Navigating the Chemical Universe of Natural Products: From Structural Diversity to Drug Discovery Applications

This comprehensive review explores the vast chemical space and structural diversity of natural products (NPs) and their critical importance in modern drug discovery.

Navigating the Chemical Universe of Natural Products: From Structural Diversity to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

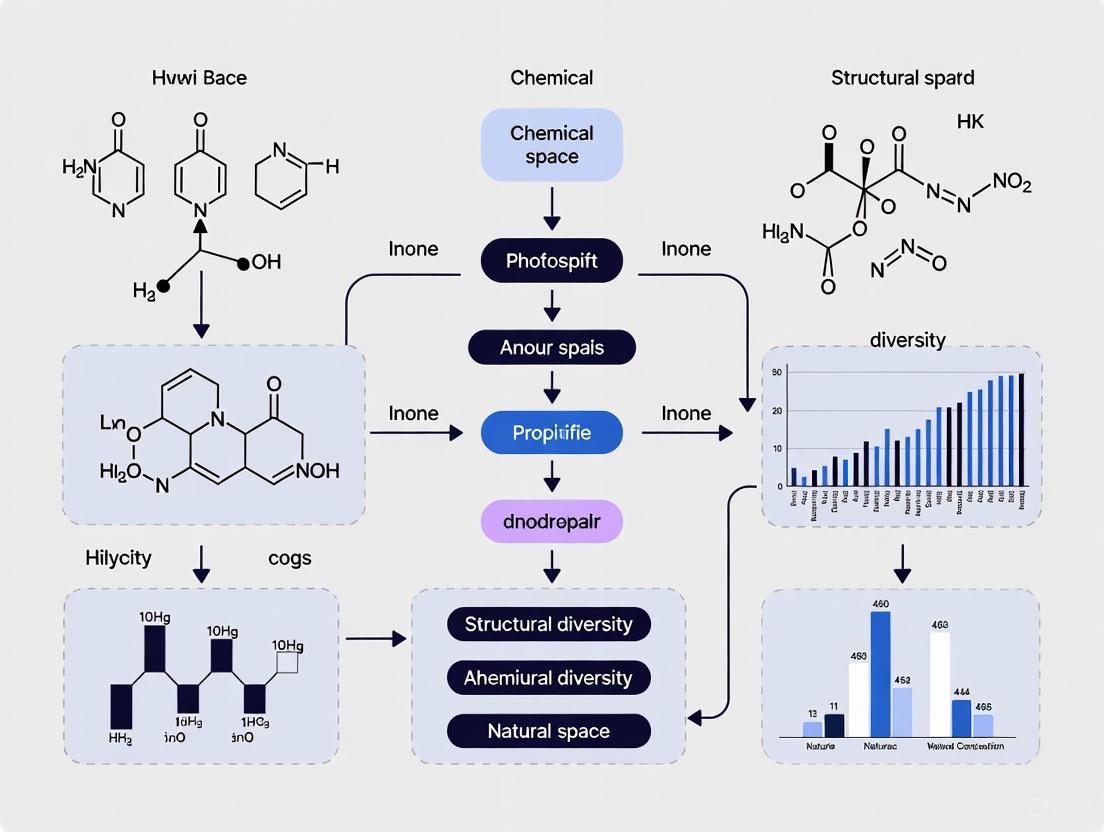

This comprehensive review explores the vast chemical space and structural diversity of natural products (NPs) and their critical importance in modern drug discovery. It examines the foundational concepts defining NP chemical space, highlighting how NPs occupy unique regions not explored by synthetic compounds while largely adhering to drug-like properties. The article details cutting-edge methodological approaches for analyzing and navigating this chemical space, including cheminformatics tools, database resources like COCONUT and NPAtlas, and computational screening techniques. Significant challenges in NP research are addressed, such as data curation, stereochemical accuracy, and material supply bottlenecks, along with optimization strategies like diversity-oriented synthesis. Finally, the review provides comparative validation of NP drug-likeness and success rates, demonstrating NPs' proven track record as sources of new pharmacological entities. This resource is designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage natural product diversity for therapeutic innovation.

Defining Natural Product Chemical Space: The Foundation of Bioactive Diversity

Chemical space is a foundational concept in cheminformatics and modern drug discovery, representing a theoretical multidimensional domain where each point corresponds to a unique chemical structure positioned according to its specific properties [1]. This conceptual framework systematically organizes molecular diversity, enabling researchers to analyze, classify, and visualize relationships within vast compound collections [1]. The chemical universe of possible small organic molecules is astronomically large, with estimates exceeding 10^60 compounds, making exhaustive exploration impractical [1]. Consequently, the field focuses on navigating and mapping biologically relevant regions of this space to identify promising drug-like molecules with desired biological activities [2].

The structural diversity of natural products plays a crucial role in populating chemical space with biologically validated starting points [3]. Natural products exhibit unique chemical diversity complementary to synthetic collections, possessing greater steric complexity and a wider variety of ring systems [3]. This diversity stems from evolutionary pressure and provides privileged scaffolds for interacting with biological targets, making natural products unsurpassed sources of leading structures in drug discovery [3]. As the drug discovery field evolves, artificial intelligence and novel computational approaches are revolutionizing how we explore and exploit chemical space, creating paradigm shifts across research and development platforms [2].

The Fundamentals of Chemical Space

Theoretical Framework and Definitions

Chemical space serves as a systematic tool to organize molecular diversity by postulating that different molecules occupy different regions of a mathematical space where each molecule's position is defined by its properties [1]. While no single unified definition exists, the core concept encompasses all compounds that could potentially exist, with spaces often constricted to specific regions depending on the included compounds and molecular representations [1]. These representations can utilize chemical descriptors (e.g., fingerprints, physicochemical, or quantum properties), biological descriptors (e.g., bioactivity, bioavailability), or clinical descriptors (e.g., side effects) [1].

The exploration of chemical space is fundamentally governed by the structure of small molecule libraries, which serve as essential collections for identifying molecules with desired biological activity [2]. These libraries can be broadly categorized into diverse libraries offering broad structural variety and focused libraries targeting specific protein families or biological pathways [2]. The generation of these libraries employs various methodologies, including combinatorial chemistry, diversity-oriented synthesis, fragment-based approaches, natural product extraction, and computational generation of virtual libraries [2].

Key Dimensions and Molecular Descriptors

The dimensions of chemical space are defined by molecular descriptors that capture critical structural and physicochemical properties. Key descriptors and filters used to navigate drug-relevant chemical space include:

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptors and Filters for Navigating Chemical Space

| Descriptor/Filter | Description | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Lipinski's Rule of 5 [2] | Molecular weight <500 Da, CLogP <5, H-bond donors ≤5, H-bond acceptors ≤10 | Predicts oral bioavailability of drug-like molecules |

| Fragment-Based "Rule of 3" [2] | Molecular weight <300 Da, CLogP ≤3, H-bond donors ≤3, H-bond acceptors ≤3 | Guides design of fragment libraries for FBDD |

| ADMET Properties [2] | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity | Optimizes pharmacokinetics and reduces toxicity |

| Synthetic Accessibility Score [2] | Score based on molecular complexity (SAS >6 indicates challenging synthesis) | Assesses synthetic feasibility of designed compounds |

| Structural Complexity [2] | Chirality, stereocenters, sp2:sp3 hybridization ratios | Measures molecular complexity and synthetic challenge |

These descriptors enable the quantitative assessment of chemical space regions most likely to yield successful drug candidates by ensuring appropriate absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion characteristics while minimizing toxicity risks [2].

Methodologies for Chemical Space Analysis

Computational Tools and Algorithms

The analysis of chemical space requires specialized computational tools capable of handling millions of compounds efficiently. Recent methodological advances address the steep computational challenges of traditional similarity indices, which scale as O(N²) when comparing N molecules [1]. Innovative approaches like the iSIM framework bypass this quadratic scaling problem by comparing all molecules simultaneously with O(N) complexity, enabling practical analysis of large libraries [1]. The iSIM Tanimoto value corresponds to the average of all distinct pairwise Tanimoto comparisons, providing a global indicator of library diversity where lower values indicate more diverse collections [1].

