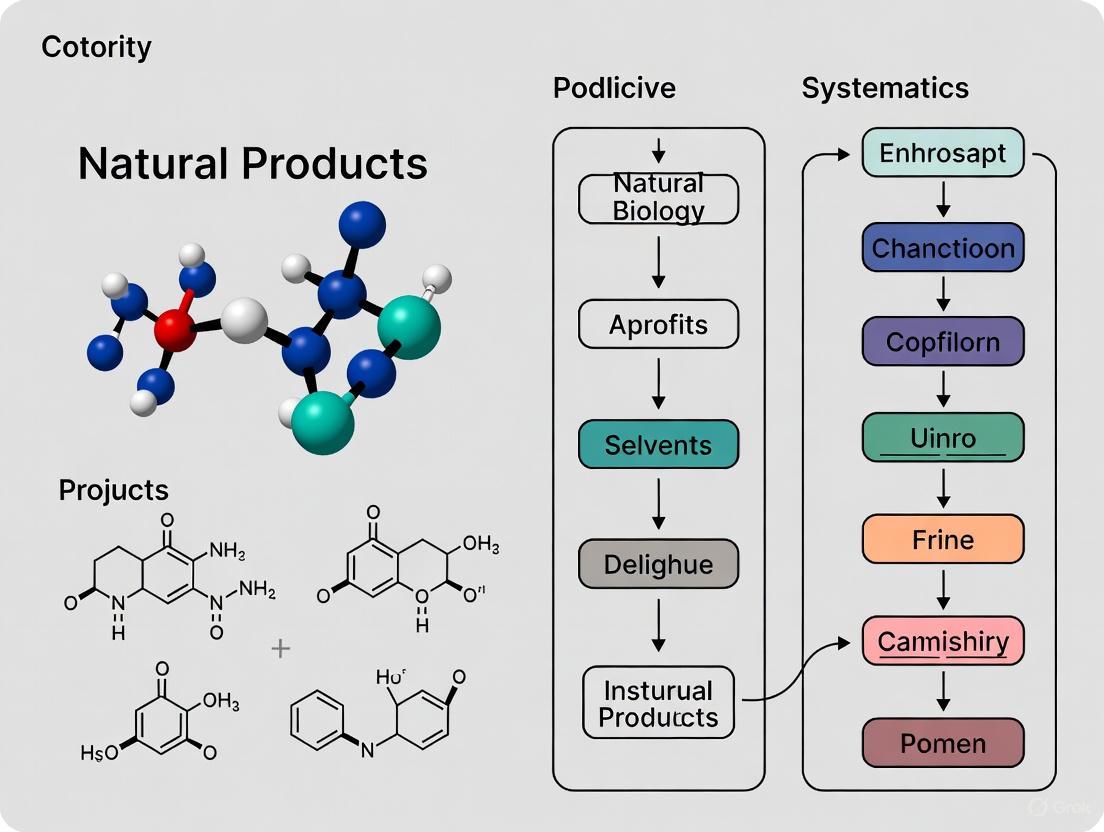

Natural Products at the Crossroads of Chemical Biology and Systematics: A New Paradigm for Drug Discovery

This review synthesizes contemporary advances and methodologies at the intersection of natural product research, chemical biology, and biological systematics.

Natural Products at the Crossroads of Chemical Biology and Systematics: A New Paradigm for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This review synthesizes contemporary advances and methodologies at the intersection of natural product research, chemical biology, and biological systematics. It explores the foundational relationship between taxonomic classification and metabolic diversity, highlighting how chemosystematic approaches guide the discovery of novel bioactive compounds. The article critically assesses cutting-edge technologies—including cell-free biosynthetic systems, AI-powered target prediction, and integrated multi-omics strategies—for elucidating and exploiting natural product function. It further addresses persistent challenges in characterization and supply, offering optimization frameworks for troubleshooting isolation and production bottlenecks. By validating these approaches through comparative analysis of chemical space and clinical success stories, this work provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to harness natural products for therapeutic innovation.

The Chemosystematic Link: How Taxonomy Guides Chemical Discovery

Natural products (NPs) represent a cornerstone of chemical biology and therapeutic development, offering unparalleled structural diversity honed by millions of years of evolutionary selection [1]. These compounds, originating from plants, fungi, bacteria, and marine organisms, function as defense chemicals, signaling agents, and ecological mediators, making them particularly valuable for drug discovery and systematics research. Their chemical space is characterized by elevated molecular complexity, including higher proportions of sp³-hybridized carbon atoms, increased oxygenation, and rigid molecular frameworks that facilitate optimal interactions with biological targets [1]. Within this expansive chemical universe, four major classes—terpenoids, alkaloids, polyketides, and peptides—emerge as fundamental pillars, each with distinct biosynthetic origins, structural features, and biological activities. The study of these compounds now integrates traditional methodologies with modern technological platforms including genome mining, synthetic biology, and artificial intelligence, creating a powerful framework for elucidating biosynthetic pathways and engineering novel bioactive molecules [2] [1].

Terpenoids: Structural Diversity and Biosynthetic Engineering

Structural Classification and Biosynthetic Pathways

Terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, constitute one of the largest and most structurally diverse families of natural products, with over 80,000 identified compounds [2]. These metabolites are biosynthesized through two primary pathways: the mevalonate (MVA) pathway in the cytosol of eukaryotes and some bacteria, and the methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in prokaryotes and plant plastids. The fundamental building blocks, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), are condensed by prenyltransferases (PTs) to generate prenyl diphosphates of varying chain lengths (Câ‚…, Câ‚â‚€, Câ‚â‚…, Câ‚‚â‚€, Câ‚‚â‚…, C₃₀). Terpene synthases (TSs) then catalyze the cyclization and rearrangement of these linear precursors into diverse carbon skeletons, which are further functionalized by tailoring enzymes such as cytochrome P450s oxygenases (P450), glycosyltransferases (GT), and acyltransferases (ACT) [2].

Table 1: Major Terpenoid Subclasses and Representative Structures

| Subclass | Carbon Skeleton | Representative Compounds | Biological Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpenoids | Câ‚â‚€ | Menthol, Limonene | Antimicrobial, flavoring agents |

| Sesquiterpenoids | Câ‚â‚… | Artemisinin [2], Bisabolene | Antimalarial [2], anti-inflammatory [2] |

| Diterpenoids | Câ‚‚â‚€ | Paclitaxel [2], Retinol | Anticancer [2], vitamin A precursor |

| Triterpenoids | C₃₀ | Squalene, Lanosterol | Sterol precursors, anti-inflammatory |

| Tetraterpenoids | C₄₀ | β-Carotene, Lycopene | Antioxidants, vitamin A precursors |

Experimental Approaches for Terpenoid Discovery and Production

The exploration of terpenoid chemical space has been revolutionized by integrated approaches that combine genomics, synthetic biology, and analytical technologies.

Genome Mining and Heterologous Expression: Identification of terpene synthase genes (TSs) through genome sequencing enables the discovery of novel terpenoid pathways. Functional characterization often requires heterologous expression in microbial hosts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Aspergillus oryzae [2]. The Heterologous EXpression (HEX) synthetic biology platform has enabled high-throughput screening of numerous fungal terpene and polyketide gene clusters in S. cerevisiae, leading to the identification of previously inaccessible terpenoids [2].

Automated High-Throughput Workflows: Automated workstations facilitate the transfer of numerous terpene gene clusters into yeast, with subsequent cultivation in microtiter plates. Metabolite extraction and LC-MS/MS analysis enable rapid structural characterization of terpene products, significantly accelerating discovery timelines [2].

Metabolic Engineering for High-Yield Production: The "Targeted Synthetic Metabolism" strategy involves optimizing protein ratios in terpene biosynthetic pathways through in vitro titration reactions, followed by systematic engineering of these pathways in microbial hosts to achieve stable and efficient synthesis of high-value terpenes [2]. This approach addresses the challenge of low product yields that often impedes bioactivity evaluation.

Figure 1: High-Throughput Terpenoid Discovery Workflow

Alkaloids: Nitrogen-Containing Bioactive Compounds

Structural Classification and Biosynthetic Origins

Alkaloids are low-molecular-weight nitrogenous compounds, typically basic in nature, that contain one or more nitrogen atoms, usually within a heterocyclic ring [3] [4]. These compounds are biosynthesized primarily from amino acid precursors such as tyrosine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, lysine, or ornithine, though some incorporate terpenoid or other structural moieties [5]. The structural diversity of alkaloids arises from variations in their carbon skeletons, nitrogen incorporation patterns, and post-modification reactions including oxidation, methylation, and glycosylation.

