AI-Powered Network Pharmacology: Revolutionizing Natural Product Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and network pharmacology in natural product research.

AI-Powered Network Pharmacology: Revolutionizing Natural Product Drug Discovery

Abstract

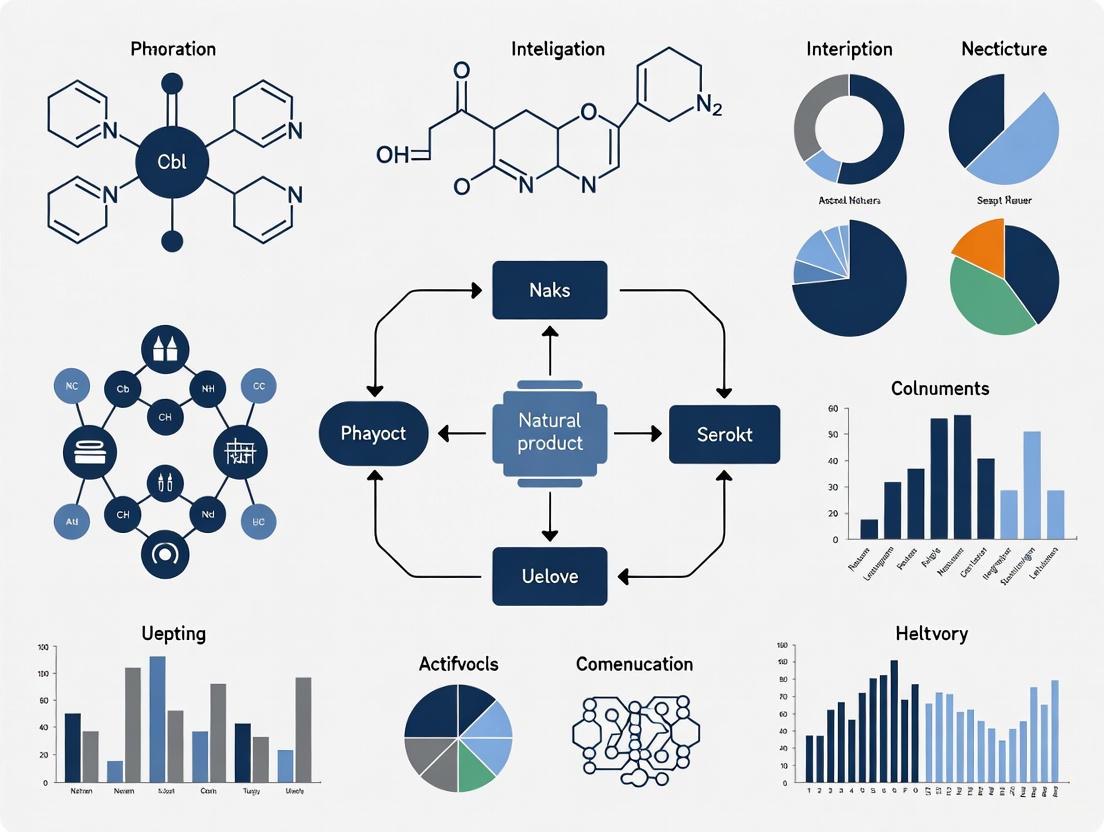

This article explores the transformative convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and network pharmacology in natural product research. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how this synergy is shifting the paradigm from a traditional 'one drug, one target' model to a systems-level, multi-target approach. The content covers the foundational principles of analyzing complex biological networks, methodological advances in AI-driven prediction and discovery, strategies to overcome key implementation challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks integrating multi-omics data. By synthesizing these aspects, the article provides a comprehensive roadmap for leveraging these technologies to decode the mechanisms of traditional medicines, accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutics, and advance personalized, precision medicine.

From Single Targets to Complex Networks: The New Paradigm in Drug Discovery

Network pharmacology represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving from the conventional "one drug–one target" model to a systems-level approach that embraces polypharmacology. This framework analyzes drug actions through the lens of biological networks, recognizing that most effective therapeutics act through modulation of multiple proteins and pathways rather than single targets. By integrating computational biology, multi-omics technologies, and artificial intelligence, network pharmacology provides powerful methodologies for deciphering complex mechanisms of multi-target drugs, particularly natural products and traditional medicines. This article presents core protocols, analytical frameworks, and applications that define this transformative discipline.

The dominant paradigm in drug discovery has historically been the concept of designing maximally selective ligands to act on individual drug targets [1]. However, this reductionist approach has faced significant challenges, as many effective drugs act via modulation of multiple proteins rather than single targets. Advances in systems biology reveal a phenotypic robustness and network structure that strongly suggests exquisitely selective compounds may exhibit lower clinical efficacy than desired compared with multitarget drugs [1].

Network pharmacology has emerged as the next paradigm in drug discovery, integrating network biology and polypharmacology to expand the opportunity space for druggable targets [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for studying traditional medicine systems, natural products, and complex drug combinations whose therapeutic effects emerge from multi-compound, multi-target interactions [2] [3]. The methodology aligns perfectly with the holistic philosophy of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), where formulations are designed to target multiple pathways simultaneously to achieve therapeutic benefits [2].

Core Principles and Definitions

Fundamental Concepts

- Polypharmacology: The principle that single drugs or drug combinations can interact with multiple molecular targets simultaneously, often producing enhanced therapeutic effects through systems-level modulation.

- Network Target: A key concept in network pharmacology where disease phenotypes and drugs act on the same biological network, pathway, or target set, affecting the balance of network targets and interfering with disease phenotypes at multiple levels [4].

- Biological Network: The interconnected system of biomolecules (proteins, genes, metabolites) and their interactions that underlie cellular functions and disease processes.

The Shift from Reductionist to Network Thinking

The transition from conventional to network-based drug discovery represents a fundamental shift in perspective [1] [2]:

Table: Paradigm Shift in Drug Discovery

| Aspect | Conventional Pharmacology | Network Pharmacology |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | One drug–one target–one disease | Multi-target, multi-component therapeutics |

| System View | Reductionist dissection | Holistic, systems biology approach |

| Therapeutic Strategy | Maximal target selectivity | Controlled polypharmacology |

| Drug Design | Single-structure optimization | Multi-structure activity relationships |

| Efficacy Model | High affinity to single target | Network perturbation and balance |

Essential Research Protocols in Network Pharmacology

Protocol 1: Core Network Pharmacology Workflow

This foundational protocol outlines the standard workflow for network pharmacology analysis, particularly applicable to natural products and traditional medicine formulations.

Materials and Reagents

- Computational Resources: Workstation with minimum 8GB RAM, multi-core processor

- Software Tools: Cytoscape (v3.8.0+), R statistical software with appropriate packages

- Database Access: TCMSP, PubChem, SwissTargetPrediction, GeneCards, STRING, KEGG

Procedure

Bioactive Compound Identification

- Retrieve chemical constituents from relevant databases (TCMSP, PubChem)

- Apply absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) screening filters

- Use standardized criteria: Oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30% and drug-likeness (DL) ≥ 0.18 [5]

Target Prediction

- Input screened compounds to target prediction platforms (SwissTargetPrediction, TCMSP)

- Cross-reference predicted targets with experimental data where available

- Standardize target nomenclature using UniProt database

Disease Target Collection

- Retrieve disease-associated genes from OMIM, DisGeNET, GeneCards databases

- Use relevant disease keywords and maintain consistent species specification (typically Homo sapiens)

Network Construction and Analysis

- Identify compound-disease target overlaps using Venn analysis

- Construct Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks using STRING database (confidence score ≥ 0.90)

- Import to Cytoscape for network visualization and topological analysis

- Calculate network parameters (degree, betweenness, closeness centrality)

Enrichment Analysis

- Perform Gene Ontology (GO) analysis for biological processes, molecular functions, cellular components

- Conduct KEGG pathway enrichment to identify significantly perturbed pathways

- Use Metascape platform with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing

Experimental Validation

- Select key targets and pathways for in vitro or in vivo validation

- Employ molecular docking for binding affinity assessment

- Design biological experiments (Western blot, PCR, immunohistochemistry) to confirm network predictions

Protocol 2: AI-Enhanced Multi-Omics Integration

Advanced protocol integrating artificial intelligence with multi-omics data for enhanced predictive capability in natural product research [6].

