methodologies and tools outlined in this guide, is essential for unlocking its full potential in drug discovery and development.

The systematic comparison of natural products (NPs) and synthetic compounds (SCs) reveals fundamental differences in their structural complexity, chemical space, and physicochemical properties. These distinctions present significant challenges and opportunities for chemical similarity search methods in drug discovery. This guide provides a quantitative analysis of NPs and SCs, details experimental protocols for evaluating similarity search performance, and offers practical resources for researchers. The findings indicate that while NPs exhibit greater structural diversity and biological relevance, their unique characteristics necessitate specialized computational approaches for effective similarity-based virtual screening.

Natural products and synthetic compounds originate from fundamentally different processes—biological evolution versus laboratory synthesis—resulting in distinct chemical landscapes. NPs are substances produced by living organisms, including plants, animals, and microorganisms, and have evolved to interact with biological systems [12] [13]. In contrast, SCs are created through chemical synthesis, often designed with considerations for synthetic accessibility and drug-like properties [13]. This divergence in origin has profound implications for chemical similarity search methodologies, which are crucial for virtual screening in drug discovery.

The historical influence of NPs on drug development is substantial, with approximately 68% of approved small-molecule drugs between 1981 and 2019 being directly or indirectly derived from NPs [13]. However, the structural evolution of these two compound classes has diverged over time. Recent chemoinformatic analyses reveal that NPs have become larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic, while SCs have evolved under the constraints of synthetic feasibility and drug-like rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five [13]. This expanding structural gap challenges traditional similarity search algorithms, which often perform better within more uniform chemical spaces.

Structural and Physicochemical Comparison

Comprehensive analysis of molecular descriptors reveals consistent differences between NPs and SCs that directly impact similarity search performance. These differences span molecular size, ring systems, and other structural features that determine how compounds occupy chemical space.

Molecular Size and Complexity

Table 1: Physicochemical Properties of Natural Products vs. Synthetic Compounds

| Property | Natural Products | Synthetic Compounds | Implications for Similarity Search |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Higher (increasing over time) [13] | Lower, constrained by drug-like rules [13] | NP-NP similarities may be underestimated by size-insensitive metrics |

| Number of Heavy Atoms | Higher [13] | Lower [13] | Atom-count dependent fingerprints may overweight NP features |

| Number of Rings | Higher, increasing over time [13] | Lower [13] | Scaffold-based methods must accommodate complex ring systems |

| Aromatic Rings | Fewer [13] | More prevalent [13] | Aromaticity-based fingerprints favor SC space |

| Oxygen Atoms | More abundant [13] | Fewer [13] | Oxygen-containing functional groups differentiate NP space |

| Nitrogen Atoms | Fewer [13] | More abundant [13] | Heteroatom-sensitive metrics may distinguish NP/SC classes |

| Stereocenters | More prevalent [13] | Fewer [13] | Stereochemistry-aware fingerprints needed for NP searches |

| Structural Diversity | Higher [13] | Lower [13] | Diverse NP space requires broader similarity thresholds |

Ring Systems and Scaffold Diversity

Ring systems represent fundamental structural frameworks that significantly influence molecular shape and biological activity. NPs contain more rings but fewer ring assemblies compared to SCs, indicating the presence of larger fused ring systems (such as bridged rings and spiral rings) in NPs [13]. Recent NPs show increasing glycosylation ratios and greater numbers of sugar rings, adding to their complexity [13].

In contrast, SCs are characterized by a higher prevalence of aromatic rings, particularly five- and six-membered rings which are synthetically accessible and energetically stable [13]. A notable trend in modern SCs is the sharp increase in four-membered rings, which are incorporated to improve pharmacokinetic properties [13]. These differences in ring system architecture necessitate similarity methods that can handle diverse ring types and connectivity patterns.

Figure 1: Structural Divergence Between Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds. NP structures evolve toward complexity while SCs follow synthetic accessibility.

Experimental Protocols for Similarity Search Evaluation

Rigorous assessment of similarity search methods requires standardized protocols and benchmarking datasets. The following methodologies enable quantitative comparison of algorithm performance across NP and SC chemical spaces.

Compound Collection Preparation

Reference Standard Development: Curate a benchmark dataset from established sources including the Dictionary of Natural Products (for NPs) and multiple synthetic compound databases (for SCs) [13]. Ensure accurate annotation of discovery dates to enable time-series analysis [13].

Chemical Standardization: Apply consistent standardization protocols including salt removal, neutralization of charges, and tautomer normalization. For NPs, retain stereochemical information which is crucial for biological activity [13].

Dataset Stratification: Divide compounds into temporal groups (e.g., 5,000 molecules per group) based on registration dates to analyze historical trends [13]. Include both known bioactive compounds and decoy molecules to evaluate virtual screening performance.

Similarity Metric Calculation

Descriptor Computation: Generate multiple molecular representations including:

- Extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFP) of various diameters

- Path-based fingerprints

- Physicochemical property descriptors (molecular weight, logP, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, etc.)

- Scaffold-based descriptors (Murcko scaffolds, ring systems, side chains)

Similarity Assessment: Calculate pairwise similarities using Tanimoto coefficient, Cosine similarity, and Euclidean distance. For scaffold-based comparisons, use maximum common substructure (MCS) approaches.

Performance Validation: Employ retrospective virtual screening using known active-inactive pairs from public databases (ChEMBL, BindingDB). Measure performance via enrichment factors, area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC), and precision-recall curves.

Chemical Space Visualization and Analysis

Dimensionality Reduction: Apply principal component analysis (PCA), t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) to visualize the distribution of NPs and SCs in chemical space [13].

