From Genes to Medicines: Unraveling the Biosynthesis and Biogenesis of Secondary Metabolites

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the biosynthesis and biogenesis of secondary metabolites, crucial compounds with vast pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

From Genes to Medicines: Unraveling the Biosynthesis and Biogenesis of Secondary Metabolites

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the biosynthesis and biogenesis of secondary metabolites, crucial compounds with vast pharmaceutical and industrial applications. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge with cutting-edge methodologies. The scope spans from the core biochemical pathways and ecological functions of secondary metabolites to advanced genome mining and multi-omics techniques for their discovery. It further addresses critical challenges in optimizing production and offers rigorous frameworks for validating and comparing biosynthetic gene clusters, serving as a strategic guide for accelerating natural product-based drug discovery.

The Chemical Language of Life: Fundamentals of Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis

Secondary metabolites are low-molecular-weight organic compounds produced by plants and microbes under specific conditions which, unlike primary metabolites, are not directly involved in the fundamental processes of growth, development, or reproduction [1]. These specialized compounds serve crucial ecological functions in defense, protection, and signaling for the organisms that produce them, while also providing immense value to humans as pharmaceuticals, chemical feedstocks, and cosmetic ingredients [1] [2] [3]. The complex biosynthetic pathways of many secondary metabolites remain only partially understood, presenting both a challenge and opportunity for research aimed at harnessing their full potential in therapeutic applications [4]. This review examines the core definitions, biosynthetic origins, and advanced research methodologies characterizing these compounds, framed within the context of contemporary biosynthesis and biogenesis research.

Defining Characteristics and Ecological Significance

Fundamental Distinctions from Primary Metabolism

Secondary metabolites diverge from primary metabolites in several key aspects. While primary metabolites such as amino acids, nucleotides, and carbohydrates are ubiquitous across all plant species and essential for basic cellular functions, secondary metabolites exhibit restricted taxonomic distribution, often being species-specific or produced only under particular environmental conditions [1]. Their production is typically temporally and spatially regulated, accumulating during specific developmental stages or in specialized tissues and organs [5]. From an evolutionary perspective, secondary metabolites represent adaptive traits that enhance an organism's survival and fitness in specific ecological contexts rather than supporting core physiological processes.

Major Classes and Chemical Diversity

The structural diversity of secondary metabolites can be categorized into several major classes based on their biosynthetic origins and chemical structures, each with distinct biological activities and ecological functions, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Major Classes of Plant Secondary Metabolites and Their Functions

| Class | Biosynthetic Origin | Representative Compounds | Ecological Functions | Human Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolics | Shikimate/Phenylpropanoid pathways | Flavonoids, Lignans, Tannins | UV protection, antioxidant, structural support | Antioxidants, nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory agents |

| Terpenoids | Mevalonic acid (MVA) or Methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways | Artemisinin, Taxol, Carotenoids | Defense against herbivores, attraction of pollinators | Antimalarials, anticancer drugs, fragrances |

| Alkaloids | Various amino acid precursors | Morphine, Quinine, Caffeine | Defense against herbivores and microbes | Analgesics, antimalarials, stimulants |

| Specialized Metabolites | Combined pathways | Acylphloroglucinolated catechins, Pilosanol-type molecules | Species-specific defense mechanisms | Potential pharmaceutical lead compounds [6] |

Ecological Roles and Defense Functions

Secondary metabolites constitute a sophisticated chemical defense arsenal that enables plants to interact with and adapt to their environment. They function as phytoprotectants against herbivores, pathogens, and competing plants through toxic, repellent, or antinutritive effects [1]. Additionally, they provide protection from abiotic stresses including UV radiation, extreme temperatures, and drought through antioxidant activity and reactive oxygen species scavenging [1]. Beyond defense, they facilitate ecological interactions such as attracting pollinators and seed dispersers through pigments and volatiles, and mediating symbiotic relationships with soil microorganisms [3].

Biosynthesis and Regulatory Mechanisms

Fundamental Biosynthetic Pathways

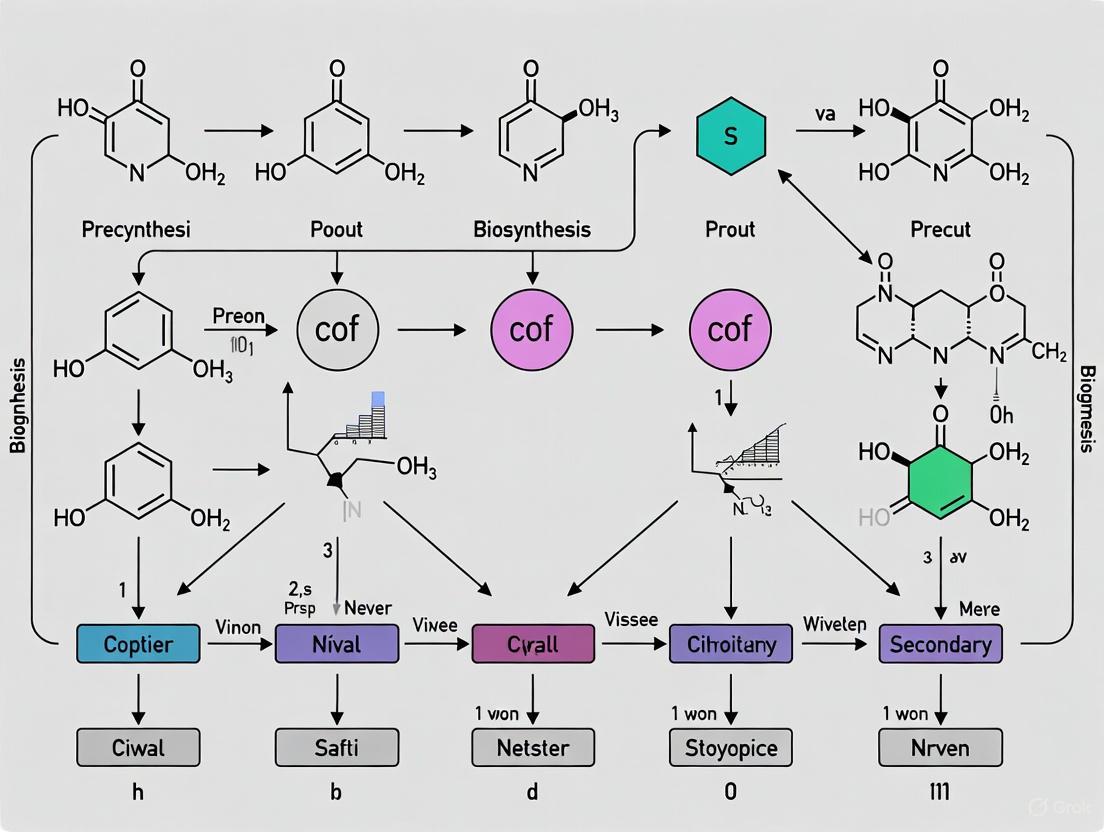

The production of secondary metabolites in plants originates from several primary metabolic pathways that provide the basic carbon skeletons and precursor molecules, as illustrated in Figure 1. The shikimic acid pathway converts simple carbohydrates into aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan) that serve as precursors for phenolic compounds, alkaloids, and indole derivatives. The malonic acid pathway, although less common in higher plants, produces polyketides through sequential condensation of acetyl-CoA units. The mevalonic acid (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways generate isoprenoid precursors (isopentenyl pyrophosphate and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate) for terpenoid biosynthesis, while various amino acid precursors form the backbone structures for alkaloid diversity.

Diagram Title: Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Pathways

Light-Mediated Regulation of Biosynthesis

Light serves as a key environmental factor regulating the synthesis of plant secondary metabolites through multidimensional mechanisms [1]. Different light qualities achieve differential biological regulation through specialized photoreceptor systems, with UV radiation activating the UVR8 photoreceptor pathway to enhance phenolic and flavonoid production, blue light influencing phenylpropanoid metabolism through cryptochrome-mediated networks, and red light modulating terpenoid production via phytochrome-mediated hormonal signaling [1]. The molecular mechanisms of UV light regulation are detailed in Figure 2.

Diagram Title: UV Light Regulation of Secondary Metabolism

Light intensity dynamically modulates secondary metabolite accumulation by affecting photosynthetic efficiency and energy allocation, while photoperiod coordinates metabolic rhythms through circadian clock genes [1]. These light-responsive mechanisms constitute a chemical defense strategy that enables plants to adapt to their environment while providing critical targets for directed regulation of medicinal components and functional nutrients.