Materials and Reagents

- Multi-omics Data: Transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic datasets

- AI Platforms: TensorFlow/PyTorch for deep learning, scikit-learn for traditional ML

- Specialized Tools: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), AlphaFold3 for structure prediction, Chemistry42 for molecular design

Procedure

Multi-omics Data Acquisition

- Generate or acquire transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles

- Preprocess data: normalization, batch effect correction, quality control

- Annotate features using relevant biological databases

AI-Based Target Prediction

- Implement graph neural networks to analyze component-target-disease networks

- Use AlphaFold3 for protein structure prediction and binding site analysis

- Apply natural language processing (NLP) to mine literature for target associations

Network Modeling

- Construct multi-scale networks integrating compound-target, gene regulatory, and metabolic networks

- Apply network propagation algorithms to identify key network neighborhoods

- Calculate multi-omics enrichment using pathway-centric approaches

Predictive Modeling

- Train machine learning models (random forest, SVM, neural networks) on known drug-target pairs

- Validate models using cross-validation and external test sets

- Generate predictions for novel compound-target interactions

Experimental Prioritization

- Rank candidate compounds by integrated AI-confidence scores

- Design focused experimental validation based on computational predictions

- Iterate models based on experimental feedback

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Network Pharmacology

| Category | Resource/Solution | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database Resources | TCMSP | Traditional Chinese Medicine systems pharmacology database | Screening bioactive compounds and targets [5] |

| HERB | High-throughput experiment- and reference-guided database | TCM target and disease association [4] | |

| STRING | Protein-protein interaction network construction | Building PPI networks for target analysis [5] | |

| Analytical Tools | Cytoscape | Network visualization and analysis | Visualizing compound-target-disease networks [5] |

| Metascape | Gene annotation and enrichment analysis | GO and KEGG pathway enrichment [5] | |

| Sybyl-X | Molecular docking validation | Validating compound-target interactions [5] | |

| AI/Multi-omics | Graph Neural Networks | Analyzing complex biological networks | Predicting polypharmacology profiles [6] |

| AlphaFold3 | Protein structure prediction | Molecular docking without experimental structures [6] | |

| Multi-omics Platforms | Integrative analysis of biological data | Validating network pharmacology predictions [6] |

Signaling Pathway Analysis Framework

Network pharmacology frequently identifies key signaling pathways through which multi-target interventions achieve therapeutic effects. The following diagram illustrates a representative pathway analysis for diabetic nephropathy treatment using network pharmacology approach [5].

Application Case Studies

Case Study 1: Tangshen Formula for Diabetic Nephropathy

A comprehensive study demonstrated the application of network pharmacology to elucidate the mechanism of Tangshen Formula (TSF) in treating diabetic nephropathy [5].

Experimental Protocol:

- Network Analysis: Identified 24 key targets and 149 significant pathways

- Key Targets: TP53, PTEN, AKT1, BCL2, BCL2L1, PINK-1, PARKIN, LC3B, NFE2L2

- Validation Model: db/db mouse model of diabetic nephropathy

- Dosing: Low-dose (6.79 g/kg/d) and high-dose (20.36 g/kg/d) TSF for 8 weeks

- Outcome Measures: Urine albumin-creatinine ratio, mitochondrial ultrastructure, PINK1/PARKIN pathway protein expression

Findings: Network pharmacology prediction, confirmed by experimental validation, revealed that TSF activates the PINK1/PARKIN signaling pathway, enhances mitophagy, and improves mitochondrial structure in diabetic nephropathy.

Case Study 2: Guben Xiezhuo Decoction for Renal Fibrosis

This study integrated serum pharmacochemistry with network pharmacology to identify bioactive components and mechanisms of a traditional formula against renal fibrosis [7].

Experimental Protocol:

- Component Identification: HPLC-MS analysis of serum metabolites from GBXZD-treated rats

- Network Construction: 14 active components mapped to 276 target proteins

- Key Targets Identified: SRC, EGFR, MAPK3 through PPI network analysis

- Validation: Unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) rat model and LPS-stimulated HK-2 cells

- Pathway Analysis: EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance and MAPK signaling pathways

Findings: Integrated approach identified trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid and Cuminaldehyde as key bioactive components inhibiting EGFR phosphorylation and downstream fibrotic signaling.

Quality Standards and Methodological Considerations

As network pharmacology matures, quality standards and methodological rigor become increasingly important. The first international standard "Guidelines for Evaluation Methods in Network Pharmacology" has been established to increase credibility and standardization [4]. Key considerations include:

Data Quality and Reproducibility

- Chemical Characterization: Comprehensive qualitative and quantitative analysis of phytochemical composition [2]

- Standardization: Reproducible fingerprinting and activity signatures for natural products

- Dose-Response Considerations: Account for bell-shaped and hormetic dose-response relationships

Validation Standards

- Experimental Confirmation: Essential for hypothesized mechanisms [5] [7]

- Appropriate Controls: Inclusion of positive controls and dose-ranging studies [6]

- Multiple Validation Methods: Molecular docking, in vitro assays, and in vivo models

Table: Common Screening Parameters in Network Pharmacology

| Parameter | Typical Threshold | Rationale | Database Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Bioavailability (OB) | ≥ 30% | Ensures reasonable systemic absorption | TCMSP [5] |

| Drug-likeness (DL) | ≥ 0.18 | Filters compounds with poor drug-like properties | TCMSP [5] |

| Protein Interaction Confidence | ≥ 0.90 (HIGH) | Ensures high-quality PPI data | STRING [5] |

| Significance Threshold | P < 0.05, FDR < 0.05 | Statistical significance in enrichment | GO/KEGG [5] |

Network pharmacology represents a fundamental shift in pharmacological research, providing powerful methodologies for understanding complex multi-target interventions. By integrating computational prediction with experimental validation, and increasingly leveraging artificial intelligence and multi-omics technologies, this approach offers unprecedented capabilities for deciphering the mechanisms of natural products, traditional medicines, and complex drug combinations. The protocols and frameworks presented here provide researchers with standardized methodologies to apply this transformative approach to their drug discovery and mechanistic studies, particularly in the context of natural product research and traditional medicine modernization.

The Inadequacy of the One-Drug-One-Target Model for Complex Diseases

The 'one drug–one target–one drug' paradigm has long been the cornerstone of pharmaceutical development. This approach, predicated on a simplistic reductionist perspective of human anatomy and physiology, operates on the principle that administering a single drug to modulate a specific target will revert a pathobiological state to healthy status [8]. However, the staggering complexity of human biological systems—comprising an estimated ~37.2 trillion cells, ~20,000 gene-coded proteins, and ~40,000 metabolites—renders this model insufficient for addressing multifactorial diseases [8]. Complex disorders such as neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and chronic inflammation arise from breakdowns in robust physiological systems due to multiple genetic and environmental factors, establishing disease conditions that resist single-point perturbations [9]. The limitations of this outdated paradigm have catalyzed a fundamental rethinking of therapeutic drug design toward network-based approaches and multi-target strategies that align with the true complexity of human pathobiology.

Table 1: Key Limitations of the One-Drug-One-Target Paradigm

| Limitation Area | Specific Challenge | Impact on Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Complexity | Disease resilience to single-point perturbations; redundant functions and compensatory mechanisms [9] | Poor correlation between in vitro drug effects and in vivo efficacy [9] |

| Drug Effectiveness | Variable patient responses across different disease indications [8] | Low response rates: Alzheimer's (30%), arthritis (50%), diabetes (57%), asthma (60%) [8] |

| Therapeutic Resistance | Intrinsic or induced variability in drug response; target modifications [9] | One-third of epilepsy patients suffer from refractory epilepsy despite available treatments [9] |

| Development Metrics | High attrition rates throughout clinical development phases [8] | Failure rates: Phase I (46%), Phase II (66%), Phase III (30%); ~8% success rate from lead to market [8] |

Quantitative Evidence: Documenting the Paradigm's Shortcomings

The inadequacy of the single-target approach is quantitatively demonstrated through both clinical effectiveness data and pharmacological studies. Most drugs developed under this paradigm demonstrate disappointing response rates across major disease categories, with oncology patients showing the lowest positive response to conventional chemotherapy at just 25% [8]. This limited effectiveness stems from an inability to address the network nature of disease pathogenesis, where multiple pathways and targets contribute to disease establishment and maintenance [10].

