Navigating Nature's Pharmacy: Charting the Natural Product Chemical Space for Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic exploration of natural product (NP) chemical space to uncover novel therapeutic leads.

Navigating Nature's Pharmacy: Charting the Natural Product Chemical Space for Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic exploration of natural product (NP) chemical space to uncover novel therapeutic leads. It covers the foundational concept of the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS), where NPs occupy unique and underexplored regions compared to synthetic libraries. The piece details cutting-edge methodological approaches, including AI-driven screening, genomics, and high-throughput assays, and addresses significant challenges such as supply, characterization, and regulatory hurdles. By validating the success of NPs through approved drugs and comparative analyses, the article underscores NPs' irreplaceable role in addressing unmet medical needs, particularly in antimicrobial and anticancer therapy, and outlines a future roadmap for integration with innovative technologies.

Defining the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space: Why Natural Products Are Unique

The concept of chemical space (CS), also referred to as the "chemical universe," is a foundational concept in modern drug discovery and many other chemical disciplines [1]. While often used intuitively, chemical space is formally defined as a multidimensional space where molecular properties—both structural and functional—define coordinates and relationships between compounds [1]. Within this vast universe, the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS) comprises the subset of molecules with biological activity, spanning both beneficial compounds (therapeutics) and detrimental ones (toxins) [1].

The exploration of chemical space is particularly crucial for drug discovery, as the theoretical number of possible small organic molecules below 500 Da is estimated to exceed 10^60 structures [2]. This immense size makes comprehensive experimental screening impossible, necessitating intelligent navigation strategies to identify promising regions for bioactive molecule discovery, especially those inspired by or derived from natural products [3].

Defining the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS)

Conceptual Framework of BioReCS

BioReCS encompasses all molecules that interact with biological systems, creating a complex landscape of chemical subspaces (ChemSpas) distinguished by shared structural or functional features [1]. This space includes not only drug-like molecules but also agrochemicals, flavor and odor chemicals, food components, and natural products [1]. A critical aspect of BioReCS is that it includes compounds with both desirable and undesirable biological effects, including promiscuous binders, poly-active molecules, and toxic compounds [1].

Systematic study of BioReCS requires molecular descriptors that define the dimensionality of the space, with the choice of descriptors depending on project goals, compound classes, and dataset characteristics [1]. The rise of machine learning has further driven the development of novel molecular representations that can efficiently navigate these complex spaces [1].

Key Databases for BioReCS Exploration

Chemical compound databases serve as essential resources for exploring BioReCS. The table below summarizes major public databases covering different regions of the biologically relevant chemical space.

Table 1: Representative Public Compound Databases Covering Different Regions of BioReCS

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [1] | Bioactive small molecules, primarily organic compounds | Major source for poly-active and promiscuous structures; drug discovery |

| PubChem [1] | Bioactive small molecules with extensive annotations | Biological activity analysis; chemical biology research |

| InertDB [1] | Curated and AI-generated inactive compounds | Defining non-biologically relevant chemical space; negative data for machine learning |

| Dark Chemical Matter [1] | Compounds repeatedly inactive in HTS assays | Understanding chemical features associated with lack of bioactivity |

Mapped and Underexplored Regions of BioReCS

The exploration of BioReCS has been uneven, with certain regions receiving extensive attention while others remain largely uncharted:

- Heavily Explored Regions: The chemical space of drug-like small organic molecules and natural products has been extensively characterized [1]. Related areas such as small peptides and other beyond Rule of 5 (bRo5) entities are also reasonably well-mapped [1].

- Underexplored Regions: Several chemically and biologically important classes remain underrepresented, including metal-containing molecules (often filtered out by standard cheminformatics tools), large natural products, macrocycles, protein-protein interaction (PPI) modulators, PROTACs, and mid-sized peptides [1]. Many of these fall into the bRo5 category and present unique modeling challenges [1].

- Dark Regions: BioReCS also includes "gray-to-dark" areas containing compounds with undesirable biological effects, such as toxic chemicals [1]. These regions have received less attention but are vital for understanding what separates harmful from beneficial compounds.

Chemical Space Exploration Strategies for Drug Discovery

Navigating Chemical Space with Computational Tools

The vastness of chemical space necessitates sophisticated computational approaches for efficient navigation. Several algorithmic strategies have been developed to handle trillion-sized compound collections:

Table 2: Key Algorithmic Approaches for Chemical Space Exploration

| Algorithm | Search Principle | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| FTrees [4] | Fuzzy pharmacophore similarity | Identifying close analogs with similar pharmacophore properties |

| SpaceLight [4] | Molecular fingerprint similarity (ECFP/CSFP) | High-throughput similarity screening using Tanimoto metrics |

| SpaceMACS [4] | Maximum common substructure (MCS) | Scaffold-based similarity searching and analysis |

These algorithms enable researchers to identify close neighbors of known bioactive compounds within massive virtual chemical spaces. For example, screening FDA-approved drugs against the eXplore chemical space (containing 2.8 trillion virtual molecules) demonstrated that these methods can retrieve high-similarity analogs for a significant percentage of known drugs, providing starting points for drug optimization campaigns [4].

Natural Product-Informed Exploration

Natural products represent a privileged region of BioReCS, having evolved through biological selection processes to interact with macromolecular targets [3]. Strategies for natural product-informed exploration of chemical space include:

- Structural simplification: Creating simplified analogs of complex natural products while retaining core bioactive elements [3].

- Biology-inspired synthesis: Using natural product biosynthetic pathways as inspiration for synthetic library design [3].

- Chemical space mapping: Positioning natural products within broader chemical space to identify underrepresented structural regions [3].

These approaches have enabled the discovery of novel bioactive molecules that might not have been identified through traditional screening methods, providing access to distinctive regions of BioReCS [3].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Universal Descriptors for Cross-Chemical Space Analysis

The structural diversity across BioReCS presents challenges for consistent chemical space analysis using traditional descriptors optimized for specific compound classes [1]. Ongoing efforts aim to develop universal molecular descriptors that can accommodate diverse chemical types:

- Molecular quantum numbers: Provide a unified framework for molecular representation [1].

- MAP4 fingerprint: Designed to accommodate entities ranging from small molecules to biomolecules and metabolomic data [1].

- Neural network embeddings: Derived from chemical language models, these show promise in encoding chemically meaningful representations [1].

