Beyond Nature's Blueprint: Modern Strategies to Optimize the Chemical Accessibility of Natural Product Leads

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on overcoming the primary challenge in natural product-based drug discovery: the poor chemical accessibility of complex natural leads.

Beyond Nature's Blueprint: Modern Strategies to Optimize the Chemical Accessibility of Natural Product Leads

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on overcoming the primary challenge in natural product-based drug discovery: the poor chemical accessibility of complex natural leads. It explores the foundational reasons why these molecules are often difficult to synthesize, details modern computational and experimental methodologies—including fragment-based design, SCAR by Space, and in silico tools like WHALES—to simplify structures while preserving bioactivity. The content further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios for ADMET optimization and provides frameworks for validating synthetic feasibility and comparing lead candidates. By integrating these strategies, scientists can more effectively translate promising natural product hits into viable, synthetically accessible drug candidates.

The Natural Product Paradox: Unlocking Bioactivity While Overcoming Synthetic Complexity

Why Chemical Accessibility is a Critical Bottleneck in NP Drug Discovery

FAQs: Understanding the Chemical Accessibility Bottleneck

FAQ 1: What is meant by "chemical accessibility" in natural product drug discovery? Chemical accessibility refers to the ability to obtain a natural product compound in sufficient quantity and purity for comprehensive biological testing and subsequent development. This encompasses the entire process from sourcing the raw biological material, isolating the pure compound from complex mixtures, to having enough material for hit confirmation, lead optimization, and pre-clinical studies. Challenges in any of these steps can halt an otherwise promising drug discovery program [1].

FAQ 2: Why is sourcing natural products a major challenge? Sourcing presents multiple hurdles. The collection of plant or marine organisms can lead to overharvesting and biodiversity loss, raising significant ecological and sustainability concerns. Furthermore, many source organisms, particularly microorganisms from extreme environments, are uncultivable under standard laboratory conditions, making their metabolic products inaccessible. Legal complexities, such as those governed by the Nagoya Protocol, also regulate international access to genetic resources and the fair sharing of benefits, which can complicate collaborations and sourcing from biodiversity-rich regions [2] [3].

FAQ 3: What are the specific technical barriers in the isolation and purification of natural products? The path from a crude extract to a pure, characterized compound is fraught with difficulties. Crude biological extracts are inherently complex mixtures of many compounds, making the separation of individual pure substances a laborious, multi-step process. The quantity of the target compound isolated from the natural source is often minute (milligrams or less), which is insufficient for full biological profiling and development. Additionally, the process of dereplication—the early identification of known compounds to avoid re-isolation—is crucial for efficiency but remains a significant technical bottleneck [1] [4].

FAQ 4: How does chemical accessibility impact the progression of a natural product lead? A lack of chemical accessibility directly translates to a high attrition rate in natural product-based drug discovery. Many biologically active extracts identified in initial screenings never progress to a identified lead compound because the active constituent cannot be isolated in usable quantities. Even when a potent lead is identified, insufficient material can prevent the thorough evaluation of its mechanism of action, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic properties, and can stall programs aimed at synthesizing simpler or more potent analogues [1] [3].

FAQ 5: What modern strategies are being used to overcome supply bottlenecks? The field is adopting several innovative strategies to address supply issues:

- Heterologous Expression & Synthetic Biology: Introducing biosynthetic gene clusters into genetically tractable host organisms (like Streptomyces species) to produce the compound through fermentation [5].

- Genome Mining: Using genomic data to identify biosynthetic pathways for novel compounds and then activating them in native or heterologous hosts [2] [5].

- Total Synthesis & Analog Design: Developing synthetic routes to produce the natural product or designing simpler "pseudo-natural products" that retain the core bioactive structure but are more synthetically accessible [6].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent or Vanishing Bioactivity During Isolation

Issue: An extract shows promising activity in a primary bioassay, but the activity is lost, diminishes, or becomes inconsistent as you fractionate and purify the sample.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Synergistic Effects: The bioactivity is the result of multiple compounds working together, which are separated during purification. | Recombine purified fractions in different combinations and re-test for activity restoration. | Consider developing a standardized extract instead of pursuing a single compound. Alternatively, focus on a defined mixture of fractions [3]. |

| Compound Instability: The active compound is degrading under the isolation conditions (e.g., pH, light, temperature). | Re-analyze active fractions by LC-MS immediately after purification and again after 24-48 hours to look for decomposition products. | Optimize isolation protocols to use protective conditions (e.g., under nitrogen, in amber glass, at lower temperatures). Add stabilizers if compatible with the assay. |

| Non-Specific Binding: The active compound is binding to labware (e.g., plastic tubes, filtration membranes) or stationary phases during chromatography. | Use different types of labware (e.g., glass, low-binding plastics). Analyze the flow-through and washings from solid-phase extraction for activity. | Use silanized glassware or low-binding plastics. Change chromatography media (e.g., switch from C18 to polymer-based). |

Problem 2: Overcoming the "Dereplication Wall"

Issue: After significant effort in isolation, you find that your pure compound is already known from published literature, leading to wasted resources.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Pre-screening: Relying solely on a single database or analytical technique (e.g., LC-UV) for dereplication. | Perform high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) to determine molecular formula and search against specialized NP databases. Use MS/MS molecular networking. | Implement a multi-technique dereplication workflow early in the process. Combine HR-MS, MS/MS fragmentation, and NMR profiling (even on partially purified samples) [4]. |

| Inefficient Use of Databases: Not querying comprehensive or specialized natural product databases. | Search the compound's molecular formula or predicted structure in several databases (e.g., GNPS, NPASS, PubChem) [4]. | Integrate in-silico tools and databases into the discovery pipeline. Use tools like the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform for comparative analysis of MS/MS data [4]. |

Problem 3: Low Titer in Heterologous Expression

Issue: After successfully cloning a biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) into a heterologous host, the production titer of the target natural product is negligible or very low.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Gene Expression: The native promoters of the BGC are not recognized efficiently by the heterologous host's transcriptional machinery. | Use RT-PCR to check the transcription levels of key biosynthetic genes. Compare them to levels in the native producer if possible [5]. | Refactor the gene cluster: Replace native promoters with strong, constitutive promoters (e.g., ErmE*) that are well-known in the host system. |

| Absence of Pathway-Specific Regulators: The positive regulatory gene(s) that activate the BGC in the native host may not be present or functional. | Check the BGC sequence for putative regulatory genes. Overexpress them in the heterologous host and monitor production. | Co-express positive regulators: Clone and express the pathway-specific regulatory gene(s) alongside the BGC in the heterologous host [5]. |

| Bottleneck in Biosynthesis: A single enzyme in the pathway may be poorly expressed or inefficient, causing a metabolic bottleneck. | Use RT-PCR and/or proteomics to identify genes/proteins with very low expression levels compared to the rest of the pathway. | Identify and overcome the bottleneck: Co-express the rate-limiting gene(s). For example, co-overexpression of fdmR1 (regulator) and fdmC (ketoreductase) was crucial for improving fredericamycin A production in S. lividans [5]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: An Integrated Dereplication Workflow for Crude Extracts

Objective: To rapidly identify known compounds in a biologically active crude extract before committing to large-scale isolation.

Materials:

- Equipment: UHPLC system coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF or Orbitrap) with MS/MS capability; NMR spectrometer (e.g., 600 MHz).

- Software: Molecular networking software (e.g., GNPS), NMR processing software, database access (e.g., SciFinder, AntiBase, GNPS).

- Reagents: LC-MS grade solvents (MeCN, H2O, formic acid); deuterated NMR solvents (e.g., CD3OD, DMSO-d6).

Methodology:

- LC-HRMS/MS Analysis:

- Inject the crude extract onto the UHPLC-HRMS/MS system.

- Acquire data in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode, collecting both full-scan MS (for accurate mass) and MS/MS fragmentation data for all major peaks.

- Molecular Networking:

- Process the MS/MS data file and upload it to the GNPS platform.

- Create a molecular network to visualize the chemical families present in your extract. This helps cluster related molecules and can quickly point to known compound families.

- Database Interrogation:

- Use the accurate mass and isotope pattern from the HR-MS data to calculate possible molecular formulas.

