Beyond Single-Model Limits: How Data Fusion Boosts Predictive Accuracy in Biomedicine

This article explores the paradigm shift from single-technique predictive modeling to advanced data fusion strategies, with a focus on applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Beyond Single-Model Limits: How Data Fusion Boosts Predictive Accuracy in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm shift from single-technique predictive modeling to advanced data fusion strategies, with a focus on applications in biomedical research and drug development. It provides a foundational understanding of core fusion methods—early, late, and intermediate fusion—and delves into their practical implementation for integrating diverse data types like genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and clinical data. The content addresses critical challenges such as data heterogeneity and overfitting, offering optimization strategies and theoretical frameworks for method selection. Through rigorous comparative analysis and validation techniques, the article demonstrates how data fusion consistently enhances predictive accuracy, robustness, and generalizability, ultimately paving the way for more reliable tools in precision oncology and therapeutic development.

The Data Fusion Imperative: Moving Beyond Single-Source Predictions

Data fusion, also known as information fusion, is the process of integrating multiple data sources to produce more consistent, accurate, and useful information than that provided by any individual data source [1]. In artificial intelligence (AI), this involves consolidating diverse data types and formats to develop more comprehensive and robust models, leading to enhanced insights and more reliable outcomes [1].

This guide objectively compares the predictive performance of data fusion strategies against single-technique approaches, providing experimental data to underscore the critical trade-offs. The analysis is framed for researchers and professionals who require evidence-based methodologies for improving predictive accuracy in complex domains like drug development.

A Brief History of Data Fusion

The concept of data fusion originated in military operations, where it was initially employed to process information from multiple sources for strategic decision-making and intelligence analysis [1]. This field has since transcended its military origins, evolving in tandem with technological advancements in data acquisition and processing to become a cornerstone of modern AI and data science [1].

Core Data Fusion Methods: A Technical Comparison

Multisource and multimodal data fusion plays a pivotal role in large-scale AI applications. The choice of fusion strategy significantly impacts computational cost and model performance [2]. The three mainstream fusion methods are:

- Early Fusion (Data-Level Fusion): Involves the simple concatenation of original features from different modalities as the input to a single predictive model [2].

- Intermediate Fusion (Feature-Level Fusion): Learns representative features from the original data of each modality first, then fuses these features for predictive classification [2].

- Late Fusion (Decision-Level Fusion): Trains separate models on different data modalities and subsequently fuses the decisions or predictions from these individual models [2].

The workflow and logical relationships between these methods are summarized in the diagram below.

Comparative Performance and Selection Paradigm

Theoretical analysis reveals that no single fusion method is universally superior; the optimal choice depends on data characteristics. Research shows that under a generalized linear model framework, early fusion and late fusion can be mathematically equivalent under specific conditions [2]. However, early fusion can fail when nonlinear relationships exist between features and labels [2].

A critical finding is the existence of a sample size threshold where performance dominance reverses. An approximate equation evaluating the accuracy of early and late fusion as a function of sample size, feature quantity, and modality number enables the creation of a selection paradigm to choose the most appropriate method before task execution, saving computational resources [2].

Experimental Evidence: Data Fusion vs. Single-Source Models

Case Study 1: Genomic and Phenotypic Selection in Plant Breeding

Experimental Protocol: A novel data fusion framework, GPS (Genomic and Phenotypic Selection), was tested for predicting complex traits in crops [3]. The study integrated genomic and phenotypic data through three fusion strategies (data fusion, feature fusion, and result fusion) and applied them to a suite of models, including statistical approaches (GBLUP, BayesB), machine learning models (Lasso, RF, SVM, XGBoost, LightGBM), and deep learning (DNNGP) [3]. The models were rigorously validated on large datasets from four crop species: maize, soybean, rice, and wheat [3].

Performance Comparison:

| Fusion Strategy | Top Model | Accuracy Improvement vs. Best Genomic Model | Accuracy Improvement vs. Best Phenotypic Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Fusion | Lasso_D | +53.4% | +18.7% |

| Feature Fusion | - | Lower than Data Fusion | Lower than Data Fusion |

| Result Fusion | - | Lower than Data Fusion | Lower than Data Fusion |

The Lasso_D model demonstrated exceptional robustness, maintaining high predictive accuracy with sample sizes as small as 200 and showing resilience to variations in genetic marker density [3].

Case Study 2: Sea Surface Nitrate Estimation

Experimental Protocol: This study aimed to enhance the accuracy and spatial resolution of global sea surface nitrate (SSN) retrievals [4]. Researchers developed improved regression and machine learning models that fused satellite-derived data (e.g., sea surface temperature) instead of relying solely on traditional in-situ measurements [4]. The machine learning approach employed seven algorithms: Extremely Randomized Trees (ET), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Stacking Random Forest (SRF), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [4].

Performance Comparison (Root Mean Square Deviation - RMSD):

| Modeling Approach | Key Feature | Best Model | Performance (RMSD μmol/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regional Empirical Models | Ocean segmented into 5 biome-based regions | - | 1.641 - 2.701 |

| Machine Learning with Data Fusion | Single model for global ocean, no segmentation | XGBoost | 1.189 |

The XGBoost model, which bypassed the need for complex regional segmentation, outperformed all traditional regional empirical models, demonstrating the power of data fusion to create more accurate and universally applicable models [4].

Case Study 3: Hydrocarbon/Imide Ratio Prediction in Oils

Experimental Protocol: Research on oil industry samples compared five data fusion techniques applied to Mid-Infrared (MIR) and Raman spectroscopic data to predict a specific quality parameter (hydrocarbon/imide ratio of an additive) [5]. The fusion techniques were implemented at different levels: low (variable fusion), medium (model result fusion), high, and complex (ensemble learning with spectral data) [5].

Performance Comparison:

| Modeling Technique | Data Source | Relative Result |

|---|---|---|

| Mode A | Single Source (MIR only) | Baseline |

| Mode B | Single Source (Raman only) | Worse than Baseline |

| Mode C | Low-Level Fusion | Better than Baseline |

| Mode D | Intermediate-Level Fusion | Worse than Baseline |

| Mode E | High & Complex-Level Fusion | Best Results |

The results concluded that models using low, high, and complex data fusion techniques yielded better predictions than those built on single-source MIR or Raman data alone [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Data Fusion

For researchers aiming to implement data fusion frameworks, the following "research reagents" are essential conceptual components.

| Tool/Component | Function in Data Fusion Research |

|---|---|

| Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) | Provides a foundational statistical framework for understanding and deriving equivalence conditions between different fusion methods, particularly early and late fusion [2]. |

| Tree-Based Algorithms (XGBoost, LightGBM, RF) | Highly effective for integrating heterogeneous data sources and modeling complex, nonlinear relationships, often serving as strong baselines or final models in fusion pipelines [3] [4]. |

| Transformer Architectures | Advanced neural networks utilizing self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies and complex interactions between different data modalities without sequential processing constraints [6]. |

| Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) | A method for interpreting complex, fused models by quantifying the contribution of each input feature (from any source) to the final prediction, ensuring transparency [7] [6]. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression | A chemometrics staple used for modeling relationships between two data matrices (e.g., spectral data and quality parameters), frequently employed in low- and mid-level fusion for spectroscopic analysis [5]. |

The body of evidence confirms that data fusion strategies consistently outperform single-technique approaches, delivering substantial gains in predictive accuracy, robustness, and model transferability. The key to success lies in the strategic selection of the fusion method—early, intermediate, or late—which must be guided by the specific data characteristics, sample size, and the linear or nonlinear nature of the problem [2]. For researchers in drug development and beyond, mastering this selection paradigm is no longer a luxury but a necessity for unlocking the next frontier of predictive innovation.