The economic and temporal costs of maintaining this flawed paradigm are substantial, with the current drug discovery process requiring 12-15 years and approximately $2.87 billion to bring a new drug to market [8]. Furthermore, post-market surveillance frequently reveals safety concerns, with the FDA recalling 26 drugs from the US market between 1994-2015 primarily due to safety problems [8]. These quantitative metrics underscore the fundamental mismatch between the single-target model and the polypharmacological reality of drug action, where the average drug interacts with an estimated 6-28 off-target moieties [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Drug Effectiveness Across Disease Areas

| Drug Class/Disease Area | Patient Responders | Non-Responders | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cox-2 Inhibitors | 80% | 20% | Highest percentage of patient responders [8] |

| Asthma Medications | 60% | 40% | Significant portion of patients unresponsive to therapy [8] |

| Diabetes Treatments | 57% | 43% | Nearly half of patients lack adequate response [8] |

| Arthritis Therapies | 50% | 50% | Half of treated patients do not respond sufficiently [8] |

| Alzheimer's Treatments | 30% | 70% | Majority of patients show limited therapeutic benefit [8] |

| Cancer Chemotherapy | 25% | 75% | Lowest response rate among major disease categories [8] |

Network Pharmacology: A Systems-Based Alternative

Network pharmacology represents a fundamental shift from the single-target paradigm to a systems-level approach that redefines disease and its treatment from descriptive, symptomatic phenotypes to causative molecular mechanisms, or endotypes [10]. This approach leverages the concept that diseases result from interactions of various disease signaling networks rather than isolated pathway dysfunctions [10]. The therapeutic strategy accordingly evolves from single-target inhibition to multi-target modulation that addresses network robustness and resilience.

The advantages of multi-target agents are particularly evident in complex disorders. First, they enable simultaneous modulation of multiple targets, offering potential benefits in treating complex diseases of multifactorial etiology [9]. Second, they present advantages for health conditions linked to drug-resistance issues, as it is less probable for pathogens or disease cells to develop resistance through single-point mutations against multi-target agents [9]. Third, they offer improved pharmacokinetic profiles and better patient compliance compared to combination therapies involving multiple drugs with different pharmacokinetic properties [9] [10].

Experimental Protocols for Network Pharmacology Research

Protocol 1: Target-Based Network Identification and Validation

Objective: To identify crucial genomic, transcriptomic, or proteomic alterations in disease networks and validate multi-target drug candidates that selectively revert these network changes.

Materials and Reagents:

- Human iPSCs: Generate disease-relevant cell types (neurons, astrocytes, microglia) for physiologically relevant assay systems [10].

- High-content imaging system: For multi-parameter analysis of disease-specific biomarkers, cellular dysfunction, and pathophysiological characteristics [10].

- Omics technologies: RNA sequencing, proteomics, and metabolomics platforms for comprehensive molecular profiling [11].

- Network analysis tools: STRING database for protein-protein interactions, KEGG pathway analysis, and specialized resources like the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP) [12].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Differentiate human iPSCs into disease-relevant cell types (e.g., neurons for neurodegenerative disease studies) using established protocols [10].

- Multi-omics Data Collection: Extract and prepare RNA, protein, and metabolite samples from disease and control models. Perform RNA sequencing, proteomic profiling, and metabolomic analysis according to platform-specific protocols [11].

- Network Construction: Integrate omics data to reconstruct disease-associated networks using bioinformatic tools. Identify key network nodes and edges significantly altered in disease states [12].

- Computational Drug Screening: Screen compound libraries against multiple network targets using molecular docking and machine learning approaches. Prioritize compounds with predicted multi-target activity [11].

- Experimental Validation: Treat disease models with candidate multi-target compounds. Assess network normalization through high-content imaging and functional assays measuring key disease phenotypes [10].

- Data Integration: Correlate multi-target engagement with phenotypic improvements using statistical models. Validate network-level effects through pathway analysis [12].

Protocol 2: Phenotypic Screening for Multi-Target Drug Discovery

Objective: To identify molecules engaging multiple targets through phenotypic screening in physiologically relevant human in vitro models, without pre-specified molecular targets.

Materials and Reagents:

- Complex cell culture systems: 3D culture models, organ-on-a-chip technology, and triculture systems including neurons, astrocytes, and microglia derived from human iPSCs [10].

- Phenotypic readout systems: Biomarker assays for endogenous gene expression, protein aggregation, cellular viability, and inflammatory responses [10].

- Compound libraries: Natural product collections, approved drug libraries for repurposing, and synthetic compounds [11].

- High-throughput screening infrastructure: Automated liquid handling systems, multi-well plate readers, and high-content analyzers [10].

Procedure:

- Model System Development: Establish complex in vitro models that recapitulate key disease pathologies. For neurodegenerative diseases, develop triculture systems containing neurons, astrocytes, and microglia to model cell-cell interactions and neuroinflammation [10].

- Assay Optimization: Define and validate phenotypic readouts with clear links to clinical endpoints. For protein aggregation diseases, establish quantitative measures of aggregate formation and clearance [10].

- Primary Screening: Screen compound libraries against disease models in multi-well format. Include appropriate controls and quality metrics. Use high-content imaging to capture multiple phenotypic parameters simultaneously [10].

- Hit Confirmation: Retest initial hits in dose-response experiments. Confirm multi-target engagement through follow-up assays measuring activity against known disease-relevant targets [9].

- Target Deconvolution: Employ chemoproteomic, genetic (CRISPR), or computational approaches to identify molecular targets of phenotypic hits [11] [10].

- Lead Optimization: Synthesize and test analogs of confirmed hits to improve potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties while maintaining multi-target profiles [11].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Network Pharmacology

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | STRING, KEGG, TCMSP [12] | Network construction and pathway analysis | Database of known and predicted protein-protein interactions |

| AI/Machine Learning Platforms | antiSMASH [11], NPClassifier [11], Spec2Vec [11] | Natural product analysis and biosynthetic gene cluster prediction | Structural classification of natural products; MS2 spectral similarity scoring |

| Cell Models | Human iPSC-derived cells [10] | Disease modeling and phenotypic screening | Patient-specific; reproduce molecular disease mechanisms |

| Advanced Culture Systems | 3D culture models, organ-on-a-chip [10] | Physiologically relevant drug testing | Mimic tissue-level complexity and cell-cell interactions |

| Multi-omics Technologies | RNA sequencing, proteomics, metabolomics [11] | Comprehensive molecular profiling | Unbiased identification of disease networks and drug effects |

| Natural Product Resources | Traditional medicine compound libraries [13] [12] | Source of multi-target compounds | Extensive chemical diversity with evolutionary optimization for bioactivity |

The inadequacy of the one-drug-one-target model for complex diseases necessitates a fundamental paradigm shift toward network-based, multi-target therapeutic strategies. The integrated application of target-based and phenotypic approaches, supported by advanced human model systems and AI-driven computational tools, provides a robust framework for addressing disease complexity. Natural products, with their inherent bioactivity and structural diversity, represent particularly promising starting points for multi-target drug development [13] [11]. By embracing network pharmacology and abandoning the constraints of single-target thinking, researchers can develop more effective treatments that address the true complexity of human disease networks.