Table 2: Major Alkaloid Classes and Their Characteristics

| Class | Amino Acid Precursor | Representative Compounds | Pharmacological Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrrolidine & Tropane | Ornithine | Cocaine [3], Hyoscyamine | Stimulant, anticholinergic [3] |

| Piperidine & Quinolizidine | Lysine | Coniine [3], Lupinine | Toxic, nicotinic activity [3] |

| Indole | Tryptophan | Vinblastine, Strychnine [3] | Anticancer, toxic [3] |

| Isoquinoline | Tyrosine | Morphine [3], Codeine | Analgesic [3] |

| Imidazole | Histidine | Pilocarpine | Parasympathomimetic |

| Terpenoid | Secologanin/Tryptophan | Dendrobine [5] | Neuroprotective, anti-viral [5] |

The genus Dendrobium exemplifies alkaloid diversity, with at least 60 structurally characterized alkaloids including 35 sesquiterpene alkaloids, 14 indolizidine alkaloids, five pyrrolidine alkaloids, four phthalide alkaloids, two organic amine alkaloids, one imidazole type, and one indole alkaloid [5]. Dendrobine from D. nobile has demonstrated significant neuroprotective effects in cortical neurons injured by oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion and prevents Aβ₂₅₋₃₅-induced neuronal and synaptic loss [5].

Experimental Protocols for Alkaloid Research

Biosynthetic Pathway Elucidation: Alkaloid biosynthesis involves complex, often compartmentalized pathways that can span multiple cell types. In Catharanthus roseus, for example, the biosynthesis of vinblastine and vincristine involves different enzymatic steps in various cellular compartments, with final assembly steps occurring in a different cell type than the early steps, necessitating intercellular transport of metabolic intermediates [4]. Modern approaches combine stable isotope labeling (¹³C, ¹âµN, ²H) with NMR and MS analysis to trace precursor incorporation [6]. Gene knockout experiments in producing organisms help identify biosynthetic intermediates and shunt products.

Heterologous Production in Microbial Hosts: Reconstruction of alkaloid biosynthetic pathways in microorganisms like E. coli and S. cerevisiae enables production of complex alkaloids and novel analogs. For benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis, researchers have expressed plant-derived norcoclaurine synthase (NCS), 6-O-methyltransferase (6OMT), coclaurine N-methyltransferase (CNMT), and 4′-O-methyltransferase (4′OMT) along with a microbial monoamine oxidase (MAO) to synthesize reticuline from dopamine in E. coli [4]. Further expression of tailoring enzymes in S. cerevisiae has enabled production of magnoflorine and scoulerine from reticuline [4].

Analytical Techniques for Alkaloid Characterization:

- Extraction: Plant material is typically extracted with methanol or ethanol under reflux, followed by acid-base extraction to separate alkaloids from other compounds.

- Separation: Crude extracts are fractionated using silica gel column chromatography, with increasing polarity of organic solvents.

- Purification: Final purification employs techniques including preparative TLC, HPLC, or countercurrent chromatography.

- Structural Elucidation: Advanced NMR (¹H, ¹³C, 2D experiments) and high-resolution mass spectrometry provide structural information.

Figure 2: Generalized Alkaloid Biosynthesis Pathway

Polyketides: Modular Assembly Line Biosynthesis

Structural Diversity and Biosynthetic Logic

Polyketides represent one of the largest classes of natural products with significant medicinal applications, including antibiotic, antifungal, anticancer, and immunosuppressant activities [7]. These compounds are synthesized by polyketide synthases (PKSs), which share a core biosynthetic logic with fatty acid synthases, iteratively building complex molecules from simple precursors like acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA [7]. The structural diversity of polyketides arises from variations in the selection of extender units, the degree of β-carbon processing after each condensation, and post-assembly tailoring reactions.

Type II polyketide synthases are iterative enzymes that produce aromatic compounds through a minimal PKS consisting of a ketosynthase chain-length factor (KS-CLF) heterodimer and an acyl carrier protein (ACP) [7]. The nascent poly-β-ketone chain undergoes specific cyclization and aromatization patterns dictated by the KS-CLF, followed by tailoring modifications such as oxidations, glycosylations, and methylations.

Engineering Polyketide Biosynthesis

Gene Knock-Out and Mutational Analysis: Systematic gene knock-out experiments in producing organisms enable elucidation of biosynthetic pathways and isolation of intermediates. In the mupirocin biosynthetic pathway (mup gene cluster), mutation of specific genes resulted in a complete switch from production of primarily pseudomonic acid A (PA-A) to exclusive production of PA-B, revealing unexpected biosynthetic relationships [6]. Similar experiments with the thiomarinol BGC (tml) produced marinolic acid and related analogs lacking the pyrrothine moiety [6].

Combinatorial Biosynthesis and Pathway Engineering: Domain swapping between related PKS systems generates hybrid enzymes that produce novel polyketides. In fungal tenellin and bassianin biosynthesis, which involve multi-domain PKS-NRPS hybrids, domain swapping between the two biosynthetic gene clusters followed by heterologous expression in Aspergillus oryzae produced numerous new metabolites in high yields, revealing key elements controlling polyketide chain length and methylation patterns [6].

Optimization of Production Strains: Genetic engineering of producing strains can improve titers and simplify metabolite profiles. For instance, engineering of Pseudomonas fluorescens to block the 10,11-epoxidation in mupirocin biosynthesis diverted the pathway to produce exclusively pseudomonic acid C (PA-C) as the main product, which demonstrated improved stability while retaining antibiotic activity [6].

Table 3: Experimentally Determined Production Yields of Engineered Polyketides

| Polyketide | Native Producer | Engineered System | Yield Improvement | Key Modification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonic Acid C | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Engineered P. fluorescens (Δoxidase) | High titre as sole product [6] | Blocked 10,11-epoxidation [6] |

| Novel Tenellin Analogs | Beauvaria species | Aspergillus oryzae (heterologous) | High yields [6] | Domain swapping between PKS-NRPS [6] |

| Marinolic Acid | Pseudoalteromonas sp. | Pseudoalteromonas sp. (ΔNRPS) | Main product [6] | Deletion of NRPS gene cluster [6] |

Peptides: Structural and Functional Diversity

Ribosomal and Non-Ribosomal Peptides

Bioactive peptides from natural sources represent a rapidly expanding class of therapeutics with diverse applications, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, antihypertensive, and anticancer activities [8]. These compounds are broadly categorized into ribosomal peptides (synthesized through the translation machinery and often post-translationally modified) and non-ribosomal peptides (synthesized by NRPS enzymes without direct RNA template).

Apidaecin, a proline-rich antimicrobial peptide (PrAMP) produced by honeybees (Apis mellifera), represents a novel class of non-lytic antimicrobials that inhibit bacterial growth by targeting intracellular processes rather than disrupting membranes [9]. Apidaecin Ib (H-GNNRPVYIPQPRPPHPRL-OH) and its synthetic derivative Api-137 exhibit activity against Gram-negative bacteria including E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumonia by inhibiting translation termination through stabilization of the quaternary complex of ribosome-apidaecin-tRNA-release factor [9].

Structure-Activity Relationship Studies

Structural Modifications and Functional Analysis: Structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies of apidaecin have identified the C-terminal five amino acids (P/z-H/z-P-R-X, where z = aromatic amino acid and X = any amino acid except A,S,G) as the core pharmacophore responsible for antimicrobial activity [9]. Modifications of key residues dramatically affect potency:

- Replacement of Arg17 with homoarginine (sidechain length difference) reduced activity 16-fold (MIC = 2.5 μM vs. 0.16 μM for Api-137)

- Replacement with citrulline (urea instead of guanidinium) reduced activity 128-fold (MIC = 20 μM) due to altered H-bonding capacity [9]

- Mono-methylation of Arg17 retained near-native activity (MIC = 0.3 μM) [9]

C-Terminal Modifications: The carboxylic acid of the C-terminal Leu18 is essential for activity, as replacement with decarboxy-leucine (complete removal of carboxylic acid) abolished antimicrobial activity (MIC > 40 μM) [9]. Substitution with leucinol or phenylalaninol (carboxyl replaced with alcohol) reduced but did not eliminate activity, with MIC values of 5 μM for l-leucinol and l-phenylalaninol derivatives [9].