Advanced Research Methodologies

Analytical Approaches for Metabolite Identification

Modern research on secondary metabolites employs sophisticated analytical technologies for compound discovery and characterization. Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) has emerged as a powerful platform, with high-resolution MS (HRMS) analyzers such as quadrupole time-of-flight (qTOF) and orbitrap providing enhanced m/z resolution, dynamic range, and sensitivity for structural elucidation [6]. Figure 3 illustrates a representative workflow for LC/MS data processing to identify novel secondary metabolites.

Diagram Title: LC/MS Metabolite Discovery Workflow

Protocols for processing LC/MS data include multiple critical steps to extract meaningful information from complex natural product extracts. Raw MS spectra undergo noise filtering to remove unwanted signals, followed by deisotoping to simplify spectral interpretation [6]. Processed MS spectra are then clustered based on similarity scoring between consecutive scans to generate Representative MS Spectra (RMS) corresponding to single metabolites [6]. These RMS are subsequently used for dereplication studies to identify known compounds and highlight novel metabolites of interest, with approaches such as the Fresh Compound Index (FCI) scoring system evaluating structural novelty against in-house databases [6].

Statistical Experimental Design for Optimization

Statistical experimental designs (Design of Experiments, DoE) provide powerful approaches for optimizing secondary metabolite production in plant cell suspension cultures (PCSCs), overcoming limitations of traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) methodologies [2]. These approaches enable researchers to systematically investigate the effects of multiple factors and their interactions on metabolite yield in a cost-efficient manner, significantly enhancing the productivity of plant cell cultures for pharmaceutical, chemical feedstock, and cosmetic applications [2]. Factorial designs allow simultaneous examination of multiple factors such as nutrient composition, hormone levels, and elicitor concentrations, reducing the total number of experiments required while providing comprehensive information about factor interactions [2].

Systems and Synthetic Biology Approaches

Advanced systems and synthetic biology tools are revolutionizing the characterization and engineering of plant metabolic pathways, as summarized in Table 2. These methodologies enable researchers to unravel complex biosynthetic networks and enhance the production of valuable natural products through directed genetic manipulation [4].

Table 2: Advanced Research Methods for Secondary Metabolite Pathway Analysis

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systems Biology | Co-expression analysis, Gene cluster identification, Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) | Identification of candidate genes in biosynthetic pathways, Elucidation of regulatory networks | Unbiased discovery of pathway components, Identification of natural genetic variants |

| Metabolite Profiling | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR-based metabolomics | Comprehensive chemical phenotyping, Tracking metabolic flux | Simultaneous analysis of numerous metabolites, Quantitative assessment of pathway activity |

| Computational Approaches | Deep learning algorithms, In silico fragmentation prediction, Database mining | Novel compound prediction, Spectral interpretation, Dereplication | Accelerated identification process, Prediction of previously uncharacterized metabolites |

| Protein Complex Analysis | Metabolon engineering, Protein-protein interaction studies | Optimization of metabolic channeling, Enhancement of pathway efficiency | Recreation of efficient biosynthetic complexes, Increased metabolic flux to target compounds |

Future directions in metabolic engineering include metabolon engineering to optimize metabolic channeling, artificial intelligence integration for pathway prediction and optimization, and development of sustainable production strategies underscoring the potential for cheaper and greener production of plant natural products [4].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Principle: Exposure to ultraviolet radiation, particularly UV-B (280-315 nm), activates plant defense mechanisms leading to increased biosynthesis of protective secondary metabolites including flavonoids, phenolics, and terpenoids [1].

Protocol:

- Plant Material Preparation: Utilize uniform, healthy plants or in vitro cultures at consistent developmental stages (e.g., 4-6 week old Arabidopsis plants or established cell suspension cultures).

- UV Treatment Setup: Position UV-B lamps (e.g., fluorescent UV-B tubes emitting at 312 nm) at appropriate distance to achieve desired fluence rate (typically 0.5-5 W mâ»Â²), measured with a UV radiometer.

- Elicitation Procedure: Expose plant material to UV-B radiation for controlled duration (e.g., 15 minutes to 4 hours depending on species sensitivity). For enhanced effect, follow UV treatment with dark incubation period (e.g., 36 hours) to facilitate metabolite accumulation [1].

- Harvest and Analysis: Collect plant material immediately or at designated time points post-elicitation. Flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until metabolite extraction and analysis.

Key Considerations: Include appropriate controls (non-UV exposed plants), monitor for potential UV stress damage, and optimize exposure duration and intensity for specific plant species [1].

LC/MS-Based Metabolite Discovery from Natural Products

Principle: High-resolution mass spectrometry coupled with liquid chromatography enables comprehensive profiling of secondary metabolites in complex plant extracts, facilitating discovery of novel compounds [6].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize plant tissue (e.g., 100 mg fresh weight) in extraction solvent (e.g., 80% methanol, 1 mL). Sonicate for 15 minutes and centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes. Collect supernatant for analysis.

- LC Conditions: Utilize reversed-phase chromatography (e.g., C18 column, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm) with mobile phase A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid). Apply gradient elution (e.g., 5-95% B over 20 minutes) at flow rate of 0.3 mL/min.

- MS Analysis: Operate high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF or Orbitrap) in data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode with electrospray ionization in both positive and negative modes. Set mass range to m/z 100-1500 with resolution >30,000.

- Data Processing:

- Noise Filtering: Remove ion peaks with intensity below predetermined threshold (e.g., <1000 counts) and m/z values below 100 [6].

- Deisotoping: Eliminate isotopic peaks to simplify spectra using algorithm-based approaches.

- Spectral Clustering: Group consecutive MS spectra with similarity scores above threshold (e.g., 0.90-0.95) using modified dot-product method to generate Representative MS Spectra (RMS) [6].

- Deconvolution: Apply filters to separate co-eluted metabolites when consecutive spectra show different base peak ions or convex downward patterns.

- Dereplication and Novelty Assessment: Compare RMS against in-house or public databases. Calculate Fresh Compound Index (FCI) to grade structural novelty [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Secondary Metabolite Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Supplies | C18 reversed-phase columns, HILIC columns, Solid-phase extraction cartridges | Metabolite separation, sample clean-up | Column chemistry selection critical for compound classes; SPE enables fractionation |

| Mass Spectrometry Reagents | Formic acid, Ammonium acetate, Acetonitrile (LC-MS grade), Methanol (LC-MS grade) | Mobile phase modifiers, solvent systems | High-purity reagents essential for sensitive MS detection; acid modifiers improve ionization |

| Plant Culture Materials | Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium, Phytohormones (auxins, cytokinins), Elicitors (methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid) | Plant tissue culture, metabolite induction | Hormone balance critical for cell growth vs. production; elicitors enhance defense compounds |

| Molecular Biology Tools | RNA isolation kits, cDNA synthesis kits, qPCR reagents, Gateway cloning systems | Gene expression analysis, pathway engineering | Quality RNA essential for transcriptomics; modular cloning enables pathway assembly |

| Chemical Standards | Authentic standards (e.g., rutin, quercetin, artemisinin), Stable isotope-labeled internal standards | Metabolite identification and quantification | Necessary for definitive compound identification; isotope standards enable precise quantification |

| Specialized Light Sources | UV-B lamps (312 nm), LED arrays with specific wavelengths, Photoperiod-controlled growth chambers | Light quality studies, photoregulation research | Precise wavelength control essential for photoreceptor studies; intensity must be calibrated |

Secondary metabolites represent a vast reservoir of chemical diversity with profound ecological significance and substantial application potential in medicine and biotechnology. Their definition as compounds "beyond primary needs" underscores their specialized roles in environmental adaptation and defense rather than core physiological functions. Advanced research methodologies spanning analytical chemistry, statistical design, and molecular biology are rapidly accelerating our understanding of their complex biosynthetic pathways and regulatory mechanisms. The integration of systems and synthetic biology approaches, coupled with sophisticated analytical platforms, promises to unlock previously inaccessible chemical diversity, enabling sustainable production of valuable plant natural products for pharmaceutical and industrial applications. As research in this field continues to evolve, the fundamental definition of secondary metabolites as strategic chemical solutions to ecological challenges provides a robust framework for future discovery and innovation.

Secondary metabolites are low-molecular-weight organic compounds produced by plants and microorganisms under specific conditions. While not directly involved in fundamental growth and developmental processes, they play crucial roles in plant defense, protection, and regulation, while also serving as critical resources in pharmaceutical and industrial applications [1]. The biosynthesis of these compounds proceeds through several conserved metabolic pathways, with the shikimic acid, acetate-mevalonate, and acetate-malonate pathways representing three fundamental routes for aromatic compounds, terpenoids, and fatty acids/polyketides, respectively [7] [8] [9]. Understanding these pathways at a mechanistic level provides researchers with the foundational knowledge necessary to manipulate metabolic fluxes for enhanced production of valuable compounds through metabolic engineering and synthetic biology approaches [10]. This technical guide examines the enzymatic steps, regulation, and experimental methodologies for these core biosynthetic pathways within the context of secondary metabolite research.

