Advanced Strategies for Yield Improvement in Natural Product Isolation: From Bench to Scalable Purification

This comprehensive article addresses the critical challenge of yield improvement in natural product isolation for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced Strategies for Yield Improvement in Natural Product Isolation: From Bench to Scalable Purification

Abstract

This comprehensive article addresses the critical challenge of yield improvement in natural product isolation for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it explores how modern approaches including targeted isolation guided by metabolomics, advanced chromatographic techniques with efficient scale-up protocols, biosynthetic yield enhancement, and systematic troubleshooting can significantly improve isolation efficiency and compound recovery. The content synthesizes current methodologies with practical optimization strategies to bridge the gap between analytical detection and preparative-scale isolation of bioactive natural products, ultimately accelerating natural product-based drug discovery pipelines.

Understanding Yield Challenges in Natural Product Isolation

The Critical Importance of Yield in Natural Product Research and Drug Development

Core Concepts: Yield in the Drug Development Pipeline

In both natural product research and synthetic drug development, yield is a pivotal factor that transcends mere quantitative output. It directly influences the viability, cost, and success of bringing a therapeutic from discovery to the clinic. For natural products, yield determines the feasibility of isolating sufficient material for bioactivity testing and structural elucidation. In the broader drug development context, the overall yield of viable drug candidates through the pipeline is critically low, with approximately 90% of clinical drug development failing despite entering human trials [1]. These failures are attributed to a lack of clinical efficacy (40–50%), unmanageable toxicity (30%), poor drug-like properties (10–15%), and other strategic factors [1].

The Yield Attrition Problem in Clinical Development

The following table summarizes the typical progression and high attrition rates of drug candidates through the development pipeline, illustrating the severe "yield" challenge.

Table 1: Drug Development Pipeline Attrition

| Development Stage | Typical Duration | Number of Candidates | Key Yield-Reduction Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery & Preclinical | 3-6 years [2] | 5,000 - 10,000 compounds [2] | Poor potency, selectivity, or drug-like properties (ADME) |

| Phase I Clinical Trials | Several months - 1 year [2] | ~100-200 compounds [2] | Unexpected human toxicity, undesirable pharmacokinetics |

| Phase II Clinical Trials | 1-2 years [2] | ~60-70% of Phase I entrants [2] | Inadequate efficacy in patients, safety issues |

| Phase III Clinical Trials | 2-4 years [2] | ~30-35% of Phase II entrants [2] | Insufficient efficacy in large trials, long-term safety risks |

| Regulatory Review & Approval | 0.5 - 1 year [2] | ~25-30% of Phase III entrants [2] | Incomplete evidence, manufacturing (CMC) issues |

| Market | - | 1 Approved Drug [2] | - |

Troubleshooting Guides for Yield Improvement

Guide 1: Low Yield in Natural Product Extraction

Problem: The amount of isolated bioactive compound from a natural source (plant, marine organism, microbe) is too low for further analysis or testing.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Natural Product Extraction Yield

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution & Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Extraction Technique | Review literature for similar compounds. Analyze the chemical nature (polarity, thermal stability) of your target compound. | - Shift from conventional (e.g., Soxhlet) to advanced techniques: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE), Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), or Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) [3]. - For heat-sensitive flavonoids/polyphenols, use UAE to prevent thermal degradation [3]. |

| Inefficient Cell Wall Disruption | Microscope inspection of plant material pre- and post-extraction. | - Employ hybrid strategies: Combine enzyme-assisted extraction (EAE) to break down cell walls with a mechanical method like UAE for synergistic yield increase [3]. |

| Incorrect Solvent System | Perform small-scale tests with solvents of varying polarity (e.g., hexane, chloroform, ethanol, water). | - Match solvent polarity to target compound: polar solvents (ethanol, water) for hydrophilic compounds (flavonoids, tannins); non-polar solvents (hexane) for lipophilic compounds (terpenoids, carotenoids) [3]. |

| Poor Raw Material Preparation | Check particle size distribution and moisture content. | - Reduce particle size to increase surface area for solvent penetration [3]. - Ensure proper drying to prevent dilution but avoid over-drying that can lead to degradation. |

Guide 2: Poor Translation from Preclinical Efficacy to Clinical Success

Problem: A compound shows high potency and efficacy in preclinical models but fails in clinical trials due to lack of efficacy or toxicity, representing a failure in the "yield" of successful candidates.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Preclinical-to-Clinical Translation

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution & Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Over-reliance on SAR over STR | Focus only on in vitro potency (IC50/Ki). | - Adopt a Structure–Tissue exposure/Selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) framework early in optimization [1]. - Prioritize Class I & III drugs: high tissue exposure/selectivity, even with adequate (not just high) potency [1]. |

| Inadequate Disease Biology Understanding | The target is validated in vitro but not critically in human disease biology. | - Use multiple, translationally relevant preclinical models. - Invest in humanized models or ex vivo human tissue assays to de-risk the target before major investment [4]. |

| Poor Drug-Like Properties | Unfavorable pharmacokinetics (PK) or pharmacodynamics (PD) in animal models. | - Rigorously optimize for drug-like properties (solubility, metabolic stability, bioavailability) using established criteria like the "Rule of 5" [1]. - Use in silico and in vitro ADME models for early screening. |

Guide 3: Low Yield in Biologically Active Compound Production

Problem: A validated natural product or complex drug (e.g., from marine symbionts) cannot be produced at sufficient scale or with consistent bioactivity for development.

Table 4: Troubleshooting Production of Bioactive Compounds

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution & Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Supply Bottleneck from Natural Harvesting | Source organism is rare, slow-growing, or ecologically protected. | - Identify the true producer (e.g., sponge vs. its symbiotic bacteria) [5]. - Develop sustainable production platforms: 1. Optimized cultivation of the producer microbe using novel techniques (floating filters, microcapsules) [5]. 2. Heterologous expression of the Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC) in a workhorse host like Streptomyces [5]. |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | Phytochemical or bioactivity profile varies significantly between batches. | - Standardize the process: Control plant species, geographic origin, harvesting time, and extraction parameters [3]. - Use advanced analytical techniques (HPLC, GC-MS, NMR) for rigorous chemical profiling and quality control of every batch [3]. |

| Formulation & Delivery Challenges | The compound has poor solubility, stability, or cannot reach its target tissue in vivo. | - For nucleic acid medicines/nanoparticles: Holistically optimize delivery vehicle composition, particle size, and surface properties [4]. - Explore advanced delivery systems (e.g., LNPs with targeting moieties) to move beyond passive liver accumulation [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most impactful change I can make to improve extraction yield for heat-sensitive natural products? A1: The most impactful change is to replace conventional Soxhlet extraction or maceration with Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE). UAE uses acoustic cavitation at lower temperatures to efficiently rupture cell walls and release intracellular compounds, significantly increasing yield while preserving the structural integrity and bioactivity of heat-labile molecules like flavonoids and polyphenols [3].

Q2: Our drug candidate is highly potent in vitro but showed low efficacy in a Phase II trial. What could we have done differently? A2: This common failure (~40-50% of clinical failures) often stems from an over-emphasis on in vitro potency (SAR) while overlooking tissue exposure and selectivity (STR). During optimization, candidates should be classified using the STAR framework. A "Class II" drug (high potency, low tissue selectivity) often requires a high dose, leading to toxicity without efficacy. Prioritizing "Class I/III" drugs (high tissue selectivity) ensures the drug reaches the disease site at effective concentrations with a lower, safer dose [1].

Q3: We've discovered a promising antifungal from a marine sponge, but supply is a problem. What are our options? A3: This is a classic supply challenge. First, work to identify the true producer, which is often a symbiotic bacterium rather than the sponge itself [5]. Then, pursue two main strategies:

- Advanced Cultivation: Use specialized techniques (e.g., microcapsule-based cultivation, in situ systems) to grow the previously "unculturable" symbiotic bacterium in the lab [5].

- Genetic Engineering: Isolate the Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC) responsible for producing the compound and express it heterologously in a tractable host like E. coli or Strengthened, enabling scalable fermentation for sustainable production [5].

Q4: Why do generic drugs, which contain the same API, face formulation challenges? A4: While the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is the same, generic formulations can use different inactive ingredients (excipients). Achieving bioequivalence—proving the generic drug releases its API into the bloodstream at the same rate and extent as the brand-name drug—is a major scientific hurdle. Minor differences in excipients, crystal form, or manufacturing process can significantly alter dissolution, stability, and absorption (ADME), requiring extensive "reverse-engineering" and formulation optimization to match the Reference Listed Drug's performance [6].

