Natural Product Drug Discovery in 2025: A Comprehensive Guide to Principles, AI Integration, and Future Opportunities

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the modern principles of natural product (NP) drug discovery, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Natural Product Drug Discovery in 2025: A Comprehensive Guide to Principles, AI Integration, and Future Opportunities

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the modern principles of natural product (NP) drug discovery, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the renewed importance of NPs as a source of novel therapeutics, covering their historical foundations and exceptional structural diversity. The scope extends to the latest methodological advances, including the pivotal role of artificial intelligence (AI), in silico screening, and integrated workflows that are accelerating lead identification and optimization. The content also addresses key technical and regulatory challenges, offering strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. Finally, it examines contemporary validation techniques and the proven success of NPs in addressing complex diseases, particularly in oncology and antiparasitic therapy, synthesizing these insights to outline a forward-looking perspective for the field.

The Enduring Power of Nature's Pharmacy: History, Significance, and Chemical Diversity

The integration of natural products into modern therapeutic development represents a critical pathway for addressing complex medical challenges. This whitepaper examines the evolution from traditional medicine practices to evidence-based drug discovery, highlighting the continued relevance of natural products in contemporary pharmaceutical research. We present quantitative data on natural product applications, detailed experimental methodologies for their investigation, and visualization of key workflows that enable researchers to bridge traditional knowledge with modern scientific validation. Within the broader thesis of natural product drug discovery principles, this analysis demonstrates how ancient therapeutic wisdom, when investigated through rigorous scientific frameworks, continues to yield transformative treatments for malignancies, infectious diseases, and other conditions with significant unmet medical needs.

Natural products (NPs) and traditional medicinal knowledge have served as cornerstone resources in healthcare for millennia, with over 80% of the world's population relying on some form of traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine (TCIM) for primary health needs [1]. The World Health Organization recognizes the significant role of Traditional Medicine (TM) in global healthcare, noting that most member states have requested guidance on integrating evidence-based TCIM services into their healthcare systems [2]. This historical legacy continues to inform modern drug discovery, with natural products comprising approximately 41% (646/1562) of all new drug approvals between 1981 and 2014 [3].

The pharmaceutical industry's renewed interest in natural products stems from their unique structural characteristics that distinguish them from traditional small-molecule drug candidates. Natural products typically exhibit higher molecular mass, greater molecular rigidity, diverse chemical nature, and unique spatial arrangements including a greater number of sp³ carbon atoms [4]. These properties enhance their ability to target protein-protein interactions—a challenging area for conventional small molecules. Despite advances in combinatorial chemistry and computational design, natural products remain indispensable sources of novel bioactive compounds, with approximately 50% of current antibiotics derived from natural origins [4].

Historical Foundations and Contemporary Relevance

From Traditional Knowledge to Approved Therapeutics

Traditional healing systems have provided the initial observations that led to many foundational therapeutics. The journey from traditional remedy to approved pharmaceutical follows a consistent pattern: ethnobotanical observation → bioactivity confirmation → isolation of active compounds → structural modification → clinical development [5]. This pathway is exemplified by several landmark drugs:

Morphine, isolated from Papaver somniferum (opium poppy) in 1817, represents the first plant natural product to be isolated and remains a critical analgesic [4]. Paclitaxel, originally derived from Taxus brevifolia (Pacific yew), has become an essential chemotherapeutic for ovarian, breast, and lung cancers [5] [4]. The antimalarial artemisinin, discovered through investigation of traditional Chinese herbal remedies, has saved millions of lives worldwide [4].

Table 1: Historical Natural Products and Their Therapeutic Applications

| Natural Product | Natural Source | Traditional Use | Modern Therapeutic Application | Discovery Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphine | Papaver somniferum (Opium poppy) | Analgesic | Severe pain management | Isolated 1817 |

| Quinine | Cinchona officinalis bark | Fever reducer | Malaria treatment | Early 19th century |

| Salicin | Salix babylonica (Willow tree) | Pain, inflammation | Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) | Isolated 1828 |

| Paclitaxel | Taxus brevifolia (Pacific yew) | Not documented | Chemotherapy agent | Approved 1993 |

| Artemisinin | Artemisia annua | Fever | Malaria treatment | Isolated 1972 |

Quantitative Significance in Modern Medicine

Recent analyses confirm the continued importance of natural products in addressing contemporary health challenges. The NPASS database (2023 update) now contains quantitative activity data for approximately 43,200 natural products against ~7,700 biological targets, representing a 40% and 32% increase respectively from previous versions [6]. This expanding repository reflects the growing research interest in characterizing the therapeutic potential of natural compounds.

Cancer research has particularly benefited from natural product investigation. Globally, malignancies cause one in six mortalities, creating an urgent need for innovative therapeutic approaches [5]. Natural products like Vincristine and Vinblastine (isolated from Catharanthus roseus) have demonstrated profound efficacy in managing leukemia and Hodgkin's disease, establishing the critical role of plant-derived compounds in oncology [5]. The development of Trabectedin, originally isolated from the tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata and approved by the FDA in 2015, further exemplifies how marine natural products can yield effective anticancer medications [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Data on Natural Product Applications in Drug Discovery

| Parameter | Historical Data | Current Status (2023-2025) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| NP-derived FDA approvals (1981-2014) | 41% of all new drug approvals | N/A | Demonstrates historical impact |

| NPs with documented activity data | N/A | ~43,200 compounds | 40% increase from previous database |

| Molecular targets for NPs | N/A | ~7,700 targets | 32% increase from previous database |

| Species sources documented | N/A | ~94,400 NPs with species sources | 32% increase from previous database |

| Global population using TCIM | N/A | >80% in both low and high-income countries [1] | Drives continued research interest |

Modern Methodologies: From Field Collection to Clinical Application

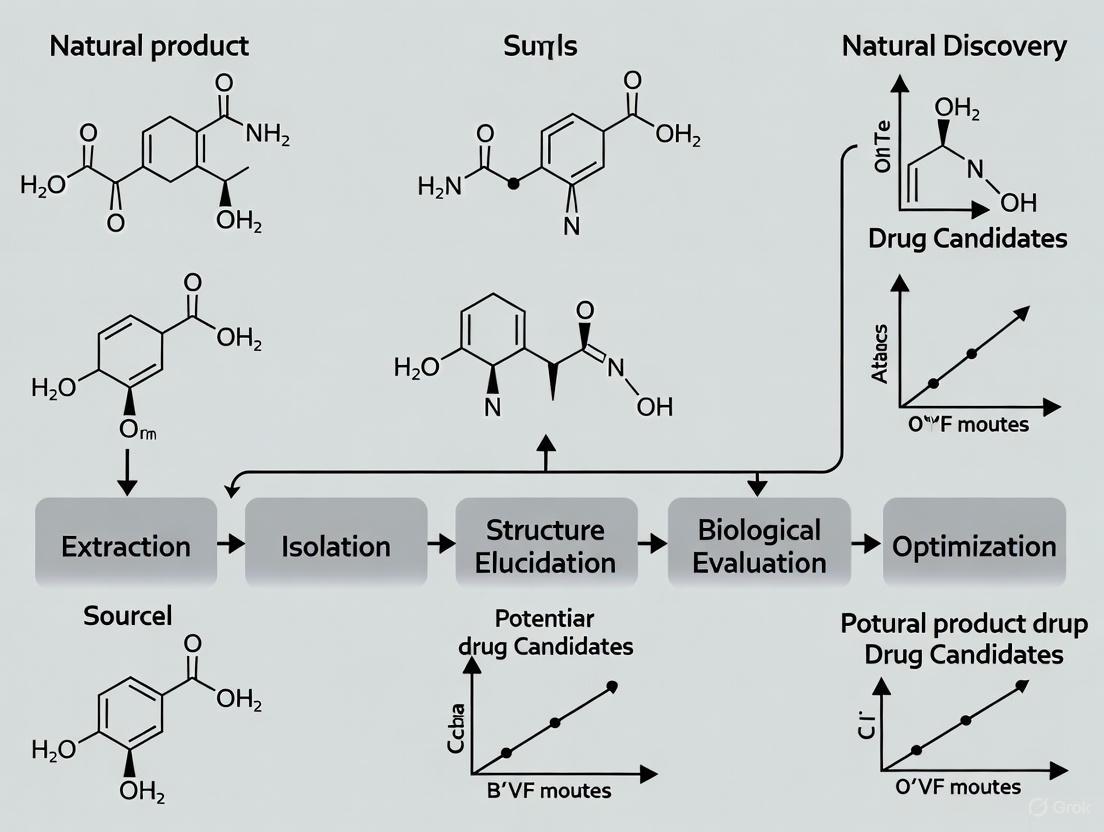

Integrated Discovery Workflow

The process of translating natural products from traditional remedies to modern therapeutics requires a multidisciplinary approach that integrates field biology, ethnopharmacology, analytical chemistry, and molecular biology. The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow:

Experimental Protocols for Natural Product Research

Bioactivity-Guided Fractionation Protocol

Objective: To isolate and identify bioactive compounds from crude natural extracts through iterative fractionation and biological screening.