In the pursuit of advanced predictive modeling, researchers and drug development professionals increasingly face a critical choice: whether to rely on single-data sources or integrate multiple modalities through data fusion. This guide examines the core fusion architectures—early, intermediate, and late fusion—that frame this decision within the broader thesis of predictive accuracy versus single-technique research. Technological advancements have generated vast quantities of multi-source heterogeneous data across biomedical domains, from genomic sequences and clinical variables to medical imaging and physiological time series [6] [8]. While single-modality analysis offers simplicity, it fundamentally limits a model's capacity to capture the complex, complementary information distributed across different data types [9].

Multimodal data fusion has emerged as a transformative paradigm to overcome these limitations. By strategically integrating diverse data sources—including clinical records, imaging, molecular profiles, and sensor readings—fusion architectures enable the development of more robust, accurate, and generalizable predictive models [10] [11]. This capability is particularly valuable in precision oncology, where integrating imaging, clinical, and genomic data has demonstrated significant improvements in cancer classification and survival prediction compared to unimodal approaches [9] [12] [8]. The core challenge lies in selecting the optimal fusion strategy that balances model complexity with predictive performance while accounting for domain-specific constraints.

This guide provides a systematic comparison of the three principal fusion architectures, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols. By objectively evaluating the performance of each fusion type against single-technique alternatives, we aim to equip researchers with the evidence needed to make informed decisions in their predictive modeling workflows.

Fusion Architecture Fundamentals

Definitions and Conceptual Frameworks

The three primary fusion strategies—early, intermediate, and late fusion—differ fundamentally in their approach to integrating information across modalities, each with distinct technical implementations and performance characteristics.

Early Fusion (Data-Level Fusion): This approach involves concatenating raw or preprocessed data from different modalities into a unified input vector before feeding it into a single model [2] [13]. For example, in biomedical applications, clinical variables, genomic data, and imaging features might be combined into one comprehensive input matrix. The defining characteristic of early fusion is its ability to learn complex interactions between modalities from the outset, as expressed by the generalized linear model formulation:

g_E(μ) = η_E = Σ(w_i * x_i)where all featuresx_ifrom different modalities are combined with weight coefficientsw_i[2].Intermediate Fusion (Feature-Level Fusion): This strategy processes each modality through separate feature extractors before combining the learned representations at an intermediate layer within the model architecture [10] [11]. Also known as joint fusion or model-level fusion, this approach preserves modality-specific characteristics while learning cross-modal interactions through specialized fusion layers. Intermediate fusion effectively balances the preservation of modality-specific features with the learning of joint representations, making it particularly valuable for capturing complex inter-modal relationships in biomedical contexts [10].

Late Fusion (Decision-Level Fusion): This method trains separate models on each modality independently and combines their predictions at the decision stage through a fusion function [12] [2] [8]. The mathematical formulation can be expressed as training sub-models for each modality:

g_Lk(μ) = η_Lk = Σ(w_jk * x_jk)fork = 1,2,...,Kmodalities, then aggregating the outputs through a fusion function:output_L = f(g_L1^{-1}(η_L1), g_L2^{-1}(η_L2), ..., g_LK^{-1}(η_LK))[2]. This approach offers strong resistance to overfitting, especially with imbalanced modality dimensionalities [8].

Architectural Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental workflow differences between the three core fusion architectures.

Performance Comparison: Fusion vs. Single-Modality Approaches

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Experimental evidence across multiple biomedical domains demonstrates that multimodal fusion approaches consistently outperform single-modality methods, though the optimal fusion strategy varies by application context and data characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Fusion Architectures Across Biomedical Domains

| Application Domain | Single-Modality Baseline (Performance) | Early Fusion (Performance) | Intermediate Fusion (Performance) | Late Fusion (Performance) | Optimal Fusion Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Survival Prediction [12] | Clinical data only (C-index: 0.76) | N/R | N/R | Clinical + Omics (C-index: 0.89) | Late Fusion |

| Chemical Engineering Project Prediction [6] | Traditional ML (Accuracy: ~71.6%) | N/R | Standard Transformer (Accuracy: ~84.9%) | N/R | Improved Transformer (Accuracy: 91.0%) |

| Prostate Cancer Classification [9] | Unimodal approaches (AUC: <0.85) | Common with CNNs (AUC: ~0.82-0.88) | Varied performance | Less common | Early/Intermediate Fusion |

| Multi-Omics Cancer Survival [8] | Multiple unimodal baselines | Lower vs. late fusion | Moderate performance | Consistently superior | Late Fusion |

| Biomedical Time Series [11] | Unimodal deep learning | Limited by misalignment | Superior accuracy & robustness | Moderate performance | Intermediate Fusion |

Table 2: Contextual Advantages and Limitations of Fusion Architectures

| Fusion Type | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Optimal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Fusion | Captures complex feature interactions immediately; Single model simplicity | Vulnerable to overfitting with high-dimensional data; Requires modality alignment | Low-dimensional, aligned modalities; Strong inter-modal correlations |

| Intermediate Fusion | Balances specificity and interaction; Flexible architecture design | Complex model design; Higher computational demand | Cross-modal relationship learning; Handling temporal misalignment |

| Late Fusion | Robust to overfitting; Handles data heterogeneity; Enables modality weighting | Cannot learn cross-modal interactions; Requires sufficient unimodal data | High-dimensional, heterogeneous data; Independent modality distributions |

Theoretical Performance Under varying Conditions

Research by [2] provides mathematical analysis of the conditions under which different fusion strategies excel, proposing an approximate equation for evaluating the accuracy of early and late fusion as a function of sample size, feature quantity, and modality number. Their work identifies a critical sample size threshold at which the performance dominance of early and late fusion models reverses:

- With small sample sizes relative to feature dimensions, late fusion consistently outperforms early fusion due to its resistance to overfitting [2].

- Early fusion theoretically outperforms late fusion in binary classification problems given a perfect model and sufficiently large sample size [2].

- The presence of nonlinear feature-label relationships can cause early fusion to fail, making late or intermediate fusion more appropriate for complex, nonlinear biomedical data [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Fusion Architectures in Survival Prediction

The experimental protocol for comparing fusion architectures in cancer survival prediction [12] [8] follows a rigorous methodology:

Data Collection and Preprocessing: Aggregate multi-omics data (transcripts, proteins, metabolites), clinical variables, and histopathology images from curated sources like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Implement appropriate normalization, batch effect correction, and missing data imputation.

Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction: Apply modality-specific feature selection to address high dimensionality. Common approaches include:

Model Training with Multiple Fusion Strategies:

- Early Fusion: Concatenate selected features from all modalities into a unified input matrix for a single survival model.

- Intermediate Fusion: Process each modality through separate subnetworks, then combine features using attention mechanisms or concatenation before the final prediction layer [10].

- Late Fusion: Train separate survival models for each modality, then combine predictions through weighted averaging or meta-learners [12] [8].

Evaluation and Validation: Assess performance using concordance index (C-index) with confidence intervals from multiple training-test splits, accounting for considerable uncertainty from different data partitions [8]. Additional evaluation includes calibration analysis and time-dependent AUC metrics.

Domain-Specific Implementation Variations

Across different biomedical applications, the core experimental protocol adapts to domain-specific requirements:

Biomedical Time Series Prediction [11]: Incorporates temporal alignment mechanisms and specialized architectures (LSTMs, Transformers) to handle varying sampling rates across physiological signals, clinical events, and medication records.

Medical Imaging Integration [14]: Employs convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for feature extraction from imaging data, followed by radiomics feature selection and habitat imaging analysis before fusion with clinical and genomic data.

Chemical Engineering Applications [6]: Utilizes improved Transformer architectures with multi-scale attention mechanisms to handle vastly different temporal hierarchies, from millisecond sensor readings to monthly progress reports.

The diagram below illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow for comparing fusion methodologies in biomedical research.