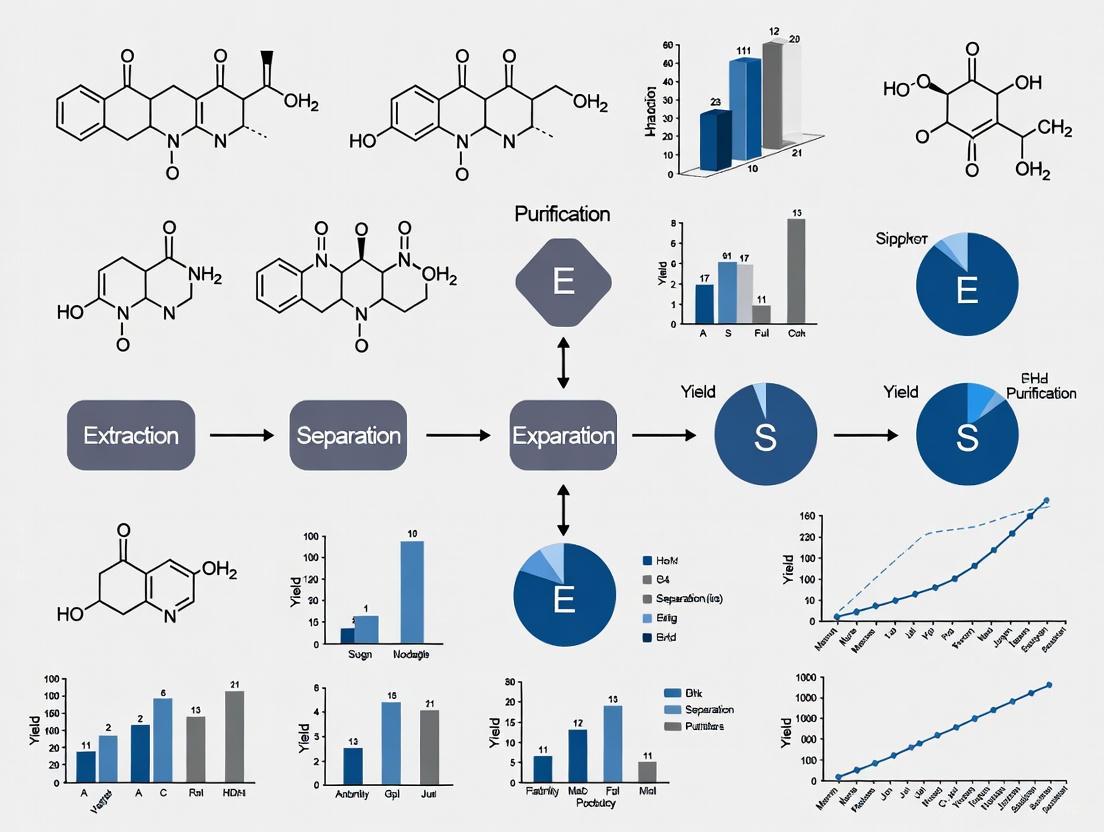

Visual Workflows for Yield Optimization

Diagram 1: Natural Product Isolation & Yield Optimization Workflow

Natural Product Isolation Workflow

Diagram 2: STAR Framework for Drug Candidate Selection

STAR Framework for Drug Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Reagents and Materials for Yield Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Adsorbents (e.g., XAD resins) | Concentration and purification of bioactive compounds from crude extracts during natural product isolation [5]. | Select resin type based on compound hydrophobicity; allows desorption with organic solvents. |

| Liquid Biofertilizer (PGPR) | Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria enhance nutrient uptake (N, P) and root growth in source plants, potentially increasing biomass and bioactive compound yield [7]. | Ensures sustainable cultivation of plant material for extraction. |

| Panchagavya | An indigenous organic formulation used as a foliar spray to enhance soil microbial activity, plant immunity, and nutrient assimilation in source plants [7]. | Can be combined with PGPR for synergistic effects on plant health and metabolite production. |

| Membrane-Permeable T6P Precursor | A novel biostimulant that acts as a molecular switch in plants to increase starch production and photosynthesis rates, significantly boosting crop yield (e.g., +10.4% in wheat) [8]. | Represents a cutting-edge tool to increase biomass of plant-based sources. |

| Enzyme Cocktails (e.g., Cellulase, Pectinase) | Used in Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) to selectively break down plant cell walls, facilitating the release of intracellular compounds and improving extraction yield [3]. | Particularly effective for compounds bound to the cell wall matrix; often used in hybrid strategies. |

| Genetically Tractable Hosts (e.g., S. coelicolor) | Used in heterologous expression of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) from unculturable symbiotic bacteria for sustainable production of marine natural products [5]. | Critical for solving the supply problem for promising marine-derived drug leads. |

| 1,3-Dichloro-1,1,2-trifluoropropane | 1,3-Dichloro-1,1,2-trifluoropropane|CAS 149329-27-1 | 1,3-Dichloro-1,1,2-trifluoropropane (CAS 149329-27-1) is a fluorinated intermediate for synthetic chemistry research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Isopteropodine | Isopteropodine, CAS:5171-37-9, MF:C21H24N2O4, MW:368.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In natural product isolation research, achieving high yield and purity is paramount for successful downstream analysis and drug development. The efficiency of this process is critically dependent on three fundamental factors: the nature of the source material, the structural complexity of the target compound, and its concentration within the source. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate specific challenges in optimizing these key factors, ultimately contributing to broader strategies for yield improvement.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Yield Due to Inefficient Compound Release from Source Material

- Question: Why is my extraction yield low even when using a high-quality source material?

- Background: The cellular and structural composition of the source material (e.g., plant, microbial biomass) can create significant barriers, preventing the efficient release of target compounds into the extraction solvent.

- Diagnosis: This issue often arises from rigid cell walls, waxy cuticles (in plants), or complex tissue matrices that the chosen extraction method cannot fully disrupt.

- Solution:

- Mechanical Pre-processing: Increase the surface area by grinding the source material to a finer powder under controlled temperatures (e.g., using cryo-milling with liquid nitrogen to prevent thermal degradation).

- Cell Disruption Enhancement: For microbial sources, employ high-pressure homogenization or ultrasonication. For plant tissues, consider enzymatic pre-treatment (e.g., with cellulase or pectinase) to break down structural polysaccharides.

- Solvent Selection and Soaking: Ensure the solvent polarity matches the target compound. Implement a soaking or swelling step, allowing the solvent to penetrate the tissue matrix before active extraction begins.

Problem 2: Co-isolation of Structurally Similar Compounds

- Question: How can I improve the separation of my target natural product from closely related analogs and impurities?

- Background: Structural complexity, especially within families of analogs (e.g., different ginsenosides or cannabinoids), leads to similar physicochemical properties, making separation challenging during chromatographic steps.

- Diagnosis: Poor resolution in analytical chromatography (e.g., TLC or HPLC) indicates that the current separation protocol cannot distinguish between the target and its analogs.

- Solution:

- Multi-dimensional Chromatography: Employ orthogonal separation methods. For instance, follow a size-exclusion step with a reversed-phase HPLC using a different mechanism of separation.

- pH Manipulation: For ionizable compounds, fine-tune the pH of the mobile phase to alter the charge state and selectivity of the separation. A small pH adjustment can significantly change retention times for acids and bases.

- Gradient Optimization: Instead of isocratic elution, use a carefully optimized gradient elution profile to achieve better resolution between closely eluting peaks.

- Question: What strategies can I use when the target compound is present in very low concentrations (e.g., <0.01% dry weight) in the source?

- Background: A low native concentration is a major bottleneck, requiring large amounts of starting material and highly efficient enrichment steps to obtain a usable quantity of the pure compound.

- Diagnosis: Initial analytical tests show a faint signal for the target compound, and scaling up the extraction does not yield sufficient material for characterization.

- Solution:

- Selective Enrichment: Use solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges with a functional group that selectively binds the target compound class (e.g., C18 for non-polar compounds, ion-exchange for charged molecules) to concentrate the analyte from a large volume of crude extract.