Workflow for Chemical Space Exploration in Drug Discovery

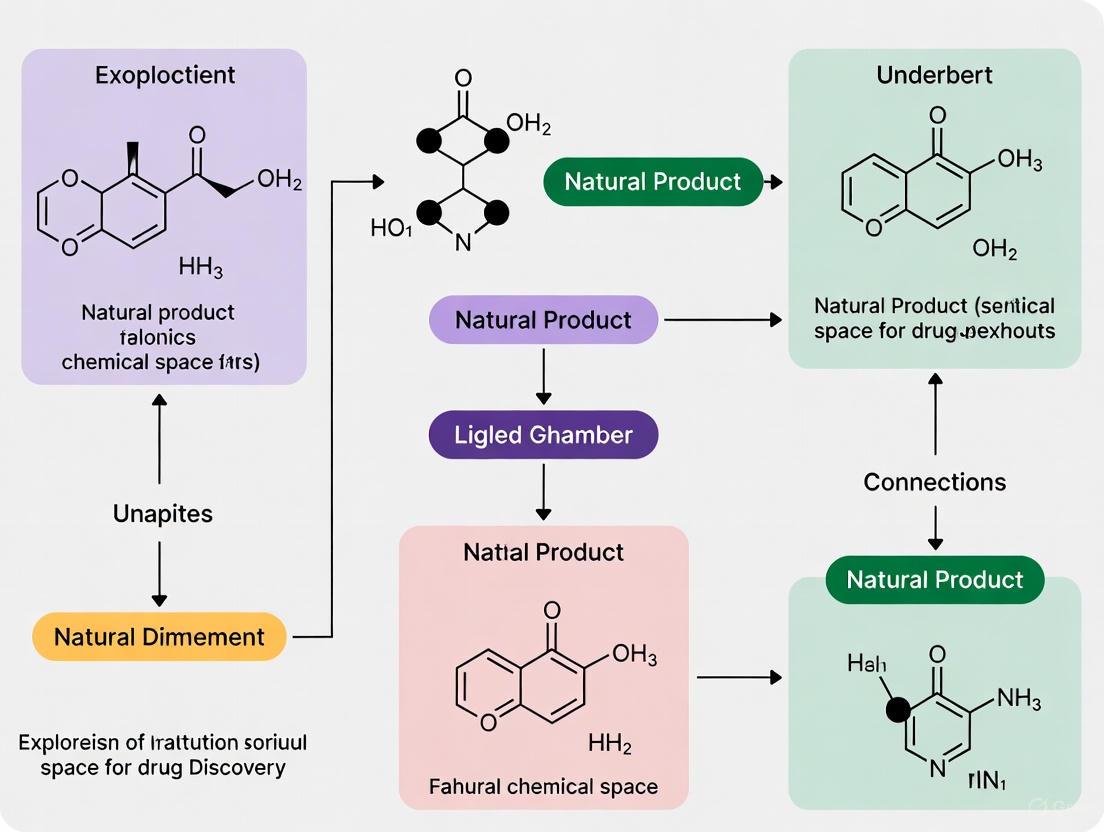

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for exploring chemical space in drug discovery, particularly emphasizing natural product-inspired approaches:

Figure 1: Workflow for Natural Product-Informed Drug Discovery

Addressing pH-Dependent Chemical Space

A critical consideration in BioReCS exploration is the pH-dependent nature of many bioactive compounds [1]. Most chemoinformatics analyses assume neutral charge states, yet approximately 80% of contemporary drugs are ionizable under physiological conditions [1]. This ionization significantly impacts solubility, permeability, absorption, distribution, toxicity, and target binding, necessitating methods that account for charged species in chemical space analysis [1].

Visualization and Analysis of Chemical Space

Dimensionality Reduction for Chemical Space Mapping

The high-dimensional nature of chemical space requires dimensionality reduction techniques for visualization and interpretation [1]. Common approaches include:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Projects chemical space into lower dimensions based on variance maximization [2].

- Self-Organizing Maps (SOMs): Neural network-based approach for producing low-dimensional representations [2].

- t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE): Particularly effective for visualizing high-dimensional data in two or three dimensions [5].

- UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection): Preserves more of the global structure compared to t-SNE [5].

These visualization approaches enable researchers to identify clusters of compounds with similar properties, locate sparsely populated regions of chemical space that may represent opportunities for novel discovery, and understand the relationship between natural products and synthetic compounds [5] [2].

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Chemical Space Exploration

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in BioReCS Exploration |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, ZINC, GDB [1] [2] | Source of annotated chemical structures and bioactivity data |

| Similarity Search Tools | FTrees, SpaceLight, SpaceMACS [4] | Identify analogs and nearby compounds in chemical space |

| Molecular Descriptors | ECFP, MAP4, Molecular Quantum Numbers [1] | Numeric representations encoding chemical structure |

| Visualization Platforms | Chemical cartography tools, SOM implementations [5] | 2D/3D projection of high-dimensional chemical space |

| Virtual Screening | Docking, Pharmacophore screening [6] | Computational prioritization of compounds for testing |

Applications in Natural Product-Based Drug Discovery

Integrating Multi-Omics Data with Chemical Space Analysis

Modern drug discovery increasingly leverages network-based multi-omics integration to understand complex biological systems and their interaction with chemical space [7]. These approaches combine various molecular data types (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) with biological networks (protein-protein interaction, drug-target interaction) to better predict drug responses, identify novel targets, and facilitate drug repurposing [7].

For natural product research, this means positioning natural compounds within broader biological context networks, connecting their chemical structures to target networks, metabolic pathways, and phenotypic effects [7]. Method categories include:

- Network propagation/diffusion models

- Similarity-based integration approaches

- Graph neural networks

- Network inference models [7]

Case Study: Natural Product-Inspired Discovery

Research has demonstrated that natural product-informed exploration of chemical space enables the discovery of distinctive and novel bioactive small molecules [3]. These approaches help focus molecular discovery on biologically relevant regions of chemical space, increasing the likelihood of identifying useful chemical probes and therapeutic candidates [3].

The relationship between natural products, chemical space exploration, and drug discovery can be visualized as follows:

Figure 2: Natural Product-Informed BioReCS Exploration

Future Directions and Challenges

The exploration of BioReCS faces several important challenges and opportunities:

- Descriptor Development: There remains a pressing need for systematic molecular fingerprints that can handle biomaterials, inorganic molecules, and other underexplored compound classes [1].

- Standardization Tools: Initiatives like the proposed ChemSpace Tool for non-targeted analysis aim to standardize the reporting of chemical space coverage and improve method comparability [8] [9].

- Integration of Dark Matter: More comprehensive inclusion of negative data (inactive compounds) and poorly characterized regions will refine the boundaries of BioReCS [1].

- Temporal and Spatial Dynamics: Future methods may incorporate the dynamic nature of biological systems and their interaction with chemical space [7].

As these challenges are addressed, the systematic exploration of biologically relevant chemical space, particularly regions inspired by natural products, will continue to drive innovation in drug discovery and chemical biology.

Natural products (NPs) from plants, animals, and microorganisms have served as a cornerstone of pharmacotherapy throughout human history, providing a rich source of structurally diverse and biologically active compounds for treating human diseases [10] [11]. These secondary metabolites represent an invaluable chemical resource, with over half of approved small-molecule drugs originating directly or indirectly from natural product scaffolds [12] [10]. The structural complexity and evolutionary optimization of natural products for biological interaction make them exceptionally suited for drug discovery, particularly for challenging targets such as protein-protein interactions [1] [12].

Within the framework of exploring natural product chemical space for drug discovery research, this review examines the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) of natural products, which encompasses molecules with both beneficial and detrimental biological activities [1]. Current databases document over 1.1 million natural products that display high structural diversity and complexity, frequently featuring glycosylation and halogenation patterns that distinguish them from synthetic compounds [12]. Despite a declining discovery rate of novel structures, natural products continue to offer unique scaffolds that occupy broader chemical spaces than synthetic compounds, positioning them as an indispensable resource for addressing current therapeutic challenges [12] [10].

Historical Foundations and Contemporary Significance

Historical Context and Industrial Perspectives

The relationship between natural products and human medicine dates back to ancient healing traditions, with well-documented use in Ayurvedic medicine, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Japanese Kampo, and European phytotherapy [10]. These traditional systems provided the initial framework for exploring nature's pharmacopeia, with many modern drugs tracing their origins to ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological knowledge [11].

The pharmaceutical industry's engagement with natural products has experienced significant fluctuations over recent decades. The 1990s witnessed a "Green Rush" in natural product research, driven by advancements in high-throughput screening (HTS) and isolation technologies that enabled systematic exploration of biodiversity [11]. This period saw substantial investment in bioprospecting initiatives targeting terrestrial and marine organisms for novel drug leads. However, in the early 2000s, most major pharmaceutical companies terminated or significantly reduced their HTS and natural product discovery programs in favor of combinatorial chemistry and rational drug design approaches [11].

Contemporary analysis reveals that the relatively low productivity of purely synthetic approaches has quietly repositioned pharmacognosy back into the drug discovery mainstream [11]. Current estimates indicate that approximately 50% of FDA-approved medications between 1981–2006 were natural products or synthetic derivatives inspired by natural products, highlighting their enduring impact despite fluctuating industrial interest [13]. This reemergence recognizes that natural products offer structural complexity and biological relevance that remains challenging to replicate through purely synthetic approaches [12] [11].