Successful implementation of fusion architectures requires careful selection of computational frameworks, data resources, and evaluation tools. The following table details essential components for constructing and validating multimodal fusion models.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Fusion Experiments

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Datasets | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Data Repositories | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [12] [8] | Provides curated multi-omics, clinical, and imaging data for cancer research | Benchmarking fusion models across diverse cancer types |

| PeMS Traffic Data [15] | Offers structured temporal data for long-term prediction validation | Testing fusion approaches on heterogeneous time series | |

| Computational Frameworks | Transformer Architectures [6] | Handles variable-length sequences and captures long-range dependencies | Processing data with vastly different sampling frequencies |

| Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Networks (AMFN) [11] | Dynamically captures inter-modal dependencies with attention mechanisms | Biomedical time series with misaligned modalities | |

| Evaluation Metrics | Concordance Index (C-index) [12] [8] | Evaluates ranking accuracy of survival predictions | Assessing clinical prediction models |

| SHAP/LIME Analysis [14] | Provides model interpretability and feature importance | Understanding fusion model decisions for clinical translation | |

| Fusion-Specific Libraries | AZ-AI Multimodal Pipeline [8] | Python library for multimodal feature integration and survival prediction | Streamlining preprocessing, fusion, and evaluation workflows |

The evidence consistently demonstrates that multimodal fusion architectures significantly outperform single-modality approaches across diverse biomedical applications, with performance improvements of 6-20% depending on the domain and data characteristics [6] [12] [8]. However, the optimal fusion strategy is highly context-dependent, requiring careful consideration of data properties and application requirements.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the following strategic guidelines emerge from experimental evidence:

Prioritize Late Fusion when working with high-dimensional data, limited samples, or significant heterogeneity across modalities, particularly in survival prediction and multi-omics integration [12] [8].

Select Intermediate Fusion when capturing complex cross-modal relationships is essential, and sufficient data exists to train more sophisticated architectures, especially for biomedical time series and imaging applications [10] [11].

Consider Early Fusion primarily for low-dimensional, well-aligned modalities where capturing fine-grained feature interactions is critical to prediction performance [2] [13].

Implement Rigorous Evaluation practices including multiple data splits, confidence intervals for performance metrics, and comparisons against unimodal baselines to ensure meaningful conclusions about fusion effectiveness [8].

The strategic integration of multimodal data through appropriate fusion architectures represents a substantial advancement over single-technique research, offering enhanced predictive accuracy and more robust models for critical applications in drug development and precision medicine. As fusion methodologies continue to evolve, particularly with advances in attention mechanisms and transformer architectures, their capacity to translate heterogeneous data into actionable insights will further expand, solidifying their role as essential tools in biomedical research.

In predictive research, single-source data or unimodal models often struggle with inherent uncertainties, including high dimensionality, low signal-to-noise ratios, and data heterogeneity. These challenges are particularly acute in high-stakes fields like drug development and precision oncology, where accurate predictions directly impact patient outcomes and therapeutic discovery. Data fusion has emerged as a transformative methodology that systematically mitigates these uncertainties by integrating complementary information from multiple sources, features, or models. The core theoretical advantage of fusion lies in its ability to synthesize disparate evidence, thereby reducing variance, counteracting biases in individual data sources, and producing more robust and reliable predictive outputs. This review synthesizes current evidence and theoretical frameworks demonstrating how fusion techniques enhance predictive accuracy and reliability compared to single-modality approaches, with particular emphasis on applications relevant to biomedical research and pharmaceutical development.

Theoretical Foundations: How Fusion Mitigates Uncertainty

Core Mechanisms of Uncertainty Reduction

Data fusion reduces uncertainty through several interconnected theoretical mechanisms. First, it addresses the complementarity principle, where different data modalities capture distinct aspects of the underlying system. For instance, in cancer survival prediction, genomic data may reveal mutational drivers, clinical variables provide physiological context, and proteomic measurements offer functional insights. Fusion integrates these complementary perspectives, creating a more complete representation of the phenomenon than any single source can provide [8]. Second, fusion leverages information redundancy when multiple sources provide overlapping evidence about the same underlying factor. This redundancy allows the system to cross-validate information, reducing the impact of noise and measurement errors in individual sources while increasing overall confidence in the consolidated output [2] [8].

The mathematical relationship between data fusion and uncertainty reduction can be conceptualized through statistical learning theory. In late fusion, for example, where predictions from multiple unimodal models are aggregated, the variance of the fused prediction can be substantially lower than that of individual models, particularly when the errors between models are uncorrelated. This variance reduction directly decreases prediction uncertainty and enhances generalizability, especially valuable when working with limited sample sizes common in biomedical research [2] [8].

Categorical Framework of Fusion Techniques

Fusion methodologies are systematically categorized based on the stage at which integration occurs, each with distinct theoretical properties affecting uncertainty reduction:

- Early Fusion (Data-Level Fusion): Raw data from multiple sources are concatenated before feature extraction or model training. This approach preserves potential interactions between raw data sources but risks increased dimensionality and overfitting, particularly with small sample sizes [2] [8].

- Intermediate Fusion (Feature-Level Fusion): Features are first extracted from each data source independently, then integrated into a shared representation space. This balances specificity with joint learning, allowing the model to discover complex cross-modal interactions while maintaining some modality-specific processing [2].

- Late Fusion (Decision-Level Fusion): Separate models are trained on each data source, and their predictions are aggregated. This approach is particularly robust to data heterogeneity and missing modalities, as it accommodates different model architectures tailored to each data type [2] [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Fusion Strategies and Their Properties

| Fusion Type | Integration Stage | Theoretical Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Fusion | Raw data input | Preserves cross-modal interactions; Maximizes theoretical information | Multimodal data with strong interconnections; Large sample sizes |

| Intermediate Fusion | Feature representation | Balances specificity and joint learning; Handles some heterogeneity | Hierarchical data structures; Moderate sample sizes |

| Late Fusion | Model predictions | Robust to data heterogeneity; Resistant to overfitting | High-dimensional data with small samples; Missing modalities |

Experimental Evidence: Quantitative Comparisons of Fusion Performance

Fusion in Healthcare and Disease Prediction

Substantial empirical evidence demonstrates fusion's superiority over single-modality approaches across healthcare domains. A fusion-based machine learning approach for diabetes identification, combining Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) classifiers, achieved a 94.67% prediction accuracy, exceeding the performance of either classifier alone and outperforming the best previously reported model by approximately 1.8% [16]. This fusion architecture specifically enhanced both sensitivity (89.23%) and specificity (97.32%), indicating more reliable classification across different patient subgroups [16].

In oncology, a comprehensive machine learning pipeline for multimodal data fusion analyzed survival prediction in cancer patients using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data, incorporating transcripts, proteins, metabolites, and clinical factors [8]. The research demonstrated that late fusion models "consistently outperformed single-modality approaches in TCGA lung, breast, and pan-cancer datasets, offering higher accuracy and robustness" [8]. This performance advantage was particularly pronounced given the challenging characteristics of biomedical data, including high dimensionality, small sample sizes, and significant heterogeneity across modalities.

Cross-Domain Validation of Fusion Efficacy

Beyond healthcare, fusion methods demonstrate similar advantages in diverse predictive domains. In financial market prediction, fusion techniques that integrate numerical data with textual information from news and social media have shown "substantial improvements in profit" and forecasting accuracy [17]. A systematic review of fusion techniques in this domain between 2016-2025 highlights how integrating disparate data sources enhances prediction reliability by capturing both quantitative market data and qualitative sentiment indicators [17].