Clustering algorithms are equally important for dissecting chemical spaces granularly. The BitBIRCH algorithm draws inspiration from Balanced Iterative Reducing and Clustering using Hierarchies but adapts it for chemical informatics by relying on iSIM to process binary vectors using Tanimoto similarity [1]. This approach uses a tree structure to reduce comparison requirements, making it suitable for large-scale chemical space analysis [1].

Dimensionality Reduction for Chemical Space Visualization

Dimensionality reduction techniques transform high-dimensional molecular descriptor data into human-interpretable 2D or 3D chemical space maps, a process known as "chemography" [4]. These methods enable researchers to visualize complex chemical relationships and identify patterns within compound libraries.

Table 2: Dimensionality Reduction Methods for Chemical Space Visualization

| Method | Type | Key Characteristics | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis [4] | Linear | Preserves global data structure; computationally efficient | Initial exploration; when linear assumptions hold |

| t-SNE [4] | Non-linear | Excellent at preserving local neighborhoods; emphasizes clusters | Detailed analysis of specific compound classes |

| UMAP [4] | Non-linear | Balances local and global structure preservation; faster than t-SNE | General-purpose mapping of diverse compound sets |

| Generative Topographic Mapping [4] | Non-linear | Generates interpretable property "landscapes"; supports NB-compliant maps | Structure-activity relationship analysis |

Benchmarking studies highlight non-linear DR algorithms (t-SNE, UMAP) as best-performing for neighborhood preservation, though PCA remains popular and sometimes more efficient for specific tasks [4]. The choice of method should be guided by suitability for particular analysis objectives rather than seeking a universally superior approach [4].

Experimental Protocol: Chemical Space Analysis of Natural Product Derivatives

The following workflow illustrates a comprehensive approach for analyzing chemical space, particularly relevant to natural products research:

Step 1: Natural Product Extraction and Modification

- Global ethanolic extraction of plant material (e.g., Ambrosia tenuifolia) followed by partitioning with solvents of increasing polarity yields subextracts enriched in specific compound classes [3].

- Chemical engineering of extracts employs diversity-oriented synthesis strategies, such as treating sesquiterpene lactone-enriched subextracts with p-toluenesulfonic acid in toluene under reflux conditions to remodel molecular scaffolds [3].

- This complexity-to-diversity approach generates structural complexity through ring distortion reactions including expansions, contractions, fusions, cleavages, and rearrangements [3].

Step 2: Bioactivity Screening

- Bioguided fractionation follows anti-glioblastoma activity in T98G cell cultures to identify bioactive fractions convergently [3].

- Chronobiological experiments evaluate temporal susceptibility to treatments on GBM cell cultures to define optimal administration timing [3].

Step 3: Chemical Space Analysis

- Calculate molecular descriptors including Morgan fingerprints (radius 2, size 1024), MACCS keys, or ChemDist embeddings from graph neural networks [4].

- Apply dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, t-SNE, UMAP, GTM) with optimized hyperparameters based on neighborhood preservation metrics [4].

- Construct Chemical Space Networks using RDKit and NetworkX, representing compounds as nodes connected by edges based on Tanimoto similarity thresholds [5].

- Analyze network properties including clustering coefficient, degree assortativity, and modularity to identify structural relationships [5].

Chemical Space Networks: A Practical Implementation

Chemical Space Networks provide an alternative representation to coordinate-based visualizations by depicting compounds as nodes connected by edges defined by specific relationships [5]. The following diagram illustrates the CSN construction process:

Implementation Protocol:

Data Curation: Load compound datasets (e.g., from ChEMBL) into Python using Pandas DataFrames. Remove compounds missing bioactivity data, check for salts as disconnected SMILES, and merge duplicate compounds by averaging activity values [5].

Fingerprint Calculation: Generate molecular representations using RDKit. Standard choices include:

- Morgan fingerprints (circular fingerprints encoding atomic environments)

- MACCS keys (predefined structural features)

- Pattern fingerprints (structural key fingerprints) [5]

Similarity Calculation: Compute pairwise Tanimoto similarity values between all compounds. For large datasets, optimize using the iSIM framework to avoid O(N²) scaling [1].

Network Construction with Threshold: Create a network where nodes represent compounds and edges represent similarity relationships exceeding a defined threshold (typically Tanimoto ≥ 0.7-0.85 for 2D fingerprints) [5].

Visualization and Analysis:

- Visualize networks using NetworkX or Gephi, optionally replacing circle nodes with 2D structure depictions [5].

- Color nodes by property values (e.g., bioactivity, physicochemical properties) [5].

- Calculate network properties including clustering coefficient, degree assortativity, and modularity to identify structural relationships [5].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Chemical Space Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [5] | Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and similarity metrics | Open-source |

| NetworkX [5] | Network Analysis Library | Constructs and analyzes chemical space networks | Open-source |

| ChEMBL [1] | Chemical Database | Provides curated bioactivity data for drug-like molecules | Public |

| DrugBank [1] | Pharmaceutical Database | Contains information on drugs and drug targets | Public |

| PubChem [1] | Chemical Database | Offers extensive compound information and bioassays | Public |

| iSIM Framework [1] | Computational Algorithm | Enables efficient similarity calculations for large libraries | Algorithm |

| BitBIRCH [1] | Clustering Algorithm | Groups chemical structures based on molecular similarity | Algorithm |

| Natural Product Extracts [3] | Experimental Material | Provides biologically validated starting points for diversification | Laboratory preparation |

Applications in Natural Products Research

Chemical space analysis provides powerful approaches for exploring and enhancing the structural diversity of natural products. The inherent complementarity between natural and synthetic chemical spaces makes natural products invaluable starting points for drug discovery [3]. Natural products exhibit structural features distinct from synthetic compounds, including greater steric complexity, wider variety of ring systems, and different distribution of heteroatoms [3]. This diversity is biologically prevalidated through evolutionary selection, enhancing the probability of bioactivity [3].

The "complexity to diversity" paradigm has emerged as a particularly powerful approach in natural products research, wherein complex natural products undergo ring distortion reactions to generate new structures that are both complex and diverse from the original natural product and from each other [3]. This process plays a fundamental role in exploring biologically relevant chemical space by taking advantage of nature's biosynthetic machinery strengthened through chemical reactions that form new carbon-carbon bonds and modify molecular scaffolds [3]. Applications include:

- Diversity-Enhanced Extracts: Direct chemical modification of natural extracts to yield mixtures containing fragments or elements conducive to bioactivity, modifying functional groups in original natural products or their molecular skeletons [3].

- Bioguided Fractionation: Using bioactivity measurements to guide fractionation and purification convergently, enabling discovery of bioactive compounds not previously described in traditional phytochemical studies [3].

- Chemical Space Navigation: Mapping natural product derivatives into chemical space visualizations to identify regions of high bioactivity and structure-activity relationships [3].

Quantitative analysis of chemical space diversity reveals that while the number of compounds in public repositories is rapidly increasing, this growth does not automatically translate to increased chemical diversity [1]. Tools like iSIM and BitBIRCH clustering enable researchers to identify which compound additions genuinely expand chemical space versus those that merely populate existing regions [1]. This understanding is crucial for designing natural product-derived libraries that effectively explore uncharted regions of biologically relevant chemical space.

Natural products (NPs) are chemical compounds produced by living organisms—including plants, microorganisms, and marine organisms—that have served as invaluable resources for drug discovery and biomedical research. These molecules are characterized by their complex chemical structures, diverse three-dimensional architectures, and precise stereochemistry, properties that have evolved to fulfill specific biological functions. Within the broader context of chemical space—the theoretical multidimensional space encompassing all possible molecules and compounds—natural products occupy a distinct and privileged region known as the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) [6]. This region comprises molecules with biological activity, both beneficial and detrimental, making NPs particularly significant for therapeutic development [6].