Quantitative Impact of Natural Products in Modern Therapeutics

Table 1: Therapeutic Areas Significantly Influenced by Natural Product-Derived Drugs

| Therapeutic Area | Representative Drugs | Natural Source | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Paclitaxel, Docetaxel, Trabectedin | Pacific Yew Tree, European Yew, Marine Tunicate | Taxanes represent cornerstone therapies for various cancers; marine-derived agents offer novel mechanisms |

| Infectious Diseases | Penicillins, Tetracyclines, Erythromycin | Fungi, Soil Bacteria | Foundation of anti-infective therapies with diverse mechanisms against pathogens |

| Immunosuppression | Cyclosporine, Fingolimod | Soil Fungus, Fungus Isaria sinclairii | Revolutionized organ transplantation; advanced multiple sclerosis treatment |

| Neurological Disorders | Galantamine, Huperzine A | Daffodil bulbs, Chinese Herb Huperzia serrata | Acetylcholinesterase inhibition for Alzheimer's management |

Table 2: Structural and Property Comparisons Between Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds

| Property | Natural Products | Synthetic Compounds | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Complexity | High (multiple chiral centers, intricate ring systems) | Moderate to Low | Enhanced target selectivity and novel binding modes |

| Molecular Weight | Broader distribution, including bRo5 space | Typically focused on lower MW | Access to challenging target classes like PPIs |

| Oxygen Atoms | Higher count | Lower count | Improved hydrogen bonding capacity |

| Stereochemical Complexity | High | Variable to Low | Biological specificity and metabolic stability |

| Chemical Space Coverage | Broader, underexplored regions | Narrower, focused on drug-like space | Access to novel bioactive scaffolds |

Analysis of natural product chemical space reveals distinct structural characteristics that contribute to their biological success. Natural products frequently exhibit higher stereochemical complexity, greater abundance of oxygen atoms, and more varied ring systems compared to synthetic compounds [12]. These properties enable natural products to interact with complex biological targets through unique binding modes often inaccessible to synthetic libraries [1] [12]. Marine natural products, for instance, demonstrate particularly novel scaffolds with potent bioactivities, exemplified by the development of trabectedin from a marine tunicate [11].

Exploring Natural Product Chemical Space

Chemoinformatic Characterization of Natural Product Diversity

Systematic exploration of natural product chemical space requires robust chemoinformatic approaches to characterize structural diversity, bioactivity patterns, and source-related characteristics. Natural products exhibit distinct chemical features based on their biological origins, with marine-derived compounds generally displaying higher molecular weight and hydrophobicity compared to terrestrial counterparts [12]. NPs from extreme environments such as deep-sea ecosystems and extremophiles frequently reveal novel scaffolds with unique bioactivities, highlighting the value of biodiversity exploration in drug discovery [12].

The concept of the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) provides a framework for understanding natural products' privileged status in therapeutic development. BioReCS encompasses all molecules with biological activity—both beneficial and detrimental—spanning drug discovery, agrochemistry, sensory chemistry, and toxicological domains [1]. Within this framework, natural products occupy regions characterized by high structural diversity and complexity, often distinct from synthetic compounds [1] [12].

Key chemoinformatic analyses have revealed that natural products contain a higher prevalence of unique ring systems with different atom compositions and connectivity compared to synthetic molecules [12]. This structural novelty translates to diverse biological interactions and mechanisms of action. Furthermore, natural products frequently undergo specific biochemical modifications such as glycosylation and halogenation that enhance their biological activities and target affinity [12].

Underexplored Regions of Natural Product Chemical Space

Despite extensive research, significant regions of natural product chemical space remain underexplored, presenting opportunities for future discovery. Several compound classes are notably underrepresented in current databases and drug discovery efforts:

- Metal-containing molecules: Often excluded during standard data curation due to optimization of chemoinformatics tools for small organic compounds [1]

- Macrocycles (compounds containing rings of ≥12 atoms): Complex structures with potential for modulating challenging target classes [1]

- Protein-protein interaction (PPI) modulators: Larger molecular frameworks capable of disrupting complex protein interfaces [1]

- Beyond Rule of 5 (bRo5) compounds: Natural products frequently violate traditional drug-like filters while maintaining bioavailability [1] [12]

These structurally complex natural products often fall into the beyond Rule of 5 (bRo5) category, presenting challenges for synthesis and optimization but offering unique opportunities for addressing difficult therapeutic targets [1]. Recent studies have begun systematically characterizing these underrepresented regions, including peptides, agrochemicals, metallodrugs, macrocycles, and PPI modulators [1].

Methodological Framework for Natural Product-Based Drug Discovery

Experimental Workflows and Isolation Strategies

The systematic investigation of natural products for drug discovery follows established experimental workflows that integrate traditional knowledge with modern analytical techniques. The process typically begins with source selection guided by ethnobotanical knowledge, ecological considerations, or biodiversity surveys, followed by careful specimen collection and authentication [10] [11].

Table 3: Key Methodologies in Natural Product Isolation and Characterization

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Applications in NP Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction & Fractionation | Bioassay-guided fractionation, Solvent-solvent partitioning, Liquid-liquid chromatography | Selective enrichment of bioactive compounds from complex mixtures |

| Compound Isolation | High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), Countercurrent chromatography, Flash chromatography | Purification of individual natural products from crude extracts |

| Structure Elucidation | NMR spectroscopy (1D/2D), Mass spectrometry (MS), X-ray crystallography | Determination of molecular structure and stereochemistry |

| Bioactivity Screening | High-throughput screening (HTS), Phenotypic assays, Target-based assays | Identification of biologically active natural products |

Bioassay-guided fractionation represents a cornerstone approach, wherein biological activity tracking directs the isolation of active constituents from complex natural extracts [13]. This method ensures that purification efforts focus on compounds with relevant biological effects, increasing the efficiency of lead identification. Advances in analytical technologies, particularly NMR and mass spectrometry, have dramatically accelerated the structure elucidation process, enabling determination of complex structures with minimal material [13] [11].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational approach for natural product-based drug discovery:

Computational and Artificial Intelligence Approaches

The integration of computational methods has transformed natural product research, enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space and prediction of bioactivity. Computer-aided drug design (CADD) approaches, particularly artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), have demonstrated significant utility in navigating the complex chemical space of natural products [13].

AI-driven approaches include:

- Virtual screening of natural product libraries against protein targets

- De novo design of natural product-inspired compounds

- ADMET prediction for early assessment of drug-like properties

- Structural classification and dereplication to identify novel scaffolds

Machine learning algorithms, including support vector machines (SVMs), neural networks, and decision trees, enable pattern recognition in complex structure-activity relationship data [13]. Deep learning approaches, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), facilitate analysis of molecular structures and prediction of bioactive conformations [13]. Natural language processing (NLP) techniques further enhance these approaches by extracting relevant information from scientific literature, patents, and natural product databases [13].

The following diagram illustrates the integration of AI technologies in natural product drug discovery:

Lead Identification and Optimization Strategies

From Hit to Lead: Experimental Protocols

The transition from initial bioactive natural product hits to viable lead compounds requires systematic approaches to evaluate and optimize chemical structures. Lead identification begins with validating biological activity through dose-response experiments and specificity assessments, followed by comprehensive characterization of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties [14].

High-throughput screening (HTS) and ultra-high-throughput screening (UHTS) methodologies enable efficient evaluation of extensive natural product libraries, with capacity reaching up to 100,000 assays per day using automated robotic systems [14]. These approaches offer significant advantages over traditional screening methods, including enhanced automation, reduced sample volumes, improved sensitivity, and cost savings in reagents and culture media [14].

Hit validation involves rigorous assessment of:

- Potency (IC50, EC50 values)

- Selectivity against related targets

- Cytotoxicity and general cellular toxicity

- Chemical stability under assay conditions

- Solubility and aggregation potential

Confirmed hits progress to lead optimization, where medicinal chemistry strategies enhance desirable properties while mitigating limitations. The lead optimization phase involves synthesis and characterization of analog structures, evaluation using biochemical assays (e.g., Irwin's test for neurobehavioral assessment, Ames test for genotoxicity), and detailed analysis of drug-induced metabolism through metabolic profiling [14].