Biological systems are inherently complex, composed of numerous molecular entities that interact in precise ways to maintain cellular and organismal functions. A biological network is a method of representing these systems as complex sets of binary interactions or relations between various biological entities [14]. In this framework, nodes (also called vertices) represent the biological entities—such as proteins, genes, or metabolites—while edges (also called links) represent the physical, regulatory, or functional interactions between them [15] [14]. This network paradigm has fundamentally transformed how researchers conceptualize biological processes, shifting from a reductionist focus on individual components to a systems-level understanding of interconnected pathways and functions. Within the context of network pharmacology and artificial intelligence in natural product research, this approach provides the foundational framework for understanding how multi-component natural products exert their polypharmacological effects through simultaneous modulation of multiple network nodes and edges [2] [6].

Core Structural Elements of Biological Networks

Nodes: The Fundamental Units

In biological networks, nodes represent the key functional entities within the system. The identity of these nodes varies depending on the network type:

- Protein-Protein Interaction Networks: Nodes represent proteins, with highly-connected proteins (hubs) often being essential for survival [14].

- Gene Regulatory Networks: Nodes represent genes and their regulatory elements (transcription factors) [14].

- Metabolic Networks: Nodes represent small molecules (substrates and products) such as carbohydrates, lipids, or amino acids [14].

- Neuronal Networks: Nodes represent neurons or distinct brain regions [14].

The importance of individual nodes can be characterized using various mathematical measures including degree (number of connections), betweenness (influence over information flow), and centrality within the network structure [16]. In directed networks, distinction is made between in-degree (edges pointing toward a node) and out-degree (edges pointing away from a node), which is particularly relevant for regulatory networks where transcription factors (high out-degree) regulate numerous target genes [16].

Edges: The Relationships and Interactions

Edges represent the functional relationships between nodes, which can be categorized into several distinct types based on their biological nature:

- Physical Interactions: Direct physical contacts between biomolecules, such as protein-protein interactions in complex formation [15].

- Regulatory Interactions: Directed activation or inhibition events, such as transcription factor-target gene relationships [15] [14].

- Genetic Interactions: Functional relationships where combined perturbations produce unexpected phenotypes, such as synthetic lethality [15].

- Similarity Relationships: Connections based on shared attributes, such as gene co-expression patterns or protein sequence similarity [15].

In directed networks, edges have specific orientations (e.g., A → B indicates A regulates B), while in undirected networks, edges represent mutual or bidirectional relationships [14] [16]. Edge thickness or color saturation can be used to represent quantitative attributes such as interaction strength, confidence scores, or gene expression correlation [15].

Network Properties and Topology

Biological networks exhibit distinct architectural properties that influence their functional capabilities and dynamic behavior:

- Scale-free topology: Many biological networks follow a power-law degree distribution where most nodes have few connections, while a few hubs have many connections [14].

- Small-world property: Most nodes can be reached from all others through only a few interactions, facilitating efficient information flow [14].

- Modularity: Networks often contain densely connected subgroups (modules or clusters) that correspond to functional units such as protein complexes or pathways [15].

- Motifs: Recurring, significant patterns of interconnections that serve as functional building blocks, such as feed-forward loops in transcriptional networks [16].

Table 1: Key Biological Network Types and Their Components

| Network Type | Node Representation | Edge Representation | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interaction | Proteins | Physical interactions | Identifying complexes and functional modules |

| Gene Regulatory | Genes, transcription factors | Regulatory relationships | Understanding transcriptional programs |

| Metabolic | Metabolites, small molecules | Biochemical reactions | Modeling metabolic fluxes and pathways |

| Signaling | Proteins, second messengers | Signal transduction | Elucidating signaling cascades |

| Neuronal | Neurons, brain regions | Synaptic connections | Mapping information processing |

Analytical Framework: From Network Visualization to Interpretation

Network Visualization Principles

Effective network visualization is crucial for biological interpretation and hypothesis generation. The following principles guide the creation of intelligible network figures:

- Layout Optimization: Automated layout algorithms (e.g., force-directed or spring-embedded) place connected nodes near each other and reduce edge crossing, making relationships more apparent [15] [17]. For large networks (>500 nodes), consider alternative representations such as adjacency matrices or decompose into smaller functional modules [15] [17].

- Visual Feature Mapping: Node color, size, and shape can represent biological attributes such as subcellular localization, expression level, or functional classification [15]. Edge thickness and color can represent interaction strength, confidence, or correlation [15].

- Spatial Interpretation: Be mindful that spatial proximity and arrangement influence interpretation—nodes drawn near each other are perceived as functionally related, while central positioning may imply importance [17].

Core Analysis Patterns

Several recurring analytical patterns facilitate biological insight from network representations:

- Guilt-by-Association: Inferring functions for uncharacterized nodes based on the known functions of their interaction partners [15]. For example, proteins Psf1, Psf2, and Psf3 were implicated in DNA replication through their interactions with known replication fork proteins [15].

- Cluster Identification: Densely interconnected node groups often correspond to functional units such as protein complexes or pathways [15]. The Origin Recognition Complex (ORC) in yeast displays such dense interconnections [15].

- Global System Relationships: Examining connections between functional modules reveals higher-order organization [15]. For instance, analysis of the yeast chromosome maintenance network revealed that nucleosome and replication fork components are transcriptionally correlated within groups but not between them, indicating coordinated regulation at different cell cycle phases [15].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Network Edge Detection

| Interaction Type | Experimental Method | Key Features | Common Databases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein | Yeast two-hybrid, Pull-down + Mass Spectrometry | Detects binary physical interactions | BioGRID [15], MINT [14], IntAct [14] |

| Genetic Interactions | Synthetic lethality screens | Identifies functional relationships | BioGRID [14] |

| Regulatory | ChIP-seq, ChIP-chip | Maps transcription factor binding sites | ENCODE, modENCODE |

| Gene Co-expression | Microarray, RNA-seq | Measures transcriptional coordination | GEO, ArrayExpress |

Network Modulation in Pharmacology and Natural Product Research

The Network Pharmacology Paradigm

Network pharmacology represents a fundamental shift from the conventional "one-drug, one-target" model to a "network-target, multiple-component-therapeutics" approach [2]. This paradigm is particularly suited to natural product research because:

- Polypharmacology: Most drugs and natural compounds interact with multiple receptors, resulting in pleiotropic therapeutic effects through multi-target interactions [2].

- Systems-level Intervention: Complex diseases like cancer and metabolic disorders rarely result from single gene defects but rather from dysregulation of interconnected pathways [2] [6].

- Synergistic Actions: Multi-component herbal preparations can target multiple nodes within a disease network, potentially achieving enhanced therapeutic effects through synergistic actions [2].

The essence of network pharmacology is to evaluate how therapeutic interventions interact with multiple targets, their associated signaling pathways, and the resulting modulation of biological functions relevant to disease [2].

AI-Enhanced Network Analysis in Natural Product Research

Artificial intelligence, particularly graph neural networks (GNNs), has revolutionized the analysis of biological networks in natural product research through several key applications:

- Target Prediction: AI models can predict novel compound-target interactions by analyzing complex "component-target-disease" networks [6].

- Molecular Docking Optimization: AlphaFold3-predicted protein structures enhance molecular docking accuracy for natural product target identification [6].

- Multi-omics Integration: AI facilitates the integration of transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to construct dynamic "component-target-phenotype" networks [6].

A representative example includes the demonstration that the Jianpi-Yishen formula attenuates chronic kidney disease progression through betaine-mediated regulation of multiple metabolic pathways, synergistically modulating macrophage polarization dynamics [6].

Experimental Protocols for Network Analysis and Modulation

Protocol 1: Construction and Analysis of a Protein-Protein Interaction Network

Objective: Identify novel components and functional associations within a biological system of interest through protein-protein interaction network analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- BioGRID Database: Provides curated protein-protein interaction data from multiple experimental sources [15] [14].

- Cytoscape Software: Open-source platform for network visualization and analysis (Cytoscape Consortium) [17].

- Gene Ontology Database: Source of functional annotation for guilt-by-association analysis [15].

- STRING Database: Resource for predicted and experimentally validated interactions with confidence scores [14].