The structural complexity of natural products arises from biosynthetic pathways that have been optimized through evolution, resulting in molecules with intricate scaffolds and defined spatial configurations that often underlie their biological efficacy. Approximately 30% of FDA-approved drugs from 1981 to 2019 originated from natural products or their derivatives, particularly in areas such as anti-infectives and anti-tumor therapies [7]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of the unique structural properties of natural products, with a focus on their chemical complexity, three-dimensional architecture, and stereochemical features, framed within the context of chemical space exploration and analysis.

Chemical Complexity and Scaffold Diversity

The chemical complexity of natural products manifests primarily through their intricate molecular scaffolds and diverse functional group decorations. Unlike many synthetic compounds, natural products often feature highly elaborate carbon skeletons with multiple stereocenters and complex ring systems. This complexity arises from enzyme-mediated biosynthetic pathways that facilitate chemical transformations often challenging to achieve through conventional synthetic chemistry.

Quantifying Natural Product Complexity

Analysis of microbial natural products in the Natural Products Atlas database (version v2024_09), containing 36,454 compounds, reveals distinct clustering patterns based on structural similarity [8]. When using the Morgan fingerprint method (radius 2) and Dice similarity metric (cutoff = 0.75), the database organizes into 4,148 clusters containing two or more compounds, encompassing 30,094 compounds (82.6% of the database) [8]. The median cluster size is 3, with 1,209 clusters containing at least five members [8]. This distribution demonstrates both the extensive diversity and the presence of structural families within natural product space.

Table 1: Chemical Clustering in Microbial Natural Products

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Total Compounds | 36,454 | Microbial natural products in NP Atlas [8] |

| Clusters (≥2 compounds) | 4,148 | Dice similarity ≥ 0.75 [8] |

| Clustered Compounds | 30,094 | 82.6% of total database [8] |

| Median Cluster Size | 3 | [8] |

| Large Clusters (≥5 members) | 1,209 | [8] |

| Taxonomy-Specific Clusters | 1,093 | ≥95% fungal or bacterial origin [8] |

Structural Hotspots in Chemical Space

Certain classes of natural products form particularly dense regions in chemical space, characterized by high structural similarity within the class but significant distinction from other scaffolds. Notable examples include:

- Microcystins (cluster 50): 245 compounds with median edge count of 196, indicating high interconnectivity [8]

- Peptaibols (cluster 263): Well-known compound class with high structural similarity [8]

- Anabaenopeptins (cluster 415): Distinct structural class with characteristic features [8]

These "hotspots" represent regions of chemical space where evolutionary processes have generated structural variants around privileged scaffolds, potentially reflecting optimized interactions with biological targets [8].

Three-Dimensional Architecture and Stereochemistry

The biological functions of natural products depend not only on their two-dimensional structures but crucially on their three-dimensional configurations and stereochemical properties. This section examines the precise spatial arrangements that characterize natural products and the methodologies for their study.

Stereochemical Features of Natural Products

Natural products frequently contain multiple chiral centers with defined configurations, a result of stereospecific biosynthetic enzymes. This stereochemical complexity creates a vast configurational space; for example, a natural product with 10 chiral centers theoretically has 1,024 (2¹â°) possible stereoisomers, though biosynthetic pathways typically produce single, defined configurations [9]. This precise stereochemistry is essential for biological activity, as it determines molecular recognition by biological targets.

The challenge of stereochemical characterization is significant: over 20% of known natural products lack complete chiral configuration annotations, and only 1-2% have fully resolved crystal structures [9]. This represents a substantial knowledge gap in natural product research, as incomplete stereochemical assignment hinders accurate understanding of structure-activity relationships.

Experimental and Computational Approaches to 3D Structure Determination

Experimental Structure Validation Protocols

The stereochemical quality of three-dimensional molecular structures is typically validated using standardized computational tools that assess geometrical parameters against established standards:

- MAXIT Software Analysis: Evaluates abnormal stereochemical parameters across six categories: close contacts, bond length deviations, bond angle deviations, deviation from planarity, chirality issues, and phosphate bond linkages [10]

- MolProbity Software Package: Assesses structural accuracy through Clashscore, which identifies overlapping or too-close atoms in molecular models [10]

- X3DNA-DSSR: Verifies base-pairing geometries and handedness of helices in nucleic acid structures [10]

- Barnaba: Analyzes base-pairing geometries in RNA structures [10]

Validation of RNA tertiary structures using these tools has revealed that bond angle deviations represent the most common type of geometrical inaccuracy (183 errors across 17 reference structures), followed by close contacts (54 errors across 7 structures) and bond length deviations (32 errors across 5 structures) [10].

Table 2: Stereochemical Quality Assessment of RNA 3D Structures

| Stereochemical Parameter | Structures with Errors | Total Errors | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Angle Deviations | 17 structures | 183 | MAXIT [10] |

| Close Contacts | 7 structures | 54 | MAXIT [10] |

| Bond Length Deviations | 5 structures | 32 | MAXIT [10] |

| Phosphate Bond Linkages | 7 structures | 9 | MAXIT [10] |

| Deviation from Planarity | 2 structures | 9 | MAXIT [10] |

| Chirality Issues | 0 structures | 0 | MAXIT [10] |

NatGen: Deep Learning for 3D Structure Prediction

The NatGen framework represents a significant advancement in computational prediction of natural product structures. This deep learning approach leverages structure augmentation and generative modeling to predict chiral configurations and 3D conformations with remarkable accuracy [9]. The methodology achieves:

- 96.87% accuracy in chiral configuration prediction on benchmark natural product structural datasets [9]

- 100% accuracy in a prospective study involving 17 recently resolved plant-derived natural products [9]

- Average root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of predicted 3D structures below 1Å—smaller than the radius of a single atom [9]

Using NatGen, researchers have successfully predicted the 3D structures of 684,619 natural products from COCONUT (the largest open natural product repository), significantly expanding the structural landscape of publicly available natural product data [9].

Diagram 1: NatGen 3D Structure Prediction Workflow. This diagram illustrates the deep learning framework for predicting natural product structures, from data input to validated 3D model output.

Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Analysis

The experimental study of natural product structures requires specialized reagents and computational tools. The following table details key resources used in contemporary natural products research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Natural Product Structural Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Model | In vitro prediction of intestinal permeability, transport, absorption, and bioavailability of phytochemicals [11] | Bioavailability studies of 84 phytochemicals for drug development [11] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor & alvaDesc | Computation of molecular descriptors from Isomeric SMILES representations for QSPR modeling [11] | Encoding stereochemistry, chemical structure, and properties into 40 molecular descriptors [11] |

| Natural Products Atlas | Database of published microbial natural products structures for diversity analysis and chemical space exploration [8] | Analysis of 36,454 microbial compounds using Morgan fingerprints and Dice similarity metrics [8] |

| COCONUT Database | Largest open natural product repository used for large-scale 3D structure prediction [9] | Source database for predicting 3D structures of 684,619 natural products using NatGen [9] |

| Factotum System | EPA data management platform for chemical curation, quality assurance, and controlled vocabulary assignment [12] | Curation of chemical use information and product composition data in CPDat [12] |

Structural Modification Strategies for Natural Products

Structural modification of natural products represents a crucial approach for optimizing their pharmacological properties while maintaining their biologically privileged scaffolds. This process typically addresses limitations such as unfavorable ADMET properties, low potency, limited specificity, and high toxicity [7].