- Search these formulas and the MS/MS fragmentation spectra against in-silico and curated spectral libraries within GNPS and other databases.

- 1D NMR Profiling:

- Prepare a concentrated sample of the crude extract and acquire a 1H NMR spectrum.

- Identify characteristic signals (e.g., aromatic protons, olefinic protons, methyl group patterns) that can help narrow down the class of compound (e.g., flavonoid, terpene, alkaloid).

- Data Triangulation:

- Correlate the findings from the MS, MS/MS, and NMR data. A putative identification is highly confident when consistent results are obtained from all three techniques. Proceed to isolation only for compounds that cannot be identified as known [4].

Protocol 2: A Workflow for the Heterologous Expression of a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

Objective: To produce a target natural product by expressing its BGC in a genetically tractable heterologous host.

Materials:

- Bacterial Strains: Source organism (native producer); heterologous host (e.g., Streptomyces albus, S. lividans); E. coli for cloning.

- Vectors: A suitable shuttle vector (e.g., BAC, cosmic) capable of carrying the large BGC DNA insert.

- Culture Media: Appropriate media for growing all bacterial strains (e.g., LB, R5, SFM).

- Equipment: Fermenters or shake flasks, HPLC-MS for metabolite analysis, PCR machine.

Methodology:

- BGC Identification & Capture:

- Identify the target BGC through genome sequencing and bioinformatics tools (e.g., antiSMASH).

- Isolate the intact BGC from the native producer's genomic DNA and clone it into the expression vector.

- Vector Engineering (Refactoring - Optional but Recommended):

- Replace native promoters of the core biosynthetic genes with strong, constitutive promoters suitable for the heterologous host.

- Ensure that the regulatory genes within the BGC are intact and functional, or plan to co-express them.

- Host Transformation & Screening:

- Introduce the constructed vector into the heterologous host via conjugation or protoplast transformation.

- Screen successful exconjugants for the presence of the entire BGC using PCR.

- Fermentation & Metabolite Analysis:

- Ferment positive clones in appropriate media and conditions. Include the empty-vector host as a negative control.

- Extract the culture broth and mycelia with organic solvents.

- Analyze the extracts using HPLC-MS and compare the chromatograms to that of the native producer and the negative control to detect production of the target compound.

- Titer Improvement:

- If the titer is low, diagnose bottlenecks using RT-PCR to check gene expression.

- Co-express putative positive regulators or rate-limiting enzymes.

- Optimize fermentation conditions (media, temperature, duration) [5].

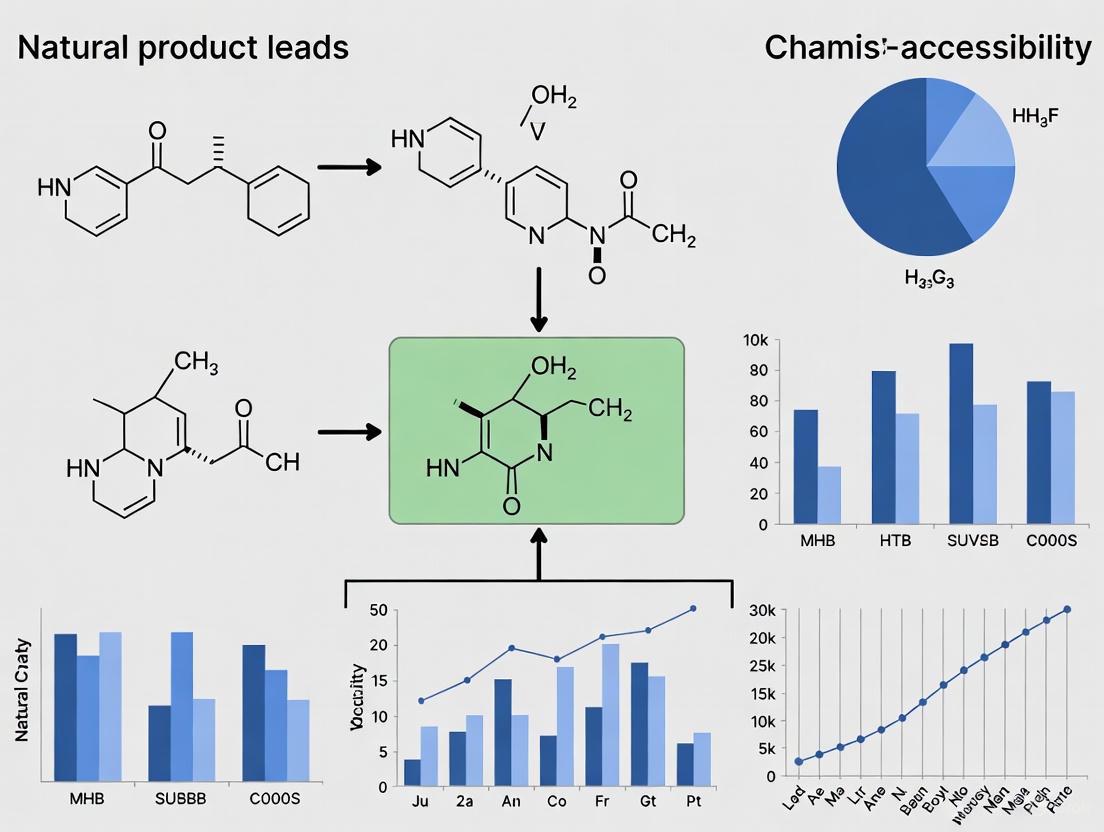

Visualizing the Workflow: From Source to Lead

The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage process of natural product drug discovery, highlighting the critical points where chemical accessibility can become a bottleneck.

Diagram: NP Drug Discovery Path and Bottlenecks. This flowchart outlines the key stages of natural product-based drug discovery and pinpoints where major chemical accessibility bottlenecks occur, from sourcing to scalable production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents, tools, and technologies used to navigate the challenges of chemical accessibility in natural product research.

| Tool/Reagent | Function & Application in NP Research |

|---|---|

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HR-MS) | Determines the exact mass of a compound, allowing for the calculation of its molecular formula. Critical for the first step in dereplication and structure elucidation [4]. |

| Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) | An online platform that allows for the creation of molecular networks from MS/MS data. It enables the rapid comparison of your compounds against a vast library of known spectra, drastically improving dereplication efficiency [4]. |

| Heterologous Host Strains (e.g., S. albus J1074) | Genetically tractable microbial chassis used to express biosynthetic gene clusters from uncultivable or slow-growing source organisms. This is a key strategy for solving sustainable supply issues [5]. |

| Computer-Assisted Structure Elucidation (CASE) | Software that uses NMR and other spectroscopic data to propose chemical structures. It helps to accelerate the challenging process of determining the structure of novel compounds, especially those with complex stereochemistry [4]. |

| antiSMASH | A bioinformatics tool for the genome-wide identification, annotation, and analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters. It is the starting point for most modern genome-mining campaigns [2]. |

| Synthetic Biology Vectors (BACs, Cosmids) | Large-capacity cloning vectors capable of holding the entire DNA sequence of a biosynthetic gene cluster (often 50-150 kb) for transfer into a heterologous host [5]. |

| Constitutive Promoters (e.g., ErmE*) | Strong, always-on promoters used in synthetic biology to "refactor" biosynthetic gene clusters, ensuring high expression of pathway genes in heterologous hosts where native regulators may not function [5]. |

| 3,5-Dihydroxybenzoic Acid | 3,5-Dihydroxybenzoic Acid, CAS:99-10-5, MF:C7H6O4, MW:154.12 g/mol |

| 3-O-Methyltolcapone | 3-O-Methyltolcapone, CAS:134612-80-9, MF:C15H13NO5, MW:287.27 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides

Structural Intricacy

Problem: Difficulty in determining the complete molecular structure of a newly isolated natural product, especially when dealing with large, complex ring systems or flexible chains.

Solution: Employ advanced structural elucidation techniques that can handle complexity and require minimal material.

- Guide: Using Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED) for Complex Structures

- Background: Traditional methods like NMR spectroscopy can struggle with molecules containing distal stereocenters interrupted by rigid substructures bearing multiple rotatable bonds, often making it impossible to determine the relative stereochemistry of distal fragments [7]. X-ray crystallography is the gold standard but often requires large, pristine crystals that are difficult to obtain from scarce natural products [7].