Materials:

- Natural source material (plant, marine organism, microbial culture)

- Extraction solvents (methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate, water)

- Chromatography media (silica gel, C18, Sephadex LH-20)

- Bioassay systems (cellular, enzymatic, or phenotypic assays)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Air-dry and pulverize source material. Perform sequential extraction with solvents of increasing polarity (hexane → ethyl acetate → methanol → water).

- Primary Screening: Test crude extracts in relevant bioassays (e.g., cytotoxicity, antimicrobial activity, enzyme inhibition). Select active extracts for further investigation.

- Fractionation: Subject active crude extract to open-column chromatography or vacuum-liquid chromatography using appropriate stationary phases. Collect fractions based on TLC or HPLC monitoring.

- Secondary Screening: Test all fractions against the same bioassay to identify active fractions.

- Compound Isolation: Purify active fractions using techniques including preparative TLC, HPLC, or counter-current chromatography. Monitor purification using analytical HPLC.

- Structural Elucidation: Employ spectroscopic methods including NMR (¹H, ¹³C, 2D experiments), mass spectrometry, and X-ray crystallography to determine complete chemical structure.

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies: Synthesize structural analogs to identify critical functional groups for bioactivity [5] [4].

Computational Screening Protocol for Natural Product Libraries

Objective: To prioritize natural products for experimental testing through in silico prediction of bioactivity, drug-likeness, and target engagement.

Materials:

- Natural product compound libraries (e.g., NPASS database)

- Molecular docking software (AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD)

- ADMET prediction tools (SwissADME, admetSAR)

- Cheminformatics platforms (RDKit, OpenBabel)

Methodology:

- Library Curation: Compile natural product structures from databases such as NPASS, which contains >94,400 compounds with species source information [6].

- Virtual Screening: Perform molecular docking against protein targets of therapeutic interest. Use consensus scoring to improve prediction reliability.

- Drug-Likeness Evaluation: Apply filters including Lipinski's Rule of Five, Veber's rules, and quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED).

- ADMET Profiling: Predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties using in silico tools.

- Network Pharmacology Analysis: Construct compound-target-pathway networks to identify potential polypharmacology and mechanistic pathways.

- Hit Prioritization: Rank compounds based on integrated scores combining docking scores, drug-likeness, and ADMET properties [5] [7] [3].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for Natural Product Drug Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Product Databases | NPASS Database [6] | Quantitative activity and species source data | ~43,200 NPs with activity data, ~94,400 with species sources |

| CMAUP Database [6] | Collective molecular activities of useful plants | Plant-specific bioactivity data | |

| Analytical Instruments | High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) [4] | Precise molecular weight and structural information | High mass accuracy for compound identification |

| NMR Spectroscopy [4] | Structural elucidation of complex natural products | 1D and 2D experiments for complete structure determination | |

| Liquid Chromatography Systems [4] | Compound separation and purification | HPLC, UHPLC for analytical and preparative applications | |

| Bioassay Systems | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Platforms [8] | Rapid bioactivity assessment of compound libraries | Automated screening of thousands of compounds |

| Target-Based Assays [5] | Specific molecular target engagement | Enzyme inhibition, receptor binding assays | |

| Phenotypic Screening [5] | Functional responses in cellular systems | Cell viability, antimicrobial activity, functional changes | |

| Computational Tools | Molecular Docking Software [5] | Predicting protein-ligand interactions | Virtual screening of natural product libraries |

| ADMET Prediction Tools [5] | In silico pharmacokinetic and toxicity assessment | Early elimination of problematic compounds | |

| Chemical Similarity Tools [6] | Estimating bioactivity based on structural similarity | Chemical Checker for activity prediction |

Advanced Research Applications and Case Studies

Natural Products in Targeted Cancer Therapy

Natural products have found innovative applications in advanced therapeutic modalities, particularly in targeted cancer therapy. The development of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represents a paradigm shift in oncology treatment, combining the specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the potency of natural product-derived cytotoxic agents [8]. This approach minimizes systemic toxicity while maximizing tumor cell killing.

The diagram below illustrates how natural products are integrated into targeted therapeutic platforms:

Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives

The field of natural product drug discovery is undergoing rapid transformation through the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. These technologies are addressing historical challenges in NP research, including structural complexity, limited supply, and unknown mechanisms of action [8] [7]. AI algorithms can now predict bioactive natural products by analyzing structural similarities to known active compounds, significantly accelerating the discovery process [7] [9].

The emerging paradigm of data-driven drug discovery leverages large-scale repositories like the NPASS database to generate therapeutic hypotheses systematically rather than relying solely on traditional bioassay-guided approaches [3]. This methodology combines cheminformatics (molecular characterization), bioinformatics (target prediction), and knowledge engineering (literature mining) to create a comprehensive framework for identifying promising natural product candidates [3].

Future directions in natural product research include the development of advanced cultivation techniques for previously unculturable microorganisms, application of synthetic biology for sustainable production of complex natural products, and implementation of blockchain technology for ensuring ethical sourcing and equitable benefit-sharing with indigenous communities [1] [2]. The WHO's establishment of the Global Centre for Traditional Medicine in Jamnagar, India, further signals the growing recognition of natural products' role in addressing global health challenges [2].

Natural products (NPs) and their structural analogues have historically served as a major source of pharmacotherapeutic agents, particularly for cancer and infectious diseases [10]. These compounds, derived from terrestrial plants, marine organisms, and microorganisms, represent a critical foundation of drug discovery, providing unique structural diversity and biological pre-validation that synthetic libraries often lack [11]. The historical use of natural products in traditional medicine systems, documented since 2600 B.C. in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, provided the initial leads for many scientifically validated therapeutic agents [11]. Despite a temporary decline in interest from the pharmaceutical industry from the 1990s onward due to technical challenges in screening and optimization, recent technological advancements have revitalized NP-based drug discovery, making this field more relevant than ever for addressing contemporary medical challenges [10].

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive quantitative analysis of the substantial contribution of natural products to approved drugs, framing this discussion within the core principles of natural product drug discovery research. Through systematic data compilation and methodological exposition, we aim to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with both historical context and forward-looking perspectives on NP-based drug discovery. The integration of advanced methodologies—including artificial intelligence, high-throughput screening, chemical biology, and bioinformatics—is now positioning natural products for continued impact in tackling unmet medical needs, including antimicrobial resistance and complex chronic diseases [8].

Quantitative Analysis of Natural Product-Derived Pharmaceuticals

Historical and Contemporary Impact

The quantitative contribution of natural products to the pharmaceutical landscape is substantial and enduring. Analysis of the FDA-approved drug portfolio reveals that approximately 50% of all approved drugs are natural products or natural product derivatives [12]. This figure underscores the critical role that NPs continue to play in pharmacotherapy despite the rise of combinatorial chemistry and synthetic biology approaches. Between 1981 and 2014, natural products remained significant sources of new drugs, with particularly strong representation in anti-cancer and anti-infective categories [10].

