Natural Product-Based Drug Design and Scaffold Hopping: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of natural product-based drug design, with a specific focus on the strategy of scaffold hopping.

Natural Product-Based Drug Design and Scaffold Hopping: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of natural product-based drug design, with a specific focus on the strategy of scaffold hopping. It explores the foundational role of natural products as biologically prevalidated starting points for drug discovery, detailing the principles of scaffold hopping as defined by its key objective: retaining biological activity while altering the core molecular structure. The content covers a spectrum of methodological approaches, from traditional bioisosteric replacements and pharmacophore-based searches to modern, AI-driven generative models. It further addresses common challenges in the field, such as balancing structural novelty with maintained activity and navigating intellectual property, and presents validation frameworks through case studies and comparative analyses of different techniques. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes historical context, current state-of-the-art technologies, and future directions, offering a practical guide for leveraging natural product-inspired design to discover novel therapeutic candidates with improved properties.

The Unparalleled Role of Natural Products as a Foundation for Drug Discovery

Why Natural Products? Historical Success and Inherent Bioactivity

Natural products (NPs) are chemical compounds derived from natural sources such as plants, microorganisms, marine organisms, and fungi. These molecules have served as a major source of chemically novel, bioactive therapeutics throughout human history and continue to play a pivotal role in modern drug discovery [1] [2]. Their structural diversity and evolutionary refinement make them indispensable for tackling complex medical challenges, particularly for cancer and infectious diseases [3] [4].

The historical use of natural products dates back to ancient civilizations, with the earliest records depicted on clay tablets in cuneiform from Mesopotamia (2600 B.C.) documenting oils from Cupressus sempervirens (Cypress) and Commiphora species (myrrh) for treating coughs, colds, and inflammation [1]. The continued relevance of these natural compounds in modern medicine underscores their inherent bioactivity and therapeutic value, validated by both traditional use and contemporary scientific research [1] [5].

Historical Success of Natural Products

Traditional Medicine and Early Discoveries

Traditional medicinal practices have formed the foundation of most early medicines, with subsequent clinical, pharmacological, and chemical studies validating their efficacy [1]. Ancient records including the Ebers Papyrus (2900 B.C.), Chinese Materia Medica (1100 B.C.), and the works of Greek physician Dioscorides (100 A.D.) documented hundreds of plant-based drugs that established the foundation for modern pharmacotherapy [1].

Probably the most famous example is the development of acetylsalicyclic acid (aspirin) derived from the natural product salicin isolated from the bark of the willow tree Salix alba L. [1]. Similarly, investigation of Papaver somniferum L. (opium poppy) resulted in the isolation of several alkaloids including morphine, first reported in 1803, which remains a commercially important analgesic drug [1].

Natural Products in Modern Drug Discovery

Natural products and their structural analogues have historically made a major contribution to pharmacotherapy, especially for cancer and infectious diseases [4]. Despite a decline in their pursuit by the pharmaceutical industry from the 1990s onwards, recent technological developments have revitalized interest in natural product-based drug discovery [3] [4].

Table 1: Historically Significant Natural Product-Derived Drugs

| Natural Product | Source Organism | Therapeutic Application | Discovery Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salicin | Willow tree (Salix alba L.) | Anti-inflammatory (precursor to aspirin) | Ancient use, isolated 1828 |

| Morphine | Opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) | Analgesic | Isolated 1803 |

| Artemisinin | Sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua) | Antimalarial | Discovered 1972 |

| Paclitaxel | Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia) | Anticancer | Discovered 1971 |

| Teixobactin | Bacterium (Eleftheria terrae) | Antibiotic | Discovered 2015 |

Natural products continue to provide unique structural diversity in comparison to standard combinatorial chemistry, which presents opportunities for discovering novel low molecular weight lead compounds [1]. With less than 10% of the world's biodiversity evaluated for potential biological activity, numerous useful natural lead compounds await discovery [1].

Inherent Bioactivity of Natural Products

Evolutionary Advantages

Natural products distinguish themselves from synthetic libraries through their elevated molecular complexity, including higher proportions of sp3-hybridized carbon atoms, increased oxygenation, and decreased halogen and nitrogen content [2]. This chemical richness is coupled with rigid molecular frameworks and lower lipophilicity, traits that facilitate favorable interactions with biological targets, particularly those elusive to synthetic small molecules [2].

What sets NPs apart most profoundly is their evolutionary purpose [6]. These molecules function as defense chemicals, signaling agents, and ecological mediators, fine-tuned for optimal interactions with living systems through millions of years of evolutionary refinement [6] [2]. This natural selection has endowed NPs with mechanisms of action that exploit biological vulnerabilities, particularly in pathogens and cancer cells [2].

Diverse Biological Functions

Natural products possess several innate functions, including the ability to allosterically alter the catalytic activity of enzymes, promote or disrupt macromolecular interactions, act as chemical messengers between cells, participate in inter-kingdom signaling, and serve as toxins for defense [6]. They can even carry out some protein-like functions of their own [6].

The biochemical diversity of natural products presents both a challenge and source of inspiration for biologists and chemists across the globe [6]. This diversity enables them to target specific pathways implicated in disease processes, offering tailored therapeutic strategies [5]. Moreover, the synergy observed within natural extracts—where multiple bioactive compounds act collaboratively—enhances their overall efficacy and broadens their therapeutic potential [5].

Table 2: Innate Functions of Natural Products in Producing Organisms

| Function | Mechanism | Example Natural Products |

|---|---|---|

| Defense | Deter herbivory through bitter or toxic compounds | Pyrrolizidine alkaloids, glucosinolates |

| Signaling | Act as chemical messengers between cells | Flavonoids, strigolactones |

| Pollination | Attract pollinators through chromo-pigments | Carotenoids, anthocyanins |

| Symbiosis | Facilitate ecological associations | Nod factors in rhizobia-legume symbiosis |

| Environmental Adaptation | Protect against biotic and abiotic stresses | Osmoprotectants, phytoalexins |

Current Research Methodologies

Advanced Screening and Analytical Techniques

The field of natural product drug discovery is experiencing a paradigm shift due to advanced technologies that increase speed, accuracy, and sustainability [2]. Traditional discovery workflows are being enhanced by high-throughput screening, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and omics technologies, which collectively streamline compound identification and development [2].

Advanced analytical techniques including ultrasonic-assisted extraction, supercritical fluid extraction, and various chromatographic methods have revolutionized the isolation and purification of natural bioactive compounds [5]. Characterization techniques such as mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and high-performance liquid chromatography provide detailed insights into chemical composition and structural elucidation [5].

Natural Product Drug Discovery Workflow. The diagram outlines the standard pipeline for discovering bioactive natural products, from initial extraction to final compound optimization. Key steps include bioassay-guided fractionation and target identification to ensure therapeutic relevance. UAE: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction; SFE: Supercritical Fluid Extraction; MS: Mass Spectrometry; NMR: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance; HPLC: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography.

Genomics and Bioinformatics Approaches

The integration of genome mining and biosynthetic engineering has revolutionized natural product discovery, offering solutions to longstanding challenges in the field [2]. Advances in understanding NP biosynthetic pathways, coupled with sophisticated genomic analysis tools, have paved the way for systematic exploration of microbial genomes [2].

Tools such as CRISPR-Cas systems, artificial intelligence, and bioinformatics platforms are accelerating hit discovery, de-replication, and biosynthetic pathway engineering, overcoming long-standing barriers to NP research [2]. Genome mining tools like DeepBGC and AntiSMASH enable rapid prediction and characterization of biosynthetic gene clusters, facilitating the discovery of novel compounds [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bioactivity-Guided Fractionation of Plant Extracts

Principle: This protocol outlines a standardized approach for the extraction, fractionation, and identification of bioactive compounds from plant material using bioactivity-guided fractionation to isolate natural products with therapeutic potential [7] [5].

Materials:

- Plant material (dried and powdered)

- Extraction solvents (methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate, hexane)

- Chromatography media (silica gel, Sephadex LH-20, C18 reverse-phase resin)

- Cell lines for bioassays (e.g., cancer cells, microbial strains)

- Analytical instruments (HPLC, MS, NMR)

Procedure:

- Extraction: Macerate 500g of dried plant material in 2L of methanol for 24 hours at room temperature with occasional stirring. Filter through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and concentrate under reduced pressure at 40°C to obtain crude extract.

- Bioactivity Screening: Test crude extract for desired biological activity (e.g., cytotoxicity, antimicrobial activity) using appropriate assays. Proceed with fractionation only if significant activity (IC50 < 100 μg/mL) is observed.