Pathway Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

Shikimic Acid Pathway

The shikimate pathway is a seven-step metabolic pathway used by bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae, some protozoans, and plants for the biosynthesis of folates and aromatic amino acids (tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine). This pathway is not found in mammals, making it an attractive target for antimicrobial and herbicide development [7]. The pathway begins with the substrates phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP) and erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P), which undergo condensation catalyzed by DAHP synthase to form 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate (DAHP). Through a series of enzymatic transformations, this compound is ultimately converted to chorismate, a key branch point metabolite that serves as the precursor for the three aromatic amino acids and multiple secondary metabolites [7] [10].

The shikimate pathway represents the primary route for the biosynthesis of aromatic compounds in nature, with its intermediate shikimic acid serving as the key raw material for synthesis of the influenza antiviral drug oseltamivir (Tamiflu) [10]. Other important pharmaceutical intermediates produced via this pathway and its branches include quinic acid, gallic acid, pyrogallol, and catechol. Modern pharmacological studies have revealed that shikimic acid derivatives exhibit anti-tumor, anti-thrombosis, anti-inflammatory, anti-virus, and analgesic properties [10].

Acetate-Mevalonate Pathway

The mevalonate pathway, also known as the isoprenoid pathway or HMG-CoA reductase pathway, is an essential metabolic pathway present in eukaryotes, archaea, and some bacteria [8]. This pathway begins with acetyl-CoA and proceeds through a series of condensation and reduction steps to produce the five-carbon building blocks isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). These isoprenoid precursors are used to synthesize a diverse class of over 30,000 biomolecules including cholesterol, vitamin K, coenzyme Q10, and all steroid hormones [8].

The mevalonate pathway is best known as the target of statins, a class of cholesterol-lowering drugs that inhibit HMG-CoA reductase. The pathway is regulated through multiple mechanisms including transcriptional control by SREBP proteins, translational regulation, and enzyme phosphorylation [8]. Plants and most bacteria possess an alternative pathway for isoprenoid synthesis called the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) or non-mevalonate pathway, which produces the same IPP and DMAPP outputs through entirely different enzymatic reactions [8].

Acetate-Malonate Pathway

The acetate-malonate pathway includes the synthesis of fatty acids and aromatic compounds with the help of secondary metabolites [9]. The main precursors of this pathway are acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA, with the end products being saturated or unsaturated fatty acids or polyketides. Polyketides are secondary metabolites which further synthesize aromatic compounds through the polyketide pathway and represent an important class of therapeutic compounds including antibiotics, antifungals, and immunosuppressants [9].

In plants, the acetate-malonate pathway operates at the interface of central and lipid metabolism while also supporting the phenylpropanoid pathway of flavonoid biosynthesis [11]. The pathway provides malonyl-CoA moieties for the C2 elongation reaction catalyzed by chalcone synthase, which combines with phenylpropanoid pathway products to form the basic flavonoid backbone structure. Research in Arabidopsis thaliana has demonstrated that this pathway is transcriptionally coregulated with flavonoid biosynthetic genes and is essential for normal flavonoid accumulation [11].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Biosynthetic Pathways

| Feature | Shikimic Acid Pathway | Acetate-Mevalonate Pathway | Acetate-Malonate Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids and phenolic compounds | Production of isoprenoid precursors | Synthesis of fatty acids and polyketides |

| Initial Substrates | Phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP) and erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P) | Acetyl-CoA | Acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA |

| Key Intermediate | Shikimic acid | Mevalonic acid | Malonyl-CoA |

| End Products | Phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, folates, plant phenolics | IPP, DMAPP, sterols, carotenoids, terpenes | Fatty acids, flavonoids, polyketides |

| Organism Distribution | Bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae, plants, some protozoans | Eukaryotes, archaea, some bacteria | Universal |

| Pharmaceutical Significance | Tamiflu precursor, antibacterial targets | Statin targets, steroid hormones | Antibiotics, flavonoids with health benefits |

| Key Regulatory Enzymes | DAHP synthase, shikimate kinase | HMG-CoA reductase | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

Table 2: Key Enzymes and Their Functions in Biosynthetic Pathways

| Pathway | Enzyme | Reaction Catalyzed | Regulatory Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shikimic Acid | DAHP synthase | Condenses PEP and E4P to form DAHP | Feedback inhibited by aromatic amino acids |

| Shikimate dehydrogenase | Reduces 3-dehydroshikimate to shikimate | Constitutively expressed in E. coli | |

| EPSP synthase | Couples shikimate-3-phosphate with PEP to form EPSP | Inhibited by glyphosate herbicide | |

| Acetate-Mevalonate | HMG-CoA synthase | Condenses acetoacetyl-CoA with acetyl-CoA to form HMG-CoA | Transcriptional regulation by SREBP |

| HMG-CoA reductase | Reduces HMG-CoA to mevalonate | Rate-limiting step; statin target | |

| Mevalonate-5-kinase | Phosphorylates mevalonate to mevalonate-5-phosphate | Consumes ATP | |

| Acetate-Malonate | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | Carboxylates acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA | Postulated to be essential for flavonoid biosynthesis |

| Ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (KAT5) | Converts lipids to acetyl-CoA in peroxisomes | Coexpressed with flavonoid genes | |

| Chalcone synthase | Combines p-coumaroyl-CoA with malonyl-CoA for C2 elongation | Key entry point to flavonoid biosynthesis |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Metabolic Engineering of the Shikimate Pathway

Background: Metabolic engineering of the shikimate pathway has significantly improved the yield of shikimic acid and its derivatives. Escherichia coli serves as the most commonly used bacterium in the metabolic engineering of this pathway and its branches due to its well-characterized genetics and metabolism [10].

Protocol for Enhanced Shikimic Acid Production:

Strain Construction: Begin with an appropriate E. coli host strain (e.g., K-12 derivatives). Genetically modify the strain to overexpress key shikimate pathway genes including aroG (encoding DAHP synthase feedback-resistant to phenylalanine inhibition), aroB (encoding DHQ synthase), and aroE (encoding shikimate dehydrogenase) [10].

Branch Pathway Disruption: Knock out genes encoding shikimate kinase (aroL and aroK) to prevent conversion of shikimic acid to shikimate-3-phosphate, thereby accumulating shikimic acid. Additionally, disrupt the shiA gene encoding shikimate transporters to prevent shikimic acid uptake from the extracellular environment [10].

Precursor Supply Enhancement: Modify central carbon metabolism to increase availability of the precursors phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP) and erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P). This can be achieved by overexpressing transketolase (tktA) to enhance E4P supply and employing PEP synthase (ppsA) overexpression or eliminating PEP-dependent phosphotransferase system (PTS) sugar transport to increase PEP availability [10].

Fermentation Conditions: Cultivate engineered strains in defined mineral media with glucose as the carbon source. Maintain temperature at 30-37°C with appropriate aeration. Monitor shikimic acid accumulation throughout the fermentation process [10].

Product Analysis: Quantify shikimic acid production using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection or LC-MS/MS for precise quantification [10].

Investigating the Acetate Pathway for Flavonoid Biosynthesis

Background: The acetate pathway, also known as the polyketide pathway, provides malonyl-CoA for flavonoid biosynthesis. This pathway operates at the interface of central and lipid metabolism and supports the phenylpropanoid pathway [11].

Protocol for Assessing Acetate Pathway Mutants:

Mutant Selection: Identify or generate mutant lines for key acetate pathway enzymes using T-DNA insertion mutants or artificial microRNA (amiRNA) strategies. Key targets include ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (KAT5), enoyl-CoA hydratase (ECH), 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (HCD), and cytosolic acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) [11].

Metabolite Profiling: Employ a hierarchical metabolomics approach covering primary metabolites, secondary metabolites, and lipids. For primary metabolites, use GC-MS analysis of polar extracts. For secondary metabolites (flavonoids), utilize LC-MS/MS with multiple reaction monitoring for specific flavonoid compounds [11].

Lipid Analysis: Extract lipids using appropriate organic solvents (e.g., chloroform:methanol mixtures) and analyze using LC-MS with electrospray ionization for comprehensive lipid profiling [11].

Gene Expression Analysis: IsRNA from plant tissues and perform quantitative RT-PCR to measure expression levels of key structural genes of the flavonoid pathway (e.g., CHS, CHI, F3H) and acetate pathway genes [11].