Scaffold Diversity Analysis: Apply Murcko scaffold decomposition to quantify framework diversity using Shannon entropy metrics [13]. Compare the diversity of NP and SC collections using scaffold trees and network representations.

Temporal Evolution Tracking: Analyze how NP and SC chemical spaces have diverged or converged over time by comparing property distributions across chronological groupings [13].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Similarity Method Evaluation. Comprehensive assessment requires multiple complementary approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Resources for Natural Product Similarity Search Research

| Resource | Function | Application in NP Research |

|---|---|---|

| Dictionary of Natural Products | Comprehensive NP database [13] | Reference data for benchmarking and training |

| PheKnowLator (NP-KG) | Knowledge graph for NPs and interactions [14] | Mechanism-aware similarity searching |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit | Molecular descriptor calculation and fingerprint generation |

| OpenBabel | Chemical format conversion | Data standardization and preprocessing |

| NaPDI Database | Expert-curated NP-drug interactions [14] | Bioactivity-based similarity validation |

| COCONUT Database | Natural product collection [13] | Diverse NP structures for method testing |

| ChEMBL | Bioactivity database | Active/inactive pairs for performance testing |

| KNIME | Workflow platform | Pipeline creation for large-scale similarity screening |

Implications for Similarity Search Method Development

The structural differences between NPs and SCs have significant consequences for chemical similarity search applications in virtual screening and compound prioritization.

Challenges in NP-Focused Similarity Searching

High Structural Complexity: NPs contain more stereocenters, complex ring systems, and diverse functional groups compared to SCs [13]. This complexity challenges traditional similarity metrics that may not adequately capture three-dimensional molecular features or rare structural motifs.

Sparse Chemical Space: NPs occupy regions of chemical space that are less densely populated by SCs [13]. This sparsity reduces the effectiveness of similarity methods that rely on dense reference spaces for accurate neighborhood identification.

Biological Relevance Bias: NPs have evolved to interact with biological targets, resulting in inherently higher hit rates in biological screening [13]. However, this biological relevance may not be fully captured by structural similarity metrics alone, necessitating hybrid approaches that incorporate bioactivity data.

Methodological Recommendations

Descriptor Selection: Implement combination approaches using both structural fingerprints and physicochemical property descriptors. For NP-focused studies, include 3D shape-based descriptors and stereochemistry-aware representations.

Similarity Metric Adaptation: Develop class-specific similarity thresholds rather than applying uniform cutoffs across NP and SC spaces. Consider asymmetric similarity measures that account for the hierarchical relationship between complex NPs and simpler SCs.

Temporal Considerations: Account for the evolving nature of chemical spaces in method validation. Include time-split validation sets where training and testing compounds are separated by discovery date to simulate real-world prospective screening scenarios.

Knowledge Graph Integration: Incorporate biological context through knowledge graph embedding approaches, which have shown promise for predicting natural product-drug interactions and may enhance similarity searching by incorporating functional relationships [14].

Natural products and synthetic compounds inhabit distinct and evolving regions of chemical space, characterized by fundamental differences in structural complexity, ring systems, and physicochemical properties. These differences directly impact the performance of chemical similarity search methods, with traditional approaches often struggling with the structural diversity and complexity of NPs. Effective navigation of NP chemical space requires specialized methodologies that account for stereochemistry, complex ring systems, and temporal evolution patterns. The experimental protocols and resources outlined in this guide provide a foundation for rigorous evaluation of similarity search methods in natural products research, enabling more effective virtual screening and compound prioritization in drug discovery campaigns.

The LEMONS (Library for the Enumeration of MOdular Natural Structures) algorithm represents a specialized bioinformatics tool designed to address the unique challenges of quantifying molecular similarity for natural products. Unlike conventional synthetic compounds, natural products possess large, structurally complex scaffolds that distinguish their physical and chemical properties, creating a pressing need for evaluation methods tailored to this specific chemical space [15] [16]. The core function of LEMONS is the enumeration of hypothetical modular natural product structures, which provides a controlled framework for the comparative analysis of chemical similarity methods [15]. This algorithm fills a critical methodological gap, as prior to its development, no comprehensive analysis of molecular similarity calculation performance specific to natural products had been reported, despite their immense importance as sources of pharmaceutical and industrial agents [15] [16].

Natural products exhibit distinct characteristics—including greater three-dimensional complexity, more stereocenters, higher fractions of sp³ carbons, and more heteroatoms—that differentiate them from synthetic compounds found in standard screening libraries [15]. The biological activities of these molecules have been extensively optimized by natural selection, making the accurate quantification of their similarity a particularly valuable task for drug discovery and genome mining [15] [16]. LEMONS addresses this need by generating libraries of hypothetical structures that mirror the biosynthetic pathways of modular natural products such as nonribosomal peptides, polyketides, and their hybrids, subsequently modifying these structures through monomer substitutions or alterations to tailoring reactions, and then evaluating whether chemical similarity methods can correctly identify the original structure from the modified one [15]. This approach provides a rigorous, controlled mechanism for benchmarking similarity search performance within this specialized chemical domain.

Experimental Framework and Methodologies

Core Architecture of the LEMONS Algorithm

The LEMONS algorithm operates through a structured workflow that leverages biosynthetic principles to generate and evaluate hypothetical natural product structures. Implemented as a Java software package, LEMONS enumerates hypothetical natural product structures based on user-defined biosynthetic parameters including monomer composition, tailoring reactions, macrocyclization patterns, and starter units [15]. This generative approach allows researchers to create synthetic datasets that accurately reflect the structural diversity and complexity of naturally occurring modular architectures, providing a foundation for controlled comparative studies.