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Purify the natural product to homogeneity. Lyophilize the powder sample [7].

- Grid Preparation: Apply the powder to a transmission electron microscopy (TEM) grid.

- Screening: Use electron micrographs to identify crystalline domains within the lyophilized powder [7].

- Data Collection: Collect diffraction movies from sub-micron-sized crystals. Merge data from multiple movies to enhance resolution (e.g., to 0.85 Ã…) [7].

- Structure Solution: Use ab initio structure elucidation methods to solve the structure directly from the MicroED data, assigning relative and absolute configuration unambiguously [7].

- Expected Outcome: Unambiguous determination of a novel natural product's structure, including relative stereochemistries, within hours and from a single data collection session [7].

Stereochemistry

Problem: Ambiguous or incorrect assignment of stereocenters in a natural product, leading to failed biological activity replication.

Solution: Combine computational predictions with experimental validation.

- Guide: Correcting Stereochemistry with Machine Learning and Experimental Validation

- Background: Stereochemistry is critical for the biological activity of natural products. Traditional assignment via NMR can be ambiguous, and errors can persist in the literature for decades [7]. Machine learning models now offer a powerful tool for prediction.

- Protocol:

- Input Preparation: Generate the absolute SMILES notation (excluding stereochemical information) of the natural product [8].

- Machine Learning Prediction: Process the SMILES string through a specialized language model like NPstereo, which is trained on the COCONUT database to predict stereochemical configuration [8].

- Output Analysis: The model will return an isomeric SMILES notation containing predicted stereochemical information with high per-stereocenter accuracy [8].

- Experimental Validation: Use the prediction to guide targeted synthesis of the proposed stereoisomer or confirm the assignment using a technique like MicroED [7].

- Expected Outcome: A high-confidence stereochemical assignment for a newly discovered natural product or the correction of an existing misassignment [8].

Low Natural Abundance

Problem: The natural source produces the target compound in extremely low yields, insufficient for drug development or comprehensive bioactivity testing.

Solution: Bypass the native producer using synthetic biology and heterologous expression.

- Guide: Activating Silent Gene Clusters in Heterologous Hosts

- Background: Often, the biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) for valuable natural products are "silent" under laboratory conditions or produced in minuscule quantities by slow-growing native organisms [5]. Heterologous expression involves transferring the BGC into a genetically tractable host for optimized production.

- Protocol:

- BGC Identification: Mine the genome of the native producer to identify the target BGC [7] [5].

- Host Selection: Choose a well-characterized heterologous host (e.g., Aspergillus nidulans for fungi, Streptomyces albus for bacteria) known for high production yields and genetic accessibility [7] [5].

- Cluster Refactoring: Clone the entire BGC into an appropriate expression vector. This may involve replacing native promoters with strong, constitutive ones to boost expression [5].

- Regulatory Gene Co-expression: Identify and co-express positive pathway-specific regulatory genes (e.g., SARP family regulators). This is often crucial for activating the entire BGC in the new host [5].

- Identify Bottlenecks: Use RT-PCR to compare transcription levels of key biosynthetic genes between the native and heterologous producers. Co-overexpress any genes that are poorly transcribed in the heterologous system [5].

- Fermentation & Extraction: Ferment the engineered host and extract the target compound.

- Expected Outcome: Significantly improved titers of the target natural product (e.g., from mg/L to g/L scales), enabling further studies [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is structural elucidation still a major bottleneck in natural product discovery? Structural elucidation remains challenging due to the intrinsic complexity of natural products. They often contain multiple chiral centers, large, fused ring systems, and flexible chains that make determining relative stereochemistry, especially between distal parts of the molecule, difficult with NMR alone. Furthermore, traditional X-ray crystallography requires large, well-formed crystals that are often impossible to grow with the limited quantities of material typically isolated [7].

FAQ 2: Our lead natural product has promising activity but poor solubility and metabolic stability. What are our options? This is a common challenge. The primary strategy is lead optimization through medicinal chemistry [9]. This involves:

- SAR Studies: Creating synthetic analogues to understand which parts of the molecule are critical for activity.

- Functional Group Manipulation: Modifying specific groups to improve ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties. This can include altering lipophilicity, introducing solubilizing groups, or blocking metabolic hot spots [9] [10]. The goal is to enhance drug efficacy and optimize the pharmacokinetic profile while retaining the core bioactive pharmacophore [9].

FAQ 3: We've identified a promising biosynthetic gene cluster, but it's silent in the lab. How can we activate it? Two primary strategies exist:

- Epigenetic Approaches: Modify culture conditions by adding small-molecule elicitors, using co-culture with other microbes, or varying nutritional and environmental stressors to trigger natural defense and production responses [5].

- Genomics-Based Approaches: This is often more direct. It involves overexpressing positive pathway-specific regulators within the native host or, more effectively, cloning the entire cluster into a heterologous host and co-expressing these regulators there. This severs the cluster from potential native repression and places it under strong, artificial control [5].

FAQ 4: How do natural products and synthetic compounds compare in terms of chemical space and drug discovery potential? Chemoinformatic analyses show that natural products (NPs) occupy a distinct and more diverse region of chemical space compared to synthetic compounds (SCs). NPs are generally larger, more complex, have more chiral centers and oxygen atoms, and contain more non-aromatic rings. SCs, while more numerous, often have higher aromatic ring content and nitrogen/sulfur atoms. Critically, NPs have higher "biological relevance" due to their evolution to interact with biological macromolecules, which is why over 60% of pharmaceuticals are NP-derived or inspired [11] [12].

Table 1: Contribution of Natural Products to Approved Drugs (1981-2010) [9]

| Category | Definition | All Small-Molecule Drugs (%) | Anticancer Drugs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Product (N) | Unmodified natural product | 5.5% | 11.1% |

| Natural Product Derived (ND) | Semi-synthetic derivative | 27.9% | 32.3% |

| Synthetic, NP Pharmacophore (S*) | Synthetic, with NP-inspired active moiety | 5.1% | 11.1% |

| Totally Synthetic (S) | No NP inspiration | 36.0% | 20.2% |

| Total NP-Inspired | Sum of N, ND, S* | ~38.5% | ~54.5% |

Table 2: Comparison of Key Properties: Natural Products vs. Synthetic Compounds [12]

| Property | Natural Products (NPs) | Synthetic Compounds (SCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Larger and increasing over time (MW, volume, etc.) | Smaller, constrained by drug-like rules |

| Rings | More rings, predominantly non-aromatic | Fewer rings, high proportion of aromatic rings |

| Structural Diversity | Higher scaffold diversity and complexity | Broader synthetic diversity but less unique |

| Biological Relevance | Higher, evolved to interact with biomolecules | Lower, despite larger chemical libraries |

| Chemical Space | More diverse and expanding | More concentrated and constrained |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Overcoming NP Research Barriers

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Host Strains | Genetically tractable chassis for expressing foreign BGCs. | Aspergillus nidulans A1145 ΔEMΔST for fungal clusters; Streptomyces albus for actinobacterial clusters [7] [5]. |

| Pathway-Specific Regulatory Genes | Positive regulators that activate transcription of silent BGCs. | Overexpression of SARP family regulators (e.g., fdmR1) to boost titers of target compounds like Fredericamycin A [5]. |

| Constitutive Promoters | Strong, always-on promoters to drive high-level gene expression. | ErmE* promoter for constitutive expression of biosynthetic or regulatory genes in heterologous hosts [5]. |

| MicroED Platform | Cryo-EM method for determining structures from nano-crystals. | Ab initio structural elucidation of new natural products like Py-469, solving stereochemistry where NMR fails [7]. |

| Machine Learning Models (e.g., NPstereo) | In-silico prediction of stereochemical configuration. | Assigning or correcting the stereochemistry of newly discovered NPs from their planar structure [8]. |

| Specialized Compound Databases | Curated collections of NP structures for mining and prediction. | COCONUT database for training ML models; Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP) for chemoinformatic analysis [12] [8]. |

| Montelukast-d6 | Montelukast-d6, MF:C35H36ClNO3S, MW:592.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pradimicin Q | Pradimicin Q, CAS:141869-53-6, MF:C24H16O10, MW:464.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: My natural product lead shows high structural complexity and poor synthetic tractability. How can I proceed with optimization?