- Bio-guided Fractionation: Couple the isolation process to a robust biological activity assay (e.g., antimicrobial, enzymatic inhibition). This ensures that every purification step is tracked based on the enrichment of activity, efficiently guiding you toward the active, low-concentration compound.

- Scale-Up Considerations: Plan for a larger initial biomass batch. Pre-concentrate the crude extract using low-temperature evaporation or membrane filtration before proceeding to the first chromatographic step.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does the season or location of harvest impact the isolation of natural products from plant sources? The season, geographic location, and even time of day of harvest can dramatically alter the concentration and profile of secondary metabolites in a plant source [9]. These factors influence the plant's biochemical pathways in response to environmental stresses. It is crucial to standardize and document the harvesting conditions for reproducible isolation outcomes.

Q2: What is the single most important factor to consider when selecting a source material for isolation? While biological activity is key, the most important practical factor is often the concentration of the target compound within that source. A source with high specific content reduces the amount of biomass needed, simplifies the purification workflow, and improves overall isolation efficiency.

Q3: How can I quickly assess the complexity of a crude extract before starting a full isolation? Analytical techniques like Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) or Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) are excellent for initial assessment. TLC provides a visual snapshot of the number of constituents, while LC-MS reveals the complexity and can help identify the molecular weight of the target compound, informing your strategy for handling complex mixtures.

Q4: Why is my isolation yield inconsistent between batches even when using the same protocol? Inconsistency often stems from uncontrolled variation in the source material, such as different genetic cultivars, soil conditions, or post-harvest handling [9]. Implement strict quality control for your starting material, including botanical authentication and standardized drying/storage procedures.

Q5: Are there strategies to increase the concentration of a target compound within the source material itself? Yes, this is a powerful yield-improvement strategy. Techniques include:

- Elicitation: Treating plant cell cultures or whole plants with specific chemicals or stressors (e.g., jasmonic acid, UV light) to trigger the biosynthesis of desired secondary metabolites [10].

- Genetic Engineering: Modifying biosynthetic pathways in the host organism to overproduce the target compound.

- Optimized Cultivation: Applying specific water-nutrient-aeration-heat management frameworks, as seen in advanced agricultural tillage, can enhance the production of valuable compounds in plants [9].

Data Presentation

The following tables summarize key quantitative relationships that impact isolation efficiency.

Table 1: Impact of Source Material Pre-treatment on Extraction Yield

| Pre-treatment Method | Target Compound Class | Yield Improvement (%) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryogenic Grinding | Alkaloids, Terpenes | 15-30% | Preserves thermolabile compounds from degradation. |

| Enzymatic Maceration | Polyphenols, Glycosides | 20-50% | Enzyme specificity and incubation time are critical. |

| Ultrasonication | Essential Oils, Antioxidants | 25-60% | Can generate heat; requires temperature control. |

| Microwave-Assisted | Polar Molecules | 50-300% | Highly efficient but requires specialized equipment. |

Table 2: Guide to Separation Techniques Based on Compound Complexity

| Separation Technique | Principle | Best for Complexity Level | Resolution Capability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flash Chromatography | Polarity / Adsorption | Low to Medium | Moderate |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Polarity / Ion Exchange | Medium to High | High |

| Counter-Current Chromatography (CCC) | Liquid-Liquid Partition | High (closely related analogs) | Very High |

| Preparative Thin-Layer Chromatography (PTLC) | Polarity | Low (final purification) | Moderate |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Bio-guided Fractionation for Active Compound Isolation

This protocol is designed to efficiently isolate bioactive compounds from a complex extract, directly addressing challenges related to complexity and low concentration.

1. Preparation of Crude Extract:

- Function: To liberate the target compound from the source material and create a solution for initial testing.

- Methodology:

- Commence with dried, powdered source material (100 g - 1 kg).

- Perform exhaustive maceration or Soxhlet extraction with a solvent of graded polarity (e.g., hexane -> ethyl acetate -> methanol).

- Concentrate each extract in vacuo using a rotary evaporator at temperatures ≤40°C to prevent compound degradation.

- Determine the dry weight of each crude extract.

2. Primary Bioactivity Screening:

- Function: To identify the extract fraction with the desired biological activity.

- Methodology:

- Re-dissolve a small, precise amount of each crude extract in a suitable solvent for your bioassay (e.g., DMSO for in vitro assays).

- Subject these samples to a relevant biological activity test (e.g., antibacterial disk diffusion, enzyme inhibition assay).

- Identify the most active crude extract for further fractionation.

3. Fractionation and Tracking:

- Function: To simplify the complex mixture while tracking the active component.

- Methodology:

- Fractionate the active crude extract using vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC) or a similar open-column method.

- Collect fractions based on TLC profile or automated fraction collection.

- Concentrate all fractions and screen each one for bioactivity.

- Pool the active fractions for the next, higher-resolution separation step (e.g., HPLC).

4. Final Purification and Identification:

- Function: To obtain a pure compound from the active pool.

- Methodology:

- Use semi-preparative or preparative HPLC with an optimized mobile phase to isolate individual compounds from the active pool.

- Assess the purity of each isolated compound using analytical HPLC or LC-MS.

- Subject the pure, active compound to structural elucidation via NMR spectroscopy and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS).

Protocol 2: Optimized Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) for Pre-concentration

This protocol is crucial for handling samples where the target compound is in low concentration.

1. SPE Cartridge Selection and Conditioning:

- Function: To choose the appropriate sorbent chemistry for selective binding.

- Methodology:

- Select an SPE cartridge (e.g., C18 for non-polar compounds, SCX for basic compounds) based on the target's physicochemical properties.

- Condition the cartridge by passing 2-3 column volumes of a strong solvent (e.g., methanol) through it, followed by 2-3 volumes of the sample loading solvent (often water or a weak buffer). Do not let the sorbent dry out.

2. Sample Loading and Washing:

- Function: To bind the target and remove weakly retained impurities.

- Methodology:

- Load the sample, dissolved in a weak solvent, onto the conditioned cartridge. Use a slow flow rate (1-2 mL/min) to ensure efficient binding.

- Wash the cartridge with 2-3 volumes of a solvent that is strong enough to elute impurities but weak enough to leave the target compound bound.

3. Target Elution:

- Function: To release the concentrated target compound in a small volume.

- Methodology:

- Elute the target compound using a small volume (e.g., 2-5 mL) of a strong solvent (e.g., methanol with 1% formic acid).

- Collect the eluent and evaporate it to dryness. Re-dissolve the concentrate in a minimal volume of solvent for the next analytical or preparative step.

Visualization of Workflows

Diagram 1: Bio-guided Fractionation Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical sequence of steps in the bio-guided fractionation protocol, showing how activity tracking guides the isolation process.

Diagram 2: Source-to-Isolate Efficiency Pathway

This diagram illustrates the key factors and decision points that influence the overall efficiency of natural product isolation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions in natural product isolation workflows.

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for Isolation Research

| Item | Function in Isolation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges (C18, Silica, Ion-Exchange) | Selective pre-concentration and clean-up of target compounds from crude extracts. | Select sorbent chemistry based on the polarity and ionic character of the target compound. |

| Chromatography Stationary Phases (C18, Silica, Diol, Cyano) | High-resolution separation of complex mixtures in HPLC and flash chromatography. | Particle size and pore diameter affect resolution and flow resistance. |

| Solvents for Extraction & Chromatography (Methanol, Acetonitrile, Ethyl Acetate, Hexane) | Dissolving the source material and acting as the mobile phase to separate compounds. | Use HPLC-grade for analysis; technical grade for prep work. Prioritize safety and waste disposal. |

| Deuterated Solvents for NMR (CDCl3, DMSO-d6, MeOD) | Providing a medium for NMR analysis without interfering with the spectrum, enabling structural elucidation. | Handle in a fume hood; store properly as they are hygroscopic and expensive. |

| Bioassay Kits & Reagents | Tracking biological activity through the isolation process in bio-guided fractionation. | Ensure assay robustness and reproducibility for reliable results. |

| 7-Chloro-4-(piperazin-1-yl)quinoline | 7-Chloro-4-(piperazin-1-yl)quinoline | Research Chemical | |

| Imatinib-d8 | Imatinib-d8, CAS:1092942-82-9, MF:C29H31N7O, MW:501.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Historical vs. Modern Approaches to Yield Improvement

FAQs on Yield Improvement in Natural Product Isolation

FAQ 1: What is the most significant difference between historical and modern extraction methods? The most significant difference lies in efficiency and selectivity. Historical methods like maceration or decoction often require large volumes of solvent and extended extraction times (from hours to days), which can lead to the degradation of thermolabile compounds and result in lower yields [11] [12]. Modern techniques, such as Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) and Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), use elevated temperatures and pressures to complete extraction in minutes, significantly improving yield while reducing solvent consumption [13] [11] [12]. Furthermore, modern approaches allow for better preservation of sensitive bioactive compounds [14].