The plant kingdom accounts for the majority of known natural products, with approximately 70% of compounds recorded in the Dictionary of Natural Products originating from botanical sources [13]. Certain plant families have been exceptionally prolific; the Leguminosae family alone has contributed 44 products that have received regulatory approval or advanced to clinical development [13]. As of December 2004, the FDA approved the first marine-derived compound, ziconotide intrathecal infusion (Prialt), for severe pain management, followed by the European Union's approval of trabectedin (Yondelis) in October 2007 as the first marine-derived anticancer drug [13]. These milestones highlight the expanding diversity of NP sources with therapeutic potential.

Table 1: Natural Product Contributions to Major Therapeutic Areas

| Therapeutic Area | Percentage of NP-Derived Drugs | Representative Examples | Year of First Approval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-infectives | >60% | Penicillins, Tetracyclines | 1940s |

| Anticancer Agents | ~40% | Paclitaxel, Trabectedin | 1990s |

| Immunosuppressants | ~30% | Cyclosporine, Rapamycin | 1980s |

| Central Nervous System | ~25% | Morphine, Reserpine | 1800s/1950s |

Molecular Properties and Drug-Likeness

Comparative analysis of molecular properties between natural products and FDA-approved drugs reveals both similarities and strategically important differences. The Universal Natural Products Database (UNPD), containing 197,201 unique natural products, provides a robust dataset for such comparisons [12]. Statistical analysis demonstrates that natural products exhibit larger mean values and standard deviations for key molecular descriptors compared to synthetic drugs, indicating greater structural complexity and diversity [12].

When evaluated against Lipinski's "Rule of Five" criteria for drug-likeness, 52.0% (102,605) of natural products in the UNPD comply with all four parameters, while 71.8% (141,628) satisfy at least three criteria [12]. This is comparable to the 77.17% of FDA-approved drugs that fully comply with the Rule of Five [12]. The chemical space occupied by natural products shows significant overlap with approved drugs but extends into regions associated with complex polypharmacology, providing opportunities for addressing challenging biological targets [12].

Table 2: Molecular Property Comparison: Natural Products vs. Approved Drugs

| Molecular Property | Natural Products (Mean) | FDA-Approved Drugs (Mean) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | 300-350 Da interval | 250-300 Da interval | p < 0.01 |

| AlogP | Wider distribution | Narrower distribution | p < 0.01 |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors | 3.21 ± 2.34 | 2.85 ± 2.16 | p < 0.05 |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptors | 6.02 ± 3.87 | 5.45 ± 3.24 | p < 0.05 |

| Rotatable Bonds | 4.78 ± 3.95 | 4.12 ± 3.56 | p < 0.05 |

| Aromatic Rings | 1.82 ± 1.45 | 2.15 ± 1.32 | p < 0.01 |

Methodological Framework for Natural Product Drug Discovery

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

The systematic investigation of natural products for drug discovery follows established workflows that integrate traditional knowledge with modern technological approaches. The standard methodology encompasses bioresource selection, extraction, bioactivity-guided fractionation, compound identification, and lead optimization [13].

Bioresource Selection and Authentication: The process begins with careful selection and taxonomic authentication of source material. Traditional medicinal knowledge often guides initial source selection, with the Ebers Papyrus (2900 B.C.) and Chinese Materia Medica (1100 B.C.) providing historical precedents for plant-based medicines [11]. Contemporary approaches combine this ethnobotanical knowledge with ecological considerations and biodiversity surveys.

Extraction and Fractionation: Sequential extraction using solvents of increasing polarity (hexane, ethyl acetate, methanol, water) provides preliminary fractionation based on compound polarity [12]. Advanced extraction techniques including supercritical fluid extraction, pressurized liquid extraction, and microwave-assisted extraction have improved efficiency and yield while reducing environmental impact [13]. The crude extract is typically subjected to bioactivity-guided fractionation using chromatographic methods including vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC), flash chromatography, and eventually high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Bioactivity Screening: Extracts and fractions are screened against relevant biological targets using in vitro assays. Modern approaches employ high-throughput screening (HTS) platforms, with recent technological developments enabling more efficient NP screening [10]. Phenotypic screening remains particularly valuable for NP discovery, as it detects bioactivity without requiring prior knowledge of specific molecular targets [10].

Structure Elucidation: Bioactive compounds are characterized using advanced analytical techniques, primarily hyphenated systems that combine separation with spectroscopic detection. Key methodologies include:

- LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) for molecular weight and fragmentation pattern analysis

- LC-NMR (Liquid Chromatography-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) for structural information

- HRMS (High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry) for precise molecular formula determination

- MS/MS (Tandem Mass Spectrometry) for structural elucidation through fragmentation patterns

Recent advances in analytical technologies, particularly improved NMR and mass spectrometry instrumentation, have significantly enhanced the pace and accuracy of NP structure elucidation [10].

Diagram 1: NP Drug Discovery Workflow

Dereplication Strategies

Dereplication represents a critical step in NP research to avoid redundant rediscovery of known compounds. This process combines chemical screening with database mining to rapidly identify previously characterized molecules [10]. Modern dereplication approaches utilize:

- Hyphenated Techniques: LC-UV-MS and LC-MS-SPE-NMR systems provide comprehensive chemical profiles

- Spectroscopic Databases: Mass spectral and NMR libraries enable rapid compound identification

- Cytoscape Analysis: Network visualization tools map compound-target relationships based on existing data

- In Silico Prediction: Computational models predict potential bioactivity based on structural features

The integration of these dereplication strategies has significantly improved the efficiency of NP discovery programs by focusing resources on novel chemical entities with potential therapeutic value [10].

Technological Advances Revolutionizing Natural Product Research

Analytical and Computational Innovations

Recent technological developments have addressed historical bottlenecks in NP-based drug discovery, revitalizing interest in this field [10]. Key advancements include:

Advanced Analytical Technologies: Hyphenated spectroscopic techniques have dramatically improved the pace and accuracy of NP structure elucidation. LC-HRMS-NMR systems now provide comprehensive structural information from limited quantities of material [10]. The implementation of Ultra High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) has enhanced separation efficiency, while new mass spectrometry approaches like ion mobility provide additional structural dimensions [10].

Genome Mining and Engineering: The ability to sequence and analyze the genomes of NP-producing organisms has revealed numerous cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters encoding potential novel compounds [10]. Heterologous expression and pathway engineering enable production of complex NPs in more tractable host organisms, addressing supply challenges associated with rare source organisms [10].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI algorithms now assist in multiple aspects of NP discovery, from predicting biosynthetic pathways to identifying potential molecular targets [8] [13]. Machine learning models trained on known NP structures and activities can prioritize compounds for experimental evaluation, accelerating the discovery process [8].

Chemical Biology Tools: Advanced target identification methods, including the highly accurate non-labeling chemical proteomics approach, enable deconvolution of NP mechanisms of action [8]. These techniques are particularly valuable for NPs with complex polypharmacology.

Emerging Therapeutic Modalities

Natural products are finding new applications in emerging therapeutic modalities, most notably as payloads in antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) [8]. The complex mechanism of action and high potency of many NPs make them ideal warheads for targeted delivery systems. Additionally, NP-derived hybrid molecules that combine natural scaffolds with synthetic elements represent a promising strategy for addressing complex diseases through multi-target engagement [8].

Diagram 2: Technological Advances in NP Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for NP Drug Discovery

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Key Advances |

|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Media | Sephadex LH-20, C18 silica, DIAION HP-20 | Size-exclusion and reverse-phase chromatography for compound isolation | Improved resolution and recovery rates |

| Analytical Standards | Natural product libraries (e.g., UNPD, CNPD) | Dereplication and compound identification | Expanded coverage of chemical space |

| Bioassay Systems | Cell-based phenotypic assays, enzyme inhibition assays | High-throughput bioactivity screening | Miniaturization and automation |

| Spectroscopic Platforms | LC-HRMS-NMR, UPLC-QTOF-MS, MS/MS | Structural characterization and elucidation | Enhanced sensitivity and resolution |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Cytoscape, GNPS, AntiMarin | Network pharmacology and target prediction | Integration of multi-omics data |

| Biosynthetic Tools | Heterologous expression systems, CRISPR-Cas9 | Pathway engineering and production optimization | Enables production of cryptic metabolites |

| Feruloylputrescine | Feruloylputrescine, CAS:501-13-3, MF:C14H20N2O3, MW:264.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Lactobionic Acid | Lactobionic Acid Reagent|C12H22O12|96-82-2 | High-purity Lactobionic Acid for research. Explore applications in biochemistry, cell culture, and preservative science. For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

The Universal Natural Products Database (UNPD), comprising 197,201 natural products from plants, animals, and microorganisms, represents one of the largest non-commercial freely available databases for natural products research [12]. This resource, combined with commercial compound libraries, provides essential reference materials for dereplication and identification workflows. Modern NP research increasingly relies on integrated platforms that combine multiple analytical techniques with computational tools for comprehensive metabolite profiling [10].