Data Integration: Correlate metabolic phenotypes with gene expression patterns to establish the role of specific acetate pathway enzymes in flavonoid biosynthesis and lipid metabolism [11].

Light-Mediated Regulation of Secondary Metabolite Pathways

Background: Light serves as a key environmental factor regulating the synthesis of plant secondary metabolites through multidimensional regulatory mechanisms. Different light qualities activate or suppress specific metabolic pathways via signal transduction networks mediated by specialized photoreceptors [1].

Protocol for Light Quality Experiments:

Light Treatment Setup: Establish controlled environment growth chambers with specific light quality treatments using LED systems. Key treatments include:

- UV-B light (280-315 nm) for activating phenolic and flavonoid biosynthesis

- Blue light (450-495 nm) mediated by cryptochrome and phototropin receptors

- Red light (620-750 nm) acting through phytochrome receptors [1]

Plant Material and Growth Conditions: Use uniform plant materials (e.g., seedlings or tissue cultures) of species known for secondary metabolite production (e.g., Artemisia argyi, Taxus wallichiana). Maintain consistent light intensity and photoperiod across treatments except for the quality being tested [1].

Sample Collection and Extraction: Harvest plant tissues at multiple time points following light exposure. Immediately freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C. Extract metabolites using appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol for phenolics, hexane for terpenoids) [1].

Transcriptional Analysis: Isolate RNA from light-treated tissues and perform RNA-seq or qRT-PCR to monitor expression of pathway genes and transcription factors. Key targets include HY5, MYB transcription factors, and structural genes of relevant pathways [1].

Metabolite Quantification: Analyze specific secondary metabolites using HPLC, GC-MS, or LC-MS/MS. For shikimate pathway-related compounds, focus on phenylpropanoids and flavonoids. For mevalonate pathway, analyze terpenoid profiles [1].

Pathway Visualization and Regulation

Shikimic Acid Pathway Engineering Strategy

Diagram 1: Shikimic acid pathway with engineering targets. Key engineering strategies include overexpression of DAHP synthase (AroG/F/H) and knockout of shikimate kinase (AroL/K) to accumulate shikimic acid.

Mevalonate Pathway Regulation

Diagram 2: Mevalonate pathway regulation. The rate-limiting HMG-CoA reductase step is targeted by statins, with transcriptional regulation by SREBP. Some organisms utilize an alternative MEP pathway.

Acetate-Malonate Pathway in Flavonoid Biosynthesis

Diagram 3: Acetate-malonate pathway in flavonoid biosynthesis. The pathway provides malonyl-CoA for chalcone synthase, which combines with phenylpropanoid pathway products to form flavonoid precursors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosynthetic Pathway Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Enzymes | DAHP synthase (AroG/F/H), HMG-CoA reductase, Chalcone synthase (CHS) | Pathway catalysis and regulation studies | Protein purification, enzyme kinetics, inhibitor screening |

| Inhibitors | Glyphosate (EPSP synthase inhibitor), Statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) | Pathway perturbation studies | Mechanism of action studies, flux control analysis |

| Analytical Standards | Shikimic acid, mevalonolactone, malonyl-CoA, naringenin | Metabolite quantification and method validation | HPLC, LC-MS/MS calibration, absolute quantification |

| Expression Vectors | pET system for E. coli, plant binary vectors | Heterologous gene expression | Pathway engineering, enzyme characterization |

| Antibodies | Anti-HMGCR, anti-ACC, anti-MYB transcription factors | Protein detection and quantification | Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, localization studies |

| Mutant Collections | Arabidopsis T-DNA lines, E. coli knockout collections | Gene function analysis | Phenotypic screening, metabolomic profiling |

| Light Sources | UV-B lamps, specific wavelength LED systems | Photoregulation studies | Light quality experiments, photoreceptor studies |

| Oxaziclomefone | Oxaziclomefone|Herbicide for Research Use | Oxaziclomefone is a selective herbicide that inhibits cell expansion in grasses. This product is for laboratory research use only (RUO) and is not intended for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Methyl Orsellinate | Methyl 2,4-Dihydroxy-6-methylbenzoate|Methyl Orsellinate | Methyl 2,4-dihydroxy-6-methylbenzoate (Methyl Orsellinate) is a lichen metabolite for cancer, antifungal, and inflammation research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The shikimic acid, acetate-mevalonate, and acetate-malonate pathways represent fundamental biosynthetic routes that interface between primary metabolism and specialized secondary metabolite production. Each pathway possesses distinct regulatory mechanisms, enzymatic components, and biotechnological applications. Contemporary research employs sophisticated metabolic engineering strategies, comprehensive metabolomic profiling, and light-mediated regulation to manipulate these pathways for enhanced production of valuable compounds. The continued elucidation of regulatory networks and rate-limiting steps across these interconnected pathways will further advance our ability to engineer microbial and plant systems for pharmaceutical and industrial applications, particularly through the integration of synthetic biology approaches with traditional metabolic engineering.

Secondary metabolites (SMs) represent a vast reservoir of structurally complex molecules with profound impacts on human health, agriculture, and ecology. These compounds are synthesized by bacteria, fungi, and plants through specialized metabolic pathways. Biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) encode the enzymatic machinery for SM production, typically featuring core synth(et)ase genes surrounded by accessory tailoring enzymes, regulators, and transporters [12]. Among these core enzymes, polyketide synthases (PKSs), nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), and terpene cyclases (TCs) serve as the fundamental architects of chemical diversity, generating an astonishing array of molecular scaffolds from simple building blocks [13] [14]. These enzymatic systems provide the foundational carbon frameworks that tailoring enzymes subsequently modify, yielding the structural complexity characteristic of natural products.

The engineering of these enzymatic pathways through combinatorial biosynthesis has emerged as a powerful strategy for generating novel compounds with enhanced or new biological activities [14]. This technical guide examines the core machinery of PKS, NRPS, and terpene cyclase enzymes, detailing their mechanisms, experimental characterization, and engineering approaches, framed within the context of contemporary secondary metabolite research.

Polyketide Synthases (PKS): Molecular Assembly Lines

Architectural Domains and Classification

Polyketide synthases are multifunctional enzymes that assemble polyketide backbones through sequential decarboxylative Claisen condensations of acyl-CoA precursors, analogous to fatty acid synthesis but with far greater product diversity [13]. Fungal PKSs are typically iterative type I enzymes that carry multiple catalytic domains on a single polypeptide and reuse their active sites for multiple catalytic cycles [15]. These mega-enzymes are classified into three major categories based on their domain composition and reduction level:

- Non-reducing PKS (NR-PKS): Contain starter unit acyl carrier protein transacylase (SAT), ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), product template (PT), acyl carrier protein (ACP), and thioesterase (TE) domains. They produce unreduced, aromatic polyketides [15] [14].

- Partially-reducing PKS (PR-PKS): Lack full reductive capacity but may contain ketoreductase (KR) domains [14].

- Highly-reducing PKS (HR-PKS): Contain KS, AT, ACP, and multiple reductive domains (KR, dehydratase (DH), enoyl reductase (ER)) that generate highly reduced, often chiral, polyketide chains [15] [14].

Table 1: Core Domains in Fungal Polyketide Synthases

| Domain | Function | Present in PKS Type |

|---|---|---|

| SAT (Starter unit ACP transacylase) | Selects and loads starter unit | NR-PKS |

| KS (Ketosynthase) | Catalyzes chain elongation | All types |

| AT (Acyltransferase) | Selects and loads extender unit | All types |

| ACP (Acyl Carrier Protein) | Carries growing polyketide chain | All types |

| PT (Product Template) | Controls polyketide cyclization | NR-PKS |

| KR (Ketoreductase) | Reduces ketone to alcohol | HR-PKS, PR-PKS |

| DH (Dehydratase) | Eliminates water to form alkene | HR-PKS |

| ER (Enoylreductase) | Reduces alkene to alkane | HR-PKS |

| TE (Thioesterase) | Releases final product | NR-PKS, some HR-PKS |

Representative Biosynthetic Pathways and Engineering

The collaboration between different PKS types enables the synthesis of complex benzenediol lactones. For example, the phytotoxin aldaulactone from Alternaria dauci is synthesized by the collaborative action of a highly-reducing PKS (HR-PKS) and a non-reducing PKS (NR-PKS) [15]. The HR-PKS (AdPKS7) synthesizes a reduced polyketide that is transferred to the NR-PKS (AdPKS8), which performs additional elongations and cyclizations to form the benzenediol lactone scaffold [15].