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) and Analog Design

Structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies form the foundation of natural product optimization, systematically exploring how structural modifications influence biological activity and drug-like properties. SAR analysis identifies critical pharmacophoric elements—the specific molecular features essential for biological activity—and guides strategic modifications to enhance efficacy and reduce toxicity [15].

Key strategies in natural product analog design include:

- Direct chemical manipulation: Adding, removing, or swapping functional groups; making isosteric replacements; adjusting ring systems [14]

- Scaffold simplification: Reducing structural complexity while retaining essential pharmacophoric elements [15]

- Bioisosteric replacement: Substituting functional groups with alternatives that maintain biological properties but improve pharmacokinetics [15]

- Fragment-based design: Deconstructing complex natural products into simpler fragments that retain key features [15]

The iterative process of analog design and optimization follows a cyclical approach of design, synthesis, testing, and refinement. This process continues until compounds achieve the optimal balance of potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties required for preclinical development [15].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in NP Research |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Standards | Certified reference materials, Deuterated solvents, Quantitative NMR standards | Compound identification, quantification, method validation |

| Bioassay Kits | Enzyme inhibition assays, Cell viability assays, Receptor binding assays | Biological activity assessment, mechanism elucidation |

| Chromatography Materials | HPLC columns, Solid-phase extraction cartridges, Countercurrent chromatography solvents | Compound separation, purification, and enrichment |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Protein expression systems, Enzyme substrates, Reporter gene assays | Target identification and validation, mechanism studies |

| Computational Tools | Molecular docking software, QSAR programs, Cheminformatics platforms | Virtual screening, property prediction, SAR analysis |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Technological Innovations and Paradigm Shifts

The field of natural product drug discovery is experiencing significant transformation through the integration of emerging technologies and interdisciplinary approaches. Several key trends are shaping the future of this field:

Artificial Intelligence and Cheminformatics: AI-driven approaches are revolutionizing natural product research through enhanced pattern recognition in complex chemical and biological data [13]. Chemical language models and neural network embeddings generate chemically meaningful representations that can reconstruct molecular structures or predict properties, accelerating the identification of promising bioactive molecules [1]. The development of universal molecular descriptors, such as molecular quantum numbers and the MAP4 fingerprint, enables more consistent analysis of natural product chemical space across diverse compound classes [1].

Integration of Multi-Omics Technologies: Genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic approaches provide unprecedented insights into biosynthetic pathways and ecological functions of natural products [10]. These technologies facilitate the identification of gene clusters responsible for natural product biosynthesis, enabling heterologous expression and engineering of novel analogs [12].

Exploration of Underexplored Biodiversity: Research continues to focus on extreme environments (deep-sea, deserts, polar regions) and symbiotic relationships (endophytic fungi, microbial symbionts) as sources of novel natural products with unique scaffolds and bioactivities [12]. These ecosystems offer chemical diversity distinct from traditional sources, with marine natural products particularly promising for anticancer and antiviral applications [13].

Addressing Current Challenges and Limitations

Despite promising advances, natural product drug discovery faces several persistent challenges that require innovative solutions:

Supply and Sustainability Issues: Many natural products occur in minute quantities in their source organisms, creating supply challenges for development and large-scale production [13]. Sustainable sourcing strategies, including cultivation, partial synthesis, and biotechnology approaches, are essential for addressing ecological concerns and ensuring consistent supply [11].

Technical Complexities in Characterization: The structural complexity of natural products presents challenges for synthesis, structural elucidation, and optimization [13]. Advances in synthetic methodologies, analytical technologies, and computational prediction are gradually overcoming these barriers, making complex natural products more accessible for drug discovery [15].

Data Integration and Quality: The lack of standardized data quality and reporting in natural product research hampers data mining and reproducibility [10]. Initiatives to improve data curation, implement standardized protocols, and develop integrated databases are critical for advancing the field [1] [12].

The historical legacy of natural products as a pillar of pharmacotherapy continues to evolve through the integration of traditional knowledge with contemporary scientific approaches. As technological innovations provide new tools for exploring natural product chemical space, the unique structural features and biological relevance of natural products ensure their continued importance in addressing current and future therapeutic challenges. By leveraging advances in AI, omics technologies, and synthetic biology, researchers can unlock the full potential of nature's chemical diversity for the development of next-generation therapeutics.

Natural products (NPs) and their derivatives have historically been a cornerstone of pharmacotherapy, accounting for over 60% of all small-molecule drugs approved between 1981 and 2014 [16] [17]. Despite this proven utility, synthetic compounds (SCs) dominate most commercial screening libraries, constrained by decade-old conventions like Lipinski's Rule of Five and synthetic accessibility [16]. This preference persists even as challenging biological targets—such as protein-protein interactions, nucleic acid complexes, and antibacterial modalities—often remain recalcitrant to libraries of drug-like molecules [18].

The fundamental advantage of NPs lies in their evolutionary origin. As products of natural selection, they have co-evolved to interact with biological macromolecules, encoding inherent biological relevance and an ability to explore a broader swath of biologically relevant chemical space [19] [20]. Consequently, NPs exhibit structural features—such as increased molecular complexity, higher fractions of sp³-hybridized carbons, and greater stereochemical density—that are often underrepresented in synthetic libraries [18] [16]. This manuscript demonstrates how Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a powerful computational tool to visualize and quantify this superior diversity, providing a compelling rationale for reintegrating NPs into modern drug discovery pipelines.

Theoretical Foundations of Chemical Space Visualization

Defining Chemical Space and the Chemical Multiverse

In chemoinformatics, chemical space is defined as a multi-dimensional descriptor space where each molecule is represented by a numerical vector encoding aspects of its structure or physicochemical properties [21]. The concept of a chemical multiverse acknowledges that the chemical space of a single dataset is not unique; it is a "group of multiple chemical spaces, each defined by a given set of descriptors" [21]. The visual representation of this space, therefore, depends critically on the chosen descriptors and dimensionality reduction techniques.

Principal Component Analysis as a Dimensionality Reduction Tool

PCA is a mathematical method for dimensionality reduction that transforms a multidimensional dataset into a new set of orthogonal axes called principal components (PCs) [22]. These components are linear combinations of the original descriptors, with the first PC (PC1) capturing the maximum variance in the data, the second PC (PC2) capturing the next highest variance, and so on [22]. By projecting high-dimensional data onto a two- or three-dimensional plot, PCA allows for intuitive visualization of similarities, differences, and patterns within compound collections with minimal loss of information [22]. When applied to collections of NPs and SCs, PCA vividly reveals the distinct regions these classes occupy and their relative diversity.

Comparative Analysis of Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds

Time-Dependent Evolution of Structural Properties

A comprehensive, time-dependent chemoinformatic analysis comparing NPs from the Dictionary of Natural Products with SCs from 12 databases reveals distinct evolutionary trajectories. NPs discovered over time have become larger, more complex, and more hydrophobic [19]. Specifically, descriptors of molecular size—including molecular weight, molecular volume, and the number of heavy atoms—show a consistent upward trend in NPs, a phenomenon attributed to advances in separation and purification technologies [19].

Conversely, the physicochemical properties of SCs have been constrained within a narrower range, largely governed by drug-like rules and synthetic accessibility [19]. Table 1 summarizes key differentiating properties based on analyses of hundreds of thousands of compounds [19] [16].