Answer: This is a common challenge. The biological relevance of the natural product (NP) scaffold often justifies the optimization effort. Several strategies can be employed:

- Apply Scaffold Simplification: Use Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS) to identify and synthesize the core, biologically active scaffold of the NP, reducing synthetic complexity while retaining function [6]. For instance, complex meroterpenoid NPs like aureol have been used to generate synthetic analogue libraries for SAR studies, leading to simplified compounds with improved antibacterial and antiproliferative activities [13].

- Utilize a Pseudo-Natural Product Approach: Deconstruct the NP into its core fragments and recombine them into novel, synthetically accessible "pseudo-NP" scaffolds that explore new biologically relevant chemical space not accessible through biosynthesis [14] [6].

- Employ Function-Oriented Synthesis (FOS): Design and synthesize simpler structures that retain the function of the original, complex NP. This was demonstrated with the design of trioxacarcin ADC payload analogues, which maintained potent antitumour activity but were more synthetically feasible than the parent NP, trioxacarcin A [13] [6].

FAQ: My NP-derived compound has promising potency but poor pharmacokinetic (PK) properties. What are my options?

Answer: Poor PK is a frequent hurdle that can often be overcome through rational structural modification.

- Systematic Analogue Synthesis: Create a library of analogues based on the NP scaffold to establish a structure-activity relationship (SAR) and a structure-pharmacokinetic relationship (SPR). A study on the phenylpropanoid isodaphnetin used rational design to create an analogue library, identifying a lead compound with a 7,400-fold improvement in potency and good oral bioavailability [13].

- Focus on Alkaloid Modifications: Alkaloid scaffolds often require optimization for selectivity and PK. For example, libraries of "ring-distorted" cinchona alkaloid derivatives have been prepared and screened to identify compounds with improved therapeutic profiles and novel mechanisms of action [13].

FAQ: I am struggling to find comprehensive data on natural product structures. Where should I look?

Answer: A significant number of NP databases exist, but their accessibility and focus vary. The table below summarizes key open-access resources [15].

Table 1: Selected Open-Access Natural Products Databases

| Database Name | Type / Focus | Approximate Number of Compounds | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| COCONUT | Generalistic Collection | > 400,000 | The largest open collection of non-redundant NPs; available as a downloadable dataset [15]. |

| Various Resources | Thematic (e.g., Traditional Medicine, Geographic) | Varies | Many thematic databases focus on specific geographic regions, taxonomic groups, or traditional medicine applications [15]. |

| ZINC | Commercial Compounds | Includes NPs | Contains collections of commercially available NPs for virtual screening [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Generating and Screening a Pseudo-Natural Product Library

This protocol outlines the design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of a pseudo-natural product (pseudo-NP) library to discover new bioactive chemotypes [14] [6].

1. Design and In Silico Planning

- Fragment Identification: Deconstruct known NPs into fragments according to criteria such as molecular weight (120-350 Da) and AlogP < 3.5 [14].

- Scaffold Design: Combine two or more NP fragments from different biosynthetic origins in novel connectivity patterns not observed in nature (e.g., spirocyclic, fused, bridged) to design new pseudo-NP scaffolds [14] [6].

- Cheminformatic Analysis: Calculate properties like the NP-likeness score to ensure the designed scaffolds retain the characteristic three-dimensionality and stereogenicity of NPs [6].

2. Library Synthesis

- Synthetic Strategy: Employ a build/couple/pair strategy or complexity-generating intramolecular reactions to efficiently synthesize the diverse pseudo-NP scaffolds [6].

- Characterization: Purify compounds using techniques like flash column chromatography and confirm structures using analytical methods, including ¹H NMR spectroscopy [16].

3. Biological Evaluation

- Target-Agnostic Screening: Use phenotypic assays to probe broad biological space without target bias. Recommended assays include [14] [6]:

- Glucose uptake monitoring

- Autophagy assays

- Wnt and Hedgehog signaling pathway assays

- T-cell differentiation assays

- Morphological Profiling: Implement the Cell Painting Assay to obtain a high-content morphological "fingerprint" for each compound. This can help identify novel mechanisms of action by comparing profiles to those of compounds with known targets [14].

4. Hit Validation & Target Identification

- Dose-Response Studies: Confirm activity of hit compounds using dose-response curves.

- Target Deconvolution: Use methods like chemical proteomics or drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) to identify the protein target of the bioactive pseudo-NP [6].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the pseudo-NP discovery process:

Detailed Methodology: Optimizing a Lead Compound via Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR)

This protocol is used to improve the potency and drug-like properties of an initial NP-derived hit [13].

1. Analogue Design

- Define Core Scaffold: Identify the privileged NP scaffold responsible for the biological activity.

- Plan Modifications: Systematically plan variations at different regions of the molecule (e.g., side chains, stereocenters, functional groups) to probe the SAR.

2. Library Synthesis and Profiling

- Synthesis: Synthesize the planned analogue library.

- In vitro Profiling: Test all analogues in the primary biological assay to determine potency (e.g., ICâ‚…â‚€). In parallel, assess key ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties using assays for metabolic stability, plasma protein binding, and membrane permeability [13].

3. Data Analysis and Lead Selection

- SAR Analysis: Correlate structural changes with changes in biological activity and ADMET properties to guide the next round of design.

- Select Lead Compound: Choose the compound with the best overall balance of potency, selectivity, and PK properties for further development. The optimization of isodaphnetin to a lead with a 7,400-fold potency increase is a prime example [13].

The following flowchart visualizes the SAR optimization cycle:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NP-Based Drug Discovery

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NP Fragment Libraries | Building blocks for designing pseudo-NP scaffolds or for BIOS. | Curated sets of NP-derived fragments that comply with the "rule of three" for fragments, ensuring favorable properties for library synthesis [14]. |

| Commercial NP Databases | Source of structures and metadata for dereplication and inspiration. | Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP), MarinLit. These are highly curated but require a subscription [15]. |

| Open NP Collections (e.g., COCONUT) | Source of structures for virtual screening and cheminformatic analysis. | COCONUT provides over 400,000 non-redundant NP structures for open research use [15]. |

| Screening Libraries (NP-Derived) | Collections of compounds for high-throughput screening (HTS). | Libraries based on terpenoid, polyketide, phenylpropanoid, and alkaloid scaffolds provide biologically prevalidated starting points for hit identification [13] [17]. |

| Catalysts for C-C Bond Formation | Enabling synthesis of complex NP-inspired scaffolds. | Essential for constructing the characteristic three-dimensional frameworks of NPs and their analogues (e.g., in meroterpenoid synthesis) [13]. |

| Taurolidine | Taurolidine (NMR) Powder|19388-87-5 | Taurolidine is a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent for research, derived from taurine. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Allyl 3-amino-4-methoxybenzoate | Allyl 3-amino-4-methoxybenzoate|CAS 153775-06-5 | Allyl 3-amino-4-methoxybenzoate (CAS 153775-06-5) is a benzoate ester intermediate for pharmaceutical and peptide synthesis research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Natural products (NPs) and their derivatives have been a cornerstone of pharmacotherapy for millennia, serving as a primary source of new medicines, particularly for cancer and infectious diseases [11]. Historical records, including ancient Egyptian papyri and traditional Chinese medicine texts, document the extensive use of medicinal plants, with many early isolated pure natural products like morphine, quinine, and cocaine originating from traditional remedies [18]. In the modern era, nearly half of all approved drugs between 1981 and 2019 can be traced back to unaltered NPs, derivatives, or NP-like pharmacophores, underscoring their enduring impact [19]. This technical support center leverages these historical successes to provide practical guidance for overcoming contemporary challenges in natural product research, with a focus on improving the chemical accessibility of NP leads.

The Success Metrics of Natural Products in Drug Discovery

Quantitative Evidence of Clinical Success

Natural products demonstrate a remarkable and quantifiable advantage in the drug development pipeline. While they constitute a minority of early-stage patent applications (approximately 8% of patent compounds), their success rate increases steadily through clinical trial phases [19]. This trend suggests that NPs possess inherent properties, such as superior drug-likeness and lower toxicity, that make them more likely to succeed in later, more costly stages of development.