In chemical engineering construction projects, an improved Transformer architecture for multi-source heterogeneous data fusion achieved "prediction accuracies exceeding 91% across multiple tasks," representing improvements of "up to 19.4% over conventional machine learning techniques and 6.1% over standard Transformer architectures" [6]. This approach successfully integrated structured numerical measurements, semi-structured operational logs, and unstructured textual documentation, demonstrating fusion's capacity to handle extreme data heterogeneity while reducing predictive uncertainty.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Domains

| Application Domain | Single-Model Performance | Fusion Approach Performance | Performance Gain | Key Fusion Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Identification | 92.8% (DELM) [16] | 94.67% [16] | +1.87% | Classifier Fusion (SVM+ANN) |

| Cancer Survival Prediction | Variable by modality [8] | Consistently superior [8] | Significant | Late Fusion |

| Chemical Engineering Project Management | ~76% (Conventional ML) [6] | 91%+ [6] | +15% | Transformer-based Fusion |

| Financial Market Forecasting | Baseline single-source [17] | Substantially improved profit [17] | Significant | Multimodal Text-Data Fusion |

Methodological Protocols: Implementing Fusion Strategies

Experimental Workflow for Fusion Analysis

The implementation of effective fusion strategies follows systematic methodological protocols. The AstraZeneca–artificial intelligence (AZ-AI) multimodal pipeline for survival prediction in cancer patients provides a representative framework for fusion implementation [8]. This pipeline encompasses data preprocessing, multiple fusion strategies, diverse feature reduction approaches, and rigorous evaluation metrics, offering a standardized methodology for comparing fusion efficacy against unimodal benchmarks.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Multimodal Data Fusion

Fusion Selection Paradigm and Critical Thresholds

Research has established theoretical frameworks to guide the selection of appropriate fusion strategies based on dataset characteristics. A comparative analysis of three data fusion methods proposed a "critical sample size threshold at which the performance dominance of early fusion and late fusion models undergoes a reversal" [2]. This paradigm enables researchers to select the optimal fusion approach before task execution, improving computational efficiency and predictive performance.

The theoretical analysis demonstrates that under generalized linear models, early and late fusion achieve equivalence under specific mathematical conditions, but early fusion may fail when nonlinear feature-label relationships exist across modalities [2]. This work further provides an "approximate equation for evaluating the accuracy of early and late fusion methods as a function of sample size, feature quantity, and modality number" [2], offering a principled basis for fusion strategy selection rather than relying solely on empirical comparisons.

Implementation Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Data Fusion

Successful implementation of fusion strategies requires both computational frameworks and analytical methodologies. The following toolkit outlines essential components for developing and evaluating fusion-based predictive systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fusion Implementation

| Tool/Component | Category | Function in Fusion Research | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Pipeline Architecture | Computational Framework | Standardizes preprocessing, fusion strategies, and evaluation for reproducible comparison | AZ-AI Multimodal Pipeline [8] |

| Feature Selection Methods | Analytical Method | Reduces dimensionality while preserving predictive signals; mitigates overfitting | Pearson/Spearman correlation, Mutual Information [8] |

| Hybrid Validation Protocols | Evaluation Framework | Combines cross-validation with sampling methods to assess generalizability | Fusion Sampling Validation (FSV) [18] |

| Transformer Architectures | Modeling Framework | Handles heterogeneous data types through unified embeddings and attention mechanisms | Improved Transformer with multi-scale attention [6] |

| Ensemble Survival Models | Predictive Modeling | Integrates multiple survival models for more robust time-to-event predictions | Gradient boosting, random forests [8] |

Diagram 2: Architectural Comparison of Early vs. Late Fusion Strategies

The theoretical principles and empirical evidence consolidated in this review demonstrate that data fusion provides systematic advantages for reducing predictive uncertainty and increasing reliability across multiple domains, particularly in biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. The performance gains observed in diabetes identification, cancer survival prediction, and drug development contexts consistently show that strategically integrated multimodal information outperforms single-source approaches. The critical theoretical insight is that fusion mitigates the limitations and uncertainties inherent in individual data sources by leveraging complementarity, redundancy, and error independence across modalities.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the importance of adopting fusion methodologies in predictive modeling workflows. The availability of standardized pipelines, theoretical selection frameworks, and specialized architectures like Transformers for heterogeneous data makes fusion increasingly accessible for practical implementation. As multimodal data generation continues to accelerate in life sciences, fusion approaches will become increasingly essential for extracting reliable insights, reducing decision uncertainty, and advancing precision medicine initiatives. Future research directions include developing more sophisticated cross-modal alignment techniques, adaptive fusion mechanisms that dynamically weight source contributions based on quality and relevance, and enhanced interpretability frameworks to build trust in fused predictive systems.

The modern scientific and business landscapes are defined by an explosion of data, generated from a proliferating number of disparate sources. In this context, data integration—the process of combining and harmonizing data from multiple sources, formats, or systems into a unified, coherent dataset—has transitioned from a technical convenience to a strategic necessity [19]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this is not merely an IT challenge but a fundamental component of accelerating discovery and enhancing predictive accuracy. The central thesis of this guide is that integrated data solutions, particularly through advanced fusion methods, consistently demonstrate superior predictive performance compared to single-technique or single-source approaches. This is evidenced by a growing body of research across fields from genomics to clinical drug development, where the fusion of disparate data modalities is unlocking new levels of insight, robustness, and transferability in predictive models [3] [20]. This guide objectively compares the performance of integrated data solutions against traditional alternatives, providing the detailed experimental data and methodologies needed to inform the selection of tools and frameworks for high-stakes research environments.

The Integrated Data Landscape: Tools and Platforms

The market for data integration tools is diverse, with platforms engineered for specific use cases such as analytics, operational synchronization, or enterprise-scale ETL (Extract, Transform, Load). The choice of tool is critical and should be driven by the primary intended outcome [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Data Integration Tool Categories

| Category | Representative Tools | Core Strength | Ideal Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modern ELT for Analytics | Fivetran, Airbyte, Estuary [19] [21] [22] | Reliably moving data from sources to a central data warehouse for analysis [21]. | Dashboards, AI/ML features, historical analysis [21]. |

| Real-Time Operational Sync | Stacksync [21] | Maintaining real-time, bi-directional data consistency across live operational systems (e.g., CRM, ERP) with conflict resolution [21]. | Operational consistency, accurate customer records, synchronized orders [21]. |

| Enterprise ETL & iPaaS | Informatica PowerCenter, MuleSoft, Talend [19] [21] | Handling complex, high-volume data transformation and integration requirements in large IT environments [19] [21]. | Complex data workflows, application networking, large-scale batch processing. |

Selecting the right platform involves evaluating key technical criteria. Connectivity is paramount; the tool must offer pre-built connectors to your necessary data sources and APIs [19]. Scalability ensures the platform can handle growing data volumes, while data quality and governance capabilities like profiling, cleansing, and lineage tracking are essential for research integrity [19] [23]. Finally, the movement model—whether it's batch ETL, ELT (Extract, Load, Transform), or real-time Change Data Capture (CDC)—must align with the latency requirements of your projects [21] [22].

Data Fusion vs. Single-Technique Approaches: Experimental Evidence

The superiority of integrated data solutions is not merely theoretical but is being rigorously demonstrated through controlled experiments across multiple scientific domains. The following section summarizes key experimental findings and protocols that directly compare fused data approaches against single-modality baselines.

Evidence from Genomic and Phenotypic Selection

A groundbreaking study in plant science introduced the GPS framework, a novel data fusion strategy for integrating genomic and phenotypic data to improve genomic selection (GS) and phenotypic selection (PS) for complex traits [3]. The researchers systematically compared three fusion strategies—data fusion, feature fusion, and result fusion—against the best single-technique models across four crop species (maize, soybean, rice, and wheat).

Table 2: Predictive Accuracy in Genomic and Phenotypic Selection [3]

| Model Type | Specific Model | Key Performance Finding | Comparative Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best Single-Technique (GS) | LightGBM | Baseline accuracy for Genomic Selection | -- |

| Best Single-Technique (PS) | Lasso | Baseline accuracy for Phenotypic Selection | -- |

| Data Fusion Model | Lasso_D | Achieved the highest accuracy of all tested models | 53.4% higher than best GS model (LightGBM); 18.7% higher than best PS model (Lasso) [3]. |

Experimental Protocol for Genomic-Phenotypic Fusion [3]:

- Datasets: Large-scale datasets from four crop species: maize, soybean, rice, and wheat.