Engineering PKS enzymes through domain swapping has proven effective for generating novel compounds. Swapping the product template (PT) domain from ApdA (in asperthecin biosynthesis) into PKS4 (in bikaverin biosynthesis) resulted in the production of a novel α-pyranoanthraquinone [14]. Similarly, swapping both PT and TE domains between different NR-PKS systems has yielded novel macrocyclic compounds, including the unexpected polyketide 1-(7,9,10-trihydroxy-1-oxo-1H-benzo[g]isochromen-3-yl)pentane-2,4-dione [14].

Figure 1: PKS Classification and Engineering Workflow. Fungal polyketide synthases are categorized based on their reductive capabilities and domain architecture, with engineering strategies enabling diversification of polyketide products.

Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS): Template-Independent Peptide Assembly

Modular Organization and Mechanism

Nonribosomal peptide synthetases are multimodular enzymatic assembly lines that synthesize structurally diverse peptides without direct mRNA templating. Each NRPS module is responsible for incorporating one amino acid building block into the growing peptide chain, with the number and order of modules determining the final peptide sequence [15]. The core domains within each NRPS module include:

- Adenylation (A) domain: Selects and activates the specific amino acid substrate through adenylation.

- Peptidyl Carrier Protein (PCP) domain: Shuttles the activated amino acid as a thioester using a phosphopantetheine prosthetic group.

- Condensation (C) domain: Catalyzes peptide bond formation between adjacent modules.

Additional specialized domains include epimerization (E) domains that convert L-amino acids to D-configurations, methyltransferase (MT) domains that install N-methyl groups, and various termination domains (thioesterase TE or reductase R) that release the final product [15] [14].

Hybrid NRPS Systems and Unconventional Mechanisms

Many natural products arise from hybrid NRPS systems that incorporate polyketide and terpenoid elements. The flavunoidine pathway from Aspergillus flavus exemplifies collaboration between NRPS and terpene cyclases, where a single-module NRPS (FlvI) esterifies 5,5-dimethyl-L-pipecolate to an oxygenated sesquiterpene core [16]. This hybrid TC/NRPS cluster produces alkaloidal terpenoids with cage-like tetracyclic structures previously unknown in nature [16].

Unconventional NRPS mechanisms continue to be discovered. In Mortierella alpina, NRPS enzymes with atypical epimerase/condensation domains produce cyclic peptides like malpinin acetylated hexapeptides and malpibaldin cyclic pentapeptides [17]. These systems highlight the evolutionary diversity of NRPS machinery across fungal lineages.

Table 2: Experimental Characterization of NRPS Selectivity

| A-domain Specificity | Representative Amino Acid | Non-Proteinogenic Examples | Product Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aliphatic | L-Valine, L-Leucine | D-forms, N-methylated | Cyclosporine A |

| Aromatic | L-Tryptophan, L-Phenylalanine | Hydroxylated, chlorinated | Echinocandin |

| Acidic | L-Glutamate, L-Aspartate | Adenylate-forming reductases | β-lactam antibiotics |

| Unusual | L-Ornithine, L-Pipecolate | Dimethylcadaverine | Flavunoidine [16] |

Terpene Cyclases: Architectural Masters of Molecular Complexity

Cyclization Mechanisms and Structural Diversity

Terpene cyclases transform linear, achiral polyprenyl pyrophosphates into an immense variety of carbocyclic skeletons with exquisite stereochemical control. Using farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP, C15) or geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP, C20) as substrates, these enzymes generate mono-, sesqui-, and diterpenes through carbocation-mediated cyclization cascades [13] [17]. The catalytic mechanism involves substrate ionization to generate reactive carbocation intermediates that undergo precise cyclization, rearrangement, and termination steps, all controlled within the enzyme's active site.

The flavunoidine biosynthetic pathway demonstrates sophisticated terpene cyclase collaboration. In Aspergillus flavus, two distinct terpene cyclases work sequentially: FlvE produces (+)-acoradiene, a sesquiterpene hydrocarbon, which is then remodeled by a second TC (FlvF) and cytochrome P450 oxygenases to generate a tetracyclic, cage-like core structure [16]. This exemplifies how terpene cyclases can generate unprecedented molecular architectures.

Distribution Across Fungal Lineages

Terpenoid biosynthesis dominates the secondary metabolite landscape across diverse fungal lineages. Genomic analyses reveal that terpene clusters represent the most abundant class of predicted BGCs in early-diverging Mucoromycotina, with diverse domain compositions suggesting highly variable products [17] [18]. In the Hypoxylaceae family, terpene cyclases contribute significantly to the remarkable chemical diversity observed, with species-specific BGCs generating unique terpenoid scaffolds [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Genome Mining and Cluster Identification

The systematic identification of biosynthetic gene clusters employs integrated bioinformatics pipelines:

Genome Sequencing and Assembly: Obtain high-quality genome sequences using long-read technologies (e.g., Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) to achieve contiguity (N50 > 1 Mbp preferred) sufficient for complete cluster capture [12].

Gene Prediction and Annotation: Employ tools like GLIMMERHMM for ab initio gene prediction, complemented by transcriptomic evidence for accurate exon-intron boundary definition [17].

BGC Identification: Utilize antiSMASH with ClusterFinder extension to predict BGC boundaries and classify cluster types based on core biosynthetic genes [19] [17].

Comparative Analysis: Process predicted BGCs with BiG-SCAPE to organize into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) based on content and architecture, revealing evolutionary relationships [19] [12].

Heterologous Expression: Clone entire BGCs into fungal expression hosts (e.g., Aspergillus nidulans) to confirm cluster functionality and characterize metabolic output [16].

Pathway Elucidation through Gene Inactivation

Systematic dissection of individual gene functions follows this workflow:

Targeted Gene Knockout: Replace target genes with selectable markers using homologous recombination or CRISPR/Cas9 systems [16].

Metabolite Profiling: Compare metabolic profiles of wild-type and knockout strains using LC-HRMS and MS/MS molecular networking to identify missing compounds [16].

Intermediate Isolation: Purify and structurally characterize pathway intermediates that accumulate in knockout mutants [16].

Enzyme Reconstitution: Heterologously express and purify individual enzymes for in vitro biochemical characterization using appropriate substrates [16].

Feeding Experiments: Supplement knockout strains with putative intermediates to establish precursor-product relationships and pathway sequence [16].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for BGC Characterization. Integrated approaches combining bioinformatics, genetics, and metabolomics enable comprehensive dissection of secondary metabolic pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for PKS, NRPS, and Terpene Cyclase Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | BGC identification and annotation | Predicts cluster types and boundaries based on core biosynthetic genes [19] [17] |

| BiG-SCAPE | Comparative analysis of BGCs | Groups BGCs into Gene Cluster Families based on similarity [12] |

| Heterologous Host Systems | Cluster expression and validation | Aspergillus nidulans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae for pathway reconstitution [16] |

| LC-HRMS/MS | Metabolite profiling and identification | Structural characterization of natural products and intermediates [16] [19] |

| Gene Knockout Tools | CRISPR/Cas9, homologous recombination | Functional characterization of individual cluster genes [16] |

| In vitro Enzyme Assays | Biochemical characterization | Substrate specificity and kinetic analysis of purified enzymes [16] |

| MIBIG Database | Repository of known BGCs | Reference for comparative analysis of novel clusters [17] |

| Allyl methyl sulfide | Allyl methyl sulfide, CAS:10152-76-8, MF:C4H8S, MW:88.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Picolinafen | Picolinafen, CAS:137641-05-5, MF:C19H12F4N2O2, MW:376.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The enzymatic machinery of PKS, NRPS, and terpene cyclases represents nature's sophisticated toolkit for generating chemical diversity. These core biosynthetic systems employ distinct yet complementary strategies to construct complex molecular scaffolds from simple building blocks. Combinatorial biosynthesis approaches that engineer these systems through domain swapping, module fusion, and pathway recombination are rapidly advancing our ability to access novel chemical space [14].

Future research directions will focus on elucidating the structural basis of enzyme specificity and mechanism, unlocking the vast majority of orphan BGCs with unknown products, and developing increasingly precise genome editing tools for pathway engineering [12] [14]. As genomic and metabolomic technologies continue to advance, our understanding of these remarkable enzymatic systems will deepen, accelerating the discovery and engineering of valuable natural products for therapeutic and industrial applications.

Secondary metabolites (SMs) represent a vast array of plant-synthesized compounds that, while not essential for primary growth and development, are indispensable for survival and ecological interactions [20]. These compounds provide plants, as sessile organisms, with a chemical toolkit to defend against biotic and abiotic stresses, facilitate communication, and adapt to environmental challenges [21] [22]. The biosynthesis of these metabolites is tightly regulated through sophisticated pathways and is often induced or enhanced under stress conditions, enabling plants to tolerate stressful environments [20]. Understanding the ecological roles of SMs is crucial for fundamental plant science and has significant implications for developing stress-resistant crops and discovering novel pharmaceutical compounds [20] [23]. This review provides an in-depth analysis of the defense, signaling, and adaptive functions of secondary metabolites, framed within the context of their biosynthesis and biogenesis.