Procedure:

- Data Retrieval: Query BioGRID or STRING databases using a gene list relevant to your biological system (e.g., yeast chromosome maintenance proteins) [15].

- Network Construction: Import interaction data into Cytoscape, representing proteins as nodes and interactions as edges [17].

- Layout Application: Apply a force-directed layout algorithm to organize the network, then manually adjust node positions to reduce edge crossing and improve clarity [15] [17].

- Functional Annotation: Map additional data types onto the network using visual features:

- Cluster Identification: Identify densely interconnected regions using built-in clustering algorithms (e.g., MCODE) or visual inspection [15].

- Guilt-by-Association Analysis: For uncharacterized proteins, examine the functional annotations of direct interaction partners to generate hypotheses about function [15].

- Experimental Validation: Design follow-up experiments (e.g., knockout, knockdown, or localization studies) to test predictions generated from network analysis.

Troubleshooting:

- For overly dense networks ("hairballs"), apply edge filtering based on confidence scores or focus on specific functional modules [15] [17].

- When node labels cause clutter, use adjacency matrices as an alternative representation or provide an interactive online version [17].

Protocol 2: Network Pharmacology Analysis of Herbal Formulations

Objective: Systematically identify multi-component, multi-target mechanisms of action for complex natural product formulations.

Materials and Reagents:

- TCMSP Database: Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology database for compound-target relationships [6].

- GeneCards Database: Human gene database for disease-associated targets [6].

- KEGG Pathway Database: Resource for pathway enrichment analysis [6].

- AutoDock Vina: Molecular docking software for validating predicted interactions [6].

Procedure:

- Compound Identification: Compile a comprehensive list of phytochemical constituents from the herbal formulation using analytical chemistry methods (LC-MS/MS) and literature mining [6].

- Target Prediction: For each compound, predict protein targets using:

- Disease Target Compilation: Assemble a list of genes/proteins associated with the target disease from GeneCards, OMIM, and TTD databases [6].

- Network Construction: Build a "compound-target-disease" network using Cytoscape, with distinct node types for compounds, proteins, and pathways [6].

- Network Analysis: Identify key network nodes using topological parameters (degree, betweenness centrality) and enriched pathways using KEGG analysis [6].

- Molecular Docking: Validate high-priority compound-target predictions using molecular docking simulations [6].

- Experimental Validation: Test network predictions using in vitro and in vivo models, measuring effects on predicted targets and pathways [6].

Troubleshooting:

- For poorly characterized compounds, use structural similarity to well-annotated compounds for target prediction [6].

- When facing incomplete pathway annotations, integrate multiple omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics) to reconstruct context-specific networks [6].

Visualization Schematics for Network Concepts and Workflows

Network Pharmacology Workflow

Network Elements and Properties

Table 3: Essential Resources for Biological Network Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Visualization | Cytoscape [17], yEd [17] | Network layout, visualization, and analysis | General network biology, PPI analysis |

| Interaction Databases | BioGRID [15] [14], STRING [14], MINT [14] | Curated protein-protein interactions | Network construction and validation |

| Functional Annotation | Gene Ontology [15], KEGG [6] | Functional and pathway annotation | Guilt-by-association analysis, pathway mapping |

| Natural Product Resources | TCMSP [6], TCM Database @Taiwan [6] | Compound-target relationships for natural products | Network pharmacology of herbal medicines |

| Computational Analysis | Mfinder [16], FANMOD [16] | Network motif detection | Identification of functional network patterns |

| AI-Enhanced Prediction | AlphaFold3 [6], Chemistry42 [6] | Protein structure prediction and molecular design | Target identification and compound optimization |

The paradigm of drug discovery is shifting from a single-target approach to a holistic, network-based model. This transition is particularly transformative for natural product (NP) research. Natural products, with their inherent structural complexity and evolutionary optimization for biological interaction, represent ideal candidates for network pharmacology, which understands disease as a perturbation of complex intracellular and intercellular networks [2]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and advanced analytical techniques is now empowering researchers to decode the synergistic, multi-target mechanisms of NPs systematically, moving beyond serendipitous discovery to rational, data-driven investigation [18].

This Application Note details the theoretical foundation and practical methodologies for implementing network-based approaches in NP research. It provides actionable protocols for uncovering the complex mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of natural products, framed within the context of modern computational and AI-driven pharmacology.

Theoretical Foundation: The Convergence of Natural Products and Network Pharmacology

The Inherent Polypharmacology of Natural Products

The traditional "one-drug-one-target" paradigm, while successful for some therapies, has proven inadequate for treating complex, multifactorial diseases such as Alzheimer's, cancer, and metabolic syndromes. In contrast, NPs inherently engage in polypharmacology—interacting with multiple biological targets simultaneously [2]. This multi-target action often results in synergistic therapeutic effects, where the overall activity is greater than the sum of the contributions of individual constituents [2]. This principle is central to traditional medicine systems like Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), where herbal combinations are formulated so that ingredients work harmoniously to address multiple symptoms and target various organs [2].

The Network Medicine Perspective

Network pharmacology investigates drug actions within the framework of biological systems, focusing on interactions between drugs, targets, and disease-related pathways [2]. Diseases are rarely caused by a single gene or protein defect but rather arise from disturbances in complex intracellular and intercellular networks [2]. When the multi-target nature of NPs is mapped onto these disease networks, it becomes possible to understand how they can comprehensively restore biological balance, offering a scientific rationale for their efficacy in treating complex conditions [2].

Table 1: Key Advantages of Network-Based Approaches for Natural Product Research

| Advantage | Traditional Approach | Network-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Insight | Focus on single target/pathway | Holistic analysis of multi-target, system-wide effects [2] |

| Synergy Detection | Difficult to identify and quantify | Bioinformatics and network models can predict and validate synergistic interactions [2] |

| Dereplication | Time-consuming, labor-intensive | AI and molecular networking enable rapid identification of known compounds [18] [19] |

| Lead Discovery | Bioassay-guided fractionation | Data-driven prioritization of novel bioactive compounds [19] |

Essential Research Toolkit for Network-Based NP Analysis

A successful network pharmacology study of natural products relies on a suite of computational and analytical tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Category / Item | Specific Examples & Databases | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Databases | HERB, PubChem, GeneCards, DisGeNET, OMIM, TTD, UniProt [20] | Prediction of NP targets and identification of disease-associated genes. |

| Pathway Analysis Tools | DAVID, KEGG, STRING [20] | Functional enrichment analysis and protein-protein interaction (PPI) network construction. |

| AI/ML Platforms | SwissTargetPrediction, PharmMapper, InsilicoGPT [18] [20] | Target prediction, molecular property forecasting, and data extraction from literature. |

| Analytical Chemistry | LC-MS/MS, GNPS, SIRIUS, Qemistree [19] | Chemical characterization, dereplication, and metabolome profiling of NP extracts. |

| Molecular Modeling | AutoDock, PyMol, Cytoscape [20] | Molecular docking, binding affinity validation, and network visualization. |

| 2-Chloroacetamide-d4 | 2-Chloroacetamide-d4, CAS:122775-20-6, MF:C2H4ClNO, MW:97.54 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Procyanidin B2 3,3'-di-O-gallate | Procyanidin B2 3,3'-di-O-gallate, CAS:79907-44-1, MF:C44H34O20, MW:882.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Comprehensive Network Pharmacology Workflow

This protocol outlines the core computational workflow for identifying NP targets, constructing interaction networks, and elucidating mechanisms of action, as applied in studies on natural products like diosgenin for NASH [20].

Key Materials & Reagents:

- Software: Cytoscape 3.7.2, STRING database, DAVID database, molecular docking software (e.g., AutoDock Tools) [20].

- Databases: HERB, PubChem, GeneCards, DisGeNET, UniProt [20].

Procedure:

- Target Prediction: Input the NP's structure (e.g., from PubChem) into prediction databases like SwissTargetPrediction and PharmMapper to generate a list of potential protein targets [20].