Table 1: Key Physicochemical and Structural Differences Between Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds

| Property | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Generally larger; size increasing over time [19] | Smaller; constrained by drug-like rules [19] |

| Fraction of sp³ Carbons (Fsp3) | Higher, indicating more 3D character [16] | Lower, indicating more flat, aromatic structures [18] |

| Stereochemical Complexity | Higher number of stereocenters [19] [16] | Fewer stereocenters [18] |

| Ring Systems | More rings, larger fused rings, more non-aromatic rings [19] | More aromatic rings (e.g., benzene derivatives) [19] |

| Oxygen & Nitrogen Content | More oxygen atoms [19] | More nitrogen atoms [19] |

| Biological Relevance | High, due to evolutionary selection [19] [20] | Broader synthetic pathways but declining relevance [19] |

Visualizing Diversity with PCA and TMAP

A PCA analysis utilizing 16 two-dimensional structural descriptors on a combined ~390,000 NPs and SCs clearly demonstrates the greater structural variability of NPs [16]. The NPs occupy a broader, more dispersed region in the PCA plot, particularly evident in properties like the fraction of sp³ carbon atoms (Fsp3), a key metric of molecular complexity [16].

Another powerful visualization tool is the Tree MAP (TMAP), a two-dimensional tree-based clustering algorithm built for large-scale data. When clusters are generated using molecular fingerprints (MHFP), NPs occupy vast structural areas that are largely unexplored by synthetic molecules [16]. The TMAP visualization further corroborates that NPs are structurally more complex, not only in Fsp3 but also in features like the number of spiroatoms [16].

Experimental Protocol for Chemical Space Analysis

This section provides a detailed methodology for reproducing the chemical space comparisons described in this review.

Data Collection and Curation

1. Source Natural Product Databases:

- UNPD (Universal Natural Products Database): Available as CSV format [16].

- TCM Database@Taiwan: Available as MOL2 file [16].

- NP Atlas: Available as CSV for download [16].

- FooDB: A public database containing food chemicals and their flavors [21].

2. Source Synthetic Compound Database:

- ZINC Database: A popular resource for commercially available compounds. Use the "ZINC in-stock" subset for readily available synthetic molecules [16].

3. Data Cleaning and Standardization:

- Remove undesired molecules: Filter out compounds with a molecular weight (MW) < 150 Da or > 1000 Da to focus on a drug-like range that considers cell permeability [16].

- Standardize structures: Use cheminformatics toolkits like RDKit or the MolVS library to canonicalize SMILES strings, neutralize charges, and generate canonical tautomers [21].

- Handle multi-component molecules: Split salts and other multi-component structures, retaining only the largest fragment [16] [21].

- Remove terminal sugars: For a more accurate assessment of the bioactive aglycon, utilize a deglycosylation tool to remove terminal sugar moieties from NPs [16].

- Filter elements: Remove molecules containing elements outside a defined set (e.g., H, B, C, N, O, F, Si, P, S, Cl, Se, Br, I) [16] [21].

Descriptor Calculation

Calculate the following 16 two-dimensional molecular descriptors for each standardized compound. This can be accomplished using software such as ChemAxon's Instant JChem or the RDKit library in Python [22] [16] [21].

Table 2: Essential Molecular Descriptors for PCA of Chemical Space

| Descriptor | Description | Interpretation in NP/SC Context |

|---|---|---|

| MW | Molecular Weight | NPs are generally larger [19]. |

| LogP | Partition coefficient (octanol/water) | Measures lipophilicity [22]. |

| TPSA | Topological Polar Surface Area | Related to polarity and hydrogen bonding [22]. |

| a_acc | Number of hydrogen bond acceptors | NPs often have more oxygen atoms [19]. |

| a_don | Number of hydrogen bond donors | NPs often have more donors [22]. |

| a_heavy | Number of heavy atoms | Indicator of molecular size [19]. |

| b_rotR | Fraction of rotatable bonds | Related to molecular flexibility [22]. |

| a_nN | Number of nitrogen atoms | SCs are often richer in nitrogen [19]. |

| a_nO | Number of oxygen atoms | NPs are often richer in oxygen [19]. |

| FCharge | Sum of formal charges | Influences solubility and interactions. |

| a_aro | Number of aromatic atoms | SCs typically have more aromatic character [19]. |

| chiral | Number of chiral centers | NPs have higher stereochemical complexity [16]. |

| rings | Number of rings | NPs tend to have more ring systems [19]. |

| stereo | Number of stereocenters | Key indicator of NP complexity [22] [16]. |

| fsp3 | Fraction of sp³ hybridized carbons | Critical measure of 3D complexity; higher in NPs [18] [16]. |

| a_spiro | Number of spiro atoms | Indicator of complex ring fusions; higher in NPs [16]. |

Performing Principal Component Analysis

- Data Matrix Preparation: Compile all calculated descriptors into a matrix where rows represent compounds and columns represent the 16 descriptors. Standardize the data (e.g., z-score normalization) so that each descriptor has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 to prevent variables with larger scales from dominating the analysis.

- PCA Execution: Perform PCA on the standardized matrix using statistical software or programming environments like R or Python (with libraries such as scikit-learn). The analysis will output the principal components and the proportion of variance explained by each.

- Visualization: Generate 2D or 3D scatter plots using the first two or three principal components. Color-code the data points by origin (NP vs. SC) and by key properties like Fsp3 to visually decode the structural patterns.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the experimental protocol for chemical space analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for Chemical Space Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics Library | Data standardization, descriptor calculation, and fingerprint generation [16] [21]. |

| Instant JChem | Commercial Cheminformatics Platform | Management of chemical data, batch calculation of physicochemical parameters [22]. |

| R / Python (scikit-learn) | Programming Environments | Performing Principal Component Analysis and statistical computations [22]. |

| VCC Lab ALOGPS | Web Service | Calculating additional properties like logP and aqueous solubility [22]. |

| MolVS | Open-source Library | Standardizing molecular structures (tautomers, charges, fragments) [21]. |

| FooDB | Public Database | Source of natural product structures, particularly food-related chemicals [21]. |

| ZINC Database | Public Database | Source of commercially available synthetic compound structures [16]. |

| Kakuol | Kakuol, CAS:18607-90-4, MF:C10H10O4, MW:194.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,4,6-Trihydroxybenzaldehyde | 2,4,6-Trihydroxybenzaldehyde, CAS:487-70-7, MF:C7H6O4, MW:154.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Library Design

The clear visualization of NP diversity has direct, practical implications for drug discovery. The finding that NPs explore vast, biologically relevant regions of chemical space that SCs do not reach provides a strong rationale for designing new libraries that capture these underrepresented features [18] [20]. Several strategies have emerged to bridge this gap:

- Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS): Uses NP scaffolds as starting points for library design, keeping compounds close to validated chemical space [20].

- Pseudo-Natural Products (PNPs): Combines NP fragments in novel arrangements not found in nature, creating new scaffolds that retain biological relevance while exploring uncharted territory [19] [20].

- Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS): Aims to generate high structural diversity, often incorporating NP-like features such as high Fsp3 and stereochemical complexity [20].

PCA can guide these efforts by quantifying how well a new library penetrates NP-like regions of chemical space. As demonstrated in one study, analyzing the component loadings can identify which structural parameters (e.g., number of oxygen atoms, stereochemical density, Fsp3) most influence the separation between NPs and SCs. Chemists can then target these specific parameters through synthetic modification to "shift" their compounds towards the NP region of the PCA plot [22]. This data-driven approach enables a more rational and effective exploration of nature's vast chemical repertoire for drug discovery.

Principal Component Analysis provides an unambiguous visual and quantitative demonstration of the superior structural diversity inherent in natural products compared to synthetic chemical libraries. The broader distribution of NPs in chemical space, characterized by greater molecular complexity, stereochemical richness, and distinct physicochemical properties, underscores their immense and irreplaceable value for drug discovery. By leveraging PCA as a guide for library design and analysis, researchers can move beyond the constraints of traditional drug-like chemical space, harnessing the evolutionary wisdom encoded in natural products to develop novel therapeutics for the most challenging biological targets.