FAQ 2: My extraction yield is low. What are the first parameters I should optimize? You should systematically investigate these core parameters, which critically impact yield [11]:

- Solvent Selection: Choose a solvent with a polarity matching your target compound. Methanol is often highly efficient for a range of phytochemicals [13] [14].

- Temperature: Higher temperatures can increase solubility and diffusion but may degrade thermolabile compounds. An optimal temperature must be determined empirically [13] [11].

- Extraction Time: Ensure the process runs long enough to reach equilibrium, but avoid unnecessarily long times that can lead to decomposition [11].

FAQ 3: How can I prevent the degradation of bioactive compounds during extraction? To minimize degradation:

- Control Temperature: Use optimized, lower temperatures, especially for thermolabile pigments like chlorophylls [13].

- Minize Exposure Time: Employ modern methods like MAE or PLE that drastically reduce extraction time [12].

- Avoid Harsh Conditions: Be aware that high temperatures (e.g., 150°C in PLE) and prolonged static times can accelerate the breakdown of compounds like chlorophyll a into derivatives [13].

FAQ 4: What are "PAINS," and why should I be concerned about them during bioassay-guided isolation? PAINS (Pan Assay Interference Compounds) are chemical compounds that produce false-positive results in bioassays by interfering with the assay mechanics rather than through a specific biological interaction [15]. They are a major concern in natural products research because they can mislead isolation efforts, wasting significant time and resources on compounds that are not genuine drug leads. Proper dereplication and awareness of these promiscuous players are essential [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Extraction Yield

| Potential Cause | Recommended Action | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect solvent polarity | Survey solvents of varying polarity (e.g., hexane, acetone, methanol, water). Methanol often outperforms acetone for pigments [13]. | The "like dissolves like" principle. Solvent polarity must match the target compound for efficient dissolution [11]. |

| Particle size too large | Reduce the particle size of the raw plant material to a fine powder through grinding. | A smaller particle size increases the surface area, enhancing solvent penetration and solute diffusion out of the solid matrix [11]. |

| Inefficient method | Transition from maceration to a modern technique like MAE or UAE. | Modern methods disrupt cell walls more effectively through mechanisms like cavitation (UAE) or volumetric heating (MAE), leading to higher mass transfer [12] [14]. |

| Sub-optimal temperature | Systematically test a temperature gradient. For PLE of parsley pigments, 100°C was optimal over 150°C [13]. | Higher temperature increases solubility and diffusion, but there is a trade-off with compound stability [13] [11]. |

Problem: Degradation of Thermolabile Compounds

| Potential Cause | Recommended Action | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive temperature | Lower the extraction temperature. For fresh parsley, 100°C was better than 125°C or 150°C for chlorophyll integrity [13]. | Thermolabile compounds like chlorophylls and some alkaloids decompose at high temperatures [13] [16]. |

| Prolonged extraction time | Shorten the static extraction time. In PLE, a 5-minute time can be sufficient [13]. | Long exposure to heat and solvent, even at moderate temperatures, promotes chemical decomposition [11]. |

| Use of strong acids/bases | In acid-base extraction, use mild conditions and avoid prolonged exposure to extreme pH. | Harsh pH conditions can hydrolyze or otherwise degrade sensitive functional groups [17]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Batches

| Potential Cause | Recommended Action | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent raw material | Standardize the sourcing, drying, and grinding of plant material to ensure uniform particle size. | Biological variability and differing particle sizes lead to inconsistent solvent penetration and extraction efficiency [11]. |

| Variable solvent quality | Use high-purity, fresh solvents from the same supplier for comparable results. | Solvents can absorb moisture or degrade over time, altering their polarity and extraction efficiency. |

| Uncontrolled parameters | Strictly control and document temperature, extraction time, and solvent-to-solid ratio for every run. | These parameters directly govern the kinetics and equilibrium of the extraction process [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Yield Optimization

Protocol 1: Optimizing Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) for Leaf Pigments

This protocol is adapted from a study on extracting chlorophylls and carotenoids from fresh parsley, demonstrating how to balance yield and stability [13].

1. Objective: To systematically determine the optimal PLE conditions (solvent, temperature, static time) for the maximum recovery of chlorophylls and carotenoids from fresh plant leaves. 2. Materials and Equipment:

- Accelerated Solvent Extractor (e.g., Dionex ASE 350)

- HPLC system with Diode-Array Detection (DAD)

- Solvents: Methanol, Acetone (HPLC grade)

- Plant Material: Fresh parsley (Petroselinum crispum) leaves, frozen at -80°C.

- Stainless-steel extraction cells 3. Procedure:

- Sample Prep: Aliquot 1.0 g of frozen plant material into the extraction cell.

- Solvent Screening: Perform extractions at 100°C with a 5-minute static time, comparing methanol and acetone.

- Temperature Gradient: Using the superior solvent from step 1, run extractions at: Room Temperature, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 125, and 150°C.

- Static Time & Cycles: At the optimal temperature (e.g., 100°C), test static times of 1, 3, and 5 minutes, and cycle numbers of 1, 2, and 3.

- Analysis: Quantify Chlorophyll a, Chlorophyll b, β-carotene, and Lutein via HPLC-DAD. Monitor for degradation products (e.g., chlorophyll a derivative). 4. Key Findings from Reference Study:

- Solvent: Methanol consistently yielded higher amounts of both chlorophylls and carotenoids compared to acetone [13].

- Temperature: A balanced yield with low degradation was achieved at 100°C. Maximum carotenoid yield occurred at 125°C, but this accelerated chlorophyll a breakdown [13].

- Time/Cycles: Three 5-minute cycles at 100°C provided an excellent compromise between comprehensive extraction and compound stability [13].

Protocol 2: Comparing Extraction Methods for Phytochemicals

This protocol outlines a systematic comparison of conventional and modern methods for a general phytochemical analysis [14].

1. Objective: To evaluate the efficiency of different extraction techniques (CSE, UAE, MAE, UMAE) and solvents on the phytochemical yield and bioactivity of a plant extract. 2. Materials and Equipment:

- Plant Material: Lyophilized and powdered aerial parts.

- Solvents: Ethanol, Acetone, Water, DMSO.

- Equipment: Magnetic stirrer (CSE), Ultrasonic bath (UAE), Microwave extractor (MAE), Combined ultrasound-microwave instrument (UMAE).

- Rotary evaporator for concentration. 3. Procedure:

- Standardized Setup: For all methods, use a constant material-to-liquid ratio of 1:30 (g/mL) and a temperature of 25°C.

- Conventional Solvent Extraction (CSE): Stir the mixture magnetically in the dark for 1 hour.

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): Sonicate the mixture for 15 minutes at 250 W power.

- Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): Extract for 165 seconds at 550 W power.

- Ultrasound-Microwave-Assisted Extraction (UMAE): Extract for 165 seconds at 250 W (ultrasound) and 550 W (microwave) simultaneously.

- Post-Processing: Centrifuge all extracts, collect the supernatant, and concentrate using a rotary evaporator at 40°C.

- Analysis: Spectrophotometrically quantify total phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, and saponins. Assess antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. 4. Key Findings from Reference Study:

- The MAE method with ethanol as the solvent resulted in the highest concentrations of all measured phytochemical classes (phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, saponins) and the strongest biological activities [14].