Network pharmacology approaches have gained prominence in NP research, recognizing that many natural products exert their therapeutic effects through multi-target mechanisms rather than single-target interactions [12]. Tools like Cytoscape enable visualization and analysis of complex compound-target-disease networks, providing insights into polypharmacology and systems-level effects of NP interventions [12].

Natural products continue to make substantial contributions to approved drugs, with approximately half of FDA-approved pharmaceuticals originating from natural sources or their derivatives [12]. This quantitative impact underscores the enduring importance of NPs in addressing human disease, particularly in therapeutic areas like oncology and infectious diseases where structural complexity and specific bioactivity are paramount [10]. The historical success of NPs is now being amplified by technological innovations across the discovery pipeline, from genome-informed sourcing to AI-accelerated screening and optimization [8].

Future NP research will be characterized by increased integration of multidisciplinary approaches, with chemical biology, synthetic biology, and computational methods playing expanding roles [8]. The application of highly accurate non-labeling chemical proteomics will enhance target identification for complex NPs, while continued development of expression platforms will address supply challenges [8]. Furthermore, the growing understanding of NP biosynthetic pathways enables bioengineering approaches to expand chemical diversity and optimize therapeutic properties [10].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the principles of natural product drug discovery research remain foundational: respect for traditional knowledge, commitment to rigorous scientific validation, and openness to technological innovation. By embracing these principles while leveraging emerging tools and methodologies, the scientific community can continue to harness the substantial potential of natural products to address evolving medical needs and deliver novel therapeutics to patients worldwide.

Natural products (NPs) exhibit exceptional structural diversity that enables them to occupy chemical spaces largely inaccessible to synthetic compounds. This review examines the distinctive structural complexity, diverse biosynthetic origins, and broad bioactivity of NPs through a chemoinformatics lens. With over 1.1 million documented compounds, NPs display remarkable molecular complexity, frequent glycosylation, and unique halogenation patterns that contribute to their privileged status in drug discovery. Analysis reveals that over 50% of approved small-molecule drugs originate directly or indirectly from natural products, underscoring their profound pharmaceutical significance. This comprehensive analysis synthesizes current understanding of NP chemical space, providing researchers with methodological frameworks for exploring this diversity and highlighting emerging opportunities in pseudo-natural product design and extreme environment bioprospecting.

Natural products represent the evolved chemical defense, signaling, and regulatory systems of living organisms that have been refined through millions of years of evolutionary selection. This extensive optimization process has yielded compounds with exceptional structural diversity and biological relevance. The chemical space of NPs is distinguished by greater structural complexity compared to synthetic molecules, featuring more stereocenters, higher molecular rigidity, and increased oxygen content [14]. These characteristics enable NPs to interact with diverse biological targets through complex three-dimensional binding modes that often evade synthetically designed compounds.

The pharmaceutical significance of NPs is substantial, with analyses indicating that 39% of marketed drugs originate from natural products and their derivatives—comprising 10% unaltered natural products and 29% semi-synthetic derivatives [15]. Between 1981 and 2014, over 50% of newly developed drugs were developed from NPs, particularly in therapeutic areas including oncology, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular disorders [16] [17]. This remarkable success rate stems from the evolutionary optimization of NPs for biological interactions, positioning them as invaluable resources for drug discovery scaffolds and lead compounds.

Structural Characteristics of Natural Products

Molecular Complexity and Three-Dimensionality

Natural products exhibit substantially greater molecular complexity than their synthetic counterparts, a characteristic that directly influences their biological activity and target selectivity. Statistical analyses reveal that NPs contain a higher density of stereogenic centers, with approximately 70-91% of compounds in various databases containing defined stereochemistry [16] [17]. This stereochemical complexity enables sophisticated three-dimensional binding to biological targets, a property increasingly recognized as crucial for drug specificity.

The ring systems in NPs demonstrate exceptional diversity and complexity compared to synthetic compounds. Natural products frequently incorporate polycyclic systems with bridgehead atoms and complex ring fusions that create rigid, pre-organized three-dimensional structures [14]. This structural rigidity reduces the entropic penalty upon binding to biological targets, enhancing binding affinity and specificity. Additionally, NPs exhibit a wider variety of ring sizes and heteroatom incorporations, contributing to their distinct pharmacophoric properties.

Functional Group Diversity and Modifications

Natural products display distinctive patterns of functionalization that contribute to their biological activities and physicochemical properties. One particularly notable characteristic is their high oxygen content relative to synthetic compounds, manifested through abundant hydroxyl, carbonyl, and ether functionalities [14]. This oxygen-rich composition enhances hydrogen-bonding capacity and influences solubility profiles.

Glycosylation represents another distinctive feature of NPs, with approximately 30% of all natural products containing sugar moieties [14]. These carbohydrate modifications profoundly influence bioavailability, target recognition, and pharmacokinetic properties. Additionally, NPs exhibit unique halogenation patterns, with marine natural products particularly enriched in bromine and chlorine substituents—modifications that often enhance membrane permeability and receptor binding affinity.

Table 1: Key Structural Differentiators Between Natural Products and Synthetic Compounds

| Structural Feature | Natural Products | Synthetic Compounds | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stereocenters | High density (70-91% have defined stereochemistry) | Limited | Enhanced target specificity |

| Ring Systems | Complex polycyclic frameworks | Simpler monocyclic/bicyclic | Pre-organized 3D structure |

| Oxygen Content | High (hydroxyl, carbonyl, ether) | Moderate | Improved hydrogen bonding |

| Glycosylation | ~30% of compounds | Rare | Solubility and recognition |

| Halogenation | Unique patterns (Br, Cl in marine NPs) | Standard patterns (F, Cl) | Membrane permeability |

Quantitative Analysis of Natural Product Chemical Space

Databases and Collections: Mapping the Chemical Universe

The comprehensive mapping of NP chemical space relies on extensive databases and collections that document structural and biological information. Current estimates indicate that over 1.1 million natural products have been documented across various databases [14]. However, a significant accessibility challenge exists, with only approximately 10% of known NPs being readily obtainable for experimental testing from commercial vendors and public research institutions [18] [14].

The landscape of NP databases includes over 120 different resources published since 2000, with 98 remaining accessible and only 50 providing open access [16] [17]. Among the most significant comprehensive collections is COCONUT (COlleCtion of Open NatUral prodUcTs), which contains structures and annotations for over 400,000 non-redundant NPs, representing the largest open collection available [16] [17]. Commercial databases provide additional coverage, with the Dictionary of Natural Products containing extensive curated entries, and resources like SciFinder and Reaxys encompassing over 200,000-300,000 natural compounds each [16].

Table 2: Major Natural Product Databases and Their Characteristics

| Database Name | Type | Size (Compounds) | Access | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COCONUT | Generalistic | >400,000 | Open | Largest open collection, non-redundant |

| Dictionary of Natural Products | Generalistic | ~250,000 | Commercial | Comprehensive, well-curated |

| SciFinder | Chemicals | >300,000 NPs | Commercial | Extensive curated content |

| Reaxys | Chemicals | >200,000 NPs | Commercial | Reaction and substance data |

| MarinLit | Marine | >30,000 | Commercial | Marine-specific, highly curated |

| AntiBase | Microbial | >40,000 | Commercial | Microbial NPs with metadata |

Comparative Chemical Space Analysis

Chemoinformatic analyses reveal that natural products occupy a broader chemical space than synthetic compounds, with distinct clustering in regions associated with biological relevance [14]. This expanded coverage is particularly evident in physicochemical property distributions, where NPs exhibit higher molecular weights, greater numbers of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, and increased molecular rigidity compared to synthetic medicinal chemistry compounds.