Heavily Explored vs. Underexplored Regions in the NP Chemical Universe

Natural products (NPs) represent a vast and structurally diverse resource for drug discovery, comprising over 173,000 known structures that have evolved to interact with biological systems [23]. The concept of "chemical space" refers to a multidimensional universe where molecular properties define coordinates and relationships between compounds, with the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) encompassing molecules with demonstrated biological activity [1]. Within this framework, natural products occupy a strategic position, as they largely adhere to the Rule of Five while simultaneously exploring regions of chemical space not covered by synthetic compounds and available screening collections [24]. This renders them a valuable, unique, and necessary component of screening libraries used in drug discovery. Analyses of 10,495 natural products and 5,757 trade drugs reveal that natural products possess 1,748 different ring systems compared to 807 different ring systems found in trade drugs, demonstrating their superior structural diversity [23]. Despite this proven potential, significant portions of the natural product chemical universe remain underexplored, creating opportunities for discovering novel bioactive compounds with resistance-breaking properties and new mechanisms of action, particularly in challenging therapeutic areas like antimicrobial resistance [25].

Charting the NP Chemical Universe: Classification Approaches

Structural and Biosynthetic Classification Frameworks

The systematic organization of natural products enables effective navigation of their chemical space. Several classification approaches have been developed, with structural classification of natural products (SCONP) emerging as a powerful organizing principle [26]. SCONP arranges the scaffolds of natural products in a tree-like fashion, providing both an analysis- and hypothesis-generating tool for the design of natural product-derived compound collections [26]. This approach facilitates the identification of biologically relevant subfractions of chemical space and has been successfully applied in the development of novel inhibitor classes, such as selective and potent inhibitors of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 with cellular activity [26].

Alternative classification systems group natural products according to recurring structural features. For instance, flavonoid compounds are oxygenated derivatives of a specific aromatic ring structure, while alkaloids containing an indole ring are classified as indole alkaloids [27]. These structural classifications complement biosynthetic organization systems, which categorize compounds based on their metabolic pathways of origin within producing organisms [27]. Each classification approach offers distinct advantages for drug discovery, with structural systems enabling scaffold-based diversity analysis and biosynthetic systems facilitating genomics-guided discovery.

Computational Tools for NP Chemical Space Navigation

Computational methods have become indispensable for mapping and navigating natural product chemical space. ChemGPS-NP and Scaffold Hunter represent two widely used tools that enable researchers to explore biologically relevant NP chemical space in a focused and targeted fashion [24]. These cheminformatics platforms help bridge the gap between computational methods and compound library synthesis, integrating cheminformatics and chemical space analyses with synthetic chemistry and biochemistry to successfully identify novel small molecule modulators of protein function [24].

The analytical power of these tools stems from their ability to process multidimensional molecular descriptors that define the dimensionality of chemical space [1]. Recent advances include the development of more universal molecular descriptors, such as MAP4 fingerprints and neural network embeddings from chemical language models, which can accommodate entities ranging from small molecules to biomolecules [1]. These tools are particularly valuable for identifying "holes" in existing screening data sets—regions of chemical space that can and should be explored by chemistry and biology to discover new bioactive compounds [24].

Quantitative Comparison: Explored vs. Underexplored NP Regions

Table 1: Structural and Property-Based Comparison of Natural Products and Trade Drugs

| Characteristic | Natural Products | Trade Drugs | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Molecular Weight | 356 | 360 | [23] |

| Average log P value | 2.9 | 2.5 | [23] |

| Number of Ring Systems | 1,748 | 807 | [23] |

| Rule-of-5 Violations | Similar percentage | Similar percentage | [23] |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors | Fewer per molecule | More per molecule | [23] |

| Bridgehead Atoms | Much higher number | Lower number | [23] |

| Chiral Centers | Many more per molecule | Fewer per molecule | [23] |

Table 2: Heavily Explored vs. Underexplored Regions of NP Chemical Space

| Aspect | Heavily Explored Regions | Underexplored Regions | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Classes | Flavonoids, indole alkaloids, opium alkaloids, common scaffold systems | Macrocycles, RiPPs (ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides), metallodrugs | New structural motifs with potentially novel mechanisms of action [27] [28] [1] |

| Source Organisms | Soil-derived actinomycetes, terrestrial plants | Microbes from extreme environments, marine symbionts, cyanobacteria, hot sulfur springs | Unique biosynthetic pathways and enzymatic transformations [25] |

| Chemical Space Properties | Drug-like properties, Rule-of-5 compliance, well-characterized pharmacology | Beyond Rule of 5 (bRo5) compounds, protein-protein interaction inhibitors, PROTACs | Challenges in synthesis and optimization, but potential for targeting difficult therapeutic areas [28] [1] |

| Discovery Approaches | Bioactivity-guided fractionation, traditional natural product chemistry | Genome mining, metabolomics, bioengineering, synthetic biology | Access to cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters and previously inaccessible chemical diversity [25] [23] |

The data reveal that while natural products share many drug-like properties with trade drugs, they explore significantly more structural diversity, particularly in complex ring systems and stereochemistry [23]. This structural complexity contributes to their biological relevance but also presents challenges for synthesis and modification. The underexplored regions of NP chemical space are characterized by structural classes that fall outside traditional drug-like property space, source organisms from extreme or difficult-to-access environments, and novel biosynthetic pathways [25] [28] [1].

Heavily Explored Regions of NP Chemical Space

Traditional Natural Product Classes and Scaffolds

Certain classes of natural products have been extensively investigated due to their historical therapeutic success and relative accessibility. Flavonoids and alkaloids represent two such heavily explored families, with well-established biosynthetic pathways, known pharmacological activities, and extensive structure-activity relationship data [27]. These compounds typically exhibit favorable drug-like properties, with molecular weights and log P values falling within ranges comparable to approved drugs [23]. The structural classification of natural products (SCONP) has further illuminated that certain molecular scaffolds recur frequently among known natural products, creating regions of chemical space that have been systematically explored for drug discovery [26].

The heavy exploration of these regions is evidenced by the fact that more than 100 marketed macrocycle drugs are almost exclusively derived from natural products, yet this structural class remains poorly explored within targeted drug discovery efforts [28]. Similarly, natural products have contributed significantly to approved drugs across multiple therapeutic areas: 78% of antibacterial drugs, 75% of platelet aggregation inhibitors, 61% of anticancer drugs, 48% of anti-hypotensive drugs, 47.6% of antiulcer drugs, and 32.5% of anti-inflammatory drugs have a natural origin [23]. This extensive exploration has generated robust structure-activity relationship data for these compound classes but has also led to diminishing returns in discovering truly novel chemotypes from traditional sources.

Limitations and Repetition in Explored Regions

The heavy focus on specific natural product classes and source organisms has resulted in significant redundancy in discovery efforts. Recent analyses indicate that although the total number of characterized natural products has increased over the last decades, only a small percentage of recently discovered compounds possess previously unknown chemical structures [25]. This repetition stems from several factors: the repeated isolation of known compounds from related species, the focus on easily cultivable microorganisms from similar ecological niches, and the application of standardized extraction and isolation procedures that selectively capture certain chemical classes while missing others.

This redundancy presents a substantial challenge for drug discovery, particularly in areas like antibiotic development where structurally new chemicals are urgently required for resistance-breaking properties [25]. The known natural product chemical space likely represents only "the tip of the iceberg," with significant biosynthetic potential remaining concealed in underexplored organisms, environments, and biosynthetic pathways [25]. Overcoming this limitation requires deliberate exploration of untapped regions of NP chemical space through innovative approaches and technologies.

Underexplored Regions of NP Chemical Space

Structural Classes with Discovery Potential

Several structural classes of natural products remain underexplored despite their significant potential for drug discovery. Macrocycles, defined as compounds containing rings of 12 or more atoms, represent a particularly promising yet underexploited structural class [28]. These compounds provide diverse functionality and stereochemical complexity in a conformationally pre-organized ring structure, which can result in high affinity and selectivity for protein targets while preserving sufficient bioavailability to reach intracellular locations [28]. Macrocycles have demonstrated repeated success when addressing targets that have proved highly challenging for standard small-molecule drug discovery, especially in modulating macromolecular processes such as protein-protein interactions [28].