Computational Approaches to Natural Product Optimization

Artificial intelligence and molecular generative models have emerged as transformative technologies for the rational structural modification of natural products. These approaches can be categorized based on their modification strategies and applicability to different research scenarios:

Target-Interaction-Driven Strategies

When the biological target of a natural product is known, structure-based design approaches leverage protein-ligand interaction data to guide modifications:

- Fragment Splicing Methods: Programs including DeepFrag, FREED, DEVELOP, STRIFE, POEM, DrugGPS, TACOGFN, PGMG, FRAME, D3FG, AUTODIFF, and MolEdit3D select fragments from predefined chemical libraries and splice them onto natural product scaffolds, considering target binding requirements [7]

- Molecular Growth Methods: Tools such as 3D-MolGNNRL, DiffDec, AutoFragDiff, PMDM, DeepICL, DiffInt, and TargetSA generate molecules directly in the 3D space of target pockets through atom-by-atom or substructure autoregressive generation or global generation based on diffusion models [7]

Molecular Activity-Data-Driven Strategies

For natural products with unknown molecular targets or when optimizing physicochemical properties:

- Group Modification Models: Focus on structural modification of characteristic regions (side chains and functional groups) to enhance biological activity and improve properties through "fine-tuning" [7]

- Scaffold Hopping Approaches: Reconstruct core scaffolds through linker design and scaffold hopping to optimize the central connected portion of molecules [7]

Diagram 2: AI-Driven Structural Modification Workflow. This diagram outlines computational strategies for natural product optimization based on target information availability.

Natural products possess unique structural properties—including complex molecular scaffolds, defined three-dimensional architectures, and precise stereochemistry—that distinguish them in chemical space and underpin their biological activities. Their position within the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) reflects evolutionary optimization for molecular recognition and biological function. Contemporary research approaches, ranging from AI-driven structure prediction to rational modification strategies, continue to reveal the structural sophistication of natural products while providing methodologies to overcome challenges associated with their development as therapeutic agents. The integration of computational structural prediction with experimental validation represents a promising frontier for expanding our understanding and utilization of natural product diversity in drug discovery and chemical biology.

The concept of "chemical space" is a core theoretical construct in cheminformatics, representing a multidimensional space where the position of each molecule is defined by its structural and physicochemical properties [6] [1]. Within this vast universe, two major families of compounds, natural products (NPs) and synthetic compounds (SCs), occupy distinct and characteristic regions. Understanding the differences in how these compounds occupy chemical space is not merely an academic exercise; it is fundamental to guiding drug discovery and the design of novel bioactive molecules [13] [14].

Natural products, forged by billions of years of natural selection, are essential reservoirs for innovative drug discovery, with a significant proportion of approved small-molecule drugs being directly or indirectly derived from them [13] [14]. Conversely, synthetic compounds, born from human ingenuity in the laboratory, offer access to vast regions of chemical space not explored by nature. However, a critical and often overlooked question is the extent to which the structural characteristics of NPs have historically influenced the evolution of SCs [13]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth, time-dependent comparison of the structural variations and chemical space occupation of NPs versus SCs, framing the analysis within the context of a broader thesis on the structural diversity of natural products research. By integrating recent chemoinformatic analyses, we delineate the evolving landscapes of these compound classes, offering a strategic perspective for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to navigate the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) for future discoveries [13] [6].

Methodological Framework for Chemical Space Analysis

A rigorous, time-dependent chemoinformatic analysis requires standardized protocols for data curation, descriptor calculation, and diversity assessment. The following methodologies underpin the key findings discussed in subsequent sections.

Data Curation and Time-Series Grouping

To enable a chronological comparison, large datasets of NPs and SCs must be sorted and grouped. One robust approach involves the following steps:

- Data Sources: NPs are typically sourced from curated databases such as the Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP) or the Collection of Open Natural Products (COCONUT). SCs can be compiled from multiple synthetic compound databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) [13] [15].

- Temporal Ordering: Molecules are sorted in early-to-late order based on their CAS Registry Numbers, which serve as a proxy for their discovery or publication date [13].

- Grouping Strategy: The sorted molecules are divided into sequential groups, each containing a fixed number of compounds (e.g., 5,000 molecules per group). The remaining molecules after equal grouping are excluded from the analysis to maintain consistency [13].

Calculation of Molecular Descriptors and Fragments

A comprehensive set of descriptors is calculated to characterize the physicochemical and structural properties of the compounds.

- Physicochemical Properties: Key descriptors include molecular weight, molecular volume, molecular surface area, number of heavy atoms, number of bonds, and calculated logP (a measure of hydrophobicity) [13].

- Ring System Analysis: The number of rings, ring assemblies, aromatic rings, and non-aromatic rings are computed for each molecule. The analysis is extended to include ring sizes (e.g., 4-, 5-, 6-membered) and glycosylation patterns for NPs [13].

- Molecular Fragmentation: Molecules are decomposed into fundamental structural units using several methods:

- Bemis-Murcko Scaffolds: These represent the core ring systems and linkers of a molecule, defining its central framework [13].

- RECAP Fragments: The Retrosynthetic Combinatorial Analysis Procedure (RECAP) generates fragments based on chemically sensible and synthetically accessible bonds [13].

- Side Chains: The substituents attached to the core scaffolds are analyzed separately to understand decoration patterns [13].

Assessment of Diversity and Chemical Space

The diversity of compound libraries and their occupation of chemical space are quantified using several advanced algorithms.

- Intrinsic Similarity (iSIM) Framework: This tool efficiently quantifies the internal diversity of a library by calculating the average of all distinct pairwise Tanimoto similarities between molecular fingerprints within the set. Its O(N) computational complexity allows it to handle very large libraries. A lower iSIM Tanimoto (iT) value indicates a more diverse collection [1].

- Complementary Similarity: This concept identifies central (medoid-like) and outlier molecules within a set. Removing a central molecule significantly decreases the set's diversity, while removing an outlier has little effect. This helps map the internal structure of the chemical space [1].

- BitBIRCH Clustering: An efficient clustering algorithm for binary fingerprints, BitBIRCH uses a tree structure to group molecules based on Tanimoto similarity, enabling a "granular" view of the formation and evolution of clusters within chemical space over time [1].

- Chemical Space Visualization: Techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Tree MAP (TMAP), and SAR Map are employed to project high-dimensional descriptor data into two or three dimensions for visual interpretation of the distribution and overlap of NPs and SCs [13].

Evaluation of Biological Relevance

The biological relevance of a compound or a library can be inferred from its presence in databases annotated with bioactivity data, such as ChEMBL [6]. The premise is that molecules with known biological activities occupy the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS). The enrichment of generated fragments or scaffolds in these bioactive databases can serve as a metric for their potential biological relevance [6] [15].

Comparative Analysis of Structural and Physicochemical Properties

Applying the aforementioned methodologies reveals profound and systematic differences between NPs and SCs, which have evolved over time.

Molecular Size and Complexity

Table 1: Time-Dependent Trends in Molecular Size Descriptors

| Property | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Consistent increase over time; recently discovered NPs are larger [13]. | Variation within a limited range, constrained by synthesis technology and drug-like rules (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) [13]. |

| Heavy Atoms | Number of heavy atoms shows a consistent increase [13]. | Number of heavy atoms varies within a constrained range [13]. |

| Molecular Volume/Surface Area | Mean values exhibit a consistent increase [13]. | Average values vary within a limited range [13]. |

| Number of Rings | Average number gradually increases over time [13]. | Evident rise in the mean number of rings and ring assemblies [13]. |

| Aromatic vs. Aliphatic Rings | Most rings are non-aromatic. The number of aromatic rings changes little over time [13]. | Distinguished by a greater prevalence of aromatic rings, due to the widespread use of compounds like benzene in synthesis [13]. |

| Ring Assemblies | NPs have more rings but fewer ring assemblies, indicating the presence of bigger fused rings (e.g., bridged rings, spiral rings) [13]. | The increase in ring assemblies suggests more complex, linked ring systems [13]. |

| Glycosylation | Glycosylation ratios and the mean number of sugar rings in each glycoside increase gradually over time [13]. | Not a common feature in typical SC libraries. |

The data clearly indicate that NPs are generally larger and more complex than SCs, a trend that has become more pronounced over time. This is attributed to technological advancements in the isolation and characterization of larger NPs. SCs, in contrast, have their size bounded by synthetic feasibility and the historical influence of "drug-like" rules [13].