- Solvent Partitioning: Suspend crude extract in 90% aqueous methanol and partition successively with hexane, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol (3 × 200 mL each). Concentrate each fraction under reduced pressure.

- Bioassay-Guided Fractionation: Test all fractions for bioactivity and select the most active for further separation. For the active ethyl acetate fraction (2g):

- Subject to vacuum liquid chromatography on silica gel (200-400 mesh) with step gradient elution from hexane to methanol.

- Combine similar fractions based on TLC profiling to yield 8-10 primary fractions.

- Test each primary fraction for bioactivity.

- Further Purification: For active primary fractions:

- Purify by Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography using methanol as eluent.

- Further separate by semi-preparative HPLC (C18 column, gradient elution with acetonitrile-water).

- Monitor purity by analytical HPLC and confirm structure by NMR and MS.

Troubleshooting:

- If fractionation yields inactive compounds, consider synergistic effects and test combinations of fractions.

- For complex mixtures, employ hyphen techniques like LC-MS-NMR for dereplication [4].

Protocol 2: Genome Mining for Natural Product Discovery

Principle: This protocol utilizes bioinformatics tools to identify biosynthetic gene clusters in microbial genomes, followed by heterologous expression to discover novel natural products [4] [2].

Materials:

- Bacterial/fungal strains or environmental DNA samples

- Bioinformatics software (AntiSMASH, DeepBGC)

- PCR reagents and cloning vectors

- Heterologous expression host (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor)

- Fermentation equipment

Procedure:

- Genome Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequence genome of target organism using Illumina or PacBio platforms.

- Annotate genome using RAST or Prokka.

- Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Identification:

- Submit annotated genome to AntiSMASH for identification of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs).

- Analyze results for novel or silent BGCs with potential novel chemistry.

- Cluster Activation:

- Design primers to amplify entire BGC or key regulatory genes.

- Clone BGC into appropriate expression vector (e.g., BAC, cosmic).

- Introduce construct into heterologous host for expression.

- Metabolite Analysis:

- Culture recombinant strains under various conditions (media, temperature, aeration).

- Extract metabolites with organic solvents and analyze by LC-HRMS.

- Compare metabolic profiles with wild-type strains to identify novel compounds.

- Structure Elucidation:

- Ispute novel compounds using preparative HPLC.

- Determine structures using NMR (1D and 2D) and high-resolution MS.

- Test compounds for biological activity in relevant assays.

Troubleshooting:

- For silent clusters, consider promoter engineering or co-cultivation to activate expression.

- If heterologous expression fails, optimize codon usage or refactor cluster design [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| AntiSMASH | Identifies biosynthetic gene clusters in genomic data | Genome mining for novel natural products [2] |

| GNPS (Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking) | Facilitates mass spectrometry data sharing and annotation | Dereplication and compound identification [4] |

| Sephadex LH-20 | Size exclusion chromatography medium for natural product separation | Fractionation of crude extracts by molecular size [5] |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Genome editing for pathway engineering | Activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters [2] |

| HPLC-MS Systems | High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry | Compound separation, quantification, and identification [5] |

| Dihydroevocarpine | Dihydroevocarpine, CAS:15266-35-0, MF:C23H35NO, MW:341.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Nisamycin | Nisamycin, CAS:150829-93-9, MF:C24H27NO6, MW:425.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

- Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs): Used in phenotypic screening platforms for evaluating natural product bioactivity and toxicity in human-relevant systems [2].

- C18 Reverse-Phase Resin: Essential for final purification steps of medium to non-polar natural products through preparative HPLC [5].

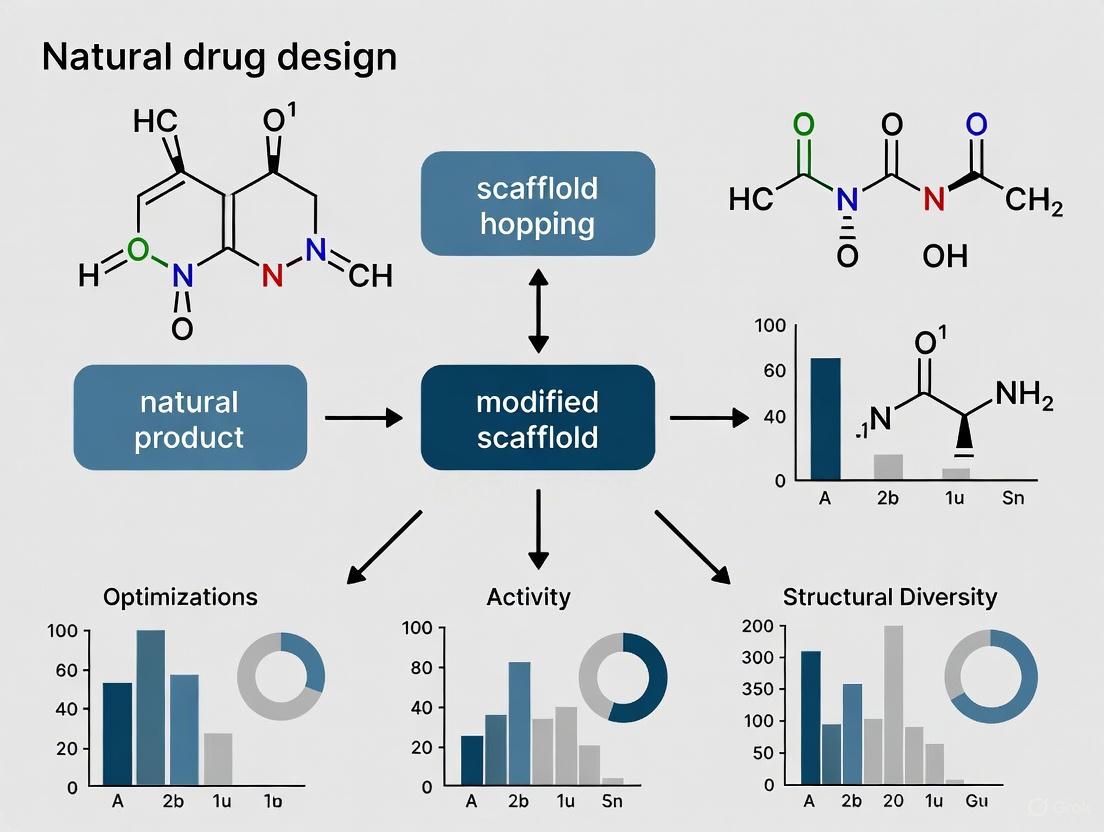

Application in Scaffold Hopping Research

Natural products serve as excellent starting points for scaffold hopping approaches in drug discovery [8]. Scaffold hopping involves modifications to the core structure of an existing bioactive molecule to create new patentable molecules with potentially improved properties [8].

The complex molecular architectures of natural products, honed by evolutionary selection for bioactivity, provide privileged scaffolds that can be optimized through various hopping strategies [8]. These include heterocycle replacement, ring opening or closure, and peptidomimetics to enhance drug-like properties while maintaining biological activity [8].

Scaffold Hopping Strategy for Natural Products. This diagram illustrates how natural product scaffolds can be modified through various hopping approaches to generate diverse analog libraries for lead optimization. Multiple structural modification strategies are employed to enhance drug-like properties while maintaining core bioactivity.

Table 4: Successful Natural Product-Derived Drugs Developed Through Scaffold Hopping

| Original Natural Product | Scaffold Hopping Approach | Resulting Drug/Candidate | Therapeutic Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roxadustat | Heterocycle replacement | Novel HIF-PHD inhibitors | Renal anemia treatment [8] |

| GLPG1837 | Ring closure and expansion | SBD-100 | Cystic fibrosis (enhanced potency) [8] |

| Imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazine TTK inhibitors | Iterative heterocycle replacement | CFI-402257 | Anticancer agent (improved exposure) [8] |

| Sorafenib | Ring opening and amide bond modification | Quinazoline-2-carboxamide analogs | Enhanced VEGFR2 inhibition [8] |

Natural products remain a cornerstone of pharmaceutical innovation due to their unparalleled structural diversity, evolutionary optimization, and proven therapeutic potential [3] [2]. Their historical success in treating various diseases, combined with inherent bioactivity honed through millions of years of evolution, positions them as invaluable resources for addressing current and future health challenges [6] [4].