Antioxidant Peptide SAR: Antioxidant peptides from natural proteins exhibit structure-activity relationships dependent on amino acid composition, sequence, and molecular weight. Key features enhancing antioxidant activity include:

- Presence of hydrophobic amino acids (Leu, Val, Phe, Trp) that improve lipid solubility and interaction with free radical species

- Histidine-containing peptides that exhibit metal ion chelating capacity and radical scavenging

- Low molecular weight peptides (typically 500-1500 Da) with enhanced cellular absorption

- Specific amino acid sequences that determine hydrogen-donating ability and electron transfer efficiency [8]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Natural Product Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Host Systems | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Aspergillus oryzae, E. coli | Expression of biosynthetic gene clusters from diverse organisms [2] [6] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas systems, Recombineering protocols | Targeted gene knock-outs, pathway engineering, activation of silent clusters [1] |

| Bioinformatics Platforms | antiSMASH [6], DeepBGC, GNPS, Pfam [2] | Genome mining, BGC identification, metabolite annotation [2] [1] |

| Analytical Standards | Stable isotope-labeled precursors (¹³C, ¹âµN, ²H) | Metabolic flux analysis, biosynthetic pathway elucidation [6] |

| Enzyme Assay Components | SAM (S-adenosyl methionine), NADPH, acetyl-CoA | In vitro characterization of tailoring enzymes, substrate specificity studies |

| Chromatography Materials | Silica gel, C18 reverse-phase, Sephadex LH-20 | Extraction, fractionation, and purification of natural products [3] |

| 3,5-Dichloro-2-hydroxybenzamide | 3,5-Dichloro-2-hydroxybenzamide|CAS 17892-26-1 | 3,5-Dichloro-2-hydroxybenzamide is a chemical intermediate for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Tris(2,2,6,6-tetramethylheptane-3,5-dionato-O,O')praseodymium | Tris(2,2,6,6-tetramethylheptane-3,5-dionato-O,O')praseodymium, CAS:15492-48-5, MF:C33H57O6Pr, MW:690.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Discovery Workflows in Chemical Biology

Modern natural product research employs integrated workflows that combine multi-omics technologies, synthetic biology, and computational approaches to navigate chemical space efficiently.

Genome-Mining Guided Discovery: The standard workflow begins with genome sequencing of potential producer organisms, followed by bioinformatic analysis using tools like antiSMASH to identify biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [2] [1]. Clusters of interest are prioritized based on novelty indices and phylogenetic analysis compared to known BGCs. Selected clusters are then activated through various strategies: heterologous expression in optimized chassis strains, promoter engineering in native hosts, or cultivation under simulated natural environmental conditions using iChip technology [1].

AI-Enhanced Natural Product Discovery: Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms are increasingly applied to predict BGC boundaries, substrate specificity of biosynthetic enzymes, and even three-dimensional structures of novel natural products [2] [1]. Tools like DeepBGC and related platforms use deep learning to identify BGCs in genomic data and predict their chemical products, enabling virtual screening of potentially valuable metabolites before undertaking laborious experimental work [1].

Sustainable Sourcing and Production: To address ecological concerns associated with traditional natural product sourcing, researchers are developing sustainable alternatives including optimized cultivation of producer organisms, microbial fermentation of plant-derived metabolites, and complete synthesis of complex natural products in engineered microbial hosts [1]. These approaches reduce pressure on natural ecosystems while ensuring consistent and scalable production of valuable compounds.

Figure 3: Integrated Natural Product Discovery Workflow

The systematic exploration of terpenoids, alkaloids, polyketides, and peptides reveals both the remarkable structural diversity of natural products and the underlying biosynthetic logic that generates this chemical space. Within chemical biology and systematics research, these compound classes provide invaluable insights into evolutionary biochemistry while serving as privileged scaffolds for therapeutic development. Contemporary research has transitioned from traditional discovery approaches to integrated platforms that combine genomics, synthetic biology, and computational methods, enabling both the identification of novel structures and the engineering of improved analogs. As these technologies continue to mature, particularly with advances in AI-guided prediction and sustainable bioproduction, natural products will remain essential to addressing emerging health challenges and advancing fundamental understanding of chemical biological systems.

The integration of metabolite-content similarity into taxonomic and systematic research represents a paradigm shift in how scientists classify organisms and understand evolutionary relationships. This approach leverages the fundamental principle that organisms produce characteristic sets of small molecules through evolutionary processes, creating chemical profiles that reflect phylogenetic relationships. While traditional taxonomy has relied heavily on morphological characteristics and, more recently, genomic data, metabolite profiling offers a complementary perspective that captures functional biochemical adaptations. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundations, methodological frameworks, and practical applications of metabolite-content similarity as a taxonomic marker across plant and microbial kingdoms, with particular relevance to natural products research in chemical biology and drug discovery. The evidence presented demonstrates that chemical classification not only corroborates established phylogenetic relationships but also provides unique insights into functional ecological adaptations and bioactive potential that may not be apparent from genetic data alone.

Metabolite-content similarity as a taxonomic approach operates on the core premise that secondary metabolites—bioactive substances with diverse chemical structures—have evolved in response to ecological selection pressures and thus reflect evolutionary relationships among organisms [10]. Higher plants inhabiting different ecological environments employ distinct combinations of secondary metabolites for adaptation, suggesting that similarity in metabolite content can effectively indicate phylogenetic similarity [10]. This chemical systematics approach has gained significant traction as analytical technologies have advanced to enable comprehensive metabolomic profiling.

The evolutionary rationale for metabolite-based classification stems from the observation that secondary metabolites are often conserved within taxonomic groups while exhibiting sufficient diversity to distinguish between them. These compounds, including alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenolics, serve ecological functions in defense against herbivores, pathogenic microbes, and environmental stressors [11]. Their structural diversity arises from evolutionary processes that make them excellent markers for tracing phylogenetic lineages and adaptations [12].

In the context of natural products research, metabolite-based taxonomy offers practical advantages for drug discovery by creating associations between taxonomic groups and specific bioactivities. As noted by [12], "Through the natural selection process, natural products possess a unique and vast chemical diversity and have been evolved for optimal interactions with biological macromolecules." This establishes a powerful link between chemical classification and bioprospecting efforts.

Methodological Frameworks for Metabolite-Based Classification

Analytical Techniques for Metabolite Profiling

The reliability of metabolite-content similarity as a taxonomic marker depends heavily on the analytical methods employed for metabolite detection and characterization. Multiple complementary techniques provide comprehensive chemical profiles for taxonomic comparisons.

Table 1: Analytical Techniques in Metabolite-Based Taxonomy

| Technique | Application in Chemotaxonomy | Resolution | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Comprehensive profiling of secondary metabolites | High sensitivity for diverse chemical classes | [11] |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Volatile compound analysis, primary metabolism | Excellent for volatile and semi-volatile compounds | [11] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Structural elucidation, quantitative analysis | Non-destructive, provides structural information | [11] |

| UV Spectroscopy | Preliminary screening, compound class determination | Rapid but limited structural information | [11] |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Functional group analysis, chemical fingerprinting | Rapid classification based on functional groups | [11] |

| MALDI-TOF MS | High-throughput profiling, imaging mass spectrometry | Spatial distribution of metabolites | [11] |

Data Processing and Similarity Assessment

The transformation of raw analytical data into meaningful taxonomic information requires specialized computational approaches. A critical first step involves determining structural similarity between metabolites, typically using the Tanimoto coefficient (also known as Jaccard similarity coefficient) [10]. This measure calculates the proportion of molecular features shared by two compounds divided by their union, with values ranging from 0-1 (higher values indicating greater similarity):

[ \text{Tanimoto}_{A,B} = \frac{A \cap B}{A + B - A \cap B} ]

where (A) and (B) represent the molecular features of two metabolites [10]. Empirically, a Tanimoto coefficient value larger than 0.85 indicates highly similar bioactive compounds [10].