Ring Systems and Scaffolds

The analysis of ring systems provides deep insight into the structural foundations of these compound classes.

- NPs Prefer Complex, Saturated Systems: NPs contain a higher proportion of non-aromatic rings and larger, fused ring systems (as evidenced by fewer ring assemblies). This points to a structural landscape rich in aliphatic and stereochemically complex scaffolds [13] [13].

- SCs Favor Aromatic and Simple Rings: SCs are characterized by a greater involvement of aromatic rings, particularly stable five- and six-membered rings. A notable trend is the sharp increase in four-membered rings in SCs after 2009, likely driven by a desire to enhance pharmacokinetic properties [13].

Fragmentation and Functional Groups

Deconstructing molecules into their core scaffolds and side chains reveals divergent evolutionary paths.

Table 2: Key Differences in Molecular Fragments and Substituents

| Fragment Component | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Scaffolds | Larger, more diverse, and more complex ring systems [13] [13]. Contain more aliphatic rings and fewer heteroatoms (except oxygen) [13]. | Contain more heteroatoms (N, S) and phenyl rings. Scaffolds are generally less complex and more synthetically accessible [13] [16]. |

| Side Chains/Substituents | Have more oxygen atoms, stereocenters, and very few heteroatoms other than oxygen. Exhibit higher structural complexity [13] [14]. | Rich in nitrogen and sulfur atoms, halogens, and aromatic rings. Generally have lower structural complexity [13] [14]. |

| Functional Groups | Feature more oxygen atoms, ethylene-derived groups, and unsaturated systems [13] [17]. | Feature more nitrogen atoms. Functional groups are generally chemically easily accessible [13] [17]. |

The fragment analysis underscores that NPs and SCs are built from fundamentally different chemical "vocabularies." NPs are rich in oxygen-based functionality and complex, saturated architectures, while SCs are rich in nitrogen, aromatics, and halogens, reflecting the synthetic chemist's toolkit [13] [17] [14].

Occupation and Evolution of Chemical Space

The distinct structural features of NPs and SCs translate into unique patterns of chemical space occupation.

Diversity and Uniqueness

- Structural Diversity: NPs consistently cover a more diverse chemical space than SCs. The iSIM framework analysis of library releases shows that merely increasing the number of SCs does not automatically translate to increased chemical diversity [1]. The intrinsic diversity of NP libraries often remains higher.

- Uniqueness of Space: The chemical space of NPs has become less concentrated and more unique over time. Recently discovered NPs increasingly occupy regions of chemical space that are sparsely populated by SCs [13]. Conversely, the chemical space of SCs, while broad, is more densely concentrated and homogeneous in comparison.

Temporal Evolution of Chemical Space

A time-dependent analysis reveals divergent evolutionary trajectories:

- NPs: The NP chemical space has been expanding outward, with newer compounds becoming larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic. This expansion is driven by the discovery of structurally novel compounds that push the boundaries of known chemical space [13].

- SCs: The evolution of SCs has been heavily influenced by the pursuit of "drug-likeness." While SCs have undergone a continuous shift in physicochemical properties, these changes are constrained within a defined range governed by rules like Lipinski's Rule of Five [13]. Although SCs possess a broader range of synthetic pathways and the potential for immense structural diversity, their evolution has not fully mirrored the direction of NPs. There has been a noted decline in the biological relevance of SCs over time, suggesting that sheer numbers do not guarantee coverage of BioReCS [13] [1].

Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS)

The biologically relevant chemical space is the subset of the chemical universe containing molecules with biological activity [6]. NPs, by virtue of their co-evolution with biological targets, are inherently enriched in BioReCS. It is estimated that 68% of approved small-molecule drugs between 1981 and 2019 were directly or indirectly derived from NPs [13]. This highlights that the NP chemical subspace is a privileged region for identifying bioactive leads. While SC libraries can be enormous, their coverage of BioReCS is often less efficient, a phenomenon that contributes to high attrition rates in high-throughput screening campaigns focused purely on synthetic libraries [13] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Chemical Space Analysis

| Item/Tool | Function/Brief Explanation | Relevance to NPs vs. SCs |

|---|---|---|

| Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP) | A curated database of natural product structures used as a primary source for NP data [13]. | Essential for obtaining standardized and reliable NP structures for comparative analysis. |

| ChEMBL / PubChem | Large, public databases of bioactive molecules and synthetic compounds with extensive bioactivity annotations [6] [1]. | Serve as primary sources for SC data and bioactivity data to define BioReCS. |

| RDKit / CACTVS Toolkit | Open-source and commercial cheminformatics toolkits for calculating molecular descriptors, generating fingerprints, and processing chemical structures [13] [16]. | Fundamental for descriptor calculation, structure standardization, and fragment generation. |

| iSIM Framework | A computational tool for efficiently calculating the intrinsic similarity (diversity) of large compound libraries with O(N) complexity [1]. | Crucial for quantifying and comparing the internal diversity of massive NP and SC libraries. |

| BitBIRCH Algorithm | An efficient clustering algorithm for binary fingerprints that enables the grouping of millions of molecules [1]. | Allows for a granular analysis of the cluster formation and evolution in NP and SC chemical spaces over time. |

| RECAP Fragmentation | A method to generate molecular fragments based on chemically sensible retrosynthetic rules [13]. | Used to decompose NPs and SCs into comparable, chemically meaningful fragments for diversity analysis. |

| Bemis-Murcko Scaffolds | An algorithm to extract the core ring system and linker of a molecule, ignoring side chains [13]. | Enables comparison of the central scaffolds of NPs and SCs, highlighting differences in core complexity. |

| LHASA Transform Rules | A set of rules originally developed for retrosynthetic analysis, encoding robust chemical reactions [16]. | Used to generate synthetically accessible virtual inventories (SAVI) and define the synthetic feasibility of chemical space regions. |

| Tetraphenylstibonium bromide | Tetraphenylstibonium Bromide|510.1 g/mol|CAS 16894-69-2 | Tetraphenylstibonium Bromide is an organoantimony reagent for research. It is a pentavalent stibonium salt. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Colistin | Colistin | Colistin is a last-resort antibiotic for researching multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The comprehensive, time-dependent analysis confirms that natural products and synthetic compounds occupy distinct and evolving regions of the chemical universe. NPs continue to be a source of unprecedented structural complexity and diversity, densely populating the biologically relevant chemical space due to their evolutionary history. SCs, while vast in number and accessible through synthesis, have not fully evolved toward the structural profiles of NPs, remaining constrained by drug-like paradigms and synthetic practicality [13].

This divergence presents both a challenge and an opportunity for drug discovery. The challenge lies in the inefficient coverage of BioReCS by conventional SC libraries. The opportunity, however, is to leverage the unique attributes of NPs to guide the design of next-generation synthetic libraries. Strategies such as designing pseudo-natural products (pseudo-NPs) by combining NP fragments in novel arrangements represent a human-driven branch of chemical evolution that inherits the biological relevance of NPs while exploring new chemical territory [13] [18]. Furthermore, the application of generative artificial intelligence (AI) models for the structural modification of NPs is a transformative approach. These models can be trained to generate novel, NP-inspired structures that optimize desired properties while maintaining synthetic accessibility, effectively bridging the gap between the NP and SC chemical subspaces [18].

In conclusion, the future of productive drug discovery lies not in choosing between natural products and synthetic compounds, but in intelligently integrating them. By understanding their complementary strengths—the biological relevance and complexity of NPs, and the vast synthetic accessibility and tunability of SCs—researchers can more effectively navigate and populate the chemical universe to discover the life-saving therapeutics of tomorrow.