The evaluation mechanism of LEMONS follows a systematic procedure. For each original structure generated by the algorithm, LEMONS creates modified versions through monomer substitutions or by adding, removing, or changing the site of tailoring reactions [15]. These modified structures are then compared against the entire library of original structures using various chemical similarity methods. A critical aspect of the evaluation is that the "ground truth" is known—the algorithm tracks which modified structure originated from which original structure—enabling precise measurement of similarity method performance [15]. A "correct match" is scored when the modified structure demonstrates greater chemical similarity to its original progenitor than to any other structure in the library. This process repeats across multiple structures and modifications, with the final performance metric being the proportion of correct matches achieved by each similarity method [15].

Key Experimental Protocols

The foundational experiment validating the LEMONS approach involved generating libraries of short polymers of proteinogenic amino acids [15]. In this controlled proof-of-concept study, researchers created a library of 100 oligomers with lengths ranging from 4-15 amino acids. For each structure, a single amino acid was substituted to create a modified version, and the Tanimoto coefficient between the modified structure and each original structure was calculated using multiple chemical similarity methods. This process was repeated systematically, with each of the 100 original structures undergoing modification, and the entire experiment was replicated 100 times to ensure statistical robustness [15]. Through this design, approximately 10,000 original structures, 10,000 modified structures, and 100 million comparisons were generated for each similarity method, establishing a substantial dataset for meaningful performance evaluation [15].

For more complex natural product simulations, LEMONS was used to generate libraries of hypothetical nonribosomal peptides, polyketides, and hybrid natural products [15]. The experimental framework comprehensively investigated how various biosynthetic parameters affect similarity search performance, including the impacts of monomer composition, starter units, macrocyclization, and diverse tailoring reactions such as glycosylation, halogenation, and N-methylation [15]. In each experiment, the core methodology remained consistent: generate original structures, create modified versions through controlled structural alterations, compute similarity metrics between modified and original structures, and calculate the percentage of correct matches for each chemical fingerprinting method. This standardized protocol enables direct comparison of performance across different similarity methods and natural product classes.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for LEMONS Experiments

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| LEMONS Algorithm | Software Library | Enumerates hypothetical modular natural product structures and facilitates their modification and comparison [15] |

| Circular Fingerprints (ECFP/FCFP) | Chemical Descriptor | Encodes molecular structures as fixed-length bit vectors based on circular atom environments for similarity comparison [15] |

| Tanimoto Coefficient | Similarity Metric | Quantifies the similarity between two molecular fingerprints by calculating the ratio of shared bits to total bits [15] |

| Substructure Key Fingerprints (MACCS, PubChem) | Chemical Descriptor | Represents molecules as bit strings where each bit indicates the presence or absence of specific predefined chemical substructures [15] |

| GRAPE/GARLIC | Retrobiosynthetic Tool | Executes in silico retrobiosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides and polyketides and performs comparative analysis of biosynthetic information [15] |

| Topological Fingerprints (CDK) | Chemical Descriptor | Generates molecular representations based on structural topology and connectivity patterns [15] |

Comparative Performance Analysis of Chemical Similarity Methods

Performance Across Natural Product Classes

The LEMONS framework enabled the first comprehensive comparative analysis of chemical similarity methods specifically for modular natural products. The evaluation encompassed 17 distinct chemical fingerprint algorithms alongside the GRAPE/GARLIC retrobiosynthetic approach, providing a broad assessment of available methodologies [15]. Performance was measured across different classes of natural products, including nonribosomal peptides (NRPs), polyketides (PKs), and hybrid structures, with results demonstrating significant variation in effectiveness depending on both the similarity method and the natural product class under investigation.

A key finding from these controlled experiments was that circular fingerprints (particularly ECFP and FCFP variants) generally delivered robust performance across diverse natural product classes [15]. These fingerprints, which decompose molecular structures into circular atom neighborhoods, demonstrated consistent effectiveness in correctly identifying relationships between original and modified natural product structures. Additionally, the GRAPE/GARLIC retrobiosynthetic approach demonstrated exceptional performance when rule-based retrobiosynthesis could be applied, in some cases outperforming conventional two-dimensional fingerprints [15]. This suggests that methods leveraging biosynthetic logic may offer particular advantages for the targeted exploration of natural product chemical space, especially for classes like nonribosomal peptides and polyketides with well-characterized biosynthetic pathways.

Impact of Structural Features on Similarity Search

The LEMONS framework systematically investigated how specific structural features of natural products influence the performance of similarity methods. Parameters such as molecular size (number of monomers), macrocyclization, and various tailoring reactions (including glycosylation, halogenation, and heterocyclization) were evaluated for their impact on similarity search accuracy [15]. These investigations revealed that certain structural modifications present greater challenges for some similarity methods than others, providing valuable insights for method selection based on the specific characteristics of the natural products under study.

The experiments demonstrated that the performance of some similarity methods exhibits a ligand size dependency, with effectiveness varying based on the number of monomers in the natural product structure [15]. Additionally, the introduction of starter units (common in many modular natural product pathways) and macrocyclization patterns significantly influenced similarity search outcomes [15]. These findings highlight the importance of considering structural complexity when selecting similarity methods for natural product research. The comprehensive analysis using LEMONS provides guidance for method selection based on the specific structural features most relevant to a researcher's natural products of interest.