For organism classification, plants or microbes are represented as binary vectors indicating presence or absence relationships with structurally similar metabolite groups [10]. This approach compensates for incomplete metabolomics data by focusing on metabolite groups rather than individual compounds. Similarity between organisms is then calculated using binary similarity coefficients, which are transformed into distance measures for clustering analysis [10].

Classification Algorithms

Hierarchical clustering methods, particularly Ward's method, have been successfully applied to classify plants based on metabolite-content similarity, producing clusters consistent with known evolutionary relations [10]. Additional machine learning approaches such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) have been employed to classify plants by economic uses based on metabolite profiles, demonstrating the predictive power of metabolite content for exploring nutritional and medicinal properties [10].

Applications in Plant Taxonomy

Case Study: Classification of 216 Plant Species

A landmark study demonstrating the efficacy of metabolite-content similarity in plant taxonomy involved the successful classification of 216 plants based on known but incomplete metabolite content data [10]. The methodology employed in this research serves as a prototype for metabolite-based taxonomic approaches:

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Species-metabolite relationships were obtained from the KNApSAcK Core Database, containing 109,976 species-metabolite relationships encompassing 22,399 species and 50,897 metabolites [10]

- Molecular Structure Analysis: Structural description files (MOL files) for metabolites were acquired from KNApSAcK and PubChem databases, with atom pair fingerprints generated using the R package ChemmineR [10]

- Structural Similarity Network: Metabolites were clustered using the DPClus network clustering algorithm based on Tanimoto coefficient calculations [10]

- Plant Representation: Plants were represented as binary vectors indicating relations with structurally similar metabolite groups rather than individual metabolites [10]

- Classification: Hierarchical clustering using Ward's method was applied to similarity matrices derived from binary similarity coefficients [10]

Validation: The resulting plant clusters showed remarkable consistency with known evolutionary relations from NCBI taxonomy, despite the incomplete nature of the metabolomics data [10]. This demonstrates that metabolite content possesses significant taxonomic value as a complementary approach to molecular phylogenetic methods.

Chemotaxonomy of Medicinal Plants

Chemotaxonomy has proven particularly valuable in the identification and classification of medicinal plants, where precise authentication is critical for efficacy and safety [11]. The approach relies on the consistent presence of characteristic secondary metabolites within taxonomic groups:

Table 2: Key Secondary Metabolite Classes in Plant Chemotaxonomy

| Metabolite Class | Chemical Characteristics | Taxonomic Utility | Medicinal Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Nitrogen-containing compounds, basic properties | Family-specific distribution (e.g., Papaveraceae) | Analgesic, antimicrobial activities |

| Flavonoids | Polyphenolic structures, 15-carbon skeleton | Species differentiation within genera | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory |

| Terpenoids | Isoprene unit derivatives, diverse structures | Genus and species level discrimination | Anticancer, antimicrobial |

| Phenolic Compounds | Hydroxylated aromatic rings | Chemotype identification | Antioxidant, neuroprotective |

| Plant Peptides | Short amino acid chains | Recent application in taxonomy | Antimicrobial, signaling |

The integration of chemotaxonomy with DNA barcoding and morphological assessment creates a powerful hybrid identification system that enhances accuracy, particularly for commercially processed plant materials where morphological features may be lost [11].

Applications in Microbial Taxonomy

Metabolic Pathway Similarity for Phylogenetic Reconstruction

Comparative analysis of metabolic pathways has emerged as a robust approach for microbial classification. [13] demonstrated that phylogenetic trees could be derived from similarity analysis of metabolic pathways based on enzyme-enzyme relational graphs. This technique defines distance measures between graphs using node similarity (enzymes) and structural relationships, applying these to metabolic pathways such as the Citric Acid Cycle and Glycolysis across different organisms [13].

The resulting phylogenetic trees showed remarkable concordance with established phylogenies while revealing previously unrecognized relationships among organisms [13]. This approach considers complete metabolic processes rather than individual components, potentially providing a more comprehensive view of functional evolution.

microbeMASST: A Taxonomically Informed Metabolomics Tool

The recent development of microbeMASST represents a significant advancement in microbial metabolite-based taxonomy [14]. This taxonomically informed mass spectrometry search tool addresses the critical challenge of limited microbial metabolite annotation in untargeted metabolomics experiments.

Key Features and Capabilities:

- Database of >60,000 microbial monocultures from diverse environments (plants, soils, oceans, humans) [14]

- Categorization according to NCBI taxonomy at multiple taxonomic levels [14]

- Ability to link both known and unknown MS/MS spectra to microbial producers via fragmentation patterns [14]

- Fast Search Tool implementation enabling rapid database queries [14]

Experimental Workflow:

- Microbial cultures are established from target environments

- LC-MS/MS analysis generates metabolic profiles

- MS/MS spectra are searched against the microbeMASST database

- Matching algorithms identify microbial producers of specific metabolites

- Results are visualized in interactive taxonomic trees with statistical support

Validation Studies: microbeMASST successfully connected known microbial metabolites to their producers, including lovastatin exclusively to Aspergillus species and salinosporamide A specifically to Salinispora tropica [14]. The tool also revealed unexpected connections, such as the widespread production of commendamide across multiple bacterial genera [14].

Integration with Systems Biology and Metabolic Modeling

The application of systems biology approaches represents the cutting edge of metabolite-based taxonomy, particularly through the development of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) [15]. These computational models enable the prediction of metabolic capabilities directly from genomic information, creating a bridge between genetic potential and chemical expression.

Metabolic Modeling of Plant-Microbe Interactions

Plant-microbe interactions are fundamentally mediated by metabolites, creating complex exchange networks that systems biology aims to decipher [15]. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) approaches applied to GEMs can predict metabolic interactions between organisms, including host-microbiome relationships [15]. Recent advancements, such as Expression and Thermodynamics Flux (ETFL) models, incorporate protein synthesis constraints and thermodynamic principles to improve prediction accuracy [15].

Challenges in Metabolic Modeling for Taxonomy

Despite promising developments, several challenges remain in fully leveraging metabolic modeling for taxonomic purposes:

- Parameterization difficulty: Substrate uptake rates and kinetic parameters are rarely available for all metabolites [15]

- Macromolecule integration: The focus on small molecules often neglects the taxonomic importance of macromolecular interactions [15]

- Multi-scale complexity: Integrating metabolic models across cellular, tissue, and organism levels presents computational challenges [15]

- Environmental variability: Metabolic responses to different growth conditions complicate standardized classification [15]

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Metabolite-Based Taxonomy

| Resource/Reagent | Application | Key Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| KNApSAcK Database | Plant-metabolite relationship data | 109,976 species-metabolite relationships, 50,897 metabolites | [10] |

| microbeMASST | Microbial metabolite annotation | 60,781 LC-MS/MS files, 541 microbial strains, NCBI taxonomy mapping | [14] |

| PubChem Database | Metabolite structure information | SDF files for structural similarity calculations | [10] |

| ChemmineR (R package) | Chemical similarity analysis | Tanimoto coefficient calculation, structural clustering | [10] |

| DPClus Algorithm | Network clustering | Identification of structurally similar metabolite groups | [10] |

| GNPS Ecosystem | Mass spectrometry data analysis | Spectral matching, molecular networking | [14] |

| AntiSMASH | Biosynthetic gene cluster detection | Prediction of secondary metabolite pathways | [1] |

Metabolite-content similarity has established itself as a robust taxonomic marker that complements traditional morphological and molecular approaches. The evidence from both plant and microbial kingdoms demonstrates that chemical profiles reflect evolutionary relationships while providing unique insights into functional adaptations and ecological niches. The methodological frameworks outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with standardized approaches for implementing metabolite-based classification in diverse taxonomic contexts.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas:

- Integration of multi-omics data: Combining metabolomic, genomic, and transcriptomic data for comprehensive taxonomic assessment [11] [15]

- Artificial intelligence applications: Machine learning and deep learning algorithms for pattern recognition in complex metabolomic datasets [11] [1]

- Expanded reference databases: Continued growth of curated metabolite databases with improved taxonomic annotations [10] [14]

- Standardization efforts: Development of standardized protocols for metabolite-based taxonomy to enable cross-study comparisons [11]

- Field-deployable technologies: Miniaturized mass spectrometry and spectroscopic tools for real-time chemical classification in ecological studies

As these advancements mature, metabolite-content similarity will play an increasingly important role in systematic research, natural product discovery, and understanding evolutionary relationships across the tree of life.