The integration of modern technologies—including genomics, artificial intelligence, and advanced analytical techniques—with traditional knowledge is revitalizing natural product research [4] [2]. These developments are overcoming historical limitations and creating new opportunities to harness nature's chemical ingenuity for drug discovery, particularly through strategies such as scaffold hopping that optimize natural scaffolds for clinical application [8]. As global health challenges continue to evolve, natural products will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of therapeutic development.

Scaffold hopping is a fundamental strategy in modern medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. It is defined as the process of modifying the central molecular core, or scaffold, of a known bioactive compound to generate a novel chemotype while preserving or improving its biological activity [9] [10]. The core objective is to identify isofunctional molecular structures with significantly different molecular backbones [11].

This approach is pivotal for overcoming limitations associated with existing lead compounds, such as poor pharmacokinetics, toxicity, or intellectual property restrictions [12] [10]. By generating structurally novel compounds that retain the desired biological function, scaffold hopping enables researchers to create "me-better" or "fast-follower" drugs, expand the intellectual property space, and explore uncharted regions of chemical space for bioactive molecules [12] [13]. Its application is particularly valuable in natural product-based drug design, where complex structures often require optimization for drug-like properties [12] [14].

A Classification System for Scaffold Hops

The structural changes in scaffold hopping can be systematically categorized based on the degree and nature of the modification to the parent molecule. The following table outlines a widely used classification system.

Table 1: A Classification Framework for Scaffold Hopping

| Degree of Hop | Core Modification | Key Characteristics | Exemplar Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1° (Heterocyclic Replacement) | Replacement, addition, or swap of heteroatoms within a ring system [9] [10]. | Retains the core spatial pharmacophore arrangement; tunes physicochemical properties [10]. | Sildenafil to Vardenafil: Swap of carbon and nitrogen atoms in a fused ring system [9] [10]. |

| 2° (Ring Opening or Closure) | Breaking a ring to create an acyclic chain or forming a new ring to rigidify a structure [9]. | Can significantly alter molecular flexibility and entropic penalties for binding [9]. | Morphine to Tramadol: Ring opening of a rigid, fused system to a more flexible molecule [9]. |

| 3° (Peptidomimetics) | Replacement of a peptide backbone with non-peptide moieties [9]. | Mimics the topology of a peptide while improving metabolic stability and oral bioavailability [9]. | Conversion of a therapeutic peptide (AMP1) to a small, non-peptide synthetic mimetic [12]. |

| 4° (Topology-Based Hopping) | Identification of cores with similar shape and pharmacophore features but distinct atomic connectivity [9]. | Leads to the highest degree of structural novelty; often relies on 3D shape and electrostatic similarity [9] [11]. | Use of the FTrees method to find distant chemical relatives based on "fuzzy pharmacophores" [11]. |

Computational Protocols for Scaffold Hopping

Several computational methodologies have been developed to facilitate scaffold hopping. The protocols below detail two primary approaches: one leveraging deep learning and another based on virtual screening with pharmacophore constraints.

â—ˆ Protocol 1: Deep Learning-Based Scaffold Hopping with DeepHop

DeepHop formulates scaffold hopping as a supervised molecule-to-molecule translation task, conditioned on a specific protein target [13].

- Objective: To generate a "hopped" molecule (Y) from a reference molecule (X) for a target (Z), such that Y has improved bioactivity, high 3D similarity, but low 2D similarity to X [13].

- Data Preparation and Model Training:

- Data Curation: From a bioactivity database (e.g., ChEMBL), curate pairs of molecules ((X; Y)\|Z) where, for a given target Z, molecule Y has significantly improved bioactivity (e.g., pChEMBL value ≥ 1) over X, with a 2D scaffold Tanimoto similarity ≤ 0.6 and a 3D shape similarity ≥ 0.6 [13].

- Model Architecture: Employ a multimodal Transformer neural network. The model integrates:

- Molecular 2D graph information.

- Molecular 3D conformer information processed by a spatial graph neural network.

- Protein sequence information processed by a Transformer encoder [13].

- Training: Train the model to translate the reference molecule X to the improved molecule Y using the constructed paired dataset [13].

- Application and Fine-Tuning:

- Input: A reference molecule (X) and its target protein (Z).

- Generation: The trained DeepHop model generates novel candidate molecules (Y).

- Validation: A deep QSAR model (e.g., Multi-Task Deep Neural Network) is used for rapid virtual profiling of the generated molecules to predict bioactivity [13].

- Generalization: The model can be fine-tuned on a small set of active compounds for a new target protein not included in the original training [13].

The workflow for this deep learning approach is standardized as follows:

â—ˆ Protocol 2: Virtual Screening with Pharmacophore Constraints

This protocol uses structure-based virtual screening, enhanced with pharmacophore constraints, to identify scaffold hops from commercial or internal compound libraries [11].

- Objective: To identify novel chemical entities that bind to the same target as a known ligand, utilizing a defined protein binding pocket.

- Methodology:

- Target Structure Preparation:

- Obtain a 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or the PDB).

- Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and optimizing side-chain conformations.

- Pharmacophore Definition:

- Based on the binding mode of a known ligand or analysis of the binding site, define key pharmacophore features. These may include: Hydrogen Bond Donor, Hydrogen Bond Acceptor, Positive Ionizable, Hydrophobic Region, Aromatic Ring [11].

- Virtual Screening Workflow:

- Docking: Perform molecular docking of a compound library (e.g., ZINC, PubChem) into the target's binding site using software like SeeSAR [11].

- Pharmacophore Constraint: Apply the predefined pharmacophore features as a filter. Only consider docking poses that match these critical interactions for further analysis [11].

- Scoring and Ranking: Rank the filtered compounds based on their predicted binding affinity (docking score) and the quality of the pharmacophore fit.

- Post-Screening Analysis:

- Visually inspect the top-ranked compounds to verify the binding mode and interactions.

- Analyze the scaffold of the hits to confirm novelty compared to the original lead.

- Target Structure Preparation:

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process within the virtual screening workflow:

Experimental Validation of Scaffold Hops

Computational predictions require rigorous experimental validation to confirm successful scaffold hopping. The following table outlines key biophysical and cellular assays used for this purpose.

Table 2: Key Assays for Experimental Validation of Scaffold Hops

| Assay Type | Measured Parameter | Protocol Summary | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intact Mass Spectrometry | Direct detection of ligand-bound protein complex and binding stoichiometry [15]. | Protein-ligand complexes are buffer-exchanged into volatile ammonium acetate and analyzed by native mass spectrometry [15]. | Confirms stabilization of a protein-protein interaction (PPI) by a molecular glue, demonstrating cooperative binding [15]. |

| Time-Resolved FRET (TR-FRET) | Change in fluorescence resonance energy transfer between labeled binding partners [15]. | A fluorescent donor and acceptor are attached to the two interacting proteins. Ligand-induced proximity increases FRET efficiency, measured over time [15]. | Quantifies the potency (EC50) of a scaffold hop in stabilizing or inhibiting a PPI in a purified system [15]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Binding kinetics (association rate kon, dissociation rate koff) and affinity (K_D) [15]. | One binding partner is immobilized on a sensor chip. Analyte containing the other partner flows over it, and binding-induced refractive index changes are monitored in real-time [15]. | Determines if the scaffold hop maintains or improves binding affinity and residence time compared to the original ligand. |

| NanoBRET | Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer in live cells [15]. | Proteins of interest are tagged with NanoLuc luciferase (donor) and HaloTag (acceptor). Ligand-induced interaction is measured via BRET signal in live cells [15]. | Validates target engagement and functional efficacy (e.g., PPI stabilization) of scaffold hops in a physiologically relevant, cellular context [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful execution of scaffold hopping campaigns relies on a suite of computational tools and chemical resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Scaffold Hopping

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Scaffold Hopping |

|---|---|---|

| Cresset Blaze / Spark [12] | Software | Blaze: Virtual screening of vendor libraries for whole-molecule replacement. Spark: Fragment replacement to generate ideas for synthesis [12]. |

| AnchorQuery [15] | Software / Virtual Library | Pharmacophore-based screening of a >31 million compound library of readily synthesizable (via MCR chemistry) scaffolds [15]. |

| SeeSAR & ReCore [11] | Software | SeeSAR: Interactive structure-based design and docking. ReCore: Topological replacement of molecular fragments based on 3D vector geometry [11]. |

| FTrees / infiniSee [11] | Software | FTrees: Similarity searching based on "Feature Trees" (fuzzy pharmacophores) to find distant chemical relatives in large chemical spaces [11]. |

| Scaffold Hunter [16] | Software | A visual analytics framework for analyzing chemical compound data, featuring scaffold tree visualization, clustering, and dataset comparison [16]. |

| ChEMBL Database [13] [17] | Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for training models and extracting bioactivity data [13] [17]. |

| ZINC Database [11] | Database | A freely available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening [11]. |

| Groebke-Blackburn-Bienaymé (GBB) Reaction [15] | Chemical Reaction | A multi-component reaction used to rapidly synthesize drug-like imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine scaffolds identified through computational design [15]. |

| Trovafloxacin mesylate | Trovafloxacin mesylate, MF:C21H19F3N4O6S, MW:512.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lethedoside A | Lethedoside A | Lethedoside A is a natural flavone for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human or veterinary use. |

In the pursuit of novel therapeutics, the strategy of scaffold hopping has become a cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry, particularly within natural product-based drug design. This approach, defined as the modification of a compound's central core structure to generate a novel chemotype while retaining or improving biological activity, serves as a powerful method to overcome limitations of original leads [18] [9]. The ultimate goal is to discover structurally novel compounds that maintain efficacy against a biological target while achieving superior pharmacological properties [9].