Other underexplored structural classes include ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), which exhibit remarkable structural diversity and bioactivities [25]. Recent research has identified ribosomally derived lipopeptides containing distinct fatty acyl moieties as a promising area for exploration [25]. Additionally, metal-containing natural products represent a structurally and functionally important class that is commonly excluded from standard chemoinformatics analyses due to modeling challenges [1]. The difficulty of modeling these regions of BioReCS should not justify their exclusion from systematic exploration, as they may offer unique therapeutic opportunities.

Underexplored Source Organisms and Environments

The biosynthetic potential of certain microbial groups and extreme environments remains largely untapped. Cyanobacteria and microbes that colonize extreme habitats represent talented but neglected natural product producers [25]. These organisms often possess unique biosynthetic pathways evolved to produce specialized metabolites under challenging environmental conditions, resulting in chemical structures not found in organisms from conventional sources.

Recent advances in metagenomics have revealed that the wealth of publicly available (meta)genomes conceals significant biosynthetic potential that has yet to be elucidated [25]. One comprehensive study of the global ocean microbiome uncovered extensive biosynthetic diversity, with thousands of new biosynthetic gene clusters identified in marine microorganisms [25]. The isolation of natural products from habitats and organisms previously thought to lack natural product biosynthesis potential (e.g., hot sulfur springs) further supports the hypothesis that known natural product chemical space represents only a fraction of what exists in nature [25].

Dark Chemical Matter and Inactive Compounds

A particularly intriguing underexplored region of biologically relevant chemical space consists of so-called "dark chemical matter" – compounds that have repeatedly failed to show activity in high-throughput screening assays [1]. These molecules represent the non-biologically relevant portions of chemical space and provide crucial boundary conditions for understanding bioactivity. Recent efforts have led to the development of InertDB, a curated collection of 3,205 experimentally confirmed inactive compounds supplemented with 64,368 putative inactive molecules generated using deep generative artificial intelligence models [1]. Understanding why these compounds lack activity can provide equally valuable insights for drug discovery as studying successful bioactive molecules.

Experimental Protocols for Exploring Underexplored NP Space

Genomics-Guided Discovery Workflow

The integration of genomic information with natural product chemistry has emerged as a powerful approach for targeted exploration of underexplored regions of NP chemical space. The following protocol outlines a genomics-guided discovery workflow:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Genomics-Guided NP Discovery

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic DNA Libraries | Source of biosynthetic gene clusters from unculturable microorganisms | Provides access to genetic potential of microbial communities without cultivation [25] |

| Heterologous Expression Systems | Host organisms for expressing foreign biosynthetic gene clusters | Enables production of natural products from unculturable or genetically intractable organisms [25] |

| Bioinformatics Tools (e.g., antiSMASH) | Identification and analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters in genomic data | Guides target selection and predicts structural features of encoded natural products [25] |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | Detection and structural characterization of novel natural products | Links biosynthetic gene clusters to their metabolic products through metabolomics [23] |

Protocol Steps:

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Collect environmental samples from underexplored niches (e.g., extreme environments, marine sediments). Extract high-molecular-weight DNA suitable for metagenomic library construction [25].

- Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis: Perform whole-metagenome sequencing using Illumina or PacBio platforms. Analyze sequence data using specialized bioinformatics tools (e.g., antiSMASH, PRISM) to identify biosynthetic gene clusters with novel architectures [25].

- Heterologous Expression: Clone promising biosynthetic gene clusters into suitable expression hosts (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor, E. coli). Optimize expression conditions to activate silent gene clusters [25].

- Metabolite Analysis and Isolation: Compare metabolic profiles of expression hosts containing target gene clusters against control strains using LC-HRMS. Isplicate novel compounds using bioactivity-guided or mass-guided fractionation [25] [23].

- Structural Elucidation and Bioactivity Testing: Determine structures of novel compounds using NMR, MS/MS, and other spectroscopic techniques. Evaluate bioactivity against target disease models, with particular attention to resistance-breaking antimicrobial activity [25].

Bioengineering and Synthetic Biology Approaches

Bioengineering provides powerful methods to access underexplored regions of natural product chemical space through targeted modification of biosynthetic pathways:

Protocol Steps:

- Pathway Refactoring: Redesign complete biosynthetic gene clusters using synthetic biology principles to optimize expression and enable genetic manipulation [25].

- Combinatorial Biosynthesis: Exchange domains in modular biosynthetic enzymes (e.g., polyketide synthases, nonribosomal peptide synthetases) to create novel hybrid pathways [25].

- Precursor-Directed Biosynthesis: Supplement producing organisms with non-natural substrate analogs to shunt biosynthesis toward novel derivatives [25].

- Enzyme Engineering: Apply directed evolution or structure-based design to modify substrate specificity of key biosynthetic enzymes, enabling production of "non-natural" natural products [25].

- Pathway Activation: Employ genetic techniques (promoter engineering, regulatory gene overexpression) to activate silent/cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters [25].

Visualization of NP Chemical Space Exploration Strategies

The systematic exploration of underexplored regions of natural product chemical space requires an integrated approach combining multiple scientific disciplines and methodologies. The following diagram illustrates the workflow for discovering novel natural products from underexplored sources, highlighting the interdisciplinary nature of modern natural product research:

Table 4: Essential Research Tools and Resources for NP Chemical Space Exploration

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application in NP Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Space Navigation | ChemGPS-NP, Scaffold Hunter | Guide exploration of biologically relevant NP chemical space in a focused and targeted fashion [24] |

| Bioinformatics Platforms | antiSMASH, PRISM, MIBiG | Identify and analyze biosynthetic gene clusters in genomic and metagenomic data [25] |

| Analytical Technologies | LC-HRMS, MS Imaging, NMR | Detect, characterize, and visualize natural products in complex biological matrices [23] |

| Genomic Resources | Metagenomic libraries, Heterologous expression systems | Access biosynthetic potential of unculturable microorganisms and engineer biosynthetic pathways [25] |

| Specialized Compound Libraries | Macrocyclic libraries, RiPP libraries, Dark chemical matter collections | Focus screening efforts on underexplored regions of chemical space [28] [1] |

The systematic exploration of natural product chemical space represents a crucial frontier in drug discovery, particularly as resistance to existing therapies grows and challenging targets require innovative chemical solutions. While heavily explored regions of NP chemical space have provided numerous therapeutic agents, they face diminishing returns in yielding truly novel chemotypes. In contrast, underexplored regions—including macrocycles, RiPPs, metabolites from extreme environments, and cryptic biosynthetic pathways—offer significant opportunities for discovering compounds with resistance-breaking properties and novel mechanisms of action. The integrated application of genomics, bioinformatics, synthetic biology, and advanced analytical technologies provides powerful methods to navigate and populate these underexplored regions of natural product chemical space. As computational tools continue to evolve and our understanding of biosynthetic pathways expands, targeted exploration of these underexplored regions will play an increasingly important role in addressing unmet medical needs through natural product-inspired drug discovery.

The concept of the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) provides a foundational framework for modern drug discovery. BioReCS encompasses all molecules with biological activity—both beneficial and detrimental—spanning diverse application areas including drug discovery, agrochemistry, and natural product research [1]. This chemical universe is vast, with estimates suggesting the existence of up to 10^60 drug-like compounds, creating a fundamental challenge for researchers seeking to identify novel therapeutic agents [29]. Within this expansive universe, natural products (NPs) occupy a particularly privileged region, characterized by unique structural complexity and high relevance to human biology. Analyses reveal that over half of approved small-molecule drugs originate directly or indirectly from natural products, highlighting their enduring importance [12].