The search for novel bioactive natural products is a cornerstone of pharmaceutical research, particularly in the development of new antibiotics. A central paradigm guiding this discovery process is the observed correlation between taxonomic distance and the diversity of secondary metabolites produced by microorganisms. This paradigm posits that examining phylogenetically distant taxa, such as new genera or families, significantly increases the likelihood of discovering novel chemical scaffolds compared to further sampling within well-studied genera. This whitepaper examines the robust evidence supporting this taxonomy paradigm, details the experimental methodologies that validate it, and discusses its critical implications for future natural product discovery and microbial systematics.

Quantitative Evidence for the Taxonomy Paradigm

Key Evidence from Systematic Metabolite Surveys

A large-scale systematic metabolite survey of the bacterial order Myxococcales provides compelling quantitative evidence for the taxonomy paradigm. The study, which analyzed approximately 2,300 bacterial strains using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), found a clear correlation between taxonomic distance and the production of distinct secondary metabolite families [16].

Table 1: Distribution of Known Metabolites in Myxococcales

| Taxonomic Level | Finding | Implication for Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Genus Level | Existence of unique or highly genus-specific compound families [16] | Chances of discovering novel metabolites are greater by examining strains from new genera. |

| Sub-genus Level | Clustering based on known metabolites allocated most data sets into genus-featuring clades [16] | Significant inter-genera variations exist in the secondary metabolome. |

| Species Level | General tendency toward species-typical compounds, though less distinct than genus-level separation [16] | Species-level discovery is feasible but may offer diminishing returns compared to genus-level exploration. |

The analysis revealed that a striking subset of compound families was either unique to a single genus or demonstrated high genus specificity. This pattern provides strong evidence for the existence of distinct chemotypes corresponding to taxonomic divisions [16]. The findings further support the strategy of prioritizing the exploration of new genera to increase the probability of finding novel natural product scaffolds, a approach that has already led to the discovery of new structures like rowithocin, which features an uncommon phosphorylated polyketide scaffold [16].

Supporting Evidence from Other Taxonomic Groups

The correlation between taxonomy and secondary metabolite production is not confined to myxobacteria. Studies on the fungal genus Aspergillus have similarly demonstrated that secondary metabolite profiles are highly species-specific and can be used effectively in species recognition and classification [17].

Table 2: Supporting Evidence from Diverse Taxonomic Groups

| Organism Group | Evidence for Taxonomy-Chemistry Correlation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus Section Nigri | Specific secondary metabolite profiles characterise each species; "chemoconsistency" is pronounced. | [17] |

| Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) | Significant variation in secondary metabolites (flavonoids, tannins) among different accessions, influenced by environmental factors. | [18] |

| Lactobacillaceae Family | Genome mining reveals a richness of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), with most having unknown functions, indicating vast unexplored chemical diversity. | [19] |

In Aspergillus, the classification based on morphological, physiological, and chemical features shows excellent agreement with phylogenetic groupings based on β-tubulin sequencing, illustrating a strong link between evolutionary history and chemical capacity [17]. This "chemophylogeny" provides a powerful framework for targeting taxonomic groups with high probabilities of yielding novel chemistries.

Experimental Methodologies for Validating the Paradigm

Standardized Workflow for Metabolite Correlation Studies

Establishing a robust correlation between taxonomy and metabolite production requires a standardized, high-throughput workflow from strain selection to data analysis. The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental protocol based on the myxobacteria study [16].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for metabolite-taxonomy correlation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Strain Selection and Cultivation

- Strain Collection: Select a diverse set of microbial strains that achieve high coverage of the target taxonomy. For myxobacteria, this involved ~2,300 strains representing a wide phylogenetic breadth within the order [16].

- Cultivation: Grow all strains in empirically optimized, genus-typical cultivation media to ensure expression of secondary metabolite pathways. Standardize protocols for temperature, aeration, and incubation time to minimize technical variation [16].

Metabolite Extraction and Analysis

- Extraction: Process bacterial cultures according to standardized protocols for metabolite extraction, using consistent solvent systems, volumes, and drying procedures [16].

- LC-MS Analysis: Analyze all extracts using uniform Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) conditions. High-resolution mass spectrometry is critical for accurate mass determination and initial structural characterization [16].

Data Processing and Analysis

- Metabolite Annotation: Process LC-MS data sets to examine for known compounds based on accurate mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), retention time, and isotope pattern fits to reference data from purified compounds [16].

- Creation of Distribution Matrix: Construct a compound distribution matrix comparing compound family occurrence against taxonomic classification (suborder, family, genus) [16].

- Statistical Clustering: Perform hierarchical clustering of individual, blinded data sets based on their metabolite production profiles to determine if they self-organize into taxonomically relevant clades without prior classification input [16].

Genomic Foundations of the Taxonomy Paradigm

Genome Mining and Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Diversity

The taxonomy paradigm is strongly supported by genomic evidence, as the genetic potential for secondary metabolite production is encoded within Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs). Comprehensive analysis of bacterial genomes reveals that phylogenetically distinct organisms harbor unique BGCs, suggesting they can produce novel compounds [20].

Advanced computational platforms like PRISM 4 enable the prediction of chemical structures from genomic sequences, facilitating the targeted discovery of novel antibiotics. PRISM 4 uses 1,772 hidden Markov models (HMMs) and implements 618 in silico tailoring reactions to predict the structures of 16 different classes of secondary metabolites [20]. When applied to 3,759 bacterial genomes, PRISM 4 predicted thousands of encoded antibiotics, with a particular abundance of novel BGCs in phylogenetically distinct bacterial phyla such as Desulfobacterota, Spirochaetota, and Campylobacterota [20]. This genomic-based approach corroborates the metabolite survey findings and provides a powerful tool for prioritizing microbial taxa for experimental investigation.

From Genotype to Chemotype: Bridging the Gap

A significant challenge in natural product research is the gap between the genomic capacity of a strain (genotype) and the metabolites observed under laboratory cultivation conditions (chemotype) [16]. This disconnect underscores the importance of complementing genomic predictions with empirical metabolite profiling, as exemplified by the integrated workflow in Section 3.

The correlation between taxonomic distance and BGC diversity suggests that exploring new genera provides access not only to new BGC sequences but also to novel enzymatic transformations and biosynthetic logic, which are the foundations of chemical diversity [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Metabolite-Taxonomy Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Research | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Optimized Cultivation Media | To support the growth of diverse microbial taxa and elicit the production of secondary metabolites. | Empirically developed for specific taxonomic groups; composition varies by genus [16]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | For high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of metabolite extracts. | High purity (e.g., ≥99.9%) to minimize background noise and ion suppression [16]. |

| Metabolite Standard Libraries | For dereplication of known compounds via comparison of m/z, retention time, and isotope patterns. | Curated in-house databases containing characterized metabolites from the studied taxa [16]. |

| Genomic DNA Extraction Kits | To obtain high-quality DNA for sequencing and BGC analysis. | Must be suitable for the specific microbial group (e.g., Gram-negative bacteria, fungi). |

| PCR Reagents for BGC Amplification | To amplify and sequence specific biosynthetic gene clusters of interest. | Include high-fidelity DNA polymerases and cluster-specific primers [20]. |

| Bioinformatics Software (e.g., PRISM 4) | To predict chemical structures of secondary metabolites from genomic sequences. | Utilizes HMMs and reaction rules for in silico pathway reconstruction [20]. |

| N,N'-Bis(8-aminooctyl)-1,8-octanediamine | N,N'-Bis(8-aminooctyl)-1,8-octanediamine, CAS:15518-46-4, MF:C24H54N4, MW:398.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Leucomycin A4 | Leucomycin A4, CAS:18361-46-1, MF:C41H67NO15, MW:814.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The taxonomy paradigm—that a strong correlation exists between taxonomic distance and secondary metabolite diversity—is robustly supported by both large-scale empirical metabolomic studies and comprehensive genomic analyses. This paradigm provides a powerful strategic framework for maximizing the efficiency and success of natural product discovery campaigns. By prioritizing the exploration of phylogenetically novel and underexplored microbial genera, researchers can significantly increase their chances of discovering unprecedented chemical scaffolds with potential bioactivities. As genomic and metabolomic technologies continue to advance, their integrated application within this taxonomic framework will undoubtedly continue to reveal the vast, untapped chemical potential of the microbial world, fueling the next generation of therapeutic agents.