Classes of Secondary Metabolites and Their Defense Functions

Secondary metabolites are broadly classified into several major categories based on their chemical structures and biosynthetic origins. Each class encompasses a diverse array of compounds with specific ecological roles, particularly in plant defense.

Table 1: Major Classes of Secondary Metabolites and Their Defense Roles

| Metabolite Class | Biosynthetic Pathway | Key Subclasses | Primary Ecological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids/Terpenes [21] [22] | Mevalonic Acid (MVA) & Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) pathways [21] | Monoterpenes (C10), Sesquiterpenes (C15), Diterpenes (C20), Triterpenes (C30) [21] | Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities; herbivore deterrence; membrane stabilization; thermal stress tolerance [21] [22] |

| Phenolics [21] [22] | Shikimic Acid pathway [22] | Phenolic acids, Flavonoids, Lignin, Tannins, Coumarins [22] | Structural defense (lignin, suberin); potent antioxidant activity; neutralization of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) [21] [22] |

| Alkaloids [20] [21] | Derived from amino acids | Indole alkaloids, tropane alkaloids, etc. [20] | Toxicity to herbivores and pathogens; acting as natural pesticides and feeding deterrents [22] |

| Nitrogen- and Sulfur-Containing Compounds [21] [22] | Various | Glucosinolates, Alkaloids, Cyanogenic glycosides, Thionine, Defensins [21] [22] | Chemical deterrence against herbivores and pathogens; disruption of microbial integrity; anti-ROS activity [21] [22] |

The production of these SMs is not constant but is dynamically regulated by environmental factors. For instance, abiotic stresses like drought, salinity, and extreme temperatures, as well as biotic stresses from pathogens and herbivores, act as elicitors, triggering sophisticated biosynthetic and signaling networks that lead to the accumulation of defensive compounds [20] [21] [22]. This induced defense mechanism allows plants to allocate resources efficiently, producing necessary chemical defenses only when threatened.

Signaling Molecules and the Regulation of Secondary Metabolism

The biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in response to environmental stimuli is coordinated by a complex network of signaling molecules. These molecules act as messengers, integrating stress signals and activating the transcriptional and biochemical pathways responsible for SM production.

Table 2: Key Signaling Molecules in Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis

| Signaling Molecule | Nature | Role in SM Biosynthesis & Stress Response |

|---|---|---|

| Nitric Oxide (NO) [21] | Gaseous free radical | Modulates enzyme activity and transcription factors; influences SM biosynthetic pathways; provides adaptation under adverse conditions [21]. |

| Hydrogen Sulfide (Hâ‚‚S) [21] | Gaseous molecule | Mitigates abiotic stress by counteracting ROS accumulation; enhances bioactive compound production [21]. |

| Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) [21] | Plant hormone derivative | Elicits production of broad categories of SMs (e.g., rosmarinic acid, terpenoids, indole alkaloids); increases expression of biosynthetic transcription factors and genes [21]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) [21] | Reactive Oxygen Species | Acts as a signaling molecule in stress responses; involved in network of molecules that promote metabolic adjustments and SM accumulation [21]. |

| Calcium (Ca²âº) [21] | Ion | Integral role in stress responses and SM production; works in a network with other signaling molecules [21]. |

The following diagram illustrates the crosstalk between environmental stress, key signaling molecules, and the induction of secondary metabolite biosynthesis pathways:

A critical mechanism by which these signaling molecules exert their effect is through the activation of specific transcription factors such as MYB, bHLH, and WRKY [20]. For example, the WRKY transcription factor is a central regulator that influences the production of alkaloids like taxol in Taxus chinensis and artemisinin in Artemisia annua [21]. This coordinated signaling network ensures that the plant's chemical defense is precisely tailored to the specific environmental challenge.

Methodologies for Studying Secondary Metabolites

Research into the biosynthesis and ecological roles of secondary metabolites relies on a combination of advanced analytical, molecular, and biochemical techniques.

Analytical Techniques for Metabolite Profiling

The comprehensive identification and quantification of SMs are foundational to the field. Key methodologies include:

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS) [23] [24]: This is a core technique for the guided isolation and purification of secondary metabolites. It allows researchers to separate complex mixtures and identify compounds based on their mass-to-charge ratio. It is routinely used for metabolic profiling to compare SM composition across different plant accessions or under varying stress conditions [23] [24].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy [23]: NMR is the definitive method for determining the precise chemical structure of isolated compounds. A full suite of experiments, including 1H, 13C, 1H–1H COSY, HSQC, and HMBC, is used to elucidate molecular structures and confirm absolute configurations [23].

Molecular and Genetic Techniques

Understanding the regulatory networks behind SM biosynthesis requires molecular approaches:

- Gene Expression Analysis: Studying the expression levels of genes involved in biosynthetic pathways (e.g., for transcription factors like WRKY or enzymes like DXS in the terpenoid pathway) under different stress conditions or in response to signaling molecules [21].

- Multivariate Statistical Analysis: Advanced statistical tools such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) are employed to analyze complex metabolite data sets. These methods can identify key biomarkers that differentiate genetic accessions and reveal correlations between specific metabolites (e.g., guayulins and rubber) [24].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: LC/MS-Guided Isolation of Secondary Metabolites from Fungal Culture [23]

- Fermentation and Extraction: Culture the source organism (e.g., Penicillium brevicompactum) in an appropriate liquid medium. After a defined period, separate the mycelia from the broth. Extract the secondary metabolites from the mycelia using an organic solvent like ethyl acetate or methanol, and concentrate under vacuum.

- LC/MS Profiling: Re-dissolve the crude extract and analyze by LC/MS. Use the mass spectral data to guide the fractionation process towards target compounds or compounds with novel masses.

- Chromatographic Purification: Subject the crude extract to successive chromatographic separations. This typically involves:

- Step 1: Open Column Chromatography. Fractionate the extract using a normal-phase (e.g., silica gel) or reversed-phase (e.g., C18) column with a stepwise or gradient elution of solvents of increasing polarity.

- Step 2: Preparative HPLC. Further purify individual fractions using preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a reversed-phase column to obtain pure compounds.

- Structural Elucidation: Analyze pure compounds using NMR spectroscopy (1H, 13C, and 2D experiments like COSY, HSQC, HMBC) and HR-ESIMS to determine their planar and absolute structures.

Protocol: Multivariate Analysis of Metabolite Data for Biomarker Discovery [24]

- Data Collection: Over multiple growing seasons or experiments, compile a comprehensive dataset of metabolite contents (e.g., 82 metabolites across 27 accessions) measured under standardized conditions.

- Data Normalization: Normalize the data to ensure comparability across different metabolites and accessions.

- Statistical Processing:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Perform PCA to reduce the dimensionality of the data and visualize natural groupings among accessions. Identify which metabolites contribute most to the variance between groups.

- Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA): Use HCA to cluster accessions and metabolites based on their abundance profiles, revealing patterns and relationships.

- Spearman Correlation: Calculate correlation coefficients between different metabolites to identify strong positive or negative relationships (e.g., between guayulin A and rubber content).

- Interpretation: Use the results to identify specific metabolites that serve as strong biomarkers for genetic classification or that are strongly linked to traits of economic importance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, materials, and tools essential for experimental research in secondary metabolite biosynthesis and function.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Secondary Metabolite Research

| Item/Biological Material | Function/Application | Example/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Model Producer Organisms | Source of diverse secondary metabolites for isolation and study. | Penicillium brevicompactum MSW10-1 (marine fungus) [23]; Parthenium argentatum (Guayule) [24]. |

| Signaling Molecule Elicitors | To experimentally induce SM biosynthesis pathways in vivo or in vitro. | Sodium nitroprusside (NO donor); NaHS (Hâ‚‚S donor); Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA); Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) [21]. |

| Chromatography Media | For separation and purification of secondary metabolites from crude extracts. | Silica gel, C18 reversed-phase silica for column chromatography; analytical and preparative C18 HPLC columns [23]. |

| Deuterated Solvents | Essential for NMR spectroscopy for structural elucidation of purified compounds. | Deuterated chloroform (CDCl₃), Deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d₆), Deuterated methanol (CD₃OD) [23]. |

| Cell-based Bioassay Systems | For functional evaluation of isolated SMs for biological activity (e.g., therapeutic potential). | HepG2 liver cancer cells for assessing inhibition of hepatic lipogenesis [23]; primary mouse hepatocytes. |

| cudraflavone B | Cudraflavone B - Premium PF|CAS 19275-49-1 | |

| kaempferol 3-O-sophoroside | kaempferol 3-O-sophoroside, CAS:19895-95-5, MF:C27H30O16, MW:610.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Secondary metabolites are central regulators of plant defense, signaling, and environmental adaptation. Their biosynthesis, orchestrated by a complex network of stress-induced signaling molecules and transcription factors, equips plants to survive in a dynamic and challenging environment. The ecological roles of terpenes, phenolics, alkaloids, and sulfur/nitrogen-containing compounds are diverse, ranging from direct toxicity against herbivores to antioxidant activity and structural reinforcement. Modern research, leveraging advanced analytical techniques like LC/MS and NMR alongside multivariate statistical analysis, continues to unravel the complexity of these compounds and their regulatory networks. This deep understanding paves the way for harnessing SMs to improve crop resilience through genetic engineering and to discover novel compounds for pharmaceutical applications, thereby contributing to agricultural sustainability and human health.