The readily obtainable subset of NPs demonstrates exceptional diversity, populating regions of chemical space highly relevant to drug discovery despite representing only a fraction of known natural products [18]. Significant differences exist in the coverage of chemical space by individual databases, with specialized resources focusing on particular organismal sources (marine, microbial, plant) or structural classes (alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids) that collectively provide comprehensive coverage of NP chemical space.

Methodological Framework for Natural Product Chemical Space Analysis

Computational Approaches and Workflows

The systematic analysis of NP chemical space requires specialized computational approaches that address the unique challenges of natural product structures. A critical first step involves the development and application of algorithms like "SugarBuster" for the removal of sugars and sugar-like moieties from natural products, enabling focused analysis of the aglycone scaffolds that often represent the core pharmacophoric elements [18].

Rule-based automated classification systems enable the organization of NPs into natural product classes (alkaloids, steroids, flavonoids, etc.), facilitating chemotaxonomic analyses and structure-activity relationship studies [18]. These classification systems typically leverage structural fingerprints, molecular descriptors, and machine learning approaches to categorize compounds based on their biosynthetic origins and structural characteristics.

Experimental Validation and Structure Elucidation

Beyond computational analysis, comprehensive NP chemical space exploration requires sophisticated experimental approaches for structural characterization and bioactivity validation. More than 2000 natural products have been characterized through X-ray crystallography in complex with biomacromolecules, providing crucial structural insights into their molecular interactions [18].

Advanced spectroscopic techniques, particularly NMR and mass spectrometry, play essential roles in NP structure elucidation. Databases such as NIST mass spectral libraries contain over 250,000 molecules of natural origin, enabling comparative analyses and dereplication [16]. The integration of these experimental datasets with computational chemical space analysis creates powerful workflows for identifying novel scaffolds and predicting bioactivities.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for NP Chemical Space Exploration

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Databases for NP Chemical Space Analysis

| Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SugarBuster Algorithm | Computational Tool | Removes sugar moieties from NPs | Focused aglycone scaffold analysis |

| COCONUT Database | Open Database | Provides 400,000+ NP structures | Virtual screening, chemoinformatics |

| Dictionary of Natural Products | Commercial Database | Authoritative NP structural data | Structure classification, validation |

| NIST Mass Spectral Library | Spectral Database | NP identification by mass spectrometry | Dereplication, structure elucidation |

| Rule-Based Classification System | Computational Method | Automates NP class assignment | Chemotaxonomy, chemical space organization |

| Crystallography Data (PDB) | Structural Data | NP-biomolecule complex structures | Interaction studies, target engagement |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

The continued expansion of NP chemical space relies on the exploration of underexplored biological sources and extreme environments. Marine organisms, particularly those from deep-sea and hydrothermal vent ecosystems, produce NPs with novel scaffolds and potent bioactivities not found in terrestrial organisms [14]. These environments exert unique evolutionary pressures that shape distinct biosynthetic pathways, resulting in natural products with enhanced chemical novelty.

Microorganisms from extreme environments (extremophiles) represent another promising frontier for chemical space expansion. These organisms produce NPs adapted to function under conditions of extreme temperature, pressure, salinity, or pH, resulting in structures with exceptional stability and unique mechanisms of action [14]. Systematic bioprospecting of these environments continues to yield chemically and biologically novel compounds.

Artificial Intelligence and Novel Methodologies

Artificial intelligence approaches are revolutionizing NP chemical space exploration through enhanced pattern recognition, bioactivity prediction, and novel scaffold design. Machine learning algorithms can identify complex relationships between structural features and biological activities across vast NP datasets, enabling predictive bioactivity modeling and target identification [14].

The emerging field of pseudo-natural products (PNPs) represents a promising methodological advancement that combines NP fragments in novel arrangements not accessible through biosynthetic pathways [19]. These hybrid structures bridge distinct regions of chemical space, creating compounds that retain the biological relevance of NPs while exhibiting enhanced structural novelty. Biology-oriented synthesis (BIOS) principles guide the rational design of these compounds, creating novel chemotypes with potential for unprecedented biological activities.

The exceptional structural diversity of natural products constitutes a unique chemical space that remains indispensable for drug discovery and chemical biology. This diversity stems from evolutionary optimization across millions of years, resulting in complex molecular architectures with privileged biological activities. Despite the challenges of accessibility and redundancy, NPs continue to provide novel scaffolds and lead compounds, with emerging technologies enhancing our ability to explore and leverage this chemical universe. The integration of traditional approaches with innovative methodologies—including extreme environment bioprospecting, artificial intelligence, and pseudo-natural product design—ensures that natural products will continue to serve as essential resources for addressing unmet medical needs and expanding the frontiers of chemical space.

Natural products and their derivatives have been a cornerstone of drug discovery, providing indispensable therapeutic agents for combating infectious diseases. The journeys of artemisinin, quinine, and ivermectin from natural sources to clinical application exemplify the profound impact of this approach. These compounds, sourced from the sweet wormwood plant (Artemisia annua), the bark of the cinchona tree, and the soil-dwelling bacterium Streptomyces avermitilis, respectively, have saved millions of lives and revolutionized the treatment of parasitic diseases. This whitepaper details their discovery, mechanistic principles, and experimental methodologies, framing their development within the core principles of natural product drug discovery research to inform and guide contemporary scientific efforts.

Artemisinin: A Modern Antimalarial Powerhouse

Discovery and Clinical Impact

Artemisinin is a sesquiterpene lactone isolated from Artemisia annua, a plant used in traditional Chinese medicine for fever [20]. Its discovery and development mark a triumph of modern pharmacognosy. It and its derivatives (e.g., artesunate, artemether) form the foundation of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), which the World Health Organization recommends as the first-line treatment for Plasmodium falciparum malaria [20]. The implementation of ACTs has contributed to a significant reduction in the global malaria burden.

Beyond malaria, recent clinical research highlights the therapeutic potential of artemisinin and its derivatives in other areas, including anti-parasitic (non-malaria), anti-tumor, and anti-inflammatory applications, demonstrating a promising safety profile in clinical trials [20].

Mechanism of Action

Artemisinin's anti-malarial activity is attributed to its unique endoperoxide bridge. Upon entry into the parasite-infected red blood cell, this bridge is cleaved by intra-parasitic ferrous iron (Fe²âº), leading to the generation of cytotoxic carbon-centered radicals [21]. These radicals alkylate and damage key parasitic macromolecules, including proteins and membranes, ultimately leading to parasite death.

Key Experimental Workflow and Methodologies

A pivotal advancement in artemisinin supply was achieved through synthetic biology and metabolic engineering.

Objective: Engineer a microbial host to produce artemisinic acid, a direct precursor to artemisinin, to ensure a stable and scalable supply independent of plant cultivation [22].

Protocol:

- Gene Identification and Isolation: Identify the genes encoding the enzymes of the artemisinin biosynthetic pathway from Artemisia annua, including the amorpha-4,11-diene synthase (ADS) and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP71AV1).

- Vector Construction and Transformation: Clone these genes into expression vectors suitable for a microbial host, initially E. coli and later the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

- Host Engineering (in Yeast):

- Upstream Pathway Enhancement: Engineer the native yeast mevalonate pathway to increase the supply of isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), the universal terpenoid precursors.

- Heterologous Pathway Expression: Introduce the genes for ADS and CYP71AV1 to convert FPP to artemisinic acid.

- Cofactor Optimization: Modify host metabolism to support the required cytochrome P450 activity.

- Fermentation and Extraction: Grow the engineered yeast in large-scale bioreactors. Extract artemisinic acid from the fermentation broth.

- Chemical Conversion: Semi-synthetically convert the microbially produced artemisinic acid to dihydroartemisinin, which can then be derivatized into final drugs like artesunate and artemether [22].