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Extraction Method Efficiencies

| Extraction Method | Relative Yield (Example: Phytochemicals) | Typical Time Required | Solvent Consumption | Scalability | Suitability for Thermolabile Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration | Low [11] | Very High (2-7 days) [12] | High [11] | Good for large batches | Good (if room temp) [11] |

| Soxhlet | Moderate | High (4-24 hours) [12] | Moderate (recycled) | Good | Poor (continuous heating) [16] |

| Ultrasound (UAE) | Moderate-High [14] | Low (15-60 min) [14] | Moderate | Moderate | Good (can generate heat) |

| Microwave (MAE) | High [14] | Very Low (a few minutes) [14] | Low [12] | Moderate | Good (rapid, controlled heating) |

| Pressurized Liquid (PLE) | High [13] | Low (5-20 min) | Low [12] | Good (commercial systems) | Requires optimization [13] |

| Target Compound | Optimal Solvent | Optimal Temperature | Optimal Time/Cycles | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll a | Methanol | 100°C | Three 5-min cycles | Degrades significantly at 150°C |

| Chlorophyll b | Methanol | 100°C | Three 5-min cycles | More stable than Chl a at higher temps |

| β-Carotene & Lutein | Methanol | 125°C | Single 5-min cycle | Higher temp maximizes yield, but degrades Chl a |

| Balanced Pigment Profile | Methanol | 100°C | Three 5-min cycles | Best overall compromise for a stable, high yield |

Workflow and Strategy Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Extraction and Isolation

| Item | Function/Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol | A versatile, polar organic solvent highly effective for extracting a wide range of phytochemicals, including chlorophylls and carotenoids [13] [11]. | Outperformed acetone in the PLE of pigments from fresh parsley leaves [13]. |

| Acetone | A medium-polarity solvent commonly used for extracting pigments and less polar compounds. | A standard solvent for chlorophyll extraction, though it may be less efficient than methanol in some PLE applications [13]. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Salts in a liquid state used as green solvents; can dissolve both polar and non-polar natural products and are often used in combination with MAE or UAE [16]. | Potential application in the extraction of specific, hard-to-dissolve secondary metabolites, though their environmental impact requires further study [16]. |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ | A non-toxic, non-flammable solvent used in Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE), ideal for non-polar compounds like essential oils. Leaves no toxic residue [12] [16]. | The most common application is the decaffeination of coffee and extraction of hops for brewing [12]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | Used for rapid clean-up, fractionation, or concentration of crude extracts prior to further analysis. | Employed to remove undesirable contaminants or to trap pure isolates after HPLC separation for direct structure elucidation (e.g., via NMR) [16]. |

| C18 Chromatography | A reversed-phase stationary phase used in column chromatography (MPLC, HPLC) and SPE for separating compounds based on their hydrophobicity. | The workhorse for final purification steps, providing high-resolution separation of complex natural product mixtures [13] [16]. |

| Amythiamicin D | Amythiamicin D, CAS:156620-46-1, MF:C43H42N12O7S6, MW:1031.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Oleandomycin Phosphate | Oleandomycin Phosphate, CAS:7060-74-4, MF:C35H64NO16P, MW:785.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Biosynthesis is the process by which living organisms—including plants, marine organisms, fungi, and bacteria—produce complex natural products through specialized metabolic pathways [18] [19]. These natural products have long been a major source of bioactive compounds with critical applications across pharmaceutical, agricultural, and industrial sectors [18] [20]. For researchers aiming to isolate these valuable compounds, yield optimization presents a significant challenge, as natural production in native hosts is typically limited to minute quantities insufficient for commercial applications [18] [21] [20].

The fundamental challenge lies in the fact that natural products are synthesized in living systems through intricate, multi-step pathways where numerous factors can limit overall yield [21]. These bottlenecks can arise from problems in protein folding, co-factor availability, the absence of essential protein partners, metabolic crosstalk with other pathways, or insufficient expression of key biosynthetic enzymes [21]. Understanding how nature builds these complex molecules provides the essential foundation for developing strategies to overcome these limitations and achieve yields viable for research and commercial applications.

Fundamental FAQs: Understanding Biosynthetic Pathways

Q1: What are the basic components of a biosynthetic pathway?

Biosynthetic pathways consist of coordinated series of enzymatic reactions that convert simple starting materials into complex natural products. The core components include:

- Enzyme Systems: Large multi-functional proteins that assemble molecular skeletons, such as polyketide synthases (PKS) that build polyketides and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) that assemble peptides [18] [19].

- Tailoring Enzymes: Enzymes that modify the core skeleton through reactions including hydroxylation, methylation, glycosylation, and epoxidation [18] [22].

- Gene Clusters: Contiguous stretches of DNA in fungi and bacteria that contain most or all genes required for a particular natural product's biosynthesis [18] [21].

- Precursor Molecules: Basic building blocks such as amino acids, acyl-CoA derivatives, and other primary metabolites that provide the foundation for complex structures [19].

Q2: Why are native natural product yields typically low in wild-type organisms?

Natural producers typically yield limited quantities of desired compounds due to several evolutionary constraints:

- Ecological Function: Natural products are optimized for ecological roles (e.g., defense, signaling) rather than for high-yield production [22]. The amounts produced are sufficient for the organism's survival needs but rarely maximize potential output.

- Regulatory Controls: Native pathways contain complex feedback inhibition mechanisms that limit flux through biosynthetic pathways to prevent metabolic imbalance [21].

- Pathway Complexity: Many natural products are synthesized via branched pathways that produce mixtures of related compounds rather than a single product, dividing metabolic resources [18].

- Genetic Dispersion: In higher organisms, biosynthetic genes may not be clustered, leading to inefficient coordination of expression [21].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Yield Optimization Challenges

Symptoms: The desired natural product is detected but at concentrations too low for practical isolation.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Rate-limiting enzymes in the pathway cannot support high flux.

- Solution: Identify bottleneck steps through intermediate analysis and overexpress corresponding genes [21]. For the antibiotic mupirocin, researchers identified the gene controlling epoxidation (mmpE oxidase domain) and knocked it out to redirect flux toward a more stable analog (PA-C) with higher yield [18].

- Cause: Inadequate precursor supply.

- Solution: Engineer precursor pathways to increase building block availability. Enhance expression of genes involved in producing key precursors like malonyl-CoA for polyketides or amino acids for peptides [21].

- Cause: Poor expression of heterologous pathways in engineered hosts.

Experimental Protocol: Gene Knock-Out for Pathway Optimization

- Identify candidate tailoring enzyme genes through bioinformatic analysis of the biosynthetic gene cluster.

- Design homologous recombination vectors with antibiotic resistance markers flanking the target gene.

- Transform the producing strain and select for recombinants.

- Verify gene deletion via PCR and Southern blotting.

- Analyze metabolite profile of mutant strain compared to wild-type using HPLC-MS.

- Scale up fermentation of optimized strain and isolate the dominant product [18].

Problem 2: Unwanted Mixture of Structural Analogs

Symptoms: The production system yields multiple related compounds requiring difficult separation.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Promiscuous tailoring enzymes with broad substrate specificity.

- Solution: Use targeted gene knock-outs to eliminate specific tailoring reactions. In tenellin and bassianin biosynthesis, domain swapping between related gene clusters enabled production of single analogs in high yields [18].

- Cause: Incomplete regiocontrol in cyclization or assembly steps.

- Solution: Engineer key cyclization domains for improved specificity. In dimeric xanthone biosynthesis, gene knock-outs allowed isolation of the monomeric precursor and engineering of a strain producing only the major component [18].

Table: Yield Optimization Results from Biosynthetic Engineering

| Natural Product | Engineering Strategy | Outcome | Yield Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mupirocin (PA-C) | Knock-out of mmpE oxidase domain | Production of single, more stable analog | High-titre strain with PA-C as sole main product [18] |

| Dimeric Xanthones | Gene knock-outs to elucidate pathway | Strain producing only major component | Eliminated mixture problem [18] |

| 6-Deoxyerythronolide B | Combinatorial PKS module swapping | 61 different analogs generated | Library creation for structure-activity testing [22] |

| Epirubicin | Ketoreductase gene replacement | 4'-epi configuration sugar | Production of clinical agent [22] |

Problem 3: Heterologous Pathway Failure in Engineered Hosts

Symptoms: Biosynthetic genes express but produce little or no target compound.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incompatibility with host metabolism or cofactor availability.

- Solution: Supplement media with required cofactors or engineer host cofactor biosynthesis pathways [21].

- Cause: Improper folding or assembly of large enzyme complexes.

- Solution: Co-express chaperone proteins and ensure optimal fermentation conditions [21].

- Cause: Toxicity of intermediates to host organism.

- Solution: Identify and eliminate metabolic cross-talk by knocking out host enzymes that divert intermediates [21].

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Combinatorial Biosynthesis for Structural Diversity

Combinatorial biosynthesis applies genetic engineering to modify biosynthetic pathways to produce new and altered structures using nature's biosynthetic machinery [22]. This approach includes:

- Module Swapping: Exchanging domains between polyketide synthase modules to create novel backbone structures [22].