- Disease Target Identification: Compile genes associated with the disease of interest (e.g., NASH) from databases like GeneCards, DisGeNET, and OMIM [20].

- Network Construction:

- Identify overlapping targets between the NP and the disease.

- Input the overlapping targets into the STRING database to build a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network. Set a minimum interaction score (e.g., >0.4) [20].

- Import the PPI network into Cytoscape for visualization and topological analysis (e.g., by degree value) to identify hub targets [20].

- Enrichment Analysis: Perform Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis on the overlapping targets using the DAVID database. Apply a threshold (e.g., FDR < 0.05) to identify significantly enriched biological processes and pathways [20].

- Molecular Docking Validation: Select hub targets and retrieve their 3D structures from the PDB. Dock the NP molecule to these targets using software like AutoDock. A binding affinity of less than -5.0 kcal/mol generally indicates good binding activity [20].

Diagram 1: Network pharmacology workflow for natural products.

Protocol 2: AI-Enhanced Identification of Novel Natural Products

This protocol leverages AI and molecular networking to efficiently discover and identify novel NPs from complex biological mixtures, overcoming traditional dereplication challenges [18] [19].

Key Materials & Reagents:

- Equipment: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system.

- Software & Platforms: Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS), SIRIUS, MolNetEnhancer [19].

- AI Tools: DEREPLICATOR+, MetaMiner, VarQuest for structural annotation [19].

Procedure:

- LC-MS/MS Data Acquisition:

- Extract the NP source (e.g., plant, fungus) and analyze using LC-MS/MS in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode.

- Convert raw data to open formats (mzXML, mzML, .MGF) using tools like MSConvert [19].

- Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN):

- Upload the processed data to the GNPS platform .

- Use the FBMN workflow to create a molecular network. Nodes represent molecules, and edges represent spectral similarities, grouping structurally related compounds into "molecular families" [19].

- AI-Powered Structural Annotation:

- Use GNPS-integrated tools like DEREPLICATOR+ to automatically annotate nodes by comparing MS2 spectra against public spectral libraries.

- For unknown compounds, use in-silico fragmentation tools like SIRIUS to predict molecular formulas and structures [19].

- Data Integration and Prioritization:

- Integrate results using MolNetEnhancer to generate chemical-class annotated networks.

- Prioritize nodes that are both unannotated (potentially novel) and clustered in regions of interest (e.g., associated with a specific bioactivity in Bioactive Molecular Networking) for targeted isolation [19].

Diagram 2: AI-enhanced molecular networking workflow.

Case Study: Pathway-Based Discovery of Alzheimer's Therapeutics

A 2025 study exemplifies the power of the network-based approach by identifying novel natural products, (-)-Vestitol and Salviolone, for Alzheimer's disease (AD) [21].

Experimental Workflow & Key Findings:

- Network Construction: Researchers built an AD-related pathway-gene network through text mining and database integration, encompassing pathways from multiple perspectives (e.g., "Most Studied Pathways," "Gene-Associated Pathways") [21].

- Product Selection & Safety: Natural products predicted to target multiple AD pathways were selected. The safety of (-)-Vestitol and Salviolone was first confirmed in C57BL/6J mice [21].

- Efficacy Validation: APP/PS1 transgenic mice (an AD model) were treated with the compounds individually and in combination. Cognitive function was assessed using behavioral tests (Morris water maze, Y-maze) [21].

- Mechanistic Elucidation: The combination therapy synergistically improved cognitive function, reduced Aβ deposition, and regulated AD-related pathways (e.g., Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, Calcium signaling) more comprehensively than either compound alone, as shown by transcriptomic analysis and qRT-PCR [21].

Table 3: Quantitative Results from the In Vivo Validation of (-)-Vestitol and Salviolone in APP/PS1 Mice [21]

| Treatment Group | Cognitive Test Performance | Aβ Deposition | Key Pathway Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Vehicle) | Baseline impairment | High levels | -- |

| (-)-Vestitol alone | Moderate improvement | Moderate reduction | Partial pathway regulation |

| Salviolone alone | Moderate improvement | Moderate reduction | Partial pathway regulation |

| Combination Therapy | Synergistic improvement | Significant reduction | Comprehensive regulation |

The integration of natural products with network pharmacology and artificial intelligence represents a powerful and rational framework for modern drug discovery. The inherent multi-target, synergistic nature of NPs makes them a perfect match for a methodology that views disease through a systems-wide lens. As the protocols and case studies herein demonstrate, researchers can now move beyond reductionist approaches to systematically decode the complex mechanisms of natural products, accelerating the discovery of novel, effective, and safe therapeutics for complex diseases. This synergy between nature's chemistry and cutting-edge computational technology is poised to redefine the future of pharmaceutical research.

Historical Context and the Evolution from Network Biology to Pharmacology

Historical Context and Core Concepts

The evolution from network biology to network pharmacology represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving away from the traditional "one drug–one target–one disease" model toward a more holistic "multiple targets, multiple effects, complex diseases" approach [22] [23]. This transition was driven by the recognition that many effective drugs act on multiple targets rather than a single one, and that complex diseases involve interactions of multiple genes and functional proteins [23].

The origins of network pharmacology can be traced to 1999 when Shao Li pioneered the concept of linking Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) syndromes with biomolecular networks [22]. The term "Network Pharmacology" was formally introduced in 2007 by Andrew L. Hopkins, who emphasized that many effective drugs act on multiple targets within biological networks [22]. The field has since experienced exponential growth, with publications increasing dramatically in recent years [22].

Network pharmacology and Traditional Chinese Medicine share a synergistic relationship, as both embrace holistic, system-level approaches to treatment [22] [23]. TCM's characteristic multi-component, multi-targeted, and integrative efficacy perfectly corresponds to network pharmacology applications, making it a natural model for studying combination therapy [22].

Key Theoretical Frameworks and Quantitative Measures

Network Proximity and Separation Metrics

A fundamental advancement in network pharmacology has been the development of quantitative measures to characterize relationships between drug targets and disease modules within the human protein-protein interactome. The separation measure (sAB) quantifies the topological relationship between two drug-target modules [24]:

sAB ≡ 〈dAB〉 - (〈dAA〉 + 〈dBB〉)/2

Where:

- 〈dAB〉 represents the mean shortest path between drug A and drug B targets

- 〈dAA〉 and 〈dBB〉 represent the mean shortest path within each drug's targets

This measure helps classify drug-drug-disease combinations into six distinct topological categories [24]:

Table 1: Classification of Drug-Drug-Disease Network Configurations

| Configuration Type | Network Relationship | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Overlapping Exposure | Two overlapping drug-target modules that also overlap with the disease module | Limited clinical efficacy |

| Complementary Exposure | Two separated drug-target modules that individually overlap with the disease module | Correlates with therapeutic effects |

| Indirect Exposure | One drug-target module of two overlapping drug-target modules overlaps with the disease module | Not statistically significant for efficacy |

| Single Exposure | One drug-target module separated from another drug-target module overlaps with the disease module | Not statistically significant for efficacy |

| Non-exposure | Two overlapping drug-target modules are topologically separated from the disease module | Not statistically significant for efficacy |

| Independent Action | Each drug-target module and disease module are topologically separated | Not statistically significant for efficacy |

Research on approved drug combinations for hypertension and cancer has demonstrated that only the Complementary Exposure class correlates strongly with therapeutic effects, where drug targets hit the disease module but target separate neighborhoods [24].