The conceptual foundation of scaffold hopping, introduced in 1999, emphasizes two key components: different core structures and similar biological activities relative to the parent compound [18] [9]. This strategy appears to challenge the traditional similarity-property principle but is instead enabled by a more sophisticated understanding of molecular recognition. Ligands that fit the same protein pocket often share essential three-dimensional features—such as shape and electrostatio potential surface—even if their underlying two-dimensional architectures belong to different chemotypes [18].

This application note systematically classifies scaffold hopping approaches, provides detailed experimental protocols, and frames these methodologies within the context of advancing natural product-based drug discovery.

Established Classification of Scaffold Hopping Approaches

Scaffold hopping strategies are broadly categorized into four distinct classes based on the degree and nature of structural modification applied to the parent molecule [18] [19] [9]. These classes represent a spectrum of structural change, from minor atomic substitutions to complete topological reorganization.

Table 1: Fundamental Classification of Scaffold Hopping Approaches

| Hop Class | Degree of Structural Novelty | Core Methodology | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1° Hop: Heterocycle Replacement | Low | Swapping or replacing atoms (e.g., C, N, O, S) within a ring system. | Lead optimization, patent circumvention, improving physicochemical properties like solubility [18] [9]. |

| 2° Hop: Ring Opening or Closure | Low to Medium | Breaking bonds to open fused rings or forming new bonds to create ring systems and control molecular flexibility [18] [9]. | Modifying pharmacokinetic profiles, enhancing potency by reducing entropy loss upon binding [18]. |

| 3° Hop: Peptidomimetics | Medium | Replacing peptide backbones with non-peptide moieties to mimic the spatial arrangement of key pharmacophoric groups [18] [9]. | Developing drug-like molecules from bioactive but metabolically unstable peptides [18]. |

| 4° Hop: Topology-Based Hopping | High | Identifying or designing cores with different connectivity but similar shape and pharmacophore alignment in 3D space [18] [19] [9]. | Discovering truly novel chemotypes, high-risk lead hopping for challenging targets [18]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and decision-making pathways connecting these four classes of scaffold hops:

Experimental Protocols & Case Studies

Protocol 1: Topology-Based Scaffold Hopping for Molecular Glues

Molecular glues, which stabilize protein-protein interactions (PPIs), represent a challenging and promising frontier. A 2025 study detailed a scaffold-hopping approach to develop molecular glues for the 14-3-3σ/ERα complex, starting from a known covalent molecular glue [20].

Objective: To design a novel, non-covalent molecular glue scaffold with improved drug-like properties using a computational topology-based hopping approach followed by synthesis via multicomponent reactions (MCRs) [20].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents & Solutions for Molecular Glue Development

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| AnchorQuery Software | Pharmacophore-based screening tool for a 31M+ compound library synthesizable via one-step MCRs [20]. | Virtual screening to identify novel scaffolds based on anchor and pharmacophore points from a known ligand. |

| GBB-3CR Reaction Components | Groebke-Blackburn-Bienaymé multicomponent reaction using aldehydes, 2-aminopyridines, and isocyanides [20]. | Rapid synthesis of the proposed imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine scaffold, enabling generation of diverse analogs. |

| TR-FRET Assay Kit | Time-Resolved Förster Resonance Energy Transfer assay for measuring PPI stabilization in a biochemical setting. | Biophysical validation of molecular glue efficacy in stabilizing the 14-3-3σ/ERα interaction. |

| NanoBRET Assay System | Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer assay configured for live-cell PPI analysis. | Cellular confirmation of target engagement and PPI stabilization under physiological conditions. |

Methodology:

- Template Definition: Use a high-resolution crystal structure of the lead compound (e.g., compound 127, PDB: 8ALW) bound to the target PPI interface [20].

- Anchor Identification: Define a deeply buried, critical structural motif (e.g., a p-chloro-phenyl ring) as the "anchor." This anchor is kept constant during the virtual screen [20].

- Pharmacophore Query: From the original ligand's binding pose, define a set of three additional key pharmacophore points (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions). This 3-point pharmacophore, combined with the anchor, is used to query the MCR virtual library in AnchorQuery [20].

- Hit Selection & Synthesis: Rank proposed scaffolds by RMSD fit to the original pharmacophore. Synthesize top-ranking scaffolds, prioritizing those like the imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines accessible via the GBB-3CR, allowing for rapid derivatization [20].

- Biophysical & Cellular Validation: Profile synthesized analogs using orthogonal assays:

- Intact Mass Spectrometry: Confirm binding and stoichiometry.

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Quantify binding affinity and kinetics.

- TR-FRET: Measure PPI stabilization in a biochemical context.

- NanoBRET: Confirm functional PPI stabilization in live cells [20].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: Enzyme-Enabled Scaffold Hopping in Terpenoid Synthesis

A groundbreaking 2024 study demonstrated a hybrid enzymatic-chemical strategy for scaffold hopping in complex natural product synthesis, moving beyond purely computational designs [14].

Objective: To efficiently generate diverse terpenoid natural product scaffolds from a single, commercially available terpenoid precursor via enzymatic oxidation followed by selective chemical rearrangement [14].

Methodology:

- Selection of Platform Scaffold: Choose a synthetically accessible and versatile natural product scaffold as the starting point (e.g., sclareolide, a commercially available sesquiterpene lactone) [14].

- Enzymatic Functionalization: Employ engineered cytochrome P450 enzymes to perform site-selective oxidation (e.g., at the C3 position of sclareolide) that is challenging to achieve with traditional synthetic chemistry. This creates a key oxygenated intermediate [14].

- Scaffold Diversification: Use the introduced oxygen functionality as a chemical handle to direct subsequent rearrangement reactions (e.g., Wagner-Meerwein shifts, cyclizations). By varying the reaction conditions, this single intermediate can be diverted down multiple synthetic pathways [14].

- Target Synthesis: Apply this strategy to synthesize distinct terpenoid natural products with unique carbon frameworks from the common intermediate. The study successfully synthesized merosterolic acid B, cochlioquinone B, (+)-daucene, and dolasta-1(15),8-diene from oxidized sclareolide [14].

This protocol challenges traditional retrosynthetic analysis by establishing a shared, enzyme-generated intermediate for multiple target scaffolds, significantly improving synthetic efficiency.

The Evolving Toolbox: AI-Driven Molecular Representation

Modern scaffold hopping is increasingly powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and advanced molecular representation methods, which move beyond traditional fingerprint-based approaches [19].

- Language Model-Based Representations: Models like transformers treat molecular strings (e.g., SMILES) as a chemical language, learning contextual relationships between atoms and functional groups to generate novel, valid structures [19].

- Graph-Based Representations: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) natively represent molecules as graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges), enabling them to learn from both local atomic environments and global topological structure, which is crucial for recognizing scaffold-level similarities [19] [21].

- 3D Interaction-Driven Models: For target-informed hopping, models like DeepFrag and FRAME leverage 3D structural data of protein-ligand complexes. DeepFrag frames the problem as a classification task, predicting optimal fragments to fill a binding pocket, while FRAME uses equivariant neural networks to explicitly model protein-ligand interactions and select optimal connection points [21].

These AI-driven strategies can be categorized based on their approach to structural modification, as shown in the table below.