Table 1: Proportion of Natural Products, Hybrids, and Synthetics Across Drug Development Stages

| Development Stage | Natural Products | Hybrid Compounds | Synthetic Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patent Applications | ~8% | ~15% | ~77% |

| Clinical Trial Phase I | ~20% | ~15% | ~65% |

| Clinical Trial Phase III | ~26% | ~19% | ~55.5% |

| FDA Approved Drugs | ~25% | ~20% | ~25% (Purely synthetic) |

Data sourced from analysis of over 1 million patent applications and clinical trial data [19].

Structural Classes with High Success Rates

Analysis of NP structural classes that successfully progress from Phase I trials to approval reveals specific scaffolds that are enriched in approved drugs. Terpenoids show a notable 20% relative increase, while fatty acids and alkaloids demonstrate increases of 7% and 6%, respectively [19]. Among NP superclasses, β-lactams and peptide alkaloids are significantly enriched, indicating these classes exhibit lower failure rates and represent privileged structures for drug discovery [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Research Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for NP-Based Drug Discovery

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Assays | Rapid phenotypic or target-based screening of complex NP extracts or pure compounds [11]. | Enables processing of large compound libraries; can be combined with robotic separation. |

| Advanced Analytical Tools (e.g., LC-HRMS) | Separation, dereplication, and characterization of NPs from complex mixtures [11] [1]. | Hyphenated techniques like LC-HRMS-NMR are crucial for identifying novel scaffolds. |

| In Silico Prediction Tools (e.g., NatGen) | Predicts 3D structures and chiral configurations of NPs, a major bottleneck in NP research [20]. | Achieves high accuracy (e.g., 96.87% on benchmarks); vital for NPs with unresolved stereochemistry. |

| NP Databases (e.g., COCONUT, ChEMBL) | Provide curated structural and bioactivity data for virtual screening and machine learning [1] [20]. | Essential for cheminformatics; quality and curation of data are critical. |

| ADMET In Silico Prediction Tools | Early computational prediction of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity profiles [1]. | Helps prioritize compounds with favorable drug-like properties, reducing late-stage attrition. |

| Difethialone | Difethialone, CAS:104653-34-1, MF:C31H23BrO2S, MW:539.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dimethyl malonate | Dimethyl malonate, CAS:108-59-8, MF:C5H8O4, MW:132.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs for NP Research

FAQs on Foundational Concepts

Q1: Why invest in natural products given the dominance of synthetic compounds in early patents? Despite synthetic compounds overwhelmingly outnumbering NPs in patent applications (approx. 77% vs. 23% for NPs and hybrids combined), the success rate of NPs in clinical trials is significantly higher [19]. The proportion of NP and hybrid compounds increases steadily from Phase I (approx. 35%) to Phase III (approx. 45%), with an inverse trend observed for synthetics [19]. This higher "survival rate" is likely due to evolutionary pre-optimization for biological relevance, superior drug-like properties, and lower toxicity.

Q2: What level of bioactivity should be considered promising for an NP extract or compound? Potency must be considered alongside other factors like toxicity, selectivity, and structural complexity. For initial screening in areas like insecticide development, an extract with an LC50 of approximately 100 ppm is a good starting point, while pure compounds with an LC50 ≤ 10 ppm are strong candidates for prototype development [3]. Activity at low concentrations is advantageous, but a compound with moderate potency and an excellent safety profile or novel mechanism should not be discounted.

Q3: What are the major reasons for the high attrition rate of drug candidates, and how do NPs address this? The vast majority of clinical candidates fail due to a lack of clinical efficacy and/or unmanageable toxicity [19]. NPs address these issues by often possessing inherently validated biological functions through evolutionary pressure. They frequently feature molecular scaffolds that are selective for cellular targets and have desirable ADME properties [19]. In vitro and in silico studies consistently show that NPs and their derivatives tend to be less toxic than synthetic counterparts, directly addressing a major cause of clinical failure [19].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Difficulty in identifying and isolating the specific bioactive compound from a complex natural extract.

- Solution: Implement an integrated workflow combining advanced analytical and computational techniques.

- Step 1: Employ High-Resolution Metabolomics. Use techniques like Ultra High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography coupled to tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-HRMS/MS) to rapidly separate and acquire comprehensive metabolic profiles of crude extracts [11].

- Step 2: Apply Dereplication Strategies. Use HRMS data to search in silico databases (e.g., GNPS, COCONUT) to quickly identify known compounds and avoid re-isolating common metabolites [11] [1]. This is a crucial step to prioritize novel leads.

- Step 3: Utilize Advanced NMR and Micro-Scale Isolation. For novel compounds, combine HPLC-SPE-NMR (Solid Phase Extraction-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) for structural elucidation with minimal material [11]. Micro-fractionation of the extract and linking fractions to bioactivity can pinpoint the active constituent.

Challenge 2: The 3D structure, particularly chiral configuration, of a natural product is unknown, hindering mechanistic and docking studies.

- Solution: Leverage modern deep learning frameworks for 3D structure prediction.

- Protocol: Use tools like NatGen, a deep learning framework specifically designed for predicting the chiral configurations and 3D conformations of natural products [20].

- Workflow: Input the 2D molecular structure. NatGen uses structure augmentation and generative modeling to predict the most likely chiral configuration and low-energy 3D conformation.

- Validation: This method has demonstrated high accuracy (96.87% on benchmark datasets) and can predict structures with an atomic root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) below 1 Ã…, providing reliable models for in silico studies [20]. Pre-computed structures for over 600,000 NPs are available in public databases.

Challenge 3: An active NP is not available from commercial suppliers, and re-isolation from the natural source is impractical or unsustainable.

- Solution: Develop a multi-pronged sourcing strategy early in the discovery process.

- Option 1: Synthetic Biology. Identify the biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) responsible for the NP's production. Use metabolic engineering in a heterologous host (e.g., yeast, bacteria) to produce the compound, which also helps with sustainable scale-up [11].

- Option 2: (Semi)Synthesis. If the structure is known and not overly complex, design a total or partial synthetic route. Use the NP as a starting point for generating a focused library of semi-synthetic analogues to explore structure-activity relationships (SAR) and potentially improve properties [11] [1].

- Option 3: Cultivation and Agro-technology. Investigate the possibility of cultivating the source organism. For plants, explore agro-technology and plant biotechnology to produce the natural medical compounds, transforming plants into "factories" [18].

Challenge 4: Translating in silico NP hits into experimentally validated leads due to sourcing and testing bottlenecks.

- Solution: Establish a rigorous, automated workflow for experimental validation.

- Step 1: Digital Design. Use experimental design notebooks (e.g., Jupyter notebooks with Python packages like

datarail) to systematically plan the drug response experiment. This includes specifying cell types, drugs, dose ranges, and plate layouts in a machine-readable, error-free format [21]. - Step 2: Robotic Execution. Use the digital design to guide robotic liquid handlers (e.g., HP D300 dispenser) for highly accurate and reproducible compound dispensing in multi-well plates [21].

- Step 3: Automated Data Processing. Merge raw data from high-throughput scanners (e.g., Perkin Elmer Operetta) with the treatment metadata from the digital design. Use analysis packages (e.g.,

gr50_tools) to normalize data and calculate robust sensitivity metrics like IC50 or GR50, which corrects for effects of cell division rate [21].

- Step 1: Digital Design. Use experimental design notebooks (e.g., Jupyter notebooks with Python packages like

Diagram 1: NP Bioactive Compound Identification Workflow

Diagram 2: In-silico Hit Validation Pipeline

The historical success of natural products as drugs is not serendipitous but is rooted in their evolutionary optimization for biological interaction and their vast, untapped chemical diversity. The case studies of drugs like artemisinin, paclitaxel, and morphine provide a clear roadmap for future discovery. By systematically addressing the key bottlenecks of NP research—such as compound identification, structural elucidation, and sustainable supply—with modern technological solutions like AI-based structure prediction, automated screening platforms, and synthetic biology, researchers can significantly improve the chemical accessibility of natural product leads. Integrating these advanced methodologies into a rational, data-driven workflow will ensure that natural products continue to be a vital source of innovative therapeutics for unmet medical needs.

From Complex to Feasible: Computational and Experimental Optimization Toolkits

Core Concepts and FAQs

What is the primary goal of functional group manipulation in natural product research?