In the fields of chemical biology and systematics, the evolutionary history of organisms, or phylogeny, provides a powerful framework for understanding and predicting the structural diversity of natural products. Natural products, also known as secondary metabolites, are chemical compounds produced by organisms such as bacteria, fungi, and plants that often possess potent biological activities. These molecules have historically been an essential source for drug discovery, with natural products and their derivatives accounting for a significant proportion of newly approved drugs, including first-in-class therapeutics [21] [12]. The structural classes of these compounds—including polyketides, nonribosomal peptides, terpenoids, and alkaloids—are not randomly distributed across the tree of life but are instead linked to the evolutionary histories of their producing organisms [22].

The core thesis of this whitepaper is that phylogenetic relationships are highly informative for delineating the architecture and function of genes involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis. By applying molecular phylogenetics to the study of biogenic pathways, researchers can create predictive models that connect taxonomic identity with chemical structural classes. This approach, often termed phylogenomics, has been enabled by the vast increase in publicly available genomic sequence data and sophisticated bioinformatic tools [22]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the methodologies, applications, and experimental protocols for mapping structural classes to biological sources, offering researchers and drug development professionals a comprehensive resource for leveraging phylogeny in natural product discovery.

Fundamental Concepts: Phylogenetics and Biosynthetic Logic

Principles of Molecular Phylogenetics

Phylogenetics is the study of evolutionary relatedness among groups of organisms based on molecular sequence data. The results of these analyses are typically represented as phylogenetic trees—diagrams whose branches represent evolutionary lineages and whose nodes represent inferred speciation events or gene duplication events [23] [24]. Two fundamental concepts in molecular phylogenetics are critical for natural product research:

- Orthologs vs. Paralogs: Orthologs are homologs produced by speciation (divergence of species), while paralogs are produced by gene duplication within a genome. Using orthologs is essential for inferring species relationships, as the use of paralogs can lead to incorrect phylogenetic inferences due to incomplete sampling of duplicated gene families [23].

- Rooted vs. Unrooted Trees: A rooted tree has a designated node representing the most common ancestor of all entities in the tree, providing directionality to evolutionary relationships. An unrooted tree shows relatedness without assumptions about ancestry, with the most probable root often placed at the midpoint of the longest path between taxa [23].

Molecular phylogenies are inferred using various optimality criteria, including maximum parsimony (favoring the tree requiring the fewest evolutionary changes), maximum likelihood (seeking the tree with the highest probability given the sequence data and an evolutionary model), and Bayesian inference (which incorporates prior knowledge to estimate the posterior probability of trees) [24].

Biosynthetic Logic of Major Natural Product Classes

The structural diversity of natural products arises from specific, evolutionarily conserved biosynthetic logic. Two of the most extensively studied enzyme systems are polyketide synthases (PKSs) and nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), which are responsible for assembling many clinically valuable microbial metabolites [22].

- Polyketide Synthases (PKS): Polyketides are polymers of acetate and other simple carboxylic acids that display remarkable structural diversity due to their combinatorial assembly process. PKSs are multienzyme complexes that sequentially construct polyketides in an assembly-line fashion. They are broadly categorized into three types (I-III), with type I PKSs being particularly diverse and often modular in architecture [22].

- Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS): NRPSs assemble structurally complex peptides from amino acid building blocks without direct RNA template guidance. Similar to PKSs, they function as modular assembly lines, with each module typically consisting of condensation (C), adenylation (A), and thiolation (T) domains responsible for activating, incorporating, and carrying the growing peptide chain [22].

Table 1: Major Natural Product Biosynthetic Systems and Their Characteristics

| Biosynthetic System | Building Blocks | Key Enzymes/Domains | Representative Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyketide Synthases (PKS) | Carboxylic acids (e.g., acetate, malonate) | Ketosynthase (KS), Acyltransferase (AT), Ketoreductase (KR) | Erythromycin, Tetracycline [22] |

| Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS) | Amino acids | Condensation (C), Adenylation (A), Thiolation (T) | Cyclosporine, Penicillin [22] |

| Hybrid PKS-NRPS | Carboxylic acids & Amino acids | KS, AT, C, A, T | Rapamycin, Epothilone [12] |

The evolutionary history of these biosynthetic systems is complex, involving processes such as gene duplication, recombination, and horizontal gene transfer (HGT), which collectively generate new structural diversity [22].

Methodologies: Integrating Phylogenetics and Pathway Analysis

Phylogenetic Analysis of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

The genes encoding natural product biosynthetic pathways are typically organized in clusters in microbial genomes. Phylogenetic analysis of specific domains within these clusters can reveal relationships that predict structural features of the final metabolic product.

- Ketosynthase (KS) Domain Phylogeny: KS domains are the most conserved domains in PKSs and form highly predictive clades in phylogenetic trees. Different KS clades correspond to distinct enzyme architectures or biochemical functions. For example, a specific KS clade comprises iterative type I PKSs that produce enediynes, a class of potent anticancer agents including calicheamicin. Finer phylogenetic resolution within this clade can even distinguish between genes producing 9- or 10-membered core enediyne ring structures [22].

- Adenylation (A) Domain Phylogeny in NRPS: A domains are responsible for selecting and activating specific amino acid building blocks in NRPS assembly lines. The phylogeny of A domains can be used to predict the substrate specificity of each module, thereby informing predictions about the amino acid sequence of the resulting nonribosomal peptide [22].

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for conducting a phylogenetic analysis of a biosynthetic gene cluster to map structural classes to biological sources.

Metabolic Pathway Alignment and Functional Module Mapping

Beyond single genes or domains, entire metabolic pathways can be compared across organisms to infer phylogenetic relationships. A method called MMAL (Multiple Metabolic Pathway Alignment) transforms the alignment of multiple pathways into constructing a union graph, identifies functional modules within this graph, and builds mappings between these modules [25]. The similarity between pathways is then computed by comparing the mapped functional modules, and phylogenetic relationships are inferred from these similarities.

Experimental results demonstrate that this approach can correctly categorize organisms into main groups with specific metabolic characteristics. For instance, analysis of 16 organisms showed that the two archaea included in the study (Archaeoglobus fulgidus and Methanocaldococcus jannaschii) consistently formed a distinct group, suggesting that archaea have particular metabolic pathway characteristics different from other species [25]. This methodology reveals that pathway topologies are the result of a compromise between phylogenetic information inherited from a common ancestor and evolutionary pressures that cause more rapid shifts in metabolic structure [26].

Taxon Sampling and Robustness Considerations

Judicious taxon sampling is critical in phylogenetic analysis, as poor sampling may result in incorrect inferences. Theoretical causes for inaccuracy include long branch attraction, where non-related branches are incorrectly grouped by shared nucleotide sites [24]. Research has shown that, when working with a fixed number of total nucleotide sites, sampling fewer taxa with more sites (genes) per taxon often yields higher bootstrapping replicability and accuracy than sampling more taxa with fewer sites per taxon [24]. However, increasing the number of genes compared per taxon can be challenging for uncommonly sampled organisms due to unbalanced genomic databases.

Table 2: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Phylogenetic Analysis of Natural Product Biosynthesis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Natural Product Research | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaPDoS (Natural Product Domain Seeker) | Classifies KS and C domains using phylogenetic logic | Predicts enzyme architecture and biochemical function from sequence data [22] | |

| antiSMASH | Identifies secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters | In silico analysis of gene cluster architecture and potential products [22] | |

| IsoRankN | Global multiple-network alignment tool | Used for phylogenetic reconstruction from multiple metabolic pathways [25] | |

| PHYLIP | Software package for inferring phylogenetic trees | Builds phylogenetic trees from distance matrices (e.g., using neighbor-joining) [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Building a Reliable Phylogenetic Tree for Biosynthetic Genes

This protocol outlines the key steps for constructing a phylogenetic tree from PKS KS or NRPS C domains to predict structural features of the resulting natural products [22].

Sequence Acquisition and Curation:

- Retrieve amino acid sequences of target biosynthetic domains (e.g., KS domains for PKS, C domains for NRPS) from databases or sequencing projects.

- Manually inspect sequences for completeness and the presence of key catalytic residues. Exclude fragments or sequences with obvious errors.