- Tailoring Enzyme Engineering: Introducing glycosylation, methylation, or oxidation enzymes from different pathways to create novel analogs [22].

- Pathway Hybridization: Combining genes from different biosynthetic pathways to generate hybrid natural products [22].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosynthesis Optimization

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Biosynthesis Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Knock-out Vectors | Targeted disruption of specific biosynthetic genes | Identifying rate-limiting steps; eliminating unwanted side reactions [18] |

| Heterologous Host Systems (E. coli, S. cerevisiae, A. oryzae) | Expression of pathways in genetically tractable backgrounds | Overcoming limitations of native producers; improving yields [18] [21] |

| COSurrogates (N-formyl saccharin) | Controlled CO release for carbonylation reactions | Enabling dearomatization cascades for complex scaffold formation [23] |

| Bioinformatic Tools (antiSMASH, SMURF) | Identification and analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters | Predicting enzyme functions; pathway elucidation [18] [19] |

| Hantzsch Ester | Biomimetic reduction agent | Diastereoselective reduction of indolenine moieties in pseudo-natural product synthesis [23] |

Biomimetic Synthesis and Pathway Inspiration

Bioinspired synthesis uses proposed biosynthetic pathways as blueprints for efficient laboratory synthesis [24]. This approach can:

- Guide Retrosynthetic Analysis: Proposed biosynthetic steps inform strategic bond disconnections [24].

- Enable Cascade Reactions: Biomimetic conditions can achieve rapid complexity generation in single operations, as demonstrated in the synthesis of chabranol using a Prins-triggered double cyclization [24].

- Validate Biosynthetic Hypotheses: Chemical synthesis under biomimetic conditions provides evidence for proposed biosynthetic pathways [24].

Workflow Visualization: Biosynthetic Pathway Optimization

Advanced FAQ: Computational and AI-Driven Approaches

Q3: How can computational tools help overcome yield limitations?

Modern bioinformatics and AI-driven approaches provide powerful strategies for yield optimization:

- Pathway Prediction Tools: Software like antiSMASH and SMURF identify biosynthetic gene clusters and predict their functions, enabling targeted genetic interventions [19].

- Machine Learning for Strain Optimization: AI algorithms can predict optimal genetic modifications and fermentation conditions by analyzing complex datasets, significantly reducing experimental trial and error [25].

- Molecular Representation Methods: Advanced cheminformatics translate molecular structures into computable formats, enabling virtual screening of potential pathway variants and analogs [26].

- Yield Prediction Algorithms: Computational frameworks can predict equilibrium assembly yields for complex structures, helping researchers identify optimal expression conditions before experimental implementation [27].

Q4: What emerging technologies show promise for biosynthesis yield improvement?

Several cutting-edge approaches are advancing yield optimization capabilities:

- Divergent Intermediate Strategies: Creating common synthetic intermediates that can be diversified into multiple natural product-like scaffolds, combining biological relevance with structural diversity [23].

- Deep Active Optimization: AI-powered pipelines that efficiently explore high-dimensional optimization spaces with limited data, ideal for complex biological systems [25].

- Automated Self-Driving Laboratories: Closed-loop systems that combine AI-directed experimentation with robotic automation for rapid optimization cycles [25].

- Pseudo-Natural Product Design: De novo combination of natural product fragments in arrangements not accessible through known biosynthetic pathways, creating novel compounds with retained biological relevance [23].

Optimizing yields in natural product biosynthesis requires a comprehensive understanding of both nature's synthetic machinery and modern genetic engineering tools. By systematically addressing bottlenecks through targeted genetic modifications, employing combinatorial biosynthesis for structural diversification, and leveraging increasingly sophisticated computational approaches, researchers can overcome the inherent limitations of natural production systems. The continued development of these strategies promises to enhance our access to valuable natural products and their analogs, supporting drug discovery and development efforts across multiple therapeutic areas.

Economic and Sustainability Considerations in Scalable Isolation

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Common Scalability Challenges

Q: My extraction yield is inconsistent when scaling up from bench to pilot scale. What could be the cause? A: Inconsistent yields during scale-up often stem from inefficient solute diffusion in larger volumes or suboptimal solvent-to-solid ratios. While smaller batches achieve equilibrium quickly, larger volumes require optimized parameters to ensure the solvent penetrates the solid matrix completely and the solute diffuses out effectively [11]. We recommend:

- Review Solvent-to-Solid Ratio: The greater the solvent-to-solid ratio, the higher the extraction yield; however, an excessively high ratio wastes solvent and extends concentration time. Re-optimize this ratio for your larger batch size [11].

- Increase Extraction Duration: The extraction efficiency increases with time until solute equilibrium is reached. You may need to extend the extraction duration for larger batches, but not beyond the point of equilibrium [11].

- Ensure Proper Particle Size: A finer particle size enhances solvent penetration and solute diffusion. Confirm that your raw material particle size is consistently small and has not changed between small and large batches [11].

Q: How can I reduce the high solvent consumption and cost in my large-scale isolation process? A: High solvent consumption is a major economic and environmental bottleneck. Transitioning from classical methods to modern techniques can significantly reduce solvent use.

- Consider Modern Extraction Technologies: Methods like Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) and Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) are designed to use less solvent. SFE, using supercritical COâ‚‚, is particularly noted for reducing ecological complications associated with organic solvents [16]. ASE performs extraction at elevated temperatures and pressures, enhancing efficiency and reducing the required solvent volume [11].

- Evaluate Real Costs: When calculating cost-effectiveness, consider indirect costs like technologist time, staff training, and expenses from increased turnaround time, not just reagent prices. A more efficient, albeit slightly more expensive, method may be more cost-effective overall [28].

Q: My isolated natural product purity is dropping at a larger scale. How can I improve it? A: Purity loss often occurs when isolation techniques that work well at small volumes are not directly translatable to larger ones.

- Implement Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF): For isolating nanometer-sized structures like extracellular vesicles (EVs), moving from centrifugal ultrafiltration to pump-driven TFF enables scalable processing of liters of culture while maintaining purity [29]. TFF can be incorporated into a workflow that also includes size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) for high-purity isolation [29] [30].

- Optimize Chromatography for Scale: Techniques like Medium-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (MPLC) and preparative High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) are widely used for the efficient fractionation and purification of substantial amounts of natural products at scale [16]. Ensure your chromatography system and columns are designed for preparative, not just analytical, workloads.

Q: What are the sustainability trade-offs between different extraction methods? A: The choice of extraction method has direct implications for environmental sustainability.

- Solvent Selection: The properties of the extraction solvent are crucial. Alcohols (EtOH and MeOH) are common but volatile. Ionic Liquids (ILs), used in assisted extraction, offer advantages like low vapor pressure and high thermal stability, but their biodegradability and environmental impact require further study [16].

- Energy Consumption: Methods like decoction and reflux extraction require sustained heat, increasing energy use. In contrast, ultrasound-assisted extraction, while efficient, generates heat that can damage thermolabile compounds, representing a different kind of resource waste [11] [16]. Selecting a method that aligns with your compound's stability and your facility's energy profile is key.

Quantitative Data for Process Selection

The table below summarizes key economic and operational characteristics of common isolation techniques to aid in process selection and yield improvement strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Scalable Isolation and Extraction Techniques

| Technique | Typical Scale | Solvent Consumption | Processing Time | Key Sustainability Considerations | Primary Application in Natural Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration [11] | Bench to Pilot | High | Long (hours to days) | High solvent waste, low energy use | Simple, low-cost extraction; thermolabile compounds. |

| Percolation [11] | Bench to Pilot | High | Medium to Long | High solvent waste, low energy use | Continuous extraction, more efficient than maceration. |

| Soxhlet Extraction [11] [16] | Bench | Medium | Long | Recycles solvent but energy-intensive | Efficient for solid samples, but uses heat. |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) [11] [16] | Bench to Pilot | Low to Medium | Short | Reduced solvent use, but generates heat | Rapid extraction via cavitation; good for thermolabile compounds. |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) [11] [16] | Bench to Pilot | Low | Very Short | Reduced solvent and energy use | Very efficient and fast heating; multiple methodology variants exist. |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) [11] [16] | Pilot to Industrial | Very Low | Short | Uses COâ‚‚ (non-toxic); low solvent waste | Green technology for non-polar to medium-polar compounds. |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) [29] | Pilot to Industrial | Low (for buffers) | Medium | Enables concentration without solvent; scalable | Isolating vesicles, nanoparticles, and biologics from large volumes. |

Experimental Protocol: Scalable Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles

This protocol exemplifies a scalable and reproducible isolation workflow, balancing yield with purity, adaptable for natural product isolation research.