The primary goal is to improve the "druggability" of natural product leads. This involves modifying their chemical structure to enhance desirable properties such as potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetics (like solubility and metabolic stability), while reducing toxicity. These modifications are essential for transforming a naturally occurring lead compound into a viable drug candidate [22] [23].

Why is the location of a functional group, such as a carbonyl, so critical?

The location of a functional group on the molecular scaffold is highly influential to its biological activity [24]. A change in position can significantly alter how the molecule interacts with its biological target (e.g., a protein or enzyme), thereby affecting the drug's efficacy and specificity.

What are common synthetic challenges when manipulating complex natural products?

A major challenge is that traditional methods for moving functional groups often require multiple synthetic steps (five or more). This lengthy process is inefficient and can be complicated by unwanted side reactions, which reduce yield and create purification difficulties [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

How can I improve the efficiency of carbonyl group transposition?

Problem: Traditional carbonyl transposition is a multi-step, inefficient process. Solution: Implement a modern, triflate-mediated α-amination strategy. This approach uses two cooperative catalysts to enable a direct, selective 1,2-transposition of the carbonyl group, reducing the required steps to just one or two. This method minimizes unwanted side reactions and offers superior control over the final position of the carbonyl [24].

How can I maintain structural complexity while improving drug-like properties?

Problem:Complex natural product scaffolds often have poor solubility or bioavailability. Solution: Focus on semi-synthesis. Use the complex natural product as a core scaffold and perform targeted functional group manipulations. This preserves the beneficial structural complexity while allowing you to fine-tune specific properties. Key transformations include:

- Reduction of alkenes to improve metabolic stability.

- Conversion of alcohols to esters or ethers to modulate lipophilicity.

- Synthesis of amides from carboxylic acids to explore new binding interactions [25] [26].

What if my natural product extract shows promising activity but isolation of the active compound fails?

Problem: Bioactivity is lost during the fractionation and isolation process. Solution: Employ a rigorous bioactivity-guided fractionation protocol [23]. After each separation step (e.g., chromatography), test all fractions for the desired biological activity. Only proceed with fractions that retain activity. This ensures the active component is not discarded and helps identify the specific compound responsible for the effect.

Quantitative Data on Natural Product-Derived Drugs

Table 1: Contribution of Natural Products to New Drug Approvals (1981-2014) [23]

| Category of Drug | Percentage of Total Approved Drugs | Example Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Pure Natural Products | 4% | Morphine, Paclitaxel |

| Natural Product-Derived | 21% | Semisynthetic antibiotics, Simvastatin |

| Synthetic drugs based on natural pharmacophores | 4% | Aspirin (from salicin) |

| Herbal Mixtures | 9.1% | - |

| Mosapride citrate dihydrate | Mosapride Citrate Dihydrate | Selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist for GI motility research. Mosapride citrate dihydrate is of high purity. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| okadaic acid ammonium salt | okadaic acid ammonium salt, CAS:155716-06-6, MF:C44H71NO13, MW:822.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Table 2: Success Rates and Challenges in Natural Product Drug Discovery [27] [23]

| Parameter | Finding/Statistic | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|

| Historical Success | 28% of NCEs (1981-2002) were natural-derived [23] | Validates the strategy of using natural products as leads. |

| Current Industry Trend | Many large pharma companies reduced NP R&D [27] | Highlights perceived challenges like supply and complexity. |

| Reported Hit Rate | Industry perceives higher HTS hit rates with NPs than academia [27] | Suggests advanced infrastructure improves success. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Carbonyl 1,2-Transposition

Title: Simplified Carbonyl Transposition via Triflate-Mediated α-Amination [24]

Objective: To relocate a carbonyl group to an adjacent carbon atom in a single, efficient step.

Materials:

- Substrate ketone

- Amination reagent (e.g., O-benzoylhydroxylamine)

- Palladium catalyst (e.g., Pd(II) salt)

- Chiral phosphoramidite ligand

- Triflic anhydride (Tfâ‚‚O)

- Base (e.g., 2,6-di-tert-butylpyridine)

- Reducing agent (e.g., triethylsilane)

- Anhydrous solvents (dichloromethane, tetrahydrofuran)

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Charge an oven-dried flask with the ketone substrate, Pd catalyst, and ligand under an inert atmosphere.

- Amination Step: Add the O-benzoylhydroxylamine reagent dropwise. Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature and monitor by TLC until the α-aminated intermediate is formed.

- Triflation: Cool the reaction to 0°C. Add a solution of triflic anhydride in DCM slowly, followed by the base. Allow the reaction to warm to room temperature and stir to form the vinyl triflate intermediate.

- Reduction: Introduce triethylsilane into the reaction flask. Heat the mixture to 40-50°C to facilitate the reduction step, which yields the transposed ketone product.

- Work-up and Purification: Quench the reaction with a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate. Extract the aqueous layer with DCM, dry the combined organic layers over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure. Purify the crude product using flash column chromatography.

Key Consideration: This method is notable for its mild reaction conditions and excellent selectivity, avoiding the extensive protecting group manipulation typically required in traditional sequences.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Functional Group Manipulation

| Reagent/Catalyst | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium Catalysts | Facilitates cross-coupling and amination reactions. | Key component in the triflate-mediated transposition cascade [24]. |

| Triflic Anhydride (Tfâ‚‚O) | Powerful electrophile for introducing the triflate leaving group. | Generates the vinyl triflate intermediate during carbonyl transposition [24]. |

| O-benzoylhydroxylamines | Serve as electrophilic amination reagents. | Used to install the initial nitrogen-containing group in the α-amination step [24]. |

| Silane Reductants (e.g., Et₃SiH) | Hydride source for reduction reactions. | Final reduction step to complete the carbonyl transposition [24]. |

| Chiral Ligands | Induce asymmetry in catalytic reactions to create single enantiomer products. | Critical for achieving stereoselectivity in the Pd-catalyzed amination step [24]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram Title: Carbonyl 1,2-Transposition Workflow

Diagram Title: Natural Product Lead Optimization Pathway

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the primary goal of SAR-directed optimization for natural products? SAR-directed optimization aims to systematically modify a natural product lead compound to enhance its drug-like properties. The process involves making structural changes and analyzing how these changes affect biological activity to establish a clear relationship between chemical structure and pharmacological effect [9]. The strategy not only addresses drug efficacy but also aims to improve ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiles and chemical accessibility associated with natural leads [9].

How does SAR-directed optimization fit into the broader drug discovery workflow? SAR-directed optimization typically occurs after the identification of a bioactive natural product lead (hit) and before preclinical development. It serves as a critical bridge where promising compounds are systematically improved through iterative design, synthesis, and testing cycles. This process transforms a natural product with initial activity into a optimized lead compound with desired potency, selectivity, and pharmacological properties [28].

SAR Methodologies and Experimental Design

What are the key methodological approaches for establishing SAR? Researchers employ multiple complementary approaches to establish meaningful SAR:

- Direct Chemical Manipulation: Systematic modification of functional groups, derivation or substitution of functional groups, alteration of ring systems, and isosteric replacement [9].

- SAR Table Analysis: Compounds, their physical properties, and activities are compiled in table format. Experts review these tables by sorting, graphing, and scanning structural features to identify relationships [29].

- Build-up Library Strategy: A modern approach that divides natural products into core and accessory fragments, then systematically recombines them to rapidly generate analog libraries for biological evaluation [30].

What is the difference between traditional SAR and the newer C-SAR approach? Traditional SAR studies are typically conducted on a single parent chemical structure, while Cross-Structure-Activity Relationship (C-SAR) analyzes pharmacophoric substituents across diverse chemotypes. C-SAR facilitates SAR expansion to any chemotype requiring modification based on existing knowledge of various compounds targeting the same biological entity, thus accelerating structural development [31].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

How can we navigate complex activity landscapes effectively? Activity landscapes can be highly variable, containing both smooth regions where gradual structural changes cause moderate activity shifts, and "activity cliffs" where minimal modifications substantially influence biological effects [32]. To address this:

- Utilize Structure-Activity Similarity (SAS) maps for graphical representation of compound distributions on activity landscapes [32].

- Implement systematic SAR analysis tools that relate compound potency and similarity to categorize different types of SARs [32].