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance and the persistent challenge of neoplastic diseases necessitate a continuous pipeline of novel therapeutic agents. Within this context, the symbiotic relationship between medicinal plants and their associated endophytic actinomycetes represents a frontier in the discovery of bioactive secondary metabolites. Secondary metabolites are organic compounds not directly involved in normal growth, development, or reproduction but are crucial for ecological interactions and defense [25] [26]. Actinomycetes, Gram-positive bacteria with high guanine-cytosine content in their DNA, are prolific producers of these compounds, accounting for approximately 45-50% of all discovered bioactive microbial metabolites [25] [27]. Notably, the single genus Streptomyces is responsible for 76% of these compounds, underscoring its dominance in this field [27].

Medicinal plants, shaped by long-term evolutionary pressures, produce a diverse array of unique secondary metabolites. Their endophytic actinomycetes, residing symbiotically within the plant tissues, have adapted to this chemically rich environment and often possess the genetic machinery to produce analogous or entirely novel bioactive compounds [27]. This synergistic relationship creates a powerful dual source for drug leads. However, a significant challenge lies in the fact that under standard laboratory conditions, many of the biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in actinomycetes remain "silent" or "cryptic" [28] [29]. This whitepaper delves into the biodiversity, bioactive potential, and advanced genomic strategies required to unlock the full potential of these natural powerhouses within the broader context of biosynthesis and biogenesis research.

Actinomycetes and medicinal plants are not uniformly distributed; their diversity and chemical potential are heavily influenced by their ecological niches.

2.1 Actinomycetes in Diverse Habitats Actinomycetes exhibit remarkable ecological adaptability, thriving in environments ranging from common soils to extreme habitats. This diversity is a key source of chemical novelty, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Habitat-Specific Diversity of Actinomycetes and Their Bioactive Compounds

| Habitat | Examples of Actinomycete Genera | Reported Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial Soil | Streptomyces, Nocardia | Antibiotics, antimicrobials [25] |

| Rhizosphere Soil | Streptomyces | Antifungal agents, plant growth promotion [25] |

| Marine Ecosystems | Salinispora, Micromonospora | Novel antibiotics, anticancer agents [25] [30] |

| Medicinal Plants (Endophytic) | Streptomyces, Micromonospora, Nocardia, Brevibacterium, Leifsonia | Broad-spectrum antimicrobial, anticancer [25] [27] [31] |

| Extreme Environments (e.g., Hypersaline, Desert) | Streptomyces albidoflavus, S. griseoflavus | Antibacterial, antifungal [25] |

The isolation of rare genera like Brevibacterium, Microbacterium, and Leifsonia xyli from medicinal plants such as Mirabilis jalapa and Clerodendrum colebrookianum highlights that these plants are reservoirs of untapped microbial diversity [31].

2.2 Endophytic Actinomycetes in Medicinal Plants Endophytic actinomycetes colonize the internal tissues of plants without causing disease. Their distribution within the plant is not random; they are most frequently isolated from roots, followed by stems, with leaves yielding the fewest isolates [27]. This likely reflects the soil as the primary source of colonization. The choice of isolation media is critical for capturing this diversity, with Starch Casein Nitrate Agar (SCNA), Tap Water Yeast Extract Agar (TWYE), and Humic Acid Vitamin B (HV) agar being among the most effective [27] [31].

Experimentation and Analytical Methodologies

A standardized, rigorous protocol is essential for the isolation, identification, and screening of endophytic actinomycetes.

3.1 Protocol for Isolation and Screening of Endophytic Actinomycetes

- 1. Sample Collection and Surface Sterilization: Collect fresh, healthy plant organs (roots, stems, leaves). Wash in running tap water and subject to sequential surface sterilization: immersion in 70% ethanol (3 min), followed by 0.4% sodium hypochlorite (1 min), and another rinse in 70% ethanol (2 min), concluding with three sterile distilled water washes [31].

- 2. Efficacy Validation: To confirm surface sterilization efficacy, imprint the sterilized tissue on an agar plate and inoculate the last wash water onto a control plate. The absence of microbial growth confirms that isolated microbes are true endophytes [27] [31].

- 3. Isolation and Cultivation: Aseptically macerate the surface-sterilized tissue and plate onto selective media like SCNA or AIA. Supplement media with antifungal agents (e.g., cycloheximide, 50-100 µg/mL) and antibacterial agents (e.g., nalidixic acid, 60 µg/mL) to inhibit the growth of fungi and fast-growing bacteria, respectively [27] [31]. Incubate plates at 26-28°C for 15-30 days.

- 4. Purification and Morphological Identification: Sub-culture distinct colonies showing actinomycete morphology (e.g., compact, filamentous, with aerial hyphae). Preliminary identification is based on characteristics of aerial and substrate mycelia, sporulation, and pigment production [31].

- 5. Molecular Identification: Extract genomic DNA and amplify the 16S rRNA gene for sequencing. This allows for accurate phylogenetic classification. For deeper genomic analysis, Whole Genome Sequencing can be performed [28].

- 6. Screening for Bioactivity: Conduct initial antimicrobial screening using the agar well diffusion method. Culture actinomycete isolates in broth, harvest cell-free supernatant, and place it in wells seeded with test pathogens (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Candida albicans) [31]. The presence of an inhibition zone indicates antimicrobial activity.

3.2 The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents Table 2: Key Reagents for Isolation and Characterization of Endophytic Actinomycetes

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Surface Sterilants (70% Ethanol, NaOCl) | Eliminates epiphytic microorganisms from plant tissue surfaces [27] [31]. |

| Selective Media (SCNA, AIA, TWYE) | Provides nutrients selective for actinomycete growth while suppressing other microbes [27] [31]. |

| Antifungal Agents (Nystatin, Cycloheximide) | Inhibits fungal contamination in culture plates [27]. |

| Antibacterial Agents (Nalidixic Acid) | Suppresses the growth of Gram-negative bacteria during isolation [31]. |

| Genomic DNA Extraction Kit | For obtaining high-quality DNA for PCR and sequencing [28]. |

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | Amplification of the conserved 16S rRNA gene for phylogenetic analysis [31]. |

Key Bioactive Compounds and Their Biosynthetic Pathways

Actinomycetes are a primary source of clinically indispensable compounds. Their secondary metabolites are synthesized by massive enzyme complexes encoded by BGCs, which are often silent under laboratory conditions.

4.1 Major Classes of Bioactive Metabolites

- Antitumor Compounds: Many clinically used chemotherapeutics are derived from actinomycetes. Doxorubicin and Mitomycin C are potent antitumor antibiotics that function by intercalating into DNA and causing cross-linking, respectively, thereby disrupting DNA replication and transcription and inducing apoptosis [26] [32].

- Antimicrobial Compounds: The "Golden Age of Antibiotics" was built upon discoveries from actinomycetes. Streptomycin (from S. griseus), oxytetracycline, and erythromycin are classic examples that target bacterial protein synthesis [26] [32].

- Other Bioactivities: Metabolites like avermectin exhibit broad-spectrum antiparasitic activity, while others show antioxidant, antihyperglycemic, and anti-inflammatory properties [26] [32].

4.2 Activating Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters Genome mining has revealed that a typical Streptomyces genome harbors 25-50 BGCs, yet up to 90% remain silent in standard lab cultures [28] [29]. Several innovative strategies are employed to awaken this cryptic potential, with coculture being a particularly effective method that mimics natural ecological competition.

Diagram 1: Strategies to activate silent gene clusters for novel compound discovery. Adapted from [29] and [28].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Analysis of Bioactivity

Systematic screening provides quantitative evidence of the bioactivity potential inherent in actinomycetes, especially those isolated from medicinal plants.