Table 2: Performance of Chemical Similarity Methods on Modular Natural Products

| Similarity Method | Type | Key Strengths | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP4/ECFP6 | Circular Fingerprint | Generally robust performance across natural product classes [15] | Effective for diverse natural product structures including NRPs, PKs, and hybrids |

| FCFP4/FCFP6 | Circular Fingerprint | Feature-based circular patterns | Comparable performance to ECFP variants in natural product similarity assessment |

| GRAPE/GARLIC | Retrobiosynthetic Alignment | Superior performance when biosynthetic rules apply [15] | Outperforms conventional 2D fingerprints for applicable natural product classes |

| MACCS | Substructure Keys | Predefined chemical substructures | Reasonable performance in controlled experiments with modular natural products [15] |

| PubChem Fingerprint | Substructure Keys | Comprehensive substructure patterns | Effective for natural product similarity search in LEMONS evaluation [15] |

| CDK Extended | Topological Fingerprint | Structural topology-based | Competitive performance with other fingerprint types for natural products [15] |

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

In the foundational experiments with proteinogenic peptide libraries, most chemical similarity algorithms demonstrated reasonable performance in identifying the correct original structure after single amino acid substitutions [15]. This initial validation established a baseline for method performance before progressing to more complex natural product structures. The experimental results indicated that while multiple approaches could achieve success in this simplified scenario, certain methods began to distinguish themselves as more effective for the specific task of natural product similarity assessment.

When applied to the more structurally complex libraries of hypothetical modular natural products, the LEMONS evaluation revealed clearer performance differentiations between methods. The retrobiosynthetic GRAPE/GARLIC approach demonstrated particularly strong performance when applicable, suggesting its value for targeted exploration of natural product chemical space and microbial genome mining [15]. The extensive comparative analysis across multiple natural product classes and structural modifications provides researchers with evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate similarity methods based on their specific natural product research goals, whether focused on nonribosomal peptides, polyketides, hybrid structures, or specifically tailored variants.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The LEMONS algorithm implements a structured workflow for the generation and evaluation of hypothetical natural product structures. The following diagram visualizes this systematic process:

The LEMONS algorithm represents a significant methodological advancement for the systematic evaluation of chemical similarity methods within the unique chemical space of modular natural products. By enabling the controlled generation of hypothetical structures and their modified variants, LEMONS provides a rigorous framework for benchmarking similarity search performance that accounts for the complex structural features characteristic of natural products. The comprehensive comparative analysis conducted using this framework demonstrates that while circular fingerprints generally deliver robust performance across diverse natural product classes, retrobiosynthetic approaches like GRAPE/GARLIC can outperform conventional two-dimensional fingerprints when applicable biosynthetic rules are available [15].

These findings have important implications for natural product research and drug discovery. The ability to reliably quantify molecular similarity for natural products facilitates more effective virtual screening, genome mining, and chemical space exploration [15] [16]. The LEMONS approach and the insights derived from its application represent valuable tools for researchers seeking to leverage the structural diversity and optimized biological activities of natural products for pharmaceutical development. As the field continues to evolve, the standardized evaluation framework provided by LEMONS offers a foundation for assessing new similarity methods developed specifically for the challenges of natural product research.

A Practical Guide to Chemical Similarity Methods: From Fingerprints to Retrobiosynthesis and Machine Learning

Natural products (NPs) offer unexplored molecular frameworks for the development of chemical leads and innovative drugs, with approximately 50% of FDA-approved medications (1981-2006) being NPs or their synthetic derivatives [17]. However, the structural complexity of natural products compared with synthetic drug-like molecules often limits the scaffold hopping potential of natural-product-inspired molecular design [18]. Molecular similarity methods, particularly structural fingerprints, provide computational solutions for identifying structurally distinct compounds that share similar bioactivity, a process crucial for leveraging NPs in drug discovery.

Among these methods, Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) have emerged as one of the most popular similarity search tools in drug discovery [19]. This guide provides a performance-focused comparison of ECFP against alternative molecular similarity methods specifically within the challenging context of natural products research, summarizing experimental data and methodologies to inform researcher selection of appropriate computational tools.

Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP)

ECFPs are circular topological fingerprints designed for molecular characterization, similarity searching, and structure-activity modeling [19]. The ECFP generation algorithm represents molecules through a set of circular atom neighborhoods, systematically capturing molecular features around each non-hydrogen atom through an iterative process [19] [20].

Diagram 1: ECFP Generation Workflow illustrating the algorithmic process from molecular input to final fingerprint.

Key ECFP properties include [19]:

- Circular atom neighborhoods that capture radial molecular environments

- Rapid computation without predefined substructural keys

- Flexible diameter parameter controlling the radial extent (ECFP_4 = diameter 4)

- Molecule-directed feature generation using hashing procedures

The most common ECFP variants are distinguished by their diameter: ECFP4 (diameter 4) is typically sufficient for similarity searching and clustering, while ECFP6 (diameter 6) provides greater structural detail often beneficial for activity learning methods [19].

Alternative Molecular Similarity Approaches

While ECFPs represent a leading circular fingerprint method, several alternative approaches offer different strategies for molecular similarity assessment, particularly relevant for natural products:

WHALES (Weighted Holistic Atom Localization and Entity Shape) descriptors provide a holistic molecular representation specifically designed to address limitations of reductionist representations for natural products [18]. WHALES simultaneously encode information on geometric interatomic distances, molecular shape, and atomic partial charge distributions, capturing pharmacophore and shape patterns that facilitate scaffold hopping from natural products to synthetic mimetics [18].