The following diagram visualizes this engineered metabolic pathway in yeast.

Diagram 1: Engineered Artemisinin Pathway in Yeast. Heterologous enzymes ADS and CYP71AV1 are introduced into yeast to convert the endogenous precursor FPP into artemisinic acid.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Artemisinin Research and Production

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research/Production |

|---|---|

| Artemisia annua Plant Material | Source of native biosynthetic genes for pathway identification and cloning [20]. |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Engineered microbial host for the heterologous production of artemisinic acid [22]. |

| Fermentation Bioreactor | System for the scalable, industrial-scale cultivation of engineered yeast [22]. |

| Artemisinin-Specific Antibodies | Key reagents for developing immunoassays (e.g., ELISA) for the quantification of artemisinin in samples. |

Ivermectin: A Broad-Spectrum Antiparasitic from the Soil

Discovery and Clinical Impact

Ivermectin, a derivative of avermectin, originates from the soil actinomycete Streptomyces avermitilis discovered by Satoshi ÅŒmura at the Kitasato Institute [23] [24]. This discovery, which earned ÅŒmura and William Campbell the 2015 Nobel Prize, yielded the first endectocide, effective against a wide range of internal and external parasites [24]. It is on the WHO's List of Essential Medicines.

Ivermectin's impact on global health is monumental, primarily through donation programs. It is the primary tool in global campaigns to eliminate onchocerciasis (river blindness) and lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis), with hundreds of millions of people treated annually [23] [24]. It is also effective against strongyloidiasis, scabies, and ascariasis [25].

Mechanism of Action

Ivermectin exerts its potent antiparasitic effect by binding with high affinity to glutamate-gated chloride channels (GluCls) in the nerve and muscle cells of invertebrates [24]. This binding potentiates the influx of chloride ions, leading to hyperpolarization of the cell membrane. The hyperpolarization blocks neuronal signaling and causes paralytic immobilization of the pharyngeal muscle and somatic body wall, leading to parasite death [24]. Its high safety margin in mammals is due to the absence of glutamate-gated chloride channels and its poor penetration of the blood-brain barrier [24].

Key Experimental Workflow and Methodologies

The discovery of ivermectin is a paradigm for successful natural product screening.

Objective: Discover novel bioactive compounds from soil-derived microorganisms with anthelmintic properties.

Protocol:

- Sample Collection and Strain Isolation: Collect soil samples from diverse environments. Isolate pure microbial strains, primarily actinomycetes, on selective culture media.

- In vitro Bioactivity Screening: Ferment isolated strains in liquid culture and prepare crude extracts. Screen extracts using in vitro assays against target parasites (e.g., the nematode Nippostrongylus brasiliensis).

- In vivo Validation: Administer promising crude extracts to parasite-infected model animals (e.g., mice, sheep) to confirm in vivo efficacy and safety.

- Bioassay-Guided Fractionation: Fractionate the active crude extract using chromatographic techniques (e.g., HPLC). Test each fraction for bioactivity, iteratively purifying the active component until a pure compound (avermectin) is isolated.

- Structural Elucidation: Determine the chemical structure of the active compound using spectroscopic methods (NMR, MS).

- Chemical Derivatization: Chemically modify the natural compound (e.g., selective hydrogenation to create ivermectin) to improve safety and efficacy profile [23] [24].

Diagram 2: Ivermectin Drug Discovery Workflow. The process from soil sampling to the development of ivermectin, heavily reliant on bioactivity-guided purification.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Ivermectin Research and Production

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research/Production |

|---|---|

| Streptomyces avermitilis | The producing microorganism; source of the avermectin gene cluster for fermentation [23]. |

| Model Nematodes (e.g., Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, Haemonchus contortus) | Used in in vitro and in vivo bioassays for anthelmintic activity screening [24]. |

| GluCl Channel Protein | Target protein for in vitro binding studies and mechanism of action investigations [24]. |

| Fermentation Media (Complex) | Supports the growth of S. avermitilis and the production of avermectins during fermentation [23]. |

Quinine: The Prototype Antimalarial

Discovery and Clinical Impact

Quinine, a quinoline alkaloid isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree, was the first chemical compound used for treating an infectious disease—malaria [26]. For centuries, it was the primary treatment for malaria until the emergence of resistance and newer drugs. Its use is now largely restricted to severe, chloroquine-resistant malaria when artesunate is not available [27] [26]. The FDA has banned its use for leg cramps due to the risk of serious side effects [27].

Mechanism of Action

While its precise mechanism is complex, quinine is known to accumulate in the parasite's food vacuole. It inhibits the detoxification of heme, a toxic byproduct of hemoglobin digestion. The drug is believed to bind to heme, preventing its polymerization into non-toxic hemozoin. This leads to the buildup of toxic heme, which damages the parasite's membranes and leads to its death.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Three Natural Product-Derived Drugs

| Parameter | Artemisinin | Ivermectin | Quinine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Source | Artemisia annua (plant) | Streptomyces avermitilis (bacterium) | Cinchona spp. (tree bark) |

| Drug Class | Sesquiterpene lactone | Macrocyclic lactone | Quinoline alkaloid |

| Primary Indication | Malaria (especially falciparum) | Onchocerciasis, Lymphatic Filariasis | Severe/Resistant Malaria |

| Molecular Target | Fe²⺠(activates endoperoxide bridge) | Glutamate-gated Chloride Channels (GluCls) | Heme Polymerization (in food vacuole) |

| Global Health Impact | ACTs are first-line malaria treatment; millions of courses distributed annually. | >1 billion treatments donated; key to eliminating river blindness & elephantiasis [24]. | Historical prototype; now a reserve drug. |

| Supply Source | Plant extraction & Synthetic Biology (yeast) [22]. | Industrial fermentation of S. avermitilis [23]. | Primarily plant extraction & chemical synthesis. |

The stories of artemisinin, ivermectin, and quinine underscore the enduring value of natural products in drug discovery. They highlight diverse success models: quinine as the historical prototype, artemisinin as a modern plant-derived drug enhanced by synthetic biology, and ivermectin as a microbial product deployed through unprecedented philanthropic partnership. Their development required a multidisciplinary convergence of microbiology, chemistry, pharmacology, and, increasingly, genetic engineering. For researchers, these case studies validate that investigating natural compounds, coupled with innovative technologies and sustainable supply strategies, remains a powerful approach for addressing unmet medical needs and combating global health challenges.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most severe global public health threats of the 21st century, directly causing an estimated 1.27 million deaths annually and contributing to nearly 5 million more [28]. This crisis undermines the foundation of modern medicine, rendering life-saving treatments—including routine surgeries, cancer chemotherapy, and organ transplantation—increasingly risky [28]. The emergence and spread of drug-resistant pathogens are accelerated by human activities, primarily the misuse and overuse of antimicrobials in human medicine, animal agriculture, and crop production [28]. Despite increasing recognition of the problem, the antibacterial development pipeline remains inadequate, creating significant unmet medical needs, particularly for infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) gram-negative bacteria [29] [30].

Within this challenging landscape, natural products (NPs) are experiencing a renaissance in drug discovery. Historically, NPs have been a vital source of therapeutic agents, and they offer unique chemical structures and biological activities that are increasingly viewed as potential solutions to combat resistant pathogens [8] [31]. This whitepaper examines the current drivers of AMR within a One Health framework, analyzes the most pressing unmet therapeutic needs, and details how modern natural product research—powered by advanced technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), high-throughput screening, and synthetic biology—is providing innovative strategies to address this escalating crisis [8] [32].

Global AMR Landscape and Key Drivers

The scale of the AMR threat is reflected in recent global surveillance data. The World Health Organization's (WHO) Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS), in its 2025 report, analyzed data from 110 countries between 2016 and 2023, encompassing over 23 million bacteriologically confirmed infections [33]. The findings present an alarming picture of resistance prevalence across common bacterial pathogens.