Multiple Sequence Alignment:

- Use alignment software such as MUSCLE or ClustalW to create a multiple sequence alignment.

- Visually inspect the alignment and manually refine if necessary to ensure proper alignment of conserved motifs.

Phylogenetic Tree Inference:

- Select an evolutionary model that best fits the alignment data using model-testing software (e.g., ProtTest for protein sequences).

- Construct an initial tree using a fast method such as Neighbor-Joining.

- Perform rigorous phylogenetic analysis using Maximum Likelihood (e.g., with RAxML) or Bayesian inference (e.g., with MrBayes).

- Execute multiple independent runs to assess convergence.

Tree Assessment and Interpretation:

- Evaluate branch support using bootstrap analysis (for Maximum Likelihood) or posterior probabilities (for Bayesian inference).

- Map known functional and structural data from characterized gene clusters onto the tree to identify clades associated with specific architectural features or product structural classes.

Protocol: Phylogenetic Analysis of Entire Metabolic Pathways

This protocol describes a method for inferring phylogenetic relationships by aligning multiple metabolic pathways based on topological similarities, as exemplified by the MMAL framework [25].

Data Retrieval and Pathway Definition:

- Retrieve metabolic pathway data for a set of target organisms from the KEGG database.

- Define the set of common metabolic pathways to be analyzed across all organisms.

Union Graph Construction and Module Mapping:

- Transform the alignment of multiple metabolic pathways into the construction of a union graph of these pathways.

- Cluster the nodes in the union graph to identify functional modules within the pathways.

- Build mappings between the functional modules of different organisms' pathways.

Distance Matrix Calculation and Tree Building:

- Compute the similarity between pathways by comparing the mapped functional modules.

- Produce a distance matrix for the set of organisms based on the pathway topology similarities.

- Build a phylogenetic tree from the distance matrix using a neighbor-joining algorithm as implemented in software such as PHYLIP.

Tree Validation and Comparison:

- Compare the resulting pathway-based phylogenetic tree to a reference tree (e.g., based on 16S rRNA) using software such as COUSINS to assess similarity based on cousin pairs.

- Analyze the tree to identify clusters that reflect both phylogenetic relationships and specific metabolic characteristics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Phylogenetically-Guided Natural Product Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Purpose | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG Database | Reference database for metabolic pathways and genes | Used to retrieve organism-specific pathway data for comparative analysis [25] |

| 16S rRNA Sequence Data | Molecular marker for constructing reference organismal phylogenies | Serves as a benchmark for evaluating metabolic pathway-based trees [25] |

| PHYLIP Software Package | Infers phylogenetic trees from sequence or distance data | Used with neighbor-joining algorithm to build trees from pathway-based distance matrices [25] |

| NaPDoS Web Tool | Phylogenetically classifies KS and C domains from sequence data | Predicts biosynthetic function and links sequences to structural classes [22] |

| antiSMASH | Identifies and annotates biosynthetic gene clusters in genomic data | Provides first-pass in silico analysis of natural product potential [22] |

| Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) | Community resource for sharing and curating mass spectrometry data | Aids in metabolite identification and cross-referencing structural data [21] |

The integration of phylogenetics with the study of biogenic pathways represents a powerful paradigm shift in natural product research. By applying evolutionary thinking to the genes, domains, and pathways responsible for secondary metabolite biosynthesis, researchers can create predictive models that efficiently link biological sources to structural classes. This approach adds a layer of insight to traditional phyletic reconstruction from a metabolic standpoint and offers a rational strategy for prioritizing organisms and gene clusters for drug discovery efforts [25] [22].

Future advancements in this field will be driven by the increasing availability of genomic data from diverse taxa, improvements in algorithms for phylogenetic inference and pathway comparison, and the development of more sophisticated bioinformatic tools that integrate phylogenetic prediction with structural elucidation. As these methodologies mature, phylogenetically guided discovery will continue to enhance our understanding of natural product evolution and accelerate the identification of novel bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential.

Chemosystematics, also referred to as chemotaxonomy, represents a critical interdisciplinary field that utilizes the chemical constituents of organisms to elucidate taxonomic relationships and evolutionary pathways [27] [28]. Originally an unwritten knowledge system for distinguishing useful from harmful plants, it has evolved into a formalized science that integrates chemistry, phylogenetics, and natural product research [27]. This whitepaper delineates the theoretical foundations of chemosystematics, highlighting how advancements in analytical technologies, particularly metabolomics, have solidified the correlation between an organism's chemical profile and its evolutionary history [29] [30]. The core thesis is that secondary metabolites, produced through evolutionarily conserved biosynthetic pathways, provide a robust chemical record that complements morphological and molecular data, thereby offering invaluable insights for systematic biology and modern drug discovery [12] [30].

The fundamental principle of chemosystematics is that the presence, absence, or proportional distribution of specific chemical compounds within organisms can reveal phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary divergence [27] [28]. These chemical profiles, especially those of secondary metabolites, are the phenotypic expression of deep-seated genetic and enzymatic processes that are subject to natural selection [29]. Consequently, the metabolic architecture of a plant is more closely linked to its genotype than many classic morphological traits [29]. Historically, this knowledge was applied informally; however, the field has been progressively formalized, with useful, harmful, and inactive chemical constituents from relevant taxa now identified and recorded [27].

The close relationship between chemical profiles and evolutionary relationships is evidenced by the high degree of concordance between established taxonomy and chemotaxonomy at the genus level [30]. This positions chemosystematics as a powerful bridge between evolution and chemistry, providing a chemical window into the evolutionary history of life.

The Evolutionary and Biochemical Basis

Secondary Metabolites as Evolutionary Endpoints

Through the process of natural selection, natural products possess a unique and vast chemical diversity and have been optimized for specific interactions with biological macromolecules [12]. These secondary metabolites are not merely metabolic byproducts but are crucial for environmental interactions, such as defending against fungi, bacteria, and viruses [30]. Their structural diversity enables them to interact optimally with proteins and other biological targets, a property that is exploited both by the producing organisms and, subsequently, by humans for drug discovery [12].

The structural complexity of natural products often makes them highly effective in modulating challenging biological processes, such as protein-protein interactions [12]. For instance, macrocyclic natural products like cyclosporine A and rapamycin create composite surfaces with their binding proteins to facilitate specific macromolecular interactions, a success that underscores their evolutionary refinement [12].

Chemotaxonomic Patterns in the Plant Kingdom

Large-scale analyses of the known phytochemical space have revealed distinct taxonomic patterns. The distribution of secondary metabolites across the plant kingdom is not random but is strongly influenced by evolutionary ancestry [30]. Research has identified hotspot taxonomic clades rich in medicinal plants and characterized secondary metabolites, alongside other clades that remain chemically under-explored [30]. This phylogenetic conservation occurs because secondary metabolites are typically produced by conserved metabolic routes [30]. The resulting chemical relatedness among species allows for the construction of a chemotaxonomy—a classification system based on chemical similarity—which shows a significant concordance with modern phylogenetic taxonomy [30].

Table 1: Key Categories of Secondary Metabolites and Their Chemotaxonomic Significance

| Metabolite Class | Chemotaxonomic Utility | Research Techniques | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolics | High value for differentiating dicotyledons and monocotyledons [28]. | Spectrophotometry, Chromatography [28]. | Flavone glycosides in Citrus species [29]. |

| Non-Protein Amino Acids & Amines | Provide information from chemotaxonomic to severely practical applications [27]. | Chromatography, Electrophoresis [28]. | Specific amines in the Tephrosieae tribe [28]. |

| Alkaloids | "Privileged" scaffolds with distribution often limited to specific families or genera [12]. | LC-MS, NMR [29]. | Sugar-shaped alkaloids acting as glycosidase inhibitors [28]. |

| Terpenoids | Useful markers at familial and generic levels, contributing to ecological interactions [28]. | GC-MS, LC-MS [29]. | --- |

Analytical Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The evolution of chemosystematics has been inextricably linked to advancements in analytical instrumentation. The field has progressed from simple chemical tests to sophisticated metabolic profiling, or metabolomics, which captures a comprehensive analysis of small molecule metabolites [27] [29].