Path-based fingerprints such as Atom Pair (AP) and Topological Torsion (TT) fingerprints represent molecules based on linear paths through the molecular graph, contrasting with ECFP's circular approach [21]. Performance studies indicate these may offer advantages in specific similarity contexts, particularly for ranking very close analogues [21].

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Benchmarking

Virtual Screening and Similarity Searching Performance

Comprehensive benchmarking studies provide quantitative performance comparisons across multiple fingerprint methods. A landmark study evaluating 28 different fingerprints found that ECFP4 and ECFP6 were among the best-performing fingerprints when ranking diverse structures by similarity, as was the topological torsion fingerprint [21].

Table 1: Fingerprint Performance in Structural Similarity Benchmarking

| Fingerprint | Type | Close Analogue Ranking | Diverse Structure Ranking | Virtual Screening Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP4 | Circular | Good | Excellent | Among best performers |

| ECFP6 | Circular | Good | Excellent | Top tier performance |

| Topological Torsion | Path-based | Good | Excellent | Comparable to ECFP4 |

| Atom Pair | Path-based | Best | Good | Good |

| WHALES | Holistic | Not tested | Excellent for NPs | 35% success in prospective NP study |

The same study revealed an important implementation consideration: ECFP performance significantly improved when bit-vector length was increased from 1,024 to 16,384, reducing bit collisions and information loss [21]. For close analogue ranking, the atom pair fingerprint actually outperformed ECFP4, suggesting different fingerprints may be optimal for different similarity tasks [21].

Natural Product Scaffold Hopping Performance

In a prospective application focused specifically on natural product scaffold hopping, WHALES descriptors demonstrated exceptional capability using four phytocannabinoids as queries to search for novel synthetic modulators of human cannabinoid receptors [18]. Of the synthetic compounds selected by this method, 35% were experimentally confirmed as active—a notable success rate for prospective virtual screening [18]. These cannabinoid receptor modulators were structurally less complex than their respective natural product templates, demonstrating effective scaffold hopping from complex natural products to synthetically accessible compounds [18].

Table 2: Natural Product Scaffold Hopping Performance

| Method | Query NPs | Target | Success Rate | Novel Scaffolds Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHALES | 4 phytocannabinoids | Cannabinoid receptors (CB1, CB2) | 35% (7/20 compounds) | 5 out of 7 active scaffolds novel vs. ChEMBL |

| ECFP4 | Benchmark datasets from ChEMBL | Multiple targets | Varies by target | Good performance on standard benchmarks |

The superior performance of WHALES in this NP-focused application highlights how holistic molecular representations that simultaneously capture partial charge, atom distributions, and molecular shape can effectively address the unique challenges of natural product complexity [18]. This contrasts with conventional single-feature descriptors that may struggle with the structural differences between natural and synthetic compounds [18].

Methodologies: Experimental Protocols and Implementation

ECFP Implementation and Configuration

For researchers implementing ECFP-based similarity searching, the following methodological details are essential:

Generation Process Protocol [19] [20]:

- Initial atom identifier assignment: Assign integer identifiers capturing atomic number, connection count, hydrogen count, formal charge, and ring atom status

- Iterative updating: Perform multiple iterations to combine initial atom identifiers with neighbor identifiers up to specified diameter

- Duplicate removal: Eliminate structurally equivalent identifiers while preserving unique features

Critical Configuration Parameters [19]:

- Diameter: Controls radial extent (ECFP_4 default for similarity searching)

- Length: Bit-vector length (1,024-16,384 bits, longer reduces collisions)

- Counts: Whether to store occurrence counts (ECFC) or presence-only (ECFP)

Diagram 2: Method Selection Framework for choosing molecular similarity approaches based on research goals and query type.

WHALES Descriptor Calculation Protocol

For holistic molecular similarity approaches optimized for natural products, the WHALES descriptor calculation involves [18]:

- Atom-centered covariance matrix calculation: Compute weighted covariance matrices centered on each atom using partial charges as weights

- Atom-centered Mahalanobis distance calculation: Transform interatomic distances using the inverse covariance matrices

- Atomic indices calculation: Compute remoteness, isolation degree, and their ratio for each atom

- Descriptor generation: Apply binning procedure to atomic indices to obtain fixed-length representation (33 descriptors total)

This methodology enables simultaneous capture of pharmacophore features, shape patterns, and charge distributions that are particularly relevant for natural product functional mimicry [18].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Molecular Similarity Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics | Fingerprint generation & similarity calculations | General purpose, includes ECFP implementation |

| Chemaxon GenerateMD | Commercial cheminformatics | ECFP generation with configurable parameters | Production virtual screening |

| ChEMBL database | Bioactivity database | Source of benchmark datasets & NP activities | Method validation & testing |

| WHALES descriptors | Custom algorithm | Holistic similarity for NP scaffold hopping | NP-inspired drug discovery |

| CRC-32 hash function | Algorithmic component | Creates integer identifiers in ECFP generation | Fingerprint implementation |

Based on the experimental data and performance benchmarks, ECFP fingerprints remain excellent general-purpose tools for molecular similarity tasks, showing consistently strong performance across diverse benchmarking studies [21]. However, for the specific challenge of natural product scaffold hopping, holistic approaches like WHALES descriptors demonstrate superior performance by simultaneously capturing pharmacophore, shape, and charge information often critical for NP bioactivity [18].