- Employ matched molecular pair (MMP) analysis to identify critical structural changes that dramatically affect activity [31].

What strategies address the synthetic challenges of natural product optimization? Natural products often present synthetic intractability and limited availability. Several specialized strategies have been developed:

- Function-Oriented Synthesis (FOS): Focuses on synthesizing simplified analogs that retain the function of the natural product [33].

- Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS): Uses natural products as "privileged" structures to design focused libraries with higher probability of bioactivity [33].

- Two-Phase Synthesis and Analog-Oriented Synthesis (AOS): Strategies that balance synthetic efficiency with gaining SAR data [33].

- Build-up Library Approach: Enables comprehensive analog synthesis through fragment ligation, significantly accelerating structural optimization [30].

How can we separate desired target activity from undesired off-target effects? The case study of harmine optimization provides specific guidance. Harmine is a potent DYRK1A inhibitor but suffers from undesired potent inhibition of MAO-A [34]. Through systematic SAR studies involving over 60 analogues, researchers identified that:

- Small polar substituents at N-9 preserve DYRK1A inhibition while eliminating MAO-A inhibition.

- Beneficial residues at C-1 (methyl or chlorine) further enhance selectivity.

- The optimized compound AnnH75 remains a potent DYRK1A inhibitor while being devoid of MAO-A inhibition [34].

Case Study: MraY Inhibitors Optimization

Experimental Protocol: Build-up Library Construction and Evaluation

- Objective: Simultaneously optimize multiple MraY inhibitory natural products to develop new antibacterial drug leads [30].

- Library Design: Natural products were divided into core fragments (containing essential uridine moiety for MraY binding) and accessory fragments (modulating binding affinity and disposition properties) [30].

- Ligation Chemistry: Hydrazone formation between aldehyde cores and hydrazine accessories was selected due to high chemoselectivity, near quantitative yield, and only H2O as by-product [30].

- Library Assembly: 7 core aldehydes and 98 hydrazine accessories were combined to create a 686-compound library in 96-well plates [30].

- Biological Evaluation: The library was directly tested for MraY inhibitory activity and antibacterial activity without purification, identifying promising analogs with potent and broad-spectrum activity against drug-resistant strains [30].

Diagram Title: MraY Inhibitor Build-up Library Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for SAR Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in SAR Studies | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Aldehyde Core Fragments | Provide conserved binding motif for target interaction | MraY inhibitors containing essential uridine moiety [30] |

| Hydrazine Accessory Fragments | Introduce structural diversity to modulate properties | 98 fragments including benzoyl-type, phenyl acetyl-type, and lipid amino acid variants [30] |

| Matched Molecular Pairs (MMPs) | Enable identification of critical structural changes | Pairs of compounds differing only by specific structural features for C-SAR analysis [31] |

| Selective HDAC6 Inhibitors | Tool compounds for target-specific SAR development | Dataset for C-SAR approach validation [31] |

| β-Carboline Scaffolds | Core structure for kinase inhibitor optimization | Harmine analogs for DYRK1A inhibitor development with reduced MAO-A inhibition [34] |

Advanced Techniques and Data Interpretation

How do we interpret complex activity landscapes? Activity landscapes can be categorized into three main types:

- Continuous SARs: Characterized by smooth landscapes where similar structures exhibit similar potency [32].

- Discontinuous SARs: Feature "activity cliffs" where small structural changes lead to large potency changes [32].

- Heterogeneous SARs: Contain both continuous and discontinuous regions, requiring careful navigation [32].

What computational approaches support modern SAR studies?

- Molecular Docking Studies: Used to understand binding modes and interaction patterns [31].

- Binding Free Energy Calculations: Provide quantitative assessment of molecular interactions [34].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Offer insights into dynamic binding behavior and conformational changes [34].

- C-SAR Analysis: Enables extraction of SAR data from diverse chemotypes with various parent structures [31].

Table: Comparison of SAR Strategies for Natural Product Optimization

| Strategy | Key Approach | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional SAR | Sequential modification of parent structure | Established methodology, clear structure-progression | Limited to single chemotype, synthetic challenges [9] |

| C-SAR | Cross-analysis of pharmacophores across diverse chemotypes | Accelerates structural development, applicable to various chemotypes [31] | Requires diverse dataset, potential contradictory data between chemotypes [31] |

| Build-up Library | Fragment ligation with in situ screening | Rapid library generation, minimal purification, direct biological evaluation [30] | Dependent on efficient ligation chemistry, potential stability issues with products [30] |

| BIOS | Library design based on privileged natural product scaffolds | Higher probability of bioactivity, requires fewer compounds [33] | Limited structural diversity, focused on known bioactive scaffolds [33] |

Diagram Title: SAR Strategy Comparison for Natural Product Optimization

## Troubleshooting Guides

### Issue 1: Generated Compounds Have Poor Synthetic Accessibility

Problem: Molecules proposed by scaffold-hopping tools are structurally novel but appear difficult or impractical to synthesize in a laboratory setting.

Solutions:

- Leverage Synthesis-Validated Scaffold Libraries: Use tools with access to curated, synthesis-validated fragment libraries. For example, the ChemBounce framework utilizes a scaffold library derived from the ChEMBL database, which contains over 3 million unique, synthesis-validated fragments, inherently improving the practical synthetic viability of generated compounds [35].

- Consult Synthetic Accessibility Scores: Employ platforms that provide Synthetic Accessibility (SA) scores. During your workflow, filter or prioritize generated compounds based on these scores. ChemBounce, for instance, has been shown to generate structures with lower SAscores (indicating higher synthetic accessibility) compared to some commercial tools [35].

- Apply "Rule-Based" Filters: Implement standard drug-likeness filters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) during the post-processing stage to eliminate compounds with undesirable physicochemical properties that often correlate with synthetic complexity [35].

### Issue 2: Scaffold-Hopped Molecules Lose Biological Activity

Problem: After replacing the core scaffold, the new compound no longer effectively binds to the target or exhibits the desired biological effect.

Solutions:

- Enforce Pharmacophore and Shape Similarity: Ensure your scaffold-hopping method incorporates more than just 2D structure similarity. Use tools that apply constraints based on 3D electron shape similarity and pharmacophore feature matching. ChemBounce uses the ElectroShape method to evaluate electron shape similarity, helping to retain the bioactive conformation and volume of the original molecule [35].

- Utilize Advanced Pharmacophore Models: Adopt generative models that are explicitly guided by pharmacophore information. Tools like TransPharmer use ligand-based interpretable pharmacophore fingerprints to guide molecular generation, ensuring that new structures, even if structurally distinct, maintain the spatial arrangement of features critical for target interaction [36].

- Validate with Interaction Mapping: For structure-based approaches, verify that the new scaffold maintains key interactions with the target protein. The AI-AAM method uses amino acid interaction mapping as a descriptor, screening for compounds that preserve the interaction profile with the target's binding site, which can be a more reliable indicator of retained activity than simple structural similarity [37].

### Issue 3: Handling Invalid Molecular Inputs

Problem: The software fails to process the input molecular structure and returns a parsing or validation error.

Solutions:

- Preprocess and Validate SMILES Strings: Before submitting an input, always validate the SMILES string. Use standard cheminformatics tools to check for and correct common issues such as [35]:

- Invalid atomic symbols.

- Incorrect valence assignments.

- The presence of salts or multiple components separated by a ".". Extract the primary active compound.

- Malformed syntax (e.g., unbalanced brackets, invalid ring closure numbers).

- Adhere to Software Input Specifications: Carefully review the input requirements of the specific tool. For command-line tools like ChemBounce, ensure your input file is correctly formatted and that you are using the appropriate command-line options to specify your input [35].

### Issue 4: Limited Structural Novelty in Generated Compounds

Problem: The scaffold-hopping algorithm produces molecules that are too structurally similar to the input, providing limited inspiration for novel patentable candidates.

Solutions:

- Adjust Similarity Thresholds: Lower the Tanimoto similarity threshold if the tool allows it. This will force the algorithm to search a broader and more diverse chemical space, though it may require more stringent activity retention checks [35].

- Employ Generative AI Models: Use state-of-the-art generative models designed for novelty. The TransPharmer model, for example, has a unique exploration mode that enhances scaffold hopping, producing structurally distinct compounds while maintaining pharmaceutical relevance through pharmacophoric constraints [36].