- Models: A suite of models was employed, including statistical approaches (GBLUP, BayesB), machine learning models (Lasso, RF, SVM, XGBoost, LightGBM), a deep learning method (DNNGP), and a phenotype-assisted model (MAK).

- Fusion Strategies:

- Data Fusion: Raw genomic and phenotypic data were concatenated into a single input vector for model training.

- Feature Fusion: Features were learned from genomic and phenotypic data separately and then fused for predictive classification.

- Result Fusion: Separate models were trained on genomic and phenotypic data, and their decisions were aggregated for a final prediction.

- Evaluation: Predictive accuracy for complex traits was the primary metric. The robustness of the top-performing model (Lasso_D) was further tested with varying sample sizes and SNP densities, and its transferability was assessed using multi-environmental data.

Evidence from Chemical Engineering and Multi-Modal Prediction

Research in chemical engineering construction further validates the advantages of integrated data solutions. A 2025 study developed a framework for multi-source heterogeneous data fusion using an improved Transformer architecture to integrate diverse data types, including structured numerical measurements, semi-structured operational logs, and unstructured textual documentation [6].

Table 3: Predictive Modeling Accuracy in Chemical Engineering [6]

| Modeling Approach | Reported Prediction Accuracy | Comparative Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional Machine Learning | Baseline | Up to 19.4% lower than the proposed fusion model |

| Standard Transformer Architecture | Baseline | 6.1% lower than the improved fusion model |

| Improved Transformer with Multi-Source Data Fusion | Exceeded 91% across multiple tasks (progress, quality, risk) | Represented an improvement of up to 19.4% over conventional ML and 6.1% over standard Transformers [6]. |

Experimental Protocol for Multi-Modal Transformer Fusion [6]:

- Data: Multi-source heterogeneous data from chemical engineering construction projects, including sensor readings, progress reports, and material logs.

- Model Architecture: An improved Transformer model with a domain-specific multi-scale attention mechanism was used. This mechanism explicitly models temporal hierarchies to handle data streams with vastly different sampling frequencies.

- Key Innovations:

- Contrastive Cross-Modal Alignment: This framework learns semantic correspondences between heterogeneous modalities without manually crafted feature mappings.

- Adaptive Weight Allocation: This algorithm dynamically adjusts the contribution of each data source based on real-time quality assessment and task-specific relevance.

- Evaluation: The model was simultaneously evaluated on progress estimation, quality assessment, and risk evaluation tasks. It also demonstrated robust anomaly detection (exceeding 92% detection rates) and real-time processing performance (under 200 ms).

Theoretical Underpinnings of Fusion Performance

The empirical results are supported by theoretical analyses that explain why and when different fusion methods excel. A comparative analysis of early, late, and gradual fusion methods derived equivalence conditions between early and late fusion within generalized linear models [2]. Crucially, the study proposed an equation to evaluate the accuracy of early and late fusion as a function of sample size, feature quantity, and modality number, identifying a critical sample size threshold at which the performance dominance of early and late fusion models reverses [2]. This provides a principled basis for selecting a fusion method prior to task execution, moving beyond reliance on experimental comparisons alone.

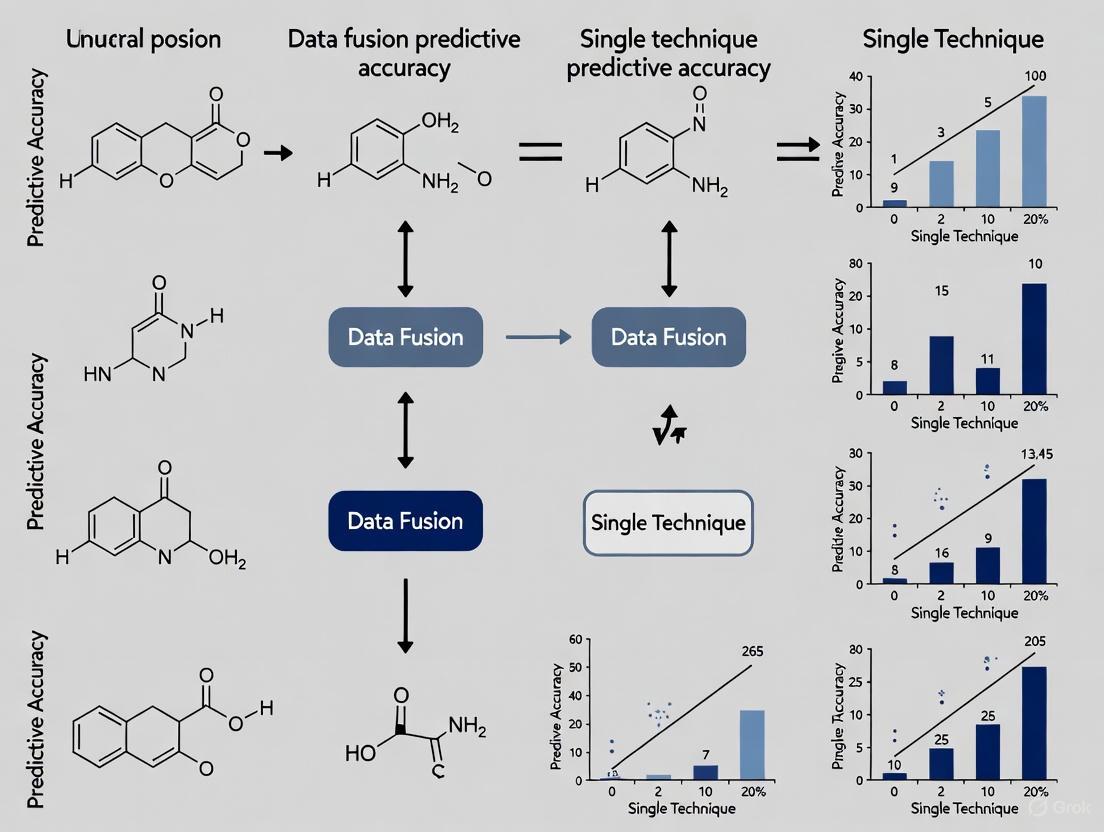

Visualization of Data Fusion Methodologies

The following diagrams illustrate the core architectures and workflows of the data fusion methods discussed in the experimental evidence.

Conceptual Data Fusion Workflow

Technical Fusion Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Platforms

For researchers embarking on data integration projects, the following tools and platforms constitute the modern "reagent kit" for building robust, integrated data solutions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Data Integration

| Tool / Solution | Category / Function | Brief Explanation & Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fivetran [19] [21] | Automated ELT Pipeline | A fully managed service for automating data movement from sources to a data warehouse. Ideal for analytics teams needing reliable, hands-off data ingestion for downstream analysis. |

| Airbyte [21] [22] | Open-Source ELT | Provides flexibility and cost-effectiveness with a large library of connectors. Suited for technical teams requiring control over their data pipelines and wishing to avoid vendor lock-in. |

| Informatica PowerCenter [19] [21] | Enterprise ETL | A robust, scalable solution for complex, high-volume data transformation workflows. Meets the needs of large enterprises in regulated industries like healthcare and finance. |

| Estuary [22] | Real-Time ELT/CDC | Supports both real-time and batch data integration with built-in data replay. Fits projects requiring low-latency data capture and synchronization for real-time analytics. |

| Stacksync [21] | Real-Time Operational Sync | A platform engineered for bi-directional synchronization between live systems (e.g., CRM ERP). Solves the problem of operational data inconsistency with conflict resolution. |

| Transformer Architectures [6] | Multi-Modal ML Framework | Deep learning models, particularly those with enhanced attention mechanisms, are pivotal for fusing heterogeneous data (text, numerical, sequential) into a unified representation for prediction. |

| Causal Machine Learning (CML) [20] | Causal Inference | Methods like targeted maximum likelihood estimation and doubly robust inference integrate RCT data with Real-World Data (RWD) to estimate causal treatment effects and identify patient subgroups. |

The collective evidence from genomics, chemical engineering, and clinical science presents a compelling case: the future of predictive modeling and scientific discovery is inextricably linked to the ability to effectively integrate and fuse disparate data sources. The experimental data consistently shows that integrated data solutions can achieve significant improvements in accuracy—ranging from 6.1% to over 50%—compared to single-technique approaches [3] [6]. This performance gain is coupled with enhanced robustness, transferability, and the ability to model complex, real-world systems more faithfully. For the modern researcher, proficiency with the tools and methodologies of data fusion is no longer a niche skill but a core component of the scientific toolkit, essential for driving innovation and achieving reliable, impactful results.