Research recommendations include:

- For general similarity searching and virtual screening, ECFP4 and ECFP6 provide top-tier performance

- For close analogue searching, Atom Pair fingerprints may outperform ECFP

- For natural product scaffold hopping to synthetic mimetics, WHALES descriptors offer proven success

- Always use extended bit-vector lengths (≥16,384) for ECFP implementations to minimize information loss

The optimal choice of molecular similarity method ultimately depends on the specific research context—whether the goal is close analogue finding, diverse scaffold hopping, or natural product mimicry—with each method offering distinct advantages for particular applications in drug discovery.

Calculating chemical similarity is a fundamental task in cheminformatics, with critical applications throughout the drug discovery pipeline, particularly in natural products research [3]. The unique structural complexity of natural products, characterized by large and structurally complex scaffolds optimized by natural selection, presents distinct challenges for molecular similarity comparison [3]. Unlike simpler synthetic compounds, natural products possess physical and chemical properties that demand specialized computational approaches for meaningful similarity assessment. This evaluation is particularly important for modular natural products—complex molecules assembled through biosynthetic pathways involving multiple enzymatic steps—where traditional similarity methods often fail to capture essential biosynthetic logic.

Retrobiosynthetic alignment represents an advanced methodology that addresses these limitations by incorporating biosynthetic reasoning into similarity assessment. Where conventional two-dimensional fingerprints primarily compare structural features, retrobiosynthetic methods analyze the hypothetical enzymatic assembly processes that nature uses to construct these molecules [3]. This approach enables researchers to identify not just structural analogs but also compounds that share common biosynthetic origins, potentially uncovering deeper relationships within natural product chemical space. For researchers exploring microbial natural products, which represent a prominent source of pharmaceutically important agents, these advanced alignment techniques offer powerful opportunities for genome mining, analog design, and biosynthetic pathway prediction [22] [3].

Comparative Analysis of Chemical Similarity Methods

The performance evaluation of chemical similarity methods requires careful consideration of multiple parameters, particularly when applied to modular natural products. Traditional fingerprint-based approaches, including various two-dimensional structural fingerprints, calculate similarity based on shared molecular substructures or properties. In contrast, retrobiosynthetic alignment employs rule-based retrobiosynthesis to decompose molecules according to plausible biosynthetic logic, then assesses similarity based on these biosynthetic building blocks and assembly patterns [3].

To quantitatively compare these approaches, researchers have utilized controlled synthetic data generated by algorithms such as LEMONS (an algorithm for the enumeration of hypothetical modular natural product structures) [3]. This enables systematic evaluation of how different biosynthetic parameters—including module diversity, stereochemical complexity, and structural rearrangements—impact similarity search performance across methodologies. The key performance differentiators between these approaches are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Chemical Similarity Methods for Modular Natural Products

| Performance Metric | Traditional 2D Fingerprints | Retrobiosynthetic Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| Biosynthetic Relevance | Low - based solely on structural similarity | High - incorporates biosynthetic logic and pathway information |

| Scaffold Hopping Ability | Limited to structurally similar compounds | Enhanced - can identify compounds with different structures but shared biosynthetic origins |

| Stereochemical Sensitivity | Variable - often poorly handles stereochemistry | High - explicitly accounts for stereochemical features through enzymatic rules |

| Computational Complexity | Low to moderate | High - requires retrobiosynthetic analysis |

| Data Requirements | Requires only structural information | Depends on comprehensive enzymatic reaction databases |

| Performance on Modular NPs | Suboptimal - may miss biosynthetic relationships | Superior - specifically designed for modular architectures |

Experimental Evidence and Validation Studies

Comparative analyses using controlled synthetic data have demonstrated that retrobiosynthetic alignment significantly outperforms conventional two-dimensional fingerprints for natural product similarity assessment when rule-based retrobiosynthesis can be properly applied [3]. This performance advantage is particularly pronounced for modular natural products, where the biosynthetic logic provides critical information that is not captured by structural fingerprints alone. The ability of retrobiosynthetic methods to identify biosynthetically related compounds, even when they share limited structural similarity, represents a substantial advancement for natural product discovery and classification.

The fundamental strength of retrobiosynthetic alignment lies in its biological relevance. By mirroring nature's biosynthetic strategies, this approach creates similarity metrics that more accurately reflect actual biological relationships between natural products [3]. This capability proves particularly valuable for genome mining applications, where researchers can use retrobiosynthetic analysis to connect biosynthetic gene clusters to their likely molecular products, significantly accelerating the discovery process for novel natural products with desired structural features or biological activities [22].

Retrobiosynthetic Alignment Methodologies

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

Retrobiosynthetic alignment operates on the principle that natural products are assembled through defined biosynthetic pathways, and that similarity in assembly logic often correlates with functional similarity. The methodology involves deconstructing target molecules into their plausible biosynthetic precursors using enzymatic reaction rules, then comparing these deconstruction pathways across different molecules [3]. This approach effectively reverses the biosynthetic process to uncover fundamental building relationships that may be obscured at the structural level.

The workflow typically begins with the application of generalized enzymatic reaction rules to target natural products, generating potential biosynthetic precursors through logical retrosynthetic steps [23]. These precursors are then further deconstructed iteratively until reaching simple building blocks. The resulting biosynthetic "tree" provides a framework for comparing molecules based on their shared biosynthetic features rather than just their final structural attributes. This method proves particularly powerful for analyzing modular natural products like polyketides and nonribosomal peptides, where the assembly logic follows clearly defined biosynthetic rules [3].

Implementation Tools and Databases

Several computational tools have been developed to facilitate retrobiosynthetic alignment. The RDEnzyme tool represents one such advancement, capable of extracting and applying stereochemically consistent enzymatic reaction templates [23]. These templates describe subgraph patterns that capture changes in connectivity between product molecules and their corresponding reactants, enabling consistent handling of stereochemistry—a critical aspect of natural product biosynthesis that is often poorly addressed by conventional methods.