The concept of "chemical space" provides a powerful framework for understanding the relationship between molecular structure and biological activity in drug discovery. This multidimensional space, where molecular properties define coordinates and relationships between compounds, contains a specialized region known as the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS), which encompasses molecules with biological activity—both beneficial and detrimental [6]. Natural products (NPs) represent a uniquely privileged region within BioReCS, having evolved over millions of years to interact with biological systems through evolutionary refinement [19]. Unlike synthetic compound libraries designed primarily around synthetic accessibility and compliance with simplified rules, NPs originate from biological necessity, functioning as defense chemicals, signaling agents, and ecological mediators fine-tuned for optimal interactions with living systems [19].

The drug-likeness paradigm has historically been dominated by rule-based approaches such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, which established molecular guidelines for oral bioavailability. However, NPs consistently challenge these conventions, demonstrating that molecular complexity and structural diversity can confer superior biological targeting despite deviations from traditional drug-like properties [19]. This apparent paradox—how NPs balance structural complexity with favorable pharmacological properties—stems from their unique position within chemical space and their evolutionary optimization for biological interfaces, offering valuable lessons for modern drug discovery.

Structural and Physicochemical Characteristics of Natural Products

Defining Features in Chemical Space

Natural products occupy a distinct region of chemical space characterized by structural properties that differ significantly from those of synthetic compounds (SCs). When analyzed through chemoinformatic approaches, NPs exhibit several distinguishing characteristics that contribute to their biological relevance and drug-likeness:

Table 1: Key Structural Differences Between Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds

| Characteristic | Natural Products | Synthetic Compounds | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular complexity | Higher proportions of sp³-hybridized carbon atoms, increased stereochemical complexity [19] | More planar structures, lower sp³ character | Enhanced 3D shape complementarity with biological targets |

| Oxygen content | Higher oxygenation [19] | Lower oxygen content | Improved hydrogen bonding capacity |

| Nitrogen content | Lower nitrogen content [19] | Higher nitrogen content | Different target recognition patterns |

| Aromatic rings | Fewer aromatic rings [13] | Predominance of aromatic rings, especially benzene derivatives | Reduced planarity, better solubility |

| Ring systems | Larger fused rings (bridged rings, spiral rings) [13] | More five- and six-membered rings | Structural rigidity and defined 3D geometry |

| Molecular weight | Generally larger [13] | Constrained by synthetic and drug-like rules | Broader interaction surface with targets |

Property Distributions and Drug-Likeness

Analysis of property distributions reveals that NPs often fall outside the traditional "drug-like" space defined by synthetic compounds yet demonstrate favorable bioavailability. This apparent contradiction can be explained by their structural biosynthesis and evolutionary optimization. While synthetic compounds are typically designed with strict adherence to rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, NPs frequently violate these guidelines yet maintain excellent pharmacological profiles [19]. For instance, many NP-based drugs exhibit exceptional oral bioavailability despite non-compliance with traditional rules, as evidenced by the increasing average molecular weight of newly approved oral medications [19].

Time-dependent analyses of NPs and SCs reveal divergent evolutionary trajectories in chemical space. NPs have progressively become larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic over time, exhibiting increased structural diversity and uniqueness [13]. Conversely, SCs have undergone continuous shifts in physicochemical properties constrained within a defined range governed by drug-like constraints, resulting in a decline in biological relevance despite broader synthetic diversity [13].

The Chemical Space Perspective: Why Natural Products Succeed

Privileged Positioning in BioReCS

The biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) comprises molecules with biological activity, both beneficial and detrimental [6]. Natural products occupy a privileged position within BioReCS due to their evolutionary history and biological origins. Several factors contribute to this advantageous positioning:

Evolutionary Optimization: NPs have evolved through natural selection to interact specifically with biological macromolecules, leading to inherent bio-compatibility and target affinity [19]. This evolutionary refinement provides NPs with mechanisms of action that exploit biological vulnerabilities, particularly in pathogens and cancer cells [19].

Structural Complementarity: The elevated molecular complexity of NPs, including higher sp³ character and increased stereochemical complexity, enables superior three-dimensional binding with protein targets compared to the more planar structures typical of synthetic libraries [19].

Polypharmacology Potential: The structural complexity of NPs facilitates simultaneous interactions with multiple biological targets, making them particularly valuable for treating complex diseases through network modulation rather than single-target inhibition [20].

Multi-Target Engagement and Network Pharmacology

Complex diseases often involve intricate molecular networks that are difficult to modulate with single-target drugs. Natural products offer inherent advantages in this context due to their multi-target capabilities [20]. The "single target, single disease" model has shown limitations in clinical practice, often resulting in insufficient therapeutic effects, adverse side effects, and drug resistance [20]. NPs naturally address these challenges through their ability to simultaneously regulate multiple targets within disease network systems, affecting overall physiological balance and potentially improving efficacy while reducing toxicity and resistance [20].

This multi-target engagement represents a fundamental aspect of the drug-likeness paradigm for NPs, where balanced polypharmacology compensates for deviations from traditional drug-like rules. Rather than maximizing affinity for a single target, NPs typically exhibit moderate affinity for multiple targets, creating a more holistic therapeutic effect particularly valuable for complex, multifactorial diseases [20].

Figure 1: Relationship between natural products, synthetic compounds, and specialized regions within the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS)

Experimental Approaches for Natural Product Drug Discovery

Advanced Screening and Characterization Technologies

Modern NP drug discovery employs sophisticated technologies that address historical limitations while leveraging the unique advantages of natural product chemistry:

Table 2: Key Methodologies in Natural Product Drug Discovery

| Methodology | Technical Approach | Application in NP Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | High-resolution separation coupled with mass detection | Metabolome profiling, chemical feature identification, and dereplication [21] |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Automated screening of compound libraries against biological targets | Identification of bioactive NPs from large collections [20] [19] |

| Genome Mining | Bioinformatics analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) | Prediction of NP diversity and prioritization of strains for chemical investigation [19] |

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) | Machine learning and generative models for pattern recognition | NP structural modification, property prediction, and activity optimization [18] |

| Quantitative In Vitro to In Vivo Extrapolation (QIVIVE) | Mathematical modeling to translate in vitro activity to in vivo doses | Prediction of human pharmacokinetics and efficacious doses [22] |

Quantitative Library Design and Metabolomics

Rational design of NP screening libraries has been revolutionized by quantitative approaches that maximize chemical diversity while minimizing redundancy. The integration of genetic barcoding with metabolomics profiling enables researchers to build NP libraries with predetermined levels of chemical coverage [21]. This approach allows for the identification of overlooked pockets of chemical diversity within taxa, refocusing collection strategies toward underexplored regions of chemical space.

Studies on fungal isolates have demonstrated that a surprisingly modest number of isolates (195 isolates) can capture nearly 99% of chemical features within a dataset [21]. However, the observation that 17.9% of chemical features appeared in single isolates suggests that fungi continuously explore nature's metabolic landscape, presenting both challenges and opportunities for library design [21]. This quantitative framework enables evidence-based decisions about sampling depth and resource allocation in NP discovery programs.

Computational and Modeling Approaches

AI and Generative Models for Natural Product Optimization

Artificial intelligence has emerged as a transformative technology for NP-based drug discovery, particularly in the structural modification of natural products for improved drug-likeness. AI-driven approaches address several key challenges in NP optimization:

Target-Guided Optimization: When target structures are known, generative models can propose structural modifications that maintain or enhance binding affinity while improving pharmacokinetic properties [18].

Phenotype-Based Optimization: For systems where molecular targets remain unidentified, AI models can learn structure-activity relationships from phenotypic screening data to guide optimization [18].

Chemical Space Navigation: AI algorithms can efficiently explore the chemical space around promising NP scaffolds, identifying structural variations that balance complexity with favorable properties [18].

These approaches leverage the privileged positioning of NPs in BioReCS while addressing potential limitations such as poor solubility or metabolic instability through targeted structural modifications.