Table 1: Global AMR Prevalence for Key Pathogen-Antibiotic Combinations

| Pathogen | Antibiotic Class | Reported Resistance Rate | Primary Infection Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Third-generation cephalosporins | 42% (median across 76 countries) | Urinary Tract Infections, Bloodstream Infections [28] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Methicillin (MRSA) | 35% (median across 76 countries) | Bloodstream Infections, Skin and Soft Tissue Infections [28] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Carbapenems | Increasingly observed across multiple regions | Bloodstream Infections, Pneumonia [28] |

| E. coli (Urinary) | Fluoroquinolones | 1 in 5 cases show reduced susceptibility | Urinary Tract Infections [28] |

The economic costs of AMR are equally staggering, with the World Bank estimating that AMR could result in US$1 trillion in additional healthcare costs by 2050 and US$1 trillion to US$3.4 trillion in annual GDP losses by 2030 [28]. These figures underscore that AMR is not only a health crisis but also a fundamental threat to global economic stability.

One Health Drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance

AMR is a quintessential "One Health" issue, with its drivers and consequences inextricably linked to human, animal, and environmental health.

Human Health Sector: Inappropriate and excessive use of antibiotics in human medicine remains a primary driver. This includes over-prescription, use of broad-spectrum agents when narrower alternatives are suitable, and inadequate adherence to treatment protocols [32] [28]. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated this problem through increased antibiotic usage during the crisis [34].

Veterinary and Agricultural Sectors: Global veterinary antibiotic consumption was approximately 81,000 tons in 2018, with projections indicating a rise to 104,079 tons by 2030 [34]. Tetracyclines and penicillins constitute the bulk of this consumption, accounting for 40.5% and 14.1% respectively. Such massive use, particularly for non-therapeutic purposes like growth promotion, selects for resistant bacteria that can transfer through the food chain to humans [34] [32].

Environmental Sector: Environmental reservoirs, including wastewater treatment plants, surface water, and soil, are critical conduits for the dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [32]. Pharmaceutical manufacturing waste and agricultural runoff further contaminate ecosystems, creating hotspots for the horizontal gene transfer of resistance determinants between environmental and clinically relevant bacteria [34] [32].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnectedness of these drivers and the flow of resistance elements across the One Health spectrum.

Unmet Medical Needs and Resistance Mechanisms

Prioritized Unmet Needs in Antibacterial Therapy

From a clinical perspective, the infectious diseases community has identified clear areas of unmet need where effective therapeutic options are dwindling or non-existent. A survey of the Emerging Infections Network (EIN) found that front-line physicians view multidrug-resistant (MDR) gram-negative bacilli as the most severe unmet medical need, scoring higher (mean score 4.6/5) than MRSA, MDR tuberculosis, and MDR gonorrhea [29]. The same survey highlighted that the limited number of new antimicrobials under development was perceived as the greatest challenge (mean score 4.7/5) [29]. Clinicians are increasingly encountering infections resistant to all available antibacterial agents, with 63% of surveyed infectious disease specialists reporting caring for such a patient in the previous year [29].

Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance

At the microbial level, resistance arises through several well-characterized genetic and physiological mechanisms, which are often combined within a single bacterial cell to create MDR phenotypes.

Enzymatic Inactivation: Production of enzymes that degrade or modify antibiotics is a widespread resistance strategy. This includes extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases (e.g., KPC, NDM, OXA-48), which hydrolyze β-lactam antibiotics, rendering them ineffective [32].

Target Modification: Mutations in chromosomal genes can alter the drug target site, reducing antibiotic binding affinity. Examples include mutations in gyrA/parC genes for fluoroquinolones and rpoB for rifampicin [32].

Efflux Pumps: Overexpression of multidrug efflux systems (e.g., AcrAB–TolC in E. coli, MexAB–OprM in P. aeruginosa) actively pumps antibiotics out of the bacterial cell, decreasing intracellular drug concentration [32].

Reduced Permeability: Loss of porins (outer membrane proteins) in Gram-negative bacteria limits the entry of antibiotics into the cell, a mechanism particularly associated with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales [32].

Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT): The rapid dissemination of resistance is primarily fueled by HGT via plasmids, transposons, and integrons. These mobile genetic elements can carry multiple resistance genes simultaneously, leading to the emergence of "pan-resistant" pathogens in clinical settings [32]. The co-selection of resistance genes, such as carbapenemase and colistin resistance genes on a single plasmid, compresses the available last-line treatment options [32].

The diagram below summarizes these core resistance mechanisms and their functional consequences.

Natural Product Drug Discovery: Methodologies and Workflows

The complex chemical structures of natural products, evolved for specific biological functions, make them ideal starting points for tackling sophisticated bacterial resistance mechanisms. Modern NP discovery has moved beyond traditional bioassay-guided fractionation to incorporate a suite of advanced technologies.

Key Experimental Protocols in NP Discovery

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of Natural Product Libraries

- Objective: To rapidly identify novel bioactive compounds with antibacterial activity from large NP libraries.

- Methodology:

- Library Preparation: Utilize prefractionated natural product extracts or purified compound libraries in 96- or 384-well microtiter plates.

- Bacterial Strain Selection: Employ reference strains and clinically relevant MDR pathogens (e.g., MRSA, ESBL-producing E. coli, carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae).

- Growth Inhibition Assay: Inoculate wells with a standardized bacterial suspension (~5 x 10^5 CFU/mL) in Mueller-Hinton broth. Incubate for 16-20 hours at 35°C.

- Detection: Measure optical density (OD600) or use resazurin-based fluorescent dyes to quantify bacterial growth inhibition.

- Hit Validation: Confirm activity in dose-response assays to determine Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) against a broader panel of resistant pathogens [8] [31].

Protocol 2: Genome Mining for Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)

- Objective: To computationally identify the genetic potential of microorganisms to produce novel natural products.

- Methodology:

- Genome Sequencing: Perform whole-genome sequencing of microbial isolates using Illumina or PacBio platforms.

- BGC Identification: Analyze sequenced genomes with bioinformatics tools (e.g., antiSMASH, PRISM) to detect BGCs for known classes (e.g., non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), polyketide synthases (PKS), ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs)).

- Heterologous Expression: Clone silent or poorly expressed BGCs into suitable expression hosts (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor) to activate the production of cryptic metabolites.

- Compound Isolation and Structure Elucidation: Purify expressed metabolites using HPLC and characterize structures via NMR and MS/MS spectroscopy [8].

Protocol 3: AI-Guided Prediction of NP Targets and Mechanisms

- Objective: To predict the molecular targets and mechanisms of action of novel NPs using artificial intelligence.

- Methodology:

- Data Curation: Compile training datasets from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL, DrugBank) containing NP structures, bioactivity data, and known targets.

- Model Training: Develop machine learning models (e.g., graph neural networks, random forests) to learn complex structure-activity relationships.

- Target Prediction: Input novel NP structures into trained models to predict potential protein targets (e.g., bacterial topoisomerases, cell wall synthesis enzymes).

- Experimental Validation: Confirm predicted targets through in vitro binding assays (e.g., surface plasmon resonance) and phenotypic profiling (e.g., cytological profiling) [8] [31].