The structural and physicochemical properties of natural products differ significantly from typical synthetic compounds. Natural products often feature greater stereochemical complexity, higher sp³-hybridized carbon counts, more oxygen atoms, and intricate ring systems that confer sophisticated three-dimensional architectures [30]. These characteristics enable natural products to interact with challenging biological targets, including protein-protein interactions, which have proven difficult to modulate with conventional synthetic compounds [30]. Despite the known structural diversity of natural products, current databases document approximately 1.1 million natural products, with only about 10% readily obtainable for experimental testing, creating a significant accessibility challenge [12]. This gap between known structures and readily testable compounds represents a critical bottleneck in natural product-based drug discovery.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Natural Product Chemical Space

| Property | Natural Products | Synthetic/Drug-like Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Complexity | High (multiple stereocenters, complex ring systems) | Variable, often lower |

| sp³ Hybridized Carbons | Higher fraction (Fsp³) | Lower fraction |

| Oxygen Content | High | Variable |

| Number of Aromatic Rings | Generally lower | Generally higher |

| Relevance to Drug Discovery | >50% of approved drugs NP-derived | Foundation of combinatorial libraries |

| Readily Accessible Compounds | ~10% of known structures | High percentage |

Charting Unexplored Territories in Natural Product Chemical Space

Analytical Tools for Navigation

Systematic exploration of natural product chemical space requires specialized computational tools that can map its complex topography. Platforms such as ChemGPS-NP and Scaffold Hunter enable researchers to navigate biologically relevant regions in a focused manner, identifying both densely populated and sparsely explored areas [24]. These cheminformatic tools employ dimensionality reduction techniques to project high-dimensional chemical descriptor data into visualizable and interpretable formats, allowing researchers to identify structural patterns and anomalies across large compound collections [1].

Recent advances in molecular representation have been critical for effective chemical space analysis. While traditional descriptors were optimized for small organic molecules, newer approaches like the MAP4 fingerprint and neural network embeddings from chemical language models offer more universal representations that can accommodate diverse molecular classes ranging from small molecules to peptides and even metallodrugs [1]. These improved descriptors facilitate more meaningful comparisons across different regions of chemical space and enable the identification of truly novel scaffolds with potential bioactivity.

Underexplored Regions and Dark Chemical Matter

Analysis of natural product chemical space reveals several underexplored regions with high potential for drug discovery. Certain structural classes remain underrepresented in current screening collections, including metal-containing molecules, large and complex natural products, macrocycles, protein-protein interaction (PPI) modulators, PROTACs, and mid-sized peptides [1]. Many of these compounds fall into the "beyond Rule of 5" (bRo5) category, presenting both challenges and opportunities for drug development [1].

Marine natural products represent another distinctive region of chemical space, characterized by larger molecular weights and greater hydrophobicity compared to their terrestrial counterparts [12]. Particularly interesting are natural products derived from deep-sea and extremophile organisms, which often display novel scaffolds and notable bioactivities honed by adaptation to unique environmental conditions [12]. The continued discovery of such structurally distinct compounds highlights the value of exploring diverse biological sources.

Beyond these structural classes, the concept of "dark chemical matter"—compounds that consistently show no activity in high-throughput screens—provides valuable negative data that helps define the boundaries of BioReCS [1]. Similarly, databases of curated inactive compounds, such as InertDB, which includes both experimentally determined and AI-generated putative inactive molecules, contribute to our understanding of the structural features that separate bioactive from non-bioactive chemical space [1].

Table 2: Key Public Databases for Exploring Natural Product Chemical Space

| Database | Scope | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| COCONUT (Collection of Open Natural Products) | Comprehensive NP collection | >400,000 fully characterized natural products [31] |

| ChEMBL | Bioactive drug-like molecules | Extensive biological activity annotations [1] |

| PubChem | Chemical substances and bioactivities | Large repository with screening data [1] |

| Super Natural II | Natural products | Includes predicted bioactivity and pathways [12] |

| NAPRORE-CR | Costa Rican natural products | Geographically focused NP database [12] |

| PeruNPDB | Peruvian natural products | Regional focus for drug screening [12] |

Strategic Approaches to Populating Chemical Space through Synthesis

Natural Product-Inspired Synthesis Strategies

Several sophisticated synthesis strategies have emerged to systematically populate promising regions of natural product chemical space with novel compounds. These approaches leverage the structural information encoded in natural products while introducing significant diversity to explore surrounding chemical space.

Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS) proceeds from the premise that natural products are "privileged structures" with inherent biological relevance. This strategy employs natural products as starting points for designing focused libraries that retain core structural elements of the original bioactive compound while introducing strategic modifications [32] [30]. For example, Waldmann's development of an oxepane-based library inspired by bioactive natural products like heliannuol B and zoapatanol led to the discovery of novel Wnt signaling modulators that interact with the previously undrugged target Vangl1 [32]. BIOS libraries typically contain fewer compounds than traditional combinatorial libraries but demonstrate higher hit rates due to their foundation in evolutionarily validated scaffolds.

Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) aims to generate broad structural diversity through branching reaction pathways that produce compounds with varied skeletons and stereochemistries from common intermediates [32] [30]. Unlike target-oriented synthesis, DOS employs forward synthetic analysis to create structurally complex and diverse libraries that populate expansive regions of chemical space. A prominent example includes Schreiber's work generating a library of 2,070 macrolactone-based small molecules, which led to the discovery of robotnikinin—a potent inhibitor of the Hedgehog signaling pathway with potential applications in cancer treatment [30]. DOS libraries are particularly valuable for phenotypic screening campaigns where the biological targets may not be fully characterized.

Pharmacophore-Directed Retrosynthesis (PDR) represents a more recent strategy that integrates synthetic planning with the identification of key structural features essential for bioactivity [32]. This approach begins with a retrospective analysis of structure-activity relationships to identify critical pharmacophoric elements, then designs synthetic routes that maximize opportunities to generate analogs exploring variations in these key features. PDR aims to balance the efficiency of total synthesis with the systematic investigation of structure-activity relationships throughout the synthetic process.

Diagram 1: NP-Inspired Synthesis Strategies

Advanced Methodologies for Late-Stage Molecular Diversification

Beyond comprehensive library synthesis strategies, recent methodological advances enable precise molecular editing that can dramatically expand accessible chemical space from advanced intermediates. These approaches are particularly valuable for lead optimization phases where subtle structural modifications can significantly improve drug properties.

Skeletal Editing techniques allow direct modification of molecular frameworks through atom insertion, deletion, or exchange. A groundbreaking example is the development of sulfenylcarbene-mediated carbon atom insertion into N-heterocycles, which enables the transformation of existing drug scaffolds into new candidates by adding just one carbon atom at room temperature under metal-free conditions [33]. This method achieves yields up to 98% and is compatible with DNA-encoded library technology, making it particularly valuable for late-stage diversification of lead compounds [33]. The ability to perform such precise molecular surgery represents a paradigm shift in medicinal chemistry, potentially reducing drug development costs by enabling efficient renovation of existing molecular structures rather than requiring de novo synthesis.

Ring Distortion of Natural Products capitalizes on the complex ring systems found in many natural products by subjecting them to reaction conditions that dramatically rearrange their core structures. This approach can generate diverse, natural product-like compounds that would be challenging to access through conventional synthesis. The resulting libraries maintain the three-dimensional complexity and fraction of sp³-hybridized carbons characteristic of bioactive natural products while exploring unprecedented structural space around the original scaffold.

Hybrid Natural Products combine structural elements from two or more biologically active natural products to create novel compounds with potentially enhanced or dual activities. This strategy mimics nature's own evolutionary approach, as exemplified by the potent anticancer natural product vincristine, which represents a hybrid of the simpler alkaloids vindoline and catharanthine [30]. Synthetic hybridization enables the exploration of chemical space between known bioactive regions, potentially yielding compounds with novel mechanisms of action.

Table 3: Experimental Approaches for Chemical Space Exploration

| Methodology | Key Reagents/Techniques | Applications | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal Editing | Sulfenylcarbene reagents, metal-free conditions | Late-stage functionalization, lead optimization | Bench-stable reagents, room temperature operation, compatibility with DNA-encoded libraries [33] |