Metabolomic Workflow for Chemotaxonomic Classification

A typical workflow for a chemotaxonomic study using metabolomics is outlined below. This protocol is adapted from studies on closely-related Citrus fruits used in Traditional Chinese Medicines [29].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Plant Material Selection: Identify and collect biological material from species of interest across defined taxonomic groups, developmental stages, or environmental conditions. For Citrus studies, this involved sampling fruits at different ripening stages [29].

- Extraction: Homogenize plant tissue and extract metabolites using a suitable solvent system (e.g., methanol-water). Centrifuge to remove particulate matter and pass the supernatant through a solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridge if necessary for cleanup [29].

2. Instrumental Analysis via UPLC-Q-TOF-MS:

- Chromatographic Separation: Employ Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) with a reversed-phase column. A typical mobile phase consists of methanol and 0.1% acetic acid in water, using a gradient elution to achieve optimal separation of metabolites [29].

- Mass Spectrometric Detection: Utilize a Quadrupole-Time-of-Flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometer for accurate mass detection. Optimized parameters should include [29]:

- Capillary Voltage: 3.0 kV (positive mode) / 3.5 kV (negative mode)

- Desolvation Gas Flow: 800 L/h

- Desolvation Temperature: 400 °C

- Nebulizer Pressure: 40 psi

- Quality Control (QC): Prepare a pooled QC sample by combining an aliquot of every sample. Run multiple QC samples at the beginning of the sequence and intersperse them after every five analytical samples to monitor system stability [29].

3. Data Processing and Metabolite Identification:

- Data Extraction: Process raw MS data using software to perform peak picking, alignment, and deconvolution, generating a data matrix of features (mass-retention time pairs) and their intensities.

- Metabolite Annotation: Identify metabolites by matching accurate mass and MS/MS fragmentation spectra against authentic standards or curated natural product databases [29]. For unknown compounds, use in-silico fragmentation tools and consider subsequent isolation and NMR spectroscopy for definitive structural elucidation [21].

4. Statistical and Chemometric Analysis:

- Multivariate Analysis: Import the normalized data matrix into statistical software. Use unsupervised methods like Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to observe natural clustering. Apply supervised methods like Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) to identify metabolites most responsible for the discrimination between predefined groups [29].

- Biomarker Identification: From the OPLS-DA model, identify potential chemotaxonomic markers based on their variable importance in projection (VIP) scores and confirm significance with univariate statistics [29].

- Pathway Analysis: Input the identified discriminant metabolites into pathway analysis tools (e.g., MetaboAnalyst) to visualize their positions in biochemical pathways and interpret the metabolic basis for the observed classification [29].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolomics-Based Chemosystematics

| Item/Reagent | Function in Protocol | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| UPLC-Q-TOF-MS System | High-resolution separation and accurate mass detection of complex metabolite extracts. | Enables untargeted profiling and preliminary identification of hundreds of compounds [29]. |

| Methanol & Acetic Acid | Components of the mobile phase for chromatographic separation. | Methanol and 0.1% acetic acid provide good peak shape and separation for diverse metabolites [29]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Clean-up and pre-concentration of plant extracts to remove interfering compounds. | Used prior to injection to protect the chromatographic column and improve data quality. |

| Authentic Chemical Standards | Validation and absolute quantification of identified metabolites. | Critical for unambiguous annotation of compounds like specific flavone glycosides [29]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O, CD₃OD) | Solvents for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. | Used for definitive de novo structure elucidation of novel compounds [21]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pooled Sample | Monitors instrument stability and performance throughout the analytical sequence. | A pool of all study samples analyzed repeatedly; RSD values for peak areas should be <10% [29]. |

| Kasugamycin hydrochloride | Kasugamycin hydrochloride, CAS:19408-46-9, MF:C14H26ClN3O9, MW:415.82 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Curvulin | Curvulin, CAS:19054-27-4, MF:C12H14O5, MW:238.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Chemical Biology and Drug Discovery

The theoretical basis of chemosystematics has profound practical implications, particularly in the discovery and development of new therapeutic agents.

Navigating Chemical Space for Drug Leads

Natural products occupy a unique and vast region of chemical space, distinct from that covered by synthetic combinatorial libraries [12]. This diversity is a direct result of evolutionary selection for biological activity. Analysis of the known phytochemical space reveals that while medicinal plants have been a primary source of drugs, non-medicinal plants also contain numerous bioactive compounds and do not occupy distinct chemical regions [30]. This suggests that chemosystematics can guide the targeted exploration of under-studied taxonomic clades for new drug leads [30]. Historically, natural products and their derivatives have been a major source of new pharmacotherapies, especially for cancer and infectious diseases, with 13 natural product-derived drugs approved worldwide between 2005 and 2007 alone [12].

From Natural Product to Probe and Drug

Numerous natural products have served as essential molecular probes to decipher biological pathways, thereby validating their utility in chemical biology and their inherent bioactivity [12].

- TNP-470: A synthetic analogue of fumagillin, which was identified as a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Its target, the type 2 methionine aminopeptidase (MetAP2), was discovered through a combination of chemical modification and site-directed mutagenesis, revealing a new potential therapeutic target for cancer [12].

- FTY720: A synthetic analogue of myriocin, this immunosuppressant is phosphorylated in vivo and acts as an agonist for sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptors. This reverse pharmacology approach provided novel insights into the S1P pathway and its therapeutic relevance [12].

- Diazonamide A: This marine natural product was found to induce M-phase arrest, not by binding tubulin, but through an unexpected interaction with the mitochondrial enzyme ornithine delta-amino transferase (OAT), revealing a paradoxical role for OAT in cell division [12].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual journey from a naturally occurring chemotaxonomic marker to a tool for basic research or a clinical therapeutic.

Chemosystematics provides a powerful theoretical and practical framework that bridges evolutionary biology and chemistry. Its core premise—that the chemical constituents of an organism are a reflection of its evolutionary history and genetic makeup—has been validated by modern metabolomic technologies and large-scale analyses of the phytochemical kingdom [29] [30]. The field has evolved from a descriptive cataloguing of compounds to a sophisticated science that can predict taxonomic relationships, reveal biosynthetic pathways, and guide the discovery of new bioactive molecules [27] [12]. As analytical techniques continue to advance, allowing for deeper and more comprehensive metabolic profiling, the integration of chemosystematic data with genomic and transcriptomic information will offer an increasingly holistic view of organismal phylogeny and function. For researchers in chemical biology and drug development, the chemosystematic approach offers a rational, evolutionarily-grounded strategy for navigating the vast, untapped potential of natural products, ensuring its continued relevance in the discovery of new therapeutic agents and biological probes.

Toolkit for the Modern Explorer: Integrating Omics, Synthesis, and Bioengineering

Genome Mining and Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC) Analysis for Prioritizing Discovery

The field of natural product discovery has been revolutionized by the advent of genome mining, a computational approach that leverages the growing wealth of genomic data to identify biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). These clusters are chromosomal loci containing genes that encode the biosynthesis of specialized metabolites, which are not essential for growth but provide competitive advantages to producing organisms [31]. Early natural product discovery relied heavily on phenotypic screening of fermentation broths, an approach hampered by high rediscovery rates and low throughput [31]. Genome mining has emerged as a powerful alternative, enabling systematic exploration of an organism's metabolic potential through in silico analysis [31] [32].

BGCs typically contain core biosynthetic genes (such as polyketide synthases [PKS] and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases [NRPS]) that determine the structural scaffold of the metabolite, along with tailoring enzymes (e.g., methyltransferases, oxidoreductases) that modify the core structure, regulatory genes, and transport-related genes [33] [31]. The fundamental premise of genome mining is that identifying and analyzing these clusters can predict an organism's capacity to produce specific secondary metabolites, thus enabling prioritization of strains for further experimental investigation [32]. This approach is particularly valuable for uncovering "cryptic" BGCs—those not expressed under standard laboratory conditions—which represent a vast reservoir of novel chemical diversity [32].

Within chemical biology and systematics research, genome mining provides a phylogenetic framework for understanding metabolic capability across taxa. Large-scale comparative analyses reveal how BGCs are distributed across related species, informing both evolutionary studies and targeted discovery efforts [31]. For drug development professionals, this approach offers a rational strategy to prioritize the most promising BGCs for experimental characterization, streamlining the natural product discovery pipeline.

Core Methodologies and Workflows

Computational Identification of BGCs