Fusion in Action: Methodologies for Integrating Multimodal Biomedical Data

In the evolving landscape of data-driven research, the limitations of unimodal analysis have become increasingly apparent. Data fusion, the process of integrating multiple data sources to produce more consistent, accurate, and useful information than that provided by any individual source, has emerged as a critical methodology across scientific disciplines [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting an appropriate fusion strategy is paramount, as it directly impacts the predictive accuracy and reliability of analytical models. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the three primary fusion levels—data-level (early), feature-level (intermediate), and decision-level (late) fusion—framed within the broader thesis of how multimodal integration enhances predictive performance compared to single-technique approaches.

The fundamental premise of data fusion is that different data sources often provide complementary information [24]. In a drug development context, this could involve integrating genomic data, clinical variables, and high-resolution imaging to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms or treatment effects. The strategic combination of these disparate data types can reveal interactions and patterns that remain obscured when modalities are analyzed independently.

Theoretical Foundations and Classification

Data fusion techniques are systematically classified based on the processing stage at which integration occurs. The most prevalent framework in clinical and scientific research distinguishes between data-level, feature-level, and decision-level fusion [25] [24]. Data-level fusion (also called early fusion) combines raw data from multiple sources before feature extraction [26]. Feature-level fusion (intermediate fusion) integrates processed features extracted from each modality separately [25]. Decision-level fusion (late fusion) combines outputs from multiple classifiers, each trained on different data modalities [2].

A more detailed conceptual model, established by the Joint Directors of Laboratories (JDL), further categorizes data fusion into five progressive levels: source preprocessing (Level 0), object refinement (Level 1), situation assessment (Level 2), impact assessment (Level 3), and process refinement (Level 4) [24]. This multi-layered approach facilitates increasingly sophisticated inferences, moving from basic data correlation to high-level impact assessment and resource management.

Table 1: Classification Frameworks for Data Fusion

| Classification Basis | Categories | Description | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abstraction Level [24] | Data/Input-Level | Fusion of raw or minimally processed data | Combines sensor readings or raw images |

| Feature-Level | Fusion of extracted features | Merges shape, texture, or statistical features | |

| Decision-Level | Fusion of model outputs or decisions | Averages or weights classifier predictions | |

| Dasarathy's Model [24] | Data In - Data Out (DAI-DAO) | Input & output are raw data | Signal/image processing algorithms |

| Data In - Feature Out (DAI-FEO) | Input is raw data, output is features | Feature extraction techniques | |

| Feature In - Feature Out (FEI-FEO) | Input & output are features | Intermediate-level fusion | |

| Feature In - Decision Out (FEI-DEO) | Input is features, output is decisions | Standard classification systems | |

| Decision In - Decision Out (DEI-DEO) | Input & output are decisions | Ensemble methods, model stacking | |

| Data Relationships [24] | Complementary | Data represents different parts of a scene | Non-overlapping sensor fields of view |

| Redundant | Data provides overlapping information | Multiple sensors measuring same parameter | |

| Cooperative | Data combined into new, more complex information | Multi-modal (e.g., audio-video) fusion |

The theoretical relationship between early (data-level) and late (decision-level) fusion has been formally explored within generalized linear models. Research indicates that under certain conditions, particularly with sufficient sample size and specific model configurations, early and late fusion can be mathematically equivalent [2]. However, early fusion may fail to capture complex relationships when nonlinear feature-label associations exist across modalities [2].

Comparative Analysis of Fusion Strategies

Data-Level (Early) Fusion

Data-level fusion involves the direct combination of raw data from multiple sources into a single, coherent dataset before any significant feature extraction or modeling occurs [26]. This approach is also commonly referred to as early fusion or input fusion [25].

Mechanism and Workflow: The process typically begins with the temporal and spatial registration of data from different sources to ensure alignment. The core step is the concatenation or aggregation of these aligned raw data inputs into a unified structure. This combined dataset then serves as the input for a single, monolithic model which handles both the learning of cross-modal relationships and the final prediction [27].

Advantages: The primary strength of data-level fusion lies in its potential to preserve all information present in the original data. By combining data at the rawest level, the model has direct access to the complete dataset, which, in theory, allows it to learn complex, low-level interactions between modalities that might be lost during pre-processing or feature extraction [26]. The workflow is also relatively straightforward, requiring the training and maintenance of only one model.

Disadvantages and Challenges: A significant drawback is the curse of dimensionality; merging raw data can create very high-dimensional input vectors, which increases the risk of overfitting, especially with limited training samples [26]. This approach is also highly susceptible to data quality issues like noise and misalignment, as errors in one modality can directly corrupt the fused dataset. Furthermore, data-level fusion is inflexible, as adding a new data source typically requires rebuilding the entire dataset and retraining the model from scratch.

Feature-Level (Intermediate) Fusion

Feature-level fusion, or intermediate fusion, strikes a balance between the early and late approaches. Here, features are first extracted independently from each data source, and these feature vectors are then combined into a joint representation before being fed into a classifier [25].

Mechanism and Workflow: The process involves two key stages. First, modality-specific features are learned or engineered separately. In deep learning contexts, this is often done using dedicated neural network branches for each data type. Second, these feature sets are integrated through methods like concatenation, element-wise addition, or more sophisticated attention-based mechanisms that weight the importance of different features [25]. The fused feature vector is then processed by a final classification network.

Advantages: This strategy allows the model to learn rich inter-modal interactions at a meaningful abstraction level, without the noise and dimensionality problems of raw data fusion [25] [27]. It is more flexible than data-level fusion, as individual feature extractors can be updated independently. Hierarchical and attention-based fusion techniques within this category can model complex, non-linear relationships between features from different sources [25].

Disadvantages and Challenges: The main challenge is the increased architectural complexity, requiring careful design of the fusion layer (e.g., choosing between concatenation, attention, etc.) [25]. It also demands that all modalities are available during training to learn the cross-modal correlations, and performance can be sensitive to the quality and scale of the initial feature extraction.

Decision-Level (Late) Fusion

Decision-level fusion, known as late fusion, is a modular approach where separate models are trained for each data modality, and their individual predictions are aggregated to form a final decision [2] [26].

Mechanism and Workflow: In this strategy, a dedicated classifier is trained on each modality independently. At inference time, each model processes its respective input and outputs a prediction (e.g., a class probability or a regression value). These individual decisions are then combined using an aggregation function, which can be as simple as a weighted average or majority voting, or a more complex meta-classifier that learns to weigh the models based on their reliability [2] [27].

Advantages: Late fusion offers superior modularity and flexibility. New data sources can be incorporated by simply adding a new model and including its output in the aggregation function, without retraining the existing system [26]. It also avoids the dimensionality issues of early fusion and allows for the use of highly specialized, optimized models for each data type. This approach is naturally robust to missing modalities, as the system can still function, albeit with potentially reduced accuracy, if one model's input is unavailable.

Disadvantages and Challenges: The most significant limitation is the potential loss of inter-modality information. Because models are trained in isolation, crucial cross-modal dependencies (e.g., the correlation between a specific genetic marker and a visual symptom) may not be captured [26]. Training and maintaining multiple models can also be computationally expensive and logistically complex.

Diagram 1: Architectural comparison of data fusion strategies, showing the stage at which fusion occurs in each paradigm.