Table 3: AI-Driven Models for Molecular Modification in Scaffold Hopping

| Model Name | Core Architecture | Modification Strategy | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepFrag [21] | 3D Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) | Fragment Splicing | Treats fragment replacement as a classification task based on the protein-ligand complex structure. |

| FREED/FREED++ [21] | Graph CNN + Reinforcement Learning (RL) | Fragment Splicing | Uses RL to efficiently explore chemical space and generate molecules with high docking scores. |

| FRAME [21] | SE(3)-Equivariant Neural Network | Fragment Splicing | Explicitly models 3D protein-ligand interactions (H-bonds, π-π) for dynamic fragment selection. |

| MolEdit3D [21] | 3D Graph Neural Network | Fragment Editing & Splicing | A 3D graph editing model allowing for precise atomic and fragment-level modifications. |

| TACOGFN [21] | GFlowNet + Graph Transformer | Fragment Splicing | Incorporates target pocket information into a generative flow network for guided fragment addition. |

The systematic classification of scaffold hops into heterocycle replacements, ring operations, peptidomimetics, and topology-based changes provides a robust conceptual framework for medicinal chemists. This is particularly valuable in natural product research, where the goal is often to translate complex, bioactive scaffolds into viable drug leads. The integration of computational protocols—ranging from pharmacophore-based MCR screening to FEP-guided design—with innovative experimental strategies, such as enzyme-enabled diversification, is redefining the scaffold hopping landscape. As AI-driven molecular representation and generation models continue to mature, they promise to further accelerate the discovery of novel chemotypes, enhancing our ability to explore chemical space and address unmet medical needs through natural product-inspired design.

Application Notes

The strategic modification of natural product (NP) scaffolds is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling the optimization of bioactive compounds for enhanced efficacy and druggability. This approach leverages the inherent, evolutionarily refined biological activities of NPs while overcoming limitations such as poor bioavailability, low potency, or high toxicity. The following application notes detail a transformative protocol for the diversification of terpenoid scaffolds, a class of NPs renowned for their structural complexity and broad bioactivity.

A pioneering application of enzyme-enabled scaffold hopping is demonstrated in the work of Renata and colleagues, who developed a versatile chemoenzymatic strategy to generate diverse terpenoid frameworks from a common precursor [14]. This method challenges the conventional retrosynthetic paradigm of designing a custom synthesis for each distinct molecular target. Instead of viewing an enzymatic modification as a final step, the team treated a biocatalytically installed functional group as a handle for subsequent abiotic skeletal rearrangements [22] [23].

Core Application Workflow: The process begins with sclareolide, a commercially available sesquiterpene lactone with a drimane-type skeleton [14]. The key enabling step involves the highly selective oxidation of a single carbon atom (C-3) on this scaffold using engineered cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP450s) [14]. This biocatalytic transformation, difficult to achieve with traditional chemical methods, produces an alcohol intermediate. This intermediate is not an end-product but a versatile platform for "scaffold hopping" – a process that intentionally alters the core connectivity of the molecule [23]. Through carefully designed chemical reactions (e.g., ring-opening, rearrangement, and cyclization sequences), this single oxidized intermediate can be diverted down multiple synthetic pathways to produce terpenoids with vastly different carbon skeletons [14] [22].

Outcomes and Significance: Using this strategy, the research team successfully synthesized four distinct terpenoid natural products from sclareolide: merosterolic acid B, cochlioquinone B, (+)-daucene, and dolasta-1(15),8-diene [14] [22]. This demonstrates the remarkable structural divergence achievable from a single starting point. The implications for drug discovery are profound, as this platform technology significantly enhances synthetic efficiency. It saves time and cost by providing a shared entry point with branching pathways, thereby accelerating the exploration of structure-activity relationships (SAR) around complex terpenoid scaffolds for medicinal chemistry programs [14].

Table 1: Terpenoid Natural Products Synthesized via Enzyme-Enabled Scaffold Hopping

| Natural Product | Class | Key Structural Features Achieved | Potential/Reported Bioactivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Merosterolic Acid B | Meroterpenoid | Complex ring system integrated with non-terpenoid structural units | Not specified in search results |

| Cochlioquinone B | Sesquiterpene-quinone | Fused quinonoid moiety installed via oxidation and rearrangement [23] | Environmentally relevant terpenoid [23] |

| (+)-Daucene | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon | Altered ring junctions from the original drimane core [23] | Serves as a critical biosynthetic intermediate [23] |

| Dolasta-1(15),8-diene | Diterpene hydrocarbon | Unique double bond placements and ring fusion patterns [23] | Not specified in search results |

Protocols

Protocol 1: Enzyme-Enabled Scaffold Hopping for Terpenoid Diversification

This protocol outlines the detailed methodology for the oxidative diversification of sclareolide and subsequent abiotic rearrangements to access distinct terpenoid skeletons, as pioneered by Renata's group [14] [22] [23].

I. Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Sclareolide | The starting material; a commercially available sesquiterpene lactone providing a defined drimane-type scaffold. |

| Engineered Cytochrome P450 Enzymes (CYP450) | Biocatalysts engineered for high regio- and stereoselective oxidation of inert C-H bonds, installing a handle (alcohol) for further functionalization. |

| Cofactor System (e.g., NADPH) | Required for the enzymatic activity of CYP450s to drive the oxidation reaction. |

| Appropriate Buffer | To maintain optimal pH and ionic strength for enzymatic stability and activity. |

| Abiotic Reagents | Chemical reagents (e.g., acids, bases, catalysts) for skeletal rearrangements post-oxidation, enabling scaffold hopping. |

Essential Equipment: Bioreactor or controlled environment shaker for enzymatic reactions, standard organic synthesis glassware, analytical instruments (HPLC, LC-MS, NMR) for reaction monitoring and purification.

II. Experimental Procedure

Step 1: Enzymatic C-H Hydroxylation of Sclareolide

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a reaction mixture containing sclareolide (e.g., 1.0 mmol) in a suitable aqueous-organic buffer system. Add the engineered CYP450 enzyme and a cofactor regeneration system (e.g., NADP+, glucose-6-phosphate, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) to sustain the catalytic cycle.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture with gentle agitation at a temperature and pH optimized for the specific engineered enzyme (e.g., 30°C, pH 7.4) for a predetermined time (e.g., 12-24 hours) to achieve high conversion.

- Monitoring and Work-up: Monitor the reaction progress by LC-MS or TLC. Upon completion, extract the product using an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate). Purify the crude extract via flash chromatography to isolate the C-3 hydroxylated sclareolide intermediate. Confirm the structure and regiochemistry by ( ^1 \text{H} ) and ( ^13\text{C} ) NMR spectroscopy [14].

Step 2: Abiotic Skeletal Rearrangement (Scaffold Hopping) This step is target-dependent. The following are generalized pathways based on the synthesized products.

- Pathway to Merosterolic Acid B/Cochlioquinone B:

- Subject the alcohol intermediate to an oxidative ring-opening reaction.

- Employ tailored conditions (e.g., specific oxidizing agents, controlled temperatures) to guide the formation of a new reactive species.

- Initiate cyclization and rearrangement sequences to form the distinct carbon frameworks characteristic of merosterolic acid and cochlioquinone B, the latter involving installation of a quinone moiety [23].

- Pathway to (+)-Daucene/Dolasta-diene:

- Activate the alcohol group (e.g., via mesylation or tosylation) to form a better leaving group.

- Treat the activated intermediate with a strong base or Lewis acid to promote a concerted ring contraction/expansion or Wagner-Meerwein-type rearrangement.

- Carefully control reaction parameters (e.g., solvent, temperature, concentration) to steer the rearrangement towards the desired hydrocarbon scaffold of (+)-daucene or dolasta-diene [23].

Step 3: Purification and Characterization

- Purify each final terpenoid product using techniques such as preparative thin-layer chromatography (PTLC) or HPLC.

- Characterize each compound fully using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and 1D/2D NMR spectroscopy. Compare the spectral data with literature values to confirm identity and purity [14] [22].

III. Data Analysis and Interpretation

The success of the protocol is determined by the structural confirmation of all final products. The key data for comparison is summarized below.