Effective implementation of retrobiosynthetic alignment depends heavily on comprehensive enzymatic reaction databases. Resources such as RHEA, which contains approximately 5,500 enzymatic transformations, and UniProt provide the foundational knowledge base for rule application [23]. Molecular similarity serves as an effective metric to propose retrosynthetic disconnections based on analogy to precedent enzymatic reactions within these databases. In validation studies, using RHEA as a knowledge base, the recorded reactants for a product were among the top 10 proposed suggestions in 71% of approximately 700 test reactions, demonstrating the practical utility of this approach [23].

Figure 1: Retrobiosynthetic Alignment Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process of analyzing natural products through biosynthetic deconstruction and comparison.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Controlled Evaluation Framework

Robust evaluation of chemical similarity methods requires carefully designed experimental protocols that eliminate biases and enable direct comparison. The LEMONS algorithm provides such a framework by generating hypothetical modular natural product structures with controlled biosynthetic parameters [3]. This approach allows researchers to systematically investigate the impact of diverse biosynthetic features—including module selection, stereochemical configuration, and structural rearrangements—on similarity search performance across different methodologies.

In a typical evaluation protocol, researchers first generate a library of hypothetical natural products using predefined biosynthetic rules and parameters [3]. This synthetic ground truth ensures that all biosynthetic relationships between molecules are known in advance, enabling objective assessment of each method's ability to recover these known relationships. Query molecules are then selected from the library, and each similarity method is tasked with identifying the most similar compounds from the remaining library members. Performance is quantified using standard information retrieval metrics, including precision, recall, and mean average precision, with particular emphasis on each method's ability to identify biosynthetically related compounds across varying levels of structural similarity.

Benchmarking Procedures

Comprehensive benchmarking involves testing each similarity method across multiple dimensions of natural product structural space. Key evaluation parameters include:

- Structural Diversity: Assessing performance across natural products with varying degrees of structural complexity and scaffold diversity

- Biosynthetic Logic: Evaluating how well each method captures relationships between compounds sharing biosynthetic pathways but differing in final structure

- Stereochemical Sensitivity: Measuring the impact of stereochemical variations on similarity scores

- Scalability: Testing computational efficiency with increasing database sizes and structural complexity

For retrobiosynthetic alignment specifically, validation typically involves retrospective analysis of known natural product families with established biosynthetic pathways [3]. The method is assessed on its ability to correctly group compounds from the same biosynthetic family and distinguish them from unrelated structures, even when superficial structural similarities might suggest different relationships.

Effective natural products research requires access to comprehensive, well-curated databases that provide essential structural, biosynthetic, and taxonomic information. The current database landscape includes both broad natural product repositories and specialized resources focused specifically on microbial metabolites, which are particularly relevant for retrobiosynthetic studies [22].

Table 2: Essential Database Resources for Natural Products Research

| Database | Content Focus | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Products Atlas | Microbial natural products | 25,523 compounds; links to MIBiG and GNPS; filter by taxonomy | Free [22] |

| NPASS | Natural products (multiple taxa) | 35,032 compounds; ~9,000 microbial; biological activity data | Free [22] |

| StreptomeDB | Streptomyces metabolites | 7,125 compounds; bioactivity and spectral data | Free [22] |

| MIBiG | Biosynthetic gene clusters | Standardized BGC annotations; links to natural products | Free [22] |

| RHEA | Enzymatic reactions | ~5,500 enzymatic transformations; reaction templates | Free [23] |

| Dictionary of Natural Products | Comprehensive NP collection | >30,000 compounds; rich metadata; broad literature coverage | Commercial [22] |

Computational Tools and Algorithms

Beyond databases, several specialized computational tools have been developed specifically for natural products research:

- antiSMASH: Identifies biosynthetic gene clusters from genomic sequence data; essential for connecting genetic potential to chemical output [22]

- RDEnzyme: Extracts and applies stereochemically consistent enzymatic reaction templates for retrobiosynthetic analysis [23]

- LEMONS: Enumerates hypothetical modular natural product structures for method evaluation and exploration of natural product chemical space [3]

- NaPDoS/eSNaPD: Assesses biosynthetic diversity of microbial strains for prioritization and discovery [22]

These tools collectively enable researchers to move from genomic data to chemical structures and potential bioactivities, facilitating the targeted discovery of novel natural products with desired properties.

Figure 2: Natural Product Discovery Workflow Integration. This diagram shows how retrobiosynthetic alignment integrates with other bioinformatics tools in a comprehensive discovery pipeline.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Genome Mining and Natural Product Discovery

Retrobiosynthetic alignment significantly enhances genome mining efforts by providing a direct connection between biosynthetic gene cluster analysis and potential chemical outputs. By understanding the biosynthetic logic underlying natural product assembly, researchers can more effectively predict the structural features of compounds encoded by uncharacterized gene clusters [22] [3]. This capability proves particularly valuable for prioritizing clusters for experimental investigation, focusing resources on those most likely to produce novel scaffolds or desired bioactivities.

The application of retrobiosynthetic methods enables what might be termed "biosynthetically informed" similarity searching. Where traditional approaches might overlook relationships between structurally dissimilar compounds that share biosynthetic origins, retrobiosynthetic alignment explicitly seeks these connections [3]. This approach has demonstrated particular value for exploring modular natural products like polyketides and nonribosomal peptides, where the combinatorial assembly logic creates families of compounds with varying structural features but conserved biosynthetic themes.