The "Network Target" Concept

The "network target" concept represents a cornerstone of network pharmacology, proposing that disease phenotypes and drugs act on the same network, pathway, or target, thus affecting the balance of network targets and interfering with phenotypes at all levels [22]. This concept aligns with TCM's holistic theory and provides a framework for understanding how multi-component therapies achieve their integrative effects.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Research Resources for Network Pharmacology Studies

| Resource Type | Name | Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCM-Related Databases | TCMSP | Chinese herbal medicine action mechanism analysis, including 499 herbs with ingredients and pharmacokinetic properties | https://tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php [25] |

| ETCM 2.0 | Comprehensive information on TCM formulas, ingredients, and predictive targets | http://www.tcmip.cn/ETCM/ [25] | |

| TCMID 2.0 | Comprehensive database with 46,929 prescriptions, 8,159 herbs, and 43,413 ingredients | https://bidd.group/TCMID/about.html [25] | |

| Disease and Gene Databases | GeneCards | Human gene database providing genomic, proteomic, and functional information | [25] |

| OMIM | Catalog of human genes and genetic disorders | [25] | |

| TTD | Therapeutic Target Database documenting known and explored therapeutic proteins | [25] | |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG | Resource for understanding high-level functions of biological systems | [25] |

| Network Visualization & Analysis | Cytoscape | Open-source platform for complex network visualization and analysis | Version 3.10.2 [25] |

| ClueGo | Cytoscape plugin for pathway analysis | [25] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Workflow for Network Pharmacology Analysis

The standard methodology for network pharmacology research involves three integrated stages [25]:

Stage 1: Network Construction

- Collect TCM compound data through analytical techniques

- Mine drug/disease targets from biological databases (TCMSP, PubChem, GeneCards, ETCM)

- Integrate known drug-target-disease relationships

- Visualize initial networks using software like Cytoscape

Stage 2: Network Analysis

- Apply network topology principles to predict pharmacological effects

- Calculate key metrics including network proximity and separation scores

- Identify critical nodes and pathways within the constructed networks

- Perform functional enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG)

Stage 3: Experimental Validation

- Conduct molecular docking to verify predicted interactions

- Perform ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) modeling

- Validate findings through in vivo/in vitro experiments

- Use appropriate controls and dose ranges for pharmacological validation

Network Pharmacology Workflow

Protocol for Predicting Efficacious Drug Combinations

Based on the network-based methodology for identifying clinically efficacious drug combinations [24]:

Step 1: Data Assembly

- Collect experimentally confirmed protein-protein interactions (PPI) from available databases

- Compile drugs with at least two experimentally reported targets from high-quality drug-target binding affinity profiles

- Define disease modules using known disease-associated proteins

Step 2: Network Proximity Calculation

- Calculate separation score (sAB) between drug pairs using the formula provided in section 2.1

- Compute network proximity between drug targets and disease modules

- Classify drug-drug-disease combinations into the six topological categories

Step 3: Combination Efficacy Assessment

- Prioritize drug pairs showing Complementary Exposure pattern (sAB ≥ 0 with both drugs hitting disease module but targeting separate neighborhoods)

- Validate predictions using known efficacious combinations for reference diseases (hypertension, cancer)

- Exclude combinations falling into other topological categories that lack statistical significance for efficacy

Step 4: Experimental Validation

- Test prioritized combinations in relevant biological assays

- Compare efficacy against monotherapies

- Assess potential toxicity profiles

Integration with Artificial Intelligence and Multi-Omics Technologies

The convergence of network pharmacology with artificial intelligence (AI) and multi-omics technologies represents the current frontier in the field [25]. This integration addresses several limitations of conventional approaches:

AI-Enhanced Network Analysis

Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has revolutionized network pharmacology by enabling predictive precision through several approaches [18] [25]:

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) analyze complex component-target-disease networks

- AlphaFold3 predicts protein structures to optimize molecular docking

- Generative AI (e.g., Chemistry42 platform) facilitates molecular design and optimization

- Natural Language Processing (NLP) algorithms analyze extensive text data from scientific literature and patents

NP-AI-Omics Integration Framework

Knowledge Graphs for Causal Inference

Recent advances involve the development of natural product science knowledge graphs that organize multimodal data (chemical structures, genomic data, assay data, spectroscopic data) into structured representations [26]. These knowledge graphs facilitate causal inference rather than mere prediction, enabling researchers to anticipate natural product chemistry in a manner that mimics human scientific reasoning [26].

The Experimental Natural Products Knowledge Graph (ENPKG) exemplifies how unstructured data can be converted to connected data, enabling the discovery of new bioactive compounds through semantic web technologies [26].

Applications in Natural Product Research

Network pharmacology has become particularly valuable in natural product research, especially for studying Traditional Chinese Medicine, where it has been applied to:

- Decipher the biological basis of TCM syndromes and diseases [22]

- Predict TCM targets and screen active compounds [22]

- Understand the complex mechanisms of herbal formulae [23]

- Develop evidence-based novel TCM prescriptions [25]

- Reduce reliance on trial-and-error approaches for bioactive compound screening [25]

This methodology has enabled researchers to bridge empirical TCM knowledge with modern mechanism-driven precision medicine, offering a sustainable approach to drug discovery from natural products [25].

AI in Action: Tools and Techniques for Predictive Pharmacology

Network pharmacology represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving away from the traditional "one-target, one-drug" model to a more holistic "multi-target drug" approach [27]. This framework is particularly suited for studying natural products and traditional medicine systems, such as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), which inherently function through multi-component, multi-target mechanisms [25] [28]. The massive, heterogeneous biological data involved in mapping these complex interactions has made artificial intelligence (AI) an indispensable tool. Machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and especially graph neural networks (GNNs) now form the technological core that enables researchers to efficiently screen bioactive compounds, identify therapeutic targets, and elucidate complex mechanisms of action from network pharmacology data [27] [29].

Table 1: Core AI Technologies in Network Pharmacology

| Technology | Key Functionality | Primary Applications in Network Pharmacology |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | Builds predictive models from data to identify patterns and relationships [30]. | Screening biologically active small molecules, target identification, metabolic pathway analysis [27]. |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Uses multi-layered neural networks to learn from vast amounts of heterogeneous data [27] [31]. | Protein-protein interaction network analysis, hub gene analysis, binding affinity prediction [27] [32]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNN) | Processes graph-structured data (nodes and edges) to learn representations of complex networks [29]. | Drug-target interaction prediction, molecular property prediction, de novo drug design [33] [29]. |

Machine Learning Foundations

Machine learning provides the foundational algorithms for analyzing structured data in network pharmacology. Supervised learning techniques, including support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), and logistic regression, are widely employed for classification and regression tasks such as predicting drug-target interactions and classifying disease states [30]. For instance, in a study on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, six different ML algorithms were utilized to identify the most characteristic gene (CEBPD) from protein-protein interaction networks, demonstrating the power of ensemble learning approaches [30].

Key Application Protocol: Target Identification Using Machine Learning

Objective: To identify potential protein targets for a given natural compound using supervised machine learning.

Materials:

- Computational Environment: RStudio or Python environment with scikit-learn.

- Software Packages:

limma(R),caret(R), orscikit-learn(Python). - Databases: ChEMBL, DrugBank, TCMSP [25] [31].

Procedure:

- Data Collection and Preprocessing: Assemble a known set of compound-target interactions from databases like ChEMBL [28] or TCMSP [25]. Compute molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, lipophilicity) for each compound and encode protein sequences.

- Feature Engineering: Select the most informative molecular and protein features using methods like recursive feature elimination or principal component analysis.

- Model Training and Validation: Split the data into training (70-80%) and testing (20-30%) sets. Train multiple classifier models (e.g., SVM, RF) on the training set. Optimize hyperparameters via cross-validation and evaluate performance on the test set using metrics like AUC-ROC, precision, and recall [30].

- Prediction and Interpretation: Apply the best-performing model to predict targets for novel natural compounds. Validate top predictions experimentally or through molecular docking.

Deep Learning Advancements

Deep learning extends ML capabilities by automatically learning hierarchical feature representations from raw data, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel at processing structured grid data like molecular fingerprints and protein sequences, while more advanced architectures handle complex relational data [31]. A prime example is the DeepDGC model, which integrated a CNN and Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to explore licorice's mechanism against COVID-19, successfully predicting active compounds and targets that were later validated [31].

Key Application Protocol: Deep Learning-Based Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction

Objective: To predict the binding affinity between natural compounds and disease-associated targets using a deep learning model.

Materials:

- Computational Resources: GPU-accelerated computing environment (e.g., NVIDIA CUDA).