The integrated workflow for modern natural product discovery, from sourcing to lead optimization, is depicted below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for NP-Based AMR Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in NP Discovery | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Prefractionated NP Libraries | Provides diverse chemical starting points for screening; reduces complexity of crude extracts. | Identification of novel scaffolds against MDR Gram-negative pathogens [8]. |

| Genome Mining Software (e.g., antiSMASH) | Predicts Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) in microbial genomes to prioritize strains for compound discovery. | Discovery of novel lipopeptide antibiotics with activity against vancomycin-resistant bacteria [8]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Enables genetic manipulation of NP-producing strains to elucidate biosynthesis pathways and engineer overproduction. | Activation of silent gene clusters in Streptomyces species [32]. |

| LC-MS/MS & NMR Platforms | Enables dereplication (identification of known compounds) and structural elucidation of novel bioactive NPs. | Determination of chemical structure and purity of a new macrocyclic antibiotic [8] [31]. |

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) Platforms | Predicts NP bioactivity, molecular targets, and mechanisms of action; optimizes pharmacokinetic properties. | In silico prediction of a natural product's ability to inhibit bacterial efflux pumps [8]. |

| Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC) Platforms | Facilitates targeted delivery of potent NP-derived payloads to specific bacterial or host cells. | Development of monoclonal antibodies conjugated to NP-derived cytotoxins for targeted cancer therapy related to infections [8]. |

| 7-Hydroxyguanine | 7-Hydroxyguanine, CAS:16870-91-0, MF:C5H5N5O2, MW:167.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dioxo(sulphato(2-)-O)uranium | Dioxo(sulphato(2-)-O)uranium, CAS:16984-59-1, MF:C2H2O6U, MW:362.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Addressing the multifaceted crisis of AMR requires a unified strategy that aligns innovative scientific discovery with robust policy and stewardship. The One Health approach provides the essential framework, recognizing that the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems is interconnected. The integration of advanced natural product research into this framework offers a promising path forward. By leveraging cutting-edge technologies—from genome mining and AI to synthetic biology and targeted delivery systems—researchers can unlock the vast, untapped potential of natural products to yield the next generation of antimicrobial agents. Sustained investment, interdisciplinary collaboration, and policies that incentivize antibacterial development are critical to translating these scientific advances into therapies that protect our present and secure our future against the relentless threat of antimicrobial resistance [8] [32] [35].

The Modern Toolkit: AI, Omics, and Integrated Workflows for Accelerated Discovery

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Target and Lead Prediction

The discovery and development of new therapeutics from natural products (NPs) represent a cornerstone of modern pharmacology, with approximately 60% of medicines approved in the last three decades originating from NPs or their derivatives [36]. However, the traditional drug discovery paradigm faces formidable challenges characterized by lengthy development cycles, prohibitive costs, and high preclinical attrition rates [37]. The process from lead compound identification to regulatory approval typically spans over 12 years with cumulative expenditures exceeding $2.5 billion, while clinical trial success probabilities decline precipitously from Phase I (52%) to Phase II (28.9%), culminating in an overall success rate of merely 8.1% [37].

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have emerged as transformative technologies poised to address these inefficiencies by systematically decoding the complex relationships between natural product structures, their protein targets, and desired biological activities [37] [38]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of AI-driven methodologies specifically tailored for target identification and lead optimization within natural product drug discovery, framing these computational approaches within the broader context of natural product research principles.

AI and ML Fundamentals for Drug Discovery

Artificial intelligence develops systems capable of human-like reasoning and decision-making, with contemporary AI systems integrating both machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) to address pharmaceutical challenges ranging from target validation to formulation optimization [37]. ML employs algorithmic frameworks to analyze high-dimensional datasets, identify latent patterns, and construct predictive models through iterative optimization processes [37]. The field has evolved into four principal paradigms, each with distinct applications in natural product research:

- Supervised Learning: Utilizes labeled datasets for classification via algorithms like support vector machines (SVMs) and for regression via algorithms like support vector regression (SVR) and random forests (RFs) [37].

- Unsupervised Learning: Identifies latent data structures through clustering and dimensionality reduction techniques (such as principal component analysis and K-means clustering) to reveal underlying pharmacological patterns and streamline chemical descriptor analysis [37].

- Semi-Supervised Learning: Boosts drug-target interaction prediction by leveraging a small set of labeled data alongside a large pool of unlabeled data, enhancing prediction reliability through model collaboration and simulated data generation [37].

- Reinforcement Learning: Optimizes molecular design via Markov decision processes, where agents iteratively refine policies to generate inhibitors and balance pharmacokinetic properties through reward-driven strategies [37].

Table 1: Machine Learning Paradigms in Natural Product Drug Discovery

| ML Paradigm | Key Algorithms | Natural Product Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | SVMs, Random Forests, SVR | Target classification, activity prediction, ADMET property estimation | High accuracy with quality labeled data, clear evaluation metrics |

| Unsupervised Learning | PCA, K-means, t-SNE | Compound clustering, chemical space visualization, novelty detection | No labeled data required, reveals hidden patterns in NP libraries |

| Semi-Supervised Learning | Label propagation, self-training | Target prediction with limited bioactivity data | Leverages abundant unlabeled NP data, improves generalization |

| Reinforcement Learning | Q-learning, Policy gradients | De novo molecular design, multi-parameter optimization | Discovers novel NP-inspired scaffolds, balances multiple properties |

| 1-Ethyl-3-methyl-3-phospholene 1-oxide | 1-Ethyl-3-methyl-3-phospholene 1-oxide, CAS:7529-24-0, MF:C7H13OP, MW:144.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tribenuron-methyl | Tribenuron-methyl|CAS 101200-48-0|Research Compound | High-purity Tribenuron-methyl, a sulfonylurea ALS inhibitor herbicide for agricultural research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Deep learning, a subset of ML utilizing multi-layered neural networks, has demonstrated remarkable performance in deciphering intricate structure-activity relationships, facilitating de novo generation of bioactive compounds with optimized pharmacokinetic properties [37]. The efficacy of these algorithms is intrinsically linked to the quality and volume of training data, particularly in deciphering latent patterns within complex biological datasets [37].

AI-Driven Target Prediction for Natural Products

The Challenge of Natural Product Target Identification

Despite the significant number of NPs discovered, their interaction profiles with drug targets, primarily proteins, remain largely undefined [36]. Bioactivity data for natural products is often limited, creating a fundamental obstacle for predictive modeling [36] [39]. Furthermore, natural products exhibit distinct structural differences compared to synthetic molecules, including higher molecular weights, more complex scaffolds, and greater structural diversity, which complicates the application of conventional prediction tools trained primarily on synthetic compound libraries [39].

Similarity-Based Target Prediction Approaches

Similarity-based target prediction operates on the premise that structurally similar molecules tend to bind similar protein targets [36]. This approach represents a straightforward and efficient strategy for ligand-based target prediction due to its flexibility, low computational cost, and remarkable predictive performance [36]. The fundamental workflow involves:

- Reference Library Construction: Compounding compounds with standardized representations, precise target annotations, and significant biological activities.

- Similarity Calculation: Ranking reference compounds based on their structural similarity to query compounds using molecular fingerprints or descriptors.

- Target Assignment: Assigning targets associated with the top N most similar reference compounds to the query compound.

Table 2: Similarity-Based Target Prediction Techniques for Natural Products

| Technique | Methodology | Optimal Parameters | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top N Hits | Considers targets associated with top N compounds with highest similarities | Top 5 hits most effective [36] | Simple implementation, interpretable results | Increased false positives with larger N values |

| Mean Similarity | Ranks targets according to mean similarity scores of predefined similar compounds per target | Top 3 similar compounds [36] | Reduces bias from single compounds, more robust | Computationally more intensive |

| Statistical Significance | Transforms similarity scores into p-values or E-values | Varies by implementation | Provides statistical confidence measures | Complex implementation, may require specialized expertise |

Several specialized tools have been developed for similarity-based target prediction of natural products:

- CTAPred: An open-source command-line tool specifically designed for NP target prediction that applies fingerprinting and similarity-based search in a two-stage approach. It first generates a compound-target activity reference dataset from public data focusing on protein targets known or likely to interact with NPs, then identifies potential targets for query compounds based on similarity to this curated reference set [36].

- SEA (Similarity Ensemble Approach): Helps rationalize polypharmacology effects by relating targets based on the set-wise chemical similarity among their ligands [36].

- SwissTargetPrediction: Uses path-based fingerprints for 2D similarity and Manhattan distance between Electroshape 5D for 3D similarity [36].

- D3CARP: Provides flexibility allowing users to choose between three molecular fingerprints for 2D similarity and uses LS-align for 3D structural alignment [36].

Deep Learning with Transfer Learning for Natural Products

To address the limited bioactivity data for natural products, transfer learning has emerged as a powerful technique for building accurate target prediction models [39]. This approach involves:

- Pre-training: Training a deep learning model (such as a multilayer perceptron) on a large-scale bioactivity dataset (like ChEMBL) with natural products removed.

- Fine-tuning: Further training the pre-trained model on a limited natural product dataset with a higher learning rate and some parameters frozen, allowing the model to adapt to the specific distribution of natural products.