Table 2: Quantitative Data for Synthesized Terpenoids from Sclareolide

| Natural Product | Number of Synthetic Steps from Sclareolide (Representative) | Overall Yield (Representative, Over Multiple Steps) | Key Analytical Data (e.g., Specific Rotation [α]D) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Merosterolic Acid B | Not specified in search results | Not specified in search results | Not specified in search results |

| Cochlioquinone B | Not specified in search results | Not specified in search results | Not specified in search results |

| (+)-Daucene | Not specified in search results | Not specified in search results | The "(+)" designation indicates the compound is dextrorotatory. |

| Dolasta-1(15),8-diene | Not specified in search results | Not specified in search results | Not specified in search results |

Note: The source articles announce the achievement of the synthesis but do not report detailed quantitative yield data or step counts. The primary analytical confirmation is based on NMR and MS comparison with authentic samples or literature data [14] [22].

IV. Visual Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the enzyme-enabled scaffold hopping strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Enzyme-Enabled Terpenoid Diversification

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Cytochrome P450s | Biocatalyst | Key to regioselective C-H activation; provides the critical "handle" for downstream diversification that is unattainable purely chemically [14]. |

| Sclareolide | Natural Product Scaffold | Commercially available, complex starting material that serves as a versatile and privileged platform for generating structural diversity [14] [23]. |

| Cofactor Regeneration System | Biochemical Reagent | Maintains the activity of oxidative enzymes like CYP450s over prolonged reactions, improving efficiency and atom economy. |

| Molecular Generative AI Models | Computational Tool | For target-unknown scenarios, these AIDD models can propose novel structural modifications and predict bioactivity, guiding scaffold hopping efforts [21]. |

| Fragment Hotspot Maps (FHMs) | Computational Tool | Used in silico to identify optimal sites on a protein target for fragment binding, informing the design of new scaffolds for specific targets [21]. |

| Aprindine | Aprindine, CAS:33237-74-0, MF:C22H30N2, MW:322.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dodecamethylpentasiloxane | Dodecamethylpentasiloxane, CAS:141-63-9, MF:C12H36O4Si5, MW:384.84 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodologies for Scaffold Hopping: From Traditional Rules to AI-Driven Generation

In the field of natural product-based drug design, scaffold hopping—the identification of isofunctional molecular structures with significantly different molecular backbones—is a central strategy for discovering novel lead compounds with improved properties and intellectual potential [9]. This process enables researchers to transition from complex natural product scaffolds to synthetically accessible mimetics while preserving biological activity [24]. Traditional computational methods for scaffold hopping primarily rely on 2D molecular fingerprints and 3D pharmacophore models, each offering distinct advantages for exploring the complex chemical space of natural products [25] [26]. This application note details standardized protocols for employing these methods within natural product research programs, complete with performance benchmarks and implementation workflows.

Molecular Fingerprints for Natural Product Analysis

Molecular fingerprints are vector representations that encode molecular structures into binary, count, or categorical formats based on specific structural or chemical patterns. They are predominantly used for rapid similarity searching and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling [26].

Key Fingerprint Types and Their Performance on Natural Products

Natural products often possess distinct chemical characteristics compared to synthetic drug-like molecules, including higher molecular complexity, more stereocenters, and a greater fraction of sp³-hybridized carbons [26]. These differences can significantly impact the performance of various fingerprinting algorithms. The table below summarizes the performance of major fingerprint categories on natural product datasets.

Table 1: Performance Evaluation of Molecular Fingerprints on Natural Product Datasets

| Fingerprint Category | Representative Examples | Basis of Calculation | Performance on Natural Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular Fingerprints | ECFP, FCFP [26] | Atom-centered radial substructures | Good performance, but can be outperformed by other fingerprints for specific NP bioactivity prediction tasks [26]. |

| Path-Based Fingerprints | Atom Pairs (AP), Depth First Search (DFS) [26] | Linear paths through molecular graph | Performance varies; requires benchmarking for specific NP datasets [26]. |

| Pharmacophore Fingerprints | Pharmacophore Pairs (PH2), Triplets (PH3) [26] | Topological distances between pharmacophoric points | Can provide an abstract, interaction-based representation less dependent on specific scaffold [26]. |

| Substructure-Based Fingerprints | MACCS, PubChem [26] | Presence of predefined structural keys | Limited by predefined fragment dictionary, potentially hampering scaffold hopping [27]. |

| String-Based Fingerprints | MHFP, MAP4 [26] | Fragmentation of SMILES strings | MAP4 has shown competitive or superior performance to ECFP in NP bioactivity prediction [26]. |

Experimental Protocol: Fingerprint-Based Virtual Screening for Scaffold Hopping

Principle: This ligand-based protocol uses a known active natural product as a query to identify structurally different compounds with similar bioactivity by calculating molecular similarity in a 2D descriptor space [24].

Materials & Software:

- Query Compound: A known bioactive natural product (e.g., from COCONUT or CMNPD databases) [26].

- Screening Database: A database of candidate compounds (e.g., commercial screening libraries, in-house collections).

- Software: Cheminformatics toolkits (e.g., RDKit, OpenBabel) for fingerprint calculation and similarity searching.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Standardize all molecular structures (query and database compounds). This includes removing salts, neutralizing charges, and generating canonical SMILES [28] [26].

- Fingerprint Selection and Calculation: Based on the benchmarking data in Table 1, select one or more fingerprint types (e.g., MAP4, ECFP, PH2). Calculate fingerprints for both the query natural product and all compounds in the screening database.

- Similarity Calculation: Compute the pairwise similarity between the query fingerprint and every database compound fingerprint. The Tanimoto coefficient (Jaccard similarity) is the most common metric for this purpose [26].

- Ranking and Analysis: Rank the database compounds based on their similarity score to the query. Visually inspect the top-ranking compounds to identify those that maintain core pharmacophoric elements but possess a novel scaffold (Murcko scaffold) [28] [27].

3D Pharmacophore Models for Scaffold Hopping

A pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target" [25] [29]. Pharmacophore modeling abstracts a molecule from its specific chemical structure to a set of generalized features essential for binding, making it inherently powerful for scaffold hopping [25].

Pharmacophore Feature Types and Generation Methods

Table 2: Core Pharmacophore Features and Model Generation Approaches

| Feature Type | Geometric Representation | Interaction Type | Generation Method | Description & Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-Bond Donor (HBD) | Vector or Sphere [25] | Hydrogen Bonding | Structure-Based [25] | Derived from protein-ligand complex crystal structure. Most reliable method. |

| H-Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Vector or Sphere [25] | Hydrogen Bonding | Ligand-Based [25] | Generated from a set of aligned active ligands. Requires known actives. |

| Positive/Negative Ionizable (PI/NI) | Sphere [25] | Ionic | Manual [25] | Built based on deep expert knowledge of target and ligands. |

| Aromatic (AR) | Plane or Sphere [25] | π-Stacking, Cation-π | - | - |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Sphere [25] | Hydrophobic Contact | - | - |

| Exclusion Volumes | Sphere [25] | Steric Clash Prevention | - | Define regions the ligand must not occupy; often from protein structure [25]. |

Experimental Protocol: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation and Screening

Principle: This protocol uses the 3D structure of a biological target (often with a bound natural product ligand) to derive a set of essential interaction features, which are then used as a query to screen for novel scaffolds [25].

Materials & Software:

- Protein Structure: A high-resolution 3D structure of the target (e.g., from PDB), preferably in complex with a ligand.

- Software: Molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL); pharmacophore modeling software (e.g., MOE, LigandScout, Schrödinger's Phase).

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation: Prepare the protein-ligand complex structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and optimizing hydrogen bonds.

- Interaction Analysis: Analyze the binding site to identify key interactions between the ligand (e.g., a natural product) and the protein. Note hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions, and hydrophobic regions.

- Feature Mapping: Map the identified interactions to abstract pharmacophore features (HBA, HBD, H, etc.) and place them in 3D space. Add exclusion volume spheres to represent forbidden regions of the binding site [25].

- Model Validation (Optional but Recommended): Validate the initial model by screening a small dataset of known actives and inactives to ensure it can discriminate between them.

- Virtual Screening: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a query to screen a large, conformationally-enriched database of compounds. The search will identify molecules that can spatially and electronically align with all critical features of the query.

- Post-Processing: The resulting hits, which often possess diverse scaffolds, should be further evaluated by molecular docking and visual inspection [30].

Integrated Workflow and Benchmarking

Combining 2D and 3D Methods

A synergistic approach that leverages the speed of 2D fingerprints and the scaffold-hopping power of 3D pharmacophores is often most effective. A common strategy is to use a 2D similarity pre-filter to narrow down a large database, followed by a more computationally intensive 3D pharmacophore screen on the resulting subset [30]. Furthermore, holistic 3D descriptors like WHALES (Weighted Holistic Atom Localization and Entity Shape) have been developed specifically to bridge the gap between natural products and synthetic mimetics by simultaneously encoding pharmacophore, shape, and partial charge distribution [24] [27].