Read-Across and RASAR Modeling

The Read-Across Structure-Activity Relationship (RASAR) methodology represents an innovative approach that combines elements of quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling with similarity-based read-across predictions [23]. This hybrid approach is particularly valuable for NP research where experimental data may be limited. RASAR modeling incorporates similarity-based descriptors and error-based descriptors into a machine learning framework, using similarity-based information from close structural neighbors to predict properties of query compounds [23].

This approach has demonstrated superior predictive performance compared to conventional QSAR models, particularly for complex endpoints like hepatotoxicity [23]. For NP research, RASAR modeling offers a powerful tool for predicting ADMET properties while navigating the complex chemical space occupied by natural products.

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for natural product drug discovery combining traditional and modern technologies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Drug Discovery

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Public database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties [6] | Comparison of NP properties with known bioactive compounds |

| PubChem Database | Public repository of chemical substances and their biological activities [6] | Chemical space analysis and activity prediction |

| Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) | Mass spectrometry data sharing and annotation platform [14] | NP identification and dereplication |

| AntiSMASH | Bioinformatics platform for identifying biosynthetic gene clusters [19] | Genome mining for novel NP discovery |

| InertDB | Database of curated inactive compounds [6] | Definition of non-biologically relevant chemical space |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Patient-derived cell models for phenotypic screening [19] | Biologically relevant screening for NP activity |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Gene editing technology for target validation [19] | Mechanism of action studies for NPs |

| Acefylline Piperazine | Acefylline Piperazinate|CAS 18833-13-1|RUO | Acefylline piperazinate is a xanthine derivative for research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. |

| 4-[(E)-2-nitroprop-1-enyl]phenol | 4-[(E)-2-Nitroprop-1-enyl]phenol | 4-[(E)-2-Nitroprop-1-enyl]phenol is a high-purity phenolic research chemical. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Natural products present a compelling paradox within the drug-likeness paradigm: they frequently violate conventional rules of drug-likeness while demonstrating exceptional pharmacological success. This apparent contradiction resolves when viewed through the lens of chemical space and evolutionary optimization. NPs occupy a privileged region within the biologically relevant chemical space, shaped by millions of years of evolutionary refinement for biological interfaces [19].

The structural complexity of NPs—including higher sp³ character, increased stereochemical complexity, and diverse ring systems—provides superior three-dimensional complementarity with biological targets compared to synthetic compounds [19] [13]. This structural advantage, combined with inherent multi-target engagement capabilities, positions NPs as ideal starting points for addressing complex diseases requiring systems-level modulation [20].

Modern approaches to NP-based drug discovery leverage advanced technologies including genomics, AI, and sophisticated modeling to navigate the complex relationship between molecular structure and biological activity. By understanding and respecting the unique positioning of NPs within chemical space, researchers can more effectively harness nature's chemical ingenuity for therapeutic innovation. The future of NP-inspired drug discovery lies in integrated approaches that combine traditional knowledge with modern technologies, guided by a deeper understanding of the fundamental principles that govern bio-relevance in chemical space.

Natural products (NPs) represent an invaluable resource for drug discovery and development, with an estimated 80% of all clinically used antibiotics originating from natural compounds [24]. The exploration of natural product chemical space—the multi-dimensional descriptor-based domain encompassing all possible natural compounds—is crucial for identifying novel bioactive molecules. However, the experimental characterization of natural products remains resource-intensive, with only approximately 400,000 fully characterized natural products known to date [24]. This limitation has accelerated the development of comprehensive databases that catalog known natural products and enable in-silico exploration of their structural diversity.

Within the context of natural products research, structural diversity refers to the variety of molecular scaffolds, functional groups, and physicochemical properties represented across different natural product collections. Understanding this diversity is essential for drug development professionals seeking to identify novel therapeutic candidates or explore structure-activity relationships. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of three major natural product databases—COCONUT, NPAtlas, and SuperNatural II—as essential exploratory tools for mapping the chemical space of natural products, complete with experimental methodologies and visualization frameworks for researchers in the field.

Comparative Analysis of Major Natural Product Databases

The landscape of natural product databases has expanded significantly, with resources ranging from comprehensive global collections to specialized focused databases. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the three primary databases examined in this guide:

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Major Natural Product Databases

| Database | Content Size | Update Frequency | Accessibility | License | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COCONUT | >400,000 compounds [24] | Regular updates (2024 version available) [25] | Freely accessible without restrictions [25] | Creative Commons CC0 [25] | Integrated NP-likeness scoring, structural diversity analysis, user submissions [25] [26] |

| NPAtlas | 32,552 microbial compounds [27] | 2021 version (most recent) [27] | Open access [27] | Not specified | Specialized in microbial natural products, taxonomic origins, chemical ontology terms [27] |

| SuperNatural II | ~326,000 molecules [28] | 2022 update (version 3.0) [28] | Freely available without registration [28] | Not specified | Predicted toxicity, vendor information, mechanism of action, taste prediction [28] |

Each database offers distinct advantages for researchers exploring chemical space. COCONUT provides the most extensive collection with comprehensive annotation, while NPAtlas offers specialized coverage of microbial natural products, and SuperNatural II includes valuable predictive data on toxicity and biological activity. The selection of an appropriate database depends on the specific research objectives, whether focused on broad chemical space exploration or targeted investigation of particular natural product classes.

Database-Specific Architectures and Functional Capabilities

COCONUT (COlleCtion of Open Natural prodUcTs)

COCONUT represents one of the most comprehensive open natural product databases, launched in 2021 and regularly updated since [25] [29]. The database architecture incorporates not only chemical structures but also extensive metadata including names and synonyms, source organisms and specific plant parts, geographical collection data, and literature references [26]. The platform enables multiple search modalities including textual queries, exact structure matching, substructure search, and chemical similarity analysis, providing researchers with flexible tools for chemical space exploration [26].

A key innovation in COCONUT 2.0 is the implementation of community curation features and user data submissions, enhancing the database's comprehensiveness and accuracy through collaborative scientific effort [26]. The database also provides specialized analytical tools including fragment analysis using the Ertl algorithm for functional group identification, scaffold generation for core structure analysis, and calculated properties including NP-likeness scores, synthetic accessibility scores, and QED drug-likeness metrics [25]. These features enable researchers to quantitatively assess the position of compounds within the broader chemical space of natural products.

NPAtlas (The Natural Products Atlas)

NPAtlas specializes in microbially-derived natural products, providing detailed coverage of bacterial and fungal metabolites [27]. The database incorporates full taxonomic descriptions of source microorganisms and employs dual chemical ontology systems (NP Classifier and ClassyFire) for standardized structural classification [27]. This specialized focus makes NPAtlas particularly valuable for researchers investigating microbial chemical ecology or seeking novel antibiotics and other bioactive compounds from microbial sources.

The NPAtlas platform features a comprehensive application programming interface (API) that supports programmatic access and integration with other bioinformatics resources [27]. The database is explicitly developed following FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), ensuring optimal utility for computational natural products research [27]. Integration with complementary resources including the Minimum Information About a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (MIBiG) repository and the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform enables multi-omics approaches to natural product discovery [27].

SuperNatural II

SuperNatural II provides extensive coverage of natural products and natural product-based derivatives, with particular emphasis on drug discovery applications [28]. The database includes predictive data on biological activity, including target-specific predictions for antiviral, antibacterial, antimalarial, and anticancer applications, as well as central nervous system (CNS) target potential [28]. This functional annotation makes it particularly valuable for drug development professionals seeking to identify lead compounds for specific therapeutic areas.

A distinctive feature of SuperNatural II is its incorporation of taste prediction using VirtualTaste models, expanding its utility beyond pharmaceutical applications to include food and sensory sciences [28]. The database also includes vendor information for many compounds, facilitating the acquisition of physical samples for experimental validation [28]. The platform supports multiple search strategies including template-based similarity searching, compound name queries, substructure searches, and physical property filters, enabling efficient navigation of its extensive chemical space [28].