Table 3: Quantitative Summary of Bioactive Potential from Select Studies

| Study Focus | Isolation Source / Strategy | Key Quantitative Findings | Identified Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endophytic Actinomycetes from Medicinal Plants [31] | 7 medicinal plants from India | 42 total isolates; 22 (52.3%) showed antimicrobial activity. Highest isolation rate from roots (52.3%). | Broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against human pathogens; presence of PKS-I and NRPS biosynthetic genes. |

| Genomic Potential of Actinomycetes [28] | 211 genomes from diverse environments (mangroves, soil, marine sponges) | All 211 genomes met high-quality standards (≥95% completeness, <5% contamination). 32 strains were potential new species. | Dataset reveals extensive, unexplored smBGC diversity for novel compound discovery. |

| Antitumor Metabolites Review (2019-2024) [26] [32] | Systematic literature review | 87 eligible studies identified diverse structural classes: polyketides, non-ribosomal peptides, alkaloids, and terpenoids. | Potent anticancer properties via apoptosis induction, proliferation inhibition, and disruption of tumor microenvironment. |

The alliance between medicinal plants and endophytic actinomycetes constitutes a formidable and largely untapped reservoir for the biogenesis of novel secondary metabolites. The path forward requires an integrated, multidisciplinary approach. First, the exploration of underexplored and extreme ecosystems must be intensified to isolate novel actinomycete taxa. Second, high-throughput genome mining must become standard practice to map the vast landscape of silent BGCs. Finally, innovative activation strategies, particularly coculture and precision genetic engineering, are critical to translate genetic potential into chemical reality. By leveraging these advanced methodologies, researchers can systematically mine these powerhouses of bioactive compounds, paving the way for the next generation of therapeutics to address pressing global health challenges.

Harnessing Modern Technologies for Metabolite Discovery and Production

Genome Mining and In Silico Prediction of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)

In the context of secondary metabolites research, natural products represent an unparalleled source of bioactive compounds, many of which have found critical applications in medicine as antibiotics, anticancer agents, and immunosuppressants [33] [34]. These chemically diverse compounds are synthesized by bacteria, fungi, plants, and other organisms through genetically encoded biosynthetic pathways, typically organized as biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [35] [33]. The emerging field of genome mining has revolutionized natural product discovery by leveraging computational tools to identify and characterize BGCs directly from genomic data, thereby uncovering the vast cryptic metabolic potential that far exceeds what is observed under laboratory conditions [36] [33].

This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and tools for in silico prediction of BGCs, framing these computational approaches within the broader thesis of secondary metabolite biogenesis and their applications in drug discovery. As the pharmaceutical industry faces challenges including antibiotic resistance and high rediscovery rates of known compounds, genome mining provides a powerful strategy to prioritize novel chemical entities for experimental characterization [35] [37].

Computational Tools for BGC Identification and Analysis

The exponential growth of genomic sequencing data has propelled the development of sophisticated bioinformatic tools that identify BGCs based on our understanding of biosynthetic logic [33]. These tools primarily rely on homology to characterized pathways or employ machine learning approaches to detect novel BGC classes.

Table 1: Major Computational Tools for BGC Prediction and Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Algorithm | Key Features | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [38] [39] | Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) | Identifies BGCs, compares to known clusters, predicts core structures | Generalist: Multiple BGC classes |

| PRISM [37] [38] | HMMs + Chemical graph-based prediction | Predicts secondary metabolite structures from BGC sequences | Generalist: Focus on structural prediction |

| DeepBGC [37] [38] | Bidirectional LSTM + Random Forest | Uses machine learning for BGC identification and product class prediction | Generalist: BGC identification & classification |

| GECCO [38] | Conditional Random Fields | Identifies BGCs using feature selection based on Fisher's exact test | Generalist: Particularly for bacterial genomes |

| BAGEL4 [38] | Protein motif search + BLAST | Specialized for bacteriocin identification | Class-specific: RiPPs (Bacteriocins) |

| RODEO [38] | HMM + Heuristic scoring + SVM | Identifies lasso peptide BGCs and predicts precursor peptides | Class-specific: RiPPs (Lasso peptides) |

| ARTS 2.0 [38] | HMMs + Genomic context analysis | Identifies antibiotic resistance genes within BGCs | Target-based: Antibiotic discovery |

| ClusterFinder [38] | Two-state HMM | Probabilistic identification of BGCs based on biosynthetic signatures | Generalist: Broad BGC detection |

Specialized Databases for BGC Analysis

Table 2: Key Databases for BGC and Natural Product Research

| Database | Content Scope | Key Features | Utility in Genome Mining |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIBiG [37] [39] | Curated BGCs with known products | Minimum information standard for BGC annotation | Reference database for known BGCs |

| ABC-HuMi [38] | BGCs from human microbiome | Interactive platform for five human body sites | Human microbiome-focused discovery |

| sBGC-hm [38] | BGCs from human gut microbiome | Specialized catalog of gut-derived BGCs | Gastrointestinal microbiome research |

| IMG/ABC [34] | Microbial BGCs from diverse environments | Large-scale database linking BGCs to metabolites | Comparative analysis across ecosystems |

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Core Genome Mining Protocol

A standard workflow for BGC discovery integrates multiple computational tools to progress from raw genomic data to prioritized candidates for experimental validation [39]. The following protocol outlines key steps for comprehensive BGC analysis:

Genome Acquisition and Preparation: Obtain genomic sequences in FASTA or GenBank format. For metagenomic studies, this step involves assembly of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from sequencing reads [38] [40].

BGC Identification: Process genomic data through BGC prediction tools, with antiSMASH serving as the most widely adopted platform for initial detection [39]. antiSMASH identifies BGCs based on HMM profiles of core biosynthetic enzymes and additional features including Pfam domains and cluster boundaries [38].

Feature Extraction and Annotation: Decompose identified BGCs into features describing gene components and biosynthetic capabilities. This includes:

Comparative Analysis and Prioritization: Compare identified BGCs against reference databases (e.g., MIBiG) to assess novelty [39]. Tools like BiG-SCAPE and BiG-FAM facilitate clustering of BGCs into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) based on sequence similarity, enabling evolutionary analyses and prioritization of divergent clusters [38].

Structure and Activity Prediction: For prioritized BGCs, utilize tools like PRISM to predict encoded chemical structures [38]. Machine learning classifiers can predict bioactivity (e.g., antibacterial, antifungal) directly from BGC features, achieving accuracies up to 80% for certain activity classes [37].

Targeted Genome Mining Approaches

Beyond general BGC detection, specialized mining strategies leverage particular genetic elements to discover compounds with desired properties:

Resistance Gene-Based Mining: This approach targets BGCs containing self-resistance genes, particularly effective for antibiotic discovery. Genes conferring resistance through target duplication or modification are often co-localized with their corresponding biosynthetic machinery [33]. The ARTS 2.0 tool specializes in identifying BGCs with resistance genes through detection of physical proximity, gene duplication, and horizontal gene transfer events [38].

Phylogeny-Guided Mining: This strategy focuses on taxonomic groups known for prolific metabolite production or understudied phyla with biosynthetic potential. For example, Planctomycetota have been found to contain numerous divergent BGCs, indicating untapped chemical diversity [40].

Metabolomics-Integrated Mining: Coupling genomic data with mass spectrometry (MS) through tools like NPLinker and NPOmix enables connection of BGCs to their metabolic products, facilitating dereplication and structural elucidation [38] [33].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for genome mining and BGC prediction, integrating both general and specialized approaches.

Machine Learning in BGC Prediction and Bioactivity Assessment

The application of artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning algorithms, has significantly enhanced both the speed and precision of BGC mining [35]. ML approaches address critical bottlenecks in natural product discovery, particularly in predicting the biological activity of encoded compounds prior to costly experimental characterization [37].

Machine Learning Framework for Bioactivity Prediction

A robust ML framework for BGC bioactivity prediction involves the following methodological components [37]:

Training Dataset Assembly: Curate a high-quality dataset of known BGCs paired with their experimentally determined bioactivities. The MIBiG database serves as an essential resource, supplemented with literature-derived activity annotations [37]. Activities are typically recorded as binary values (active/inactive) for specific biological effects (e.g., antibacterial, antifungal, cytotoxic).

Feature Engineering: Represent BGCs as feature vectors based on:

- Pfam domain counts and sub-PFAM classifications via sequence similarity networks

- smCOG annotations and CDs motifs

- PKS/NRPS monomer predictions

- Resistance genes identified through RGI analysis This process typically generates thousands of features (e.g., 1809 features for 1003 BGCs) [37].