Table 2: Strategic Comparison of Data Fusion Levels

| Characteristic | Data-Level (Early) Fusion | Feature-Level (Intermediate) Fusion | Decision-Level (Late) Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fusion Stage | Input level | Feature level | Decision level |

| Information Preservation | High (raw data) | Moderate (processed features) | Low (model outputs) |

| Inter-Modality Interaction | Direct and potentially comprehensive | Learned and hierarchical | Limited or none |

| Dimensionality | Very High | Moderate | Low |

| Flexibility to New Modalities | Low (requires full retraining) | Moderate (may require fusion layer adjustment) | High (add new model) |

| Robustness to Missing Data | Low | Low | High |

| Computational Complexity | Single, potentially complex model | Multiple feature extractors + fusion network | Multiple independent models |

| Implementation Complexity | Low to Moderate | High | Moderate |

Experimental Evidence and Performance Comparison

Key Experimental Protocols

Empirical evaluations across diverse fields consistently demonstrate the performance advantages of data fusion over single-modality approaches. A rigorous experimental protocol for comparing fusion strategies typically involves several key stages.

First, data acquisition and preprocessing must be standardized. For instance, in a study on genomic and phenotypic selection (GPS), genomic data (e.g., SNP markers) and phenotypic data (e.g., crop yield, plant height) were collected from multiple crop species including maize, soybean, rice, and wheat [3]. Similarly, a study on Normal Tissue Complication Probability (NTCP) modeling for osteoradionecrosis used clinical variables (demographic and treatment data) and mandibular radiation dose distribution volumes (dosiomics) [28].

The core of the protocol involves model training and validation. Researchers typically implement all three fusion strategies using consistent underlying algorithms (e.g., Lasso, Random Forests, SVM, or deep learning architectures like 3D DenseNet) to ensure fair comparison [3] [28]. Performance is evaluated through rigorous cross-validation, measuring metrics such as accuracy, area under the curve (AUC), calibration, and robustness to varying sample sizes or data quality.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Recent experimental findings provide compelling evidence for the superior predictive accuracy of data fusion compared to single-source techniques.

Table 3: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Domains

| Application Domain | Superior Fusion Strategy | Performance Gain Over Best Single-Source Model | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic & Phenotypic Selection (GPS) in Crops [3] | Data-Level (Early) Fusion | 53.4% improvement over best genomic model; 18.7% over best phenotypic model | Lasso_D model showed high accuracy with sample sizes as small as 200; robust to SNP density variations |

| Mandibular Osteoradionecrosis NTCP Modelling [28] | Decision-Level (Late) Fusion | Superior discrimination and calibration vs. single-modality models | Late fusion outperformed joint fusion; no significant discrimination difference between strategies |

| Theoretical Analysis (Generalized Linear Models) [2] | Context-Dependent | Critical sample size threshold for performance reversal | Early fusion outperforms with small samples; late fusion excels beyond critical sample size |

In the agricultural study, the data fusion framework (GPS) was tested with an extensive suite of models including GBLUP, BayesB, Lasso, RF, SVM, XGBoost, LightGBM, and DNNGP. The data-level fusion strategy consistently achieved the highest accuracy, with the top-performing model (Lasso_D) demonstrating exceptional robustness even with limited sample sizes and varying data conditions [3].

In the medical domain, a comparative study on osteoradionecrosis NTCP modelling found that while late fusion exhibited superior discrimination and calibration, joint (intermediate) fusion achieved a more balanced distribution of predicted probabilities [28]. This highlights that the optimal strategy may depend on the specific performance metric prioritized by researchers.

A crucial theoretical insight explains these contextual results: the existence of a critical sample size threshold at which the performance dominance of early and late fusion reverses [2]. This provides a mathematical foundation for why different strategies excel under different data conditions, moving the field beyond trial-and-error selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing effective data fusion requires both conceptual understanding and practical tools. The following table outlines essential "research reagents" - key algorithms, software, and data management solutions - that form the foundation for data fusion experiments in scientific research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Data Fusion Experiments

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Data Fusion Research |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Lasso, Random Forests (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM) [3] | Base models for feature selection and classification in fusion frameworks |

| Deep Learning Architectures | 3D DenseNet-40 [28], DNNGP [3] | Processing complex image data (e.g., dose distributions); genomic prediction |

| Ensemble Methods | Weighted Averaging, Stacking, Majority Voting [26] | Aggregating predictions from multiple models in late fusion |

| Fusion-Specific AI | Diag2Diag AI [29] [30] | Generating synthetic sensor data to recover missing information |

| Data Platforms & Ecosystems | Fusion Energy Data Ecosystem and Repository (FEDER) [31] | Unified platform for sharing standardized fusion data across institutions |

| Feature Extraction Techniques | Attention Mechanisms [25], Hierarchical Fusion | Identifying and weighting important features across modalities |

Specialized tools like the Diag2Diag AI demonstrate advanced fusion applications, capable of generating synthetic sensor data to compensate for missing diagnostic information in complex systems like fusion energy reactors [29] [30]. This approach has particular relevance for pharmaceutical research where complete multimodal datasets are often difficult to obtain.

Similarly, community-driven initiatives like the Fusion Energy Data Ecosystem and Repository (FEDER) highlight the growing importance of standardized data platforms for accelerating research through shared resources and reproducible workflows [31]. While developed for fusion energy, this concept directly translates to drug development where multi-institutional collaboration is common.

The comparative analysis of data-level, feature-level, and decision-level fusion strategies reveals a consistent theme: multimodal data fusion generally enhances predictive accuracy compared to single-technique approaches, but the optimal strategy is highly context-dependent. Experimental evidence from diverse fields including agriculture, medical physics, and energy research demonstrates performance improvements ranging from approximately 19% to over 53% when employing an appropriate fusion strategy compared to the best single-source model [3] [28].

The selection of an appropriate fusion strategy depends on multiple factors, including data characteristics (volume, quality, modality relationships), computational resources, and project requirements for flexibility and robustness. Data-level fusion often excels with smaller datasets and strong inter-modal dependencies [2] [3]. Feature-level fusion offers a balanced approach for capturing complex interactions without the dimensionality curse of raw data fusion [25]. Decision-level fusion provides maximum flexibility and robustness, particularly valuable when dealing with missing data or frequently added new modalities [28] [26].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the importance of systematically evaluating multiple fusion strategies rather than relying on a default approach. The emerging paradigm of fusion method selection, guided by theoretical principles like critical sample size thresholds and data relationship classifications, promises to enhance research efficiency and predictive accuracy in the increasingly multimodal landscape of scientific inquiry [2] [24].

In the fields of genomics and drug development, a significant challenge persists: connecting an organism's genetic blueprint (genotype) to its observable characteristics (phenotype). Traditional approaches that rely on a single data type often yield incomplete insights, especially for complex traits influenced by multiple genetic and environmental factors [32]. Data integration is increasingly becoming an essential tool to cope with the ever-increasing amount of data, to cross-validate noisy datasets, and to gain broad interdisciplinary views of large genomic and proteomic datasets [32].

This guide objectively compares the performance of a data fusion strategy against single-technique research, framing the discussion within the broader thesis that integrating disparate data sources provides superior predictive accuracy than any individual dataset alone. The overarching goals of data integration are to obtain more precision, better accuracy, and greater statistical power [32]. By synthesizing methodologies and evidence from current research, we provide a framework for researchers and scientists to construct effective fusion pipelines, thereby unlocking more reliable and actionable biological insights.

Data Fusion Strategies: A Comparative Framework

Data fusion methods can be systematically classified based on the stage at which integration occurs. Understanding this hierarchy is crucial for selecting the appropriate architectural strategy for a genomic-phenotypic pipeline [2].