Experimental Protocols for Database Utilization

Protocol 1: Chemical Space Mapping Using Molecular Descriptors

Purpose: To quantitatively map and visualize the chemical space covered by natural product databases to assess structural diversity and identify regions of interest for targeted screening.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Download canonical SMILES representations of natural products from target databases. For COCONUT, bulk download is available in SDF, CSV, or database dump formats [26].

- Structure Standardization: Process structures using standardization tools such as RDKit or MolVS to ensure consistent representation, including neutralization, desalting, and canonical tautomer generation [30].

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute key molecular descriptors using cheminformatics toolkits (e.g., RDKit):

- Molecular weight (MW)

- Partition coefficient (Wildman-Crippen LogP)

- Hydrogen bond acceptors/donors (HBA/HBD)

- Topological polar surface area (TPSA)

- Fraction of carbon sp³ atoms (FCSP³)

- Number of rotatable bonds [24]

- Chemical Space Visualization: Apply dimensionality reduction techniques such as t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) to project high-dimensional descriptor data into two-dimensional space for visualization [24].

- Cluster Analysis: Identify dense regions and outliers in the chemical space mapping to guide targeted exploration efforts.

Figure 1: Workflow for Chemical Space Mapping and Analysis

Protocol 2: Scaffold Analysis for Structural Diversity Assessment

Purpose: To identify and quantify molecular scaffolds within natural product databases to assess structural diversity and scaffold representation across different biological sources.

Methodology:

- Scaffold Extraction: Generate molecular scaffolds according to the Bemis-Murcko method, which involves systematic removal of side chains to reveal core structural frameworks [30].

- Scaffold Classification: Categorize scaffolds based on structural properties (e.g., ring systems, connectivity) using tools such as RDKit or specialized scaffold generators.

- Frequency Analysis: Quantify scaffold occurrence to identify prevalent structural motifs within and across databases.

- Diversity Metrics: Calculate scaffold diversity metrics including scaffold uniqueness rates and scaffold-hitting compounds to quantify structural diversity [25].

- Comparative Analysis: Compare scaffold distributions across different natural product databases or between natural products and synthetic compound libraries.

Figure 2: Scaffold Diversity Analysis Workflow

Protocol 3: Virtual Screening for Natural Product Discovery

Purpose: To employ natural product databases for in-silico screening against biological targets to identify potential lead compounds with desired bioactivity.

Methodology:

- Library Preparation: Curate and filter natural product databases based on drug-likeness criteria (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five, synthetic accessibility scores) [25].

- Target Preparation: Obtain three-dimensional structures of biological targets (e.g., from Protein Data Bank) and prepare for docking (add hydrogens, assign charges).

- Molecular Docking: Perform high-throughput docking of natural product libraries against biological targets using software such as AutoDock Vina or Schrödinger Glide.

- Score Interpretation: Analyze docking scores and binding interactions to identify promising natural product hits.

- Hit Prioritization: Prioritize hits based on multiple criteria including docking scores, chemical novelty, structural diversity, and synthetic accessibility [25].

Advanced Applications in Chemical Space Exploration

Expanding Natural Product Chemical Space with AI-Generated Libraries

Recent advances in deep generative modeling have enabled significant expansion of explorable natural product chemical space. As demonstrated by a 2023 study, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) trained on known natural products from COCONUT can generate over 67 million natural product-like structures—a 165-fold expansion beyond known natural products [24]. This approach dramatically increases the accessible chemical space for virtual screening campaigns while maintaining natural product-like characteristics.

The generated structures exhibit NP Score distributions closely resembling known natural products (Kullback-Leibler divergence of 0.064 nats), confirming their natural product-like character [24]. Furthermore, t-SNE visualization of molecular descriptor space shows that these AI-generated libraries cover significantly expanded physicochemical space while maintaining dense coverage in regions occupied by known natural products, suggesting their utility for exploring novel yet biologically relevant chemical space [24].

Cross-Database Chemical Space Integration

Integrating multiple natural product databases enables more comprehensive mapping of natural product chemical space. The Latin American Natural Product Database (LaNAPDB) initiative represents one such effort, combining regional databases from multiple countries including Argentina (NaturAr), Brazil (NuBBEDB, SistematX, UEFS), Panama (CIFPMA), Peru (PeruNPDB), and Mexico (BIOFACQUIM, UNIIQUIM) [30]. Similar integration approaches can be applied to the major global databases discussed in this guide, creating a unified chemical space map for natural products.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for natural product database research and chemical space exploration:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Products Chemical Space Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Natural Products Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit [30] | Structure standardization, molecular descriptor calculation, scaffold analysis [24] |

| NPClassifier | Deep learning-based natural product classification [24] | Biosynthetic pathway annotation and structural classification [24] |

| NP Score | Natural product-likeness quantification [24] | Bayesian measure of similarity to natural product structural space [24] |

| MolVS | Molecule validation and standardization [30] | Structure normalization for comparative analysis [30] |

| ChEMBL Curation Pipeline | Chemical structure curation [24] | Structure sanitization and standardization following FDA/IUPAC guidelines [24] |

COCONUT, NPAtlas, and SuperNatural II provide complementary platforms for exploring the chemical space and structural diversity of natural products. COCONUT offers the most extensive collection with advanced analytical capabilities, NPAtlas provides specialized coverage of microbial metabolites, and SuperNatural II incorporates valuable predictive data for drug discovery applications. Together, these databases enable comprehensive mapping of natural product chemical space, facilitating the identification of novel bioactive compounds and expanding our understanding of nature's structural diversity. The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks presented in this guide provide researchers with standardized methodologies for leveraging these resources in natural product discovery and development efforts.

Tools and Techniques for Mapping and Exploiting NP Chemical Diversity

The exploration of chemical space is a fundamental objective in natural product-based drug discovery. Chemical space can be conceptualized as a multidimensional universe where molecular properties define coordinates and relationships between compounds [6]. Within this vast universe, the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) comprises molecules with biological activity, a region where natural products (NPs) have historically played a paramount role [31] [6]. It has been estimated that from the drugs approved between 1981 and 2019, 3.8% are unaltered natural products, while 18.9% are natural product derivatives [31].

Natural products present unique cheminformatic challenges due to their distinct structural characteristics. Compared to typical synthetic, drug-like compounds, NPs often exhibit a wider range of molecular weight, contain multiple stereocenters, and possess a higher fraction of sp³-hybridized carbons [32]. This structural complexity, while contributing to their biological potency and selectivity, makes the encoding of natural products via traditional molecular representations particularly challenging [32] [33]. This technical guide comprehensively explores the key cheminformatics methodologies—molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and scaffold analysis—employed to navigate and characterize the complex chemical space of natural products, thereby facilitating modern drug discovery efforts.

Molecular Descriptors and Fingerprints for Natural Products

Defining the Chemical Space of Natural Products

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations derived from molecular structure that serve as the fundamental metrics for quantifying chemical space [34]. Profiling natural product datasets typically involves a core set of physicochemical properties that capture size, polarity, and flexibility: Molecular Weight (MW), the octanol/water partition coefficient (SlogP), Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA), counts of Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) and Acceptors (HBA), and the number of Rotatable Bonds (RB) [31]. These descriptors help contextualize NPs within the broader drug-like chemical space and are essential for understanding their absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADME/Tox) profiles [31].

Molecular Fingerprints: Encoding Structure for Computation

Molecular fingerprints convert molecular structures into fixed-length vectors, enabling computational processing and similarity assessment [32]. They are crucial for quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and virtual screening [32]. The performance of different fingerprinting algorithms varies significantly when applied to natural products due to their unique structural motifs [32] [33].

Table 1: Major Categories of Molecular Fingerprints and Their Application to Natural Products

| Fingerprint Category | Description | Examples | Performance on NPs |

|---|---|---|---|