- Incorporate Custom Scaffold Libraries: Use the option to input a custom, diverse scaffold library. ChemBounce supports this via the

- -replace_scaffold_filesoption, allowing you to explore niche chemical spaces, such as those derived from natural products [35].

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between pharmacophore-oriented design and traditional scaffold hopping? A1: While both aim to identify new core structures, pharmacophore-oriented design specifically uses the 3D arrangement of features essential for biological activity (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic centers) as the primary constraint for searching and designing new molecules [38] [36]. Traditional scaffold hopping may rely more heavily on 2D topological similarity or molecular shape. The pharmacophore approach ensures that the replaced scaffold maintains the critical functional geometry for target binding, even if the underlying carbon skeleton is vastly different [38].

Q2: When should I consider using a scaffold-hopping strategy in my natural product optimization project? A2: You should consider scaffold hopping when facing one or more of these common challenges in natural product lead optimization [35] [2] [39]:

- Poor ADMET Properties: To improve metabolic stability, solubility, or reduce toxicity.

- Intellectual Property Constraints: To design around existing patents by creating novel, patentable chemical series.

- Synthetic Intractability: To replace a complex, difficult-to-synthesize natural product core with a simpler, more accessible scaffold while retaining bioactivity.

- Lead Optimization Stagnation: To escape local chemical space and explore new structural avenues when traditional analog modifications fail.

Q3: How do AI-based methods like TransPharmer improve upon earlier scaffold-hopping techniques? A3: AI-based methods like TransPharmer integrate deep learning with pharmacophore modeling, offering several key advantages [36] [40]:

- Enhanced Novelty: They are better at generating structurally novel compounds that still conform to pharmacophoric constraints, effectively bridging the novelty-bioactivity gap.

- Efficient Exploration: They can rapidly explore a much wider and more diverse chemical space than traditional database searching methods.

- Direct Bioactivity Link: By using pharmacophore features as a prompt, the model directly links the generation process to features known to be critical for bioactivity. This approach has been experimentally validated, with models like TransPharmer successfully generating new scaffolds with nanomolar potency against challenging targets like PLK1 [36].

Q4: Can you provide a specific example where scaffold hopping successfully retained potency? A4: Yes. In a study applying the AI-AAM scaffold-hopping method, the SYK inhibitor BIIB-057 was used as a reference. The method identified a structurally different compound, XC608. Experimental validation showed that both compounds exhibited very similar and high potency, with IC50 values of 3.9 nM and 3.3 nM, respectively. This demonstrates a successful scaffold hop that maintained nanomolar-level pharmacological activity against the SYK target [37].

Q5: What are the key metrics to evaluate the success of a scaffold-hopping campaign? A5: Success should be evaluated using a combination of computational and experimental metrics, summarized in the table below.

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Description and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Computational | Tanimoto Similarity | Measures 2D structural similarity; a successful hop often has lower similarity [35]. |

| Shape/Pharmacophore Similarity | Measures 3D volume and feature overlap (e.g., ElectroShape); should be high to retain activity [35]. | |

| Synthetic Accessibility (SA) Score | Predicts ease of synthesis; lower scores are more favorable [35]. | |

| Drug-Likeness (QED) | Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness; higher scores indicate more drug-like properties [35]. | |

| Experimental | Binding Affinity (IC50/Kd) | Measures potency; should be comparable to or better than the lead compound [37]. |

| Target Selectivity | Assesses activity against off-targets; a new scaffold may have a improved or different selectivity profile [37]. | |

| ADMET Profile | Evaluates absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity; the goal is improvement over the lead [39]. |

## Experimental Protocols

### Protocol 1: Implementing a Standard Scaffold-Hop Using the ChemBounce Framework

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for generating novel scaffolds from a known active compound using the ChemBounce tool [35].

1. Input Preparation

- Obtain the SMILES string of your known active compound (the "lead").

- Preprocess and validate the SMILES string to ensure it represents a single, valid molecule. Remove any salts or counterions.

2. Tool Execution

- ChemBounce is executed via the command line. A typical command structure is:

- Parameters:

-o: Specify the directory where results will be saved.-i: Path to a file containing the input SMILES string.-n: Controls the number of novel structures to generate for each identified fragment.-t: (Optional) Tanimoto similarity threshold (default 0.5). A lower value encourages greater structural diversity.

3. Output and Analysis

- ChemBounce will output a set of novel compounds in SMILES format.

- The output compounds are pre-screened based on Tanimoto and electron shape similarities to the input structure.

- Post-process the results by importing the SMILES into your preferred cheminformatics suite for further analysis, filtering based on SAscore, QED, and other desired properties.

### Protocol 2: Validating a Scaffold-Hopped Compound via a Kinase Inhibition Assay

This protocol outlines a general method for experimentally confirming that a scaffold-hopped compound retains its biological activity, based on the validation performed for the AI-AAM method [37].

1. Compound Preparation

- Obtain the pure scaffold-hopped compound for testing. The purity of the compound should be confirmed using analytical methods like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). In the cited study, a purity of 96% was acceptable for validation [37].

2. In Vitro Kinase Activity Assay

- Principle: Measure the compound's ability to inhibit the target kinase's enzymatic activity.

- Procedure:

- Incubate the target kinase with its substrate and ATP in the presence of a range of concentrations of the test compound.

- Include a positive control (a known potent inhibitor) and a negative control (no inhibitor).

- After a set reaction time, quantify the amount of phosphorylated product formed using a suitable detection method (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence).

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the inhibition percentage against the logarithm of the compound concentration.

- Fit a dose-response curve to the data to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), which quantifies compound potency. A successful scaffold hop will have an IC50 value comparable to the lead compound (e.g., single-digit nM as in the AI-AAM study) [37].

3. Selectivity Profiling

- To assess the specificity of the new compound, perform the same kinase activity assay against a panel of diverse kinases (e.g., 24 kinases).

- A compound that inhibits only the target kinase (or a very select few) is considered highly selective. Note that a new scaffold may exhibit a different selectivity profile than the original lead [37].

## Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points in a typical pharmacophore-oriented scaffold-hopping process, integrating the tools and strategies discussed.

Diagram Title: Scaffold Hopping Workflow & Decision Path

## The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for implementing pharmacophore-oriented scaffold hopping.

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| ChemBounce | Software Framework | An open-source tool for scaffold hopping that uses a curated library of synthetically accessible fragments and evaluates compounds based on Tanimoto and electron shape similarity [35]. |

| TransPharmer | AI Generative Model | A generative model that integrates interpretable pharmacophore fingerprints with a GPT framework for de novo molecule generation and scaffold elaboration, excelling at producing structurally novel, bioactive ligands [36]. |

| ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) | Software Tool | A standard tool for 3D shape-based molecular comparison and virtual screening that checks for optimal shape overlap and matching of pharmacophoric features [38]. |

| ElectroShape | Algorithm/Descriptor | A method for calculating molecular similarity based on both 3D shape and charge distribution, implemented in tools like ChemBounce to better preserve biological activity during hopping [35]. |

| ChEMBL Database | Database | A large, open-scale bioactivity database. Used to build curated, synthesis-validated scaffold libraries that underpin tools like ChemBounce [35]. |

| ErG Fingerprints | Molecular Descriptor | A type of pharmacophoric fingerprint used to measure pharmacophoric similarity between molecules, demonstrating potential for scaffold hopping applications [36]. |

| 3-Methyl-5-oxohexanal | 3-Methyl-5-oxohexanal, CAS:146430-52-6, MF:C7H12O2, MW:128.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Nitroxynil | Nitroxynil, CAS:1689-89-0, MF:C7H3IN2O3, MW:290.01 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using a physics-based docking method like RosettaVS over deep learning approaches for virtual screening when the binding site is known?

A1: In scenarios where the binding site is known, physics-based ligand docking methods, such as the RosettaVS protocol, have been shown to continue to outperform deep learning models [41]. While deep learning methods are better suited for blind docking problems and offer significantly reduced computation times, physics-based methods provide greater generalizability to unseen protein-ligand complexes and can more accurately model receptor flexibility, including side chains and limited backbone movement, which is critical for many targets [41].