Methodology for Scalable EV Isolation using TFF and SEC [29]

1. Clarifying Bacterial Culture Medium by Centrifugation and Filtration

- Centrifugation: Transfer bacterial cell culture to centrifuge bottles. Centrifuge at 4°C and 5,000 × g for 15 min. Pour the supernatant into clean bottles and centrifuge again at 10,000 × g for 15 min. Repeat if large cell pellets persist.

- Filtration: Transfer the supernatant through a 0.22 μm polyethersulfone vacuum-driven filter unit. This step removes remaining cells and debris. Check for complete removal of viable cells by plating an aliquot on agar plates.

2. Concentration of the Filtered Medium using Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF)

- Setup: Assemble a TFF circuit with a 100 kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) device, using #16 low-binding tubing and a peristaltic pump. Perform this step in a biosafety cabinet to prevent contamination.

- Process: Circulate the filtered medium at approximately 200 mL/min. The goal is to retain EVs while allowing molecules <100 kDa to pass through as waste.

- Diafiltration: Continue circulating until the volume is reduced to ~100-200 mL. Dilute the concentrate 2-fold with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and continue concentrating. Repeat this diafiltration step to further purify and exchange the buffer.

- Final Concentration: Concentrate the sample down to a final volume of <10 mL. Recover the sample by purging the filter. For the final concentration step, the sample can be transferred to a 15 mL 100 kDa MWCO centrifugal ultrafiltration device and spun at 2,000 × g until the volume is <2 mL.

3. Purification by Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

- Principle: The concentrated sample is applied to an SEC column optimized for EV purification. Larger EVs elute in the early fractions, separated from smaller soluble proteins and contaminants that elute later.

- Validation: The presence of EV-associated markers can be confirmed using techniques like immunogold labeling and transmission electron microscopy [29].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in the scalable EV isolation protocol.

Scalable EV Isolation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Large-Scale Cell and Natural Product Workflows

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Leukopaks [28] | Large-volume peripheral blood source providing high leukocyte counts. | Sourcing large quantities of human primary immune cells for immunology research, vaccine development, and cell therapy. |

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) [28] | Cryopreserved mononuclear cells isolated from peripheral blood. | Ready-to-use, well-characterized human immune cells for high-content screening, disease modeling, and assay development. |

| Immunomagnetic Cell Separation Kits [28] | Antibody-coated magnetic particles for positive or negative selection of specific cell types. | Rapid, high-purity isolation of target cells (e.g., CD34+ cells) from large-volume samples like leukopaks or whole blood. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns [29] [30] | Chromatographic columns that separate particles based on hydrodynamic radius. | High-resolution purification of EVs, lipoproteins, or other nanoparticles from soluble proteins and contaminants. |

| Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) Systems [29] | Filtration systems where flow is parallel to the filter surface, minimizing clogging. | Gentle concentration and buffer exchange of valuable biomolecules from liters of culture medium or other large-volume samples. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) [16] | Organic salts in liquid state with low vapor pressure, used as extraction solvents. | Potential "greener" solvents for the extraction of a wide range of polar and non-polar natural products. |

| Millewanin G | Millewanin G, CAS:874303-33-0, MF:C25H26O7, MW:438.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 6-Amino-5-azacytidine | 6-Amino-5-azacytidine, CAS:105331-00-8, MF:C8H13N5O5, MW:259.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Techniques for Enhanced Recovery and Purity

In natural product research, the process of isolating novel compounds is often hampered by the rediscovery of known molecules, leading to significant resource and time expenditure. Metabolite profiling and dereplication are therefore critical for efficiently identifying known compounds early in the discovery pipeline. When framed within strategies for yield improvement, these processes ensure that effort is concentrated on the most promising, novel leads. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate the common challenges in this field.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between metabolite profiling, metabolite fingerprinting, and dereplication?

- Metabolite Profiling focuses on the analysis of a large group of metabolites, either related to a specific metabolic pathway or a class of compounds. It is generally more targeted than fingerprinting and is considered the precursor to metabolomics [31].

- Metabolite Fingerprinting is a high-throughput, untargeted approach used for the rapid classification and comparison of samples. The goal is not to identify every metabolite, but to compare patterns or "fingerprints" that change in a biological system, often as a hypothesis-generating activity [31].

- Dereplication is the process of quickly identifying known compounds in a biologically active crude extract early in the discovery process. This prevents the redundant isolation and characterization of previously described substances, thereby saving resources and accelerating the discovery of novel entities [31] [32] [33].

Q2: What are the major bottlenecks in natural product discovery that these strategies aim to address? Two major bottlenecks hinder efficient natural product discovery [33]:

- Dereplication: The early and accurate identification of known compounds to avoid rediscovery.

- Structure Elucidation: Particularly, the determination of the relative and absolute configuration of metabolites with stereogenic centers. Advanced analytical and computational methods are being developed to alleviate these obstacles.

Q3: Which analytical platforms are most commonly used, and why is a multi-platform approach often necessary? No single analytical technique can comprehensively cover the vast chemical diversity of a metabolome. The combination of multiple, orthogonal technologies is necessary for extensive metabolome coverage [31]. Key platforms and their roles are summarized below.

| Analytical Platform | Key Strengths | Common Applications in Profiling/Dereplication |

|---|---|---|

| LC–HRMS (Liquid Chromatography–High Resolution Mass Spectrometry) | High sensitivity and resolution; provides accurate mass data [31] [34] | Primary tool for dereplication; metabolite profiling and annotation via database searches [31]. |

| NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) | Non-destructive; provides detailed structural and stereochemical information [31]. | Structural elucidation and confirmation; fingerprinting via 1D or 2D experiments [31] [33]. |

| GC–MS (Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry) | Highly reproducible; excellent for volatile compounds [31]. | Targeted profiling of primary metabolites (e.g., sugars, amino acids) [31]. |

| Molecular Networking (e.g., GNPS) | Organizes MS/MS data based on spectral similarity; visualizes compound families [34] [35]. | Dereplication and discovery of structural analogues within a sample; identifies both known and unknown compounds [35]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inefficient Dereplication Leading to Rediscovery of Known Compounds

Issue: Despite running LC-MS, researchers frequently re-isolate and identify compounds that are already known, wasting valuable time and resources.

Solutions:

- Implement Tandem MS and Molecular Networking: Do not rely solely on LC-MS (MS1) data. Use data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or data-independent acquisition (DIA) to generate MS/MS fragmentation data. Process this data through the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform to visualize clusters of related compounds and efficiently dereplicate known molecules based on spectral libraries [34] [35].

- Combine Orthogonal Data: Integrate HRMS data with NMR analysis for more confident identification. While MS is highly sensitive for dereplication, NMR provides unparalleled structural information that can confirm identity and stereochemistry, which is often challenging for MS alone [31] [33].

- Utilize Advanced Databases and Bioinformatics: Leverage open-access and commercial natural product databases (e.g., AntiMarin, MarinLit) and chemoinformatic tools. Machine learning and in-silico fragmentation prediction are becoming increasingly powerful for annotating compounds that are not in existing libraries [32] [33].

Experimental Protocol: Integrated LC-MS/MS and Molecular Networking for Dereplication [35]

- Sample Preparation: Extract plant material (e.g., 50 mg) with a solvent mixture like methanol/water/formic acid (49:49:2; v/v/v) via sonication. Centrifuge, combine supernatants, and reconstitute for LC-MS analysis.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Column: C18 column (e.g., 2.1 × 150 mm, 1.8 μm).

- Mobile Phase: (A) 8.0 mmol/L ammonium acetate in water; (B) acetonitrile.

- Gradient: Use a multi-step elution (e.g., 5% B to 98% B over 20 minutes).

- Mass Spectrometry: Acquire data in both DDA and DIA (e.g., SWATH) modes on a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF).

- Data Processing:

- Convert raw data files to an open format (e.g., .mzML) using MSConvert.

- For DIA data, use software like MS-DIAL to deconvolute and extract pseudo-MS/MS spectra.