Table: Classification of Data Fusion Strategies

| Fusion Type | Alternative Names | Stage of Integration | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Fusion | Data-Level Fusion | Input Stage | Raw or pre-processed data from multiple sources are concatenated into a single feature set before model input. |

| Intermediate Fusion | Feature-Level Fusion | Processing Stage | Features are extracted from each data source independently first, then combined into a joint feature space. |

| Late Fusion | Decision-Level Fusion | Output Stage | Separate models are trained on each data type, and their predictions are aggregated for a final decision. |

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and data flow for these three primary fusion strategies:

Performance Comparison: Fusion vs. Single-Technique Approaches

Recent large-scale studies provide compelling experimental data on the performance benefits of data fusion. A 2025 study introduced the GPS (Genomic and Phenotypic Selection) framework, rigorously testing it on datasets from four crop species: maize, soybean, rice, and wheat [3]. The study compared three fusion strategies—data fusion (early), feature fusion (intermediate), and result fusion (late)—against standalone Genomic Selection (GS) and Phenotypic Selection (PS) models using a suite of statistical and machine learning models [3].

Table: Predictive Performance Comparison of Fusion vs. Single-Technique Models

| Model Type | Specific Model | Key Performance Finding | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best Data Fusion Model | Lasso_D | Improved accuracy by 53.4% vs. best GS model and 18.7% vs. best PS model [3]. | Highest overall accuracy, robust to sample size and SNP density variations. |

| Best Genomic Selection (GS) Model | LightGBM | Used as baseline for GS accuracy [3]. | Effective for purely genetic prediction, but outperformed by fusion. |

| Best Phenotypic Selection (PS) Model | Lasso | Used as baseline for PS accuracy [3]. | Effective for trait correlation, but outperformed by fusion. |

| Feature Fusion | Various | Lower accuracy than data fusion in GPS study [3]. | Provides a middle ground, fusing extracted features. |

| Result Fusion | Various | Lower accuracy than data fusion in GPS study [3]. | Leverages model diversity, but decision aggregation can dilute performance. |

Beyond raw accuracy, the fusion model Lasso_D demonstrated exceptional robustness and transferability. It maintained high predictive accuracy with sample sizes as small as 200 and was resilient to variations in single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) density [3]. Furthermore, in cross-environmental prediction scenarios—a critical test for real-world application—the model showed only a 0.3% reduction in accuracy compared to predictions generated using data from the same environment [3].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Validated Comparisons

To ensure the reproducibility of fusion pipeline results, this section outlines the detailed experimental protocols and methodologies employed in the key studies cited.

The GPS Framework Experimental Protocol

The following workflow was used to generate the comparative performance data in the GPS study [3]:

Key Experimental Details:

- Datasets: Large-scale genomic and phenotypic data from four crop species (maize, soybean, rice, wheat) were used to ensure broad applicability and robustness [3].

- Model Suite: The study employed a diverse set of models for comprehensive comparison, including statistical approaches (GBLUP, BayesB), traditional machine learning (Lasso, RF, SVM, XGBoost, LightGBM), and deep learning (DNNGP) [3].

- Validation: Rigorous cross-validation techniques were applied to assess model performance, robustness to sample size and SNP density, and transferability across different environments [3].

Theoretical Selection Protocol

Beyond empirical testing, a 2025 mathematical analysis established a paradigm for selecting the optimal fusion method prior to task execution [2]. This protocol helps researchers avoid computationally expensive trial-and-error approaches.

Key Theoretical Findings and Selection Criteria:

- Equivalence Conditions: The study derived the specific mathematical conditions under which early and late fusion methods produce equivalent results within the framework of generalized linear models [2].

- Failure Conditions for Early Fusion: The analysis identified scenarios where early fusion is likely to underperform, particularly in the presence of nonlinear feature-label relationships [2].

- Critical Sample Size Threshold: A key contribution was the proposal of a critical sample size threshold at which the performance dominance of early and late fusion models reverses. This provides a quantitative guide for method selection based on dataset size [2].

- Selection Paradigm: Based on these derivations, the researchers introduced a fusion method selection paradigm that uses factors like sample size, feature quantity, and modality number to recommend the most appropriate fusion method before model training [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Solutions

Building an effective genomic-phenotypic fusion pipeline requires both physical research reagents and computational tools. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Category | Item | Specific Function in Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Data Generation | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Provides high-throughput genomic data, including SNPs and structural variants, forming one core data modality [33]. |

| Phenotypic Data Acquisition | High-Throughput Phenotyping Systems (e.g., drones, sensors) | Automated collection of large-scale phenotypic data (e.g., plant size, architecture) from field or lab conditions [33]. |

| Phenotypic Data Acquisition | ChronoRoot 2.0 Platform | An open-source tool that uses AI to track and analyze multiple plant structures, such as root architecture, over time [33]. |

| Intermediate Data Layers | Multi-Omics Technologies (Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics) | Provides intermediate molecular layers that help bridge the gap between genotype and phenotype for a more complete picture [33]. |

| Computational & AI Tools | PhenoAssistant | Employs Large Language Models (LLMs) to orchestrate phenotype extraction, visualization, and model training from complex datasets [33]. |

| Computational & AI Tools | Genomic Language Models | Treat DNA sequences as a language to predict the functional impact of genetic variants and detect regulatory elements [33]. |

| Computational & AI Tools | Explainable AI (XAI) Tools | Critical for interpreting complex fusion models, providing biological insights, and building trust in predictions by explaining the model's reasoning [33]. |

The empirical evidence and methodological frameworks presented in this guide consistently support the thesis that data fusion strategies significantly enhance predictive accuracy compared to single-technique genomic or phenotypic approaches. The integration of genomic and phenotypic data addresses the inherent complexity of biological systems, where observable traits are rarely the product of a single genetic factor.

The future of genomic-phenotypic fusion lies in more seamless and automated pipelines. Key emerging trends include the increased use of Generative AI for in-silico experimentation and data augmentation, a stronger focus on modeling temporal and spatial dynamics of traits, and the development of closed-loop systems that integrate AI-based prediction with genome editing (e.g., CRISPR) to rapidly test and validate biological hypotheses [33]. As these technologies mature, the fusion of genomic and phenotypic data will undoubtedly become a standard, indispensable practice in basic biological research and applied drug development.

Cancer survival prediction remains a pivotal challenge in precision oncology, directly influencing therapeutic decisions and patient management. Traditional prognostic models, often reliant on single data types like clinical variables or genomic markers, frequently fail to capture the complex molecular heterogeneity that drives patient-specific outcomes. The integration of multiple omics technologies—known as multi-omics fusion—has emerged as a transformative approach that leverages complementary biological information to achieve more accurate and robust predictions. This case study examines the paradigm of data fusion predictive accuracy versus single-technique research through the lens of cancer survival prediction, demonstrating how integrated analytical frameworks consistently outperform unimodal approaches across multiple cancer types and methodological implementations.

Recent technological advancements have generated vast amounts of molecular data through high-throughput sequencing and other molecular assays, creating unprecedented opportunities for comprehensive cancer profiling. Large-scale initiatives such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) provide publicly available datasets that integrate clinical, omics, and histopathology imaging data for thousands of cancer patients [34] [35]. Concurrently, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have empowered the development of sophisticated fusion models capable of managing the high dimensionality and heterogeneity of these multimodal datasets [35] [8]. This convergence of data availability and computational innovation has positioned multi-omics fusion as a cornerstone of next-generation cancer prognostic tools.

Performance Comparison: Multi-omics Fusion vs. Single-Modality Approaches

Quantitative evidence from recent studies consistently demonstrates the superior predictive performance of multimodal data integration compared to single-modality approaches. The comparative analysis reveals that fusion models achieve significant improvements in key prognostic metrics across diverse cancer types.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Fusion Strategies vs. Single Modalities in Cancer Survival Prediction

| Cancer Type | Model/Framework | Data Modalities | Fusion Strategy | Performance (C-Index) | Superiority vs. Single Modality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Multimodal Deep Learning [34] | Clinical, Somatic SNV, RNA-seq, CNV, miRNA, Histopathology | Late Fusion | Highest test-set concordance | Consistently outperformed early fusion and unimodal approaches |