Performance Benchmarking

The table below provides a comparative overview of the scaffold-hopping performance of different molecular representations, highlighting the effectiveness of 3D methods.

Table 3: Benchmarking the Scaffold-Hopping Performance of Different Molecular Representations

| Molecular Representation | Dimension | Core Principle | Reported Scaffold-Hopping Performance (SDA%)* | Key Advantage for NPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECFPs | 2D | Circular substructures | 73 ± 12 [27] | Fast, widely used, good overall performance [26]. |

| MACCS Keys | 2D | Predefined fragments | 75 ± 12 [27] | Interpretable, but limited by predefined dictionary [27]. |

| CATS2 | 2D | Topological pharmacophore pairs | - | Abstract representation aids hopping [27]. |

| WHIM | 3D | Statistical projection of 3D coordinates | - | Captures overall molecular shape [27]. |

| WHALES | 3D | Holistic integration of shape & pharmacophore | Outperformed benchmarks in 89% of 182 targets [27] | Specifically designed for NP-to-synthetic hopping; high success rate [24] [27]. |

*SDA% (Scaffold Diversity of Actives): The ratio of unique Murcko scaffolds to the number of active compounds retrieved in the top 5% of a virtual screening rank, with higher values indicating better scaffold-hopping ability [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 4: Key Software Tools for Molecular Fingerprint and Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics | Open-source toolkit for cheminformatics | Fingerprint calculation (ECFP, etc.), molecular standardization, and similarity searching [28] [26]. |

| FTrees/InfiniSee | Virtual Screening | Pharmacophore-based similarity search | Algorithm behind the "Scaffold Hopper Mode" to find compounds related by pharmacophore features [30]. |

| ReCore (SeeSAR) | Structure-Based Design | Structure-based core replacement | Suggests molecular motifs that replace a scaffold while maintaining binding interactions and side chains [30]. |

| FlexS | Molecular Alignment | 3D ligand alignment | Used to align candidate compounds to a reference pharmacophore for similarity assessment [30]. |

| MOE | Integrated Suite | Molecular modeling and simulation | Comprehensive environment for pharmacophore model creation (both structure- and ligand-based) and virtual screening [9]. |

| Cetefloxacin | Cetefloxacin|CAS 141725-88-4|RUO | Cetefloxacin is a synthetic fluoroquinolone antibiotic for research use only (RUO). Inhibits DNA gyrase. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Penethamate hydriodide | Penethamate hydriodide, CAS:808-71-9, MF:C22H32IN3O4S, MW:561.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The Weighted Holistic Atom Localization and Entity Shape (WHALES) descriptors represent an advanced molecular representation technique designed to facilitate scaffold hopping in computer-assisted drug discovery. Unlike traditional fingerprints that focus on molecular connectivity or presence of specific fragments, WHALES descriptors simultaneously capture critical information about molecular shape and partial charge distribution in a holistic manner. Originally developed to translate structural and pharmacophore information from bioactive natural products to synthetically accessible isofunctional compounds, WHALES has demonstrated remarkable capability in identifying novel ligand chemotypes that populate uncharted regions of the chemical space while maintaining desired biological activity [31] [32].

The fundamental innovation of WHALES lies in its integration of geometric interatomic distances with atomic physicochemical properties, enabling the identification of structurally diverse compounds that share similar bioactivity profiles. This approach has proven particularly valuable in natural product-based drug design, where complex molecular architectures often serve as inspiration for developing synthetically tractable compounds with improved drug-like properties. By enabling efficient navigation through chemical space, WHALES addresses a key challenge in medicinal chemistry: the discovery of novel bioactive chemotypes through straightforward similarity searching [32].

Theoretical Foundation and Calculation Protocol

Conceptual Framework

WHALES descriptors encode molecular information through a sophisticated algorithm that transforms three-dimensional molecular structures and their electronic properties into a numerical representation. The methodology employs weighted locally-centred atom distances computed for each atom position in a three-dimensional molecular conformation, creating a comprehensive profile that captures molecular shape and charge distribution simultaneously. This holistic approach allows WHALES to identify structurally diverse compounds that share similar steric and electronic properties, making it particularly effective for scaffold hopping applications where traditional fragment-based methods often fail [32].

The theoretical foundation of WHALES rests on the calculation of an atom-centred covariance matrix for each non-hydrogen atom, which captures the distribution of atoms and their partial charges around each atomic center. This matrix incorporates both spatial atomic coordinates and their associated partial charges, creating a weighted representation of the molecular environment that forms the basis for subsequent distance calculations and descriptor generation [32].

Step-by-Step Calculation Protocol

Step 1: Molecular Preparation and Partial Charge Calculation

- Generate a 3D molecular conformation using energy minimization with the MMFF94 force field or similar reliable methods [32]

- Calculate partial atomic charges using either:

Step 2: Atom-Centred Covariance Matrix Computation

For each non-hydrogen atom (j) in the molecule, compute the weighted covariance matrix using the formula:

$${{\bf{S}}}{w(j)}=\frac{{\sum }{i=1}^{n}\,|{\delta }{i}|\cdot ({{\bf{x}}}{i}-{{\bf{x}}}{j}){({{\bf{x}}}{i}-{{\bf{x}}}{j})}^{{\rm{T}}}}{{\sum }{i=1}^{n}\,|{\delta }_{i}|}$$

where:

- (xáµ¢ - xâ±¼) represents the differences between the 3D coordinates of the j-th atomic center and those of any i-th non-hydrogen atom

- |δᵢ| is the absolute value of the partial charge of the i-th atom [32]

Step 3: Atom-Centred Mahalanobis Distance (ACM) Calculation

Compute the ACM distance matrix with the equation:

$${\bf{A}}{\bf{C}}{\bf{M}}\,(i,j)={({{\bf{x}}}{i}-{{\bf{x}}}{j})}^{{\rm{T}}}\cdot {{\bf{S}}}{w(j)}^{-1}\cdot ({{\bf{x}}}{i}-{{\bf{x}}}_{j})$$

This matrix collects all pairwise normalized interatomic distances according to the atom-centred covariance matrix, where atoms located in directions of high variance have smaller distances from the atomic center than those in low-variance regions [32].

Step 4: Atomic Parameter Calculation

From the ACM matrix (excluding diagonal elements), calculate:

- Remoteness degree: Row average of the ACM matrix

- Isolation degree: Column minimum of the ACM matrix

- Ratio values: Isolation degree divided by remoteness value Assign negative values for these parameters for negatively-charged atoms [32].

Step 5: Molecular Descriptor Vector Generation

Calculate the distribution statistics of atomic remoteness, isolation degree, and their ratios to generate 33 WHALES descriptors comprising:

- Minimum and maximum values

- Decile values (10th, 20th, ..., 90th percentiles) This fixed-length descriptor vector enables molecular similarity comparisons independent of molecular size [32].

Table 1: WHALES Descriptor Variants Based on Partial Charge Calculation Methods

| Descriptor Version | Partial Charge Method | Complexity Level | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHALES-DFTB+ | DFTB+ accelerated quantum mechanical simulation | High chemical detail | High-precision scaffold hopping |

| WHALES-GM | Gasteiger-Marsili connectivity-based method | Medium chemical detail | Large-scale virtual screening |

| WHALES-shape | δᵢ = 1 for all atoms (no charge information) | Basic shape-based representation | Shape-focused similarity searching |

Workflow Visualization

Application Notes: WHALES for Scaffold Hopping

Retrospective Virtual Screening Benchmark

WHALES descriptors have been rigorously evaluated for their scaffold-hopping potential through comprehensive benchmarking studies. In a systematic analysis comparing WHALES with seven state-of-the-art molecular representations across 30,000 bioactive compounds and 182 biological targets, WHALES demonstrated superior performance in identifying structurally diverse active compounds [32].