Enzymatic Synthesis Planning

Beyond discovery applications, retrobiosynthetic alignment informs enzymatic synthesis planning for natural product analogs. By identifying the enzymatic transformations required for natural product assembly, researchers can design synthetic pathways that leverage nature's biosynthetic strategies [23]. This approach facilitates the production of natural product analogs through pathway engineering, enabling systematic exploration of structure-activity relationships while maintaining the biosynthetic integrity of the core scaffold.

Tools like RDEnzyme demonstrate how molecular similarity can effectively propose retrosynthetic disconnections based on analogy to precedent enzymatic reactions in databases like RHEA [23]. When combined with statistical models that evaluate enzyme promiscuity and evolutionary potential, these approaches enable comprehensive planning of enzymatic synthesis routes for both natural products and commodity chemicals, offering more sustainable alternatives to traditional synthetic approaches [23].

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

Technical Limitations and Development Needs

Despite their considerable promise, retrobiosynthetic alignment methods face several significant challenges that must be addressed to maximize their utility. Currently, these approaches depend heavily on the completeness and accuracy of enzymatic reaction databases, which remain limited for many biosynthetic transformations [23]. Expanding these knowledge bases, particularly for underrepresented reaction types and non-canonical transformations, represents a critical priority for method improvement.

Additional challenges include the computational complexity of retrobiosynthetic analysis, which currently limits scalability for ultra-large screening applications, and the difficulty of handling post-biosynthetic modifications that significantly alter natural product structures [3]. Future development efforts should focus on optimizing algorithms for efficiency, improving handling of stereochemical complexity, and developing integrated workflows that combine retrobiosynthetic alignment with complementary similarity methods to leverage the strengths of each approach.

Integration with Emerging Technologies

The ongoing digital revolution in natural products research presents significant opportunities for advancing retrobiosynthetic methods [22]. Integration with machine learning approaches, particularly deep learning models trained on both structural and biosynthetic data, could enhance prediction accuracy while reducing dependence on explicitly defined reaction rules. Similarly, incorporating retrobiosynthetic alignment into increasingly sophisticated computer-aided synthesis planning platforms would bridge the gap between natural product discovery and sustainable production [23] [24].

As the field moves toward increasingly data-driven approaches, adherence to FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles in database development and tool implementation will be essential for maximizing collaborative potential [22]. This is particularly important for ensuring global access to these powerful methodologies, reducing barriers for researchers in developing nations where subscription-based commercial tools may be prohibitively expensive. Through continued development and thoughtful implementation, retrobiosynthetic alignment promises to remain at the forefront of computational methods for exploring and exploiting nature's chemical diversity.

Evolutionary Chemical Binding Similarity (ECBS) represents a paradigm shift in ligand-based virtual screening by moving beyond simple structural comparisons to incorporate evolutionarily conserved target-binding properties. This machine learning approach addresses a critical limitation of traditional chemical similarity methods, which often fail to detect meaningful biological relationships when overall structural similarity is low but key binding features are conserved. By leveraging classification similarity-learning on chemical pairs that bind homologous targets, ECBS encodes functional activity patterns that transcend superficial structural resemblance. This guide provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of ECBS against conventional fingerprint-based methods, examining experimental protocols, quantitative results across multiple drug targets, and practical implementation frameworks for natural products research.

Traditional chemical similarity searching operates on the similar property principle, which posits that structurally similar molecules likely share similar biological activities. These methods typically use molecular fingerprints—bit-string representations encoding structural features—combined with similarity coefficients like Tanimoto to quantify resemblance. However, this approach often fails when critical local molecular features for target binding are obscured by global structural comparisons.

The ECBS framework introduces a transformative approach by defining similarity through the probability that compounds bind to identical or evolutionarily related targets. This method incorporates evolutionary relationships between protein targets, recognizing that homologous proteins often share conserved binding sites, thus transferring functional relationships to their binding compounds. By focusing on these evolutionarily conserved binding features, ECBS can identify functionally similar compounds that traditional methods might overlook due to low overall structural similarity.

ECBS Methodology and Experimental Protocols

Core ECBS Framework

The ECBS method employs classification similarity-learning to distinguish between evolutionarily related chemical pairs (ERCPs) and unrelated pairs. The foundational process involves several critical steps:

- Data Collection and Integration: Chemical structures and target-binding information are compiled from databases like DrugBank and BindingDB, with binding affinity thresholds applied to ensure high-confidence interactions.

- Evolutionary Annotation: Target genes are annotated using multiple protein databases to establish evolutionary relationships at motif, domain, family, and superfamily levels.

- Feature Vector Generation: Chemical structures are converted to concatenated binary fingerprints, with feature vectors for chemical pairs created through element-wise summation.

- Model Training: Machine learning models are trained to classify ERCPs using these feature vectors, with outputs representing chemical similarity scores that prioritize selection of compounds with evolutionarily conserved binding relationships.

caption: A simplified workflow of the ECBS methodology showing the transition from individual compounds to paired analysis.

Variants of ECBS models include Target-Specific ECBS (TS-ECBS) focused on particular targets and ensemble ECBS (ensECBS) that integrates multiple models. The framework's flexibility allows incorporation of different levels of evolutionary information, from direct target identity to broader superfamily relationships [25].

Iterative ECBS Optimization

Recent advancements have introduced iterative optimization protocols that enhance ECBS performance through experimental feedback loops. This approach addresses the challenge of identifying novel chemical scaffolds with high prediction uncertainty:

- Initial Screening: A baseline ECBS model screens compound libraries to identify potential hits.