- Software Libraries: Deep learning frameworks such as PyTorch or TensorFlow.

- Datasets: KIBA database for pre-training; specialized natural product databases [31].

Procedure:

- Data Representation:

- Compounds: Encode as Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings, then convert to molecular graphs (for GCN) or Morgan fingerprints (for CNN) [31].

- Targets: Encode protein targets as amino acid sequences.

- Model Architecture:

- Implement a dual-input architecture. One branch processes the compound representation (using a GCN for graphs or CNN for fingerprints), while the other processes the protein sequence (using a CNN). The outputs are concatenated and passed through fully connected layers to predict a binding affinity score [31].

- Model Training:

- Pre-train the model on a large-scale DTI dataset like KIBA.

- Fine-tune the model on a specialized dataset of natural product interactions.

- Use mean squared error (MSE) as the loss function and the Concordance Index (CI) as a key evaluation metric [31].

- Validation:

- Perform experimental validation of top predictions using molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and in vitro assays.

Diagram 1: Deep Learning Framework for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction. This architecture integrates multiple data representations (molecular graphs and sequences) to predict compound-protein binding.

Graph Neural Networks in Action

GNNs represent the cutting edge for network pharmacology because they directly operate on graph-structured data, naturally modeling biological systems as interconnected networks [29]. Atoms in a molecule or proteins in an interaction network are treated as nodes, and their relationships (chemical bonds, interactions) as edges. This allows GNNs to inherently capture the topological information crucial for understanding polypharmacology. The application of GNNs has shown remarkable success in tasks including drug-target interaction prediction, drug repurposing, and molecular property prediction, significantly accelerating the early drug discovery pipeline [33] [29].

Key Application Protocol: GNN for Hub Target Identification

Objective: To identify critical hub targets within a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network related to a specific disease using a GCN-based model.

Materials:

- Software: Cytoscape for network visualization, PyTorch Geometric or Deep Graph Library for GNN implementation.

- Databases: STRING database for PPI data, GeneCards for disease-associated genes [32] [30].

Procedure:

- Network Construction:

- Graph Data Preparation:

- Represent the PPI network as a graph where nodes are proteins and edges are interactions.

- Assign node features, which could include gene expression data, network centrality measures, or encoded protein features.

- GNN Model Implementation:

- Implement a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) model. Each GCN layer aggregates information from a node's neighbors to refine its representation [32] [29].

- Train the model in a semi-supervised manner to predict the importance of each node (protein) in the network, using known key drivers from literature or initial CytoHubba results as labels.

- Validation:

- Validate the predictive performance of the model (e.g., R² values as high as 0.9858 on training data have been reported [32]).

- Perform experimental validation on top-predicted hub targets. For example, in a study on Alzheimer's disease, a GCNConv model validated 7 hub genes, including TNF, APP, and IL6, which were linked to neuroinflammatory pathways [32].

Table 2: Experimental Results from an AI-Driven Network Pharmacology Study on Vitis vinifera and Alzheimer's Disease [32]

| Analysis Stage | Key Output | Validation Metric / Result |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Screening | Identified 6 pharmacologically active compounds (e.g., flavylium, jasmonic acid). | Favorable pharmacokinetic properties predicted. |

| Hub Target Identification | Validated 7 hub genes (e.g., TNF, APP, IL6) via GCNConv model. | Model Performance (R²): Training: 0.9858, Validation: 0.9677, Testing: 0.9575. |

| Molecular Docking | Flavylium showed strong binding with 5 key targets (TNF, APP, IL6, PPARG, GSK3B). | Binding stability and affinity compared to control drug (Memantine). |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Network Pharmacology

| Resource Category | Name | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| TCM & Natural Product Databases | TCMSP [25], TCMID [25], HERB [28] | Provides comprehensive data on herbal compounds, targets, and associated diseases for network construction. |

| General Biological Databases | GeneCards [32] [31], STRING [32] [30], PubChem [32] [28] | Supplies disease-related genes, protein-protein interaction data, and small molecule information. |

| Pathway & Functional Analysis | KEGG [32] [28], DAVID [32] | Used for functional enrichment analysis of identified targets to elucidate biological pathways. |

| Network Analysis & Visualization | Cytoscape [32] [25] | Primary software platform for visualizing and analyzing complex "herb-compound-target-pathway" networks. |

| AI & Modeling Software | PyTorch/TensorFlow (with GNN libraries) [31] [29], SwissADME [31] | Frameworks for building DL/GNN models; tool for predicting absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion properties. |

Diagram 2: Workflow Evolution: From Traditional to AI-Enhanced Network Pharmacology. AI models integrate diverse data sources to generate prioritized predictions for experimental validation, increasing efficiency and success rates.

Network pharmacology represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving from the traditional "one target, one drug" model to a "network target, multi-component" approach that better captures the complexity of biological systems and multi-target therapies [34] [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for researching traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and other natural products, where therapeutic effects typically arise from complex interactions among multiple compounds working synergistically on multiple biological targets [35]. The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics has further accelerated the adoption of network pharmacology, enabling researchers to integrate and analyze massive amounts of biological, chemical, and clinical data [36]. Within this framework, specialized databases have become indispensable tools for managing the complex data relationships inherent in pharmacological research. STITCH, DrugBank, TCMSP, and STRING represent four essential databases that collectively cover the spectrum from chemical compounds and drug information to protein interactions and traditional medicine components, providing researchers with an integrated toolkit for systems-level pharmacological investigation [37] [38].

Table 1: Core Databases for Network Pharmacology Research

| Database | Primary Focus | Key Contents | URL | Applications in Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STITCH | Chemical-Protein Interactions | Known & predicted interactions between chemicals & proteins; 9.6M+ proteins from 2,031 organisms [36] | http://stitch.embl.de/ | Drug target identification, mechanism of action studies, side effect prediction |

| DrugBank | Drug & Drug Target Info | 14,746+ drugs with comprehensive drug-target associations, drug interactions, & metabolic pathways [36] | http://www.drugbank.ca | Drug screening, design, metabolism prediction, & pharmaceutical development |

| TCMSP | Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology | 500 herbs, 29,384 ingredients, 3,311 targets, 837 diseases with ADME properties [39] [35] | https://tcmsp-e.com/ | TCM mechanism studies, active compound screening, network analysis of herbal medicines |

| STRING | Protein-Protein Interaction Networks | 59.3 million proteins & >20 billion interactions across 12,535 organisms [40] | https://string-db.org/ | Pathway analysis, functional enrichment, network biology, & target validation |

Database Profiles and Capabilities

STITCH: Chemical-Protein Interaction Database

STITCH (Search Tool for Interacting Chemicals) is a comprehensive database focusing on known and predicted interactions between chemicals and proteins. The database integrates information from multiple sources including computational predictions, knowledge transfer between organisms, and interactions derived from other databases [36]. STITCH contains an impressive repository of approximately 9.6 million proteins from 2,031 different organisms, enabling researchers to explore chemical-protein interactions across a broad biological spectrum [36]. The database supports multiple query methods including chemical names, protein names, chemical structures, and protein sequences, making it highly accessible for various research scenarios. For large-scale analyses, STITCH provides both bulk download options and API access, facilitating integration with computational workflows and AI-driven drug discovery pipelines [36].

DrugBank: Pharmaceutical Knowledgebase

DrugBank stands as one of the world's most widely used drug information resources, containing detailed information on FDA-approved drugs, experimental therapeutics, and their molecular targets [41] [36]. The database serves as a critical bridge between drug discovery and clinical application by providing comprehensive data on drug-drug interactions, drug-target associations, drug classifications, and adverse reaction profiles [36]. With its extensive collection of over 14,000 drug entries, DrugBank has become an indispensable resource for drug screening, design, and metabolism prediction [36]. The database also offers specialized access through a Clinical API for healthcare software integration, making it valuable for both research and clinical applications [41]. The quantitative nature of the data in DrugBank, combined with its links to genomic and proteomic information, makes it particularly valuable for AI-based drug discovery and repurposing efforts.

TCMSP: Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database