- For DDA data, process with MZmine for feature detection and alignment.

- Molecular Networking and Annotation:

- Upload the processed MS/MS spectral files to the GNPS website.

- Use the GNPS workflow to create a molecular network and annotate nodes by matching against spectral libraries.

- Combine results from DDA and DIA approaches for comprehensive coverage.

Problem 2: Difficulty in Correlating Metabolic Features with Observed Bioactivity

Issue: A crude extract shows promising bioactivity, but the complexity of the mixture makes it impossible to pinpoint which metabolite(s) are responsible.

Solutions:

- Apply Metabolomics and Chemometrics: Use a mass spectrometry-based metabolomics approach to statistically compare the chemical profiles of active versus inactive fractions or extracts. Multivariate data analysis (MVDA) tools like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares (sPLS) can highlight the metabolic features that are most discriminatory between the groups, pointing to potential active compounds [34].

- Incorporate Bioactivity Data Early: Use techniques like HPLC-based activity profiling, where fractions are collected after chromatographic separation and are directly subjected to bioassays. This directly links a region of the chromatogram to the biological effect [31].

Experimental Protocol: Metabolomics Workflow for Bioactive Compound Discovery [34]

- Sample Preparation & Fractionation: Prepare multiple extracts and fractions from your source material (e.g., different plant parts, various solvent partitions) to create a set of samples with varying chemical profiles and bioactivities.

- Bioassay: Test all samples for the desired biological activity (e.g., larvicidal activity) at a standardized concentration.

- LC-MS Data Acquisition: Analyze all samples using UHPLC-HRMS in full-scan mode to obtain MS1 data.

- Data Pre-processing and Statistical Analysis:

- Use software like MZmine to perform peak detection, alignment, and to create a data matrix (features = m/z and RT, samples, peak areas).

- Import the data matrix into a platform like MetaboAnalyst.

- Perform unsupervised (PCA, HCA) and supervised (sPLS) analyses to identify features (m/z ions) that are significantly more abundant in active samples.

- Annotation of Active Features: Putatively annotate the discriminatory features by querying their accurate mass against natural product databases or by integrating with MS/MS data from a separate run.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Metabolite Profiling & Dereplication |

|---|---|

| Diol Cartridges | Used for solid-phase extraction (SPE) to fractionate crude extracts into cleaner sub-fractions (e.g., hexane, ethyl acetate, methanol elutions), reducing complexity for downstream analysis [34]. |

| C18 U/HPLC Columns | The workhorse stationary phase for reverse-phase chromatographic separation of a wide range of natural products, providing high resolution for complex mixtures [31] [35]. |

| Ammonium Acetate / Formic Acid | Common volatile additives to the LC mobile phase. They assist in ionization during MS analysis (by controlling pH) without causing instrument contamination [35]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O, CD₃OD) | Essential for NMR spectroscopy, allowing for solvent locking and shimming without introducing extraneous signals in the spectrum [36]. |

| Imazalil sulfate | Imazalil sulfate, CAS:58594-72-2, MF:C14H16Cl2N2O5S, MW:395.3 g/mol |

| Cyazofamid | Cyazofamid, CAS:120116-88-3, MF:C13H13ClN4O2S, MW:324.79 g/mol |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a streamlined, integrated strategy for metabolite profiling and targeted isolation that maximizes resource efficiency.

Integrated Workflow for Efficient Natural Product Discovery

Metabolomics Data Analysis for Bioactivity Correlation

The efficient transfer of analytical methods to semi-preparative scale represents a critical pathway for enhancing yield in natural product isolation research. This process integrates powerful metabolite profiling with targeted purification, enabling researchers to isolate high-purity natural products from complex biological matrices more efficiently [36]. The fundamental principle involves scaling separation conditions that have been optimized at the analytical level using UHPLC to the semi-preparative level through chromatographic calculation, ensuring similar selectivity at both scales [36]. This strategic approach minimizes re-optimization efforts, reduces solvent consumption, and accelerates the isolation of bioactive compounds for drug development pipelines.

Core Concepts and Scaling Principles

Defining Chromatographic Scales

The distinction between analytical, semi-preparative, and preparative chromatography is defined not just by column dimensions but by the objective of the separation. Preparative Liquid Chromatography (LC) encompasses any workflow where the goal is to isolate specific fractions from a sample for purification, regardless of column size [37]. The scale chosen for a purification workflow depends primarily on two factors: the required yield (amount of purified compound needed) and the challenge of the purification (the resolution required to separate target compounds from impurities) [37].

- Analytical Scale: Primarily used for quantification and identification. Typical column dimensions are 2.1-4.6 mm internal diameter (i.d.) with flow rates below 2 mL/min [38].

- Semi-Preparative Scale: Employed for small-scale purification to obtain pure compounds for structural characterization or bioactivity testing. Columns typically range from 10-30 mm i.d. with flow rates between 5-50 mL/min [38].

- Preparative Scale: Used for large-scale purification, often for manufacturing purposes. Columns usually range from 50-200 mm i.d. and are run at flow rates >50 mL/min [38].

Fundamental Scaling Calculations

The transition from UHPLC to semi-preparative scale can be predictably managed using straightforward calculations based on column geometry. The key parameters are the Loading Capacity Ratio (LCR) and the flow rate, which scale with the cross-sectional area of the column [39].

For a standard 0.46 cm i.d. x 25 cm length analytical column taken as the reference (LCR = 1), the relative loading capacities and flow rates for larger columns are as follows:

Table: Scaling Factors for Column Sizes Based on a 0.46 x 25 cm Analytical Column

| Column Size (i.d. x Length) | Loading Capacity (LCR) | Flow Rate (mL/min) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.46 x 25 cm | 1 | 1.0 |

| 1 x 25 cm | 5 | 5.0 |

| 2 x 25 cm | 19 | 19 |

| 5 x 50 cm | 250 | 50 |

| 10 x 50 cm | 1000 | 200 |

The preparative load (W_PREP) is calculated using the maximum experimental load on the analytical column (W_E) and the LCR from the table [39]:

WPREP = WE × LCR

Determining the Maximum Analytical Load (W_E): To find W_E, first develop a separation method on an analytical column that provides baseline resolution. Then, prepare a concentrated solution of the target compound in the mobile phase and progressively increase the injection volume until the valley between the target peak and the nearest impurity begins to rise. W_E is calculated as [39]:

WE = Cmax × VA_max

where C_max is the maximum sample concentration and VA_max is this maximum injection volume before overloading.

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for transferring a method from analytical UHPLC to semi-preparative scale.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Scaling Issues and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Common Method Transfer Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Resolution after scale-up | Gradient not properly scaled; volume overload; excessive sample mass. | Ensure linear velocity is maintained; re-calculate and adjust gradient time based on column geometry; reduce sample load; consider dry-load introduction for better peak shape [36]. |

| Peak Tailing or broadening | Inadequate column efficiency at semi-prep scale; chemical contamination of stationary phase. | Use columns packed with smaller particles (e.g., 3-5 µm) for higher resolution; implement stringent sample cleanup/pre-filtration; replace worn-out or contaminated column [36] [40]. |

| Pressure Fluctuations or high backpressure | Blocked column frits; incompatible solvent mixture; system blockage. | Inspect and replace column frits and fittings; ensure mobile phase compatibility; flush system thoroughly; perform regular instrument maintenance [40]. |

| Irreproducible Retention Times | Improper system equilibration; mobile phase proportioning errors; pump malfunctions. | Allow for sufficient column equilibration time; check pump seal integrity and check valve function; prepare mobile phases consistently [40]. |

| Low Recovery of target compound | Sample adsorption; compound degradation during evaporation; ineffective fraction collection triggering. | Use alternative stationary phase chemistries (e.g., HILIC, ion-pairing); optimize fraction collector settings and delay volume; use milder evaporation conditions (e.g., low heat, nitrogen blow-down) [36] [37]. |

Systematic Troubleshooting Flowchart

For a logical, step-by-step approach to diagnosing issues, follow this flowchart.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical parameter to maintain when scaling from UHPLC to semi-preparative HPLC? The most critical parameter is selectivity, which is achieved by maintaining the same stationary phase chemistry and ensuring the scaled mobile phase composition closely matches the original analytical conditions. This ensures that the relative separation between compounds is preserved during scale-up [36].

Q2: How much sample can I load onto my semi-preparative column?