The benchmark included molecular descriptors spanning different dimensionalities and chemical information domains:

- 0D/1D descriptors: Constitutional descriptors capturing basic structural properties

- 1D fingerprints: MACCS 166 keys and Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs)

- 2D descriptors: CATS2 pharmacophore pairs and matrix-based descriptors

- 3D descriptors: WHIM and GETAWAY capturing three-dimensional molecular features

Performance was quantified using the Scaffold Diversity of Actives (SDA%) metric, calculated as:

$$S{D}_{A} \% =\frac{ns}{na}\cdot 100$$

where ns represents the number of unique Murcko scaffolds identified in the top 5% of the ranked list, and na is the number of actives present in that same portion [32].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Molecular Descriptors in Scaffold Hopping

| Molecular Representation | Dimensionality | Mean SDA% ± Standard Deviation | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHALES-DFTB+ | 3D + Electronic | 89 ± 9 | Best overall scaffold hopping |

| WHALES-GM | 3D + Electronic | 87 ± 10 | Balance of speed and performance |

| WHALES-shape | 3D Shape | 85 ± 11 | Pure shape similarity |

| GETAWAY | 3D | 84 ± 11 | Atom-weighted 3D descriptors |

| WHIM | 3D | 82 ± 12 | Principal axes molecular properties |

| CATS2 | 2D | 80 ± 13 | Pharmacophore pairs |

| Matrix-based descriptors | 2D | 78 ± 13 | Graph theory-based |

| MACCS FP | 1D | 75 ± 12 | 166 predefined substructures |

| ECFPs | 1D | 73 ± 12 | Atom-centered radial fragments |

| Constitutional descriptors | 0D/1D | 76 ± 13 | Basic molecular properties |

The benchmark results demonstrated that all three WHALES versions outperformed state-of-the-art methods in 89% of the tested biological targets, with WHALES-DFTB+ showing the highest scaffold-hopping ability [32]. This superior performance highlights WHALES' capacity to identify structurally diverse compounds that maintain similar bioactivity, a crucial capability in natural product-inspired drug design where structural complexity often necessitates simplification while retaining activity.

Prospective Application: Discovery of Novel RXR Modulators

The scaffold-hopping capability of WHALES was validated in a prospective application targeting the retinoid X receptor (RXR). Using known RXR modulators as queries, WHALES descriptors identified four novel agonists with innovative molecular scaffolds that populated previously uncharted regions of the chemical space [32].

Notably, one identified agonist possessed a rare non-acidic chemotype that exhibited:

- High selectivity across 12 nuclear receptors

- Comparable efficacy to bexarotene in inducing ABCA1 (ATP-binding cassette transporter A1)

- Effective induction of angiopoietin-like protein 4 and apolipoprotein E expression

This successful prospective application confirmed WHALES' ability to detect novel bioactive chemotypes through straightforward similarity searching, demonstrating its practical utility in hit identification and lead optimization campaigns [32].

Recent Application: hDAT-Targeted Drug Repurposing

A 2025 study further validated WHALES' utility in drug repurposing for the human dopamine transporter (hDAT). Researchers employed WHALES descriptors to identify novel atypical inhibitors that bind to hDAT's allosteric site, using four benztropine-like atypical inhibitors as templates [33].

The workflow encompassed:

- Similarity screening of 4,921 marketed and clinically tested drugs using WHALES

- ADMET prediction for 27 identified candidates

- Induced-fit docking to estimate binding affinities

- In vitro validation of six selected compounds

This integrated approach successfully identified three compounds with significant hDAT inhibitory potency (IC₅₀ values of 0.753 μM, 0.542 μM, and 1.210 μM, respectively), demonstrating WHALES' effectiveness in prospective drug discovery applications [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Virtual Screening with WHALES Descriptors

Purpose: To identify novel chemotypes with similar biological activity to a query compound through WHALES-based similarity searching.

Materials and Software:

- Chemical database: Collections such as ChEMBL, ZINC, or in-house compound libraries

- WHALES calculation code: Available from github.com/ETHmodlab/scaffoldhoppingwhales [31]

- 3D conformation generator: RDKit, OpenBabel, or similar cheminformatics toolkit

- Partial charge calculator: DFTB+ for high accuracy or Gasteiger-Marsili for rapid calculation [32]

Procedure:

- Query molecule preparation:

- Select a known active compound as the query structure

- Generate an energy-minimized 3D conformation using MMFF94 or similar force field

- Calculate partial charges using DFTB+ or Gasteiger-Marsili method

Database preparation:

- Curate database molecules by removing duplicates and undesirable compounds

- Generate 3D conformations for all database compounds

- Calculate partial charges using a consistent method

WHALES descriptor calculation:

- Compute WHALES descriptors for query and all database compounds

- Standardize descriptor values using z-score normalization if necessary

Similarity searching:

- Calculate similarity between query and database compounds using Euclidean or Mahalanobis distance

- Rank database compounds by descending similarity (or ascending distance)

- Apply scaffold analysis to identify diverse chemotypes in top rankings

Result analysis:

- Extract top-ranked compounds for visual inspection

- Calculate scaffold diversity metrics (SDA%) to evaluate scaffold-hopping performance

- Select promising candidates for experimental validation

Troubleshooting:

- If results show insufficient scaffold diversity, try WHALES-shape version to emphasize structural over electronic similarity

- If computational resources are limited, use Gasteiger-Marsili partial charges instead of DFTB+

- Ensure consistent protonation states for all compounds at physiological pH

Protocol 2: Natural Product-Inspired Scaffold Hopping

Purpose: To translate structural information from complex natural products to synthetically accessible compounds using WHALES descriptors.

Materials and Software:

- Natural product database: Such as COCONUT, NPASS, or in-house collections

- Synthetic compound library: Commercially available screening compounds or synthetically feasible virtual libraries

- WHALES descriptors with DFTB+ partial charges for maximum sensitivity [32]

Procedure:

- Natural product selection:

- Identify bioactive natural product with desired biological activity

- Generate representative 3D conformation accounting for conformational flexibility

- Calculate WHALES descriptors for the natural product

Synthetic library screening:

- Curate library of synthetically accessible compounds

- Compute WHALES descriptors for all library compounds

- Perform similarity search using natural product as query

Scaffold hopping analysis:

- Identify top-ranking synthetic compounds with high WHALES similarity

- Analyze Murcko scaffolds to confirm structural novelty compared to natural product

- Evaluate synthetic accessibility of identified hits

Hit validation:

- Select diverse chemotypes for experimental testing

- Prioritize compounds with favorable drug-like properties

- Validate biological activity through in vitro assays

Validation: In the proof-of-concept study, WHALES identified seven natural-product-inspired synthetic compounds that modulated the cannabinoid receptor, featuring innovative scaffolds compared to actives annotated in ChEMBL [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for WHALES Applications

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in WHALES Workflow | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFTB+ | Software | Calculates accurate partial charges for WHALES-DFTB+ | Freely available |

| Gasteiger-Marsili Method | Algorithm | Rapid partial charge calculation for large datasets | Implemented in RDKit, OpenBabel |

| MMFF94 Force Field | Parameter Set | Generates energy-minimized 3D conformations | Implemented in most cheminformatics packages |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Handles molecular I/O, conformation generation, and descriptor calculation | Open-source Python library |

| - WHALES Implementation | Code Repository | Complete code for WHALES calculation and screening | github.com/ETHmodlab/scaffoldhoppingwhales [31] |

| ChEMBL Database | Chemical Database | Source of bioactive compounds for benchmarking and queries | Publicly available |

| - Murcko Scaffold Analysis | Algorithm | Quantifies scaffold diversity in screening results | Implemented in RDKit |

| Ziconotide | Ziconotide (Prialt) | Ziconotide is a synthetic ω-conotoxin for research into chronic pain. It is a selective, non-opioid N-type calcium channel blocker. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Chloranil | Chloranil, CAS:118-75-2, MF:C6Cl4O2, MW:245.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

WHALES descriptors represent a significant advancement in molecular representation for scaffold hopping and natural product-inspired drug design. By simultaneously capturing molecular shape and charge distribution, WHALES enables efficient identification of structurally diverse compounds with similar biological activity, addressing a critical challenge in medicinal chemistry. The robust performance of WHALES across retrospective benchmarks and prospective applications highlights its value in hit identification and lead optimization workflows. As computational drug discovery continues to evolve, holistic representations like WHALES will play an increasingly important role in bridging the gap between complex natural product architectures and synthetically accessible therapeutic compounds.

Natural products (NPs) are invaluable resources for drug discovery, characterized by their intricate scaffolds and diverse bioactivities. However, their structural complexity often leads to undesirable properties such as toxicity, metabolic instability, or poor pharmacokinetic profiles [21]. Scaffold hopping has emerged as a critical strategy to overcome these limitations by designing molecules with novel core structures (scaffolds) that retain the desired biological activity of the original natural product [19]. This approach not only helps optimize drug-like properties but also facilitates the creation of novel chemical entities with freedom-to-operate advantages [24].